#angli-Scottish

Text

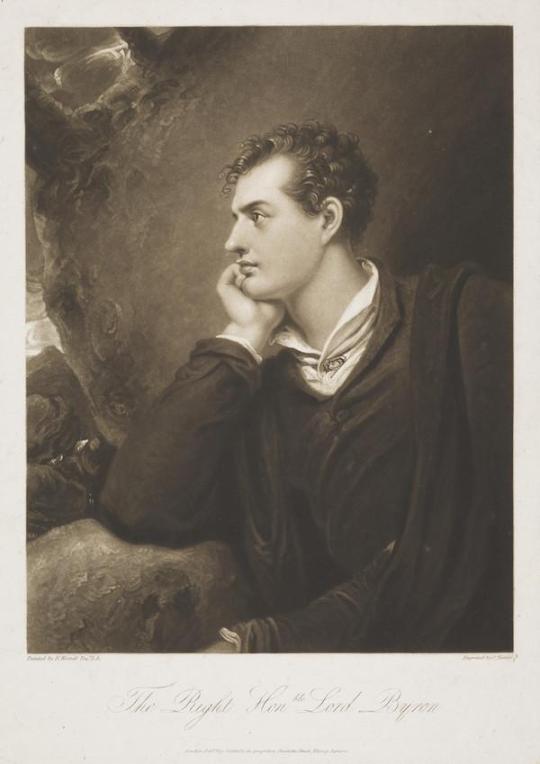

January 22nd 1788 the poet George Gordon Byron, better known as Lord Byron was born in Holles Street, London

Lord Byron’s mother was Scottish, and for his first ten years they lived in Aberdeen, where he attended the Grammar, until he succeeded to his title. He always considered himself a Scot. He wrote in Don Juan: ‘But I am half a Scot by birth, and bred /A whole one, and my heart flies to my head…’

The most glamorous member of the second generation of Romantic poets, he was a prolific writer, led a scandalous life, and died in the Greek war of independence, aged 34. . Apart from his short lyrics, his poetry is perhaps less read now than his extraordinarily vivid letters and journals; his life continues to intrigue readers, scholars and film-makers.

Of course the Scots remember him for the brilliant poem Lochnagar, a favourite of my friend Roland, adapted into a folk song by The Corries, but I am going to post another of his “Scottish” poems called When I Roved A Young Highlander.

When I roved a young Highlander o'er the dark heath,

And climb’d thy steep sumrnit, oh Morven of snow!

To gaze on the torrent that thunder’d beneath,

Or the mist of the tempest that gather’d below,

Untutor’d by science, a stranger to fear,

And rude as the rocks where my infancy grew,

No feeling, save one, to my bosom was dear

Need I say, my sweet Mary, 'twas centred in you?

Yet it could not be love, for I knew not the name,-

What passion can dwell in the heart of a child?

But still I pereceive an emotion the same

As I felt, when a boy, on the crag cover’d wild:

One image alone on my bosom impress’d

I loved my bleak regions, nor panted for new;

And few were my wants, for my wishes were bless’d;

And pure were my thoughts, for my soul was with you.

I arose with the dawn; with my dog as my guide,

From mountain to mountain I bounded along

I breasted the billows of Dee’s rushing tide,

And heard at a distance the Highlander’s song:

At eve, on my heath-cover’d couch of repose,

No dreams, save of Mary, were spread to my view;

And warm to the skies my devotions aoose,

For the first of my prayers was a blessing on you.

I left my bleak home, and my visions are gone;

The mountains are vanish’d, my youth is no more;

As the last of my race, I must wither alone,

And delight but in days I have witness’d before:

Ah! splendour has raised but embitter’d my lot;

More dear were the scenes which my infancy knew:

Though my hopes may have fail’d, yet they are not forgot;

Though cold is my heart, still it lingers with you.

When I see some dark hill point its crest to the sky,

I think of the rocks that o'ershadow Colbleen

When I see the soft blue of a love-speaking eye

I think of those eyes that endear’d the rude scene;

When, haply, some light-waving locks I behold,

That faintly resemble my Mary’s in hue,

I think on the long, flowing ringlets of gold,

The locks that were sacred to beauty, and you.

Yet the day may arrive when the mountains once more

Shall rise to my sight In their mantles of snow:

But while these soar above me, unchanged as before

Will Mary be there to receive me? - ah, no!

Adieu, then, ye hills, where my childhood was bred!

Thou sweet flowing Dee, to thy waters adieu!

No home in the forest shall shelter my head,–

Ah! Mary, what home could be mine but with you?

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

What do Shax and a 30-year-old Sandman comic have in common? Puns. The answer is always puns.

While I've recently revealed Shax does actually know how to spell, (she's just really old), the "angle" message Shax throws through the window to demand the "angel" one was a little trickier, because it's not Middle English, or even Old French, it's probably the oldest pun in Good Omens... it's latin.

Good Omens Season 2, Episode 5, 2023

Fortunately, a time travelling Neil Gaiman left answers for us in his 1995 Sandman special "Sandman midnight theatre." See for yourself.

Sandman Midnight Theatre, Neil Gaiman, Matt Wagner, Teddy Kristiansen, 1995

"Still, they have some illuminated manuscripts in their library which throw fascinating light on early church history. "Not angels, but angles" eh? I've been angling for permission to browse through their manuscript collection for yonks."

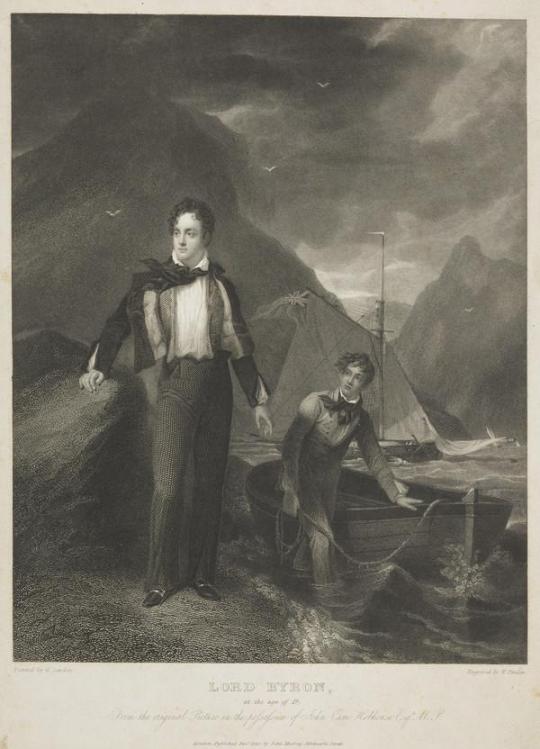

Appropriate for an English reverend to be curious about "Angels and not Angles". It's THE earliest christian pun, attributed to Pope Gregory the Great in the 6th century CE.

Oxford reference essential quotations

It comes from a historical account of the pope walking through a market in Rome, and seeing some exotic slave children (i.e. fair hair and blue eyes, and light skin) from what is now the England, and asking where they were from. The master replied that they were "Angles" (Angli in latin) and the pope declared them to be "Angels" (Angeli) instead, which, in latin at that time would have been a pun.

This history from Bede actually influenced a lot of the christian world, so we could conceivably make the point that fair blonde and blue eyed angels comes from the idea that they looked liked the English (who were not christian, but pagan at the time of being newly conquered). Aziraphale's looks in the originsl Good Omens are probably a direct result of the lineage in art of this 1,500 year old pun.

Depictions of angels, 1100 years apart

Which raises the question: if Shax is asking for the Angel Gabriel with her note, the pun doesn't make any fucking sense.

Jon Hamm plays Gabriel as an "American", specifically not English like the rest of the cast. He does have blue eyes, but as far as Shax is concerned, Gabriel's eyes are violet, not really a human colour. Shax could just actually be stupid (I guess?) and not realize that in modern English that constitutes a mistake (boring), or that Americans succeeded in 1776 (hilarious). But here's a quirkier theory: Shax knows what she's talking about, and she's gunning for Maggie.

If you look really closely, demons show up and start hanging around the street earlier in the ball than you would guess. Once a fair number have amassed, they stay waiting for Shax to lead them. However, even though she hasn't shown up yet, they eagerly chase Maggie down the street from her shop. They're only stopped by Crowley, and Maggie gets safely into the ball.

Once inside, she has quite a stunning change of costume, highlighting her blonde hair and blue eyes:

There's so much more evidence to suggest that Maggie isn't really a normal human, but this post is long enough. What I will say is that it's subtle, but once the demon attack really gets going (no thanks to Maggie), Shax and the other demons never look for Jim once, even when he leaves the mezzanine. They concentrate all their efforts on Aziraphale, Maggie and Nina, and never mention Gabriel again.

While Maggie is a Scottish name, and she clearly has some links to Scotland if a random pub in Edinburgh is buying records from her in Soho, she does have a distinctly English accent, and lest we forget...

———————————————

thanks as always to @embracing-the-ineffable and @thebluestgreen for the tasty links and sounding board.

#good omens meta#good omens 2#art director talks good omens#go season 2#go meta#good omens season two#good omens season 2#good omens#go2#good omens prime#nina and maggie#anthony j crowley#jimbriel#crowley x aziraphale

84 notes

·

View notes

Text

Today the Church remembers Saint William of Perth (died c. 1201 AD), also known as Saint William of Rochester.

Ora pro nobis,

William was a Scottish saint, born in Perth, Scotland, in the 12th c. AD, who was martyred in England while on pilgrimage. He is the patron saint of adopted children.

Life

Practically most that is known of William comes from the Nova Legenda Anglie, and that is little. He was born in Perth, at that time one of the principal towns of Scotland. In youth, he had been somewhat wild, but on reaching manhood he devoted himself wholly to the service of God. A baker by trade (some sources say he was a fisherman), he was accustomed to setting aside every tenth loaf for the poor.

He went to Mass daily, and one morning, before it was light, found on the threshold of the church an abandoned child, whom he adopted and to whom he taught his trade. Later he took a vow to visit the Holy Places, and, having received the consecrated wallet and staff as a Palmer, set out with his adopted son, whose name is given as "Cockermay Doucri", which is said to be Scots for "David the Foundling". They stayed three days at Rochester, and purposed to proceed next day to Canterbury (and perhaps thence to Jerusalem), but instead David wilfully misled his benefactor on a short-cut and, with robbery in view, felled him with a blow on the head and cut his throat.

The body was discovered by a mad woman, who plaited a garland of honeysuckle and placed it first on the head of the corpse and then her own, whereupon the madness left her. On learning her tale the monks of Rochester carried the body to the cathedral and there buried it. He was honoured as a martyr because he was on a pilgrimage to holy places. As a result of the miracle involving the madwoman as well as other miracles wrought at his intercession after death, he was acclaimed a saint by the people.

Veneration

In 1256 AD, Lawrence of St Martin, Bishop of Rochester, obtained the canonisation of William from Pope Alexander IV. A beginning was at once made with his shrine, which was situated first in the crypt, then in the northeast transept, and attracted crowds of pilgrims. At the same time a small chapel was built at the place of the murder, which was thereafter called Palmersdene. Remains of this chapel are still to be seen near the site of the old St William's Hospital, on the road leading by Horsted Farm to Maidstone.

The shrine of St William of Perth became a place of pilgrimage second only to Canterbury's shrine of Saint Thomas Becket, bringing many thousands of medieval pilgrims to the cathedral. Their footsteps wore down the original stone Pilgrim Steps, and nowadays they are covered with wooden steps.[4] Margaret Darcy, of Essex, in her will, expressed the wish that her servant, Margaret Staunford, should go on a pilgrimage to "Seint Willyam of Rowchester".

On 18 and 19 February 1300 AD, King Edward I gave two donations of seven shillings to the shrine. Offerings at the shrine were also recorded for Queen Philippa (1352). On 29 November 1399, Pope Boniface IX granted an indulgence to those who visited and gave alms to the shrine on certain specified days. The local people continued to make bequests through the 15th and 16th centuries.

The coat of arms of the Bishop of Rochester consists of Saint Andrew's cross with a scallop shell in its centre, which is said to represent William; Andrew being the patron saint of Scotland and scallops being the symbol of pilgrimage. St. William is represented in a wall-painting, which was discovered in 1883 in Frindsbury church, near Rochester, which is supposed to have been painted about 1256–1266.

Almighty and everlasting God, who kindled the flame of your love in the heart of your holy martyr Willian. Grant to us, your humble servants, a like faith and power of love, that we who rejoice in her triumph may profit by her example; through Jesus Christ our Lord, who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, one God, for ever and ever. Amen.

#father troy beecham#christianity#troy beecham episcopal#jesus#father troy beecham episcopal#saints#god#salvation#peace#martyrs#faith#pilgrim#pilgrimage

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Queen Katherine set out from Greenwich, with her husband and six hundred archers dressed in long, white, wide-sleeved gabardine coats and caps, on 15 June 1513. They travelled in small stages south towards Dover. There in the castle overlooking the sea, Katherine was formally appointed Queen Governor of the Realm. She was aged about 28 and was, by then, vastly experienced in her own right as a diplomat, princess and queen. Her upbringing in Spain at the side of her mother, Queen Isabella of Castile, had coloured her childhood with high politics and war.

As soon as her husband set sail for the English port of Calais, from where he was finally to launch his campaign against the French, she was to rule in his place or, rather, in his name. She could raise armies, appoint sheriffs, approve most church appointments and spend money exactly as she wished. Henry declared that he was leaving the English people in the care of a woman whose ‘honour, excellence, prudence, forethought and faithfulness’ could not be doubted. They, in turn, were instructed to obey her every command. A small council was left behind to advise her. With power now in her hands, it was time to say goodbye. Katherine and her ladies ‘made such sorrow for the departing of their lords and husbands, that it was great dolor [pain] to behold’. Most of the army was already across the other side of the Channel.

Governing England in Henry’s absence now occupied her days. There were felons to be pardoned, prebends, canons and bailiffs to be appointed, lands and annuities to be handed out, the estates of the recently deceased countess of Somerset to be dealt with and a long-running administrative spat between the archbishop of Canterbury and the bishop of Winchester to be resolved. She also, from a distance, dealt with the affairs of Calais, in Henry’s rearguard. Letters, patents, grants and writs now carried ‘teste Katerina Anglie Regina’ (‘witnessed by Catherine, Queen of England’) rather than the ‘Teste me ipso’ (‘I have witnessed this’) of Henry. She signed them ‘Katherine [or Katherina] the Qwene’.

Katherine had pressed for war, but she was still worried that her glory-seeking husband would behave recklessly, placing himself in unnecessary danger. Shortly after he had sailed she wrote to his almoner, Thomas Wolsey, anxiously begging for weekly letters to reassure her that her hot-headed husband was safe. She also wrote to her former sister-in-law Margaret of Austria, who was now regent of the Netherlands, begging her to send a doctor to be at hand for her husband. Katherine felt safer once Margaret’s father, the Emperor Maximilian – basically serving as a paid mercenary but still a far more experienced fighter than Henry – appeared at the scene of battle. Her hope now, she told Wolsey, was that ‘with his good counsel, his grace [Henry] shall not adventure himself so much as I was afraid of before’.

In August and September, Queen Katherine was faced with an invasion from the Scots, led by her brother-in-law James IV, who was married to Henry’s sister Margaret Tudor. James had threatened war with England if Henry went to war with France. Henry even recruited his sister to try to persuade her husband not to invade England while he was away in France. At the same time, Anne of Brittany, Queen of France was writing James, asking him to be her knight in shining armor and attack England. In the end, against the advice of his councilors, James decided to attack England. In August of 1513, James IV’s herald presented King Henry VIII with a written declaration of war. The king of Scotland was actually excommunicated by the Pope for breaking the Treaty of Perpetual Peace with England.

Katherine started preparing in July, as soon as news reached her that James IV of Scotland was mustering a large army. Early in August she demanded to know why the mayor and sheriffs of Gloucester had not responded to her letters asking how many men and horses they could supply. ‘News from the Borders show that the king of Scots means war,’ she said. There was no time for dallying. She ordered them to answer within fifteen days. In mid-August Katherine wrote light-heartedly to Wolsey asking him to tell Henry that ‘all his subjects be very glad, I thank God, to be busy with the Scots, for they take it for [a] pastime’. Katherine was not intimidated. She relished the challenge coming her way and had thrown herself fully into organising England’s defence. ‘My heart is very good to it,’ she said excitedly in a letter to Wolsey signed nine days before James led his army of up to thirty thousand men across the River Tweed. One of his first actions was to attack and take Norham Castle, belonging to the bishop of Durham. James had to be stopped before he marched farther south.

Surrey and his sons, Edmund and Thomas Howard, were in position by the beginning of September; their army gathered near Newcastle ready to march toward the enemy. Sir Thomas Lovell had another army at Nottingham; Katherine and her council had gathered a third in the south just in case the worst happened and James somehow got through the other two. The Queen was well prepared. She had been busy and not just, as she coyly told Wolsey, ‘making standards, banners and badges’. Katherine sent ten thousand pounds, a considerable sum of money, north to be guarded (and, presumably, used for war expenses) by the Abbot of St Mary, near York. She also sent artillery, gunners and a fleet of eight ships, including the Mary Rose, which carried additional troops, towards the Scottish border. Grain, pipes of beer, rope, cables and suits of light armour were also shipped north. For her first line of defence she would rely on the earl of Surrey and the troops he was raising in the northern counties, together with those that had arrived by sea. James had a large army, however, backed by some recently delivered and formidable modern French artillery.

Documents were drawn up, meanwhile, to declare Scotsmen living in England to be ‘enemies’; but that all Scotsmen that have married English women and have children may remain. All others would have their goods seized and their persons banished under penalty of their lives. All Frenchmen to have their goods forfeited and be committed to prison if they dwell near the sea coast; or else, if they dwell inland, to find sureties. Henry VIII – flush from his minor triumphs in France – decided to send Katherine one of his more illustrious captives, the duke of Longueville. Katherine was about to set off northwards towards the Scottish threat herself. The duke and six others with him would just have to stay in the Tower of London for a few weeks.

As the Scottish threat grew, in a letter dated 2 September to Thomas Wolsey in France, Katherine revealed that she was ready to head northwards. These short notes show that Katherine personally led what was left of the king’s artillery towards the North. In early September Katherine wrote to the Great Wardrobe (the central store of royal clothing and equipment behind Baynard’s Castle in London) demanding delivery of banners, standards and pennants for those who would march north with her. A herald and a pursuivant, dressed up in the coats of arms of England, were also to travel with her. It would be the herald’s job to deliver any formal battle challenges or other messages she might care to send the Scottish king. She took 1500 suits of armour, called Almain Rivets, on her journey – all part of her direct responsibility for organising England’s deep defence. Finally, so she might display a suitable amount of magnificence, six trumpeters with their trumpet banners were to accompany her.

Katherine began to move north with a body of troops variously described as ‘a great power’ or a ‘numerous force’. At this time she also ordered up a golden ‘headpiece with crown’, and had both a light sallet helmet and a rounded, broad-brimmed shapewe helmet (rather like an armoured sun hat) especially garnished – presumably with gold or jewels. There is no record of her being seen in armour. ‘Our queen also took the field against the Scots with a numerous force one hundred miles from here,’ reported a London-based Venetian. Peter Martyr, Katherine’s old professor, heard that “Queen Katherine, in imitation of her mother Isabel and imbued by the spirit of her father … made a splendid oration to the English captains, told them to be ready to defend their territory, that the Lord smiled upon those who stood in defence of their own, and they should remember English courage excelled that of all other nations”.

In the invasion crises of the previous reign, Henry VII had gathered his power at Kenilworth castle. In 1513, nearby Warwick was the destination of the queen, her guns and likely muster point for Lovell’s troops. Instead of seeking refuge in the secure Tower of London and letting her husband’s councillors take the lead, Katherine’s decisive action moved her closer to danger and confirmed her role as national commander. She would not have been involved in any battle that might have occurred had the Scots broken through on the border, but her determination to be nearby to organise the country’s stretched resources sent all the right signals to the people she temporarily ruled.

Prior to Sean Cunningham’s find, historians had only known that Katherine was in Buckingham, around 60 miles north of London, when she received word of Surrey’s victory. But the new evidence suggests that the queen intended to travel further north, if not directly into battle like Joan of Arc, then at least into the vicinity of combat. James IV’s army was routed at Flodden Field, near the Northumberland village of Branxton. The fighting, which began in the afternoon of September 9, was ferocious. Courageous men on both sides fell in bloody hand-to-hand combat, but gradually the tide turned away from the Scots to leave the English in control of the field. Many of the Scots, or so we read in English accounts, were so “vengeable and cruel in their fighting” that their opponents preferred to kill them rather than capture them alive, contemptuously leaving the corpses naked on the ground. Among the dead was the king: James struggled like a man possessed only to fall within a few feet of the great Surrey himself. The flower of the nobility died with him; so did the Archbishop of St. Andrews, two bishops, and two abbots and perhaps another eleven thousand or so of the more humble. English losses are estimated to have numbered about one thousand.

The impact of Flodden and its consequences was immediately felt in England. Surrey wrote at once to the Queen, informing her of the victory, and sent her James's banner and the bloody coat he had died in as trophies; Katherine duly sent them on to Henry by a herald. The body taken to London, which had been suitably bowelled, embalmed and cered. Then she gave devout thanks to God for Surrey's success, and returned in triumph to Richmond. On the way, she stayed the night at Woburn Abbey, and it was here that she took time to write to her husband:

Sir,

My Lord Howard hath sent me a letter open to your Grace, within one of mine, by the which you shall see at length the great Victory that our Lord hath sent your subjects in your absence; and for this cause there is no need herein to trouble your Grace with long writing, but, to my thinking, this battle hath been to your Grace and all your realm the greatest honor that could be, and more than you should win all the crown of France; thanked be God of it, and I am sure your Grace forgetteth not to do this, which shall be cause to send you many more such great victories, as I trust he shall do. My husband, for hastiness, with Rougecross I could not send your Grace the piece of the King of Scots coat which John Glynn now brings. In this your Grace shall see how I keep my promise, sending you for your banners a king’s coat. I thought to send himself unto you, but our Englishmens’ hearts would not suffer it. It should have been better for him to have been in peace than have this reward. All that God sends is for the best.

My Lord of Surrey, my Henry, would fain know your pleasure in the burying of the King of Scots’ body, for he has written to me so. With the next messenger your Grace’s pleasure may be herein known. And with this I make an end, praying God to send you home shortly, for without this no joy here can be accomplished; and for the same I pray, and now go to Our Lady of Walsingham that I promised so long ago to see. At Woburn the 16th of September.

I send your Grace herein a bill found in a Scotsman’s purse of such things as the French King sent to the said King of Scots to make war against you, beseeching you to send Mathew hither as soon as this messenger comes to bring me tidings from your Grace.

Your humble wife and true servant, Katharine.

Queen Katherine tactfully credits the victory against the Scots to Henry himself. She understood Henry and his desire for glory. Even while engaged in the Scottish campaign, she never forgot to congratulate him fulsomely on all that he did. According to many historians, Katherine had the intention of sending James's body (some even say "head") as a trophy to her husband, but the Englishmen thought it was too crude so she settled his bloodstained coat instead. I think Katherine’s letter is misinterpreted. In my opinion Katherine wanted to send James as a prisoner to France, in exchange for Henry sending her the Duke of Longueville – that’s what she meant by saying she intended to send the king’s person, but the stout ‘English hearts’ would not stand for it (and killed James) so she sent his bloodied coat instead. Katherine did not even dare to order the burial of James’s corpse without Henry’s agreement. She sent a message to Queen Margaret, offering her consolation for a husband killed by her own soldiers. ‘The queen of England, for the love she bears the queen of Scots, would gladly send a servant to comfort her,’ it said. Soon Friar Langley was on his way.

The island of Britain was, temporarily and for the first time, in the hands of two women. Katherine governed England as regent for her husband. It was her task to administer the victory. The newly widowed Margaret ruled in Scotland as protector for her one-year-old son, James V. The infant king had been crowned shortly after his father’s death at what, because of the tears shed for the dead left behind at Flodden, became known as the ‘Mourning Coronation’. Within a fortnight of Flodden, the talk was already of a truce. Katherine’s commanders in the north wrote recommending an end to the war. Many of the remaining Scottish nobles, however, were hankering for revenge and Katherine was asked to decide whether troops should be permanently billeted at certain points near the border. The situation was by no means stable and war could have flared again at any time.

Katherine continued to oversee negotiations for a truce with the Scots, and showed great skill in her diplomatic messages to her man on the spot, the bishop of Durham. Langley acted as an intermediary in the negotiations for a truce that was not finally signed until the following February. At the same time, Katherine instructed Lord Dacre to assert King Henry’s right to become guardian of his nephew, the young James V of Scotland – potentially re-opening the troubled English claim to overlordship of Scotland. Henry VIII also did his bit to improve relations by begging the pope for permission to bury James IV at St Paul’s, even though the latter had been excommunicated for breaking a papally sanctioned treaty of nonaggression with England.

Katherine oversaw the unwinding of the war machine, paying soldiers’ and sailors’ wages and signing off on the costs of artillery, shipping and transport. Even while at Walsingham, where she would have walked the last mile to the Virgin Mary’s shrine barefoot, she still had to oversee the day-to-day running of a country where domestic worries began to take precedence. The plague, for example, was killing three or four hundred Londoners a day. Although proud of the Scottish defeat and her own performance as regent, Katherine wanted Henry home. There would be “noo joye” here without him, she confided. On 21 October Henry sailed from Calais to Dover. He rushed eagerly home to Katherine, riding ‘in post’ to Richmond ‘where was such a loving meeting that every creature rejoiced’. They were back together again, this time as a pair of young conquerors.

There had been rumours that she was pregnant and had lost a child while Henry was away. Now was a good time to start again. According to Julia Fox we cannot know whether those ambassadors who stated that she gave birth in the autumn of 1513 were right, but it is doubtful. Certainly no baby or miscarriage is mentioned in her correspondence, and it seems unlikely that she would have risked a much-wanted child by accompanying the army from London. But her mother, Isabella I of Castile, despite being pregnant rode with the troops.

At that stage of her life, as Henry’s regime sent thousands of English soldiers to fight on the Scottish border, in France and at sea, Katherine was an ideal partner for her dynamic and aggressive husband. The chamber books and related papers can still offer much to deepen our understanding of how Henry and Katherine’s marriage developed, changed and soured over the following 25 years – a relationship that came to have a powerful influence on the course of the nation’s history.

Sources:

Catherine of Aragon, Henry’s Spanish Queen by Giles Tremlett

Sister Queens: The Noble, Tragic Lives of Katherine of Aragon and Juana, Queen of Castile by Julia Fox

Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, of the Reign of Henry VIII, Volumen 1 by J. S. Brewer

https://tudorsandotherhistories.wordpress.com/2015/09/09/a-field-of-blood-and-glory-flodden-field/

https://thefreelancehistorywriter.com/2012/10/27/the-battle-of-flodden/

https://blog.nationalarchives.gov.uk/katherine-of-aragon-and-an-army-for-the-north-in-1513/

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/when-catherine-aragon-led-englands-armies-victory-over-scotland-180975982/#.X4wBqV0fcr4.twitter

#Katherine of Aragon#Catherine of Aragon#Flodden Field#Katherine's regency#British history#Catalina de Aragon#Women in history

122 notes

·

View notes

Text

On September 25th 1237 The Treaty of York was agreed between the kings Alexander II of Scotland and Henry III of England.

The signing of the treaty was one of the major events of the reign of Alexander, it was the first time that the border between the two countries was defined.

In addition to defining the border, the treaty addressed other issues between the two Kings who had a bit of a history of making agreements with each other. Henry and Alexander were brothers-in-law as the Scottish King had married Henry’s sister Joan. The treaty was witnessed by a Papal Legate called Otho and it was written in Latin and entitled ‘Scriptum cirographatum inter Henricum Regem Anglie et Alexandrum Regem Scocie de comitatu Northumbrie Cumbrie et Westmerland factum coram Ottone Legato’. It could have been known as the ‘Treaty with the long name’ and it was signed and agreed in respect of “all claims, …up to Friday next before Michaelmas A.D. 1237.” Those other issues and claims related to Alexander’s and his predecessors’ attempts to extend Scotland’s frontier southward into England.

As it happened, the Kings of Scotland had long-standing claims to the territories of Cumberland, Northumberland and Westmorland, with David I having ruled over large tracts of those lands in the 12th Century. In fact, David I died at Carlisle, where he had spent a lot of his time. William I, David’s grandson, had acknowledged Henry II as his feudal lord in 1174, but that was largely ignored and for most of the 13th Century, Scotland retained much of its freedom and independence if not its influence in those northern parts. However, there at York in 1237, Alexander II gave up any claim to those northern counties in exchange for certain estates within them, notably in Tynedale and at Penrith, for which he swore fealty to the English King. Those estates were to be held by Alexander and his successors with certain hereditary rights and freedoms, including the prevalence of Scots Law, and the exemption of the Scottish King and all his future heirs from English Law, in those territories. In addition to the giving up of that territorial advantage, Alexander relinquished Scotland’s claim to a refund of 15,000 marks, which was due as a result of King John’s having reneged on a past arrangement with William the Lion. Never trust a medieval Englishman.

As regards border disputes, Berwick on Tweed was the subject of dispute for another two centuries after the Treaty of York was signed. The English invaded Scotland and unlawfully occupied the Scottish Royal Burgh of Berwick on Tweed on a number of occasions between 1296 and 1482. Berwick had received its founding royal charter from David I in 1124 and the Treaty of York, which has never been rescinded or repealed, in no way amended Berwick’s Scottish status. On the contrary, by its definition of the border, the treaty confirmed Berwick as being in Scotland. After Berwick was unlawfully annexed by England in 1482, there came a compromise of sorts via the 1502 Treaty of Perpetual Peace, which left Berwick under English administration, whilst it remained part of Scotland and subject to Scots Law. The Tweed border defined by the earlier Treaty of York was not altered and even after the Treaty of Union of 1707, there was no change to the border or the application of Scots Law.

That situation lasted until the Wales and Berwick Act of 1746, which unconstitutionally ordained that henceforth English Law would apply in Berwick-upon-Tweed. Significantly, that act did not incorporate Berwick into England and, in truth it wasn’t much more than a panicky reaction to the 1745/46 Jacobite Rising. That 1746 act was repealed by the fairly recent Interpretation Act of 1978, but nevertheless, Berwick remains a separate enclave under administration by the English County of Northumberland. Importantly, however, the administrative boundary near Lamberton does not represent the border, which remains as per the Treaty of York.

18 notes

·

View notes

Photo

On September 25th 1237 The Treaty of York was agreed between the kings Alexander II of Scotland and Henry III of England.

This agreement meant that Northumberland, Cumberland, and Westmorland were subject to English sovereignty, but it also set down the border between Scotland and England, that remains, more or less the same as it is to this day.

The treaty was one of a number of agreements made in the ongoing relationship between the two kings. The papal legate Otho (also known as Oddone di Monferrato) was already in England at Henry’s request, to attend a synod in London in November that year, Henry informed Otho in advance of the September meeting at York, which he attended.

The meeting between the two Kings was recorded by the contemporary chronicler Matthew Paris, who disparaged both Alexander and Otho. Paris’ false allegations against Alexander, portraying him as boorishly uncivil and aggressive, have been repeated uncritically in several historical accounts. In fact, Henry and Alexander had had a history of making agreements to settle one matter or another, and they were, by and large, cordial because the two had strong kinship ties. Alexander was married to Henry’s sister, Joan, and Alexander’s sister Margaret had married Hubert de Burgh, a former regent to Henry. Henry was a close confidante of the English King, so it is only natural he would be biased in his favour.

On 13th August 1237 Henry advised Otho that he would meet Alexander at York to conclude a peace treaty. Their agreement was reached on 25th September “respecting all claims, or competent to, the latter, up to Friday next before Michaelmas A.D. 1237”.

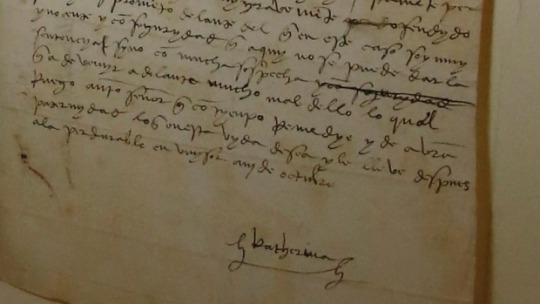

The title of the agreement is Scriptum cirographatum inter Henricum Regem Anglie et Alexandrum Regem Scocie de comitatu Northumbrie Cumbrie et Westmerland factum coram Ottone Legato (Agreement written between Henry, king of England and Alexander, king of Scotland concerning the counties of Northumberland, Cumberland, and Westmoreland, done in the presence of papal legate Otto). The particulars of the agreement are as follows:

The King of Scotland: quitclaims to the King of England his hereditary rights to the counties of Northumberland, Cumberland, and Westmorland; quitclaims 15,000 marks of silver paid by King William to King John for certain conventions not observed by the latter; and frees Henry from agreements regarding marriages between Henry and Richard, and Alexander’s sisters Margaret, Isabella, and Marjory.

The King of England grants the King of Scotland certain lands within Northumberland and Cumberland, to be held by him and his successor kings of Scotland in feudal tenure with certain rights exempting them from obligations common in feudal relationships, and with the Scottish Steward sitting in Justice regarding certain issues that may arise, and these, too, are hereditary to the King of Scotland’s heirs, and regarding these the King of Scotland shall not be answerable to an English court of law in any suit.

The King of Scotland makes his homage and fealty – de praedictis terris [in the aforementioned territories]

Both kings respect previous writings not in conflict with this agreement, and any charters found regarding said counties to be restored to the King of England.

Older historians have shown little interest in the agreement, either mentioning it in passing or ignoring it altogether, and it still does not get much mileage in contemporary histories of relations between Scotland and England. Given that the treaty established a border that is still in effect 800 years later, you’d think it would have more prominence.

15 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The 25th of September 1237 saw the signing of the Treaty of York between Scotland and England.

The border between Scotland and England was officially defined for the first time and by mutual agreement through the Treaty of York. It was signed in York by King Henry III of England and Alexander I of Scotland.

This set out the boundary of the two kingdoms as running between the Solway Firth in the west and the mouth of the River Tweed in the east. With the exception of an area around Berwick upon Tweed, which was to remain the subject of dispute for another two centuries, it fixed for the first time the border we see today.

Under the Treaty of York, Alexander II rescinded long standing Scottish claims to the counties of Northumbria and Cumbria. In addition to defining the border, the treaty addressed other issues between the two Kings who had a bit of a history of making agreements with each other. Henry and Alexander were brothers-in-law as the Scottish King had married Henry’s sister Joan.

The treaty was witnessed by a Papal Legate called Otho and it was written in Latin and entitled ‘Scriptum cirographatum inter Henricum Regem Anglie et Alexandrum Regem Scocie de comitatu Northumbrie Cumbrie et Westmerland factum coram Ottone Legato’. It could have also been known as the ‘Treaty with the long name’

15 notes

·

View notes

Photo

On September 25th 1237 The Treaty of York was agreed between the kings Alexander II of Scotland and Henry III of England.

The signing of the treaty was one of the major events of the reign of Alexander, it was the first time that the border between the two countries was defined. There's a lot of info to take in here, as you would expect, the border has been pretty fluid over the centuries.

In addition to defining the border, the treaty addressed other issues between the two Kings who had a bit of a history of making agreements with each other. Henry and Alexander were brothers-in-law as the Scottish King had married Henry’s sister Joan. The treaty was witnessed by a Papal Legate called Otho and it was written in Latin and entitled ‘Scriptum cirographatum inter Henricum Regem Anglie et Alexandrum Regem Scocie de comitatu Northumbrie Cumbrie et Westmerland factum coram Ottone Legato’.

It could have been known as the ‘Treaty with the long name’ and it was signed and agreed in respect of “all claims, …up to Friday next before Michaelmas A.D. 1237.”

Those other issues and claims related to Alexander’s and his predecessors’ attempts to extend Scotland’s frontier southward into England.

As it happened, the Kings of Scotland had long-standing claims to the territories of Cumberland, Northumberland and Westmorland, with David I having ruled over large tracts of those lands in the 12th Century. In fact, David I died at Carlisle, where he had spent a lot of his time. William I, David’s grandson, had acknowledged Henry II as his feudal lord in 1174, but that was largely ignored and for most of the 13th Century, Scotland retained much of its freedom and independence if not its influence in those northern parts.

However, there at York in 1237, Alexander II gave up any claim to those northern counties in exchange for certain estates within them, notably in Tynedale and at Penrith, for which he swore fealty to the English King. Those estates were to be held by Alexander and his successors with certain hereditary rights and freedoms, including the prevalence of Scots Law, and the exemption of the Scottish King and all his future heirs from English Law, in those territories.

In addition to the giving up of that territorial advantage, Alexander relinquished Scotland’s claim to a refund of 15,000 marks, which was due as a result of King John’s having reneged on a past arrangement with William the Lion. Never trust a medieval Englishman eh!

As regards border disputes, Berwick on Tweed was the subject of dispute for another two centuries after the Treaty of York was signed. The English invaded Scotland and unlawfully occupied the Scottish Royal Burgh of Berwick on Tweed on a number of occasions between 1296 and 1482.

Berwick had received its founding royal charter from David I in 1124 and the Treaty of York, which has never been rescinded or repealed, in no way amended Berwick’s Scottish status. On the contrary, by its definition of the border, the treaty confirmed Berwick as being in Scotland. After Berwick was unlawfully annexed by England in 1482, there came a compromise of sorts via the 1502 Treaty of Perpetual Peace, which left Berwick under English administration, whilst it remained part of Scotland and subject to Scots Law. The Tweed border defined by the earlier Treaty of York was not altered and even after the Treaty of Union of 1707, there was no change to the border or the application of Scots Law.

That situation lasted until the Wales and Berwick Act of 1746, which unconstitutionally ordained that henceforth English Law would apply in Berwick-upon-Tweed. Significantly, that act did not incorporate Berwick into England and, in truth it wasn’t much more than a panicky reaction to the 1745/46 Jacobite Rising.

That 1746 act was repealed by the fairly recent Interpretation Act of 1978, but nevertheless, Berwick remains a separate enclave under administration by the English County of Northumberland. Importantly, however, the administrative boundary near Lamberton does not represent the border, which remains as per the Treaty of York.

A final wee titbit for you is that the A1237 near York was so named after the date of the Treaty of York.

24 notes

·

View notes

Photo

On September 25th 1237 The Treaty of York was agreed between the kings Alexander II of Scotland and Henry III of England.

The signing of the treaty was one of the major events of the reign of Alexander, it was the first time that the border between the two countries was defined.

In addition to defining the border, the treaty addressed other issues between the two Kings who had a bit of a history of making agreements with each other. Henry and Alexander were brothers-in-law as the Scottish King had married Henry’s sister Joan. The treaty was witnessed by a Papal Legate called Otho and it was written in Latin and entitled ‘Scriptum cirographatum inter Henricum Regem Anglie et Alexandrum Regem Scocie de comitatu Northumbrie Cumbrie et Westmerland factum coram Ottone Legato’. It could have been known as the ‘Treaty with the long name’ and it was signed and agreed in respect of “all claims, …up to Friday next before Michaelmas A.D. 1237.” Those other issues and claims related to Alexander’s and his predecessors’ attempts to extend Scotland’s frontier southward into England.

As it happened, the Kings of Scotland had long-standing claims to the territories of Cumberland, Northumberland and Westmorland, with David I having ruled over large tracts of those lands in the 12th Century. In fact, David I died at Carlisle, where he had spent a lot of his time. William I, David’s grandson, had acknowledged Henry II as his feudal lord in 1174, but that was largely ignored and for most of the 13th Century, Scotland retained much of its freedom and independence if not its influence in those northern parts. However, there at York in 1237, Alexander II gave up any claim to those northern counties in exchange for certain estates within them, notably in Tynedale and at Penrith, for which he swore fealty to the English King. Those estates were to be held by Alexander and his successors with certain hereditary rights and freedoms, including the prevalence of Scots Law, and the exemption of the Scottish King and all his future heirs from English Law, in those territories. In addition to the giving up of that territorial advantage, Alexander relinquished Scotland’s claim to a refund of 15,000 marks, which was due as a result of King John’s having reneged on a past arrangement with William the Lion. Never trust a medieval Englishman.

As regards border disputes, Berwick on Tweed was the subject of dispute for another two centuries after the Treaty of York was signed. The English invaded Scotland and unlawfully occupied the Scottish Royal Burgh of Berwick on Tweed on a number of occasions between 1296 and 1482. Berwick had received its founding royal charter from David I in 1124 and the Treaty of York, which has never been rescinded or repealed, in no way amended Berwick’s Scottish status. On the contrary, by its definition of the border, the treaty confirmed Berwick as being in Scotland. After Berwick was unlawfully annexed by England in 1482, there came a compromise of sorts via the 1502 Treaty of Perpetual Peace, which left Berwick under English administration, whilst it remained part of Scotland and subject to Scots Law. The Tweed border defined by the earlier Treaty of York was not altered and even after the Treaty of Union of 1707, there was no change to the border or the application of Scots Law.

That situation lasted until the Wales and Berwick Act of 1746, which unconstitutionally ordained that henceforth English Law would apply in Berwick-upon-Tweed. Significantly, that act did not incorporate Berwick into England and, in truth it wasn’t much more than a panicky reaction to the 1745/46 Jacobite Rising. That 1746 act was repealed by the fairly recent Interpretation Act of 1978, but nevertheless, Berwick remains a separate enclave under administration by the English County of Northumberland. Importantly, however, the administrative boundary near Lamberton does not represent the border, which remains as per the Treaty of York.

A final wee titbit for you is that the A1237 near York was so named after the date of the Treaty of York.

32 notes

·

View notes