#anne of bohemia is my forever girl

Text

I feel like I need to share this with all of you

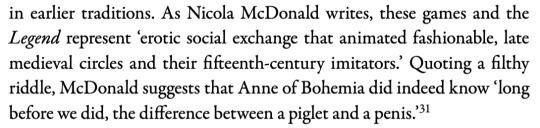

This is from a passage on Chaucer’s Legend of Good Women from Marion Turner’s biography of Geoffrey Chaucer (she’s talking about the context of the poem within Richard’s court, which is full of young people, men criticized as “knights of Venus rather than Bellona,” and a lot more women than was usual at medieval royal courts). I tried to track down the Nicola McDonald article cited, but it’s in an edited collection of articles rather than a journal and Google Books only showed a few pages of it, so I was unable to find the full context for this quote and now it’s going to haunt me forever.

From what I could piece together from Turner’s quotation and from the first couple of pages of McDonald’s article, she seems to be arguing that LGW participated in a genre of courtly pastime that included a lot of question-and-answer games about love and sex (I’ve actually taken advantage of that same trope in the novelthing, where I used it to set up a threesome). Apparently some manuscripts of LGW include the poem with texts dealing with this sort of game and other poems that resonate with the pastimes and interests of horny young courtiers, including courtly ladies.

The visible pages from McDonald that Google Books did include contain the riddle alluded to above, though. This is it:

It was probably funnier in the 1380s.

Before I double-checked the original French I thought there might have been some wordplay going on, maybe there’s a word for penis in Middle French that sounds like “piglet,” but it actually works better in English in that respect! But I think the power of the joke comes from the context: the ability of female speakers/listeners to signal their familiarity with penises and how they work would surely have given more of a frisson in the fourteenth century than it does today. A lot of scholars who have written about LGW fret about its tone: is it a serious effort to please a queenly patron who loved stories of pious women, abandoned because of the poet’s lack of interest (and her death), or a misogynist joke at her expense as Lydgate thought? What I can see of McDonald’s reading suggests an effort to cut the Gordian knot; we do know that Chaucer wrote some things explicitly meant to inspire courtly love debate (e.g., the Franklin’s Tale with its closing question) and I could see LGW fitting into that tradition. Obviously I’m not claiming for certain that this is where McDonald’s reading goes, but based on her premise, that’s where I’d take it. We know that Anne was both a pious lady and a sexually active married woman at the center of a court that enjoyed that sort of courtly love game.

I dunno what her experience with piglets was though.

#anne of bohemia#anne of bohemia is my forever girl#chaucer#richard ii#mildly nonworksafe text#oh bother

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

“…Now, if people are taught anything at all about medieval history it often is English medieval history. People with absolutely no other frame of reference can often tell you when the Norman Conquest of England took place, or the date of the signing of Magna Carta even if they don’t know exactly why these things are important. (TBH Magna Carta isn’t important unless you were a very rich dude at the time, sooooo.) If you ask people to name a medieval book they’ll probably say Beowulf even if they’ve never read it.

Here’s the thing though – England was a total backwater in terms of the way medieval people thought and was not particularly important at the time. How much of a backwater? Well, when Anne of Bohemia, daughter of my man Holy Roman Emperor Charles IV (RIP, mate. Mourn ya til I join ya.) married King Richard II of England in the fourteenth century there was uproar in Prague. How could a Bohemian imperial princess be sent to London? How would she survive in the hinterlands? The answer was she was sent along with an entire cadre of Bohemian ladies in waiting to give her people with whom she could have a sophisticated conversation.

This ended up completely changing fashion in England. Anne is the girl who introduced those sweet horned headdresses you think of when you think of medieval ladies, riding side-saddle, and the word “coach” to England, (from the Hungairan Kocs, where the cart she arrived at court the first time came from). Sweetening her transition to English life was the fact that she didn’t have to pay a dowry to get married. Instead, the English were allowed to trade freely with Bohemia and the Holy Roman Empire and allowed to be around a Czech lady. That was reward enough as far as the Empire was concerned. That’s how much England was not a thing. (The English took this insult very badly, and hated Anne at first, but since she was a G they got over it. Don’t worry.)

If England was unimportant why do we know about English medieval history and nothing else? Same reason you’re reading this blog in English right now, homes. I’m not sure if you know this, but in the modern period, the English got super super good at going around the world an enslaving anyone they met. When you’re busy not thinking about German imperial atrocities in the nineteenth century it’s because you’re busy thinking about British imperial atrocities, you feel me? So we all speak English now and if we harken back to historical things it gives us a grandiose idea of English history.

Say, then, you are trying to establish a curriculum for schools that bigs up English history, as is our want. Ask yourself – are you gonna want to dwell on an era where England was so unimportant that Czechs were flexing on it? Answer: no. You gonna gloss right over that and skip to the early modern era and the Tudors who I am absolutely sure you know all the fuck about. The second colonial-imperialist reason for not learning about medieval history is that medieval history doesn’t exactly aggrandise the colonial-imperialist system.

Yes, there are empires in medieval Europe. In addition to the Holy Roman Empire there’s the Eastern Roman Empire, aka the Byzantine Empire, whose downfall is often pointed to as one of several possible bookends to the medieval period. You also have opportunists like the Venetians who set up colonies around the Adriatic and Mediterranean, or the Normans who defo jump in boats and take over, well, anything they could get their hands on.

Notably, when these dudes got where they were going, they didn’t end up enslaving a bunch of people, committing genocide, and then funnelling all resources back to a theoretical homeland. The Normans settled down where they were eventually creating distinctive court cultures, and the Venetian colonies enjoyed a seriously high level of trade and quality of life without major disruption to local customs. Force was certainly used to take over at the outset, but it wasn’t something that resulted in the complete subjugation and deaths of millions halfway around the world from where the aggressors started.

No, the European middle ages are a lot more about local areas muddling along with smaller systems of rule. That’s why you have distinctive areas like say, Burgundy or Sicily calling their own shots and developing their own styles and fashions. Hell, even within imperial systems like the Holy Roman Empire Bavarians or Bohemians saw themselves as very much distinct peoples within an imperial system, not necessarily imperial subjects first and foremost.

You know where you would go to find some history that justifies huge imperial systems that require constant conquest and an army of slaves to keep them afloat? Ancient Rome. Remember how you got taught how great Rome was? How it was a democracy? How they had wonderful technology and underfloor heating, and oh isn’t that temple beautiful? Yeah, that’s because you were being inculcated to think that the ends of imperial violence justifies mass enslavement and disenfranchisement.

In reality, Rome wasn’t some sort of grand free democracy. Only a tiny percentage of Romans could actually vote. Women of any station certainly could not, and even men who were lucky enough to be free weren’t necessarily Roman citizens. Freedom here is particularly important because by the 1 century BCE 35 – 40% of the population of the Italian peninsula were slaves. Woo yeah democracy. I love it. And that’s not even taking into account all those times when an Emperor would suspend voting altogether.

Those slaves were busy building all the grand buildings your high school history teacher was dry jacking it about, stuffing the dormice that the rich people were reclining to eat, and basically keeping the joint running. Those slaves also necessitated the ridiculously huge army that Rome kept going because you had to get slaves from somewhere after all, so warfare had to be continuous. How uplifting.

Eagle-eyed readers will notice that this Roman nonsense is pretty much exactly what was going on during the modern colonial imperial age. You can say whatever the fuck you want about how free and revolutionary America was, for example. That doesn’t change the fact that only a handful of white property owning men could vote, and that the entire project required the mass enslavement of Africans and the genocide of Native Americans. That’s why you’ve been taught Rome is great. It helps you sleep well at night on stolen land because, really, haven’t all great societies done this? I mean without a forever war against anyone you can find, how will you keep a society going?

Our imperialist ideas about history lead to some weird historical takes. People love to tell you that no one bathed in the medieval period when medieval people had pretty much exactly the same sort of bathing culture as Romans. People laugh at medieval people believing in medical humoral theory despite the fact that Romans believed exactly the same thing and get a total pass on that front. The Roman ban on dissection is often taught as a medieval ban, shifting Roman superstition onto the shoulders of medieval people.

On-going Roman warfare is reported in glowing terms with emphasis on the “brilliance” of Roman military technique, while inter-kingdom warfare in the medieval period is portrayed as barbaric and ignorant. The Roman people who were encouraged to worship emperors as literal gods are used as an example of theoretical religion-free logical thinking, while medieval Christians are cast as ignorant for believing in God even when they are studiously working on the same philosophical queries as their predecessors. None of this makes any fucking sense.

But here’s the thing – it doesn’t need to. In a colonial imperialist society we have positioned Rome as a guiding light no matter what it’s actual practices and that’s not a mistake. It’s a design that helps to justify our own society. Further, this mindset requires us to castigate the medieval period when rule was more localised and systems of slavery had taken a precipitous dive. If only there had been more slavery, you know? Things might have been so much better.

Historical narratives and who controls them are always in flux. That old adage “history is written by the winners” comes to mind here, but that’s not exactly true. What the winners do is decide which histories are promoted, taught, and broadcasted. You can write all the history you want and if no one reads it, then it doesn’t really matter. That’s the gap that medieval history has fallen into. Colonial imperialism hasn’t figured out how to weaponise it yet, so it’s ignored. You could write this off as a “so what”, of course. Sure, maybe teaching the Roman Empire as a goal is a negative, but is ignoring medieval history really that bad a thing? You will be unsurprised to learn that I definitely think it is a bad thing, yes.

Ignorance about the medieval period is one of the things that is allowing the current swelling ranks of fascists to claim medieval Europe as some sort of “pure” white ideal. Spoiler: it was not. However, if you don’t know anything about medieval society how are you gonna argue with some chinless douche with a fake viking rune tattoo?History is always political. We use it to understand our world, but more than that we also use it to justify our world. Ignoring it helps us prop up our worst impulses, so let’s not.”

- Eleanor Janega, “On colonialism, imperialism, and ignoring medieval history.”

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

sunday snippet

So I’ve been working on Richard’s confrontation with the Lords Appellant in the Tower after Christmas of 1387, and one thing that’s surprised me a lot is how Richard’s been handling it. I think the narrative that Richard did essentially cease to rule for a few days after the meeting is basically accurate—obviously he wasn’t formally deposed because that requires more actions than the Appellants were able to take, and in my depiction of the meeting it ends on a note of “we’re gonna put you under house arrest while we decide what we’re going to do, but don’t be surprised when we overthrow you.” But the surprising part is that, while I expected Richard to have a breakdown once he got out of the meeting, he’s actually gone into strategy mode. I’ve been setting up the faultlines within the appellant coalition, and Richard is very aware of them. The meeting with Bolingbroke and Mowbray he mentions in this scene actually did happen and is attested by Walsingham and Knighton (although I don’t think either one has both men present, but hey. Dramatic license). So that’s gonna be fun and awkward but it’s gonna work.

Anyway, having Richard put up more of a fight in 1387 allows for a nice contrast with his actual deposition in 1399: I think he feels, at this point, that he has more to fight for. Anne is still alive, after all, and is an important part of his strategy here (which is why the appellants bar her from their meeting with Richard). Plus, and this is an extremely important point, the Merciless Parliament hasn’t happened yet and that’s where the trauma REALLY kicks in.

--

Anne is sitting by the fire, when Richard arrives with the guards beside him, a half-embroidered strip of linen in her lap, which she pokes at absently with her needle as she stares into the flames; she has even uncovered her hair, but when she hears the door open, she starts, dropping her needle and scrambling to pin her veil back on before the guards see her. A look of relief passes across her features when she sees Richard, followed by a look of concern—and then, as soon as the door is closed behind him and the guards are out of sight, she leaps to her feet and runs to him, throwing her arms around him, and Richard wraps his arms around her and presses her close.

After a long moment, she draws back far enough to clasp his face with both hands. “Are you all right?” she breathes.

“I don’t know,” Richard admits, and shakes his head. “They let me stay here with you, at least.”

“What happened?” Anne says. “Did you get them to see reason? They are not going to depose you, are they? They cannot, surely—”

“I don’t know, Anne,” Richard says. “Thomas and Arundel, at least, are utterly merciless. I believe Thomas wants to make himself king.”

“Pane Bože,” Anne moans, pressing her hands to her mouth. “He cannot—if he does not fear his king, surely—” She shakes her head, in turn. “If we could only get a message to John of Gaunt in time,” she says. “I know you do not trust him, but if they waited until he was away…”

“Right now, I would be willing to cast myself on his mercies,” Richard says, “rather than Thomas’s. Or, God forbid, Arundel’s. It would never get to Spain in time, though.”

“Do you think they would see me?” Anne says. “Even if they would not let me stay by your side, they might hear me out—you could not plead for mercy, as a king. But as a queen—as a woman—it is what I was made for. If I could speak to Thomas—perhaps he would listen? I know being around you makes him furious, but if I spoke to him alone, he might be calmer.”

“I don’t know,” Richard says. “He does seem to like you well enough. Remember what I told you the first time we met? He has a soft spot for pretty girls.”

For a moment, Anne beams; then, remembering the gravity of their situation, she is somber again. “I will write to him and ask for a meeting,” she says. “Right away.” She turns toward the little table in the room but stops when Richard lays a hand on her shoulder.

“You may be able to do better than that,” Richard says. With his hand on her back, he walks her back to the settle to sit by the fire. It is, after all, a cold evening. “Do you think you could convince Henry Bolingbroke and Thomas Mowbray to listen to you?”

Anne smiles again. “I think they would be easier to persuade than Thomas,” she says. “But do you think they would be able to convince Thomas of anything? Or Arundel?”

“I’m not sure,” Richard admits. “But they’re the ones having supper with us tonight, so right now they’re our best chance.”

“They are having supper with us?” Anne blinks and immediately begins adjusting her veil again.

“Not for a few hours,” Richard says. “Before compline. You’ll have plenty of time to get ready.”

“All right,” Anne says, running her hands over her head anyway to smooth the wrinkles in her veil, and not having much success. “How did you get them to agree to meet with us? I am amazed that Thomas and Arundel allowed it!”

“To be honest,” Richard says, “I am too. But I think that’s why the two of them decided to come, and I think that’s our best hope of getting out of this.”

Anne nods, but her eyes are wide and her expression is confused. “What do you mean?”

“I said before that I think Thomas wants to make himself king,” Richard says. “Despite the fact that the Mortimers, Henry, York and his sons, and, worst of all, John of Gaunt, are all ahead of him in the line of succession. He kept hinting at it throughout the meeting. And Henry definitely noticed. He may not care what happens to us, but I think he’ll be damned before he sees Thomas of Woodstock sitting on the throne. And I don’t think he’ll seize the throne for himself, no matter how badly he wants it. Not while his father lives.”

#sunday snippet#the novelthing#richard ii#anne of bohemia is my forever girl#otp: my derlyng is a bundel of myrre to me#i'm really surprised at richard's ability to pull himself together here#but not in a bad way#right now he's just trying to get through this with his life and his crown#and i think seeing the five of them be all smug has really lit a fire under him#unfortunately the next part is 'saving his friends' and that's gonna crush him#btw after this anne has a little speech about imperial elections#but this is long enough so i left it out here

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

sunday snippet (sex and candy edition)

(There’s not really any sex except for two sentences at the end that aren’t explicit)

Having finished drafting Richard’s coronation scene, I thought I’d go back and work on Anne’s while I still have the Liber Regalis pdf out. Not that I used it at all for this particular scene.

On a somewhat related note: I’m a big fan of Christopher Monk’s “Modern Medieval Cuisine” blog, in which he’s cooking his way through the Forme of Cury in preparation for a book about it, and the most recent blog post (which is about candy, hence the connection) actually concludes with a bit of what I’m just gonna call NOVELTHING FANFIC.

--

It has been dark for hours when Anne is finally finished with the banqueting, and when Richard comes to her chamber she has been dressed for bed and is sitting on the bed with two of her ladies, the tall thin one with sandy hair and the shorter one with black curls (Richard is still working on learning their names). All three of them are giggling, eating comfits and sipping wine. Clearly, she’s feeling better than he did after his own coronation, a good sign certainly. The ladies both leap to their feet, curtsying, and Richard motions to them to straighten up. Anne says something to them in their language—they all giggle some more, and the two ladies curtsy to Anne as well before leaving the chamber.

“Agnes and Margaret have been teasing me since the day of our wedding,” Anne says, picking up the bowl of comfits and patting the mattress invitingly. “But they will get married eventually and then they will see.” She grins brightly as Richard sits beside her, and feeds him a piece of candied ginger; the sweet spicy heat makes his eyes water. “Their husbands will not be quite so wonderful as mine, though,” she adds, and draws him in to kiss his lips.

Richard laughs. “I’ll find someone nice to introduce them to.” He reaches into the bowl of comfits to snag a few more—a few cinnamon pastilles and a piece of candied orange peel. “I’m glad to see you still have an appetite,” he says. “After my own coronation I thought I’d never want to eat again. I couldn’t even look at the after-dinner sweets!”

“Poor Richard,” Anne says, reaching for a sugared almond. “Thank you for coming to see me today.” She wriggles closer to him, and he wraps an arm around her as she smiles up at him. “It was a little frightening—I know why you could not come properly, but I knew you were there and that made it much easier.”

“You looked radiant,” Richard says, giving her a tight squeeze and kissing her hair. They have been married for only two days, and already it feels perfectly natural, snuggling in bed with his new wife, relaxing and eating comfits and talking about their day, even when the day involves a once-in-a-lifetime event.

Anne leans into him, resting her head on his shoulder and putting the bowl down to drape an arm around his waist. “It was frightening,” she says, “but it was also exciting. I do not know how it is for boys, and of course it is different when you are the heir to the throne, but if you are one of several sisters, you are hardly ever the center of attention. Unless someone is asking for your hand, and that does not come with a feast most of the time, and if it does you spend it worrying about not being good enough, and whether you are going to marry someone you will actually like. But now that is all over with, and I have found a wonderful husband, and I am a queen.” She looks up at him with a grin, and adds, “I think I liked it.”

Richard grins back at her. “You deserve to be the center of attention,” he says. “You certainly have mine.” He picks up the comfit bowl and feeds her a piece of candied orange peel; she takes it delicately in her mouth and captures his fingertips between her lips for a moment. Richard can feel himself flush, but in a nice way.

“You are sweet,” Anne says. “Sweeter than anything in this bowl.” She reaches up to draw him into a kiss.

“Do you know what part of the coronation ceremony I especially liked?” Richard murmurs. Anne shakes her head with an anticipatory smile. “I liked the part where he talked about the chastity of royal wedlock, or whatever it was.”

Anne giggles. “It is almost as holy as being a virgin,” she says. “My saintly ancestors will have no reason to be ashamed of me.” She rests her head on his shoulder again and cuddles close to him. “I think lying together in holy matrimony must be like a sacrament itself,” she says. “When I am close to you, I know I am close to God as well.” She stifles a yawn, without much success. “I would like to sleep a little, first, though. Before we make love. If that is all right with you?”

Richard smiles and presses a kiss to her forehead. He can smell the chrism in her hair. “Anne,” he says, “when I was crowned, Sir Simon had to carry me out of the church, and then they delayed the banquet so I could sleep. And then I threw up at the end of the night. I’m amazed by your stamina as it is.”

Anne giggles sleepily. “You were just a little boy, though,” she says. “And a king. I am sure the ceremonies are much longer for kings than they are for queens.”

“Oh, probably,” Richard says. “But if you need rest, you need rest.” He kisses Anne’s forehead again, collects the comfit bowl and puts it on the table, and then climbs back into bed to wrap his arms around her.

Later that night, between first and second sleep, Anne kisses him awake, and then climbs on top of him. They do it again in the morning.

#the novelthing#sunday snippet#richard ii#anne of bohemia is my forever girl#otp: my derlyng is a bundel of myrre to me#note also the obvious foreshadowing early on#anyway they are cute and i love them#...that was already in my tags OH WELL

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

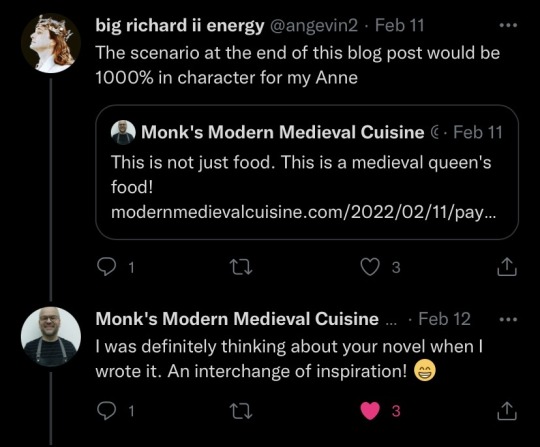

This isn’t a terribly uncommon reading of Maidstone’s Concordia—Sylvia Federico makes a similar one where she suggests that Maidstone has pretty much accidentally written Richard as a bigamist (or patron of sex workers) and Anne as a madam, so actually he ended up with a subversive poem—and I always think it’s weird. Marriage between the king and the realm is a longstanding trope, after all; I don’t think it would read as scandalous to a contemporary reader unless they were really determined. Anne’s intercession as described in the poem reads less to me as procuring an entirely separate marriage for her husband and more as essentially identifying herself with the city, taking its offenses onto herself if you will. Her intercession allows for Richard’s relationship with his subjects to be realigned with his happy and loving marriage; she’s not stepping aside so he can cheat on her with the city of London or something.

(cf. also Sebastian Sobecki’s reading of Apollonius of Tyre, which has one of the cutest endings of a scholarly article ever)

I think all of this falls into the “Anne is mostly a literary construct rather than a real person and any discussion of her is really about the male poet’s agenda” category, but also: it’s weird.

#or am i weird?#i realize i have an atypically positive reading of the concordia as far as academic takes on it go#richard ii#anne of bohemia#anne of bohemia is my forever girl#anne is not in fact a literary construct jsyk#she was a real person we just don't know too much about because of the distance of centuries#and one really hostile chronicler

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

wip wednesday (bohemian rhapsody edition)

I’m letting the Peasants’ Revolt section sit in the fridge for a bit to let the flavors meld, and also I felt like writing some Richard/Anne content, so here, have some. I think I already have more Czech cultural references than any other fictional depiction of Anne of Bohemia ever. The story she tells here is pretty accurate to the most famous version of the legend (as told by Alois Jirásek in 1894), because idk where to find the text of Cosmas of Prague’s Chronica Boemorum, which is more period-appropriate. Anyway, it’s framed here for maximum foreshadowing. You’ll know it when you see it.

--

Richard has not been to Nottingham in some time, but he has always enjoyed residing there: the magnificent deer park beside the castle, with its beautiful forests and orchards, plentiful deer, fishing ponds, falconry, and rabbit warren, is one of his favorite places. He’s been eager to visit with Anne, who is still learning the realm in their second year of marriage. Since the happy resolution of last summer’s tumultuous events, hunting and falconry have been a way for the two of them to spend time with Robert, and for Anne and Robert to grow closer to one another. Anne has shown a particular love for falconry—after all, she is, Richard had teased her, an imperial eagle. Last summer, the Duke and Duchess of York had given her the gift of a beautiful female merlin, which she had given the unusual (as far as he understood things) name of Libuše.

“She was my ancestor,” Anne had explained, when Richard asked her about it. “She was a queen, back in the pagan days, and she built the city of Prague. She was the youngest of three daughters, but her father chose her as his heir, because she was also the wisest, and she could see visions of the future. She was especially skilled at settling disputes in court. But her subjects grew angry. One man who had lost his court case stirred them up against her. He said that women cannot reason, that the people needed a strong man to rule them, and many other men agreed with him. They did not want to be ruled by a woman any longer. They insisted that she marry. But Libuše did not want these men to tell her what to do. It made her angry that they objected to her compassionate rule, and all because of her sex. So she insisted on choosing her own husband, and she had fallen in love with a plowman called Přemysl.”

“She married down!” Richard exclaimed. “Like the Emperor’s daughter who married the King of England, I suppose,” he teased her.

Anne giggled, then. “She married for love,” she said. “But Libuše knew that one day her husband would become a stern ruler, who treated his people harshly. She had the gift of prophecy, remember. If that was what they wanted, she thought, they could have it! So she told them to saddle her horse, and let it wander until it found a man plowing his fields, wearing a broken sandal, and bring him to her, for she would marry only that man. Of course, she already knew where to find him, and her horse did too. But her council did not know that. They did as she told them, and her horse went straight to Přemysl. So they brought him back as Libuše had ordered, and they were married. And the house of Přemysl—my father’s house—endures to this day.”

Richard smiled. “Bohemian women have always been remarkable, I see,” he said. “What happened to the two of them?”

“Eventually, she died,” Anne said, “but she had been right. She and Přemysl had ruled well for many years. But after she died, he became the stern and harsh ruler she had prophesied.”

“It’s a sad story, then,” Richard said. “He must have loved her so much—perhaps he couldn’t rule well without her.” He’d smiled, and kissed Anne. “They were your ancestors, you say? I think you must take after her.” And Anne had giggled and kissed him back.

#the novelthing#anne of bohemia is my forever girl#wip wednesday#otp: my derlyng is a bundel of myrre to me#české věci#extremely subtle foreshadowing

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

fic: smale fowles maken melodye (1350 words, rated G)

This fic was inspired by this fantastic drawing by @sekihamsterdiestwice! I had one particular headcanon about Richard that I felt would make for a very amusing juxtaposition with the picture, and I decided: why not write about it?

--

"Where did you even get that thing?" Robert exclaims, wincing at the discordant sounds coming from the small gittern Richard is tunelessly strumming. He is lounging with Anne on a small cushioned bench in their small enclosed garden, beneath a trellis covered in roses, a crown of roses on his head and a single rose in Anne's hair—a lovely sight, if you could somehow contrive to disengage your ears. Perhaps Anne has just such a skill, as she is leaning on his shoulder, smiling blissfully and making no sign that she's bothered by her husband's cold-blooded torture of an innocent stringed instrument. Robert makes a note to himself to ask her to teach him. Of course, she's wearing her hair in thick braids coiled over her ears and held in place by a golden hairnet, so perhaps that mitigates the worst of the effects.

"Didn't you take music lessons as a boy?" Richard says, his fingers pausing mercifully on the strings.

"Of course I did!" Robert says. "Mine actually worked, though."

"Unlike your lessons in tact and courtly manners, I see." Richard grins and punctuates his remark with another sound that might, if you were generous, be called a chord. "Are you going to come and sit with us, or aren't you?"

"We all have our strengths and weaknesses," Robert says, flopping down on the soft grass at Richard's feet.

"I think it is sweet, anyway," Anne says. "Has he never serenaded you?"

"No, thank God," Robert says, scooting out of the way just in time to avoid Richard's foot.

"A grievous oversight, on my part," Richard says. "I'll have to remedy it immediately." He resumes his strumming, accompanying himself as he sings in a light, clear tenor:

"Gais et jolis, liés, chantant et joieus..."

It would be quite lovely, really, if it could adhere to a melody for more than a few notes, and unfortunately this particular melody is a winding thread that, in Richard's mouth, quickly tangles and loses track of itself, not helped by Richard's on-the-fly efforts to modify the lyrics for a male beloved. All three are giggling when Richard breaks off after a few lines. Robert leans over to rest his head in Richard's lap, and Richard drapes an arm over his shoulder.

"Well, you tried your best," Robert says.

"That is the important part," Anne adds, leaning in and kissing Richard on the cheek.

Richard strokes Robert's hair. "Nobody tell Henry Bolingbroke, though," he says, although his good mood remains unbroken—Robert can hear the smile in his voice. Anne and himself are the only people allowed to tease Richard this way, and they both know that Richard likes it when they do. It makes him feel like a normal person, being surrounded by people he loves, who love him—whom he trusts, enough even to let his carefully-guarded dignity slip. He takes Richard's hand and presses it to his lips.

Anne leans in and half-whispers, "Mary was telling me about how she sings with her husband," and Robert mouths oh, I see and nods his head. Henry is reputedly a talented musician, although Robert finds it a little hard to believe, given that he is visibly and wholeheartedly committed to his own image as a rugged warrior, rather than some artsy-fartsy courtier-poet type, and then wonders why Richard doesn't especially enjoy his company. If he's got a softer side his wife is allowed to see, Robert is honestly relieved on her behalf.

"Maybe if we tried something simpler," he says aloud, sitting up straight. He reaches out toward Richard. "Hand me the gittern, won't you?"

Richard does so, grinning. "Ah, so you're going to serenade me then? I approve."

"Even better," Robert says, plucking a simple ostinato on the gittern. "I think you know this one, Richard. Anne, I'm guessing you don't, so I'll sing it for you first. It's a round, so we'll sing it on top of each other, eventually." He waggles his eyebrows, and Richard and Anne both giggle, Anne's cheeks turning a fetching shade of pink. When they've settled down, he begins.

"Sumer is icumen in,

Lhude sing cuccu!

Groweth sed and bloweth med

and springth the wode nu,

Sing, cuccu!"

When he's finished, Richard and Anne applaud and beam at him, and he makes the closest simulation of a bow he can when sitting cross-legged on the ground. "Let's try it together now," he says. "I'll start, and when I point to you, start singing the melody, all right?"

"Wait, wait," Anne exclaims, throwing her hands up. "This song has many words, and they are all English words, and I will never remember them all."

Anne has only been in England for a few years, and Robert knows she has been working diligently on her English, with her husband's help and sometimes his own as well. Still, he can't imagine it's an easy language to pick up, especially when you already speak five others like she does. He's heard her speak her native language before and neither he nor Richard could make even a scrap of sense of it.

"We can go over them again," Robert says, strumming a chord on the gittern. "I'll sing each line and you two repeat after me."

He begins the song again, stopping after each line so Anne (and Richard) can sing it back to him; Richard's ability to carry a tune not much improved when it's a simpler tune, and Anne's clear, warm singing voice stumbling over the unfamiliar words. But it is an old song. Nobody speaks English this way anymore, anyway.

"Why are we singing about deer farts?" Anne exclaims, after Richard has explained a particularly vexatious line, and both Richard and Robert laugh.

"Why not sing about deer farts?" Robert says. "Especially in the presence of the White Hart?"

"Hey!" Richard shoves him with his foot, and Anne giggles. "It's a spring song! With lots of—seed. And things, you know, blowing." Robert snorts, and Anne giggles even more. "Like flowers!" Richard adds. "And cuckoos! Naughty little birds, they are."

At last they're ready to try it as a round: Robert plays the ostinato on the gittern and sings the melody as though he's clinging to it for dear life. Anne comes in second, handling the melody beautifully but replacing most of the words with nonsense syllables. Finally there's Richard, who knows the words but only bounces off the melody occasionally while his voice wanders around somewhere else entirely. Every few measures they break down in giggles.

It's strangely beautiful, nevertheless.

After a few repetitions the round finally limps to a close with Richard caroling "Sing cuccu, nu!" in a way that would probably terrify a real cuckoo. Neither Robert nor Anne, however, is a cuckoo, and the two of them applaud.

"Come sit up here with us!" Richard says, afterward, taking Robert's hand and pulling him up to join them on the bench, and Robert abandons the gittern to sit beside them. Richard wraps one arm around his waist and the other around Anne's before turning to kiss first Anne and then Robert on the lips, and then the three of them sit contentedly, leaning on one another, enjoying the quiet that's occasionally broken by actual (and much more melodious) birdsong.

"Why are English poems and songs so obsessed with cuckoos, anyway?" Anne asks, after a bit.

"I told you, they're naughty little birds!" Richard says. "Like in that poem Sir John Clanvowe wrote for you."

"It's because in English it sounds like 'cuckold,'" Robert says. "Men are constantly harping on the idea of their wives cheating on them, after all."

"Surely not Sir John, though," Anne says. "He doesn't even have a wife!"

Richard and Robert both grin. "And he's true to Sir William," Richard adds, "just as you both are to me."

Robert leans in to kiss Anne's hand, and then Richard's cheek. "We all live in harmony," he says, raising an eyebrow to grin back at Richard. "Well. Figuratively."

--

Notes

I usually translate Middle English lyric into modern English, but I thought this one was too hard (and way too famous). Just assume that everything else here is "really" in French. Including the French lyrics that I kept in French. Look, what do you want from me, consistency? This is sheer fluff and I wrote it in a day.

I am assuming anyone reading this fic knows "Sumer is icumen in." My favorite version of it is this one. The other song Richard attempts is Machaut's "Gais et jolis." I tried to work in a reference to Machaut's service to Anne's grandfather, John the Blind (King of Bohemia 1323–46, and the star of Machaut's poem Jugement du roy de Behaigne) but it got too clunky, since Machaut is never actually named in the text.

An amusing summary of the debate over the meaning of bucke verteth can be read here.

#fic#richard ii#anne of bohemia is my forever girl#the exceedingly queer robert de vere#ot3: 'tis two rogues i love#my fic is not as good as the picture that inspired it but that's okay

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

wip wednesday (this bit kinda has my name in it edition)

Here’s a bit from earlier in Anne’s coronation sequence. Anne was crowned in Westminster Abbey two days after her wedding to Richard, which is why Richard’s POV here is so intensely starry-eyed (and horny). It’s all still really new to them.

It was standard practice in the Middle Ages for kings not to attend their wives’ coronations unless the two of them were being crowned together, although the Liber Regalis does contain instructions for what to do if he does want to attend. The idea, though, is that having him there would pull the focus (I have Sir Simon Burley explain this in an earlier sequence). Henry VII and Margaret Beaufort attended Elizabeth of York’s coronation in a sort of officially-unofficial way behind a curtain (I learned this from @feuillesmortes) but since nobody wrote any detailed accounts of Anne of Bohemia’s coronation, preferring to grumble about her appearance, stature, and lack of dowry, I just stuck Richard in the galleries instead.

--

The galleries in Westminster Abbey are very high up, enough that it makes Richard a little dizzy. He can see right down into the shrine of Edward the Confessor, although he tries not to look directly down, as it makes his head spin when he tries it, and the monk that Abbot Litlyngton has sent to accompany him (and probably to keep him from doing or saying anything too conspicuous, or embarrassing) puts a nervous hand on his shoulder to steady him.

“I’d stand back a little, if I were you, your Highness,” the monk says, and Richard nods a little unsteadily. It’s good advice, after all. Below, the Abbey glitters in the candlelight; Richard wonders if all the candles have made it any warmer. Upstairs, it is cold enough that Richard can see his breath.

But then the great west gates open and the procession is approaching and Richard forgets to be cold. First comes Edmund Langley, bearing the scepter, and John of Gaunt, bearing the crown, and then Anne comes into the church, escorted by Archbishop Courtenay and Bishop Braybrooke, as the barons of the Cinque Ports carefully withdraw the golden canopy they have borne over her head between the palace and the Abbey. She looks tiny, from so far away, in her purple robes with her hair falling down her back in golden-brown waves held in place by a jeweled circlet, but her very presence fills the whole nave with light and warmth.

The procession stops at the entrance to the church, and Archbishop Courtenay holds up his hands to pray over Anne.

“Omnipotens sempiterne Deus, fons et origo totius bonitatis...”

He prays that God will bless and protect Anne, and that, like the holy women Sarah and Leah and Rachel and Rebecca, she will rejoice in the fruit of her womb. Even from this height, and this distance, Richard can sense that Anne is blushing now. His own face is blazing—he remembers what Anne had said, yesterday morning. We are blessed, she had said, and he had been amazed. I think God must have meant me for you, she had also said, and Richard has no doubt that she is right. When they come together tonight to celebrate Anne’s coronation, it will also be blessed.

He probably shouldn’t think too much about it right now, though.

Below him, the two bishops are leading Anne down the long nave through the choir to the altar, which has been prepared with a pile of carpets and cushions. Anne kneels down upon these, very carefully, her hair and her purple robes flowing around her. She smooths her skirts carefully over her thighs and then raises her eyes—when her gaze falls upon Richard, beaming down on her from the galleries, she rewards him with a smile that is so radiant Richard feels he might weep. He presses his fingers to his lips and risks holding them out over the railing towards her, just for a moment, as she smiles up at him, and then she lies prostrate on the cushions and Archbishop Courtenay stands over her and blocks his view.

“Deus qui solus habes immortalitatem…” the archbishop intones. Richard is startled into unchurchly amusement when Archbishop Courtenay reaches the words proximam virginitati palmam continere queat—that she may hold the palm next to that of virginity, the heavenly reward of the faithful wife—and while Richard cannot see Anne’s face, he is certain her eyes are full of mirth. He can see her rosy-cheeked smile in his mind’s eye. Now I want to do this every night for the rest of my life, she had told him yesterday. They have just prayed for her fertility, after all. Richard smiles to himself—they have both been doing their part, and they have every intention of doing their part some more tonight, if Anne isn’t too tired after the banquet. Richard’s face is now very warm even in the cold church, and he is uncomfortably aware that if he keeps thinking along these lines he is going to embarrass himself quite severely, and in the church too. He shifts his weight uncomfortably from one foot to the other and bites his lip.

When Archbishop Courtenay has finished praying, Anne, with the support of two of the bishops, raises herself to her knees, and four noblewomen come to the altar bearing a golden canopy. Richard feels a sudden shiver, remembering his own anointing, years ago, how the air seemed to shimmer in the summer heat and the scent of the holy oil and chrism overwhelmed him. From here, he can barely smell it.

If Richard can trust his memory of time—and he’s not certain he can—it takes much less time for Anne to be anointed. He vaguely recalls that queens are not anointed in as many places as kings are. Anne is also not called upon to divest herself of her robes, which, given where Richard’s mind has persisted in going, is probably for the best. Then, almost before he knows it, the canopy is being moved away and Anne is visible again. Richard remembers wondering if he seemed different, when they took the canopy away. He had felt different. He wonders if Anne feels different. When Archbishop Courtenay has finished saying a short prayer over her, he steps aside to signal for the regalia. Anne looks up toward the galleries again, her face flushed and her eyes shining. Richard has to admit that she doesn’t look different, but he wouldn’t want her to look any different. She is perfect the way she is.

#wip wednesday#the novelthing#richard ii#otp: my derlyng is a bundel of myrre to me#anne of bohemia is my forever girl#fun fact: in that first paragraph richard is looking down into where his and anne's tomb will be#jessica barker's chapter on them in stone fidelity talks about how the tomb re-enacts their coronations and marriage#which#OH MY GOD SO MANY FEELS#also the liber regalis itself is now in the galleries#as is the wooden head from anne's funeral effigy#which i can apparently recognize from behind at a distance of about fifty feet#that's how much of a nerd i am

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

sunday snippet (plesaunte to prynces paye edition)

This is part of a long and emotional scene in which Anne and Richard hash things out after Anne discovers the nature of her husband’s relationship with Robert de Vere (although Richard and Robert have been sort of on a break since Richard got married). As you know, collective Bob, I write Richard and Anne as establishing an emotional (and physical!) connection very quickly, but this makes the revelations discussed here a lot harder for them to deal with. But it’s not actually a spoiler to tell you they work it out. ;)

Since there are definitely some people who will pick up on some of the connections with actual medieval literature (that isn’t mentioned directly) here, I will say that I’m not all that excited about readings of Pearl that treat it as an elegy for Anne of Bohemia, because the main point of them usually seems to be “Anne had a celibate marriage and died a virgin” which, no. The TEAMS editor, Sarah Stanbury, has the more sensible take that the poem is steeped in the courtly aesthetic associated with her even if it’s not “about” her specifically, which I do like more as a reading. In any case I am absolutely not above exploiting the pearl imagery (which genuinely was associated with Anne) for emotional effect.

--

Anne sniffles, rubs at her nose with her sleeve a bit, and raises her eyes to him. “I did not expect that you would love me, when I came here,” she says. “I know that I have value as a bride, because of who my father was. And I have been educated to be a queen.” She bites her lip, and continues, “But I know I am not beautiful, and that I brought no dowry, and that after six months I am not yet with child. But—when I am with you, I am happy, in a way I do not think I have ever been.” She looks up at him and smiles, a tiny, shy little smile. It makes Richard want to kiss her, but this is not the time. “It would have been easier if I had never felt that you loved me,” she says, leaning against his shoulder and sighing. “But I did. Perhaps I still do. I do not know what to think, Richard.”

“When you came in,” Richard says, “you told me that you would believe what I told you, when you asked me about Robert. And you do believe me, right?”

Anne nods.

“Then, please, Anne—believe me now. I don’t want you to always be obedient, or to sacrifice your own happiness for my sake. I don’t want you to be meek and retiring all the time just because you feel you have to. I know I’ve hurt you—I didn’t know how to tell you any of this, and I know that doesn’t make it right. Anne, I want to make it right. But I also need to ask you to trust me that I love you. I think I always have, almost since I saw you.”

Anne straightens up a little so that she can look him in the face. Her warm brown eyes meet his; after a long moment, she gasps softly, smiles a little through her tears, and lowers her eyes. “Even though I was cold and sneezed on you, and even though you paid twenty thousand florins for me?”

Richard leans in so that their foreheads are almost touching, lifts her hand to his, and kisses it. “Shouldn’t a man sell everything he has, for a pearl of great price?”

“Pane Bože!” Anne exclaims, her eyes wide with amazement and her free hand flying to her mouth. She draws back, but not, Richard thinks, to avoid him.

“Anne?” He is still holding her hand; he presses it between his own, and she does not pull it away.

“My mother used to tell me that I did not know my own worth,” she says. “I would tell her, of course I do. I am the daughter of the Emperor, and the sister of the King of the Romans. And she would shake her head.” She smiles a little, and bites her lip. “Before I left, I was worried. Because I had no dowry, and I was afraid I would not be enough, in myself, for you, and that you might grow to resent me for it. And my mother, to comfort me, said that I was to marry a wise king, who would give all he could for a pearl of great price.”

“And so you are,” Richard says. “My pearl of great price. Everything I’ve said in the past few months—everything we’ve done, all of that was real. All of it was worth it.”

Anne watches his face, and now her expression is serene and her gaze is steady. Her eyes are shining, but that’s from the tears. “Have you ever had a moment,” she says, “when you had no doubt at all? When you knew what God had made you for?”

Richard nods, in his turn. “Once, when I rode out to the crowd at Smithfield. And again, on our wedding night.”

“I told you that morning,” Anne says, “that God meant me for you. After that first night, I knew my body was made for you—that I was ordained for you. In doubting you, I have doubted Him.” She takes Richard’s hands and clasps them in hers. “I want to have faith.”

#the novelthing#otp: my derlyng is a bundel of myrre to me#richard ii#anne of bohemia#anne of bohemia is my forever girl#john bowers still sucks tho

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

wip wednesday (you get guilt! and you get guilt! edition)

Didn’t do a sunday snippet this week because I’d just posted a fic on Saturday (you should go read it! It’s here!) so here’s an extra-long WIP Wednesday excerpt. This takes place during the Appellant Crisis—Richard has just had an extremely threatening meeting with the five of them, but he’s been able to persuade Henry Bolingbroke and Thomas Mowbray to have supper with him and Anne that evening (I’ve posted a few bits of that scene before). In this scene, Richard and Anne have been strategizing, but at the moment they’re mostly just kind of bummed out.

I’ve written a lot in this space about my Richard’s guilt about the Peasants’ Revolt, so I don’t think I need to belabor the point further.

CW for discussion of pregnancy loss, so I’ve put the cut in early. Dedicated readers of my fiction writing (if any) may recognize the hypothetical scenario Anne describes early in this passage.

--

She covers his hand with her own, where it rests against her belly, and they sit together in silence for a while. Then Anne sighs, deep and heartfelt, and interlaces her fingers tightly with Richard’s, clasping his hand in both of hers.

“Are you all right?” Richard says.

“I cannot help thinking,” Anne says. “Richard, if I had given you a child by now—” She swallows hard. “I have lost three babies, since we were wed. And if one of them had lived—” She presses her lips tightly together, shakes her head. “You would have an heir. And the appellants would try to use him against you, as your great-grandmother used your grandfather against your great-grandfather. And they cannot do that, and it is because all of our children have died in my womb, before they were fully formed in body or soul.” She looks up at him again, and her eyes are wet. “I know that whatever happens is the will of God,” she continues, “and I try to submit myself to it, whatever he allows to happen. But if I were to lose you—” She presses his hand more tightly in hers. “I do not know how I would go on. I would sit and weep endlessly, like Niobe. Who lost all of her children!” She shakes her head, releasing Richard’s hand, and turns her eyes heavenward. “It is a cruel mercy He has shown us,” she says. “Perhaps we should do penance, when this is over, when we are safe.”

Richard wraps his arms around Anne, pulling her close and resting his cheek against her hair. “Perhaps this is my penance,” he says. “Not yours. You haven’t caused any of this, Anne.”

“I have been complicit in securing a divorce under false pretenses,” Anne says, “on behalf of someone who is a friend. I can see that it was a sin, but I thought it was all for the best. Robert did not love Philippa, but he does not love Agnes either, not in the way he loves you. Perhaps not even in the way he loves me.” She shakes her head. “I could not abandon my dear friends to shame and disgrace, and so I helped to wrong Philippa. And now Philippa is rid of her husband, and she has every right to be glad of it, and the entire English nobility taking up her cause.” She straightens up, agitated, and Richard releases her. At a loss for something to do with her hands, she picks up her discarded embroidery from the settle and examines it for a moment, fishing for her needle among the cushions. When she finds it, she stabs it into the cloth, piercing the heart of a blackwork imperial eagle. “And—God forgive me, but it is all so much!” she cries, at last. “So much punishment, and we meant so little wrong, to have our lives ruined.”

“Anne,” Richard says, “you don’t need to take the blame for this onto yourself. God knows I have my own sins, my own failings—though they’re not the ones the Appellants accuse me of. I suppose that’s the worst of it. The lords are just as guilty of those sins as I am.”

Anne takes his hands again and looks up at him. “What do you mean?” she says.

“I’ve told you before,” Richard says, “that in the days when the commons rose up against us all, they looked to me for redress of the wrongs the lords had done—including my own forefathers. They had a watchword, you know: ‘King Richard and the true commons.’ And I heard their words, and I knew what the Lord had put me here to do: I was here to free my people from bondage.”

“I remember,” Anne says. “You were so brave. You are still brave, miláčku.”

“Everyone looked to me, then—the nobles and the councils and the great men of the city were too afraid to act, and the commons saw me as the only person who could help them. And I wanted to help them, Anne, I truly did. And then, once the crowds had dispersed and the smoke had cleared and the leaders of the rebellion were swinging from the gallows or looking down upon the city from poles, the nobles and the councils and the great men of the city swept back in and revoked all my promises for me. I suppose I knew that I would be punished for it, someday, and I suppose this must be it. I failed the least of my people, and now I’m facing retribution at the hands of the greatest, the same men who caused me to break my promises in the first place.” He sighs a little, shaking his head in disgust. “I suppose I did the same, when I tried to use my lord Tresilian against my enemies, knowing how vicious he had been in persecuting the commons. I thought—” He looks at Anne, who is still holding his hands, although her face is impassive, non-judgmental. “I thought it was for the best,” he says. “I only wonder—does the Lord mean for me to be chastened, or overthrown altogether?”

“Perhaps He is working through Bolingbroke and Mowbray,” Anne says. “It may be through them that you will keep the throne.”

Richard nods, and then snorts. “What a perfectly humiliating situation,” he says. “Henry Bolingbroke is going to preen about this for the rest of our lives, probably. Do you suppose the Lord has a sense of humor, that this is all some sort of incomprehensible joke? It’s beginning to feel like it.”

Anne straightens and reaches up to stroke his cheek. “It is all right,” she says. “If there is a need to humble ourselves before them, I will do so. It is no shame for a woman to plead. Even a queen.”

Richard bends in to press his forehead to hers. “If I have hope that the Lord will not destroy me entirely,” he says, “it’s because He sent you to me. I can’t think of a greater sign of His favor.” He cups her face gently, and kisses her lips, and Anne wraps her arms around his waist and kisses him back.

“I love you,” Anne whispers, “whatever happens. Let us be ready for them.”

#wip wednesday#the novelthing#richard ii#anne of bohemia is my forever girl#otp: my derlyng is a bundel of myrre to me#johan the mullere hath ygrounde smal smal smal

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

sunday snippet (young and sweet, only seventeen edition)

(okay, in this snippet our dancing queen has not yet reached the ABBA-approved age, since she’s actually only 15, but CLOSE ENOUGH)

Anyway I’ve been writing a lot of grim Peasants’ Revolt stuff but all the same I thought I’d post a happier moment from six months later, albeit not one completely free of awkwardness.

--

Whenever she has the chance, Anne reaches under the table and squeezes Richard’s hand, and he squeezes back and rubs his thumb over her knuckles. It always makes her giggle. She is beaming throughout the feast, her cheeks rosy and her eyes shining. Richard wonders how everything stands up to the imperial court, if what passes for splendor in England would be ordinary in her homeland—they have no trouble making conversation, but while Anne is usually eager to talk about her father’s and brother’s glittering court back in Prague, she refrains from making comparisons today, when it’s the most splendor she’s ever seen in England. But perhaps it doesn’t matter: whenever she lays eyes on him her expression is one of sheer bliss. In moments when the diners seem to be mostly distracted, Richard catches Anne’s hand and kisses it. There’s never a moment where nobody is looking, though; it draws affectionate laughs from the assembled crowd every time. Once he catches Robert’s eye, where he is seated with Philippa. Philippa smiles brightly at Richard and Anne; Robert nods briefly, enough to fulfill his duty of obeisance to his lord, and then averts his eyes. Richard frowns for an instant—now that he is married himself, he doesn’t see why Robert is so glum about the state of matrimony. Philippa has always seemed agreeable enough, after all, though of course she can’t possibly be as wonderful as Anne, who distracts him from this rather unsettling reverie by motioning to him and then feeding him a piece of candied quince.

It is well into the evening when the feasting is over, and the tables are cleared away and then there’s dancing in the hall: stately caroles and lively saltarellos and robust estampies. Anne may be sturdily built, but she is light on her feet nevertheless. Richard can scarcely take his eyes off her as they step and twirl and hop and clap, her face flushed with excitement and exertion and her hair swinging out behind her. Whenever they begin a circle dance her hand slips into his eagerly, no matter how sweaty his palms are. They are, perhaps, fortunate: they only miss their steps once or twice while caught up in one another, and Henry of Derby manages to avoid crashing directly into the two of them as a result, thanks to an effort of strength and balance heroic enough that Richard can’t be too angry at him, not at his wedding, not with Anne’s hand clasping his own. Richard, once again, ignores the stray tittering from the wedding guests and vows to build new dancing chambers in all of their palaces, just so he can see her like this as often as possible for as long as they both live.

#the novelthing#richard ii#anne of bohemia is my forever girl#sunday snippet#otp: my derlyng is a bundel of myrre to me#i love them so much#poor robert though#it's okay they will all work things out

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

WIP Wednesday is BACK, BABY

There was a post going around a few days ago about how Terry Pratchett (GNU) set his writing goals at only 400 words a day and yet look at how much he wrote, and I saw that and went “hey, I am trying to write a novel and that is a thing I can do,” especially since someone had just asked me how much more of it I had to write and I was like “...” and they were someone who’s really excited about reading it which only added to that.

So! Sharing bits of stuff I’m working on generally motivates me to continue working so I’m bringing back WIP Wednesday specifically for novelthing stuff. Currently I’ve been fleshing out the wedding scene (previously lacking its first half) because, idk, I wanted to write Richard/Anne cuteness. Thus, this.

--

The snow has already blanketed the streets and the roofs of London when the day of the royal wedding dawns, in the way of winter mornings when the darkness, still half-bright with the promise of snow, fades gradually into a dark grey and then a pale one. Richard, watching it happen, has comforted himself by reminding himself that Anne must be watching it too, even if the condition of the streets wouldn’t have required an early departure even for her and her escort to cross the short distance from the Tower to Westminster. His mother has reminded him that Anne will be more nervous than he is—it can be frightening, being a young bride. She probably hasn’t slept much herself.

Richard doesn’t anticipate that either of them will sleep much tonight, either.

Right now, though, his feet are growing damp and numb against the cold stone of the church porch. It has been cleared at least twice, and the messengers have assured everyone that the bridal party is in sight, but the snow has continued falling all morning, dusting the ground and creeping into his shoes. He looks down at his feet, watching the snowflakes catch in the openwork patterns for a moment before melting into his fine scarlet hose—perhaps closed shoes might have been more practical on a day like this, even with pattens on, but Richard wouldn’t hear of it. He’s dressed in a rich gown of blue cloth-of-gold, with a high neck and long sleeves lined in sable, over a scarlet cotehardie, an ensemble he’s quite pleased with; he’s not about to wear boring shoes to his own wedding, not when he wants to look his best for Anne and all of the people from the imperial court. He can warm his feet later.

And then the herald trumpets sound: the bridal party is here, their unfamiliar banners snapping in the wind—Bohemian banners, German banners, Polish banners carried before noblemen, ladies in elaborate headdresses, fanning out to take their places. Anne’s maids of honor, in their brightly colored gowns and jeweled chaplets, precede her, and then they too take their places before the church steps and Anne is approaching.

When Richard had brought Anne into London, only a few days ago, three maidens had showered them both with flakes of gold leaf; the snowflakes that fall around her now become her every bit as much. She is draped in furs, just as she had been at their first meeting at Leeds castle. Richard’s heart had gone out to her then, rumpled and sniffly as she was after a long and arduous journey. Now she is resplendent in an ermine-lined mantle over a red surcoat, embroidered all over with imperial eagles in gold and lions rampant in white, and an emerald-green gown patterned with rosemary leaves, her hair falling past her waist in deep golden-brown waves. The golden crown on her head blooms with pearls and rubies and sapphires, shimmering even in the thin light of the winter morning. She looks every bit the queen—his queen, his wife—and when she lays eyes on him her smile outshines even the glitter of her garments. Her cheeks are a beautiful rosy pink, whether with pride or with the cold winter air Richard can’t say and doesn’t care. He smiles back at her until the little muscles at the back of his head hurt.

#the novelthing#wip wednesday#richard ii#anne of bohemia#anne of bohemia is my forever girl#otp: my derlyng is a bundel of myrre to me#historical teenage marriage for ts#purple prose purple prose so much purple prose#i don't describe clothes that much in this thing except for fancy occasions#and given *them* it is actually fairly significant#anyway they are cute and i love them

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

things that make me super crabby

This passage in Christopher Fletcher’s book about Richard II and medieval manhood. The book on the whole is a useful corrective to takes on Richard that are basically “Richard was just totally immature and that’s why he was useless” and it does point out that Richard basically had to fight to be seen as a man rather than a boy. But the only substantial thing it says about his marriage to Anne of Bohemia is this, and it’s really quite stunningly misogynist:

He even SAYS IT’S MISOGYNIST, which doesn’t stop him from going on to say that now that he was rid of his useless, expensive, barren wife, he was able to do Manly Shit by invading Ireland.

And, like. There’s the funeral and the destruction of Sheen but also: Richard’s attendants wore Anne’s livery at his second wedding. I’m not buying this whole “Richard must have secretly resented her for emasculating him by her failure to have children” reading.

(as a side note, I hate when people say that a historical person “must have felt” a certain way if it’s not clearly obvious that they would have)

Kristen Geaman makes the argument, incidentally, that Richard and Anne’s contemporaries probably did see Richard as more at fault for their childlessness and that the constant treatment of him as immature was an expression of that—thus his emphasis on chastity as a widower (married eventually to an underage bride and thus committed to celibacy for quite a while) to the extent that he impaled his arms with those of Edward the Confessor, since celibacy could be seen as a form of manly self-control. She’s a little more persuaded than I am by the suggestion first put forth by Katherine Lewis that the Confessor thing was meant to retcon his first marriage as celibate even though, as Geaman herself has proved, it wasn’t (Fletcher’s book precedes her articles on how Anne coped with infertility, so he wouldn’t have been aware that she continued to seek medical and spiritual intervention until the end of her life and may have had at least one miscarriage). But I think the idea that Richard was anxious about his image because of his lack of children makes sense, and there’s no real evidence that he ever held it against Anne. There are lots of instances of kings and queens who were driven apart by fertility problems—after all, that’s something that happens to couples even when national stability doesn’t depend on them having babies—and it doesn’t seem like Richard and Anne were among them. And, like, I know Fletcher’s book is about masculinity but you don’t have to just pick up period-typical misogynist assumptions and run with them!

(BTW Geaman also points out that, based on surviving accounts, Anne’s Bohemian entourage was not especially wasteful or rapacious, they were just scapegoated on account of being immigrants. Mark Ormrod, who is definitely not especially romantic about Richard and Anne, gestures in the same direction here. Agnes Launcekrona was at the center of a big scandal but a number of them assimilated and stayed in England even after Anne died.)

#richard ii#anne of bohemia#anne of bohemia is my forever girl#male historians stop objectifying her challenge#in my novel/ficverse richard and anne both sort of blame themselves for their infertility#and are very supportive of the other one#there's a bit where anne compares herself to the rocky soil from the parable of the sower and it's really sad#(at least i think it is but then i wrote it)#hi i'm lea and i go off on a tear a lot about stupid stuff people say about anne#but people keep saying stupid stuff#kristen geaman is a friend of mine#she asked me to give feedback on her monograph#which i have done and i can say:#it's really good#i will give it to all my friends for christmas after it comes out#(actually i won't because the books in the series it's from are expensive)#(but i will recommend it to everyone because it's gonna be great)#infertility for ts#miscarriage for ts

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

wip wednesday (unhealthy snacking habits edition)

In my writing I’m actually sort of bouncing back and forth between the aftermath of the Peasants’ Revolt in 1381 and Richard and Anne’s East Anglian spring break trip in 1383 (which isn’t going to be shown in excruciating detail but there’s a couple of incidents I want to get in, including their visit to the shrine of Our Lady of Walsingham, and the incident at Ely where one of their attendants is struck by lightning (he got better but then five years later the Lords Appellant killed him). It has thematic reasons, I promise.

Anyway this next bit isn’t from either of those but is from the polyamory arc, after Richard and Anne have reconciled properly (there are several lengthy emotional scenes that precede this bit so now they’re happy again). The next step is bringing Anne and Robert closer together, which is what I’m using the Walsingham trip for.

--

Anne’s reflected face opens her eyes after a moment, looking up to his own reflected face, and her cheeks flush a little. “I wanted to be alone,” she says, “while I waited for you.” She lowers her eyes again, her blush reddening. “I have missed having you in my bed.”

“And I’ve missed being there,” Richard says. He returns the comb so he can wrap his arms around Anne’s shoulders and lean against her, burying his face in her hair. It smells of sage and lavender.

“I was thinking,” Anne says. “It is midsummer now, so Lent was not too long ago. Only a month after we were married.”

“Right,” Richard says. “A very short month, as I recall.”

Anne giggles. “Exactly!” she says. “And I do not know about your confessor, but mine became very exasperated with me, eventually.”

“Oh, mine too,” Richard says. “He said that if he heard any more about that, he’d require bread-and-water penance. No more almsgiving.”

“I think giving up food would be easier than giving you up,” Anne says. She turns halfway in her chair and draws him down for a kiss. “It is not just man who does not live by bread alone,” she adds, giving him a heavy-lidded smile before turning to reach into a bowl on the table beside her so that she can feed him a cherry. Then she watches intently as Richard spits the stone carefully into his hand, handing him a little dish so he can dispose of it. It already contains a number of cherry stones, because Anne is addicted to cherries, even eating them raw, although everyone knows raw fruit is bad for the humors. She takes a cherry herself and bites it in half carefully to avoid the stone; it stains her lips in a manner Richard finds irresistible. He bends in to kiss her again.

“I have forgotten what I was talking about,” Anne whispers, gazing into his eyes after they’ve drawn apart for breath.

“I suppose we were talking about penance,” Richard says.

Anne breaks into a radiant grin. She finishes the half-eaten cherry in her hand before continuing, “What I was thinking, before, was—of course I should have known you really do like sharing my bed, because if you did not, you would have had an excuse to avoid it. And I do not think I was the only one of us who stumbled, this past Lent.”

“You absolutely were not,” Richard says, smiling. “As your husband, I may owe you a debt, but it’s one I will always pay gladly, and with a willing heart.”

“Then,” Anne says, rising from her chair, “I think I will request a payment now.” She draws him down for another kiss as her fingers find the laces of his robe.

“Does this mean you forgive me?” he murmurs against her lips.

“I do,” she whispers back. “I already have.” She kisses him again, and then takes his hands to pull him toward the bed.

#the novelthing#richard ii#anne of bohemia is my forever girl#otp: my derlyng is a bundel of myrre to me#ot3: 'tis two rogues i love#wip wednesday

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Carolyn Collette, Performing Polity: Women and Agency in the Anglo-French Tradition, 1385–1620 (Brepols, 2006), pp. 99–100

#anne of bohemia#anne of bohemia is my forever girl#male critics and historians do such a bad job writing about her#*beats the drum and yells 'ANNE WAS A PERSON AND SHE MATTERED'*#'ALSO SHE AND RICHARD WERE PARTNERS POLITICALLY AS WELL AS DOMESTICALLY'

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

male scholars stfu about Anne of Bohemia challenge

A friend of mine sent me this, from Alfred Thomas’ new book about Richard II’s court and Bohemian culture. Thomas has written several books that are actually kind of similar to this, with progressively diminishing returns, and a lot of his writing about medieval English literature revolves around the idea of Richard and Anne having a celibate marriage, although back in 2013 Kristen Geaman wrote about a letter from Anne that demonstrates pretty conclusively that they did not. This book, published fairly recently, is the first time he’s actually cited her and his take is, um, not great:

Takeaways from this:

1. We can’t assume Anne and Richard had sex just because Anne writes that she was grieving her lack of children but also optimistic about her prospect of having children* in the future! That doesn’t prove anything! It could have been a diplomatic fib that she put in the letter (to her equally childless brother) even though she didn’t have to mention it! Or she could have been a total idiot who didn’t know that you have to have sex to make babies! THE WORLD MAY NEVER KNOW.

2. What Richard really loved about Anne was her bloodlines, because he’d obviously wanted to be emperor from square one, starting when he was 13.

3. Richard’s memorials for his mother-in-law also had nothing to do with Anne as a person. They certainly couldn’t have been a gesture Richard made for his wife who had recently lost her mother! They were all about his imperial ambitions and prestige.

I mean. Yes, I know we don’t know the specifics of Richard and Anne’s day-to-day relationship. We don’t know what he loved about her and I would certainly never argue that the appeal of an imperial bride wasn’t a major motivator for Richard to commit to the marriage despite the lack of obvious material gain. But it seems really unlikely that her cultural cachet and Richard’s imperial ambitions were completely at the heart of it, and I know that while it’s hard to balance the personal and the political in scholarly writing and while the two things would go hand in hand at the highest levels of society, there’s got to be a way to do it that acknowledges that Richard and Anne did have an actual personal relationship as well and that the closeness and contentedness they manifestly had stemmed from the two of them as people, because so much of the writing about the political side just gives the impression of objectifying Anne under the assumption that obviously Richard must have objectified her. We can acknowledge that we don’t know what she was like as a person without losing sight of the fact that she was a person.

*This point isn’t mentioned above, probably because Alfred Thomas is really committed to the idea that Richard and Anne had a celibate marriage and her expectation that she would have a child eventually doesn’t fit in with that, even though it requires him to privilege the work of male poets over Anne’s own words.

#anne of bohemia#richard ii#anne of bohemia is my forever girl#male historians stop objectifying her challenge#...i already had that as a tag#but like#she surely had agency even if the specific means by which she exercised it are lost

13 notes

·

View notes