#apologies for the godawful font/formatting on the chart

Text

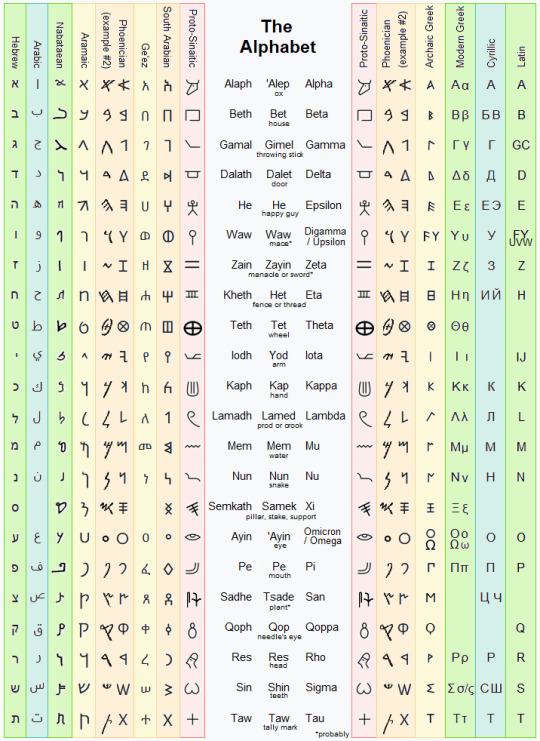

history of the latin alphabet I guess

Act I: Early Alphabet

As the Neolithic era gave way to the Bronze Age, people were increasingly living in cities and needed some kind of record-keeping. The human brain might be able to remember that you owe Eshanak a goat in exchange for twenty measures of grain, but when you're running a bustling metropolis' Ye Olde Goat Shoppe and have to track goats payable and goats receivable for hundreds of people, the grey matter starts to falter. So ancient accountants were like, "I shall draw these signs to represent goats and grain, alongside tally marks. As well, I shall come up with a mark for Eshanak's Feed and Seed Store, with whom we often do custom," and you're off to the races. More and more symbols get invented and standardized, and pretty soon you can say things like "I, the Pharaoh of Kemet, have erected this grand obelisk in commemoration of my reign," instead of just counting goats.

Logographic writing systems have advantages and disadvantages. On one hand, you don't necessarily need to know the spoken language. You see the sign for sun, you know it means sun. A French person writes down "98", you don't need to know what "quatre-vingt-dix-huit" means. On the other hand, you need to memorize a symbol or combination of symbols for like every goddamn concept in existence. And if you don't know a symbol, you can't "sound it out" on your own.

Many people did not like this, because it is nice to be able to use written language without having to basically get a PhD in it, so simpler systems arose. At one point, probably inspired by similar systems that were floating around at the time, some Semitic day laborers in Egypt decided to think of every consonant they could, all the buhs and duhs and puhs and tuhs, and copy down a hieroglyph for each one. "D is for DOOR," they said. "Where I have drawn a DOOR in the text, do not say the entire word DOOR. Instead, make only the initial DUH sound." Thus, they only had to memorize a couple dozen signs.

This alphabet was taken home by the day laborers to Canaan, where it later spread all over the place via some Canaanites we know as Phoenicians, who loved sailing new places and meeting new people.

Intermission: Vowels

In many Semitic languages, due to reasons I don't fully understand, word roots lean pretty heavily on consonants over vowels. We, for instance, might have a word like "like", where if we wrote it LK we wouldn't know if it was supposed to be like or look or lick or lock or lake. That happens in Semitic languages, but it's less common -- you can often get by without vowels. Still happens, though, so they had the idea of having some letters pull double-duty, like our "Y". Is it a vowel or a consonant? Well, funny story, if you sit around making "yuh" sounds to yourself, you can eventually reach the conclusion that it kind of does both. Try dragging out the "y" in "yes", you get "eeee-uhh-ess". Try saying Ian and the yuh shows up in the middle ("ee-yan"). Same thing with oo and wuh. This is more relevant to modern Semitic writing, but was somewhat present in the original Phoenician and probably influenced which letters Greek repurposed as vowels.

Act II: Greek

Greeks NEED their vowels. Can't live without them. The Phoenicians handed their script over like "This is a Bet (house). It used to look more like a real house floorplan, but we simplified it for faster, neater writing. This is a Dalet (door)," and the Greeks were like "Beta, Delta, got it. And this one's Alpha? And this one's just 'E'? A simple E -- an e 'psilon', if you will?" and the Phoenicians were like "uh, it's actually [Glottal-stop]'aleph and He," and the Greeks were like "Yeah, that's what I said?" and voila, there are vowels.

Some other changes the Greeks made include:

Many symbols flipped due to being written left-to-right instead of right-to-left. Also, Greeks love symmetry as much as they love vowels, so tended to make symbols more symmetrical.

Glottal stop consonants 'Alef and 'Ayin became vowels Alpha and O (the latter later split into little O, Omicron, and big O, Omega). One of the two H noises (and much later the second) became the vowel E. Iota was used only as a vowel, since they didn't have the consonant yuh sound.

They did have both oo and wuh sounds, and wanted separate signs for them, so Waw was split into Digamma (consonant, head of the symbol is bent to the right so it looks like two Gammas) and U (vowel, drawn as "Y"), which was added to the end of the alphabet and later named "simple U"/Upsilon (or Ypsilon). Then later they were like "Huh, guess we don't use that consonant sound anymore? Wine is just 'ine'?" and got rid of Digamma. But not fast enough. The Etruscans cribbed it first.

Greeks kept both Kappa and Qoppa as kuh sounds (there was a difference in the original Semitic). Later they would realize this was dumb and drop Qoppa--again, not fast enough.

Greeks [long sigh] took in Samek (suh), Tsade (tsuh), and Shin (shuh), and then had trouble telling them apart. They dropped Tsade/San entirely. They presumably misattributed the name Samek to Shin, which they called Sigma and gave a suh sound. Then they (the eastern Greeks, anyway) decided the now-nameless O.G. Samek symbol should make a /ks/ sound (why???) and called it Xi.

There were a lot of different regional variations of the Greek alphabet at this time, which were later eliminated as the modern Greek alphabet solidified. For instance, the western variant, instead of turning Samek into Xi, took it out entirely and threw a /ks/ sound written as "X" in after Upsilon at the end of the alphabet. This western variant is the one the Etruscans inherited.

Act III: Etruscan

My knee-jerk reaction is to talk about how the Etruscans fucked it up, but that's not fair to them. They did a pretty good job establishing the alphabet in Italy. It's not their fault they didn't make a distinction between guh and kuh. It's just…

"sorry for accidentally inventing the letter C" "some crimes can't be forgiven"

One fun thing they did that I like quite a lot: Instead of cluelessly imitating the clueless Greek imitation of the Semitic letter names, the Etruscans just put each sound up alongside a vowel, essentially making our current "el, em, en, oh, pe" pronunciations. But there was a rule! Consonants you can drag out, like ffff and ssss, got put after the vowel. Consonants you make once and they're done, like p- t- k- (called plosives), got put before it. Modern changes in pronunciation and some letters getting dropped/added have messed this up in several spots, but it largely holds true. In case you've ever wondered why the alphabet isn't sung Le Me Ne Oh Pe.

Also, Digamma pronounciation has moved from wuh to vuh. The Romans are soon going to change it to fuh because this letter is a neverending nightmare.

Act IV: Latin

Let's check in on the alphabet line-up.

𐌀 𐌁 𐌂 𐌃 𐌄 𐌅 𐌆 𐌇 𐌉 𐌊 𐌋 𐌌 𐌍 𐌏 𐌐 𐌒 𐌓 𐌔 𐌕 𐌖 𐌗

A B K/G D E F Z H I/Y K/G L M N O P K/G R S T U/W KS

Romans: "Hey, does this letter make a /k/ sound or a /g/ sound?" Etruscans: "Yes." Romans: "Cool, alright. Let's take all three k/g symbols and make convoluted grammar rules about which of them gets used based on the following vowel."

These rules gradually faded, with K mostly being used in Greek loanwords, Q just being used before U, and C being used for everything else. Romans didn't use the Z sound much either, so they gave it some thought and decided the reasonable thing to do would be to remove it from the alphabet, under the rationale that--well, actually, the reason recorded in Roman histories is that Appius Claudius (of the Appian Way) hated the Z sound because he thought it caused you to make the look of a death rictus, but I'm sure it was that first thing. Anyway, there was fortunately a different Roman dude around this time who said "Why don't we put a downstroke at the tip of this C, and that one can be our /g/ sound?" so they moved this new symbol "G" into Z's old spot.

The letter that makes a puh sound, originally sort of a crook shape, started to be drawn curled in tight enough that it looked like P. But "P" was already the symbol of the letter that went ruh; so, to distinguish them, they added a leg to ruh ("P") and made "R". I feel like there was a more graceful and less confusing way they could have done this.

Update on Waw's demon children: Claudius (a different one, this guy's an emperor) tried adding an upside-down F to the alphabet to represent the W sound, but it didn't take. Sorry, buddy, you tried. Oh, and the Romans have taken Upsilon (Y) from Greek. "Wait, don't we already have an Upsilon?" No, the Latin "Y" lost its "stem" a long while back and is now normally drawn like U or V. It still makes a U/W sound. Sorry, I saved that update for the "Waw's demon children" section. "But that's still an Upsilon, though. Why do they need to re-import Upsilon drawn with a stem when they've still got Upsilon drawn without one?" Because Greek Upsilon has evolved into a weird vowel that bears more phonetic resemblance to I, and the Romans want to call it "Greek I" ("I Graeca") and use it in their cool Greek loanwords. FINE, I GUESS. At least they brought Z back home with it.

As the "classical" Latin era ends, the alphabet looks like this.

A B C D E F G H I K L M N O P Q R S T V X Y Z

Intermission: Lowercase

Over time, Greek and its derived alphabets made "miniscule" letters, messy little scribbles that were much faster to write than ALL CAPS. People now use the miniscule forms for most writing, but have developed specific grammatical rules to use majuscule for important things like beginnings of sentences, names, etc.

Act V: Catching up to the Present

I'm not going to list every weird-ass letter adopted by every European country, but here are some notable things that happened that help explain the modern English alphabet.

In various Romance languages, C, instead of being pronounced /k/, started being pronounced like "tsh"/"ch" or "ts" when used before the vowels e/i/y. Wikipedia says this inexplicable nonsense is called "palatalization". In English and a few other languages, these sounds later softened to "s". Instead of instituting any kind of reform here, we just decided C would continue to make both noises. Thanks, I hate it.

Simultaneously, G palatalized as a "dzh" sound (think d + the sound in the middle of "vision") in front of e/i/y. At least this one gave us the apple of discord that is the GIF debate.

[deep breath] Waw's descendents include F, U, and Y. F is still F. A doubled U started being used to denote a wuh sound, though sometimes the runic glyph Wynn was used instead. U and V split so that the curved version is the vowel and the pointy version is the consonant. Y (formerly "Greek I") is still a vowel, though by the time of Middle English its sound has merged with normal I ("ee") entirely; in Middle English, Y started being used as a consonant in place of obscure letter Yogh for a "yuh" sound (perhaps because the sounds ee and yuh are related); it was also sometimes used by printers in place of thorn (þ), hence "ye olde".

People had long been putting a fun little curvy tail on the letter i when they felt like it needed some pizazz. In the 16th century, some Germanic people decided to split these into two letters, with the original being the vowel (ee) and the curly-tailed variant the consonant (yuh). Well done! This long-overdue innovation spread through northern Europe into Baltic and Slavic alphabets, and then slammed headlong into the goddamn Romance languages that decided to use J as a "dzh" sound because that's how they pronounce "yuh" now I guess. (Speakers of Romance languges, and also British people who say Tjchewsday, and also I suppose all of us who say "didja": Why do you keep cramming tshzjch sounds into everything?) This divide in "J" pronunciations exists to this day.

The default Latin alphabet now looks like this.

A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z

2 notes

·

View notes