#augustus at the tomb of alexander the great

Text

Lionel Royer (French, 1852-1926)

Augustus at the Tomb of Alexander the Great, 1878

#Lionel Royer#french art#french#augustus#augustus at the tomb of alexander the great#1800s#art#fine art#european art#classical art#europe#european#fine arts#oil painting#europa#mediterranean#classic art#neoclassical art#neoclassical#neoclassicism#french neoclassical#neoclassical painting

462 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lionel Royer - Augustus at the tomb of Alexander The Great, 1878.

11 notes

·

View notes

Note

Real dumb question…have we ever found any Roman emperors corpses or tombs like we have with some of the pharaohs? (Alexander where are youuuuuuuuuu?) like where is Augustus Caesar final resting place?

Yes, we know exactly where the Roman Emperors are entombed, their mausoleums, such as Hadrian's Mausoleum, the Mausoleum of Augustus and so on, they're mainly located in Rome and one was opened for re-entry for the first time in 2000 years.

Augustus or rather, Octavian's Mausoleum was opened to the public.

Alexander the Great was a Greek ruler by the by, he was first entombed in Memphis, then Alexandria, while his Tomb was destroyed around the 4th century, we know his final resting place was his greatest city.

16 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Still Life with Armour by Mariano Fortuny y Madrazo + Statue of Lucius Caesar (son of Julia the Elder & Marcus Agrippa) at Corinth, Archaeological Museum + Tomb of Alcetas in Termessos (modern Turkey) + The Maison Carrée (French: "square house") was dedicated in Nemausus to Gaius and Lucius.

For the difference between the human personality and individuality of repeated earth lives see The Influence of Spiritual Beings Upon Man: Lecture VI by Rudolf Steiner

LUCIUS CAESAR

Livia left no corresponding confession. Nor would she have, since in fact no evidence connects her with the deaths of Marcellus, Marcus Agrippa, Gaius and Lucius Caesar, Agrippa Postumus, Germanicus—or even Augustus. Frequently Livia was hundreds of miles away when her ‘victim’ died of fever or a battle-wound. On the principle of ‘Where there’s a will, there’s a way’, distance apparently proved no obstacle to this mistress of the dark side. In almost every instance her weapon was poison. Against both reason and probability, we are asked to believe that, Mazzini-like, she ‘chopped down the family tree’.

—Matthew Dennison, Livia, Empress of Rome

ALCETAS

Alcetas was the brother of Perdiccas and the son of Orontes from Orestis. He is first mentioned as one of Alexander the Great's generals in his Indian expedition. On the death of Alexander, Alcetas was a strong supporter of his brother Perdiccas. At Perdiccas' orders, in 323 BC Alcetas murdered Cynane, the half-sister of Alexander the Great, as she wished to marry off her daughter Eurydice to Philip Arrhidaeus, the nominal king of Macedon. At the time of Perdiccas' murder by his own troops in Egypt in 321 BC, Alcetas was with Eumenes in Asia Minor engaged against Craterus. The Perdiccas' army revolted from him and joined Ptolemy. They condemned Alcetas and all of Perdiccas' supporters to death. (Source)

#Lucius Caesar#Mariano Fortuny y Madrazo#Roman history#Livia#Livia Drusilla#Marcus Agrippa#Julia the Elder#Julia Augusti#Augustus#Octavian#Alcetas#Alexander the Great#Matthew Dennison#Perdiccas#spiritual science#anthroposophy

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Indeed any ancient temple

But it is not the Pantheon, nor indeed any ancient temple, which served as the original type for the Gothic churches of Europe down to the ascendency of the Petrine type at the end of the sixteenth century. Nothing in the history of architecture is better established than the evolution of the Gothic Cathedral out of the civil basilicas of the ancient world. The whole course of that evolution can be traced step by step at Rome, in Santa Maria Maggiore, St. Paul’s without the walls, St. John Lateran, St. Clement’s, St. Agnes’, St. Lawrence, and the older churches of the basilican type. Thus with the basilicas, extant, converted, or recently destroyed, as the matrix of the Gothic churches from the fifth to the fifteenth centuries, and the Pantheon as the matrix of the neo-classical churches from the fifteenth to the nineteenth century, we feel ourselves at Rome in the head-waters from which we can trace the flow of all modern architecture.

If the Pantheon be historically the central building in Rome, it is by no means amongst the oldest monuments. Nor are the walls of Roma quadrata, nor the first structures of the Palatine. The Egyptian obelisks carry us back to a time almost as remote from the Pantheon as the Pantheon is from us. The oldest, perhaps, date from the Pharaohs who built the Pyramids, and they were made to adorn the temple of the Sun on the banks of the Nile, thence were brought by the first Caesars to adorn a circus, or to give majesty to a mausoleum, then thrown down and cast aside in Christian ages as monuments of heathendom and savage shows. Again they were restored in the classical revival after a thousand years of neglect, and set up to witness to the pride of popes and adorn the capital of Christendom mystical bulgaria tours.

Vast monoliths

What an epitome of human history in those vast monoliths, the largest of which is thirty-six feet higher than Cleopatra’s needle on the Thames, and is more than three times its weight; for a thousand years witnessing the pro-cessions of Egyptian festivals, then for some centuries wit-nesses of the spectacles and luxury of the Imperial city, then for a thousand years cast down into the dust, but too vast to be destroyed, and then set up again, with the blessings of popes and the ceremonies of the Church, crowned with the symbol of the Cross, to witness to the grandeur of the successor of St. Peter. They have looked down — these eternal stones — on Moses and Aaron, on Pharaohs and Greeks and Persians, on Alexander and Julius, on Peter and Paul, on Charlemagne and Dante, on Michael Angelo and Raphael. These stones were venerable objects before history began; they have been objects of wonder to the three great religions, three races, and three epochs of civilisation.

One can forgive destructive municipalism much for at last rescuing from ignoble uses the burial-places of the Caesars. There are no edifices in Rome more interesting to the historian than those vast mausolea — the grandest and most imposing tombs that exist—the mausoleum of Augustus, that of Hadrian, of Caecilia Metella, the Pyramid of Cestius. That of Augustus, for a hundred years the burial-place of the Caesars and their families, then a castle of the Colonnas, the scene of endless civil wars, afterwards a common theatre for open-air plays, is now at last recovered, to be preserved as a monument of antiquity.

0 notes

Photo

Indeed any ancient temple

But it is not the Pantheon, nor indeed any ancient temple, which served as the original type for the Gothic churches of Europe down to the ascendency of the Petrine type at the end of the sixteenth century. Nothing in the history of architecture is better established than the evolution of the Gothic Cathedral out of the civil basilicas of the ancient world. The whole course of that evolution can be traced step by step at Rome, in Santa Maria Maggiore, St. Paul’s without the walls, St. John Lateran, St. Clement’s, St. Agnes’, St. Lawrence, and the older churches of the basilican type. Thus with the basilicas, extant, converted, or recently destroyed, as the matrix of the Gothic churches from the fifth to the fifteenth centuries, and the Pantheon as the matrix of the neo-classical churches from the fifteenth to the nineteenth century, we feel ourselves at Rome in the head-waters from which we can trace the flow of all modern architecture.

If the Pantheon be historically the central building in Rome, it is by no means amongst the oldest monuments. Nor are the walls of Roma quadrata, nor the first structures of the Palatine. The Egyptian obelisks carry us back to a time almost as remote from the Pantheon as the Pantheon is from us. The oldest, perhaps, date from the Pharaohs who built the Pyramids, and they were made to adorn the temple of the Sun on the banks of the Nile, thence were brought by the first Caesars to adorn a circus, or to give majesty to a mausoleum, then thrown down and cast aside in Christian ages as monuments of heathendom and savage shows. Again they were restored in the classical revival after a thousand years of neglect, and set up to witness to the pride of popes and adorn the capital of Christendom mystical bulgaria tours.

Vast monoliths

What an epitome of human history in those vast monoliths, the largest of which is thirty-six feet higher than Cleopatra’s needle on the Thames, and is more than three times its weight; for a thousand years witnessing the pro-cessions of Egyptian festivals, then for some centuries wit-nesses of the spectacles and luxury of the Imperial city, then for a thousand years cast down into the dust, but too vast to be destroyed, and then set up again, with the blessings of popes and the ceremonies of the Church, crowned with the symbol of the Cross, to witness to the grandeur of the successor of St. Peter. They have looked down — these eternal stones — on Moses and Aaron, on Pharaohs and Greeks and Persians, on Alexander and Julius, on Peter and Paul, on Charlemagne and Dante, on Michael Angelo and Raphael. These stones were venerable objects before history began; they have been objects of wonder to the three great religions, three races, and three epochs of civilisation.

One can forgive destructive municipalism much for at last rescuing from ignoble uses the burial-places of the Caesars. There are no edifices in Rome more interesting to the historian than those vast mausolea — the grandest and most imposing tombs that exist—the mausoleum of Augustus, that of Hadrian, of Caecilia Metella, the Pyramid of Cestius. That of Augustus, for a hundred years the burial-place of the Caesars and their families, then a castle of the Colonnas, the scene of endless civil wars, afterwards a common theatre for open-air plays, is now at last recovered, to be preserved as a monument of antiquity.

0 notes

Photo

Indeed any ancient temple

But it is not the Pantheon, nor indeed any ancient temple, which served as the original type for the Gothic churches of Europe down to the ascendency of the Petrine type at the end of the sixteenth century. Nothing in the history of architecture is better established than the evolution of the Gothic Cathedral out of the civil basilicas of the ancient world. The whole course of that evolution can be traced step by step at Rome, in Santa Maria Maggiore, St. Paul’s without the walls, St. John Lateran, St. Clement’s, St. Agnes’, St. Lawrence, and the older churches of the basilican type. Thus with the basilicas, extant, converted, or recently destroyed, as the matrix of the Gothic churches from the fifth to the fifteenth centuries, and the Pantheon as the matrix of the neo-classical churches from the fifteenth to the nineteenth century, we feel ourselves at Rome in the head-waters from which we can trace the flow of all modern architecture.

If the Pantheon be historically the central building in Rome, it is by no means amongst the oldest monuments. Nor are the walls of Roma quadrata, nor the first structures of the Palatine. The Egyptian obelisks carry us back to a time almost as remote from the Pantheon as the Pantheon is from us. The oldest, perhaps, date from the Pharaohs who built the Pyramids, and they were made to adorn the temple of the Sun on the banks of the Nile, thence were brought by the first Caesars to adorn a circus, or to give majesty to a mausoleum, then thrown down and cast aside in Christian ages as monuments of heathendom and savage shows. Again they were restored in the classical revival after a thousand years of neglect, and set up to witness to the pride of popes and adorn the capital of Christendom mystical bulgaria tours.

Vast monoliths

What an epitome of human history in those vast monoliths, the largest of which is thirty-six feet higher than Cleopatra’s needle on the Thames, and is more than three times its weight; for a thousand years witnessing the pro-cessions of Egyptian festivals, then for some centuries wit-nesses of the spectacles and luxury of the Imperial city, then for a thousand years cast down into the dust, but too vast to be destroyed, and then set up again, with the blessings of popes and the ceremonies of the Church, crowned with the symbol of the Cross, to witness to the grandeur of the successor of St. Peter. They have looked down — these eternal stones — on Moses and Aaron, on Pharaohs and Greeks and Persians, on Alexander and Julius, on Peter and Paul, on Charlemagne and Dante, on Michael Angelo and Raphael. These stones were venerable objects before history began; they have been objects of wonder to the three great religions, three races, and three epochs of civilisation.

One can forgive destructive municipalism much for at last rescuing from ignoble uses the burial-places of the Caesars. There are no edifices in Rome more interesting to the historian than those vast mausolea — the grandest and most imposing tombs that exist—the mausoleum of Augustus, that of Hadrian, of Caecilia Metella, the Pyramid of Cestius. That of Augustus, for a hundred years the burial-place of the Caesars and their families, then a castle of the Colonnas, the scene of endless civil wars, afterwards a common theatre for open-air plays, is now at last recovered, to be preserved as a monument of antiquity.

0 notes

Photo

Indeed any ancient temple

But it is not the Pantheon, nor indeed any ancient temple, which served as the original type for the Gothic churches of Europe down to the ascendency of the Petrine type at the end of the sixteenth century. Nothing in the history of architecture is better established than the evolution of the Gothic Cathedral out of the civil basilicas of the ancient world. The whole course of that evolution can be traced step by step at Rome, in Santa Maria Maggiore, St. Paul’s without the walls, St. John Lateran, St. Clement’s, St. Agnes’, St. Lawrence, and the older churches of the basilican type. Thus with the basilicas, extant, converted, or recently destroyed, as the matrix of the Gothic churches from the fifth to the fifteenth centuries, and the Pantheon as the matrix of the neo-classical churches from the fifteenth to the nineteenth century, we feel ourselves at Rome in the head-waters from which we can trace the flow of all modern architecture.

If the Pantheon be historically the central building in Rome, it is by no means amongst the oldest monuments. Nor are the walls of Roma quadrata, nor the first structures of the Palatine. The Egyptian obelisks carry us back to a time almost as remote from the Pantheon as the Pantheon is from us. The oldest, perhaps, date from the Pharaohs who built the Pyramids, and they were made to adorn the temple of the Sun on the banks of the Nile, thence were brought by the first Caesars to adorn a circus, or to give majesty to a mausoleum, then thrown down and cast aside in Christian ages as monuments of heathendom and savage shows. Again they were restored in the classical revival after a thousand years of neglect, and set up to witness to the pride of popes and adorn the capital of Christendom mystical bulgaria tours.

Vast monoliths

What an epitome of human history in those vast monoliths, the largest of which is thirty-six feet higher than Cleopatra’s needle on the Thames, and is more than three times its weight; for a thousand years witnessing the pro-cessions of Egyptian festivals, then for some centuries wit-nesses of the spectacles and luxury of the Imperial city, then for a thousand years cast down into the dust, but too vast to be destroyed, and then set up again, with the blessings of popes and the ceremonies of the Church, crowned with the symbol of the Cross, to witness to the grandeur of the successor of St. Peter. They have looked down — these eternal stones — on Moses and Aaron, on Pharaohs and Greeks and Persians, on Alexander and Julius, on Peter and Paul, on Charlemagne and Dante, on Michael Angelo and Raphael. These stones were venerable objects before history began; they have been objects of wonder to the three great religions, three races, and three epochs of civilisation.

One can forgive destructive municipalism much for at last rescuing from ignoble uses the burial-places of the Caesars. There are no edifices in Rome more interesting to the historian than those vast mausolea — the grandest and most imposing tombs that exist—the mausoleum of Augustus, that of Hadrian, of Caecilia Metella, the Pyramid of Cestius. That of Augustus, for a hundred years the burial-place of the Caesars and their families, then a castle of the Colonnas, the scene of endless civil wars, afterwards a common theatre for open-air plays, is now at last recovered, to be preserved as a monument of antiquity.

0 notes

Photo

Indeed any ancient temple

But it is not the Pantheon, nor indeed any ancient temple, which served as the original type for the Gothic churches of Europe down to the ascendency of the Petrine type at the end of the sixteenth century. Nothing in the history of architecture is better established than the evolution of the Gothic Cathedral out of the civil basilicas of the ancient world. The whole course of that evolution can be traced step by step at Rome, in Santa Maria Maggiore, St. Paul’s without the walls, St. John Lateran, St. Clement’s, St. Agnes’, St. Lawrence, and the older churches of the basilican type. Thus with the basilicas, extant, converted, or recently destroyed, as the matrix of the Gothic churches from the fifth to the fifteenth centuries, and the Pantheon as the matrix of the neo-classical churches from the fifteenth to the nineteenth century, we feel ourselves at Rome in the head-waters from which we can trace the flow of all modern architecture.

If the Pantheon be historically the central building in Rome, it is by no means amongst the oldest monuments. Nor are the walls of Roma quadrata, nor the first structures of the Palatine. The Egyptian obelisks carry us back to a time almost as remote from the Pantheon as the Pantheon is from us. The oldest, perhaps, date from the Pharaohs who built the Pyramids, and they were made to adorn the temple of the Sun on the banks of the Nile, thence were brought by the first Caesars to adorn a circus, or to give majesty to a mausoleum, then thrown down and cast aside in Christian ages as monuments of heathendom and savage shows. Again they were restored in the classical revival after a thousand years of neglect, and set up to witness to the pride of popes and adorn the capital of Christendom mystical bulgaria tours.

Vast monoliths

What an epitome of human history in those vast monoliths, the largest of which is thirty-six feet higher than Cleopatra’s needle on the Thames, and is more than three times its weight; for a thousand years witnessing the pro-cessions of Egyptian festivals, then for some centuries wit-nesses of the spectacles and luxury of the Imperial city, then for a thousand years cast down into the dust, but too vast to be destroyed, and then set up again, with the blessings of popes and the ceremonies of the Church, crowned with the symbol of the Cross, to witness to the grandeur of the successor of St. Peter. They have looked down — these eternal stones — on Moses and Aaron, on Pharaohs and Greeks and Persians, on Alexander and Julius, on Peter and Paul, on Charlemagne and Dante, on Michael Angelo and Raphael. These stones were venerable objects before history began; they have been objects of wonder to the three great religions, three races, and three epochs of civilisation.

One can forgive destructive municipalism much for at last rescuing from ignoble uses the burial-places of the Caesars. There are no edifices in Rome more interesting to the historian than those vast mausolea — the grandest and most imposing tombs that exist—the mausoleum of Augustus, that of Hadrian, of Caecilia Metella, the Pyramid of Cestius. That of Augustus, for a hundred years the burial-place of the Caesars and their families, then a castle of the Colonnas, the scene of endless civil wars, afterwards a common theatre for open-air plays, is now at last recovered, to be preserved as a monument of antiquity.

0 notes

Photo

Indeed any ancient temple

But it is not the Pantheon, nor indeed any ancient temple, which served as the original type for the Gothic churches of Europe down to the ascendency of the Petrine type at the end of the sixteenth century. Nothing in the history of architecture is better established than the evolution of the Gothic Cathedral out of the civil basilicas of the ancient world. The whole course of that evolution can be traced step by step at Rome, in Santa Maria Maggiore, St. Paul’s without the walls, St. John Lateran, St. Clement’s, St. Agnes’, St. Lawrence, and the older churches of the basilican type. Thus with the basilicas, extant, converted, or recently destroyed, as the matrix of the Gothic churches from the fifth to the fifteenth centuries, and the Pantheon as the matrix of the neo-classical churches from the fifteenth to the nineteenth century, we feel ourselves at Rome in the head-waters from which we can trace the flow of all modern architecture.

If the Pantheon be historically the central building in Rome, it is by no means amongst the oldest monuments. Nor are the walls of Roma quadrata, nor the first structures of the Palatine. The Egyptian obelisks carry us back to a time almost as remote from the Pantheon as the Pantheon is from us. The oldest, perhaps, date from the Pharaohs who built the Pyramids, and they were made to adorn the temple of the Sun on the banks of the Nile, thence were brought by the first Caesars to adorn a circus, or to give majesty to a mausoleum, then thrown down and cast aside in Christian ages as monuments of heathendom and savage shows. Again they were restored in the classical revival after a thousand years of neglect, and set up to witness to the pride of popes and adorn the capital of Christendom mystical bulgaria tours.

Vast monoliths

What an epitome of human history in those vast monoliths, the largest of which is thirty-six feet higher than Cleopatra’s needle on the Thames, and is more than three times its weight; for a thousand years witnessing the pro-cessions of Egyptian festivals, then for some centuries wit-nesses of the spectacles and luxury of the Imperial city, then for a thousand years cast down into the dust, but too vast to be destroyed, and then set up again, with the blessings of popes and the ceremonies of the Church, crowned with the symbol of the Cross, to witness to the grandeur of the successor of St. Peter. They have looked down — these eternal stones — on Moses and Aaron, on Pharaohs and Greeks and Persians, on Alexander and Julius, on Peter and Paul, on Charlemagne and Dante, on Michael Angelo and Raphael. These stones were venerable objects before history began; they have been objects of wonder to the three great religions, three races, and three epochs of civilisation.

One can forgive destructive municipalism much for at last rescuing from ignoble uses the burial-places of the Caesars. There are no edifices in Rome more interesting to the historian than those vast mausolea — the grandest and most imposing tombs that exist—the mausoleum of Augustus, that of Hadrian, of Caecilia Metella, the Pyramid of Cestius. That of Augustus, for a hundred years the burial-place of the Caesars and their families, then a castle of the Colonnas, the scene of endless civil wars, afterwards a common theatre for open-air plays, is now at last recovered, to be preserved as a monument of antiquity.

0 notes

Photo

Indeed any ancient temple

But it is not the Pantheon, nor indeed any ancient temple, which served as the original type for the Gothic churches of Europe down to the ascendency of the Petrine type at the end of the sixteenth century. Nothing in the history of architecture is better established than the evolution of the Gothic Cathedral out of the civil basilicas of the ancient world. The whole course of that evolution can be traced step by step at Rome, in Santa Maria Maggiore, St. Paul’s without the walls, St. John Lateran, St. Clement’s, St. Agnes’, St. Lawrence, and the older churches of the basilican type. Thus with the basilicas, extant, converted, or recently destroyed, as the matrix of the Gothic churches from the fifth to the fifteenth centuries, and the Pantheon as the matrix of the neo-classical churches from the fifteenth to the nineteenth century, we feel ourselves at Rome in the head-waters from which we can trace the flow of all modern architecture.

If the Pantheon be historically the central building in Rome, it is by no means amongst the oldest monuments. Nor are the walls of Roma quadrata, nor the first structures of the Palatine. The Egyptian obelisks carry us back to a time almost as remote from the Pantheon as the Pantheon is from us. The oldest, perhaps, date from the Pharaohs who built the Pyramids, and they were made to adorn the temple of the Sun on the banks of the Nile, thence were brought by the first Caesars to adorn a circus, or to give majesty to a mausoleum, then thrown down and cast aside in Christian ages as monuments of heathendom and savage shows. Again they were restored in the classical revival after a thousand years of neglect, and set up to witness to the pride of popes and adorn the capital of Christendom mystical bulgaria tours.

Vast monoliths

What an epitome of human history in those vast monoliths, the largest of which is thirty-six feet higher than Cleopatra’s needle on the Thames, and is more than three times its weight; for a thousand years witnessing the pro-cessions of Egyptian festivals, then for some centuries wit-nesses of the spectacles and luxury of the Imperial city, then for a thousand years cast down into the dust, but too vast to be destroyed, and then set up again, with the blessings of popes and the ceremonies of the Church, crowned with the symbol of the Cross, to witness to the grandeur of the successor of St. Peter. They have looked down — these eternal stones — on Moses and Aaron, on Pharaohs and Greeks and Persians, on Alexander and Julius, on Peter and Paul, on Charlemagne and Dante, on Michael Angelo and Raphael. These stones were venerable objects before history began; they have been objects of wonder to the three great religions, three races, and three epochs of civilisation.

One can forgive destructive municipalism much for at last rescuing from ignoble uses the burial-places of the Caesars. There are no edifices in Rome more interesting to the historian than those vast mausolea — the grandest and most imposing tombs that exist—the mausoleum of Augustus, that of Hadrian, of Caecilia Metella, the Pyramid of Cestius. That of Augustus, for a hundred years the burial-place of the Caesars and their families, then a castle of the Colonnas, the scene of endless civil wars, afterwards a common theatre for open-air plays, is now at last recovered, to be preserved as a monument of antiquity.

0 notes

Photo

Indeed any ancient temple

But it is not the Pantheon, nor indeed any ancient temple, which served as the original type for the Gothic churches of Europe down to the ascendency of the Petrine type at the end of the sixteenth century. Nothing in the history of architecture is better established than the evolution of the Gothic Cathedral out of the civil basilicas of the ancient world. The whole course of that evolution can be traced step by step at Rome, in Santa Maria Maggiore, St. Paul’s without the walls, St. John Lateran, St. Clement’s, St. Agnes’, St. Lawrence, and the older churches of the basilican type. Thus with the basilicas, extant, converted, or recently destroyed, as the matrix of the Gothic churches from the fifth to the fifteenth centuries, and the Pantheon as the matrix of the neo-classical churches from the fifteenth to the nineteenth century, we feel ourselves at Rome in the head-waters from which we can trace the flow of all modern architecture.

If the Pantheon be historically the central building in Rome, it is by no means amongst the oldest monuments. Nor are the walls of Roma quadrata, nor the first structures of the Palatine. The Egyptian obelisks carry us back to a time almost as remote from the Pantheon as the Pantheon is from us. The oldest, perhaps, date from the Pharaohs who built the Pyramids, and they were made to adorn the temple of the Sun on the banks of the Nile, thence were brought by the first Caesars to adorn a circus, or to give majesty to a mausoleum, then thrown down and cast aside in Christian ages as monuments of heathendom and savage shows. Again they were restored in the classical revival after a thousand years of neglect, and set up to witness to the pride of popes and adorn the capital of Christendom mystical bulgaria tours.

Vast monoliths

What an epitome of human history in those vast monoliths, the largest of which is thirty-six feet higher than Cleopatra’s needle on the Thames, and is more than three times its weight; for a thousand years witnessing the pro-cessions of Egyptian festivals, then for some centuries wit-nesses of the spectacles and luxury of the Imperial city, then for a thousand years cast down into the dust, but too vast to be destroyed, and then set up again, with the blessings of popes and the ceremonies of the Church, crowned with the symbol of the Cross, to witness to the grandeur of the successor of St. Peter. They have looked down — these eternal stones — on Moses and Aaron, on Pharaohs and Greeks and Persians, on Alexander and Julius, on Peter and Paul, on Charlemagne and Dante, on Michael Angelo and Raphael. These stones were venerable objects before history began; they have been objects of wonder to the three great religions, three races, and three epochs of civilisation.

One can forgive destructive municipalism much for at last rescuing from ignoble uses the burial-places of the Caesars. There are no edifices in Rome more interesting to the historian than those vast mausolea — the grandest and most imposing tombs that exist—the mausoleum of Augustus, that of Hadrian, of Caecilia Metella, the Pyramid of Cestius. That of Augustus, for a hundred years the burial-place of the Caesars and their families, then a castle of the Colonnas, the scene of endless civil wars, afterwards a common theatre for open-air plays, is now at last recovered, to be preserved as a monument of antiquity.

0 notes

Text

New Post has been published on

Indeed any ancient temple

But it is not the Pantheon, nor indeed any ancient temple, which served as the original type for the Gothic churches of Europe down to the ascendency of the Petrine type at the end of the sixteenth century. Nothing in the history of architecture is better established than the evolution of the Gothic Cathedral out of the civil basilicas of the ancient world. The whole course of that evolution can be traced step by step at Rome, in Santa Maria Maggiore, St. Paul’s without the walls, St. John Lateran, St. Clement’s, St. Agnes’, St. Lawrence, and the older churches of the basilican type. Thus with the basilicas, extant, converted, or recently destroyed, as the matrix of the Gothic churches from the fifth to the fifteenth centuries, and the Pantheon as the matrix of the neo-classical churches from the fifteenth to the nineteenth century, we feel ourselves at Rome in the head-waters from which we can trace the flow of all modern architecture.

If the Pantheon be historically the central building in Rome, it is by no means amongst the oldest monuments. Nor are the walls of Roma quadrata, nor the first structures of the Palatine. The Egyptian obelisks carry us back to a time almost as remote from the Pantheon as the Pantheon is from us. The oldest, perhaps, date from the Pharaohs who built the Pyramids, and they were made to adorn the temple of the Sun on the banks of the Nile, thence were brought by the first Caesars to adorn a circus, or to give majesty to a mausoleum, then thrown down and cast aside in Christian ages as monuments of heathendom and savage shows. Again they were restored in the classical revival after a thousand years of neglect, and set up to witness to the pride of popes and adorn the capital of Christendom mystical bulgaria tours.

Vast monoliths

What an epitome of human history in those vast monoliths, the largest of which is thirty-six feet higher than Cleopatra’s needle on the Thames, and is more than three times its weight; for a thousand years witnessing the pro-cessions of Egyptian festivals, then for some centuries wit-nesses of the spectacles and luxury of the Imperial city, then for a thousand years cast down into the dust, but too vast to be destroyed, and then set up again, with the blessings of popes and the ceremonies of the Church, crowned with the symbol of the Cross, to witness to the grandeur of the successor of St. Peter. They have looked down — these eternal stones — on Moses and Aaron, on Pharaohs and Greeks and Persians, on Alexander and Julius, on Peter and Paul, on Charlemagne and Dante, on Michael Angelo and Raphael. These stones were venerable objects before history began; they have been objects of wonder to the three great religions, three races, and three epochs of civilisation.

One can forgive destructive municipalism much for at last rescuing from ignoble uses the burial-places of the Caesars. There are no edifices in Rome more interesting to the historian than those vast mausolea — the grandest and most imposing tombs that exist—the mausoleum of Augustus, that of Hadrian, of Caecilia Metella, the Pyramid of Cestius. That of Augustus, for a hundred years the burial-place of the Caesars and their families, then a castle of the Colonnas, the scene of endless civil wars, afterwards a common theatre for open-air plays, is now at last recovered, to be preserved as a monument of antiquity.

0 notes

Photo

Indeed any ancient temple

But it is not the Pantheon, nor indeed any ancient temple, which served as the original type for the Gothic churches of Europe down to the ascendency of the Petrine type at the end of the sixteenth century. Nothing in the history of architecture is better established than the evolution of the Gothic Cathedral out of the civil basilicas of the ancient world. The whole course of that evolution can be traced step by step at Rome, in Santa Maria Maggiore, St. Paul’s without the walls, St. John Lateran, St. Clement’s, St. Agnes’, St. Lawrence, and the older churches of the basilican type. Thus with the basilicas, extant, converted, or recently destroyed, as the matrix of the Gothic churches from the fifth to the fifteenth centuries, and the Pantheon as the matrix of the neo-classical churches from the fifteenth to the nineteenth century, we feel ourselves at Rome in the head-waters from which we can trace the flow of all modern architecture.

If the Pantheon be historically the central building in Rome, it is by no means amongst the oldest monuments. Nor are the walls of Roma quadrata, nor the first structures of the Palatine. The Egyptian obelisks carry us back to a time almost as remote from the Pantheon as the Pantheon is from us. The oldest, perhaps, date from the Pharaohs who built the Pyramids, and they were made to adorn the temple of the Sun on the banks of the Nile, thence were brought by the first Caesars to adorn a circus, or to give majesty to a mausoleum, then thrown down and cast aside in Christian ages as monuments of heathendom and savage shows. Again they were restored in the classical revival after a thousand years of neglect, and set up to witness to the pride of popes and adorn the capital of Christendom mystical bulgaria tours.

Vast monoliths

What an epitome of human history in those vast monoliths, the largest of which is thirty-six feet higher than Cleopatra’s needle on the Thames, and is more than three times its weight; for a thousand years witnessing the pro-cessions of Egyptian festivals, then for some centuries wit-nesses of the spectacles and luxury of the Imperial city, then for a thousand years cast down into the dust, but too vast to be destroyed, and then set up again, with the blessings of popes and the ceremonies of the Church, crowned with the symbol of the Cross, to witness to the grandeur of the successor of St. Peter. They have looked down — these eternal stones — on Moses and Aaron, on Pharaohs and Greeks and Persians, on Alexander and Julius, on Peter and Paul, on Charlemagne and Dante, on Michael Angelo and Raphael. These stones were venerable objects before history began; they have been objects of wonder to the three great religions, three races, and three epochs of civilisation.

One can forgive destructive municipalism much for at last rescuing from ignoble uses the burial-places of the Caesars. There are no edifices in Rome more interesting to the historian than those vast mausolea — the grandest and most imposing tombs that exist—the mausoleum of Augustus, that of Hadrian, of Caecilia Metella, the Pyramid of Cestius. That of Augustus, for a hundred years the burial-place of the Caesars and their families, then a castle of the Colonnas, the scene of endless civil wars, afterwards a common theatre for open-air plays, is now at last recovered, to be preserved as a monument of antiquity.

0 notes

Photo

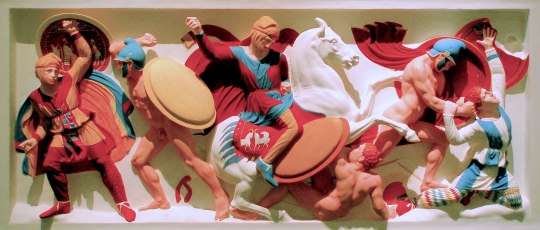

Alexander Sarcophagus, Istanbul Archaeological Museums

About this time he had the sarcophagus and body of Alexander the Great brought forth from its shrine, and after gazing on it, showed his respect by placing upon it a golden crown and strewing it with flowers; and being then asked whether he wished to see the tomb of the Ptolemies as well, he replied, "My wish was to see a king, not corpses."

…

In passports, dispatches, and private letters he used as his seal at first a sphinx, later an image of Alexander the Great, and finally his own, carved by the hand of Dioscurides; and this his successors continued to use as their seal. He always attached to all letters the exact hour, not only of the day, but even of the night, to indicate precisely when they were written.

—Suetonius, Life of Augustus

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Indeed any ancient temple

But it is not the Pantheon, nor indeed any ancient temple, which served as the original type for the Gothic churches of Europe down to the ascendency of the Petrine type at the end of the sixteenth century. Nothing in the history of architecture is better established than the evolution of the Gothic Cathedral out of the civil basilicas of the ancient world. The whole course of that evolution can be traced step by step at Rome, in Santa Maria Maggiore, St. Paul’s without the walls, St. John Lateran, St. Clement’s, St. Agnes’, St. Lawrence, and the older churches of the basilican type. Thus with the basilicas, extant, converted, or recently destroyed, as the matrix of the Gothic churches from the fifth to the fifteenth centuries, and the Pantheon as the matrix of the neo-classical churches from the fifteenth to the nineteenth century, we feel ourselves at Rome in the head-waters from which we can trace the flow of all modern architecture.

If the Pantheon be historically the central building in Rome, it is by no means amongst the oldest monuments. Nor are the walls of Roma quadrata, nor the first structures of the Palatine. The Egyptian obelisks carry us back to a time almost as remote from the Pantheon as the Pantheon is from us. The oldest, perhaps, date from the Pharaohs who built the Pyramids, and they were made to adorn the temple of the Sun on the banks of the Nile, thence were brought by the first Caesars to adorn a circus, or to give majesty to a mausoleum, then thrown down and cast aside in Christian ages as monuments of heathendom and savage shows. Again they were restored in the classical revival after a thousand years of neglect, and set up to witness to the pride of popes and adorn the capital of Christendom mystical bulgaria tours.

Vast monoliths

What an epitome of human history in those vast monoliths, the largest of which is thirty-six feet higher than Cleopatra’s needle on the Thames, and is more than three times its weight; for a thousand years witnessing the pro-cessions of Egyptian festivals, then for some centuries wit-nesses of the spectacles and luxury of the Imperial city, then for a thousand years cast down into the dust, but too vast to be destroyed, and then set up again, with the blessings of popes and the ceremonies of the Church, crowned with the symbol of the Cross, to witness to the grandeur of the successor of St. Peter. They have looked down — these eternal stones — on Moses and Aaron, on Pharaohs and Greeks and Persians, on Alexander and Julius, on Peter and Paul, on Charlemagne and Dante, on Michael Angelo and Raphael. These stones were venerable objects before history began; they have been objects of wonder to the three great religions, three races, and three epochs of civilisation.

One can forgive destructive municipalism much for at last rescuing from ignoble uses the burial-places of the Caesars. There are no edifices in Rome more interesting to the historian than those vast mausolea — the grandest and most imposing tombs that exist—the mausoleum of Augustus, that of Hadrian, of Caecilia Metella, the Pyramid of Cestius. That of Augustus, for a hundred years the burial-place of the Caesars and their families, then a castle of the Colonnas, the scene of endless civil wars, afterwards a common theatre for open-air plays, is now at last recovered, to be preserved as a monument of antiquity.

0 notes