#battle of Worcester

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The Battle of Worcester, 3rd September 1651: ‘say you have been at Worcester, where England’s sorrows began, and where happily they are ended.’

The “Crowning Mercy” and the end of the Civil Wars

Source: The Douglas Archives website

THE BATTLE of Dunbar shattered the fragile unity of the alliance gathered around Charles II to restore the Stuarts to the throne of England. The King was rapidly wearying of the dour Puritanism of the Covenanters and the constant lecturing he was receiving from Presbyterian ministers, suspicious of the sincerity of Charles’ conversion to the Calvinist cause. The “Kirk Party” (the old Covenanters who had reclaimed the government of Scotland after the failure of the Engager faction in the second civil war) began to lose ground. Charles was said to have been secretly delighted at the Kirk’s defeat at Dunbar, and looked to the rise of an authentic Scottish Royalism to propel him to his lost throne. His greatest hope was that the Catholic and pro-Suart Highlanders would come to his aid and he fled Edinburgh for Perth in October 1650, only to fall back into the hands of Covenanter forces as the promised Highland rebellion fizzled out.

At this point, the Presbyterian unity was also broken by the formation of a new military group known as the Western Association, based in the south-west of the country and under the command of a number of Covenanter officers. Their view was that the priority now was to defend the Solemn League and Covenant against the victorious Commonwealth forces, and that Charles Stuart should look to his own devices. On 2nd October the Western Association issued a ‘remonstrance’ to the Committee of Estates that blamed the defeat at Dunbar on the Kirk Party’s flawed strategy of supporting a King who continued to be surrounded by Anglican Royalists and whose personal conversion to Presbyterianism was skin-deep at best. A second remonstrance was released in which the Western Association effectively seceded from the Covenanter army, refusing to have any truck with the attempt to restore Charles to his throne. This resulted in a fundamental breach in the Scottish government in which the new faction, known as the “Remonstrants” was ranged against the Kirk Party.

With an English army dominant in Scotland and now the Covenanter government itself riven, Charles unexpectedly found himself in the welcome position of becoming the focal point of Scottish resistance against the invaders. Although most Scottish people entertained suspicion of Charles’ motivations and sincerity, they nonetheless recognised him as their sovereign, around whom they could rally to eject the hated English schematics of the New Model Army. Charles became head of an organic national Royalism that could yet transform his fortunes. The Kirk Party therefore determined to work with the Royalists to bring the Remonstrants to heel, but before they could, Cromwell and Major-General John Lambert did their work for them. The Western Association army was commanded by Colonel Gilbert Ker, who becoming aware of the Kirk’s intent to force the Remonstrants into compliance, thought his best option was to gain credibility and renown for his faction by defeating the English. Cromwell meanwhile had already decided to destroy Ker’s small army before moving on to contend with the Committee of Estates’ remaining forces under David Leslie. Initially Ker met with success, stymying Cromwell at the Clyde in late November and then moving to meet Lambert’s troops, whom he believed he outnumbered, outside Hamilton. On 1st December Ker entered the town believing Lambert’s troops had withdrawn, only to be ambushed by the Commonwealth forces as he did so. In the following short sharp battle, the Western Association army was destroyed.

The decisive defeat of the Remonstrants, although welcomed by the Committee, also deprived it of an army it had hoped to bring back into the fold. The government therefore quickly renounced previous strictures that had prevented Royalists, Anglicans, former Engagers and other “schematics” from forming armed forces. With the reluctant acquiescence of the Presbyterian ministers, the Kirk Party was able to increase its military strength to twenty five regiments by creating what was a genuinely Scottish national army, named the Army of the Kingdom. This paved the way for the formal coronation of Charles as King of Scotland at Scone, near Perth on New Year’s Day 1651. Charles was crowned by Archibald Campbell, Earl of Argyll, head of the Scottish government and now, at the apex of his power, kingmaker too.

However, despite the new optimism brought about by this display of national unity, what should happen next was not at all clear. Cromwell controlled the capital and all routes into England; Charles’ natural heartland of the Highlands was cut off from him and although Leslie had adopted a strong defensive line across the Firth of Forth, there was no immediately obvious military strategy that could feasibly deliver victory. Winter became spring which became summer with no movement by either side until Cromwell at last resolved to force the issue. In mid-July he ordered an amphibious crossing over the Forth, using flat-bottomed boats, and Commonwealth troops were soon landed on the Fife shore under the command of Lambert. The Scots moved to repulse the English force but Leslie’s soldiers were raw recruits who, in open battle, were no match for Lambert’s ironsides. The two armies met on the hills outside the town of Inverkeithing and it took just fifteen minutes for the experienced New Model troops to scatter their opponents. Over 2,000 Scots were killed in the ensuing rout, 1500 men were taken prisoner and the defensive front around Fife collapsed. There was now only one option left open to Charles and Leslie: to launch an invasion of England.

The evidence is that this is precisely what Cromwell wanted Charles and the Scots to do, because he removed his own forces from the roads into England and proceeded to attack and capture Perth. It is likely that the King and Leslie knew that they were heading into a trap, but Charles continued to entertain the hope that once the Royal standards were sighted in England, Royalists would rally to his cause and the relatively small army of 12,000 that commenced the march south on 31st July, would soon grow to become a force equal to those that could be fielded by the Commonwealth south of the border.

The Scots army crossed into England on 6th August. Charles’ high spirits did not last long. Not only did Argyll refuse to join the expedition on the grounds he thought it was folly, but the hoped-for rally of English Royalists did not happen. There was an abortive attempt to join Charles by Lord Stanley from the Isle of Man but, apart from this, just 200 reluctant recruits from Manchester joined the Royalist army. In truth, the English population were tired of war. They had no real love for the Puritan Commonwealth, but at least the New Model Army could enforce peace and slowly, over the last two years, life had begun to return to some sort of normality. Furthermore, there was no affection for the Scots who made up most of Charles’ army, either. This was the fourth Scottish invasion of England in twelve years and the destruction and plunder that had accompanied previous incursions had not been forgotten. Meanwhile, leaving George Monck to continue to hold Commonwealth positions in Scotland, Cromwell led an infantry-based force in pursuit, while Lambert and Colonel Thomas Harrison followed Charles at the head of two small cavalry forces, harrying his troops all the way. Finally, on 31st August, the Royalists arrived at Worcester, where Leslie determined the decisive battle needed to be fought.

Worcester did make sense as a base of operations from a Royalist perspective: the city had historically supported the King; it was bounded by the River Severn and was close enough to the Royalist heartlands of Cornwall and Wales. It was also defensible with a number of bridges into the city which could be destroyed or be blocked and it was partially walled. However, as the Royalists settled into their new stronghold, they were effectively surrounded. Cromwell, Harrison and Lambert had combined their forces and, supplemented by local Parliamentary levies, the Commonwealth army now numbered 31,000 men, significantly outnumbering Charles’ force. On 3rd September, Cromwell ordered an assault from the south, under Lambert, who built pontoon bridges to cross the Severn with 11,000 troops, while Cromwell himself positioned artillery to the east of the city and commenced a bombardment. Lambert’s troops encountered stiff resistance as they tried to cross the River Teme at Powick Bridge (ironically the site of the first skirmish of the first civil war) necessitating Cromwell to lead reinforcements to force the crossing. This in itself left the Commonwealth eastern flank exposed enabling Charles himself to lead a mounted charge out of the city that nearly broke the extended Parliamentary line. Fighting uphill, the Royalists were unable to pursue their advantage and when Cromwell’s troops returned, Charles was forced to retreat back into the town. Meanwhile Lambert had defeated the Scots facing him and the battle degenerated into a vicious street by street struggle. This ended when Cromwell captured Fort Royal and turned the city’s guns onto the Scots. The stubborn Royalist retreat became a rout with soldiers fleeing the city best they could.

The Royalist army was almost completely destroyed. 3,000 men were killed and 10,000 were captured, including Leslie and all his senior officers. Charles himself miraculously managed to escape and spent six weeks on the run, hunted by Roundhead troops and helped by a network of mainly Roman Catholic aristocratic safe houses. He almost certainly did seek refuge for at least one night in the oak tree at Boscobel while Parliamentary soldiers searched for him underneath its branches. Charles eventually managed to escape to France on 16th October. While he remained alive, the dream of the restoration of the monarchy remained intact, but in all practical terms, the Royalist cause was dead.

Cromwell himself knew that the nine year English civil war was indeed over. In his despatch to the Council of State, describing his final military victory in the Parliamentary cause, he summed up the country’s prevalent feelings of relief as much as triumph at the outcome of the battle, when he described Worcester thus: ‘It is, for aught I know, a crowning mercy.’

#english civil war#oliver cromwell#charles ii of england#David Leslie#battle of Worcester#John lambert#Thomas Harrison

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Percies' strategy was a combination of audacious extemporisation and sound military judgment. Its failure was due primarily to the fact that it was based on the apparently accurate premise that it took cognisance of all the men assembled in arms in England and Wales in the first half of July 1403. From as early as the first days of Hotspur's recruiting campaign in Cheshire, however, there was an unforeseen factor the army of the king himself and for this crucial flaw in their scheme, the Percies had only themselves to blame. The earliest evidence that this army was on the move is Henry's letter from Higham Ferrers, in Northamptonshire, dated 10 July, informing his councillors that he was proceeding north to assist the Percies before embarking on an expedition against the Welsh. As this force was obviously mustered before Hotspur's arrival in Cheshire, and as the latter seems to have taken the prince by surprise after more than a week's recruiting within forty or fifty miles of Shrewsbury, it seems highly improbable that Henry knew anything of the insurrection by that date. It is far more likely that his explanation was at least broadly genuine, and that his main concern was the security of the Scottish border. If, as has been suggested, the Percies' actions had precipitated a real risk of invasion, there was good cause for the king to intervene or at least investigate, whatever his attitude towards the Percies and their attempts at self-aggrandizement.

Peter McNiven, "The Scottish Policy of the Percies", Bulletin of the John Rylands Library, vol. 62, no. 2 (1980)

#henry hotspur percy#henry percy 1st earl of northumberland#henry iv#henry v#thomas percy 1st earl of worcester#historian: peter mcniven#the battle of shrewsbury#the percy rebellion#percies

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

i am suddenly filled with the desire to name an oc worcester

#watching a video abt werster's battle frontier all gold medal speedrun#and i keep thinking the commenter is trying to say worcester#shut up alex

1 note

·

View note

Text

On June 30th 1685, the 9th Earl of Argyll went the same way as aul man, the 8th earl, when he was executed in Edinburgh.

This post ties in with a few others, the first just a couple of days ago, the execution of Richard Rumbold, who joined Archibald Campbell, the 9th Earl in what is known as The Argyll Rising, an attempt to dethrone King James VII.

The English know this as the Monmouth Uprising, for reasons that will become apparent, this was naked attempt to overthrow the incumbent of the throne, James VII & II, and place the Duke of Monmouth, Charles II’s illegitimate offspring, there in his place.

Much has been written of Monmouth’s part of the rebellion but there is comparatively little commentary on Argyll’s efforts with the Scottish aspect of the rebellion.

Monmouth, having landed at Lyme Regis in June 1685 with less than 100 men, was quickly reinforced by local volunteers to the tune of 1000 troops. Over the next 4 weeks his army fought a serious of indecisive skirmishes against royalist troops before he was brought to a definitive set-piece battle at Sedgemoor a month after landing where his poorly trained and disorganised force was utterly routed by the regulars of the King’army. Monmouth was duly executed for high treason.

If Monmouth’s end of the rebellion was comical, Argyll’s efforts north of the border degenerated swiftly to the farcical. Arriving in Orkney a month before Monmouth docked at Lyme Regis, Archibald spent 4 weeks sailing around the west coast attempting to round up supporters for his cause. Bedevilled by lack of support and mutiny amongst those who did rally to his colours, he finally found himself at Dumbarton with only his son and 3 friends by his side. Subsequently captured by Government troops Argyll was executed in Edinburgh a week before Monmouth met his end.

This Archibald, the 9th Earl, features in the Claverhouse story as much as Oor Archibald, the 10th Earl. To his credit he fought for his king and Scotland against the depredations of Cromwell and took part in both military disasters of the Battle of Dunbar in 1650 and then the Battle of Worcester the following year. He survived through the interregnum, keeping one foot on both Stuart and Cromwellian camps, trusted by neither and viewed with high suspicion by both. And his father, Archibald the 8th Earl was executed on Charles II command in the immediate aftermath of the restoration in 1660.

In the complicated political atmosphere post the Restoration, Archibald the 9th Earl, sought to navigate the difficult waters but was confounded by the passing of the Test Act in 1681. This required all the nobility to take an oath which required a profession of the Protestant religion AND an affirmation of royal supremacy in all matters spiritual and temporal, aye it’s that old divine right again.

This created too much of a compromise for Archibald who refused to take the oath and was, consequently, tried before his peers in December 1681, with one John Graham of Claverhouse present on the jury, he was sentenced to death. But prior to his execution he managed to escape from Edinburgh Castle, in disguise, and abetted by his step daughter Lady Sophie Lindsay. He was eventually executed, as outlined above, following the failure of Monmouth’s Rebellion.

This snippet describing his demise is fro Edinburgh Old And New…..

At noon on the 30th June, 1685, he was escorted to the market cross to be “beheaded and have his head affixed to the Tolbooth on a high pin of iron.” When he saw the old Scottish guillotine, under the terrible square knife of which his father, and so many since the days of Morton, had perished, he saluted it with his lips, saying, “It is the sweetest maiden I have ever kissed.” “My lord dies a Protestant!” Cried a clergyman aloud to the assembled thousands. “Yes,” said the Earl, stepping forward, “and not only a Protestant, but with a heart-hatred of Popery, Prelacy, and all superstition.” He made a brief address to the people, laid his head between the grooves of the guillotine, and died with equal courage and composure. His head was placed on the Tolbooth gable, and his body was ultimately sent to the burial-place of his family, Kilmun, on the shore of the Holy Loch in Argyle.

The second pic is called The last sleep of Argyll, and depicts him the night before he got the chop.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Photo: Statue of Aethelflaed, Lady of the Mercians, who passed away in 918. Her nephew Aethelstan, future king of all England, looks up at her.

"Aethelflaed was one of three daughters of Alfred the Great, and her name meant "noble beauty". She married Aethelraed of Mercia at some point during the 880s and while this union meant a strong alliance between Wessex and Mercia the pair embarked on a "Mercian revival" with the city of Worcester at its centre.

When Aethelraed died in 911 after years of ill-health Aethelflaed remained as Lady of Mercia and held this position until her death, making her the only female ruler of a kingdom during the entire Anglo-Saxon era. The only compromise she made was to agree to her brother Edward, now king of Wessex, taking some of Mercia's southern lands under his control.

Their father Alfred the Great had fortified dozens of Wessex towns as "burhs" and Edward continued this work, connecting his burhs with those in Mercia to represent a united front against viking incursions, and it wasn't long before this was put to the test.

A force of vikings, pushed out of Ireland, landed in the mouth of the Dee after unsuccessfully trying to take land in Wales, and asked Aethelflaed if they could settle for a time outside the old Roman walled town of Chester. Permission was granted but the Norsemen raided and robbed the area at will so Aethelflaed led a force to shut them down. She had Chester fortified and waited for the inevitable viking attack, it came and was repulsed, the Scandinavian chancers sent packing in complete disarray.

This same Norse army was brought to battle at Tettenhall near Wolverhampton where Aethelflaed's forces destroyed them. The writing was now on the wall - the vikings had to go. Together with Edward she raided deep into Danelaw territory on a mission to rescue the bones of St Oswald - who had been killed and ritually dismembered by the pagan king of Mercia Penda - from a church in Lincolnshire then brought the relics down to Gloucestershire where a new church was built to house them...more on that presently.

The burhs continued to be built, and the Dane strongholds fell as Aethelflaed campaigned hard against them. Her forces defeated three Norse armies before finally taking the city of Derby, then Leicester, before the Danes of York came to her to pledge their loyalty. The vikings in Anglia capitulated to Edward and so all of England south of Northumbria was now back under Anglo-Saxon rule.

Aethelflaed died at Tamworth in 918 and so will be forever associated with the town, but she was carried down to Gloucestershire to be buried in the church she had built for St Oswald. Unfortunately the monastery there fell into decline over the centuries, was dissolved in 1536, then almost completely destroyed during the English Civil War. Nobody knows where Aethelflaed's resting place is now, but the ruins of St Oswalds are as good a place as any as a pilgrimage destination for those wishing to follow in the footsteps of the Lady of Mercia." - Source: Hugh Williams via Medieval England on FB.

Photo: Statue of Aethelflaed and Aethelstan at Tamworth Castle, by EG Bramwell, unveiled in 1913.

#Aethelflaed#Lady of the Mercians#Aethelstan#Aethelraed of Mercia#Medieval History#Alfred the Great#Wessex#Mercia#Northrumbria#England#Anglo-Saxon#Tamworth Castle#Statue#Medieval England#Hugh Williams

67 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Minstrel, the Maiden, and the Knights of Hellfire - Chapter 8

Pairing: Hellcheer, Medieval AU

Summary: England, 1139: the civil war between King Stephen and Empress Maud looms large, threatening to tear the country in half. For Ed and his band of traveling minstrels, however, the more pressing matter is how to survive the upcoming winter, now that they were tossed out by their latest patron. When they stumble upon a naïve pageboy looking for warriors to escort the lady Christiana to safe haven in Wales, Ed comes up with a daring plan - pose as knights, take the job, and collect the reward. After all, how hard can it be? What Ed doesn't count on is endless battles, treacherous roads, marauding bandits, Lady Christiana's pompous fiancé, and his own growing attraction to the fair maiden herself...

Chapter warning: some violence

Chapter word count: 3.5k

Chapter 1 - Chapter 2 - Chapter 3 - Chapter 4 - Chapter 5 - Chapter 6 - Chapter 7

Chapter 8

They got as far as Stratford, a small village upon the River Avon, when they heard the news that Stephen had had to give up his western campaign and was now returning east to protect the capital from the forces of Miles of Gloucester, who had transferred his liege to the Empress. This had no effect on the company, save for allowing them a collective sigh of relief. What care had they for who was fighting who, as long as the road was safe again? Abandoning their flight to the north, they turned west once more, following the Avon until it met the Severn, whence they would cross Worcestershire and Herefordshire into Wales.

This was Ed's country. He'd grown up in a village nestled between two ranges of hills, the Clee and the Malvern, which embraced the valley like a pair of lovers' arms. The closer they got to Worcester, the more it felt like homecoming to him, though perhaps an uneasy one. He tried to tell himself that the last time he walked these roads had been nearly twelve years ago, a frightened child, unwanted, lost. Anyone who had known him back then would not recognize him now.

They still performed at every stop along the way. The only difference was that Christiana now joined them for every performance, heralded by Geoff, who was their master of ceremonies, as the Dancing Princess. Christiana accepted the moniker with good cheer and eagerly took to the stage, where her dances were always received with great enthusiasm and largesse. The tension they'd felt in Campden had seeped through the Midlands. There were talks that the attacks in the east were just a ruse to lure King Stephen away, and now the Empress was moving her forces into the unguarded territory in the west to take it for herself. The entire region seemed poised on a precipice, awaiting the terrible fall. In the meantime, the people still had to eat and drink and find ways to divert themselves, and Christiana's presence, her smile, and the way she moved, ethereal yet still utterly vivid and alive, could always calm them down and help them forget their troubles, even for a little while.

Finally, the River Severn was within sight, coiling under the November sky like a ribbon of molten silver, and with it, rose the roofs and steeples of the town of Worcester. From there, it was only forty miles to Offa's Dyke on the Welsh border, and then thirty miles more to Llandovery, and their journey would come to an end. Ed tried not to think of it, but sometimes, watching Christiana dance to his music in the fitful torchlight of the tavern, seeing her smile and her eyes fixed on him, he would hope, against all senses, against all reasons, for a miracle to keep them together. He kept telling himself that Fate couldn't have conspired to bring them back together, only to tear them apart again. After all, stranger things had happened, hadn't they?

But all was not right with Worcester. Even before they came to its gate, they had seen columns of dark, greasy smoke from behind the town walls and heard its bells—not the calm, stately bells to sound the Divine Offices, but the frantic bells to signal alarm. And, underneath the anxious tolling of the bells, there was screaming. The thin, frightened screams of women and children, and the menacing, bloodthirsty screams of men.

"Something's happening..." said Dustin fearfully as they drew to a stop on the road, watching the town in the distance, too afraid to take another step.

While they lingered, the town gate burst open, and people poured out of it, men, women, and children, laden down with their earthly possessions. Some were shot down by archers atop the town walls, others were ridden down by mounted soldiers and dragged back into town screaming. Fortunately, the soldiers seemed half-hearted in their chase, and, as more and more refugees fled from the burning town, the soldiers soon gave up the hunt to pursue more lucrative looting within the walls of the town itself. Those fortunate few who escaped were scattered in all directions, like fallen leaves blown by the cruel winter wind.

Soon enough, some of these wretched people came to the main road, where the minstrels still stood transfixed by fear and indecision, caught in a flood of panicked humanity. Ed managed to grab one of them, an old man whose back was bent under a heavy scrip, leg limping from a wound—new or old, it was impossible to tell.

"What's happened?" Ed asked.

"A siege!" the old man panted, trying to squirm out of Ed's grasp. "Gloucester—his entire army—burning, killing, taking everything and everyone—get away while you can—" He pulled his cloak free and limped away without a look back.

Ed turned around and saw six pairs of panic-stricken eyes looking back at him. He could feel his own panic rising, cold and bitter like bile at the back of his throat, numbing his limbs. All the detours, all the roundabout ways taken to avoid the fighting, wasted. They all looked to him for protection and guidance, and he had led them straight into a battle. The panic reached his head, muddling his thoughts, so he could no longer see a way out.

Christiana pushed her way to the front and took his hand. "What do we do, Ed?" she asked.

At the sound of her voice and the feel of her hand in his, some of the fog lifted from Ed's mind. He couldn't afford to lose his head now. They were depending on him. She was depending on him.

"We take the back roads," he said, a plan forming in his mind. "The soldiers are busy securing the town right now, but once it falls, they will turn their eyes to the countryside. Though we don't have much that they'd want to take"—here Ed noticed that Christiana exchanged a meaningful look with Dustin and Maxime, but there was no time to press for an explanation—"I'd rather not take any chance."

"Wait," said Dustin. "If this is the Empress's force attacking, why do we have to run? If they know my lady is loyal to the Empress, surely they will spare us and let us through—"

Before the boy could finish, the others all raised their voices to drown him out.

"Have you lost your wits?" said Gareth.

"What do you suggest, that we offer Lady Christiana up like a sacrificial lamb so we can have safe passage?" said Maxime contemptuously.

Even Christiana shook her head at him. "We cannot risk it, Dustin," she said. "These soldiers do not care where our loyalty lies; all they care is whether we, or our friends and families, have enough coin to ransom us. We must avoid them at all costs."

His face turning crimson, Dustin sheepishly fell back. Ed nodded at Tadhg, who took Warlock's bridle and turned the wagon off the main road, toward the line of trees on their left. Wordlessly, the others followed.

Once they were behind the cover of the trees, Tadhg drew Warlock to a halt. "We can't go in there, Ed," he said, pointing to the woods beyond, where the trees grew so thick together that the place was shrouded in shadows despite the leafless branches. "The wagon won't fit."

It was true. Ed looked around, pondering. His eyes landed on a large thicket of brambles, almost as tall as he was. The berries were long gone, but the leaves, though browned and withered, remained, and the thorns were sharp and plentiful enough to deter any busybody.

"There," he said. "We hide the wagon. Anything you don't want to lose, take it with you. We can come back for it after, or..." He swallowed and squared his shoulders in an attempt to look brave. "... or we can replace it, if need be."

He helped Tadhg unhitch Warlock from the wagon while the others took their things out of it. Ed and his friends had few possessions except for their instruments and some clothes, which they put in a bundle on Warlock's back. The costumes and props they left behind, though Ed took the swords with them. Fake they may be, but these swords would make decent singlesticks, and they needed all the weapons they could get. They had eaten most of their store of food, and Tadhg distributed the remaining bread and cheese and ale amongst them. Dustin, Maxime, and Christiana took their saddlebags and scrip.

Ed noticed Christiana's hands shook as she fixed the scrip's strap over her shoulder, so he gave her fingers a squeeze. "Everything will be all right," he told her, with an air of reassurance he didn't feel.

She nodded silently at him, her eyes wide on her pale face. Then, opening the scrip, she took her coin pouch and counted out forty shillings, which she handed to Ed and his friends. "I know we haven't reached our destination yet," she said, "but please accept this, in case—in case we get separated, or—"

"No!" Ed pushed the coins back toward her. "We take the payment once we've seen you safely to Wales, and not before. We stay together. Everything will be fine."

Christiana shook her head. "Please, take it," she insisted. "For my peace of mind."

Reluctantly, they took ten shillings each. Then, half dragging, half pushing, they put the wagon as deep inside the brambles as they could, covering it with dead branches and dry leaves. This done, they walked westward through the woods, pulling Warlock along.

"If we do get separated," Ed said to his friends in a low voice so Christiana couldn't hear, "make your way to my uncle's croft. And try to keep one of them with you." He nodded at Dustin and Maxime, who were clutching their bags white-knuckled as they stumbled through the trees. Christiana he didn't have to worry about keeping close, for she hadn't let go of his hand save for a brief moment to unload and help to hide the wagon.

Geoff, Gareth, and Tadhg nodded back solemnly.

For all of Ed's attempts at bravery, he couldn't stop fear from forming in the pit of his stomach, cold and heavy like a ball of ice. The wagon had been their home for so long that he felt exposed without it. And although they were further and further away from Worcester, the sound of fighting and the acrid smell of smoke still wafted toward them through the cold, still air, a quiet threat that urged them to hasten their steps and put more distance between them and the battle. Christiana's act of distributing the coins had an air of finality about it, as though they were already being separated, and also served as a reminder of the danger they were in.

They continued their way westward, keeping the burning town behind them. A movement from behind the trees made Ed reach for his wooden sword and Maxime for her dagger, but it turned out to be just a woman, with two little boys in tow. They stared at Ed and his company in mute apprehension, and, apparently deciding that they were safe, fell in steps alongside them, just as silently. More travelers appeared from further down the woods and other winding footpaths and joined them as well. Unlike the desperate refugees from the town, who had only been focused on getting as far away as quickly as possible, these people had a stealthy, wary look about them, as though they had been on the road for a long time and were treading with the utmost care, lest they drew attention to themselves and brought the attacking force down upon them all. Ed guessed they were the ones who had left town early in anticipation of the siege.

It seemed a perverse imitation of their first day on the road—now, as had then, they were traveling in a large group, except instead of being accompanied by bright blue skies, warm sunshine, and cheerful music, they walked under the November sky, heavy with lead-colored clouds, and in an oppressive silence only broken by the sound of shuffling feet and the occasional whimper from a child. No one talked or even looked at each other.

The travelers didn't rest or share their food; those who did have food ate when they could without stopping. One of the boys, the older one, was clearly hungry—he was dragging his feet, and his stomach gurgled so loudly that they could all hear it. Christiana offered a piece of bread to him, but he turned away and hid his face in his mother's skirts.

"You should eat something," Christiana said. "So you can keep your strength for your mother and brother—"

"We don't need your charity!" the mother snapped, pushing the bread away.

"Forgive me," Christiana said. "I didn't mean..." Her voice trailed off, and she looked close to tears. Ed glared at the mother as he drew Christiana to him, patting her arm in a clumsy attempt at comfort.

The sound of water murmuring ahead signaled the approach of a stream. Their path started to slope downward and narrow into a bottleneck pass, forcing the travelers to walk only two abreast while holding on to tree trunks and branches to keep their balance. Tadhg, his hands full with Warlock's bridle, fell to the rear of the cortege.

Ed did not like the look of the pass. There was nowhere for them to run should they be ambushed—trees grew close on either side of the path, hemming them in, and ahead, at the bottom of the slope, was a large, swampy brook. He wanted to suggest turning back, but the people around him were so grim-faced that his words died in his throat. Well, perhaps if they hurry and cross the brook, it would be safer...

The woods around them exploded.

Men, dozens of them, dressed in faded homespun so they blended in almost perfectly with the brown and dead trees, came at the travelers from all sides. A child screamed. Warlock whinnied loudly. Ed's knees went weak. These were no Alf and his cronies, no erstwhile crofters and serfs driven off their land and forced to become outlaws. Despite their rough attire, these men were fully armed, with chainmail or leather armor over their homespun, and had the hardened look of career soldiers, those who delighted in robbing and pillaging as much as they did in fighting. Their tattered garments appeared to be for disguise rather than due to necessity, and their weapons gleamed as they were swung at the travelers. Some travelers tried to fight back with their knives and staves, but they were no match for these men. More screams went up as several of the party fell under swords and arrows, and soon the soldiers had them surrounded.

"P-please," the woman walking next to Christiana begged, clutching her two boys close. "Please don't hurt us. We have nothing..."

"Nothing, eh?" the leader of the soldiers said. His face was a mass of scars, out of which his black eyes shone like two embers as they roamed over each traveler, appraising, weighing, measuring. "We'll see about that. Take that horse," he nodded at Warlock, "and search them for valuables. Carefully."

Christiana squeezed Ed's hand so hard he was afraid she might crack the bones.

One of the soldiers was moving toward Tadhg and Warlock. They didn't have much time left. There was no telling what these soldiers would do to them—they would be taken for ransom, or worse. All Ed knew was that he would be damned if he let anything happen to Christiana.

He counted the soldiers. He counted their own numbers. An idea occurred to him.

"Geoff," he said, out of the corner of his mouth. "The Battle of Hastings."

Geoff frowned at him in confusion.

"When the Normans feinted retreat to trick the English into breaking ranks, remember?" Ed whispered. The Battle of Hastings wasn't their forte—they were much better versed in the Crusade—but they had reenacted it a few times, and Ed trusted his troupe to remember the movements.

Geoff nodded, finally understanding. Ed inclined his head toward the three archers. They were the biggest threat and had to be taken out first. Geoff gave Gareth, who was on his other side, a small nudge and whispered the plan to him. Tadhg was too far away, but once the signal went up, he would know what to do. As for the others... Ed could only pray that their wits were quick enough, and so were their legs.

Ed turned to Christiana. "Whatever happens, stay close to me," he said under his breath. Her eyes widened slightly, but when he pressed her hand in reassurance, she pressed back, showing that she'd understood.

Taking a deep breath, Ed bellowed, "A white dragon! Saint George for merry England!"

Never mind that it was the war cry of the Saxons, and they were playing the part of the Normans in this particular act. The cry had the intended effect. The soldiers jumped like startled rabbits, temporarily stunned into confusion, not knowing where the cry had come from. Tadhg, bless him, immediately knew what it meant. He let go of Warlock's bridle. The horse reared up with a half-frightened, half-triumphant whicker, front legs coming down on the approaching soldier. The soldier fell back. Several of his comrades ran over to capture the horse, but Warlock broke through their ranks and disappeared into the woods.

Good luck, old friend, Ed thought. He prayed that he would find Warlock again, and if not, that the horse would be safe wherever he ran to.

While the soldiers were still in confusion after Warlock's flight, Ed and his friends rushed at the archers, bowled them over, and wrestled the bows out of their hands. Maxime's dagger bloodied a couple of the soldiers, and Geoff's wooden sword connected with a few heads and necks. The rest of the party descended into chaos, which was exactly what Ed wanted.

"Run!" he screamed at his fellow travelers. "Run in circles! Confuse them!"

He didn't know if they understood him or not, but run they did, some down the slope and across the brook, splattering mud and water, others back the way they came. The soldiers cursed, uncertain as to which they should follow. One of the archers regained his bow, but the circuitous paths the travelers were taking meant that he did not have an accurate aim. Gareth, Geoff, and Tadhg were also running in the same direction as Warlock. Ed caught a glimpse of Maxime's red braid as she followed Geoff into the trees, and heard Dustin scream, "No! My lady—I cannot leave her—" while Gareth roared at him, "Run, you fool!" before they, too, disappeared.

A shriek from Christiana made Ed spin around. She was grappling with a soldier for her scrip. The soldier, clearly having no qualms about hitting a lady, pulled out his sword.

"Christiana!" Ed screamed a warning and ran toward her. In the same moment, she twisted away from the soldier, slipped on the bed of dead, moist leaves covering the path, and went tumbling down the slope.

Ed's singlestick sword slammed down on the soldier's unprotected nape, causing the man to stagger. Seizing the advantage, Ed pushed the soldier aside and ran after Christiana, heedless of the branches on either side of the path that snapped at his face and scratched his hands, stinging like horsewhips.

He came to the bottom of the slope just in time to see Christiana floundering in the middle of the brook—the momentum of her fall had propelled her straight into the water. Without taking the gittern from his back, without even stopping to think, he jumped in after her. The water was frigid, but it did little to deter him. An arrow whizzed past his ear. On top of the slope, he heard the archer let out an oath. Christiana was still thrashing and spluttering somewhere to his right, weighed down by her heavy scrip.

"Let it go!" he shouted. "Throw it away!"

"No—" Water went into her mouth, choking her, and she went under.

Biting back a curse, Ed swam to her. One, two long strokes, and he managed to grab the back of her cloak and pull her spluttering to the surface.

"Hold your breath!" he said and plunged them both under again just as another arrow flew over their heads. Emerging a few heartbeats later, he saw some soldiers clambering down the slope. A log drifted past. Ed grabbed it, pulled Christiana's arms securely around it, and, allowing her to lean on him to keep her head out of the water while he leaned on the log, he let the swift current bear them away, away from the shouting, the clanging of swords, and the hissing of arrows.

Chapter 9

#hellcheer#hellcheer fic#hellcheer au#eddie munson#chrissy cunningham#joseph quinn#eddie x chrissy#eddissy#joseph quinn fic#medieval au

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

John Leslie, 7th Earl and 1st Duke of Rothes, 1630 - 1681. Lord Chancellor

Artist: L. Schuneman German

Date: 1667

Medium: Oil on canvas

Collection: National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh, Scotland

Description

This portrait was painted in 1667, the year that Rothes became Lord Chancellor of Scotland. An unwavering supporter of Charles II, Rothes was captured by Cromwell at the battle of Worcester in 1651 and imprisoned in the Tower of London. His loyalty was rewarded on the restoration of the monarchy in 1660, after which he held a series of high offices of government. Rothes had a reputation for indulging in all the pleasures of life, including wine and women and he denied himself nothing 'that might maintain his greatness, or gratify his appetites’.

#portrait#painting#oil painting#oil on canvas#artwork#man#interior#standing#three quarter length#wig#costume#john leslie#scottish culture#lord chancellor of scotland#scottish history#l. schuneman

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

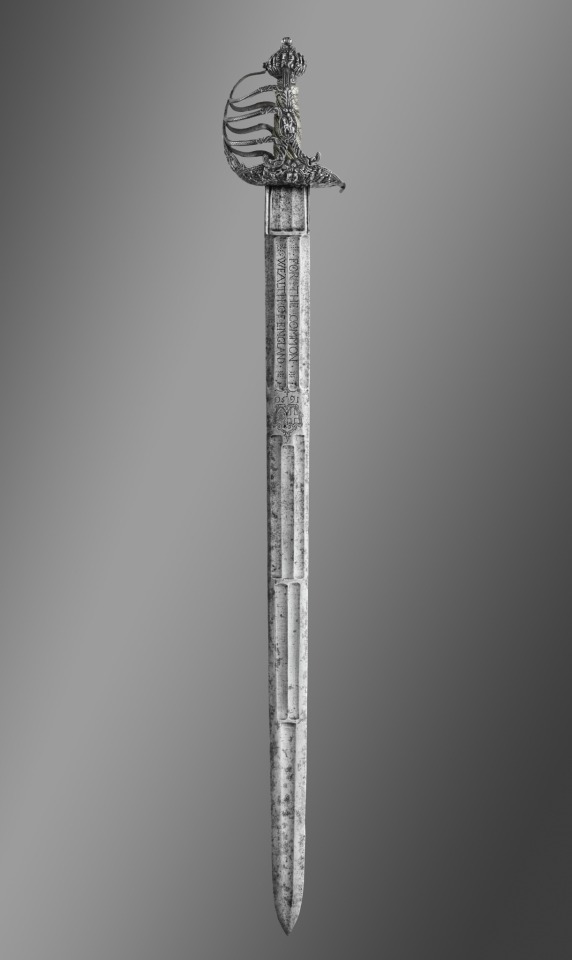

⚜️ Broadsword of Oliver Cromwell, England, c. 1650

Medium: Iron alloy (steel), partially engraved; chiseled; silver wire; wood

Length (overall): 96.8 cm

Blade: 82.6×4.9 cm

Hilt: 12.9×11.7 cm

Pommel: Height-5.4 cm, Diameter-3.3 cm

Weight: 1405 g

Facts:

▪️ August 9, 1655 - Lord Protector Oliver Cromwell divides England into 11 districts

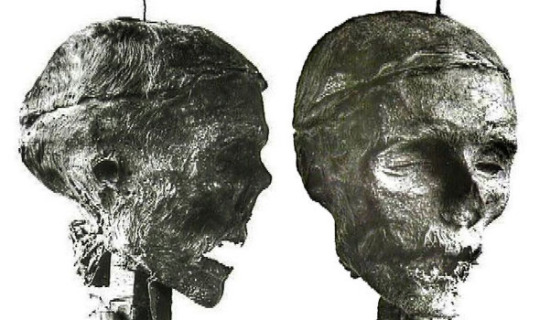

▪️ Cromwell is an iconic figure in British history

▪️ He was a key figure in the trial and execution of King Charles I

▪️ He has the peculiar distinction of being the only political criminal to be executed two years after his death

Cromwell was exhumed from his grave in 1661 and put on trial by the late king's son, Charles II. Posthumously convicted of high treason, Cromwell's corpse was hanged and beheaded, and his head was impaled on a 6-meter spike atop Westminster Hall. The mummified head remained on the spike for more than 20 years

▪️ In 1960 (300 years after Cromwell's death), Dr. Horace Wilkinson donated the head to Sidney Sussex College at Cambridge, Cromwell's alma mater

"Cromwell's head is buried somewhere in the college chapel, supposedly in a biscuit tin" (says Stuart Orme, curator of the Cromwell Museum)

▪️ Cromwell's most famous quote is "Put your trust in God, my boys, and keep your powder dry," but there's no proof that he actually said it. The line comes from a 19th-century poem called "Oliver's Advice" based on a "well-authenticated anecdote" associated with Cromwell

▪️ September 3 is a fateful date: Cromwell routed the Scots at Dunbar (1650). The Battle of Worcester would prove to be the final action of the English Civil Wars (1651). Cromwell's first Parliament met on 3rd September, 1654.

▪️ Cromwell died suddenly at age 59 on 3rd September 1658. He suffered from a lethal combination of malaria and typhoid fever.

- -

⚜️ Палаш Оливера Кромвеля, Англия, ок. 1650

Материалы: сталь, гравировка; серебряная проволока; дерево

Длина (общая): 96,8 см

Лезвие: 82,6×4,9 см

Рукоять: 12,9×11,7 см

Навершие: высота-5,4 см, диаметр-3,3 см.

Вес: 1405 г

Факты:

▪️ 9 августа 1655 г. Лорд-протектор Оливер Кромвель делит Англию на 11 округов

▪️ Оливер Кромвель - человек, повлиявший на ход истории Англии

▪️ Он был ключевой фигурой в судебном процессе и казни короля Карла I

▪️ Известен тем, что является единственным политическим преступником, казненным через 2 года после своей смерти. Был эксгумирован в 1661 г. и предан суду сыном покойного короля Карлом II. Посмертно осужденный за государственную измену, труп Кромвеля был повешен и обезглавлен, а его голова была пронзена 6-метровым штырем. Мумифицированная голова оставалась на крыше Вестминстерского дворца более 20 лет

▪️ В 1960 г. (через 300 лет после смерти Кромвеля) доктор Гораций Уилкинсон пожертвовал его голову колледжу Сидни Сассекс в Кембридже, альма-матер Кромвеля.

"Голова Кромвеля похоронена где-то в часовне колледжа, предположительно в банке из-под печенья" (Стюарт Орм, куратор музея Кромвеля)

▪️ Самая известная цитата Кромвеля: "Уповайте на Бога, мальчики мои, и держите порох сухим", но нет никаких доказательств того, что он действительно это сказал. Эта строка взята из стихотворения XIX в. под названием "Совет Оливера", основанного на "достоверном анекдоте", связанном с Кромвелем

▪️ 3 сентября - роковая дата Кромвеля. В этот день он одержал победу над шотландцами при Данбаре (1550), разгромил отряды Карла I в Вустере (1651). Первое заседание созданного Кромвелем парламента (1654), после чего этот день был объявлен Днем благодарения.

▪️ Умер 3 сентября 1658 г. в возрасте 59 лет от малярии и брюшного тифа

#кромвель #Cromwell #Broadsword #палаш #меч #вооружение #armsandarmor

#medieval#средневековье#middleages#history#история#arms and armor#broads and broadswords#broadsword#вооружение#меч#палаш#кромвель#оливер кромвель#oliver cromwell

104 notes

·

View notes

Text

King Charles II in Boscobel Wood

Artist: Isaac Fuller (English, 1606-1672)

Date: 1660's

Medium: Oil on canvas

Collection: National Portrait Gallery, London, United Kingdom

Description

The second of a set of five scenes that commemorate Charles II's dramatic escape from Parliamentarian forces following his defeat in the final battle of the civil wars. King Charles I was executed in 1649 and two years later his son Charles returned from exile in an attempt to regain the throne. He rallied his supporters at Worcester but on 3 September 1651 the royalists were decisively defeated by Oliver Cromwell's New Model Army. For the next six weeks the fugitive evaded Parliamentarian forces by travelling in disguise between a succession of safe houses. A reward of £1000 was offered for his capture and anyone caught helping him faced execution. With the aid of a network of royalist supporters, he finally sailed for France on 15 October. Charles II was restored to the throne in 1660 and the story of his daring escape nine years earlier became a cornerstone of Royal propaganda. Episodes such as the king taking refuge in the 'Royal Oak' passed into popular culture through written accounts, plays and prints. However, the scale and ambition of Isaac Fuller's painted treatment of the narrative is unique.

This scene depicts an event on 6 September when Charles II was escorted by the Penderels to nearby Boscobel Wood, where he met Colonel William Careless. Careless had fought at the Battle of Worcester and was also a fugitive from Parliamentarian forces. It is notable that Charles II is not shown as the 21-year-old he was in 1651 but as the mature king following the Restoration.

#historical scene#historical art#oil on canvas#painting#boscobel wood#king charles ii#william carlos#richard penderel#loyalist supporters#colonel william careless#fugitive#artwork#fine art#oil painting#male figures#conversation piece#narrative art#costume#hat#british history#british monarchy#english culture#english art#isaac fuller#english painter#european art#17th century painting#national portrait gallery

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi , your favourite monarchs are Richard iii and Charles ii . Do you see one similarity between them ? They were both in their 30s when they became King 👑

Hello! I sadly don’t see many similarities between Richard and Charles but I have a few!

1. They were both in their 30s when they became king (as you mentioned)

2. They both fought battles for their cause (I.e., Bosworth, Tewksbury, and Worcester)

3. Both of their fathers died when they were young. Charles was 19, and Richard was around 7 (from what I know).

4. Both of their siblings sucked. Edward IV (Richard’s eldest brother) married Elizabeth Woodville instead of Eleanor Talbot which ruined LITERALLY EVERYTHING (I hate Elizabeth Woodville so much istg) FOR EVERYONE!!!! And James II (Charles’s younger brother) was a stinky smeller who got thrown off his throne because he had green aura and sucked.

But other than those four, not much!

#ermmm what the scallop#yapping tag#answered ask#king richard iii#richardposting#king charles ii of england#charlesposting

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

so, coa was patron to provincial appearances as well but there are some interesting gaps...1517-1518 are her first, then 1520, then a gap of eight years (!) of none which seems to coincide with henry fitzroy's birth and ennoblement...another gap, then she continues to have them during the great matter, one twice a year (in 1530) which was unusual for her, her last in 1531, the year of her exile (make sense)...

anne boleyn made large use of them (unsurprising, she had an uphill battle in reinforcing her legitimacy as queen to the public), from the year of her coronation onwards... five appearances in 1533 alone (in exeter, worcester, cambridge, crowle 2x), one in 1534, two in 1535...

"David Starkey writes that Anne ‘wanted to make sure her title as queen would be unimpeachable’. Henry, Anne, and her faction realized Katherine’s popularity with the commons [...] ; the ceremonies surrounding her formal entry into London and her coronation were designed to exceed and overshadow any celebrations connected with Katherine — in other words, to advertise Anne’s status as the rightful queen. So perhaps it is not mere coincidence that the Exeter records identify a troupe as Queen Anne Boleyn’s minstrels in 1533, the year of her coronation, and birth of the future Elizabeth I.

Anne [...] seems to have appropriated Katherine’s entertainers, as well as John and William Slye from Princess (now Lady) Mary’s defunct troupe. Queen Anne’s players also appear in records from Worcester in 1533, and from Cambridge, and Crowle, Worcestershire, where they performed twice. In just this one year, records published to date indicate that provincial appearances by Anne’s performers equal the total number of such appearances by Queen Katherine’s performers over her entire twenty-four years as Henry’s queen. Anne’s performers continued to tour under her name for the following two years, appearing in records from Battenhall, Worcestershire in 1534, and from Dover in 1535. Might it be that Anne believed it prudent to advertise her status as queen while the popular ex-queen was still alive in ‘retirement’ fifty miles from London at Kimbolton? It does seem probable that Queen Anne used drama, as did Thomas Cromwell and the earl of Oxford, as a means to propagandize [religious] reforms and the break with Rome."

Advertising Status and Legitimacy: or, Why Did Henry VIII’s Queens and Children Patronize Travelling Performers?, James H. Forse

jane seymour, of comparable frequency, although not to as great an extent as anne's first year as queen (three, in 1536), none for anne of cleves, katherine howard one performance for each year as queen...

"During Christmas celebrations in 1540, her players entertained the court with a play named Godly Queen Hester. Several scholars believe the play was meant as an allegory, paralleling the biblical queen Esther, her sponsor and relative Mordecai, and their roles in the downfall of the evil minister Haman with Queen Catherine Howard, her uncle Norfolk, and the downfall of Thomas Cromwell."

Advertising Status and Legitimacy: or, Why Did Henry VIII’s Queens and Children Patronize Travelling Performers?, James H. Forse

katherine parr one for each year as queen except then four for 1547 alone, interesting (trying to promote herself for what she believed was likelihood of regency, maybe?), until widowed:

"Possibly because of these uncertainties at court, and her Protestant sympathies, Queen Catherine’s entertainers were as active in the provinces as had been those of Anne Boleyn. Their presence in the provinces is recorded every year during her tenure as queen consort — in accounts from Canterbury (1543), Cambridge (1544), Dover (1545 and 1547), Maldon, Essex (1546 and 1547), Norwich (1546), and Bristol (1547). Given the fact that Henry gave her free reign in 1544 in reorganizing her household, it seems plausible that Catherine herself may have sent her players out to promote her status, and possibly also Protestant reforms. Catherine was a patron of Nicholas Udall, who wrote two anti-papal plays, Ezechias and De Papatu. She could have been following the examples of Queen Anne Boleyn, the earl of Oxford, and Thomas Cromwell, whom we know were connected to an acting company led by John Bale that performed pro-Protestant plays about the kingdom. We get a hint that such might be the case from the Norwich records, which indicate a reward to her players ‘for an interlude whose matter was the market of mischief’. This interlude might have dramatized Thomas Cromwell’s exposé of the Rood from Boxley Abbey in 1538, when, in marketplaces in Maidstone and London, he revealed the hidden machinery that made the lips of the idol move."

Advertising Status and Legitimacy: or, Why Did Henry VIII’s Queens and Children Patronize Travelling Performers?, James H. Forse

on to henry viii's children...in the next installment.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

At some point, of course, word of these developments was bound to reach the king. The defection of the earl of Worcester from the prince's entourage would have been the point of no return in this respect, although as Hotspur had every right to be in Cheshire, and as his true intentions may not have filtered through to Shrewsbury immediately, it must have seemed at least possible that the king might not learn of the insurrection until after the prince's army had been defeated. Henry would not have been able to raise an army and march to within reach of either of the two areas of revolt for another week or so, and his military and strategic problems would then have been formidable. If he had remained in the south in an attempt to levy a really large force, his enemies would have had ample time to converge on him. If he had set off immediately to gather troops on the way north, he would have been in a perilous predicament when he reached the north midlands. Whichever direction, west or north, he were to take and the choice had to be made he would be advancing into hostile territory while giving the forces of whichever of his enemies he chose not to confront ample time to close on him from the rear. As the earl of Northumberland already controlled, or had the potential for raising, the rebel forces of the north, there was no reason why he should move out of his ground until the last days of July the earliest time at which the king might be expected to arrive in the critical area. Moreover, there were reasons why he should remain in Northumberland for the greater part of the month. After Hotspur's sudden departure at the beginning of July, the troops on the Scottish border needed a leader in the event of the outbreak of hostilities. If there had been collusion with Scotland, of course, this would not have been necessary, but in that case it would also not have been necessary to leave the border army at its post.

Peter McNiven, "The Scottish Policy of the Percies", Bulletin of the John Rylands Library, vol. 62, no. 2 (1980)

#henry hotspur percy#henry percy 1st earl of northumberland#henry iv#henry v#thomas percy 1st earl of worcester#historian: peter mcniven#the battle of shrewsbury#the percy rebellion#percies

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

29th September

Michaelmas

St Michael Expelling Lucifer and the Rebel Angels by Peter Paul Rubens (1622). Source: Thyssen Bornemisza Museo Nacional website

Today is Michaelmas (literally the Mass of St Micheal). Michael is quite different from most saints in the Christian calendar in that he is a supernatural being - an Archangel - charged by God with protecting the holy sites of Judaism and Christianity. His ultimate act of divine defence was to save Heaven itself from the beautiful but evil Archangel Lucifer and his insurrection against God’s rule. Michael led the loyal Angels in a mighty battle against Lucifer and his rebel Angels, defeating him and casting his rival and his acolytes out of Heaven and into Hell. On the long descent, Lucifer and his followers were corrupted into Satan and his horde of devils. Embarrassingly, the would-be King of Heaven landed painfully on a bramble bush leading him vengefully to blight the brambles at the end of September every year.

Michaelmas was characterised by many end of Harvest fairs , where people traded in jobs, livestock, gossip and drinking. Frequently the farm workers travelled to the fairs to spend the money they had earned in the late summer bringing in of the harvest. As a result the fairs frequently became rowdy alcohol-fuelled events, leading some organisers to formalise the violence. At Kidderminster and Worcester, an hour of fruit fighting, called Kellums, was allowed between the standing down of the old bailiff and the accession of his successor. Michael, as mentioned yesterday, as a muscular and powerful Christian figure, was often conflated with pagan gods. His commemoration at St Michael’s Mount, near the attested old pagan site of Glastonbury Tor, is unlikely to be a coincidence.

The main dish at Michaelmas was goose, either arising from a mishearing of St Michael’s Biblical reading (the Latin phrase ‘esse intentos’ became ‘goose intentos’) or because Queen Elizabeth I celebrated the defeat of the Spanish Armada with a feast of cooked goose every Michaelmas. Neither origin myth is particularly credible. More likely, geese became payment in kind to agricultural workers at the end of Harvest.

#st michael#michaelmas#lucifer#satan#brambles#harvest fairs#pagan religion#Kellums#goose inentos#Harvest#glastonbury tor#st Michael’s Mount

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

On 24th May 1616 , Scottish politician was born.

Maitland was Charles II’s deputy in Scotland, he was another in a long line of leading figures in Scotland who “bobbed” between sides, Maitland was originally a fully paid up member of The Covenanters, he even carried the cause into England when Cromwell needed the Scots help to usurp Charles I, he was present at the signing of the Solemn League and Covenant by both Houses of Parliament and the Scottish commissioners on 25th September 1643 in London, he stayed on in London to negotiate the reform of the Church of England.

Born at Lennoxlove House (then Lethington), near Haddington. He married the Countess of Dysart. He was captured at the Battle of Worcester imprisoned in the Tower of London and his estates were forfeited.

They were restored under King Charles II, who made him Secretary of State, a position in which he exercised enormous power, regarded as the ‘uncrowned King of Scotland’. He was the 'L’ in Charles’ so-called 'CABAL’ administration,(“CABAL” stood or the names of the five Privy Councillors Clifford, Arlington, Buckingham, Ashley-Cooper, and Lauderdale) running Scotland without hindrance, despite corruption and intrigue, resisting the reproach of his rivals.

Although having the reputation of being unscrupulous and crude, he was created Duke of Lauderdale in 1672, having inherited the Earldom of the same name from his father in 1645. When not in London or Edinburgh, he made his home at Thirlestane Castle, which he rebuilt and extended. He also refurbished Lennoxlove, the family home in East Lothian.

He compromised with the Covenanters while maintaining the ultimate authority of the King, but this strategy failed leading to the Battles of Drumclog and Bothwell Brig and his fall from power.

John Maitland died at Tunbridge Wells and the Dukedom ceased with him. He is buried in the crypt below the Lauderdale Aisle in St Mary’s Church, Haddington.

12 notes

·

View notes

Note

Can you talk about Edward IV of England's ministers who are very close and unknown to the general public, and only those who have carefully studied history know about them?

There are a few unknown figures:

John Neville, Earl of Kent, brother to Montagu and the Kingmaker who was decisive in battles against the Lancastrians and became Admiral of England. He died too young (in 1463) to show the full extent of his influence.

John Tipfot, Earl of Worcester, who had an impressive collection of offices and was mainly charged with purging Lancastrian through the 1460s before being executed during the Readeption. He was an original figure who studied law at Padua and travelled to Jerusalem

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Minstrel, the Maiden, and the Knights of Hellfire - Chapter 14

Pairing: Hellcheer, Medieval AU

Summary: England, 1139: the civil war between King Stephen and Empress Maud looms large, threatening to tear the country in half. For Ed and his band of traveling minstrels, however, the more pressing matter is how to survive the upcoming winter, now that they were tossed out by their latest patron. When they stumble upon a naïve pageboy looking for warriors to escort the lady Christiana to safe haven in Wales, Ed comes up with a daring plan - pose as knights, take the job, and collect the reward. After all, how hard can it be? What Ed doesn't count on is endless battles, treacherous roads, marauding bandits, Lady Christiana's pompous fiancé, and his own growing attraction to the fair maiden herself...

Chapter warning: mentions of injuries, angst

Chapter word count: 4k

Chapter 1 - Chapter 2 - Chapter 3 - Chapter 4 - Chapter 5 - Chapter 6 - Chapter 7 - Chapter 8 - Chapter 9 - Chapter 10 - Chapter 11 - Chapter 12 - Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Pain.

Pain and darkness.

Pain was the first thing he became aware of. Its center was somewhere around his right shoulder blade, and from there, the pain radiated all through his body, until even his extremities were tingling and twitching. It felt as though his flesh had been torn apart and then put back together by an inept seamstress.

The next thing he became aware of was the darkness. He opened his eyes—with some difficulty, for his eyelids seemed strangely heavy and stuck together—and for a moment, wondered if he had truly awakened at all, for there was darkness all around him.

A red glare flickered at the edge of his vision, like the fire of Hell. Somehow, this thought comforted rather than frightened him. Hellfire... he would be right at home there.

Then the glare brightened, and darkness resolved into shapes. He was lying on a cot, covered with a wool blanket, rough but clean and warm. A turn of his eyes—he couldn't quite turn his head yet—showed that there were similar cots in rows on either side of him, some empty, others occupied by faintly human forms. A shaft of paler light at one end of the room may be the moon shining through the shutters of a single small window. The room was quite large and lofty, so despite the lack of windows, it remained light and airy.

The glare came closer. Ed turned his head and winced as a new spear of pain lanced through his shoulder. The glare turned out to be a lantern held in the hand of a monk of middle years, who was walking between the rows of cots, stopping occasionally to check on the occupant of this or that cot. Eventually, he came to Ed. In the warm light of the lantern, his weathered but kindly face reminded Ed of Wain's. Even his shining tonsure put Ed in mind of Wain's balding head.

"What, awake already?" the monk said upon seeing Ed, and his voice, with its Shropshire accent, was another reminder of home that put Ed at ease. "I didn't rouse you with my stirring and shuffling, did I? Here, have a drink of water." Pouring from a jug on a low table next to the cot, the monk held a cup to Ed's lips and supported Ed's neck to help him drink.

The water, sweet and fresh, cleared some of the haze from Ed's mind. "Where am I?" he said. His voice sounded thin and far away.

"Bromfield Priory, near Ludlow. You were brought in by your friends. I understand you were attacked by bandits while fleeing the attack in Worcester?"

His friends! The pain was momentarily forgotten as anxiety flooded Ed's heart. The next question struggled to form on his lips, stalled both by his physical exhaustion and the fear now plaguing his mind. His friends... one of them in particular...

The monk, guessing at the source of Ed's agitation, held up a calming hand. "Don't trouble yourself, my son," he said. "Your friends are all safe. You've taken a crossbow bolt to the shoulder, but I've gotten it out and patched you up as best I could. What you need now is rest, so that you can heal." He took a vial out of the scrip at his belt, tipped a few drops of something into the cup of water, and proffered it to Ed again. "Drink. It's poppy juice. It will help you sleep."

Ed gulped down the cloyingly sweet liquid, but the unpleasant taste soon vanished as sleep took him once more. Safe... they were safe... she was safe. That was all that mattered.

***

When Ed woke again, full daylight was shining through the window, and he found himself looking at Geoff, Gareth, and Tadhg. The anxious, watchful look on their faces broke into grins of relief the moment he opened his eyes.

Ed lifted a hand—his left—to his face. "I can't believe there would come a day when I am glad to see your ugly visages," he groaned. His friends' smiles all widened.

"There he is," Geoff said. "We're glad to see you too."

"You've given us quite a fright," continued Gareth.

Tadhg said nothing, but he poured Ed a cup of water. The pain in Ed's shoulder had subsided, making him aware of other, lesser pains around his body—soreness in his limbs, an ache in his head, and a gnawing emptiness in his belly that might be hunger.

"How long have I been here?" he asked, after taking a sip of the water and nodding his thanks to Tadhg.

"Two days now," said Tadhg, jumping up. "Getting hungry, are we? I'll go and see if Brother James has something for you to eat."

"How did we get away?" Ed noticed that the gash over Geoff's temple had been bandaged, and Gareth's arm was in a sling.

"We were lucky," said Geoff. "Lord de Dinan, the castellan of Ludlow Castle, must have caught wind of bandits around his land, for he set his men on nightly patrol of the area. We ran straight into them, and they escorted us here."

"And Vecna?"

"We told the captain of the guards about their lair, but by the time Lord de Dinan's men arrived, it had been abandoned. Likely, Vecna and his men are in hiding, or they've fled to the south. Either way, we're safe from them."

Ed lay back with a grateful sigh. At that moment, Tadhg came back with a steaming bowl of thin gruel. "All you're allowed at the moment," he said, "but Brother Rhys—that's the infirmarer—reckons you'll be well enough for solid food soon."

With his friends' help, Ed sat up in his cot with his back against a pillow to cushion the wound on his shoulder. It was difficult, eating with his left hand, especially when he was so hungry that he hardly tasted the gruel, but he managed.

"And—Christiana and Dustin and Maxime, are they here as well?" he asked, after the edge of hunger had been blunted by a few spoonfuls. Despite his public declaration of love, he still felt a little shy talking to his friends about Christiana. It had been bothering him that she hadn't come to see him in the infirmary, but he supposed with all these men around—they might be monks, but they were still men—it would be best for her to stay away.

At the mention of Christiana, the three boys glanced at each other. Ed caught that involuntary, furtive glance, and the dormant fear rose in his belly again, making him forget his hunger.

"Christiana," he repeated, "she is safe, isn't she?"

Again, that surreptitious look passed between his friends, and Ed's fear grew.

"She is safe," said Geoff, after a while.

"Is she here?"

"She's close," said Gareth.

Had he been in full possession of his strength, Ed would have seized his friends by their cottes and shaken them until the truth fell out of their ears. But as he couldn't move without sending stabs of agony to his right shoulder, all he could do was sit and stare at them while fear and doubt tortured his heart and his mind.

At last, Tadhg lost his patience. "For goodness' sake, we might as well tell him!" he exclaimed. Turning to Ed, "She's at Ludlow Castle. Dustin and Maxime are with her."

Ed allowed himself a breath. "Well, I suppose it's more convenient for her to stay there than at the priory," he said. The shiftiness on his friends' faces remained, and a new fear emerged. "Does Lord de Dinan know who she is? Did he take her?" This entire area was loyal to Stephen, so if Lord de Dinan knew Christiana was the daughter of a known supporter of Maud...

"Lord de Dinan didn't take her," said Tadhg. "She was taken there by Sir Jocelyn."

The name fell on Ed's ears with a horrible clang, or perhaps it was simply the sound of the spoon being dropped into the bowl of gruel. Ed stared at his friends, uncomprehending.

"Sir Jocelyn de Craven, her betrothed," supplied Geoff helpfully. "He's at Ludlow Castle, a guest of Lord de Dinan. I believe he came here to negotiate Christiana's ransom with Vecna. He was with Lord de Dinan when we were brought to the priory."

"And he took Christiana to the castle with him," concluded Gareth.

"And she went with him?" Ed asked, incredulous. "Without protest? And you let her?"

His friends had the grace to look guilty. "There was nothing any of us could have done," Gareth said, fixing his eyes on the flagstones on the floor. "They had us surrounded."

"I don't believe it," Ed said. "She wouldn't submit to him so easily. Not when she's gone through so much to get away from him." Not when she loved me.

Geoff shrugged. "Perhaps between Jocelyn and Vecna, she decided that Jocelyn would be the lesser evil."

"She is only a means for him to worm his way into the King's favor!" Ed shouted—or tried to.

"Would that be a bad thing?" said Geoff. "The Empress may be gaining ground, but most of the country is still under Stephen's rule. It's safer to be on the King's side."

"I don't think Jocelyn meant her harm," Gareth added. "He seemed truly glad to see her, and he's planning an extravagant wedding for her—I heard from Lord de Dinan's groom that there's to be a feast, and a three-day celebration with all sorts of games, including jousting. Lord de Dinan is hosting it—"

"I don't want to hear about his wedding plans!" Ed hissed. Then, in a vain attempt to find sense in the nonsense, he continued, "He may not be as bad as we thought, but what can he have to offer her?"

"Wealth," said Gareth.

"She cares not a jot for wealth!" He was arguing with himself as much as his friends.

"Protection," said Geoff. That word silenced Ed with the cold force of a deep freeze that covered the whole countryside in ice without warning. Protection... yes, regardless of his loyalty, someone in Jocelyn de Craven's position could offer Christiana much better protection than Ed ever could. What had Ed done for Christiana except to get her into danger? Since traveling with him, she had been attacked, injured, nearly drowned, and kidnapped. Even when he tried to save her, he had only put her directly in the path of the outlaws. And when she needed his protection the most, he had been laid up with an arrow in his shoulder, insensible and useless.

After all, what did he think was going to happen? That they would live happily ever after, in her little farm in some Welsh valley or traveling the roads with his minstrel troupe? A child's dream! Now that he thought about it, she had never really said she loved him. She had kissed him, true, but perhaps that had not been love at all. Perhaps he had deluded himself into thinking so. Fool!

And even if she had loved him... perhaps it was better this way. She would never know the truth about him. She would go into her marriage thinking of him as a noble knight who had simply failed to save her, not as a baseborn minstrel who had deceived her.

Ed pushed the gruel away, feeling as though he couldn't swallow another morsel without choking on it. Thankfully, at that very moment, Brother Rhys, the kindly monk who had greeted Ed first upon his waking, came in and shooed his friends away so Ed could have his rest. After one last pitying look at their fallen leader, Geoff, Tadhg, and Gareth filed out. Brother Rhys checked Ed's bandage and pronounced that his wound was healing nicely, so he would be up and about in no time. As the infirmarer moved to the other patients, Ed considered asking for some more poppy juice to help with his pain. In the end, he decided against it. No amount of poppy juice could alleviate this pain, for it was not his body that ached, but his heart.

***

The next day, true to Brother Rhys's prognosis, Ed was able to get out of bed. First, he must present himself to Prior Osbert to give his respect and thank the Prior for kindly sheltering him and his friends. The Prior, a tall, proud-looking man with silver hair, barely looked down his patrician nose at Ed and waved him impatiently away. Ed had the feeling the Prior was afraid the minstrels' presence would be a stain on the unblemished face of his godly house, but as he couldn't have turned them away for fear of appearing unchristian, he now wanted them gone as soon as possible.

After the audience with the Prior, Ed was free to wander around. Bromfield Priory was not large as priories went—during their travels, Ed and his friends had sheltered at a good number of religious houses, including, on one memorable occasion, a convent, so he had a good idea of sizes—but it was neatly set up, with the noble church of St. Mary's to one side of the gatehouse, followed by the cloister and the guest hall, all surrounding a square court. Next to this cluster of buildings was the garden, where Brother Rhys grew most of the herbs for his remedies, and the stable, above which Ed knew the lads were staying, as they were deemed not rich and high-born enough for a room in the guest hall.

As Ed walked down the cloister, he met some young monks and novices, who eyed his long hair and wild appearance with wariness or curiosity. He ignored them. The older monks, who were set in their ways, paid him hardly any mind at all, which he much preferred. In his state of mind and heart, he wanted no company, not even that of his friends.

Rounding a corner, Ed heard the soft sound of music and stopped in his tracks. There, tucked away at one end of the cloister, was a little room, a workshop. The table was strewn with quills and pieces of parchment, rolls of gut string and wood shavings, and the walls were hung with all kinds of instruments in various states of repair. A monk, past fifty at least, also tall and white-haired like the Prior, but much slimmer, with a thin neck and long nose that made him look like a heron, sat amongst that happy mess, gently drawing a bow across a rebec. Ed hesitated, afraid of being dismissed again with contempt, but just then, his shadow fell across the open doorway, causing the monk to look up. A friendly smile broke out on his face, and Ed breathed a little more easily.

"Aren't you one of the minstrels fleeing the sack of Worcester?" the monk said.

"I am, Brother—"

"Call me Elias." Seeing Ed's gaze on the rebec, the monk lifted the instrument to the light. "Do you play?"

"Not the rebec," Ed replied. "It's a beautiful instrument though."

"It will be, once I finish fixing it." Brother Elias ran a hand over the rebec's pear-shaped body, gently as a mother caressing her child. "I've seen your instruments when your friends brought you in," he continued. "All nice pieces too. The rebab of your Moorish friend is especially fascinating. An ancestor of the rebec, I believe, though I've never seen one outside of the Holy Land."

"You've been to the Holy Land?" Ed asked, astonished.

Brother Elias smiled. "Indeed. I fought at the Siege of Jerusalem under Robert of Normandy. It was only much later that I took the cowl. Now I'm the precentor of Bromfield, and I make and repair instruments in my spare time. This one"—he lifted the rebec again—"belongs to Lord de Dinan's troubadour, but something is causing it to not sing true. Though I can't seem to work it out..."

Ed didn't realize he had wandered into the workshop until Brother Elias lifted a psaltery down from its peg and pressed it into his hands. "If the rebec is not your style, why not give this a try?" the monk said. "I should have a plectrum for it somewhere."