#bigger than the traditional palisman at least

Text

hc that hunter becomes Dell's apprentice and eventually carves a giant wolf palisman that acts as a therapy dog for his ptsd

#it is very important to me that the wolf is giant and fluffy#bigger than the traditional palisman at least#also the wolf is black for no other reason than i have already imagined it in my head#bird likes to chirp#toh#hunter wittebane#toh hunter#hunter toh#the golden guard#the owl house#dell clawthorne

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

Decided to post the essay I wrote a few days ago. Of course, this isn't meant to shit on anyone, but to work through my feelings on TOH's themes and how I see the fandom working through them.

TOH has a very – let’s say uneasy relationship with its fantasy elements—or at least, that’s how the fandom has received them. I just saw someone talking about how Luz shouldn’t have gotten a Palisman of her own because she “doesn’t need to look any more like Azura,” considering that Luz’s whole thing at the beginning of the series was needing to better “tell fantasy from reality.” But I feel like that’s only getting half the point—the issue with not being able to tell fantasy from reality rests, as the series argues, with expecting the world to cater to you and then lashing out when it doesn’t.

The series makes this most clear with Belos, who rejects the traditional high fantasy genre signifiers as spiritual pollutants and yet is living in as much of a fantasy world as Luz was. “[He needs] to be the hero of his own delusion” locates Belos’s major flaw—in a character way and in a thematic way—in his refusal to see himself as just another part of the world, rather than its center. All of this is spoken to us directly by the embodiment of the Boiling Isles and its magic. This character flaw is then reinforced by how Belos gets defeated and starts rambling on about how humans are innately “better than this” Because Reasons.

I think part of this disconnect might be happening because we’re used to anti-escapist stories rejecting the fantasy world in its entirety. For example, Ready Player One ends with the reveal that the creator of the VR world—it was called the OASIS, wasn’t it?—regretted not spending enough time in the “real world,” and the main character rectifies this by enforcing a weekly one-day service outage. Even though the book explores reasons why people would want to escape into the VR fantasy, including escaping the confines of marginalized identity categories like gender and race, it still asserts that you’re missing out by leaving the “real world” behind. I think also of modern fantasy stories with creatures like vampires and werewolves that bend over backwards to justify why being a human is still totally the best option— “Be glad of your human heart, Feyre,” and so on. Even in series where the human main character becomes inhuman, it’s often through force—characters like Feyre and Elena Gilbert are killed and then revived as monsters, but only Bella Swan actively wants to become one. (It really is the equal-but-opposite response to the question Robert McRuer says is asked of disabled people IRL in his article about compulsory able-bodiedness: “Yeah, but in the end, wouldn’t you rather be like me?” In both cases—whether disabled or super-abled—the normate, abled, “regular” human position has to be reinforced as the ideal.)

And let’s be real, it’s all cope. We can agree it’s just cope, right? But even besides that, I think we also need to keep in mind that, contrary to what internet discourse would have you believe, subverting tropes is not good writing in and of itself — subversion and deconstruction need to be ways of creating meaning within the work, rather than the meaning itself.

I think, then, we can see TOH’s conversation with escapism from s1 to s3 as a way of asking, “What parts of our childhood should we keep?” In Luz’s case, like in many of our own childhoods, the fantasy elements are from the actual fantasy genre because Luz wants to imagine a bigger life for herself than Earth allows, one that is scary and dangerous but in the end still caters to her/us. (See also Freud’s concept of the family romance, wherein a child dreams that their parents aren’t their “real” parents and that their “real” parents are magic space fairy royalty who will one day reclaim their child and everything will be awesome forever.)

In episodes like “Witches Before Wizards,” these genre signifiers provide Luz with a set kind of “script” for how she believes interactions should go—the disappointment and restlessness she feels in the episode is from the fact that it’s not catered to her just because she’s there, in a similar way that Belos believes humans are better just Because They Are. Worth noting that even in that episode, the “reality” Luz needs to learn to accept is still based in a fantasy setting—signaling that the word “fantasy” in “differentiate fantasy from reality” should not be about the genre or the act of consuming fantasy in and of itself. Season three then literalizes this with The Collector turning people into puppets and acting out “The Owl House” as a game with suffering participants.

Conversely, season three adds more nuance by revealing that Luz’s hyperfixation stems from her relationship with her father. The season does a lot to explore the relationship-building potential of fiction, from Amity suggesting her and Luz dress as Hecate and Azura to the reveal that Camila is a secret Trekkie.

A fellow autistic person once described their special interest not just as something they’re obsessed with, but as part of how they processed the world. We can see this kinda play out in Camila’s conversation with Luz right before Stringbean hatches: she says she has forgotten the “Astral Oath” and responds to Luz’s question of her being a “secret nerd” with the admission that she shouldn’t have let her own fears of and experiences with being non-conforming compel her to try and change Luz. The Astral Oath and how it played out within Cosmic Frontier provided a framework for Camila that she admits she should have followed: “My biggest mistake was trying to protect you by changing this beautiful, good witch into something she wasn’t.” The best things about Luz are also the things that make her more drawn to the fantasy genre.

The rampant egoism of the genre should be left behind, the show says, but not the good lessons and the relationships you’ve built from it.

This anti-egoism does, of course, run up against the fact that Luz is still the main character. If Luz getting a Palisman makes her too much like Azura and therefore undermines the message, then honestly I don’t see how the final battle itself isn’t just a colossal fuck-up. Not even in the sense that Luz got Titan magic, which I have seen people say is now suddenly Luz being A Chosen One all along, but in the sense that Luz straight up shouldn’t have been in the final battle at all. (Honestly, if you want YA with a good anti-egoism message imparted through its structure, you’re looking for Robert Cormier’s The Chocolate War—book, not movie.)

I said on Twitter while I was reading Charlie Ledbetter’s “The Dysphoric Body Politic” that TOH has an interesting relationship with its escapism messaging because Luz DOES leave the human world. Even though she had to finish high school in the human world, the finale makes it clear that she’s been putting all of her spare energy and labor into the literal rebuild of the Boiling Isles. She entirely gives up on making a life for herself on Earth.

This isn’t super surprising, (I was always sure it would happen) but I do think it’s where the uneasiness—the messiness—between TOH and its genre comes into play. Yes, Luz needed to dial back her daydreaming and yes, her being in the demon realm ultimately led to it almost being destroyed, but it still is the worst possible ending if she doesn’t get to stay there.

In the article, Ledbetter, a transmasc who discovered themselves through fandom, writes that “Escapism is not a departure from reality. Rather, escape decenters the hegemony of oppressive systems that announce themselves as real and creates space to imagine alternatives.” And yet within the show, it’s a closed circuit—the threat to diversity and self-expression comes from the human realm, and yet there is no attempt to save it. Ledbetter, writing of fandom’s political potential, suggests using fanfic to imagine alternatives specifically so we can give ourselves the drive to try and enact them in the real world.

TOH’s sister show, Amphibia, gives us a taste of this in its finale: in the ten years since the Calamity Trio has left, the once-evil king lives out his final days planting seeds, and the girls themselves are dedicated to either educating others or creating art. They honor the memories of their childhood fantasy—Sasha with two crossing swords as a patch on her jacket and a charm dangling from her rearview mirror, Anne with her entire career—but the portal is closed. It’s not coming back.

Given everything TOH does in season three to reaffirm the value of fantasy as a lifelong interest, though, I think what it wanted to avoid suggesting, like a lot of traditional portal stories do, that the fantasy world is the world of childhood and needs to be escaped. Aslan tells Peter and Susan, after all, that they’re getting too old for Narnia. Peter and his siblings return there only in death; Susan isn’t so lucky. If Luz shouldn’t have gotten a Palisman, something which symbolizes she’s discovered a fundamental truth about herself and has “earned” her place as a Witch, then honestly she shouldn’t have been able to come back to the Boiling Isles, either. How many of us would've been happy with that?

If we want to square this with the show’s politics, I think we can read this as the show saying that, yes, there are some things you have to do as a child, but once you’re free, you aren’t obligated to stay with the society and people who won’t ever see you for who you are. In a way, Luz going back and forth between the human and demon realms parallels the teenage fantasy fan, making space in their lives for fandom as a place of joy and connection after all the boring hard “adult” work is done for the day. You don’t have to leave it behind; building outside of the system and making your life centered around your joy is hard work, yes, but worth doing.

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

Agony of a Witch: Analysis --Part 2 of 4--

Part 1: https://anirbasstuff.tumblr.com/post/627207417804013568/agony-of-a-witch-part-1

Two important things here: The place where the fire came from was that place that I feel is like a magic extractor. On the other hand, I really feel that the emperor cannot listen to the titan, if so he could follow his advice and not be so weak.

This catches my attention, it is the only cameo we have of Kikimora from behind, she has two hands as hair. We can add that to the symbolism that I had already explained.

Well, I did a little research on the name Kikimora and it turns out that the Kikimora is a like a dream spirit and is in charge of taking souls to hell. I'm curious about what I found about her: "Sometimes she usually appears before the death of a family member, and her scream is heard just like that of the banshees (this makes me think that someone is going to die). Describes as a middle-aged woman, a little crooked, ugly, thin and with a long nose, no bigger than a mouse. Her hair is covered with a cloth). The only thing is that the description does not fit, what if rather the emperor wants someone like a kikimora but he used a witch instead?

On the other hand, the kikimora is a partner of a Domovoi (it is a deity), so we could say that it is the emperor, its description catches my attention:

"Tradition says that every house has a Domovoi. It does not become a demon unless it is displeased with poor housekeeping, foul or sloppy language. The Domovoi is seen as the guardian of the house, and some sometimes he helps with small repairs. Traditionally he is treated like a member of the family, although no one sees him, and presents are left for him at night"

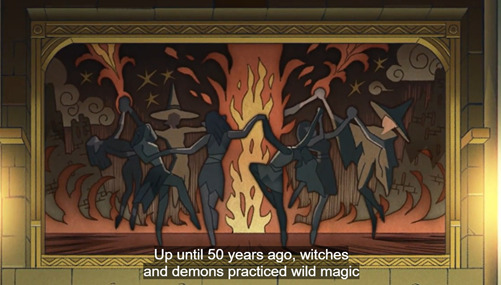

We know that Eda knows how to practice wild magic, because that is how she taught Luz, this means that maybe she is at least over 50 years old, otherwise it would be more difficult to know where she learned it from.

And they tell us it was something that dishonored the Titan. I wonder if it was the emperor who told them that this dishonored the titan, because if so it would be very convenient. The emperor is supposed to be the only one who can speak to the "titan", so this could have been invented so that witches were forbidden to exercise wild magic.

Then, unsurprisingly, the emperor sees an opportunity to rise to power by promising the people new hope. Let's say something like this: Imagine the emperor as anybody against witches for some reason (maybe because he is human and envies his powers) then he begins to say that wild magic is bad, that only magic used can exist thanks to the magic bile. As wild magic was something new, not everyone believed in its efficiency and safety and the emperor sees this opportunity to gain power, admiration and also control the people. That is why he establishes the covens, in order to maintain control of all magic. The emperor is not bothered by Eda engaging in wild magic, nor by teaching Luz (I would dare say he wanted to learn wild magic but maybe he never gave it a chance), but he believes that through feeding on magic bile and / or palismans, will obtain the same power, but possibly it is not like that, because we see that it is very weak.

(By the way, does someone also think that the emperor's hands look like chicken feet and maybe the emperor has lived with a curse all this time, but has been able to control it to remain rational?)

This is also important, as we are told that the relics are reminders of the overwhelming power of the emperor. But as we saw (and Lilith knows) the objects that Luz, Gus and Willow used were really not as powerful as previously thought because they vanished with simple spells. That makes you wonder, if those are the representations "of the overwhelming power of the emperor", does that mean that the emperor is also easy to defeat, but only seems like someone very powerful?

---This is part 2---

Part 3: https://anirbasstuff.tumblr.com/post/627208284436332544/agony-of-a-witch-analysis-part-3

26 notes

·

View notes