#but in order for the patriarchy storyline to happen 'in canon' in my universe or whatever

Text

Ken immediately shielding this complete stranger when he sees a "scary unmarked black truck car" pull up. My goddamn sweetheart.

#MY SWEET BOY. I FUCKING LOVE YOU SO MUCH#love notes#💕 I'll fight for you!! - ̗̀🐎🏖️✨ ̖́-#barbie movie#ken#in this scene i wanna say in my universe he's shielding me#but in order for the patriarchy storyline to happen 'in canon' in my universe or whatever#i have to leave him alone :(#to make him say 'i miss keri ;_; why wont she spend time with me... i know! ill make barbieland like the real world :)'#'shes from the real world she will love me for it :)' spoiler alert i absolutely dont love the real world#in this scene i am comforting barbie and holding her and then going with her#while ken is like :') oh okay my girlfriend is in a scary unmarked black truck car#a black truck car i'd like to have actually. haha. youre right. they're fine. it's mattel. I KNOW i'll go back to barbieland#and tell the kens what i've learned. OH it's going to be beautiful. HA HAAAAA. BACK TO BARBIELAND#thank you [bows]#if i wasnt trying to make my universe exactly like the movie's#i would be spending so so so much time with ken#wouldnt need to bring patriarchy to barbieland when he has enough attention from me already#i'd lay with him in real grass and real flowers and feel that real sunlight on our skin#and i'd tell him how i hate the real world so much but i don't mind visiting it with him#and he'd ask why i left it. and i'd tell him and he'd hug me tight and he'd say he is so glad we met#GOD i love him so fucking much i have needed him so bad

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

THE COLOUR OF MAGIC (1983) [DISC. #1; RINCEWIND #1]

Rating: 5/10

Standalone Okay: Yes

Read First: NO.

Discworld Books Masterpost: [x]

* * * * * * * * * *

Ask any Discworld fan, and we’ll all pretty much universally agree that The Colour of Magic isn’t the pinnacle of the Discworld experience. Nobody really recommends that new readers should start here, even if it is the first book in the series chronologically. I’m pretty much a writing-order-equals-reading-order purist, for reasons best discussed elsewhere, and even I would absolutely never start people off with this one. (I tend to go for Going Postal or Wee Free Men—again, for reasons best discussed elsewhere.)

It’s not Pratchett’s best work. It’s not even his tenth best work. If I have to rate it (and I do, because that’s kind of the point, here), compared to the rest of Discworld, it’s down at the bottom of my list.

It’s pretty damn good, though, for what it is.

For me, it’s a genuine joy to read the early Rincewind books. This is because, in my head at least, it makes total sense that everything involved in them is baffling and strange when compared to the settled absurdism you get from other Discworld novels. Further into the series, it all feels a lot more comfortable and fleshed-out: yes, the things Pratchett writes about are often genuinely ridiculous, but usually the setting explains those things and packages them up neatly enough to make them acceptable. And the characters treat everything as perfectly normal, business as usual, so the reader is gently encouraged to do the same.

Thinking about it, I would argue that a lot of the Discworld shenanigans aren’t all that different from a lot of the real-world nonsense that we all just accept as totally normal. Discworld nonsense and our nonsense just come from different places. For us, it’s stuff like the fact that some cops still ride horses for absolutely no good reason, or that tipping is part of a server’s pay in an American restaurant, or that water is usually free but we all let movie theaters charge us like $5 for a bottle, and what’s that even about? In the Discworld, the thieves and assassins have unionized, and if you slip up, it’s entirely possible to just fall right off the edge of the world. It’s weird, and it’s not exactly fine, but it’s not about to kill us right this second, so we all just let it happen. We accept it.

This is not at all the case for our unwilling protagonist, the original Discworld hero-who-is-absolutely-not-a-hero, Rincewind. He’s scared of everything. He is a genuine, bona fide coward. Absolutely everything that happens leaves him baffled, terrified, and/or dismayed, and to tell the truth I unconditionally respect all of this about him, because most of the absolute bullshit nonsense going down around him is baffling, terrifying, and/or simply Not Good, and he and the reader have to learn to live with that together.

Over the course of this one novel, failed-wizard-slash-reluctant-guide Rincewind is:

Involved in burning down large parts of the city of Ankh-Morpork, because he left his friend unsupervised and the city really wasn’t ready for the invention of ‘insurance’ without the accompanying understanding of ‘insurance fraud.’

Chased, threatened, and variously menaced by a sentient suitcase known as the Luggage, which canonically has huge teeth, a mahogany tongue, hundreds of little legs, and an insatiable hunger for the flesh of its owner’s enemies. Also, it does your laundry if you leave it inside. Isn’t that nice?

Forced into a duel by dragon riders, where he must fight upside-down while wearing boots that basically Velcro-attach their wearers to the ceiling.

Captured, imprisoned, and scheduled to be sacrificed to the anthropomorphic personification of Fate in exchange for success in a scientific endeavor—specifically, checking the biological sex of the giant turtle carrying the Discworld on its back through the universe.

Dropped over the Rimfall, the waterfall at the edge of the Disc, which in Roundworld terminology is something like tripping and falling off the surface of the Earth and flying into the abyss of space.

Repeatedly almost forced to speak one of the Eight Great Spells that created the universe, which will do…something, possibly catastrophic, when spoken. No one knows exactly what it does. Rincewind certainly doesn’t. This spell attached itself parasitically to his brain years ago, and, in the meantime, has shoved all the other wizard-y type things he could have been doing right on out of there.

So, basically, he’s going through a lot. And this list isn’t everything, just the bits I pulled out by opening my book at random spots and reading a couple of lines. It kind of makes sense, in my opinion, that things feel a little topsy-turvy. Shit’s wild.

On top of that, I’d also argue that Pratchett is playing pretty fast and loose with plot and story structure in this book. It can feel sloppy at times, more like a bunch of little vignettes that have been strung together than a single, coherent storyline. The plot loosely wobbles along the tightrope strung between Rincewind’s uncanny luck, good and bad, and cheerfully-blockheaded-tourist Twoflower’s unstoppable ability to trample through the middle of every single situation that could possibly try to kill him. Very bad things happen, but somehow, they miraculously fail to die, and so Rincewind is still stuck shepherding Twoflower along through the next incident of someone or something trying to brutally murder them both. There’s no real greater plot or driving need, just Twoflower with his little camera, wanting to take pictures of every beautiful and dangerous part of the Disc.

If a rabid wolf the size of a bus came up and tried to eat him, Twoflower would take pictures of the inside of its mouth and say, “Oh, wow, I’ve never seen teeth that big before! Rincewind, won’t you take a picture of me with this magnificent beast?” And Rincewind wouldn’t answer, because he’d be half a mile away already and still moving fast, with nothing but a cartoon cloud of dust left behind to mark where he’d been.

[Here’s the boys, Rincewind and Twoflower, just doing their best. From the BBC two-part miniseries called The Colour of Magic, which actually spans the plot of both The Colour of Magic and The Light Fantastic. Yes, that is Samwise Gamgee playing Twoflower, and yes, I did get distracted by that a lot while watching. Twoflower has all of Sam’s earnest faith and absolutely none of his common sense.]

Fun!

The whole thing actually is pretty fun, though. It’s witty. It’s got something to say, even if that something is just “hey, aren’t all these identical High Fantasy Adventure books all overdramatic and ridiculous in the exact same ways?” Pratchett is writing this book as one massive joke he’s telling about the genre, the tropes, and the archetypes, and he does a pretty decent job even by today’s cultural standards, let alone the standards of 1983. Chances are that any point he’s making here in The Colour of Magic is something he’s going to make again, better, in a later book, but that doesn’t mean he doesn’t have the seeds of something here.

As a main example, I’ll point out Liessa Dragonlady, who has arguably the biggest role in one of the major conflicts of this book. Liessa is initially presented as the quintessential High Fantasy barbarian warrior lady, which would typically be more about sex appeal than any actual skill—except that Liessa is actually highly intelligent, 110% more talented and qualified as a leader and warrior than her brothers or literally anyone on the protagonists’ team, and is aware the whole time that she’s struggling against the patriarchy and her society (and the tropes) in trying to take what should be her rightful place as leader of the Wyrmberg. The sexism exists in the Discworld, not in the writing.

[Liessa from the BBC’s The Colour of Magic, wearing—no joke—a crop top armor chest piece. Actually, I think it’s technically a bikini, based on the bottom half of the armor. Or should I say the lack thereof? Classic.]

Liessa is a decent example of Pratchett’s ability to look at the tropes and the reader’s expectations, and then go and take his writing somewhere else. But even so, I’d absolutely point to Monstrous Regiment or even Equal Rites first for anyone wanting to read a really solid exploration of femininity and what it means to be a woman in a traditionally ‘masculine’ field. Or I’d suggest just about any book starring the senior witches or Tiffany Aching for examples of well-rounded female characters that demand respect in a world specifically designed to not want to give it to them.

But that’s just one example. The Colour of Magic has the seeds of quite a few really good ideas that Pratchett will explore in more depth later on.

I think those seeds are part of what makes The Colour of Magic worth a read at some point, even if it’s never going to be anyone’s favorite Discworld book. I love seeing the foundations of Future-Discworld, that settled absurdism I was talking about earlier, in this. We’ve got our proto-Vetinari, long before he had a name, being generically threatening and Machiavellian and as close to ‘cackling evil overlord’ as it’s possible to get without actually cackling, or at least without some sort of thunderstorm rumbling in the background. Ankh-Morpork is a wonderfully scum-filled cesspit of depravity and immorality. There’s no effective City Watch to kick things into a rickety and leaking approximation of ship-shape, so it’s probably a good thing that the river Ankh is so thick with pollution that you don’t need a ship to cross it—you can just walk.

There’s even some early conceptualization of Pratchett’s special brand of everyday magic, the kind that will show up over and over again in the Discworld: the idea that even with a reality full of gods and wizards and hyper-powerful, monstrous things, there’s still a lot of power in everyday, ordinary people.

Pratchett is all about belief. He preaches the importance of the self, in terms of making reality into the place we think it should be. In Pratchett’s world, the things we believe in matter, and not just in a philosophical sense. Belief is a real, tangible form of magic—in this book, specifically, Twoflower manages to summon an entire dragon out of nothing, just because he believes strongly enough that dragons should exist the way he’s always dreamed them to be. In later books, sheer belief and willpower are shown to create and fuel gods and spirits, to contain quasi-demonic entities of vengeance and darkness, and to form the backbone of every other more ‘traditional’ type of magic.

It’s nice to see the early forms of it here. I’m not going to get too into it, because it’s going to show up a lot in later books in more significant ways (I’m thinking Hogfather, Small Gods, and even Pyramids) and I don’t want to beat that horse to death just yet, but it’s one of the foundation stones of the Discworld. It’s somehow comforting to know that it’s been here since the very beginning.

It’s also funny as hell to see the stuff that Pratchett will eventually change, soften, or drop entirely as he settles into the way the Discworld will work. Did you know there are eight seasons on the Discworld? And that in my 1985 edition of the book, the footnote where he explains these eight seasons takes up the bottom half of two entire pages?

That’s one single footnote there. The first ever footnote, even, and it’s almost a full page long and utterly ridiculous. It’s incredible, and I love it a lot. I also love that almost none of the details here are ever mentioned again, and if they are, it’s never in a significant or memorable way—and Pratchett certainly doesn’t waste a whole page on any of them ever again. Well, except for Hogswatch, because Pratchett knows when he’s got a real winner. It might have taken him thirteen years, but he wrote a whole damn book about it, and we all can agree that Hogfather is a joy and a delight.

Not so much “Autumn Prime,” “Crueltide,” “Winter Secundus,” and blah blah blah etcetera whatever. I’m not ashamed to admit that I forgot them while I was literally still in the middle of reading them. And what the hell is “Reforgule of Krull”? No clue. It’s total nonsense, never seen again, and I think we can all agree we are fine with this.

On second thought, I think Pratchett does end up using Hubward and Rimward pretty regularly as directions. But without this info-dump, when reading other books, I think that even I figured out how “Hubward” and “Rimward” work on a flat plate of a world with a Hub in the center and a Rim along the outside. And I am so bad with maps and directions that I literally get confused trying to give people directions to the parking lot outside my work.

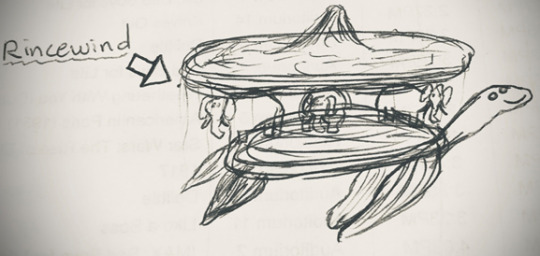

I’m no good at wrapping these things up, so I’m ending this post the same way that Pratchett ends the book: with Rincewind abruptly falling off the edge of the Disc.

[Originally, I was going to go hunt down some fanart or something, but I don’t have permission to use any of that, so instead you get my doodles off the scrap paper I steal from work. Luckily for everyone, I’m an artistic genius. The dot representing Rincewind obviously isn’t to scale, since one human person would be much smaller than that, but if it represents the size of his body and the size of his scream, then it’s basically accurate.]

* * * * * * * * * *

Side Notes:

Rincewind’s insane luck, good and bad, is because he’s a favorite of the goddess referred to only as ‘the Lady,’ since invoking her true name means she has to leave. She’s the anthropomorphic personification of Luck itself, and she’s the reason Rincewind always survives whatever terrible situation he finds himself in—but also the reason he’s stuck in that situation in the first place.

Everything that goes wrong, and the dramatic escape that inevitably follows, is because the Lady likes to play dice games with Fate, using normal people on the Disc as game pieces.

Rincewind, it turns out, is the human equivalent of her favorite Monopoly token. (The iron, maybe? It has the same sort of Looney Tunes cartoon-anvil vibe as Rincewind’s whole, well, everything.)

Death as a character makes his first appearance in The Colour of Magic. However, here it’s implied he actually is involved somehow in the killing process, and his role can be filled in by apparently random low-level demons on their days off, whereas later books make it clear he just collects and shepherds the dead onward, and actually the issue of his replacement is a big deal, cosmically speaking.

Pratchett sort of avoids this issue by claiming that Rincewind’s life timer is so complicated and convoluted (because of all the weird accidents and magical incidents) that Death just can’t tell when he’s actually supposed to die.

I guess Death shows up every time it looks like Rincewind might kick the bucket, just in case? And in that case, all the threatening stuff he says to Rincewind in these early books must be because he’s so irritated that he has to keep coming out for no reason, only to find that Rincewind has, once again, managed to survive. And maybe the low-level demon showing up instead was just, uh, Death trying to scare him into actually beefing it, this time…?

Although the Unseen University Librarian exists and is human for the entirety of this book and only this book, he does not appear at any point. He’s briefly referenced—or, at least, a librarian is referenced, but this is referring back when Rincewind was young and read the grimoire that left one of the Eight Great Spells parasitically attached to his mind. There’s no guarantee it’s the same librarian, and based on the turnover (read: murder) rate of University wizards at the time, I don’t think it’s likely that anyone managed to hold onto their job that long. On Google, I did find a thing where someone cut together some shots of him in human form from The Colour of Magic BBC show, so that’s pretty fun:

Once he’s changed into an orangutan in The Light Fantastic, he’s described as still looking a bit like the human Librarian: with that beard and hair combo, I think they nailed it.

* * * * * * * * * *

Favorite Quotes:

“Inn-sewer-ants-polly-sea.”

“She was the Goddess Who Must Not Be Named; those who sought her never found her, yet she was known to come to the aid of those in greatest need. And, then again, sometimes she didn’t. She was like that.”

“It was all very well going on about pure logic and how the universe was ruled by logic and the harmony of numbers, but the plain fact of the matter was that the Disc was manifestly traversing space on the back of a giant turtle and the gods had a habit of going round to atheists’ houses and smashing their windows.”

“Some pirates achieved immortality by great deeds of cruelty or derring-do. Some achieved immortality by amassing great wealth. But the captain had long ago decided that he would, on the whole, prefer to achieve immortality by not dying.”

“‘I’m sure you won’t dream of trying to escape from your obligations by fleeing the city…’ ‘I assure you the thought never even crossed my mind, lord.’ ‘Indeed? Then if I were you I’d sue my face for slander.’”

“It was octarine, the colour of magic. It was alive and glowing and vibrant and it was the undisputed pigment of the imagination, because wherever it appeared it was a sign that mere matter was a servant of the powers of the magical mind. It was enchantment itself. But Rincewind always thought it looked a sort of greenish-purple.”

#the colour of magic#discworld#rincewind#I don't know why I'm doing this#and I don't think anyone will actually read this#but if you do come talk to me!!#I'm going to be going through every single discworld book this year and writing up one of these#and I want to hear what people have to say#also tell me when I'm wrong because there's forty one books of material to go through and I'm absolutely going to miss stuff and mess up

3 notes

·

View notes