#charles nicolas fabvier

Text

(A while ago @apurpledust mentioned wanting to know more about Duroc's children, so here's what information I have)

Duroc and his wife, Maria de las Nieves Martínez de Hervas, had two children, both of whom died tragically young. (Hervas left instructions that her gravestone should be engraved with "To the unhappiest of mothers".)

Their first child, Napoléon Louis Sidoine Joseph Duroc, was born on 24 February 1811 in Paris. Named for the emperor and his two grandfathers (Claude Sidoine de Michel du Roc and José Martínez de Hervas), he lived for just over fourteen months. The infant’s health was never good; Duroc wrote to Bertrand in March 1812 that “[Hervas] is doing well but her son has been and always is ill”. (As Duroc’s biographer Danielle Meyrueix notes, when writing of his wife and child he habitually referred to “her son” rather than “our son”. Perhaps not the most engaged of fathers.) Napoléon died on 6 May 1812 at Maidières in Lorraine. The architect Pierre Fontaine, noting in his journal that Hervas had asked him to design a tomb for her lost son, wrote that the child had been “a few days older than the King of Rome and destined to enjoy at that prince’s side all the favor with which the Emperor honored his father.”

Their daughter Hortense Eugénie Nieves Duroc was born on 14 May 1812, eight days after the young Napoléon’s death. (In a letter, Duroc implied that the news of the boy’s death had been kept from Hervas, who was in Paris, to avoid imperiling her health.) Named for her godmother, Hortense de Beauharnais, she was baptized in January 1813 alongside the duke of Bassano's daughter. After Duroc’s death in May 1813, Napoleon transferred the duchy of Friuli to her, writing to Hervas that Hortense would be “assured of my constant protection”. He also remembered her in his will, leaving her a large sum of money and recommending, in one last attempt at matchmaking, that she marry Bessières’s son, the duke of Istria. Hortense’s aunt wrote in 1823 that “Hortense is perfectly sweet, she’s a rare child for her spirit and intelligence, who her poor father would have been happy to see so fine in all respects”. She died of pneumonia on 24 September 1829 after three days of illness, aged seventeen.

A 1933 biography of Charles-Nicolas Fabvier (Hervas’s second husband) identifies this painting by Jeanne-Elisabeth Chaudet as a young Hortense Duroc. It was sold at an auction a few years ago with the title “Young Embroideress”, so either the sitter’s identity has been lost since then or it may never have been Hortense at all.

Duroc’s long liaison with the dancer Emilie Bigottini may also have resulted in at least one child. Felix Bouvier, writing a biographical sketch of Bigottini in 1909, claimed that “children were born of this irregular union, a daughter and a son named Odilon”. However, Odilon (full name Pierre Dominique Jean Marie Odilon Michel du Roc), born in 1801, was the son of Duroc’s cousin Géraud Pierre Michel du Roc, the marquis de Brion. On Duroc’s death, Napoleon made Odilon a page in the imperial household. (This may have given rise to Bouvier’s claim, as it seems to have confused people at the time. Caulaincourt had been tasked with sorting out Duroc’s affairs, including a substantial amount of money for Bigottini, and Duroc’s sister Jeanne implied that he had gotten the wrong impression from one of Duroc’s requests: “On the subject of the allowance for little Odilon, M. the duke of Vicenza was misled…he took a step which pained me very much”.) As for the daughter, all I’ve been able to find so far is a remark from Laure Junot that “It was known that the count Armand de Fuentès had had a daughter with Mademoiselle Bigottini, and that Duroc was in the same position”.

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

Notable Philhellenes

Hundreds of Greek volunteers took part in the struggle of the Greeks and stood by their side in all the critical moments of the Revolution. Many of them have made history internationally.

The first steamship in history to take part in military operations, was the Karteria of the Greek fleet, commanded by the great British Philhellene Frank Abney Hastings (1794 – 1828), who had even financed its weapons. The most important success of Hastings and Karteria was in the Battle of Agali (Itea Bay) on September 17, 1827, where Karteria sank alone the Turkish flagship and destroyed 9 enemy ships.

Portrait of the great British Philhellene Frank Abney Hastings (1794 – 1828), created by the German Philhellene Karl Krazeisen (1794-1878)

Philhellenes helped rescue and release a large number of slaves after the end of the Revolution. They reflected the slaves’ drama trough Western art in many ways.

Painting by German painter and philhellene Paul Emil Jacobs (1802 – 1866), a scene from the trade of Greek slaves.

The Philhellenic movement made its presence felt throughout the 19th and even 20th centuries, and its contribution was critical and decisive for the liberation of Greece.

Many Philhellenes of the period 1821 returned to Greece when their assistance was needed it again.

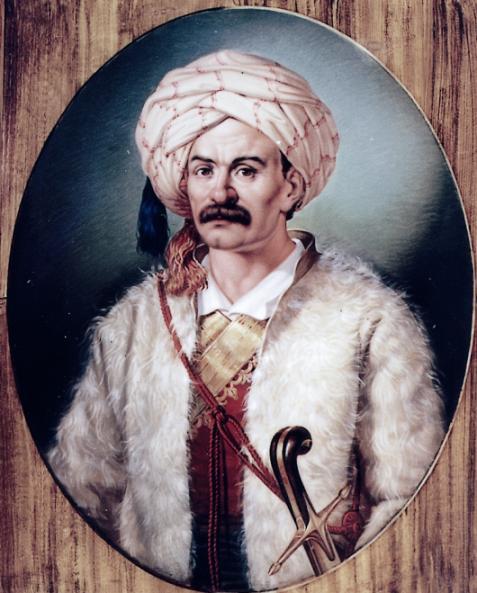

Charles Nicolas Fabvier (1783-1855) was a French philhellene general and commander of the regular army of Greece during the Greek Revolution of 1821. He is considered the most capable and most beloved of all philhellene officers.

The great American Philhellene doctor and philanthropist Dr Samuel Howe, was one of them. He came to Greece for the second time in 1866-67 bringing aid for refugees from Crete during the Cretan Revolution.

Cretan knife 19th century, gift of the Cretans to the American philhellene Dr. Samuel Howe

Philhellenism continued to manifest itself throughout the 19th century, but also into the 20th. For example, in the unsuccessful Greek-Turkish War of 1897, the Italian Philhellene Ricciotti Garibaldi, the leader of a Corps of Garibaldi red-tunics, fought bravely.

This Corps returned to Greece and fought again on the side of the Greeks also during the victorious war of 1912-1913, which liberated Greece.

Sword donated by the French to the Italian Ricciotti Garibaldi, when he fought on the French side in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-1871

In 1897, the British composer and Philhellene Clement Harris came to Greece, he fought heroically and died for the independence of Greece in the Greek-Turkish war of 1897 in the Five Wells in Arta. He was buried in the Anglican Church of St. Paul in Athens.

A handwritten letter from a relative of Clement Harris to his friends in England, informing them that he was “killed in the Five Wells on April 23, 1897, fighting for the rights of Greece”

The oath of Lord Byron next to the tomb of Markos Botsaris in Messolonghi, painting by a follower of the Italian painter Lodovico Lipparini (1802 – 1856), oil on wood, 19th century

Philellenism remains to this day an important cultural, political, social, philosophical and literary movement. It inspires educational and academic programs in all modern societies, and the values on which it is based are the cornerstones of the civilized world.

The trip to Greece and the pilgrimage to the Acropolis of Athens and the other emblematic archeological sites throughout Greece, cause to every free man of today the same feelings as those they caused to Lord Byron 200 years ago.

Info by the Society for Hellenism and Philhellenism

#thank you dear xenoi <3#Clement Harris was YOUNG damn :'(#those people deserve recognition for their help and i thought I'd make a post about them right after the anniversary of the independence#Philhellenes#greek history#Philellenism

39 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Charles Nicolas Baron Fabvier (1783–1855), French soldier and volunteer in War of Greek Independence, Pierre Jean David d'Angers, 1828, Metropolitan Museum of Art: European Sculpture and Decorative Arts

Gift of Samuel P. Avery, 1898

Size: Diameter: 5 7/8 in. (14.9 cm)

Medium: Bronze, cast - single

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/188415

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Charles Nicolas Baron Fabvier (1783–1855), French soldier and volunteer in War of Greek Independence by Pierre Jean David d'Angers, European Sculpture and Decorative Arts

Medium: Bronze, cast - single

Gift of Samuel P. Avery, 1898 Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY

http://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/188415

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Nauplie : Monument aux Français ayant participe a la Guerre d’Indépendance Héllénique (rate lors des 2 premières visites!): Marechal Nicolas-Joseph MAISON, General Charles Nicolas FABVIER, Amiral Henri de VIGNY. #nauplie #guerredindependancegrecque #nicolasmaison #fabvier #derigny #moreaexpedition #grece #instapic #photooftheday #ilovegreece #discovergreece (à Kipos Nafplio) https://www.instagram.com/p/B2t7uCJiuun/?igshid=zubp6wxheiup

#nauplie#guerredindependancegrecque#nicolasmaison#fabvier#derigny#moreaexpedition#grece#instapic#photooftheday#ilovegreece#discovergreece

0 notes

Photo

Time for a post about my favorite improbable romance of the Napoleonic era!

Maria de las Nieves Dominique Antoinette Rita Josèphe Louise Catherine Martinez de Hervas was barely fourteen when she married Géraud Christophe Michel Duroc in 1802. The daughter of a Spanish banker and diplomat, she had been educated at Madame Campan’s school along with Hortense de Beauharnais, Caroline Bonaparte, and several other young women who would go on to marry marshals or generals.

While not the outright disaster that some of the other marriages that Napoleon arranged were, the couple’s relationship seems to have been distant. Duroc stayed in Paris, busy with his duties as Grand Marshal, while Hervas spent much of her time at the château de Clémery, outside Duroc’s hometown of Pont-à-Mousson in Lorraine, accompanied by her sister-in-law Jeanne Magdeleine Duroc. It was there that she met Charles Nicolas Fabvier in 1805.

Also a native of Pont-à-Mousson, Fabvier was a decade younger than Duroc; after studying at the École polytechnique, he had joined the Grande Armée as an artillery officer in 1804. What Hervas initially thought of Fabvier, we don’t know; he became a family friend, though that may have been Duroc taking an interest in a fellow officer from Pont-à-Mousson. Fabvier, however, fell hopelessly in love with Hervas.

Writing to his brother Nicolas in 1808 from Constantinople, where he had accompanied a diplomatic mission, Fabvier reflected on the intensity of his feelings: “I’m afraid it’s a disease. In the midst of my labors, while crossing the desert, on horseback, I always find her in the same place, face to face with me...”

In another letter to his brother, he continued: “I have such a veneration, such a high opinion of her that I don’t dare speak of it without permission. If you could only see, if she knew that throughout three years’ absence I thought of her every instant!...But what’s the use? She is a princess now; would she still recognize an unhappy knight, even by name? In short, that woman never leaves my thoughts, let alone my heart. May God bless her and bring her happiness.”

After returning from Constantinople, Fabvier became Marmont’s aide de camp in 1811, and fought in the Peninsular War. He rode the entire length of Europe in the summer of 1812 to bring Napoleon news of Marmont’s defeat at Salamanca, arriving on the eve of the battle of Borodino.

His long absences from France did nothing to dull his feelings for Hervas. After visiting her in Paris in the spring of 1813, he wrote to his brother, who must have had the patience of a saint: “Her presence illuminates, her approach warms; she passes by and one is content; she pauses and one is happy; to regard her is to live; she is dawn in human form; she does nothing else but be there, that suffices, she Edenizes the house, she exudes a paradise.”

As Marmont’s aide-de-camp, Fabvier took part in the campaign of 1813 in central Europe, which meant that he was present for Duroc’s death that May. Having visited the dying man once to say goodbye—”He recognized me,” he told Nicolas, “[and] bade me farewell with kindness and calm”—he returned again later that night, spending hours at Duroc’s side. He wrote to his brother a few days later: “I can’t describe to you all the grievous pains that overwhelmed me while, sitting on a bench and without him seeing me, I watched the man who had been so happy until now…I wanted to speak to him, to help him to move. I never dared.” In his journal, he was more frank about the conflicting feelings produced by seeing his beloved Hervas’s husband mortally wounded: “I fended off, or rather I avoided having, those [thoughts] that I should not have had. I owe myself this fairness. But Nives [sic], if you weep for him, why did I not die for him!”

Later, he added: “Strange fortune! Do you show me the possibility to make me feel my unhappiness all the more keenly? Her rank. Her family. The Emperor. Such obstacles that I'll never overcome…” He worried about the effect the news would have on Hervas, who had already suffered the death of her fifteen-month-old son in 1812. He told Nicolas not to mention him to her in case that would remind her of Duroc—”unless you’re asked whether I wish I could have taken the unlucky bullet; reply: yes”.

After Napoleon’s downfall, Fabvier spent much of the early 1820s getting arrested on suspicion of being involved in Bonapartist plots to overthrow the government. In 1823, after being acquitted for a second time due to lack of evidence, he left France for Greece, where he became a hero in the War of Independence. Hervas remained at Clémery, raising her young daughter Hortense, and was eventually granted a pension by Charles X. When Fabvier returned to France in the late 1820s, he found Hervas still greatly affected by the losses she had suffered, and wrote to his brother (as always) that he “trembled lest fortune send that unfortunate woman yet another horrible blow”.

His words proved prophetic: Hortense Duroc died of pneumonia in September 1829, aged just seventeen. Hervas was so overwhelmed by Hortense’s death that doctors feared for her life; ordered to travel abroad for her health, she went to Italy, accompanied by Fabvier. They visited Hortense de Beauharnais, who was living in Switzerland, and returned to France shortly before the July Revolution.

Twenty-six years after they’d first met, Hervas and Fabvier were married in Paris on May 16, 1831. Their son, Louis Charles Eugène, was born in December of that year.

Fabvier had his happy ending at last; it’s less clear what Hervas felt. Passages from Fabvier’s letters and journal survive in a pair of early twentieth-century biographies, but none of Hervas’s writing, letters or otherwise, is publicly available. Perhaps she shared Fabvier’s feelings; perhaps, after the devastating death of her daughter, she simply wanted stability. Regardless of how she felt about Fabvier, Hervas seems to have considered Hortense’s death, as well as the death of her first son, the defining events of her life. When she died in December 1871, having outlived her second husband by sixteen years, she left money for a funeral monument with the inscription “To the unhappiest of mothers”.

Images: “La baronne Fabvier,” in W. Sérieyx, Un géant de l’action: le général Fabvier (1933), which gives no information about the artist or date. “Charles Fabvier (1782-1855)”, artist unknown, The War Museum, Athens, Greece.

#this post is a mess but fabvier's letters are just So Much that i wanted to share them#maria de las nieves martinez de hervas#charles nicolas fabvier#duroc#napoleonic wars

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Charles-Nicolas Fabvier, a French artillery officer, was attached to Napoleon’s diplomatic embassy to Persia between 1807 and 1809. On his way from Constantinople to Tehran in late 1807, he passed through the city of Tokat:

I had sent my caravan off a quarter of an hour ago and was walking across the bazaar with my postilion, when I heard someone behind me crying, “Citizen! Citizen!” I turned my head and saw a fairly well-dressed Turk running towards me. He seized me by the hand and asked me with great urgency, “How fares the Republic?” “The Republic,” I said to him, “made a marriage that has not turned out well for her.” This man bade me enter his shop; he was a tobacco merchant. Smoking a pipe, he recounted to me that he had been taken prisoner in Egypt; brought through so many countries, with so much fatigue and misery, he made himself into a Turk, got married and established himself well enough that he no longer wished for an alteration.

(Quoted in Antonin Debidour, Le général Fabvier: sa vie militaire et politique, 1904)

#this poor guy. imagine the first news you hear from france in years being... that.#charles nicolas fabvier#napoleonic wars

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

When will someone write a 500-page romance novel about Charles Nicolas Fabvier and Marie Nieves Martinez de Hervas... They deserve it.

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

I was flipping through W. Sérieyx‘s biography of Charles-Nicolas Fabvier earlier even though I have no idea when I’ll have time to read it, and came across this portrait of baby Hortense Duroc in 1814.

#there's a painting of her! there's a painting of her!#i'm having an emotion#i'm also side-eyeing the date a bit because embroidery sure is a lot of fine motor control for a two-year-old but w/e#duroc#endless research hell

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Charles Fabvier to his brother Nicolas, 23 May 1813:

Oh my friend, what a horrible blow! The unhappy Duke of Friuli [Duroc] was struck by a cannonball in an insignificant skirmish. As soon as I heard--I was at the outposts--I went to him; I was beside myself. He recognized me, bade me farewell with kindness and calm. With what firmness he suffered the cruelest pains! I returned to him that night; I’m going to go back again. But it’s only to see the martyr suffer, because there’s no more hope, his intestines are cut...What desolation! I don’t dare think of it. I fear a similar unhappiness for his whole family. Dismay is everywhere in the army. Everyone loved him. I leave you in order to go to him again. I would perhaps do better not to go to him; it’s a harrowing spectacle. The pain is sometimes so sharp that it wrings from him cries that wound me.

And to his brother on 1 June:

I can’t describe for you the painful sorrow that overwhelmed me when, sitting on a bench and without him seeing me, I watched that man who had been so happy until now: he was there, laid in the straw, ready to leave it all, to lose every favor that heaven could have granted to a man on earth. Maybe heaven thought that the happiness was too great for him to enjoy it for long. For more than six hours, I voluntarily burdened myself with that sad spectacle. The first time that I came in, he bade me farewell with calm and an air of friendship more agreeable than he had ever shown me; after that, a hundred times, while that unhappy man complained of the terrible pains that wracked him, I wanted to speak to him, to help him move. I never dared. My marshal [Marmont] came to see him; I brought him there; they said goodbyes that would have wrung tears from anyone. That night, in a moment of delirium, he complained of having no one to support his arm. I was behind him; I held him up without him seeing me. The army marched on. I went back again as soon as I could: he was dead. He had suffered for at least thirty hours. But he had been happy for many years...

Source: A. Debidour, Le général Fabvier: sa vie militaire et politique (Paris: Plon, 1904), 63-64.

19 notes

·

View notes