#could have led to USEFUL MEDICAL DATA??? with that logic if i started digging up graves to poke at brains

Text

So after finishing the behind the bastards episodes of Mengele I have learned I was right Nazis were Very Bad at medical science and we didn't learn pretty much dick shit all, and next time someone tells me Nazis taught us a TON about modern medical science I'm going to start quizzing them on what they know about scientific methodologies and if they think any given Nazi could have met the most basic requirements of performing research. And if the answer is anything other than no, I know to dismiss their opinions on anything to do with that.

#winters ramblings#like yall seriously telling ME you think. studies done on starving overworked people whom their captors assumed they were superior to#gathered USEFUL medical data on those same people they thought of as less than human?? youre telling me you think THAT set of circumstances#could have led to USEFUL MEDICAL DATA??? with that logic if i started digging up graves to poke at brains#id be a talented neurologist instead of a grave robbing piece of shit doing fucked up experiments 🙄🙄🙄

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

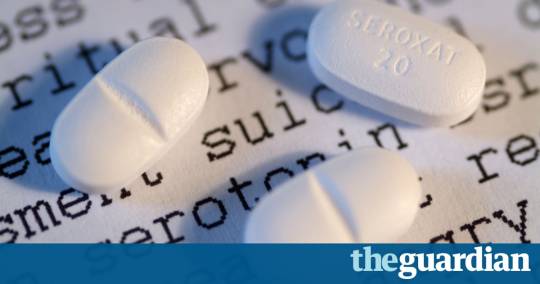

Is everything you think you know about depression wrong?

In this extract from his new book, Johann Hari, who took antidepressants for 14 years, calls for a new approach

In the 1970s, a truth was accidentally discovered about depression one that was quickly swept aside, because its implications were too inconvenient, and too explosive. American psychiatrists had produced a book that would lay out, in detail, all the symptoms of different mental illnesses, so they could be identified and treated in the same way across the United States. It was called the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual. In the latest edition, they laid out nine symptoms that a patient has to show to be diagnosed with depression like, for example, decreased interest in pleasure or persistent low mood. For a doctor to conclude you were depressed, you had to show five of these symptoms over several weeks.

The manual was sent out to doctors across the US and they began to use it to diagnose people. However, after a while they came back to the authors and pointed out something that was bothering them. If they followed this guide, they had to diagnose every grieving person who came to them as depressed and start giving them medical treatment. If you lose someone, it turns out that these symptoms will come to you automatically. So, the doctors wanted to know, are we supposed to start drugging all the bereaved people in America?

The authors conferred, and they decided that there would be a special clause added to the list of symptoms of depression. None of this applies, they said, if you have lost somebody you love in the past year. In that situation, all these symptoms are natural, and not a disorder. It was called the grief exception, and it seemed to resolve the problem.

Then, as the years and decades passed, doctors on the frontline started to come back with another question. All over the world, they were being encouraged to tell patients that depression is, in fact, just the result of a spontaneous chemical imbalance in your brain it is produced by low serotonin, or a natural lack of some other chemical. Its not caused by your life its caused by your broken brain. Some of the doctors began to ask how this fitted with the grief exception. If you agree that the symptoms of depression are a logical and understandable response to one set of life circumstances losing a loved one might they not be an understandable response to other situations? What about if you lose your job? What if you are stuck in a job that you hate for the next 40 years? What about if you are alone and friendless?

The grief exception seemed to have blasted a hole in the claim that the causes of depression are sealed away in your skull. It suggested that there are causes out here, in the world, and they needed to be investigated and solved there. This was a debate that mainstream psychiatry (with some exceptions) did not want to have. So, they responded in a simple way by whittling away the grief exception. With each new edition of the manual they reduced the period of grief that you were allowed before being labelled mentally ill down to a few months and then, finally, to nothing at all. Now, if your baby dies at 10am, your doctor can diagnose you with a mental illness at 10.01am and start drugging you straight away.

Dr Joanne Cacciatore, of Arizona State University, became a leading expert on the grief exception after her own baby, Cheyenne, died during childbirth. She had seen many grieving people being told that they were mentally ill for showing distress. She told me this debate reveals a key problem with how we talk about depression, anxiety and other forms of suffering: we dont, she said, consider context. We act like human distress can be assessed solely on a checklist that can be separated out from our lives, and labelled as brain diseases. If we started to take peoples actual lives into account when we treat depression and anxiety, Joanne explained, it would require an entire system overhaul. She told me that when you have a person with extreme human distress, [we need to] stop treating the symptoms. The symptoms are a messenger of a deeper problem. Lets get to the deeper problem.

*****

I was a teenager when I swallowed my first antidepressant. I was standing in the weak English sunshine, outside a pharmacy in a shopping centre in London. The tablet was white and small, and as I swallowed, it felt like a chemical kiss. That morning I had gone to see my doctor and I had told him crouched, embarrassed that pain was leaking out of me uncontrollably, like a bad smell, and I had felt this way for several years. In reply, he told me a story. There is a chemical called serotonin that makes people feel good, he said, and some people are naturally lacking it in their brains. You are clearly one of those people. There are now, thankfully, new drugs that will restore your serotonin level to that of a normal person. Take them, and you will be well. At last, I understood what had been happening to me, and why.

However, a few months into my drugging, something odd happened. The pain started to seep through again. Before long, I felt as bad as I had at the start. I went back to my doctor, and he told me that I was clearly on too low a dose. And so, 20 milligrams became 30 milligrams; the white pill became blue. I felt better for several months. And then the pain came back through once more. My dose kept being jacked up, until I was on 80mg, where it stayed for many years, with only a few short breaks. And still the pain broke back through.

I started to research my book, Lost Connections: Uncovering The Real Causes of Depression and the Unexpected Solutions, because I was puzzled by two mysteries. Why was I still depressed when I was doing everything I had been told to do? I had identified the low serotonin in my brain, and I was boosting my serotonin levels yet I still felt awful. But there was a deeper mystery still. Why were so many other people across the western world feeling like me? Around one in five US adults are taking at least one drug for a psychiatric problem. In Britain, antidepressant prescriptions have doubled in a decade, to the point where now one in 11 of us drug ourselves to deal with these feelings. What has been causing depression and its twin, anxiety, to spiral in this way? I began to ask myself: could it really be that in our separate heads, all of us had brain chemistries that were spontaneously malfunctioning at the same time?

To find the answers, I ended up going on a 40,000-mile journey across the world and back. I talked to the leading social scientists investigating these questions, and to people who have been overcoming depression in unexpected ways from an Amish village in Indiana, to a Brazilian city that banned advertising and a laboratory in Baltimore conducting a startling wave of experiments. From these people, I learned the best scientific evidence about what really causes depression and anxiety. They taught me that it is not what we have been told it is up to now. I found there is evidence that seven specific factors in the way we are living today are causing depression and anxiety to rise alongside two real biological factors (such as your genes) that can combine with these forces to make it worse.

Once I learned this, I was able to see that a very different set of solutions to my depression and to our depression had been waiting for me all along.

To understand this different way of thinking, though, I had to first investigate the old story, the one that had given me so much relief at first. Professor Irving Kirsch at Harvard University is the Sherlock Holmes of chemical antidepressants the man who has scrutinised the evidence about giving drugs to depressed and anxious people most closely in the world. In the 1990s, he prescribed chemical antidepressants to his patients with confidence. He knew the published scientific evidence, and it was clear: it showed that 70% of people who took them got significantly better. He began to investigate this further, and put in a freedom of information request to get the data that the drug companies had been privately gathering into these drugs. He was confident that he would find all sorts of other positive effects but then he bumped into something peculiar.

Illustration by Michael Driver.

We all know that when you take selfies, you take 30 pictures, throw away the 29 where you look bleary-eyed or double-chinned, and pick out the best one to be your Tinder profile picture. It turned out that the drug companies who fund almost all the research into these drugs were taking this approach to studying chemical antidepressants. They would fund huge numbers of studies, throw away all the ones that suggested the drugs had very limited effects, and then only release the ones that showed success. To give one example: in one trial, the drug was given to 245 patients, but the drug company published the results for only 27 of them. Those 27 patients happened to be the ones the drug seemed to work for. Suddenly, Professor Kirsch realised that the 70% figure couldnt be right.

It turns out that between 65 and 80% of people on antidepressants are depressed again within a year. I had thought that I was freakish for remaining depressed while on these drugs. In fact, Kirsch explained to me in Massachusetts, I was totally typical. These drugs are having a positive effect for some people but they clearly cant be the main solution for the majority of us, because were still depressed even when we take them. At the moment, we offer depressed people a menu with only one option on it. I certainly dont want to take anything off the menu but I realised, as I spent time with him, that we would have to expand the menu.

This led Professor Kirsch to ask a more basic question, one he was surprised to be asking. How do we know depression is even caused by low serotonin at all? When he began to dig, it turned out that the evidence was strikingly shaky. Professor Andrew Scull of Princeton, writing in the Lancet, explained that attributing depression to spontaneously low serotonin is deeply misleading and unscientific. Dr David Healy told me: There was never any basis for it, ever. It was just marketing copy.

I didnt want to hear this. Once you settle into a story about your pain, you are extremely reluctant to challenge it. It was like a leash I had put on my distress to keep it under some control. I feared that if I messed with the story I had lived with for so long, the pain would run wild, like an unchained animal. Yet the scientific evidence was showing me something clear, and I couldnt ignore it.

*****

So, what is really going on? When I interviewed social scientists all over the world from So Paulo to Sydney, from Los Angeles to London I started to see an unexpected picture emerge. We all know that every human being has basic physical needs: for food, for water, for shelter, for clean air. It turns out that, in the same way, all humans have certain basic psychological needs. We need to feel we belong. We need to feel valued. We need to feel were good at something. We need to feel we have a secure future. And there is growing evidence that our culture isnt meeting those psychological needs for many perhaps most people. I kept learning that, in very different ways, we have become disconnected from things we really need, and this deep disconnection is driving this epidemic of depression and anxiety all around us.

Lets look at one of those causes, and one of the solutions we can begin to see if we understand it differently. There is strong evidence that human beings need to feel their lives are meaningful that they are doing something with purpose that makes a difference. Its a natural psychological need. But between 2011 and 2012, the polling company Gallup conducted the most detailed study ever carried out of how people feel about the thing we spend most of our waking lives doing our paid work. They found that 13% of people say they are engaged in their work they find it meaningful and look forward to it. Some 63% say they are not engaged, which is defined as sleepwalking through their workday. And 24% are actively disengaged: they hate it.

Antidepressant prescriptions have doubled over the last decade. Photograph: Anthony Devlin/PA

Most of the depressed and anxious people I know, I realised, are in the 87% who dont like their work. I started to dig around to see if there is any evidence that this might be related to depression. It turned out that a breakthrough had been made in answering this question in the 1970s, by an Australian scientist called Michael Marmot. He wanted to investigate what causes stress in the workplace and believed hed found the perfect lab in which to discover the answer: the British civil service, based in Whitehall. This small army of bureaucrats was divided into 19 different layers, from the permanent secretary at the top, down to the typists. What he wanted to know, at first, was: whos more likely to have a stress-related heart attack the big boss at the top, or somebody below him?

Everybody told him: youre wasting your time. Obviously, the boss is going to be more stressed because hes got more responsibility. But when Marmot published his results, he revealed the truth to be the exact opposite. The lower an employee ranked in the hierarchy, the higher their stress levels and likelihood of having a heart attack. Now he wanted to know: why?

And thats when, after two more years studying civil servants, he discovered the biggest factor. It turns out if you have no control over your work, you are far more likely to become stressed and, crucially, depressed. Humans have an innate need to feel that what we are doing, day-to-day, is meaningful. When you are controlled, you cant create meaning out of your work.

Suddenly, the depression of many of my friends, even those in fancy jobs who spend most of their waking hours feeling controlled and unappreciated started to look not like a problem with their brains, but a problem with their environments. There are, I discovered, many causes of depression like this. However, my journey was not simply about finding the reasons why we feel so bad. The core was about finding out how we can feel better how we can find real and lasting antidepressants that work for most of us, beyond only the packs of pills we have been offered as often the sole item on the menu for the depressed and anxious. I kept thinking about what Dr Cacciatore had taught me we have to deal with the deeper problems that are causing all this distress.

I found the beginnings of an answer to the epidemic of meaningless work in Baltimore. Meredith Mitchell used to wake up every morning with her heart racing with anxiety. She dreaded her office job. So she took a bold step one that lots of people thought was crazy. Her husband, Josh, and their friends had worked for years in a bike store, where they were ordered around and constantly felt insecure, Most of them were depressed. One day, they decided to set up their own bike store, but they wanted to run it differently. Instead of having one guy at the top giving orders, they would run it as a democratic co-operative. This meant they would make decisions collectively, they would share out the best and worst jobs and they would all, together, be the boss. It would be like a busy democratic tribe. When I went to their store Baltimore Bicycle Works the staff explained how, in this different environment, their persistent depression and anxiety had largely lifted.

Its not that their individual tasks had changed much. They fixed bikes before; they fix bikes now. But they had dealt with the unmet psychological needs that were making them feel so bad by giving themselves autonomy and control over their work. Josh had seen for himself that depressions are very often, as he put it, rational reactions to the situation, not some kind of biological break. He told me there is no need to run businesses anywhere in the old humiliating, depressing way we could move together, as a culture, to workers controlling their own workplaces.

*****

With each of the nine causes of depression and anxiety I learned about, I kept being taught startling facts and arguments like this that forced me to think differently. Professor John Cacioppo of Chicago University taught me that being acutely lonely is as stressful as being punched in the face by a stranger and massively increases your risk of depression. Dr Vincent Felitti in San Diego showed me that surviving severe childhood trauma makes you 3,100% more likely to attempt suicide as an adult. Professor Michael Chandler in Vancouver explained to me that if a community feels it has no control over the big decisions affecting it, the suicide rate will shoot up.

This new evidence forces us to seek out a very different kind of solution to our despair crisis. One person in particular helped me to unlock how to think about this. In the early days of the 21st century, a South African psychiatrist named Derek Summerfeld went to Cambodia, at a time when antidepressants were first being introduced there. He began to explain the concept to the doctors he met. They listened patiently and then told him they didnt need these new antidepressants, because they already had anti-depressants that work. He assumed they were talking about some kind of herbal remedy.

He asked them to explain, and they told him about a rice farmer they knew whose left leg was blown off by a landmine. He was fitted with a new limb, but he felt constantly anxious about the future, and was filled with despair. The doctors sat with him, and talked through his troubles. They realised that even with his new artificial limb, his old jobworking in the rice paddieswas leaving him constantly stressed and in physical pain, and that was making him want to just stop living. So they had an idea. They believed that if he became a dairy farmer, he could live differently. So they bought him a cow. In the months and years that followed, his life changed. His depressionwhich had been profoundwent away. You see, doctor, they told him, the cow was an antidepressant.

To them, finding an antidepressant didnt mean finding a way to change your brain chemistry. It meant finding a way to solve the problem that was causing the depression in the first place. We can do the same. Some of these solutions are things we can do as individuals, in our private lives. Some require bigger social shifts, which we can only achieve together, as citizens. But all of them require us to change our understanding of what depression and anxiety really are.

This is radical, but it is not, I discovered, a maverick position. In its official statement for World Health Day in 2017, the United Nations reviewed the best evidence and concluded that the dominant biomedical narrative of depression is based on biased and selective use of research outcomes that must be abandoned. We need to move from focusing on chemical imbalances, they said, to focusing more on power imbalances.

After I learned all this, and what it means for us all, I started to long for the power to go back in time and speak to my teenage self on the day he was told a story about his depression that was going to send him off in the wrong direction for so many years. I wanted to tell him: This pain you are feeling is not a pathology. Its not crazy. It is a signal that your natural psychological needs are not being met. It is a form of grief for yourself, and for the culture you live in going so wrong. I know how much it hurts. I know how deeply it cuts you. But you need to listen to this signal. We all need to listen to the people around us sending out this signal. It is telling you what is going wrong. It is telling you that you need to be connected in so many deep and stirring ways that you arent yet but you can be, one day.

If you are depressed and anxious, you are not a machine with malfunctioning parts. You are a human being with unmet needs. The only real way out of our epidemic of despair is for all of us, together, to begin to meet those human needs for deep connection, to the things that really matter in life.

This is an edited extract from Lost Connections: Uncovering the Real Causes of Depression and the Unexpected Solutions by Johann Hari, published by Bloomsbury on 11 January (16.99). To order a copy for 14.44 go to guardianbookshop.com or call 0330 333 6846. Free UK p&p over 10, online orders only. Phone orders min p&p of 1.99. It will be available in audio at audible.co.uk

Read more: https://www.theguardian.com/society/2018/jan/07/is-everything-you-think-you-know-about-depression-wrong-johann-hari-lost-connections

from Viral News HQ http://ift.tt/2nZt0Li

via Viral News HQ

0 notes

Text

FICTION: Immutable

By: Leon Lee

I remember being told that I was a perfectly normal child, or at least, that’s what the doctors said.

Average in all respects from the time I was born, although there was one who’d said differently.

Being the people that they were, my mom and dad had heard the man out, but hadn’t really listened. To them, he was one dissenter among a crowd of trained doctors who said otherwise, and they took me home as soon as they were able to.

That was what they told me, anyway.

They asked a lot of questions when I brought it up, and they seemed pretty shocked. Kids generally didn’t remember things from that far back, but I remembered a few things clearly.

A lot of non-sequiturs, but the main thing I remembered was a calm, measured voice. My parents said it might have been one of the doctors in the hospital, and that I could have developed some memories in the womb.

They might have said I was a normal kid, but I really wasn’t that normal in the head.

I wondered why they hadn’t believed that doctor. Still, I assumed they had their reasons, and I never bothered to question it.

At least, not until I turned thirteen.

If I’m honest with myself, I still can’t remember how it happened. It was a regular day, I know that much, but I ended up injuring my hand somehow.

Naturally, my parents freaked. It bled a lot for a small cut, and they kept asking me questions.

“Are you okay?! Does it hurt?” That, among all sorts of other things. I insisted I was fine, but they kept fussing over it, even though I’m older now, and damn it, I could take care of myself.

Guess that’s the downside of protective parents.

That was when I first thought something might be up, since I hadn’t felt the injury. Still, I hadn’t thought it was a big deal. Just a high pain tolerance, maybe?

Never mind the fact that I’d never been injured before, and probably couldn’t have any kind of tolerance for pain as a result. That was perfectly logical in my head back then.

The next time I got injured, I was fifteen, and working with chemicals in the school’s science lab during class.

Some moron heated their beaker too much during the experiment, and the glass shattered everywhere. Well, more like exploded everywhere, but I’ll try and be nice.

The people closest to the explosion took the worst of it, as you’d expect, but I wasn’t too far away myself. I didn’t feel anything though, so I assumed I was fine even as we rushed them to the nurse and called the hospital for the more serious glass wounds.

So when people started crowding around me, prodding me and checking my pulse and heartbeat, I got pretty confused.

“What’s going on?” I asked the nurse. In response, she pointed downward, and I folloe to find a long shard of glass poking through my left side.

It had gone clean through the lab coat I wore, and I just stared. There wasn’t much blood, but the sight of it was fairly shocking.

I was still stunned when they pulled me into an ambulance and rushed me to the hospital in case it had pierced anything important, like my liver or gut.

I don’t remember much of the details of what they did, but I remember one thing clearly. They kept asking me if I was in much pain, if I felt anything wrong and how bad the pain was.

My answer shocked them pretty badly. “I don’t feel anything. It doesn’t hurt at all.”

Judging by the way they acted afterwards, I think they assumed I was dying. Oxygen mask, brain scans, people poking around the gash in my side, the works.

Eventually, they had to admit I was fine, besides the fact that I was weaker than usual from blood loss and surgery to remove the glass splinters.

That was when I learned that actually, something was actually pretty wrong with me.

—————————————————————————————————————————

“Congenital analgesia,” they told me, having checked with experts and others to confirm their suspicions.

It’s rare, and only about one in a million people are born with it in the world. Lucky me.

Anyway, what it does is simple: I can’t feel pain. Not at all. Doesn’t affect the rest of my senses at all. Sounds great, doesn’t it?

Well, it isn’t.

It means that I can’t tell if I’m injured or not, or what hurts me.

The doctors were amazed that it wasn’t discovered earlier, since most discover it when their kid starts teething, since they chew their own fingers and tongue and can’t feel the pain even when they start breaking the skin.

Of course, me being me, my child self had never apparently felt the need to chew on myself while I was teething. My parents had sheltered me enough so that I’d never been significantly injured, but that didn’t change the matter.

They told me I had to learn to be vigilant, because if I wasn’t, this could easily happen again, and even though I can’t feel the pain, I’d feel the effects of whatever was causing it soon enough.

That was probably the hardest thing I’ve ever had to do.

I like to think of myself as a free-spirited person. I’ve never really been good about abiding by strict rules and guidelines, and I remember taking the opportunity to escape them whenever I could.

I liked to live by my own rules, which thankfully didn’t translate into a disrespect for authority, and just showed itself in my unfettered attitude and approach to life.

What they told me I had to do was give all of that up, and I remember having a hard time accepting it at first. My parents were especially horrified by it, and refused to let me out of their sight for a while.

I didn’t take that well either.

I didn’t want to have to change my life for fear of something that hadn’t been an issue until now.

I was stubborn and foolish and ignorant, and it took a return trip to the hospital for a shattered shoulder before I accepted what they were telling me.

I started holding myself back from what I would normally do. Exercised some restraint for once to counter my own nature.

I was careful and watchful and a million other things that I just wasn’t, and I hated it.

And then, a year later, I heard that there was a potential cure in the works. Could you really blame me for having jumped at the news?

I started looking into it, and found out that one of the people involved in the project had their offices fairly close to me.

Doctor M.G. Jones, reputed therapist and doctor, specialises in birth disorders and defects.

I made an appointment as soon as I could, and on a cold Wednesday in March, I walked into his office and knocked on the door of his consultation room.

I heard a chair scrape against the floor, and then the door was opened by a man in a ruffled suit.

He scanned me briefly, and I caught a faint glimmer in his eye before he spoke. “Ah, I’ve been expecting you. Please, come in.”

I complied, and found to my surprise that his office was…...well, not an office. It was more like a casual room, with sofas, a coffee table and warm, gentle lighting. There was the obligatory messy desk, of course, but otherwise, it was nice.

I must have looked just as surprised as I thought I was, because the doctor grinned at me as he closed the door and moved beside his desk.

“Not exactly what you were expecting, is it?”

“No,” I answered truthfully. “I thought it would be a lot more clinical.”

He chuckled. “Most people think that way, but generally, I’m not that kind of doctor. Sometimes I am, but that’s for a different time and a different place.”

He settled himself in a padded oak chair behind the desk. “So, what I can do for you today?”

“I-” I stopped. Something was bothering me.

Something about the glimmer in his eye when he’d looked me over.

One of the first things I’d done when adapting to my condition was learn to be vigilant. For better or for worse, that included being vigilant of other people, and it was a skill I put to use now.

I looked at his eyes and his hair and his face, noticing the brown, slightly greying strands and the slight frown he was wearing as he noticed my confused expression.

“Is something wrong?” he asked, and my attention turned to his voice, and the manner he spoke in…

Something clicked. “I know you, don’t I?”

His frown deepened, which I couldn’t really blame him for. It was a fairly odd question, and damn it, my mouth was going to get me thrown out again--

“In a manner of speaking, perhaps.” I sighed in relief. At least he wasn’t dismissing me out of hand, and it made me wonder what he dealt with on a regular basis if that wasn’t the oddest thing he’d heard.

“Sit, if you wouldn’t mind,” he said, indicating the armchair in front of his desk.

I complied, and he drew a bit closer. “I’ve had a lot of patients, so we may have run into each other long ago. But where do you think you know me from?” he asked in a careful tone.

I thought about the calm and measured voice, digging through my memories for the details.

“I….think my parents talked to you around the time I was born,” I said haltingly. I could remember that much, but the memories themselves were pretty fuzzy.

“I think it had to do with my condition,” I added, “but I think I explained that when I contacted your-”

His eyes narrowed in concentration. “Congenital analgesia, correct?”

I nodded, and his eyes widened slightly in understanding.

“That explains it. Yes, I do know you in a way, then. I was your parents’ primary medical consultant prior to your birth, though I’m surprised you were able to recall me.”

He pulled a decanter off the shelf, and poured himself a glass of water. “Would you like a drink?” I declined the offer politely, and he set it down.

“There was a discrepancy in your genetic data and your parents’ genetic records that led me to believe you might suffer from congenital analgesia, yes. A mutated gene that previous individuals with your condition possessed. But your parents and the other doctors disagreed with my analysis at the time, which I can’t blame them for. I was significantly less well-known at the time-” he smiled ruefully at this, “and my analysis was mostly speculation.”

He drank from his glass. “I kept tabs on you for a few years, but there were no suspicious incidences in your medical records, so I let it drop pretty quickly. I assumed I’d been wrong, and it’s not exactly the easiest thing to explain. I must say, it’s nice to know I wasn’t wrong, but in this case, I wish I had been.”

I nodded slowly. So many things were starting to make sense now. “In that case, I’m doubly glad to meet you, Doctor Jones. Thank you for…..at least trying to warn my parents about the possibility.”

The doctor half-grimaced. “Well, I have the “Do No Harm” oath to account for, you know. I uphold that as best as I can, but it can be frustrating if your advice is ignored entirely.”

He sighed. “But enough of that talk, I’m starting to feel egotistical. You came here because you believe I can help you with your condition, yes?”

I nodded.

“Before we start, I need to know exactly what you think my help will do for you. I don’t want to give you false hopes before we begin, and I need to make sure you understand exactly what you’re getting yourself into.”

“Well, that’s not exactly the most positive start,” I mused. “But it’s still a start.”

“I think you can help me figure out how to avert my condition. Make it so I can actually feel pain and not get myself unknowingly injured as often.” I said simply.

“That, I might be able to do,” he said, and my excitement must have showed, because he quickly hastened to clarify. “It’s not guaranteed, and there’s a fair chance it could leave you in worse shape. Do you still want to hear about the procedure?” he said seriously.

I didn’t even have to think about it. “Yes.”

He grinned, and some of his tenseness seemed to evaporate. “Then let’s get started.”

—————————————————————————————————————————

The good doctor explained how my condition was believed to be a result of certain mutated genes in my body. One from each parent(thanks for that), and combined, they had the effect of ensuring that the pain receptors in my body were never turned on. Still there, still intact, just…sleeping.

All we had to do was trigger them.

Unfortunately, that seemingly simple step was a lot more difficult than it sounded. Surface-level pain didn’t seem to work, and Doctor Jones was reluctant to try electroshock therapy on me without knowing what my limits were.

A week turned to two, then three, then a month.

It’s been three months since I went to Doctor Jones’s so far, and we haven’t gotten too far on the whole “feeling pain” thing.

It was frustrating, but honestly, that wasn’t the hardest part. That came from having to deal with my colleagues and the like, who just couldn’t understand why I would want to feel pain. It left me pissed whenever someone questioned it, and it strained my temper to the edge.

Something had to give, and that something was me. “Isn’t it a good thing?” a junior coworker asked, hanging in the doorway after I’d dismissed him. “To not feel pain?”

In response, I reached for the medical kit on my desk, and pulled out a long, thin needle that I sterilised with rubbing alcohol.

He winced when the needle slid easily through the upper skin on my forearm, and I watched him impassively.

“That’s what it’s like,” I said coldly. “Now imagine what it would be like if that needle happened to go through something more vital, like an artery or a vein or the important stuff in the back of your head. Imagine not being able to feel any of that, not even knowing what’s killed you or scarred you or ruined your life.”

“That’s what it’s like.” I motioned for him to get out, and he did so hurriedly. I sighed, rubbing my eyes tiredly.

He hadn’t deserved that. He’d started recently, he’d just been curious, but he’d been the unlucky last in a long line of people who I was sick of justifying myself to.

The needle was an afterthought by the time I remembered it was there, and I pulled it out swiftly, carefully.

Crimson blood welled from the small puncture, and I wished I could feel the sting for the umpteenth time as it trickled down my arm.

—————————————————————————————————————————

It was midway through the fourth month when we finally got something. Having exhausted all other options, and with my willing consent, Doctor Jones had elected to try and use selective electrical and hormone-based stimulation.

The whole thing went more quickly that I’d thought it would.My skin was still tingling lightly from the electricity, and Jones looked at me expectantly when it was done.

“Anything?” I pinched my forearm, feeling a resounding sense of disappointment when I only got the usual feeling of skin against skin.

I shook my head, and he slumped slightly. “Needle?” I asked, and he handed me one, having cleaned and sterilised it beforehand.

I slid the needle in expectantly, ready for the disappointment I’d get when it did nothing as usual. What I didn’t expect was the brief sting that I felt as the needle went in, and I pulled it out with a jolt.

Jones watched me curiously, a conclusion dawning in his eyes. “Did you….” He left the sentence unfinished, and I turned to him slowly. “That stung.”

Naturally, I left that session excited, and was back pretty quickly for another. Call it strange if you want, but pain was interesting to me. It was fresh and new, and it meant the end to a life of tiptoeing and constant watchfulness.

By the third session, we’d determined that the treatment hadn’t been fully effective - it wasn’t a complete sense of pain, just stings and a warm feeling against my skin.

It was still something, though. It was getting stronger and more pronounced.

When the knife slipped from my fingers in the kitchen at dinner, I almost relished in the sting of the cut it left along my hand.

At the fifth session, Doctor Jones stopped me on the way out. “Would you stay for a moment, please?”

I was a bit confused, but I sat all the same, and he settled himself next to me. “What is pain to you?” he asked, his tone low and serious.

It took me longer than I thought to give him an answer. “It’s….interesting,” I said, chewing my lip thoughtfully. “It’s something I’ve never felt before. It’s odd, definitely, but it’s good. It means I don’t have to live with an eye on my surroundings at any waking moment.”

Jones had been slowly relaxing as I spoke, but a frown crossed his face at my last two statements.

“I can understand the sentiment,” he said, “but you need to remember that ultimately, what we’re doing here is to help you feel pain, not seek it out. Pain is still pain. It’s good because it lets you know that something’s wrong, and you need to find a way to fix that, but it’s not something you go looking for.”

Looking back on that day, I really wish I’d taken his advice to heart. He deserved better than that from me. He’d earned that much, at least.

By the tenth session, Doctor Jones seemed satisfied with the progress we’d made. “You’re just like anyone else now,” he said, offering me a smile. “You don’t need to worry about your condition anymore.”

I thanked him. I shook hands with him. I left him. That was the last time I met Doctor Jones.

My life took a different turn after that. I finished a lot of things I’d had to stop doing, did more things I couldn’t even think of doing before. I remade myself, remade my world.

But I never really lost that sense of rebellion, that free spirit that I’d buried inside me. It just changed a bit, made me something of a thrill seeker. That’s probably why I eventually became a police officer.

Action with purpose and pay and duty. A lot of rules, but they were simple ones, and easy enough to work within when I needed to.

That’s probably what led me to the situation I’m in now.

It was a cold night in December when we got the call about a break in at the bank.

A night guard had spotted a suspicious group approaching, and he got a call through.

Enough to tell us that they were after the gold that had recently been deposited there, and that they were well-armed before the sound of gunfire cut him off.

Given that the gold would have been shipped out the next day to a more heavily secured location, the department had suspected something from the start, and they’d had people stationed nearby.

My team was the first on scene that night, and when we arrived, we were greeted by a hail of gunfire.

We avoided what we could, but hits were definitely coming in, and we had to bail from the car. My partner grunted as he dropped to the ground, and then-

Shots rang out, and I saw red splash across his leg and his side. He howled in pain, and I knew I had to help him. Or rather, I was driven to. Morality and all that, you know.

I dived out of cover, firing wildly. They ducked for a few seconds, and I threw my body across his to cover him from shots, then dragged him back behind my point.

He groaned, and I hushed him quietly. “You’re gonna be okay, partner,” I said firmly, moving from my cover to fire a few shots before coming back to him. “You’re gonna be okay.”

He nodded silently before his eyes closed, his chest slowly rising and falling. It took another ten minutes for our backup to arrive, and another five for us to subdue the gunmen after that.

Paramedics were on the scene in moments, and I guided my fallen partner to an ambulance, ushering him into their care.

He stirred faintly as they laid him on a stretcher, looking at me with bleary eyes. “Thank you,” he muttered quietly, and then the gratitude in his eyes turned to horror and he grabbed the medic’s arm.

“What’s wrong?” I asked, rushing over. “Look!” he said, pointing at me, and then the medics were all over me, fussing and prodding, trying to force me into a stretcher.

I didn’t feel anything wrong. I just felt tired, more so than usual, but I had just been in a gunfight. But I met my partner’s gaze, and followed his horrified eyes down to my chest-

I stopped. There were holes in my uniform. Small, round holes, and a scarlet stain slowly spreading over my chest.

I’d been hit.

“Can you not feel it?!” my partner asked frantically, his own injuries for the moment. I shook my head numbly as they carried me to an ambulance, a doctor already frantically calling ahead.

No, I couldn’t. I couldn’t feel it at all. No stinging, no burning, none of the throbbing that I’d come to associate with pain.

Only a slow, spreading warmth across my chest. Nothing else.

Nothing at all. And that was perhaps the thing that scared me most as darkness began to crawl over my vision, the world growing dimmer and dimmer until it faded away completely.

0 notes