#covid pulse oximeter

Text

goddamn it dude I took one hit too many and am fighting off a panic attack fuck I just want to be able to get high again fuuuck my stupid little brain

#as soon as im aware of my breathing im in manual breathing mode n struggle to like.. automatically breathe#i literally have a pulse oximeter to check my lung capacity bc im a stupid fucking hypochondriac#it does help my anxiety tho at least#AHHHHH#i just wanna get out of my head :(#i have so much anxiety around respiratory health since covid dude it's so rough#okay I'm done goodbyeee#rAMbles

1 note

·

View note

Text

OK listen

GET YOUR BOOSTER. Like today

If you have been thinking about it please take this as a sign to prioritize it NOW. Don't wait, don't think to yourself "Oh I'll just finish this one thing and then look into appointments and then maaaaybe"

Nope, if you can take the booster, get it now.

A lot of places have free walk-ins, no appointment necessary. Also it doesn't matter if you've been exposed recently, you can still get the booster.

#also if you arent set up with a good thermometer and pulse oximeter get them#they are good to have around anyway and you might have a hard time sourcing them when or if you get sick#me and people i know who avoided covid all this time are now sick and its worse than i thought#i sincerely regret not prioritizing my 4th booster#i was busy i thought id have more time

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

📞9811464331 / 8130300415

📩[email protected]

#mideltainternational#fingertips#fingertipulseoximeter#Oximeter#covid#PulseOximeter#healthylifestyle#thermometer#coronavirus#medicaldevices#oxygen#medicalequipment#staysafe#PULSE#nebulizer#sanitizer#bodytemperature#healthcareprofessionals#Oximeters#mask#safety#Youtube

1 note

·

View note

Text

and its nights like these (covid) that i ask myself... how much difficulty breathing and chest pressure and light headedness/dizziness is normal and how much is a concern,,, we just dont know :')

#texted mother at 8pm on the dot to ask if i could borrow pulse oximeter#she never responded yayyyyy#i guess she went to bed without checking her phone but like#hi i have covid. i am your child. are u not concerned? are u not checking ur phone before going to sleep? so confused#maybe shes tired or smth and not on top of things idk trying to be normal abt this but i am feeling... afraid lol#im not gasping for breath or anything i just... feel a little bit out of breath constantly since like noon ish#oh well ig! going to sleep and praying its fine fhdksl maybe it'll be gone by tomorrow if i can just fucking SLEEP please dear god im tired#pippen needs 2nd breakfast#covid tw

0 notes

Text

Immediate action is needed to tackle the impact of ethnic and other biases in the use of medical devices, an independent review says.

It found pulse oximeter devices could be less accurate for people with darker skin tones, making it harder to spot dangerous falls in oxygen levels.

And it warned devices using artificial intelligence (AI) could under-estimate skin cancer in people with darker skin.

The review said fairer devices needed to be designed urgently.

In total, it made 18 recommendations for improvement. The government says it fully accepts the report's conclusions.

The review was commissioned in 2022 amid mounting concern that ethnic minorities faced greater Covid risks.

It looked closely at three types of device where there is potential for "substantial" harm to patients:

• optical medical devices such as pulse oximeters, which send light waves through a patient's skin to estimate the level of oxygen in the blood. The light can behave differently depending on skin tone

• AI in healthcare

• polygenic risk scores, which combine the results of several genetic tests to help estimate an individual's risk of disease and are used mostly for research purposes

Pulse oximeters were used frequently during the Covid pandemic, for example, alongside other observations, to help judge whether a patient needed hospital admission and treatment.[...]

Chest X-rays

One example is the potential under-diagnosis of skin cancers for people with darker skin.

This would probably be a result of machines being 'trained' predominantly on images of lighter skin tones, the team explains.

Another concern arises when using AI systems for reading chest x-rays - which are mainly trained on images taken of men, who tend to have larger lung capacities.

This could potentially lead to underdiagnosis of heart disease in women, the report suggests, worsening an already long-standing problem.

Call me a fucking extremist but I don't think white people should be building AI and I definitely don't think it should be put in medical devices when the medical industry is already so full of its own systemic bias and especially before there's proper regulations about AI and without more expansive protections for BIPOC in the medical industry.

If you put racist medical device on the market and encourage people to use it knowing it can misdiagnose heart problems and cancer in people with dark skin then they should be able to take you to court for everything youve ever had ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

76 notes

·

View notes

Text

Started a new Ko Fi goal for a portable small air purifier to take to my medical appointments and make them safer / less risky for me to catch covid at (and keep me safer from my family potentially exposing me to it), any support sent my way will be going towards this for the time being.

I have to get some invasive dental work done soon and there’s a huge covid surge rn so this would help to have on hand, as I’m immune compromised and have cardiovascular issues that make catching it dangerous for me. (As evidenced by the pulse oximeter pic)

Currently already 65% of the way there! If I’m able to order it I’ll post pictures when it shows up and give my review of it (for transparency, so you guys have proof of what your help is going towards)

78 notes

·

View notes

Text

Buckle up folks because this is a long post -

Tips for newly diagnosed dysautonomia patients:

- Drink a lot of water (so much water guys. Especially if you have hypovolemic types of dysautonomia, like hypovolemic POTS, it’s crucial)

- Keep up with electrolytes/ salt intake. Vitassium makes salt pills, chews, and tablets. I personally prefer the tablets because I can just suck on them for a while, but I know a few people who prefer the pills.

- Compression socks help, A LOT! One major component of dysautonomia, in general, is blood pooling (which can greatly increase your risk of fainting). The compression/construction helps blood flow and return back to your heart and brain

- Your disability(s) are valid, even if you don’t pass out/pass out a lot!! Only about 1/3 of people with POTS (one of the most common types of dysautonomia) pass out! And of those, few pass out regularly/daily (such as myself). No matter what, you are valid! Even if you’re undiagnosed, even if your case is “mild”, even if you manage it well without much help; you’re valid!

- Especially for those of you who are just being introduced to disability (likely because of long COVID), it’s okay to grieve the life you used to have/planned to have. You can live a wonderful, full life with these conditions (and other conditions), it just may require more accommodations than you anticipated!

- DONT BE AFRAID TO ACCOMODATE YOURSELF! Seriously, use mobility aids, get a 504/IEP, and make your space(s) accessible to yourself! I use forearm crutches for short distances, but because of how severe my dysautonomia is, I’m reliant on a wheelchair (with someone pushing me/motorized aid) to go more than a couple hundred feet/longer (or anything that requires standing for more than 5-10 minutes).

- Get a pulse oximeter or watch! Certain types of dysautonomia may cause lowered oxygen (hypoxia) because of a lack of available blood. It’s extremely important to monitor this and make sure you’re aware of your oxygen levels!

- Find community! I personally love using “stuff that works”. It not only lets you crowdsource for information about medications or treatments, but lets you message other people with the same condition(s) as you.

- If you feel like something is wrong, please talk to your doctor. I know it’s scary, especially if you have medical trauma/PTSD on top of these conditions, but it can literally be lifesaving. I noticed a sudden uptick in chest pain and casually mentioned it to my doctor. Sure enough, we found I have two types of arrhythmias (p-wave inversion and flutters) Now I’m pushing for genetic testing to see if my diagnosed EDS is vEDS/cvEDS

- Don’t be afraid to start and try medications! I’ve tried numerous medications and haven’t found anything that works quite right yet, but that doesn’t mean I won’t :). And some of you may not need medication! You may be able to manage with lifestyle changes, or IV therapy, which is great! Do what works FOR YOU. Everyone is different!

- Rest days are productive! Your body is working really hard to keep you alive, it’s okay to take a break! Take care of yourself, really, it’s okay to conserve spoons.

#dysautonomia#disability#disabilties#disabled#potsawareness#pots syndrome#inappropriate sinus tachycardia#orthostatic intolerance#postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome#orthostatic hypotension#vasodilator#vasovagal syncope#neurocardiac#ehlers danlos type 3#hypermobilty syndrome#pure autonomic failure#PAF#Familial dysautonomia#panysdysautonomia#neurally mediated hypotension#multiple system atrophy#autoimmune#autoimmune autonomic gangliopathy#autonomic#dysfunctionality#accessibleness#accessibility#accessible posts#long covid#covid pandemic

334 notes

·

View notes

Text

current covid progress: im on day 3~4 or so. my fever is 101 degrees and i was actually relatively lucid for a while until i crashed down again. cough suppressant and plain mucinex has been helping a ton. i wish i had a pulse oximeter but i dont think we have one….. so far the most annoying symptoms have been the sore throat and cough

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

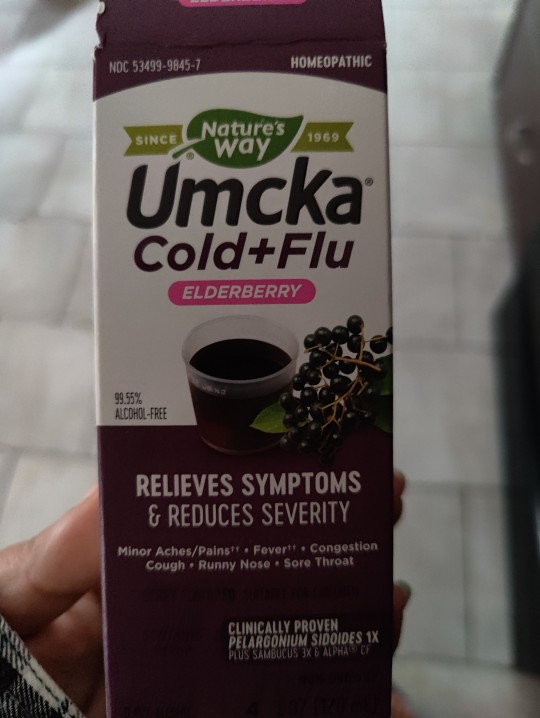

Unfriendly started a Whole Foods order via Prime today at 8 am ish since we're both just exhausted. We needed cough drops and some other things. He had picked up a bag of the Vicks kind and those are harsh. They kept triggering my cough. Probably great if you're just super sinus-y or just have a sore throat.

I added this syrup on a whim and it seems to be helping. The cold med cocktail has fucked up my gut and that is never fun but even less so when you're miserable with cold symptoms. I woke up just stuffy and exhausted. I used the Neti pot, which helped but only somewhat until this got in my system. And it tastes pretty good for a cold med.

This has been so aggravating. It started 2 weekends ago and was just sniffles and a sore throat. I was ok enough to do a hooping class that Sunday. That week was manageable. On that Wednesday, I almost canceled my dental check up for Thursday but when I found out that my hygienist's next opening was in May 2023, I let them know my symptoms and how they felt about seeing me. I wasn't coughing much at the time. The receptionist texted my hygienist to see if she was comfortable. I definitely did not want her to feel uncomfortable and let the receptionist know I tested Covid negative. That went well, though the drive was tiring. Ditto for the retinal doctor appointment the next day (Friday).

Then last Saturday it just went downhill. Coughing so much my chest hurt as well as my throat. Just so rundown. Since I relapsed and it was worse, I thought it might be Covid since one of the variants had relapsing as a symptom. But no. Until Thanksgiving it was just a big blur of feeling like shit and going through tissues. I told Unfriendly that whatever muscles are affected when you cough must be ripped by now.

On Thanksgiving I had to break out an old Albuterol inhaler because I needed it. Also had a low grade fever. Yesterday was the first day I got some restful sleep but only during the day. It's worse at night. That was also the day my chest felt better but then my eyes started leaking gunk. Woke up with my right eye basically crusted shut ☹️

This reminds me of the colds I'd get as a kid / teen but with those I couldn't keep water down. The only thing I could keep down was Sprite.

So, it's either that homeopathic cold syrup that's helping or my body is slowly getting it together. I'm just glad I don't have that "oh no is this bronchitis" feeling anymore. I kept checking the pulse oximeter and all was fine.

Anyway, if you made it this far, what was your fave turkey day food if you partook or what is a food item you are looking forward to during the holidays?

#I've had bronchitis that turned into pneumonia before#and the kind of bronchitis that is just a dry cough with no other symptoms#that was weird#my body is a lemon#new worry is thin retinas ugh#still need to share that story#heckin cold 2022

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

Micro Story: Caffeine

Story Content and Summary - 1,132 words. No resus. A gentle, first-person POV story about a reaction to coffee. Written gender neutral. Hurt/comfort. 🏳️🌈

--

“Are you all right?”

You raise your eyebrows at me, watching as I sit slumped at the breakfast table. I have a headache, the kind that feels like approaching summer storms.

“I’m getting a migraine.” My voice is embarrassing in its pitifulness.

“Oh, I’m sorry.” You hover, unsure if you should touch me. Sometimes the migraines make my skin hurt. “What can I do for you? Want a glass of water?”

“Water would be good…” I close my eyes and grind the lids with the heels of my hands. “Actually, can I have some of your coffee?”

In this household, we keep caffeinated coffee, which you mostly drink, and decaffeinated coffee, which is all for me.

I hear the silence of your hesitation before you ask: “Are you sure?”

“Yeah, it might help my head.” I drop my hands and give you a wobbly smile to reassure you. You nod and offer me your own tentative grin. Making coffee is something you can do to help. You like feeling useful, and I so often have problems you can’t solve.

Soon, I have a hot cup of drip in my hands, smoothed out with a splash of half-and-half. Caffeinated coffee is good; decaf beans aren’t always easy to find, and I miss the variety of roasts available to people who can tolerate caffeine.

“Want some toast or eggs with that?” you ask.

“Both.” I am confident I’ll be hungry when my head feels better, and I know coffee on an empty stomach isn’t the best idea.

You are kind and make us breakfast, and by the time it’s ready I feel like eating. I go on to get cleaned up for the day, feeling better and better as the minutes tick by. On the agenda: Work in the backyard until it rains or it’s time for lunch. Don’t get sunburned. My headache fades until it’s nothing but smoke on the horizon, and I pull on some yard clothes and follow you outside.

I make it an hour.

The problem starts with a fluttering sensation in my chest. I think at first I have indigestion, but then I stand up from my crouch by the flower bed. A cold sweat breaks out across my forehead, and I sway. You have your back to me, so you don’t see me wavering on my feet. What you notice instead is that I’ve suddenly gone silent, my chatter terminating mid-sentence.

“Are you all right?” The same question as before. I’m standing in the yard with my hand pressed to my stomach, hoping the lightheadedness and nausea will pass.

The fluttering in my chest worsens, and I identify the sensation as palpitations. I wonder if I can catch my pulse rate on my watch without alerting you, but it’s too late. You are already up and headed in my direction, evidently seeing something concerning in my sweaty face.

I shiver, even though it’s already in the eighties at this early hour, and you take my arm.

“Come sit down.” You pull me toward the patio furniture. I follow. My legs feel insubstantial.

The fluttering in my chest increases pace until it feels like hammering, and I’m breathing fast. I let you ease me into a chair, watch as you crouch in front of me, trying to judge my condition by the look on my face. Your hand reaches out, cups the clammy skin of my cheek.

“Do you feel faint? You look pale.”

I nod, breathless now. I just want to feel better.

“My heart,” I pant, hurriedly continuing when I see a look of alarm pass over your face. “My heart’s beating really fast. I shouldn’t have had that coffee.”

You nod, relaxing just a bit. You look more sympathetic than anything else, and you don’t chastise me. No “I told you so,” or “You always do this.” You are, above all else, kind.

Your fingers move from my face to my neck, pressing against my carotid. I watch your face grow distant as you concentrate, then frown. “Can you stand? I want to get you inside, out of the sun. I can get that pulse oximeter we bought for COVID.”

I start to rise, but you stop me with a hand on the center of my chest. “Hey! Go slow. You don’t have chest pains, do you?”

“No.” It’s the truth, but at this point I’m frightened and my lips tremble. You can tell I’m still unsteady on my feet as we rise together, so you keep hold of my arm and lead me inside. The world around me cants and wheels lazily. I wonder if I’m going to vomit.

The air indoors is crisp, and you set me down on the sofa. I try to fold over and put my head between my knees, but then I can’t breathe, so I have to push myself upright. I’m quickly losing control of myself, my own breathy gasps loud in my ears.

I hardly notice that you’ve gone anywhere when you’re back, carrying your phone and a glass of water and the promised pulse ox.

“Hey,” you say, clipping the little white clamp on my damp index finger. “Try to slow your breathing. You’re going to be okay.”

I close my eyes and lean against the back of the sofa. You have your hands on my legs, rubbing my thighs as you encourage me to calm down.

“Your heart rate is pretty high,” you say, “but if you can take some deep breaths, I don’t think I have to call an ambulance.”

“How high?”

“Don’t worry about the number. Just take a deep breath. In… out… in… out…”

My hands are shaking. Hell, my entire body is shaking. If this goes on much longer, I’m going to cry.

“Just keep breathing.” Your voice is soothing. “You’re okay. In… out…”

I try to match your pace, relaxing my body against the upholstery.

“It’s already helping,” you reassure me. “You’re doing such a good job.”

Another moment passes and you climb to your feet and sit down on the sofa. My eyes are still closed, but I feel your arm come around my shoulders. You adjust my hand so that you can still read the pulse oximeter, then reach up to trail your fingers down my sweaty cheek.

“In, and out…”

It’s getting easier to breathe, so I lean against you, relaxing into the soothing nature of your touch.

“You’ll be back to normal before you know it,” you murmur. Your hand moves to my hair, smoothing it back from my face.

My trembling quiets, and I draw an easy breath.

“Good.” Your voice remains low-pitched and gentle. “You can just sit here with me for a while and relax, okay? We have all the time in the world.”

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Great read. Many lesser known criminals behind the scenes. Basically this guy went to China and perpetuated their lies. Collaborated the fake videos as real and promoted the use of ventilators even though he knew they were killing people. Below is short extract from article.

This survival rate was greatly reduced, however, by the treatment protocol which Callahan and his colleagues used on patients, following “Chinese expert consensus” to employ “invasive mechanical ventilation” as the “first choice” for people with moderate to severe respiratory distress—in part to protect medical staff. As Callahan recalled:

When they got to a point when the drugs were no longer working, when the oxygen wasn’t helping, when the pulse oximeter readings dropped to 70, 60, 50… there was only one thing Callahan’s colleagues could do to keep them alive: anesthetize them and place them on ventilators… Except what Callahan was seeing was that patients were being put on ventilators faster than they were coming off them.

It’s not terribly surprising that patients were being put on ventilators faster than they were coming off—because as we now know, the ventilators were killing them.

Studies later revealed that patients over age 65 who were put on mechanical ventilators experienced a 97.2% mortality rate in the initial months of Covid—effectively a death sentence—before a grassroots campaign put a stop to the practice. To put this in perspective, patients over age 65 were more than 26 times as likely to survive if they were not placed on mechanical ventilators.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

instead of fighting with my insurance company to cover the damn pulse oximeter my doctor wanted me to have (it's durable medical equipment to monitor a health concern and i already have one condition on record that can result in low blood oxygen but fuck me and my doctor i guess) i bought a cheap one off amazon, and like. yeah no my heart rate is absolutely very high sometimes! i'm usually around 70 bpm at rest but when i feel weird it is up in the low 100s! why's it doing that! has it always done that and i didn't notice or is my autonomic system still fucked up? we don't know yet!

again: probably fine, doctor was not worried, but good to get a baseline now when i'm probably going to have heart problems in the future anyway, possibly sooner than later bc of COVID.

really i'm just annoyed it's so itchy. cass suggested taking an antihistamine above and beyond my daily allergy med and like. yeah i'm there i'm dying

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

#pulseoximeter#covid#oximeter#medical#health#medicalequipment#coronavirus#oxygen#oxygenconcentrator#pulse#oxygengenerator#ventilátor#medicaloxygen#oxygentank#testkit#thermometer#channels#nebulizer#healthcare#staysafe#safetyfirst#bipap#respiratoryphysiology#hospital#Youtube

0 notes

Text

I tested positive for covid this morning and I was going through an article about how to ease symptoms and I found this list of supplies

It took longer than I'd like to admit for me to realize that the rows aren't related. I initially thought it was a puzzle

Sat here trying to figure out why pet food was paired with pulse oximeter

Tried to solve the riddle of the covid supplies grid like this random health website was a Professor Layton game

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Columbia University's Mailman School of Public Health: Lets Talk About Racism | Columbia Public

Our researchers are shining a light on discrimination’s effect on the public’s health and taking steps to stop it.

In March of 2020, when then-Mayor Bill DeBlasio announced that the New York City Police Department would be responsible for enforcing mandates related to the raging COVID-19 pandemic, Seth J. Prins, MPH ’10, PhD ’16, had a bad feeling. “We saw anecdotal reports in the media that most of the people being arrested or given summonses were Black,” says Prins, assistant professor of Epidemiology and Sociomedical Sciences.

Sure enough, once data became available, Prins and his research team found that ZIP codes with a higher percentage of Black residents had significantly higher rates of COVID-19–specific court summonses and arrests, even after researchers took into account what percentage of people in each area were following social distancing rules. The team’s findings suggested that tasking police with enforcing mandates may have contributed to overpolicing of Black communities and the harms that result. Living in a neighborhood with a high rate of police stops has been associated with elevated rates of anxiety, post-traumatic stress, and even asthma. Prins and his colleagues found that pandemic policing mirrored the discretionary nature of the city’s stop-and-frisk program, which was deemed unconstitutional in 2013 due to racially discriminatory practices.

“It was a sick irony,” he says. “Not only did the policy increase close contact with police, who had incredibly low vaccination rates and often weren’t wearing masks, but also the people arrested were taken to crowded jails, where transmission rates were extremely high, and then sent back to their communities, which were already experiencing disproportionately high rates of coronavirus.”

His team’s report is one of several highlighting the ways in which the COVID-19 pandemic brought to the fore the long-standing effects of racism on public health, with findings of far higher death rates in this country among people of color. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention declared racism a serious public health threat in 2021, following decades of research supporting the idea that structural racism is a significant driver of the social determinants of health, impacting everything from where people live and where their children go to school to the quality of the air they breathe, the food they eat, and the healthcare they receive. In recent years, Columbia Mailman School researchers have published numerous studies that underscore the persistent and devastating effects of racism on public health and illustrate the ways in which historically marginalized groups experience deep-seated health inequities that lead to higher rates of diabetes, hypertension, obesity, asthma, and heart disease, as well as a shorter life expectancy.

In her course titled The Untold Stories in U.S. Health Policy History, Heather Butts, JD, MPH, assistant professor of Health Policy and Management, guides students through an examination of policies that have embedded structural racism in healthcare over several decades. Among them is redlining, a racially biased mortgage-appraisal policy dating to the 1930s that led to food deserts (and the adverse health impacts that result) and other environmental adversities. More recently, research has shown that pulse oximeters are less effective on people with darker pigmentation. Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, “You had Black and brown people going to their doctors and saying, ‘I’m having trouble breathing,’” she notes. “The doctor says, ‘The oximeter says your oxygen level is 96, you’re good to go.’ Meanwhile, that’s not an accurate reading.”

By continuing to probe the less obvious ways in which these historic mindsets continue to affect society, the researchers hope to contribute to a conversation whose ultimate goal is true health equity. Ami Zota, ScD, MS, who recently joined the School, has published research linking elevated levels of endocrine-disrupting chemicals in the bodies of Black, Asian, and Latinx women to products, such as skin lighteners, hair straighteners, and fragranced feminine care products, that reinforce Eurocentric beauty norms. Discrimination based on hair style and texture has been directly traced to a lack of access to economic opportunity.

She also noted a subtle racism in some of the responses she got from the media covering the work. Some reporters asked her why, if the OB-GYN community had discouraged douching, Black women were still engaging in the practice. “They took the approach of vilifying the user,” she says.

So pervasive is structural racism that it affects the temperature of the air circulating within our homes. Diana Hernández, PhD, associate professor of Sociomedical Sciences, has documented how racism has resulted in both segregation and a lack of investment in housing among certain populations, with enduring implications for physical and mental health. Hernández is a sociologist who conducts much of her research in the South Bronx, where she grew up in Section 8 housing. She has found that people living in poverty and people of color are more likely to live in energy-inefficient homes (such as those with poor insulation), despite consuming less energy overall. Energy insecurity—the inability to meet basic household energy needs—is associated with poor sleep, mental strain, and respiratory illness. Affected households might cope with the lack of heat by using ovens, stoves, or space heaters to warm their homes (exacerbating the risk of fire and contributing to respiratory problems), and by wearing coats and extra layers of clothing indoors. They might spend their days in bed, tucked under blankets and quilts, and forgo food, medicines, and other necessities. Hernández tells the story of one woman who sent her kids to school with holes in their shoes so that she could afford to keep the lights on at home.

Though the energy crisis of the 1970s and ’80s led to the implementation of some programs that address home-energy insecurity, only about 1 in 5 eligible Americans actually obtain benefits. In addition to a lack of awareness about where and how to access help, people with limited incomes face administrative burdens, from having to take time off work and pay for transit to submitting documents verifying identity and need. Energy insecurity also tends to be internalized in a way that other issues aren’t, says Hernández, and is often interpreted as a personal failure. “There are ways people navigate the food landscape—by visiting food pantries or accessing Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program benefits, for example—that are not available when it comes to energy,” she says, a situation that can affect social relations. In managing the shame and stigma associated with a lack of heat or power, many will keep friends and relatives at a distance.

Prins, whose early-career work in the policy realm spurred him to ask bigger-picture questions about racism and our country’s drug policy, has written extensively about the school-to-prison pipeline, a set of practices that make it more likely for some adolescents to be criminalized and ensnared in the legal system than to receive a quality education. The phenomenon gathered steam in the 1990s, part of a trend that saw the government cut spending in welfare, education, and housing while investing in systems of surveillance, punishment, and incarceration. “There are over 10 million students in the United States who go to a school that has a police officer but no nurse, counselor, social worker, or guidance counselor,” Prins says. Out-of-school suspensions have more than doubled over the past 40 years, and these policies have been borne disproportionately by adolescents of color, which is directly related to the preponderance of Black people in the nation’s criminal legal system.

Many Columbia Mailman School researchers have had the satisfaction of watching their work translate into real-world change. Zota testified before policymakers in California, Washington, and elsewhere as they considered regulations on beauty and personal care products, for instance, and saw the Toxic-Free Cosmetics Act, which bans the use of 24 hazardous ingredients from personal care products, passed in 2020. (Eighteen states, including California and New York, have also passed laws banning discrimination based on hair style and texture in the workplace and in schools.) A write-up in The Washington Post about Zota’s research into the presence of harmful chemicals in fast food led Sen. Dianne Feinstein of California to take the issue on and spurred Rep. Raja Krishnamoorthi of Illinois to petition the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) about it.

The wins can be gratifying, but Zota and the others acknowledge that, like racism, entrenched interests including Big Pharma, Big Food, and other industries can obstruct the work getting done. For example, thanks in part to the trailblazing research of the Columbia Center for Children’s Environmental Health, Congress instituted a federal ban on seven phthalates in levels exceeding 0.1 percent in toys and children’s products. But the dangerous chemicals can still be found in clothing, shower curtains, detergents, shampoos, and other products. Zota points to a lack of enforcement mechanisms for various consumer protection laws and to a dearth of funding for implementation. Last year, she published a paper looking at the effects of phthalates on learning and attention among children and recommending their elimination from food contact substances, only to see the FDA rule soon after that the petrochemical industry could continue using the most common phthalates—and leaving out any mention of health concerns in its decision. Facing challenges related to climate change, she noted, the industry appears to be digging in when it comes to the production of plastic.

Some progress is being made where the school-to-prison pipeline is concerned. Prins points to pilot programs in New York City that use restorative justice practices in schools to deal more holistically with disciplinary issues and that train teachers to be less discriminatory when applying discipline. But such measures can only go so far. Truly addressing the structural issues behind the school-to-prison pipeline, Prins says, will require a fundamental shift, one where social services are redirected from punishment to prevention. Similarly, he says, addressing mental health and substance use issues related to exploitation in the workplace shouldn’t be about offering underpaid and overworked people seminars on work-life balance. Policymakers should be looking at things like enforcing overtime laws and making it easier for people to unionize.

Systemic change will likely come about only once different questions start getting asked—and different people ask them. In 2019, Zota, whose parents hail from rural India, created Agents of Change in Environmental Justice, a fellowship aimed at amplifying the voices of environmental health scientists from marginalized backgrounds. The program’s move to Columbia with Zota’s arrival complements the work of RISE (Resilience, Inclusion, Solidarity, and Empowerment), a peer mentor program launched at the School in 2018. These days, Zota says, most of the people shaping public perspectives in the environmental health field are older, male, and white, but the members of her program—which works with the nonprofit Environmental Health News to amplify research and engage with the public—offer different lived experiences. “Whether you’re talking about climate justice or environmental justice, if you’ve grown up in one of the communities that is hardest hit, that is going to shape how you view the problem and how you view solutions.” Participants in Agents of Change write essays and produce podcasts and videos. Graduates, including at least four Columbia Mailman School alumni, already have been invited to give talks at the National Institutes of Health and the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

A new initiative capitalizing on the expertise of Epidemiology professor Mary Beth Terry, PhD ’99, will tackle systemic health problems among historically marginalized groups in a revolutionarily holistic way. In January, Terry was named director of the Center to Improve Chronic Disease Outcomes through Multi-level and Multi-generational Approaches Unifying Novel Interventions and Training for Health Equity (known as COMMUNITY). While the citywide center has roots in public health, it incorporates representatives from cardiology, oncology, neurology, nursing, and general medicine and draws expertise from across Columbia University. The goal is for the Columbia researchers, working with colleagues from Cornell, NewYork-Presbyterian, Hunter College, and the City University of New York, to engage with the communities Columbia Mailman School serves, particularly the Black and Latinx communities, across several diseases at once. Whereas most research programs get their funding through a connection to individual diseases, the aim here is to break down silos and focus on more comprehensive interventions.

Terry calls this new initiative the realization of a 20-year dream shared by the entire team, whose members have wanted to work together, given the common antecedents to many chronic diseases. “This new funding focuses on developing and validating interventions as we have so much descriptive epidemiology already,” she says. “These data have existed for decades. We need scalable, successful interventions.”

Terry notes that community health workers, who tend to have large networks and inspire trust, will be central to achieving health equity. They are already part of a program focused on improving outcomes for people juggling multiple chronic diseases, including a sleep program recently launched in the Latinx community in Washington Heights. A Harlem project will rely on community health workers engaging with churches to identify candidates for colorectal cancer screening, as the guidelines recently changed in response to a surge in diagnoses among young Black men. Terry expects the combined initiatives, which are led by her Columbia colleagues, to improve health and help build the evidence for the cost-effectiveness of community health workers, and ultimately to fund them better.

Hernández, too, sees leveraging community networks—in her case, within reimagined multiple-unit housing—as a way to bridge gaps in public health. Practitioners have long worked in gathering places such as churches, particularly in Black communities, to get public health messages across. “In some ways,” she says, “sharing an address can be more of a connection point than sharing faith. There are so many things that can be done to think about meeting people where they are, reducing barriers, and reaching populations that are quote-unquote hard to reach.”

Researchers affiliated with the COMMUNITY Center will continue the work that Columbia Mailman School has long undertaken with community organizations such as the Harlem-based WE ACT for Environmental Justice—work that centers the concerns of people of color. Like Zota’s fellowship, COMMUNITY involves an educational element, including training the next generation of new investigators who are interested in combating the health inequities of chronic diseases. This deliberate passing on of knowledge is critical. “To me, structural racism is not having the mentors you need to move up the ranks,” says Butts. As an African American with degrees from three Ivy League universities, Butts stands as a living example of the change she and her colleagues all believe is possible.

#Systemic Racism#american racism#Columbia University's Mailman School of Public Health: Lets Talk About Racism

5 notes

·

View notes