#cyprian sterry

Text

A "social and professional role": the story of Captain Samuel Packard

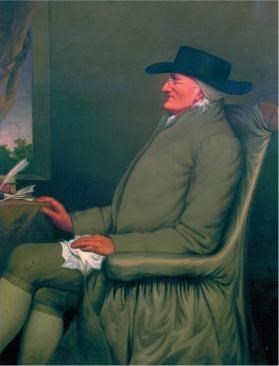

There are many subjects I could write about here. Either looking at vital records for Abington, Massachusetts to see where Packards pop up, results on Family Search for the surname of Packard, or mentions in a "Genealogical Dictionary" seemingly. [1] What I am inquiring here about is a man named Captain Samuel Packard painted by an American painter named James Earl, in the last years of his life, in circa 1794. The oil on canvas painting, which measures 35 by 29 1/4 inches, is of a prominent man in New England, begging the question: who is this man?

A photo of the above painting, held by the RISD Museum, is reposted here from the RISD website based on the Creative Commons license used for all RISD Museum works, which lets "others remix, tweak, and build upon your work non-commercially, as long as they credit you and license their new creations under the identical terms." This post is a non-commercial work as it is intended purely for educational purposes about the Packard family.

In their description of the above painting, [2] the RISD Museum writes that

Seated casually in a Windsor chair, Samuel Packard signals his social and professional role in the new republic. The plush drapery, the decorative column, Packard’s fashionable bright-hued waistcoat all suggest that is a man of wealth. The ship in the distance and the spyglass refer to his interests in maritime trade. A merchant and talented mariner, Packard owned 39 vessels that sailed from Providence. Around the time of this portrait, Packard had completed missions abroad for George Washington, so the ships may also allude to Packard’s diplomatic travels.

He was married to a woman named Abigail Congdon and had a daughter with her which had the same name (Abigail). They were married on December 13, 1789 in Saint Pauls Church, Narragansett, Washington, Rhode Island as the record shows:

Page 345 of Vital record of Rhode Island, 1636-1850, Vol 10, within the section "St. Paul's Church marriages"

In January 1942, the Rhode Island Historical Society displayed the painting of Samuel Packard on the cover of their historical magazine. One article titled "A Rhode Islander Goes West to Indiana" by George A. White, Jr. explained more about Capt. Samuel Packard's role in the early United States. He wrote on pages 21-22 that

Captain Samuel Packard was the son of Nathaniel Packard and was born in Providence, October 17, 1760. His father owned land bordering North Main, Howard, and Try Streets. Captain Samuel Packard's life followed a similar pattern...he was a mariner, ship master, ship--owner, and merchant. He owned 39 ships, sailing from Providence to all ports of the world...an ardent admirer of George Washington...Captain Packard acted for him in secret work [during the revolutionary war]...[after 1797] Captain Packard and his family lived in a mansion [in Providence] built of wood and brick, measuring 25 feet on the street and 60 feet deep. It was three stories high...On December 13, 1789, Captain Packard had married Abigail Congdon...in 1798, Abigail (Congdon) Packard inherited a portion of the Congdon homestead farm on Boston Neck...in the early 1800's Captain Packard purchased the remainder of the farm...Captain Packard owned land in Cranston, R.I., and in Illinois. Captain Packard furnished his Providence and North Kingston homes with fine furniture, china, and silver

Mr. White continues by quoting letters from Captain Packard's son, John Congdon Packard, describing his experiences "out West" which are addressed to Captain Packard's residence in North Kingston, Rhode Island.

Note: This was originally posted on Mar. 9, 2018 on the main Packed with Packards WordPress blog (it can also be found on the Wayback Machine here). My research is still ongoing, so some conclusions in this piece may change in the future.

Apart from the confusion of Samuel Packard who arrived in 1638 with Captain Samuel Packard (as noted here and here), some got it right. It is evident that Captain Packard was a "revolutionary patriot," which was also recognized by William Shaw Bowen who gave some of the Captain's belongings to the Redwood Library in 1878. He may have commanded a company during the war with the British from 1812-1815 as well, although this be a confusion with another Packard.

There is no doubt that Captain Packard was renowned as a master of ships, while transporting important financial papers. While it would seem, reportedly, was pointed to the spot where Roger Williams, Rhode Island's founder, was buried, with one book saying that, this is actually referencing Nathaniel Packard who married a woman named Nabby. He was, however, one of the original members of the Providence Marine Corps of Artillery and, later on, the Providence Marine Society.

Captain Packard clearly had a role in the revolutionary war in moving supplies past the British blockade as Vol 4 of Naval Documents in the American Revolution reports:

These events happened in April 1776

I still question whether this is the right Packard, however.

Captain Packard went beyond the owning of slaves by Zachariah Packard as noted in my family history. He sailed a ship to the coast of Africa looking for Black Africans to enslave in 1797 contrary to Rhode Island law. As the University Publications of America noted in a guide to certain Rhode Island Historical Society records,

Moreover, Moses Brown’s letters reveal not only the Abolition Society’s formal legal stratagems but also its traditional policy of intense but informal negotiating with slave traders who often yielded to the group’s demands without a court fight. Cyprian Sterry, for example, the principal slave trader in Providence during the 1790s with fifteen voyages to the African coast in 1794 alone, fully succumbed to the society’s persistent pressure. He escaped prosecution (along with his captain, Samuel Packard) for an African voyage involving the ship Ann by signing a written pledge to leave the slave trade forever.

Captain Packard was seemingly related to a Capt. Nathaniel Packard who was also in Rhode Island. Other books sadly only exist as snippets and hence do not give much information about his life. However, there is no doubt that he lived in Providence, Rhode Island near houses that nowadays are called historic (see pages 16 and 17 of this PDF).

Page 17 excerpt

You would be able to look at the deed books either by going to the Rhode Island State Archives, as noted here, or being at a Family Search Library.

He was alive and well in Providence in September 1794 when a ship, Hope, came into the harbor:

Courtesy of Chronicling America.

Thanks to Family Search, I have also discovered:

Captain Packard (called Samuel Packard in record) living in Providence, Providence, RI in 1790 and in 1800, as summarized also in an article later on on this blog, using the original records.

Captain Packard (called Samuel Packard in record) living in Providence RI's West District in 1810.

Captain Packard and Abigail's daughter died in 1860 (no publicly available image is available)

Abigail, Captain Packard's wife, died in 1854 (no publicly available image is available)

As it was noted, in one of the books I found, that a Captain Packard died at age 80 in 1809. There is a Samuel Packard who died in 1824 at sea with a tombstone in Rhode Island along with a Samuel Packard Jr who died in Providence in 1799. His tombstone makes it clear that he was born in Oct 1760 and died on July 17, 1760. This is clear from the following transcription:

In the memory of

Capt

Samuel Packard

Who Died

July 17, 1820

Aged

59 Years & 9 Months

Via page 382 of Vital record of Rhode Island, 1636-1850, Vol 10, shows deaths of varying Packards in Rhode Island.

Notes

[1] Also it is worth noting that no Packard popped up here, meaning that there is nothing in Family Search's Massachusetts, Town Clerk...Town Records, 1626-2001 specifically for Norfolk, Weymouth or Land records 1642-1644. Packards could be on this page, but is also questionable. Additionally, I could look at online records of Hingham to see if the Packards appear, possible Packards on pages such as this one or this. But I have already done that in the past and future searches at this time are a waste.

[2] The Rhode Island Medical Journal writes that "several other portraits by James Earl in the RISD show bear a strong stylistic similarity [to the one of Dr. Amos Thoop], particularly that of Capt. Samuel Packard of Providence, a successful ship captain, merchant, and ship owner of Throop’s era." The painting is in the Smithsonian's Art Inventories Catalog but resides at RISD. As one person writes about the collections in Rhode Island, "Postwar Windsor production at Providence for domestic use is indicated in the accounts of the Proud brothers and in a circa-1795 portrait of Capt. Samuel Packard seated in a sack-back Windsor."

© 2018-2022 Burkely Hermann. All rights reserved.

#samuel packard#slavery#slavers#slave traders#slave trade#black history#black people#black lives matter#black history matters#enslaved people#genealogy#family history#packards#genealogy research#rhode island#risd museum#Cyprian Sterry#moses brown#chronicling america

1 note

·

View note

Text

"A man of wealth": Samuel Packard, the Rhode Island slaver [part 1]

In March 2018, I first wrote about Samuel Packard, my great-great-great-great-great grand uncle, and his role in the transatlantic slave trade as a slaver, otherwise known as a slave trader. [1] Thanks to a new database, Enslaved: Peoples of the Historical Slave Trade, I found that Samuel's role as a slaver was much more extensive than I had originally believed. His acts helped reinforce what Isabel Wilkerson describes as a racial caste system that uses rigid, arbitrary boundaries to keep groupings of people apart. [2] Such a system reinforces a social order supported by culture and passes through the generations, with the signal of one's rank in the hierarchical system as determined by race, with terms like "black" and "white" applied to people's appearance. However, Wilkerson argues that caste is rigid and fixed, while race is superficial and subject to change to meet the needs of the dominant caste within the United States. Ultimately, inherited physical characteristics are used to differentiate "inner abilities and group value" and maintain and manage the caste system within the United States. In the case of Samuel, he was part of this system, reinforcing it with his actions time and time again, like some of my other ancestors. [3] However, as I noted in the past, that he was not a slaveowner. This article aims to pull away the false narrative used to cover up the history of enslavement and how offensive the institution of slavery was itself, noting the part Samuel played in this history, recognizing who he is as a person, following the advice of Beth Wylie, a White female genealogist. This article also aims to not make White people comfortable with the past or sugarcoat anything, but challenge existing notions, as suggested by Black genealogist Adrienne Fikes in early June.

Of the 402 ships which sailed from Rhode Island to Africa from 1784 and 1807, 55 of them came from Providence, accounting for 14 percent of the state's slave trade. [4] One of those ships was a sloop named General Greene, registered in Providence. On November 16, 1793, it began sailing from Rhode Island. The ship was owned by Samuel Packard, Cyprian Sterry, Philip Allen, and Zachary Allen. [5] Helmed by a captain named "Ross," the General Greene arrived in Gorée, Senegambia sometime in 1793, with 101 souls loaded onto the ship by force. By the time the ship had reached the Dutch colony of Suriname, sometime in April 1794, only 84 enslaved Black people, who had been trafficked across the Atlantic Ocean, were remaining. This meant that 17%, or 17 people, died during the Middle Passage. In Suriname, enslaved Black people were needed, as were Indigenous people, to make the colony viable, even though enslaved Black people were treated terribly, and many escaped their plantations. [6] The Zachary Allen noted here was undoubtedly the father of the textile manufacturer born in 1795, who was born in 1739. He has been described as a "successful merchant" who amassed a great quantity of capital. It is not known who the "Philip Allen" was and whether the said person was related to the manufacturer born in 1785.

On July 12, 1794, the General Greene returned to its home port somewhere in Rhode Island. The owners had been paid, the ship was not captured, and the enslaved Black people disembarked. In this trip and for all slave ships, the captain was completely in charge, with the duty to "navigate an efficient course, maintain authority over the crew, fill the vessel to capacity with enslaved peoples, and negotiate a high sale price for the enslaved cargo at port markets." [7] Sadly, we do not know the names of the 101 people who were aboard the General Greene in bondage at the beginning of the journey, nor those at the end, we only know the number of those aboard the vessel.

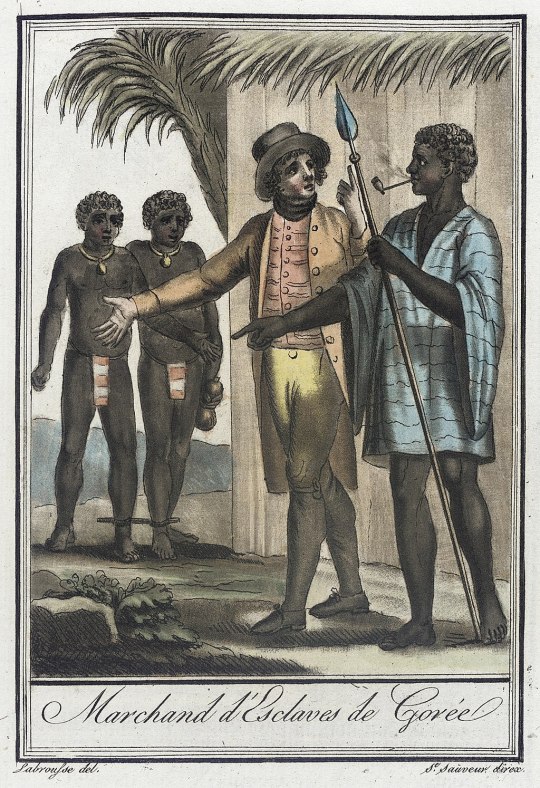

A slave trader of Gorée, engraving of c. 1797, by Jacques Grasset de Saint-Sauveur, via Wikimedia, but in public domain

Gorée is infamous for being the House of Slaves, which was built between 1780 and 1784 by an Afro-French family, the Métis. It has been described as having "one of the slave warehouses through which Africans passed on their way to the Americas," symbolic no matter how many Africans passed through, especially when it comes to its "door of no return." In the case of Senegambia (present-day Senegal, The Gambia, and Guinea-Bissau, portions of Mauritania, Mali, and Guinea), in 1794, it was partitioned between the French and British. This journey may also be the one the Philadelphia Inquirer referred to in September 1794 when it talked about a Captain Samuel Packard traveling from Barbados, which was then part of the British West Indies. [8] As for Cyprian, he was one of the biggest slave traders in Providence, he "financed at least 18 voyages that transported more than 1,500 enslaved persons to the southern United States and the Caribbean during the 1790s."

Later that year, on November 28, 1794, the GeneralGreene departed once more from Rhode Island, this time with John Stanton as the captain. [9] It would go on a 196 day voyage. The ship reached Iles de Los sometime in 1795, with 99 souls forced aboard. When it reached Savannah, Georgia in May of that year, only 88 remained, meaning 11% had died when trafficked across the Atlantic. The General Greene returned back to Rhode Island sometime after June of the same year. Iles de Los is a set of Islands off Conakry, Guinea. At the time, there was a trading post employing workers who repaired ships, and pilots for rivers, on the island. It would be controlled by the British beginning in 1818 and ending in 1904, later to be part of French Guinea from 1904 to 1958. Those on the islands were the Baga people and spoke the Baga language, specifically a Kaloum or Kalum dialect. That same year as the General Greene left the state, the African Union Society of African descendants in Rhode Island was organized in Providence to serve the needs of Black people in the state itself. [10] In Georgia, slavers from Rhode Island, especially in the early 1790s, dominated the slave trade to the state. Samuel and Cyprian were integral to this trade, with the latter described as the "wealthiest ship owner and most active slave trader" in the state. Again, the names of those on the ship were not listed, so we only know the number of those on the ship.

Sometime in 1795, James Earl, a Massachusetts-born artist, released his unsigned 35 x 29 oil painting, on canvas, of Samuel, then 45 years old. RISD described this painting as signaling his "social and professional role in the new republic," as he sits in a Windsor Chair, noting his waistcoat indicates he is "a man of wealth," with the background referring to his "interests in maritime trade." The museum also calls him a "merchant and talented mariner," who owned 39 vessels that sailed from Providence itself. Of course, his role in the slave trade is never mentioned. This is not a surprise, as the 1942 profile of Samuel in the Rhode Island History notes the same. [11] Furthermore, the absence of the slave trade from Earl's painting is not unique. As Edna Gabler points out, Black people in paintings by Charles Wilson Peale, John Trumbull, and others, "occupy subordinate positions, are rarely identified by name, and are most often used as props, background accessories, or foils," or, in this case, not mentioned at all.

The following year, on October 24, 1795, the Ann, a ship registered in Providence, and owned by Samuel and Cyprian, departed from Rhode Island. [12] Unlike the other journeys, Samuel was the captain. The ship would land somewhere on the African continent, with 133 people forced aboard. 70% of these African captives were men, about 26% were boys, and around 4% were women. Almost 26% of those aboard were children. 13 of these souls, 10% to be exact, would die during the Middle Passage. When the ship arrived at Spanish-controlled city of Havana, in Cuba, sometime in August 1796, only 120 remained, and all those in bondage disembarked there, with Samuel and the ship returning to Rhode Island. At the time, Havana was one of "the largest slave markets in the world," with over 600,000 Africans taken from West Africa and shipped to Cuba over three centuries. The Ann would later be sold in Havana, seemingly in September 1796. [13] Like with the other ships noted in this article, those in bondage aboard the Ann are not named, a clear form of dehumanization.

An enslaved Afro-Cuban in the 19th century, via Wikimedia Commons

At the time, landowners were beginning to win concessions that would change how land would be owned in Cuba, a process that would continue until 1820. [14] Values of land were rising and Cuban planters were consolidating their power on the island, importing machines from other European colonies, like those in the British West Indies, to strengthen the sugar industry. When Samuel landed in Cuba, he would have seen the beginning of changes in Cuban society, with population numbers beginning to rise, as did profits and agricultural production, with new position for the class of Cuban Creoles. The number of enslaved Black people on the island increased as demand for more workers continued to grow, especially after the import of White workers wasn't successful. An average of 1,143 enslaved Black folks in chains were brought into Cuba each year, between 1763 and 1789. The plantations in the British West Indies, including Barbados, the Leeward Islands, Jamaica, Ceded Islands, Trinidad, and British Guiana, were very profitable, with the average rate of profit being 6.1% between 1792 and 1798, based on the plantations studied. [15] Even so, the end of a sugar boom in the 1790s led politicians and planters to demand that the slave trade be ended once and for all.

On January 9, 1796, the James, a schooner registered in Providence, owned by Samuel and Cyprien, with Albert Fuller as the captain, departed from Rhode Island. [16] It went on a 216-day voyage. Once in Africa, 119 souls were forced aboard the ship in bondage. By the time it arrived in Savannah, Georgia, in mid-August 1796, only 98 enslaved Black people were remaining. As a result, 17.5%, or 21 people, had died along the way. The ship returned to Rhode Island by late October 1796. The ship later had Nathan Sterry as its captain when registered in January 1797, with Samuel as its owner. Sterry would also be the captain of a ship, the Mary, upon which three enslaved Black people attempted a mutiny to escape their conditions by taking control of the ship, even though this was, unfortunately, not successful. In this last illegal slave trading expedition which Samuel was involved in, those in chains, aboard the James, were again only listed as a number, but no names were provided.

Painting of Moses Brown via NPS

On March 11, 1797, the Providence Abolition Society petitioned then-Attorney General Charles Lee, charging that the Ann, a ship of Cyprian and Samuel, had sailed under Samuel's command to travel to the African coast for enslaved people, even though this violated Rhode Island law. [17] A law had been passed in 1774 which made it illegal for citizens of the state to bring enslaved people into the state unless they had a bond to "bring them out again within one year" and those people brought to the state in defiance of the law would be "set free." However, the law caused slavers to sell captives in other ports while bringing their capital back to Rhode Island with them. The later was followed in later years, in 1787, by a measure which "banned participation by Rhode Islanders in the African slave trade." [18]

Some argued that the state's involvement in the slave trade was "part of a scramble by merchants to find something to trade and to market"with those involved earning a sizable profit. Following the enactment of the law in Rhode Island, similar laws passed in Connecticut and Massachusetts after being pressured by Quaker merchant merchant Moses Brown and Samuel Hopkins, a minister. The critical factor, according to I. Eliot Wentworth of University of Massachusetts Amherst's Special Collections & University Archives, of these laws was enforcing them, and when that did not happen, it lead to the creation of the Providence Society for Abolishing the Slave Trade. [19] It was mostly comprised of Quakers and had a membership of about 180 members. The society would face resistance from those invested in the trade, but still "played a valued role in supporting individuals of African descent in defending their rights in court." It won a judgement against Caleb Gardner, a merchant, in 1791, for "carrying out a slaving voyage in his brigantine Hope."

Cyprian, who owned half of the ships involved in the illegal slave trade, left it behind in order to avoid a crippling fine, signing a pledge to leave the slave trade forever, as did Samuel, from what I have read. [20] These efforts, like those of the Providence Abolition Society, were important since legislation against slave-trading in Rhode Island was hard to enforce, as noted earlier. For instance, a merchant and influential slaveowner named John Brown, a person who was instrumental in founding Brown University, tried in 1796 for violating the Slave Trade Act of 1794, prohibiting ships in American ports from bringing in enslaved people from any foreign country. At first he was convicted and his ship, the Hope, was confiscated for violation of federal law. However, as the case went through the legal system, he was ultimately acquitted, in a jury trial, "emerging with an acquittal and a judgment for costs against the Providence Abolition Society." [21] He even cited the arrangement the society made with Cyprian as part of a plea to stop prosecution against him.

As it turned out, the judge who presided over the case (Benjamin Bourn) and the federal prosecutor (Ray Greene) were allies of Brown, and the trial itself had a "devastating effect on the Providence Abolition Society, which went into a rapid decline." This was because, while by 1793, the Providence Society's activity had shifted to pushing for federal legislation, it remained dormant from February 1793 to November 1821. The Society was revived by David Howell and its name changed to the Providence Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery, continuing to meet until 1827. John later beat another prosecution in 1798, and in 1799, Samuel Bosworth, Surveyor of the Port of Bristol, was kidnapped by eight men dressed by Indigenous people, intimidating officials and putting a "halt to local enforcement of the Slave Trade Act" within Rhode Island.

Via RISD, also painted by James Earl, and in the public domain

Samuel went onto become a wealthy shipowner and merchant who lived in a three-story-high lavish mansion in Providence with his wife Abigail Congdon. [22] He had married Abigail on December 13, 1789 at Saint Paul's Church in Rhode Island, with a Reverend William Smith as the minister. In 1798, Abigail inherited a portion of the Congdon homestead farm on Boston Neck. Samuel and Abigail had a number a children in later years, clearly living in Providence in 1800, just as he had in 1790. Their children included Abigail in 1802, Samuel in 1804, and Susan in 1806. By 1804, Samuel would work for the Providence Insurance Company, which ensured products like sugar, lived at Westminster Street in Providence (a property he bought in 1797). [23]

The Providence Insurance Company was founded on the initiative "of the Browns," including John, the arrogant slaver, in 1799. Other prominent shopping merchants, like Thomas Poynton Ives, John Innes Clarke, and Moses Lippitt, were on its board of directors. Samuel would be a member of the Providence Marine Society (PMS) and part of the Providence Marine Corps of Artillery after March 1803. [26] The latter group, founded in 1801 by PMS members, was a "private mutual aid society for sea captains," and while it later became part of the Rhode Island militia, the group itself "never served in active combat." The PMS, on the other hand, was a "mutual aid society for sea captains" founded in 1798.

Samuel also, reportedly, remembered George Washington fondly. This was not a surprise. In 1788, Olney Winsor, son of Samuel Windsor, a pastor of the Baptist Church of Providence, traveled to Alexandria on a sloop of which Samuel was the captain: the Susan. Both landed in Alexandria, went to a plantation at Col. Mason's Neck, seeing the control of slavemasters over those they enslaved firsthand, and met with George Washington himself.

By 1798, Cyprian was still living in Providence, owning a house, with a tenant: Brown & Ives, said to be a leader "in American commerce and industry for many years," and part of the Brown family which financed Brown University. [24] The company had been formed in a partnership between Nicholas Brown and Thomas Poynton Ives in 1791. The same year, Samuel is reported as having to have a summer house, house and barn, and perhaps another barn elsewhere in the city.

This wealth would not be possible without his involvement in the illegal slave trade which trafficked human beings from Africa back to the Americas in bondage. Let us be clear. Samuel, like Cyprian, might be called a human trafficker in today's language, if what he did happened today, although the comparison of present-day human trafficking and the transatlantic slave trade is not exact due to the differences between these oppressive systems of exploitation. [25] When they were alive, however, Samuel and Cyprian would likely be called slavers or slave traders. We don't know if Abigail had any role or say in Samuel's involvement in the trade, as we have no written records from her that I am aware of at this time. Even so, she still benefited from it, as she lived a life of luxury with Samuel until his death in 1820.

Samuel would also reportedly own land in Cranston, Rhode Island and in Illinois, along with a home in North Kingston, while building a house on the land his wife inherited on the death of her father, John Congdon. [27] Items from his houses are currently in RISD. John's grandfather, Benjamin, was reputed to be a huge slaveowner, while John, who had ten children with his wife, Abigail Rose. He received a tract of land of unknown acreage in Boston Neck, on his father's death, and then in October 1, 1803, Thomas R. Congdon sold one hundred and fifty acres of the farm to Samuel Packard, later known as the "Packard Farm," later reaching 500 acres. John's father, according to a 1765 listing, had seven enslaved people, one man (Coff), two young boys (Roshad and Tom), one woman (Tent), and three others (Cato, Fortune, and Jimie), working for him, which he manumitted at the time. [28]

In 1811, Samuel was aboard a ship when it French privateers raided the vessel, and how he tried to take back the ship, but was captured. [29] He would be at sea for eight days, then in a French prison for another eight days. They remained in France for another three months until they were allowed to go home. 17 years earlier, on February 4, 1794, France had abolished slavery, declaring that "all men irrespective of color living in the colonies are French citizens" but it was not reinforced, and Napoleon re-instituted it on July 16, 1802. He still remained in Providence, as he had in years prior, specifically in the city's West District. [30]

Screenshot of the cemetery where Samuel and Abigail are buried with a close-up of the cemetery taken from Google Earth

He died in July 1820, [31] while Abigail died in May 1854. Before her death, she established the Providence Female Charitable Society, which aided "indigent women and children." Both Samuel and Abigail are buried at Historic New England’s Casey Farm. While no wills or probates are available from them, both were of a higher class than others in Rhode Island and more broadly in New England. For Samuel, land ownership remained an important marker of civic identity and a measure of independence, as it was for other Americans, as historian Nancy Isenberg points out. This was based on the idea that people were not free unless they had "the economic wherewithal" to control their destiny, which comes from land ownership, deriving from an old English idea that the "quality of the soil determines the quality of the people."

Coming back to Samuel, his wealth derived, in part, as noted earlier, from trafficking enslaved Black people who were taken from their homelands by force. What he did was illegal, since the passage of a Rhode Island law in 1787 prohibiting it, and the Slave Trade Act of 1794, the latter with possible seizure of ships and a $2,000 fine, a law amended many times over the years until the Act Prohibiting Importation of Slaves passed in 1807. Even so, he still engaged in the trade despite the illegality, meaning, if he had been charged for his crimes, and convicted, he would have paid a total of $2,400, in, let's say, 1797. [32] This would likely have been a drop in the bucket for him. If assessed today, he would be paying $47,900.00, in terms of real price/real wealth, one of the most accurate measures, tied to CPI, according to Measuring Worth. In any case, what Samuel did went against "justice, integrity, and uprightness among people," in the words of the Quakers, who petitioned the Rhode Island legislature to abolish the slave trade in June 1787, participating in what they called an "unrighteous and inhuman trade to Africa for Slaves," complete with "cruel bondage."

Hopefully this article is a step in reworking and reframing narratives, as Adrienne Fikes pointed in June of this year. It is part of, what she talks about, in understanding who you are, who are in relation to others, who you come from, who your ancestors are, while looking at harm of past and its impact today. She also points out the value of sharing what you find with descendants of future generations, as does Donya Williams and Brian Sheffey of Genealogy Adventures (those who interviewed Fikes), noting the importance of think of microaggressions and pain involved in Black genealogy. Fikes also argues, rightly, that understanding structural racism, and noting the evolution of slavery, not seeing it in past tense. Furthermore, she says recognizing the humanity of people is important as is the current reality of dignity and humanity stolen from Black people, as is generational wealth. With this all being said, I look forward to hearing from you all as I continue to research my enslaved ancestors, as part of actively doing something to dismantle a system which privileges White people, uncovering more stories of my ancestors, even if it is difficult and disturbing at times to confront. [33]

Note: This was originally posted on Aug. 25, 2021 on the main Packed with Packards WordPress blog (it can also be found on the Wayback Machine here). My research is still ongoing, so some conclusions in this piece may change in the future.

© 2021-2022 Burkely Hermann. All rights reserved.

#slavery#packards#genealogy#family history#genealogy research#lineage#ancestry#slave trade#black history matters#black lives matter#rhode island#gambia#suriname#slave ships#18th century#19th century#public domain#senegambia#savannah#goree#havana#cuba#middle passage#cyprian sterry#black women#plantations#moses brown#abolitionists#james earl#george washington

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nathaniel Packard's role in the odious slave trade

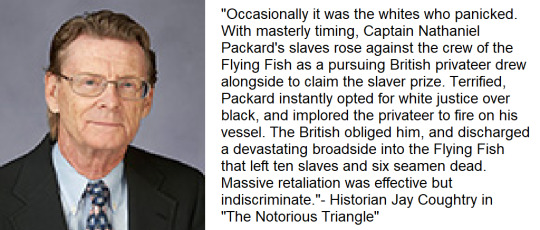

Page 158 of Coughtry's well-known 1981 book, Rhode Island and the African Slave Trade, 1700-1807 . He currently teaches at University of Nevada in Las Vegas.

Happy Black History Month! Slave trading runs in the Packard family as I've noted on this blog before. This article was a tough one to write because there are TWO Nathaniel Packards! While I tried to ask about this on /r/AskHistorians and received no reply, [1] I am operating with the educated assumption that the slave trading shown in the 1790s was from Nathaniel Packard, Jr., not his father, of the same name, Nathaniel Sr., as he will be called herein to distinguish from his son, who was the father of Samuel. I would further like to point out that Nathaniel Jr.'s mother was part of the Sterry family, and her first cousin, Cyprian, is the same one who Samuel worked with as a slave trader! [2] Not really a coincidence if you think about it.

Some may ask, how can you be so sure that this is the right Nathaniel? What if Nathaniel Sr. was the one involved in the trade of human beings? For one, I found out that Nathaniel Sr. was born in 1730, died in 1809 while his wife "Nabby" Abigail, was born in circa 1734, and she came to live with this Nathaniel in 1752, at age 18. [3] Her death in 1819, has not been confirmed. Nathaniel Sr. had a child with Abigail in 1769 (at age 39) named Elizabeth, in 1775 (at age 45) a child named Polly, and his child Nehemiah got married in 1777. [4] Furthermore, he probably wasn't engaged in slave trading in the 1790s, due to his age. After all, in 1790, Nathaniel Sr. would have been 61, and in 1799, he would have been 70. That seems a little old to be a captain of a ship, with anecdotal evidence suggesting that captains retired between 53 and 62. [5] I wish my evidence was stronger, but I decided to go with this article anyhow.

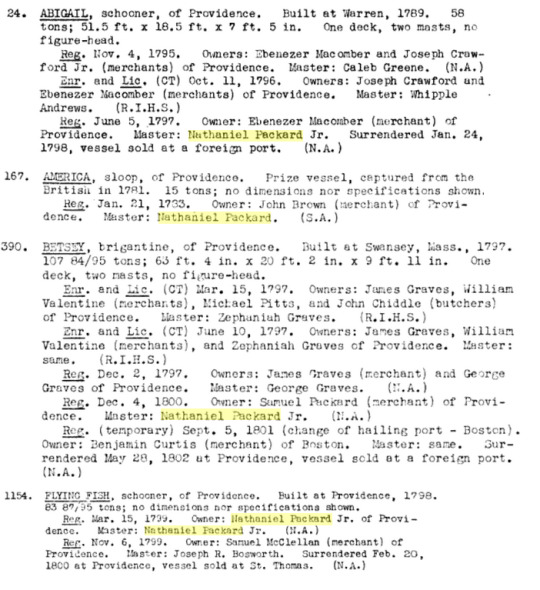

We do know that Nathaniel, my 2nd cousin eight times removed according to FamilySearch's "View my relationship" algorithm, was a captain, participating in the Revolutionary War, and reportedly having a similar career to his son, Samuel, owning land on North Main, Howard, and Try Streets in Providence. He was a master privateer during the revolution, captain of a sloop, called the America in 1776, and had a ship he was a captain of, the Sally, captured by the Royal Navy the same year. [6] That, and the story of the America, a ship appearing in thousands of results of the Naval Documents of the American Revolution Digital Edition, is for another day, whether I choose to write about it not. The age of Nathaniel, Jr., my third cousin seven times removed, is disputed. When he died in January 27, 1807, death notices recorded his age as 25, 35, or even 55. [7] At the time of his death, he owned a house on Providence's Main Street, with two houses and other buildings, and in 1801 he is noted as a sea captain, and as marrying a woman named Miss Margaret D. Paddleford in 1800. While he would have been born in 1782 if he was 25 years old in 1807, that means he would have been 15 years old in 1797, it is more likely he was 35 or 55, meaning that he would have been born in 1772 or 1752, although I am leaning more toward his birth in 1772, around the time his other siblings were born, than 1752.

Otherwise, what is known about his personal life is sketchy at best, even having a Find A Grave entry without a photograph of his gravestone. As such, writing about his story and its interconnection with the transatlantic slave trade is important, possibly even revealing more about him as a person. Whether he was a "man of wealth" like his brother, Samuel, or not, the fact remains that uncovering his connection to the slave trade is an important part of recognizing my collective past, the history of enslaved Black people, and much more. This article tries to counter what historians Erica Caple James and Malick W. Ghachem describe as "a still powerful tendency to marginalize or suppress the stories of black lives," with narratives about the past propagated as more marketable than alternatives that try to cut against the grain of “great man” history. [8]

Often Americans see themselves as exceptional people tied together by noble ideals, but this falls apart when history is taught fully and honestly "without omitting facts or telling outright lies" as Margaret Kimberley writes in Prejudential about the racial prejudice manifested by every single US president in history. For Nathaniel, the story starts in 1797. That year, he was the captain of four ships which crossed the Atlantic. The first was the Danish Harriet, which traveled to an unspecified region of Africa, from February to December, bringing with it 53 souls, most of which were men, and selling people in Havana, Cuba. Second was the Providence schooner, Abigail, owned by Ebenezer Macomber. Unlike the Harriet, which Nathaniel owned, this ship began its journey in Rhode Island. Similarly, it traveled to an unspecified region of Africa and sold 53 enslaved peoples, mostly men, in Havana. 11 souls perished during the voyage. [9]

The same year, and into 1798, he was captain, again, of the Harriet, now owned by J de Wint. It traveled once more to Havana, this time with 57 enslaved Black people on board. [10] A pattern emerges when combining data from slave voyages: from 1797 to 1800, Nathaniel, as captain or owner, transported 314 Africans in chains to Havana, Cuba, 85 who died during the Middle Passage, and 6+6 who may have died during the voyage or have a fate unknown, while 10-15 died in a slave revolt as described later in this article. Although after 1794 U.S. slave trade to Cuba was illegal, slave traders still made slave voyages to Havana, and "profited from their own Cuban plantations". This was amidst a societal change in Cuba, which changed from underdeveloped and unpopulated small settlements, ranches, and farms in 1763 to large tobacco and sugar plantations by 1838. This was accelerated by the import of hundreds of thousands of enslaved people during that time period, estimated at 400,000 by Hubert Aimes, benefiting Cuban planters, and a decree in 1789 which allowed foreigners and Spainards to sell as many enslaved people as they wanted in Cuba's ports. Land values rose as landowners, especially those involved in sugar production, gained more power and influence as the "sugar revolution" swept the island, with a 22.8% increase in enslaved people on the island from 1774 to 1827, and the planters depended on Spanish power more than ever to protect their investments. [11]

From pages 8, 60, 136, 360 of Ship Registers and Enrollments of Providence, Rhode Island, 1773-1939, Vol. 1, 1939, I believe the America was owned by his father.

The following year, he was captain, and owner, of the Flying Fish, a schooner from Providence. He co-owned the ship with Sam McClellan. This ship went to an unspecified part of Africa and sold 76 enslaved people in Havana, but they resisted with a "slave insurrection" noted. However, a voyage earlier that year with the same ship was more deadly, as almost half of enslaved people aboard died during the Middle Passage! [12] The ship had a tonnage of 85 tons, higher than some other ships.

It was then that Nathaniel would experience a revolt on the Flying Fish, which was transporting enslaved people. Ten of those on board would revolt, noted in the Newport Mercury. 10-15 enslaved people and 4-5 crewmen were killed in a failed revolt on this private armed vessel. While some sources said this was in 1800, the revolt was in late 1799, in actuality. [13] Coughtry, who I quoted at the beginning of this article, wrote:

Occasionally it was the whites who panicked. With masterly timing, Captain Nathaniel Packard's slaves rose against the crew of the Flying Fish as a pursuing British privateer drew alongside to claim the slaver prize. Terrified, Packard instantly opted for white justice over black, and implored the privateer to fire on his vessel. The British obliged him, and discharged a devastating broadside into the Flying Fish that left ten slaves and six seamen dead. Massive retaliation was effective but indiscriminate. On the few vessels that did experience slave revolts, captors and captives alike paid a high price for the latter's courage.

Nathaniel would be captain of the Betsey in 1800, Eliza in 1803, Minerva in 1794, Juno in 1805, and Dolphin in 1792. By 1800, he was married to Margaret Downs Paddleford, the daughter of well-off physician named Philip Paddleford and Margaret Downe. By the time they married, her mother had been dead or twenty years and Philip had married another woman, Elizabeth Macomber. The same year, friends of a 10-year-old Black male child, Peter Sharp, would testify against Nathaniel to the Providence Council. [14] In later years, in 1801 to 1802, he would be captain of the aforementioned slave ship, the Betsey. Only 94 of the enslaved people made it to the Americas and were sold in Havana, with 24 people perishing during the voyage across the Atlantic. [15] He did this while professing his religious ferment in his last will and testament, bequeathing money and personal property to his children and Margaret:

Will of Nathaniel in 1806, probated in 1807, noting his children and wife. [16]

Nathaniel was creating generational wealth, something which came in part from the trading of enslaved Black people. As Mary Elliott, curator on American slavery for The Smithsonian's National Museum of African American History and Culture noted in July 2019, some 12.5 million men, women and children of African descent were forced into the transatlantic slave trade, with the "sale of their bodies and the product of their labor [bringing]...the Atlantic world into being...[with] freedom was limited to maintain the enterprise of slavery and ensure power." She further said that Africans were forcibly migrated through the Middle Passage while the slave trade provided political power, wealth, and social standing for individuals, colonies, nation-states, and the church, while noting that enslaved black people "came from regions and ethnic groups throughout Africa." Although the U.S. international slave trade was made illegal in 1808, domestic slave trade increased, even as illegal slave trading continued internationally, with people such as my ancestor, Captain Samuel Packard, involved in it. What she next is significant to keep in mind:

Slavery affected everyone, from textile workers, bankers and ship builders in the North; to the elite planter class, working-class slave catchers and slave dealers in the South; to the yeoman farmers and poor white people who could not compete against free labor.

Furthermore, slavery itself was built and sustained by "black labor and black wombs", maintaining the economic system itself, with prosperity depending upon the "continuous flow of enslaved bodies", while a campaign of violence was waged against black people that "would rob them of an incalculable amount of wealth" following the end of Reconstruction in the 1870s. [17] Nathaniel, as well as his family, was part of this exploitation and it something that should be recognized, not hidden away or covered up as some people like to do with this history.

Notes

[1] On August 21, I asked "What age did sea captains, in the 18th century, retire?", adding in part "my common sense tells me he wouldn't be sailing a ship at that age and some scattered sources about this, when I did a quick search, did point to that." Unfortunately, a moderator removed the question for asking "basic facts," to which I wasn't happy (obviously), and was directed to another askhistorians thread. I posted a similar version of the question there, asking "Does anyone know what age did sea captains, in the 18th century (more specifically 1790s-early 1800s), retire?" And, just as I expected, I received NO reply. The lesson I took away from this is that you can't trust these forums to respond to you, and sometimes you just have to do the research yourself, with no help from anyone else, sad to say.

[2] Using this family relationship chart and explanatory post, I determined that Cyprian is the son of her uncle. This is because the brother of Abigail's father, Robert (1711-1789), was a man named Cyprian (1707-1772), who had a son named Cyprian (1752-1824), the one, and same, as the slave trader. So, that's the connection. Abigail and Nathaniel later had a daughter named Abigail, who married in 1784, and was named after her. In another interesting antecote, it appears that John Congdon, the father-in-law of 3rd cousin 7x removed, and the father of Abigail, the wife of Captain Samuel Packard, may have been a slave trader as well, as a Congdon is listed as captain of an unnamed slave trading vessel in 1762 and the Speedwell schooner from 1764 to 1765.

[3] Knowles, James D. Memoir of Roger Williams, the founder of the state of Rhode-Island (Boston: Lincoln, Edmands & Co., 1834), 432-433. Reprinted in "Notes on the Grave of Roger Williams," Apr. 20, 1907, Book Notes, Vol. 24, No. 8, p. 59. Relevant quote, reprinted from a letter in The American in 1819: "I am induced to lay before the public the following facts, communicated to me by the late Capt. Nathaniel Packard, of this town, about the year 1808...Captain Packard was son of Fearnot Packard, who lived in a small house, standing a little south of the house of Philip Allen, Esq. and about fifty feet south of the noted spring. In this house Captain Packard was born, in 1730, and died in 1809, being seventy-nine years old...Mrs. Nabby [Abigail] Packard, widow of Captain Packard, who is eighty-five years old, told me, this day, that her late husband had often mentioned the above facts to her; and his daughter, Miss Mary Packard, states, that her father often told her the same... Mrs. Nabby Packard, Nathaniel Packard's widow, told me this day, that she came to live where she now lives, when she was eighteen years old, which was sixty-seven years ago."

[4] "Rhode Island Town Births Index, 1639-1932", database, FamilySearch, 4 November 2020, Nathaniel Packard in entry for Elizabeth Sterry, 1857; "Rhode Island, Town Clerk, Vital and Town Records, 1630-1945," database with images, FamilySearch, 4 November 2020), Nathaniel Packard in entry for Elisabeth Sterry, 22 Nov 1857; citing Death, Providence, Providence, Rhode Island, United States, various city archives, Rhode Island; FHL microfilm 2,022,703; "Rhode Island, Town Clerk, Vital and Town Records, 1630-1945," database with images, FamilySearch, 4 November 2020, Nathanul Packard in entry for Polly Packard, 17 Dec 1858; citing Death, Providence, Providence, Rhode Island, United States, various city archives, Rhode Island; FHL microfilm 2,022,703; "Rhode Island Town Births Index, 1639-1932", database, FamilySearch, 4 November 2020), Nathaniel Packard in entry for Polly Packard, 1858; "Rhode Island Marriages, 1724-1916", database, FamilySearch, 22 January 2020), Nathaniel Packard in entry for Nehemiah Rhoads Packard, 1777.

[5] I'm referring to a 1931 New York Times story titled "37 YEARS AT SEA, CAPTAIN TO RETIRE; SHIP MASTER TO RETIRE" (noted a captain retiring at age 55), a U.S. Navy webpage saying you retire after age 62,and the life of Captain Edward Penniman (1831-1913) described by the National Park Service.

[6] White Jr., George Wylie. “A Rhode Islander Goes West to Indiana (1817-1818),” Rhode Island History, Vol I, No. 1, January 1942, p. 22; Lewisohn, Florence, The American Revolution's Second Front: Persons & Places Involved in the Danish West Indies & Some Other West Indian Islands (University of Texas, 1976), p. 12; "Captain Nathaniel Packard's Account Against the Rhode Island Sloop America, September 30, 1776," American Theatre from September 1, 1776, to October 31, 1776, Vol. 6, via Naval Documents of the American Revolution Digital Edition; "Owners of the Rhode Island Sloop America to Captain Nathaniel Packard, August 21, 1776," American Theatre from September 1, 1776, to October 31, 1776, Vol. 6, via Naval Documents of the American Revolution Digital Edition; "Lists of Prizes Condemned in the Vice Admiralty Court of Antigua, January 14, 1778," American Theatre from January 1, 1778 to March 31, 1778, Vol. 11, via Naval Documents of the American Revolution Digital Edition; "Governor Nicholas Cooke and John Jenckes to Captain Nathaniel Packard, February 3, 1776," American Theatre from January 1, 1776, to February 18, 1776, Vol. 3, via Naval Documents of the American Revolution Digital Edition; "Prizes Taken by British Ships in the Windward Islands, May 1, 1776," American Theatre from April 18, 1776, to May 8, 1776, Vol. 4, via Naval Documents of the American Revolution Digital Edition; "Journal of H.M. Sloop Pomona, Captain William Young, March 11, 1776," American Theatre from April 18, 1776, to May 8, 1776, Vol. 4, via Naval Documents of the American Revolution Digital Edition; "Potential Suspects," Gaspee Virtual Archives, accessed September 26, 2021. He was also said, according to the 1774 RI Colonial Census, to be living in Providence with his family, that year, and have tracts of Land in Providence as early as 1762. As a note on his FamilySearch profile proposes, he may have been involved in the Gaspee Affair in 1772.

[7] According to a note on his FamilySearch profile, a death notice was published in Providence Phoenix (Providence, R.I.), 31 Jan 1807, p. 3, col. 2, has an unclear date of either he was age 25, 35, or 55, with a reprint in the Columbian Centinel (Boston, Mass.), 4 Feb 1807, p. 2, giving his age as 25, the Salem Register (Salem, Mass.), 5 Feb 1807, p. 3, col. 3, giving his age as 35, the Independent Chronicle (Boston, Mass.), 5 Feb 1807, p. 3, giving his age as 25, and Newburyport Herald (Newburyport, Mass.), 6 Feb 1807, p. 3, col. 2, giving his age as 25. See the note for further sources of information beyond this sentence, mainly abstracting from probate records. He was also living in Providence in 1800, according to "United States Census, 1800," database with images, FamilySearch, accessed 26 September 2021, Nathanies Packard Jr, Providence, Providence, Rhode Island, United States; citing p. 211, NARA microfilm publication M32, (Washington D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.), roll 45; FHL microfilm 218,680, and his marriage is noted here: "Massachusetts Marriages, 1695-1910, 1921-1924", database, FamilySearch, 28 July 2021, Nathaniel Packard, 1800.

[8] Erica Caple James and Malick W. Ghachem, "Black Histories Matter," Perspectives of History, Sept. 1, 2015, accessed September 26, 2021.

[9] Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade - Database, "Voyage 35224, Harriet (1797)", with entry also in Peoples of the Historical Slave Trade database and another entry here; Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade - Database, "Voyage 36677, Abigail (1797)", with entry also in Peoples of the Historical Slave Trade database.

[10] Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade - Database, "Voyage 35225, Harriet (1798)", with entry also in Peoples of the Historical Slave Trade database.

[11] Franklin Knight, "The Transformation of Cuban Agriculture, 1763-1838" in Caribbean Slave Society and Economy: A Student Reader (ed. Hilary Beckles and Verene Shepherd, New York: The New Press, 1991), 69, 72, 74-78.

[12] Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade - Database, "Voyage 36727, Flying Fish (1799)", with entry also in Peoples of the Historical Slave Trade database; "Voyage 36726, Flying Fish (1799)", with entry also in Peoples of the Historical Slave Trade database and here.

[13] Eric Robert Taylor, If We Must Die: Shipboard Insurrections in the Era of the Atlantic Slave Trade, Vol. 38, 2009, p. 209; Naval Documents Related to the Quasi-war Between the United States and France: From Dec. 1800 to Dec. 1801, United States. Office of Naval Records and Library, 1935, p 397.

[14] U.S., Newspaper Extractions from the Northeast, 1704-1930 for Margaret D Paddleford, Massachusetts, Columbian Centinel, Marriage, Nabor-Ryonson, :Newspapers and Periodicals. American Antiquarian Society, Worcester, Massachusetts; Massachusetts, U.S., Compiled Birth, Marriage, and Death Records, 1700-1850 for Margaret Downs Padelford, Taunton; Massachusetts, U.S., Town Marriage Records, 1620-1850, Vital Records of Taunton, Margaret Downs of T. and Nathaniel Packard of Providence, Feb. 12, 1800, in T. Intention not recorded; Massachusetts, U.S., Wills and Probate Records, 1635-1991 for Philip Padelford, Bristol, Probate Records, Padeford, James - Paine, Sarah, pages 144 and 145; via page 11 of Descendants of Jonathan Padelford, 1628-1858 chart, where it almost looks like Margaret Brown; Children Bound to Labor: The Pauper Apprentice System in Early America, 2011, p. 43.

[15] Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade - Database, "Voyage 36753, Betsey (1802)", with entry also in Peoples of the Historical Slave Trade database.

[16] Will of Nathaniel Packard, 1807, Rhode Island, U.S., Wills and Probate Records, 1582-1932 for Nathaniel Packard, Providence, Wills and Index, Vol 10-11 1805-1815, Rhode Island, District and Probate Courts.

[17] Of note is what one writer, Nancy Isenberg, argued: that Americans believe in social mobility, but have a "long list of slurs and of terms" for people, and noted that "the discussion of class throughout our history has forced on the centrality of land and land ownership, as well as what I call breeds, or breeding", concepts which come from the British, and notes that another English idea is that "the wealth and the strength of the nation are based on the size of its population" and goes onto say that the English were focused on bloodlines, lineage, and pedigree, even more on inheritance, while saying that class has a specific geography with class-zoned neighborhoods, and stated that convincing people that poor whites are enemies of black Americans is a way to divide people, concluding that "not only are we not a post-racial society, we are certainly not a post-class society."

Note: This was originally posted on Feb. 6, 2023 on the main Packed with Packards WordPress blog (it can also be found on the Wayback Machine here). My research is still ongoing, so some conclusions in this piece may change in the future.

© 2023 Burkely Hermann. All rights reserved.

#packards#slave trade#slavery#enslaved people#black history matters#black lives matter#rhode island#providence#18th century#19th century#havana#cuba#spain#slave revolt#slave rebellion#middle passage#slaveowners#reconstruction#nancy isenberg

0 notes

Text

Captain Samuel Packard's illegal slave-trading and the cost of a $2,000 fine

ca. 1794, painting by James Earle, at the RISD Museum. "Seated casually in a Windsor chair, Samuel Packard signals his social and professional role in the new republic. The plush drapery, the decorative column, Packard’s fashionable bright-hued waistcoat all suggest that is a man of wealth. The ship in the distance and the spyglass refer to his interests in maritime trade. A merchant and talented mariner, Packard owned 39 vessels that sailed from Providence. Around the time of this portrait, Packard had completed missions abroad for George Washington, so the ships may also allude to Packard’s diplomatic travels." His role as a slave trader is NOT mentioned in this description, although I'm not sure why.

Building on my post in late September, I'd like to focus on how much my third cousin seven times removed, Captain Samuel Packard, who I first wrote about back in July 2021 would have paid had he been convicted of the anti-slave trade law of 1797, which has a fine of 100 Rhode Island pounds per violation, equivalent of one pound per dollar, and the Slave Trade Act of 1794 which carried with it a fee of $2,000. He was not convicted, even though the Providence Abolition Society had petitioned the Attorney General of Rhode Island, Charles Lee, in March 1797, charging that a ship, owned by Cyprian Sterry and Samuel, named the Ann, traveled to the African coast for enslaved people in violation of Rhode Island Law. Pressure from those invested in the slave trade prevented most convictions. While Samuel supposedly signed a pledge saying he would leave the slave trade forever, as I noted in my aforementioned post in July 2021, he retained his wealth and privilege.

In that post, I said that Samuel would have paid a total fine of $2,400 if he had been tried and convicted of his crimes in 1797. I stated that he would be paying $47,900.00, "in terms of real price/real wealth, one of the most accurate measures, tied to CPI, according to Measuring Worth". I'm not sure that is the most accurate measurement. Clearly the fine is not a commodity (consumer goods and services) nor a project (an investment or government expenditure). However, it is closest to income (flow of earnings). As such, the best would be real wage/real wealth, which measures the purchasing power of an income or wealth by its relative ability to by goods and services, as noted by Measuring Worth. That value is $61,100.00 in 2021 values. Still, this would have been probably a small price to pay for Samuel.

If Samuel had continued his slave trading activities, his ships could have been seized by U.S. authorities per a law in 1800. More fundamentally, he was unique in the sense that plantation owners were the main ones who substantially profited from enslaved peoples. The slave trade was relatively profitable, with at least 6% return, although there were maritime and commercial risks. According to Guillame Daudin's analysis of profitability of long-distance trading and slave trading for eighteenth century France, some investors bought small shares in many ships, spreading out their risks, and between voyages, shares in slips could be bought and sold freely. Others calculated that even if slave trading companies didn't profit from a specific voyage, it still led to "extra activities such as shipbuilding or the production of trade goods". Even The Economist stated that slavery was profitable for slaveowners but not for few others. Colonial Williamsburg explained a little more on their website:

A slave voyage was always a risky financial venture for the owners and investors...Also, the nature of trade along the African coast was ever changing, as the desirability and value of particular textile designs and colors, for example, varied month by month and from region to region...The ship captains drafted both experienced and inexperienced sailors, which created risks for the ship owners and investors. Slave ships were, then, dangerous, violent, and disease-ridden. Despite the risks, slave voyages proved to be greatly profitable for their investors. The ship captain faced a paradox, because it was in the crew’s interest to ensure that as many African captives survived as possible in order to be sold to the highest bidder in the Americas. The slavers’ and their investors’ aim was to sell the men, women, and children for the best prices, not to kill or disable them, but the crew often resorted to violence to control and demoralize the captives...Sighting land in the Americas was a relief for the captain and crew but must have brought new uncertainty and fear to those who had survived the Middle Passage. After the captain landed the ship in a port, African survivors were inventoried, fed, scrubbed, and oiled to create a healthier appearance...At every point of this horrific journey, the business of the slave trade and the enslaved individual’s role as commodity was present. Exchange, trade, and profits were the engines of the transatlantic slave trade"

Simply put, Samuel profited off the trade of human beings. As I noted in my previous post, he is equivalent to what we would call a human trafficker today, but was called a slaver or slave trader during the time he was alive.

Note: This was originally posted on Nov. 14, 2022 on the main Packed with Packards WordPress blog (it can also be found on the Wayback Machine here). My research is still ongoing, so some conclusions in this piece may change in the future.

© 2022 Burkely Hermann. All rights reserved.

#packards#slave trade#slavery#black history matters#black lives matter#genealogy#genealogy research#ancestry#lineage#18th century#1790s#wealth#privilege#slaveowners#middle passage#slave ships#human trafficking#slaver#rhode island

0 notes