#digitaldysmorphia

Text

Week 8: Beauty Filters: Unveiling the Impact on Beauty Standards and Self-Perception

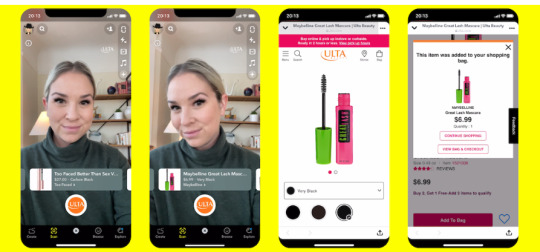

The evolution of AR masks and filters has been remarkable, with over 600 million people utilizing filters on Facebook or Instagram, as reported by Meta (Well, 2023). Snapchat pioneered face filters in 2015, introducing augmented reality into daily routines and enabling users to enhance their appearance, alter facial features, or virtually accessorize (Barker, 2020, p. 208) (as Figure 1). Even cosmetic companies have tapped into Snapchat's platform to promote their products, with Ulta Beauty introducing shoppable Snapchat AR lenses. This practice of 'digital adornment' has opened up new avenues for self-expression and interaction in the digital realm (Barker, 2020, p. 208)

Figure 1. Kendall Jenner uses Snapchat's beauty filter.

Figure 2. Ulta Beauty's Snapchat AR lenses.

However, beauty apps have contributed to the creation of unattainable beauty standards in our image-saturated culture (Coy-Dibley, 2016, p. 3). The 'pretty' filter, in particular, presents an idealized image devoid of flaws and perpetuates the beauty standard pushed by the beauty industry (Barker, 2020, p. 208). These filters can unexpectedly alter facial features, conforming to stereotypical feminine ideals by enlarging eyes and shrinking other proportions, with people of color experiencing unnatural skin-lightening effects (Barker, 2020, p. 213). Certain filters, like animal-themed ones, can unexpectedly alter facial features like enlarging eyes and shrinking other proportions (Barker, 2020, p. 213). Such filters evoke complex emotions about one's natural appearance and can lead to conflicts and discontent among users. For example, Allegra Clark's tweet shared her upset with the Snapchat filter. Some scholars even point out that unrealistic desires, such as flawless skin and large eyes, stem from a narrow Western beauty standard that excludes diversity (Hunt, 2019), highlighting the inequalities (Barker, 2020, p. 209).

Figure 3. Filter changes facial features in accordance with beauty standards.

Figure 4. Allegra Clark's tweet.

The use of beauty filters has also given rise to a phenomenon known as "selfie dysmorphia," where individuals seek treatments to alter their features to resemble their filtered appearances (Coy-Dibley, 2016, p. 2). This extends to "Snapchat dysmorphia," associated with body dysmorphic disorder, as users desire procedures to emulate their digital images (Hunt, 2019). Such as in the interview video below, Dr. Tijion Esho, in a video interview, highlights a case where a patient sought eye surgery to match the size depicted in a filter, only to find it impossible to achieve. This phenomenon contributes to social body dysmorphia, driven by influential beauty industries and cultural norms (Coy-Dibley, 2016, p. 2). Women face competition in media and digital representations, leading to social body dysmorphia, as beauty industries objectify and sexualize female bodies, perpetuating narrow femininity and societal pressure to conform to beauty standards (Coy-Dibley, 2016, p. 5).

youtube

In conclusion, while beauty filters offer new avenues for self-expression and interaction, they also perpetuate unattainable beauty standards, contribute to social body dysmorphia, and lead to the emergence of selfie dysmorphia. Recognizing these effects is crucial in fostering healthier digital environments and promoting diverse and inclusive beauty standards.

References

Barker, J. (2020). Making-up on mobile: The pretty filters and ugly implications of Snapchat. Fashion, Style & Popular Culture, 7(2), 207–221. https://doi.org/10.1386/fspc_00015_1

Coy-Dibley, I. (2016). “Digitized Dysmorphia” of the female body: the re/disfigurement of the image. Palgrave Communications, 2(1). https://doi.org/10.1057/palcomms.2016.40

Hunt, E. (2019, January 23). Faking it: How Selfie Dysmorphia Is Driving People to Seek Surgery. The Guardian; The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2019/jan/23/faking-it-how-selfie-dysmorphia-is-driving-people-to-seek-surgery

The Young Turks. (2016). Do Snapchat Beauty Filters Make You Look Better, Or Whiter? Www.youtube.com. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Qx_vQs2ioeo

Well, T. (2023). The Hidden Danger of Online Beauty Filters | Psychology Today Canada. Www.psychologytoday.com. https://www.psychologytoday.com/ca/blog/the-clarity/202303/can-beauty-filters-damage-your-self-esteem#:~:text=In%20addition%2C%20Meta%20reports%20that

#mda20009#beauty filters#beauty standards#digitaldysmorphia#snapchat#cosmetic surgery#diversity#stereotypes

0 notes

Text

Select an effect: should we fear face filters?

You’ve probably heard of AI or artificial intelligence, but what about AR?

Did you know you it’s available to use in most social media apps through filters?

This week’s lecture explains that ‘filters use augmented reality (AR) technology, which “allows the user to see the real world, with virtual objects superimposed upon or composited with the real world.”’ In other words, filters take the image of the real world and change it in some way, usually adding elements.

The lecture explains these filters are popular too, ‘with 700 million users across Meta products accessing AR in some capacity (usually filters) every month’.

Examples of filters:

- Beautification

- Humorous/funny face filters

- Animal

- Games

- Advertisement

- Filters with triggers (raising eyebrows, tapping screen etc.)

Filters such as games and clearly humorous filters can be used for entertainment and enjoyment purposes, but beautification and surgery-based filters can be quite harmful.

Rebecca Coy-Dibley argues that ‘Western society’s booming beauty and sex industries have hyper-sexualised society, over-selling the female image as a currency and commodity of desire’ (2021, pg. 1).

She notes that social media has amplified this, as ‘not only do we critique our bodies in mirrors, but now we can digitize our dysmorphia by virtually modifying what we dislike, creating “perfect” selves instead’ (2021, pg. 1).

Research shows that filters have introduced a constant comparison of user’s real life features and how they ‘could’ look. This relationship has led to the new disorder of ‘digital dysmorphia’ which refers to ‘significant anxiety about [one’s] appearance’ (Coy-Dibley, 2021, pg. 3).

The video below explores individual’s struggle with social media, filters and their real-life appearance.

youtube

Human beings primal need to be loved also contributes to users’ unhealthy relationship with social media and filters. Research by Thomas Wagner et al found ‘approval [is] sought through engaging in extrinsically motivated performative behaviours. The extrinsic validation outweighs the intrinsic motivation to use social media just for fun’ (2021).

So next time you go on social media, remember everything you see is not the truth. I know it’s easier said than done, but try not to let social pressures make you feel bad about yourself and your appearance. Real life you is amazing!

References:

Barker, J 2020, Making-up on mobile: The pretty filters and ugly implications of Snapchat, Fashion, Style & Popular Culture, vol. 7, no. 2-3, <https://commons.swinburne.edu.au/file/56ce657d-9493-4f9c-9339-d020f7d522e9/1/2050-0726vol7no2-3pp207-221.pdf>

Global News 2019, Selfie Dysmorphia: How social media filters are distorting beauty, 25 July, viewed 25 April 2023, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tRfpuEXrJqQ&t=108s>

Coy-Dibley, R 2016, “Digitized Dysmorphia” of the female body: the re/disfigurement of the image, Palgrave Communications, vol. 2, https://www.nature.com/articles/palcomms201640

Wagner, T, Wolkins, K, Herman A 2021, Social Approval, Social Comparison and Digital Alterations on Instagram as Predictors of Image Fixation, The Journal of Social Media in Society, vol. 10, no. 2, Tarleton State University, <https://go.gale.com/ps/i.do?p=AONE&u=swinburne1&id=GALE%7CA690357161&v=2.1&it=r>

#mda20009#week8#digitalcommunities#socialmedia#filters#digitaldysmorphia#augmentedreality#selfiedysmorphia

0 notes

Text

Digital Citizenship and Software literacy: Instagram Filters

The increasing accessibility and normalisation of filters, defined as AR technology that enables virtual objects to be “superimposed upon or composited with the real world”, has produced a collective “Digitised Dysmorphia” within society (Azuma, 1997) (Coy-Dibley, 2016).

With Snapchat pioneering the way in 2015, the quick adoption of filters and advancements in visual technology by other social media apps including Instagram and Tiktok has intensified socially generated beauty standards for females.). Popular beauty filters typically lighten a user’s complexion and eyes, shrink their nose and contour/narrow their face, proving to be a reflection of our current cultural ideals (Barker, 2020). Limited to the “prescribed beauty norms” offered by software designers; a saturation of “stereotypical, white slim, able-bodied” and overtly westernized aesthetics dominate social media feeds, and have also “infiltrated fashion and advertising” (Coy-Dibley, 2016). Under the “guise of beautification”, cosmetic, fashion and wellness brands utilise AR technology and Photoshop to imply the desirability of their products, ultimately suggesting that a customer will appear the same way if they purchase from their brands (Barker, 2020).

Consequently, the implications of Photoshop and society’s hyper-fixation on the ‘Instagram’ standard of female body has had a widespread impact on the population, and though difficult to diagnose, it is believed that 1 in 50 australians suffer from Body Dysmorphic Disorder (ABC, 2019).

Viewed through a certain lens, one could argue that digital filters provide females with the agency to “express a self” that would be overlooked offline, yet they also “accentuate the disparity” between normal female bodies and the unattainable images woman feel they must embody, an issue that is especially poignant for women of colour (Coy-Dibley, 2016). Furthermore, Rettberg argues that filters are a way of “heightening our own daily experiences” wherein which a “de-familiarisation effect” occurs on the user once they have edited their image (Rettberg, 2014). However, the novelty of “digital adornment” is pervasive to the point where a ‘de-familiarity’ with one’s own appearance online has led to mass dissatisfaction and the previously mentioned phenomenon of ‘digitised dysmorphia’ (Barker, 2020).

Though the technological potential and advancements of AR and filtering applications have been celebrated for their ability to extend an individual’s sense of self and empower females in a post-feminist context, women should not have to “feel ugly” without a filter.

References

Azuma, R. (1997) “A Survey of Augmented Reality”, MIT Press Direct, vol.6, no.4, pp.355-385.

Barker, J. (2020) “Making-up on mobile: The pretty filters and ugly implications of snapchat, Fashion, Style & Popular Culture”, vol.7, no.2,3, pp. 207-221.

Coy-Dibley, I. (2016) ‘“Digitised Dysmorphia” of the Female Body: The Re/Disfigurement of the Image’ Palgrave Communications, pp. 1-9.

Jones, R. (2019). “Body dysmorphia: when you can't trust the way you see your own body”, ABC: Triple J [online].

Rettberg, J.W. (2014). “Filtered Reality, Seeing Ourselves Through Technology: How We Use Selfies, Blogs, and Wearable Devices to See and Shape Ourselves”, Palgrave Macmillan, London.

0 notes

Text

Digital Citizenship and Software Literacy: Instagram Filters

‘Digital Dysmorphia’, a term coined by Isabelle Coy-Dibley (2016) is defined as the altering of supposedly undesirable parts of the self through modification and supposed fixing of the visual or virtual appearance of an individual’s self through various apps. In her article, Coy-Dibley states that this term is shared with Body Dysmorphic Disorder (BDD) whereby, individuals are concerned with some aspect of their appearance that they consider ugly, unattractive or “not right” in some way. It is not difficult to see how the disorder has had on an impact on the digital space. In the advent of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States in 2020 and as social distance became practiced, ‘Facetune’, had generated an increase of 20% in the use of its app by users. The editing app turns your face and body into digital Play-Doh, to mold, pinch, and add volume wherever you want (Rodulfo, 2020). It is simple to conclude that this disorder is rampant globally and is an issue that will debated as social media use grows with every single year.

However, Coy-Dibley (2016) points out that this disorder not only affects women but also men. She quotes that “there has been a growing preoccupation with weight and body image in men, which parallels this increased ‘visibility’ of the male body.” Although not as evident as that of women, this can be seen in the engagement of physical activity by males in Australia. According to the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2019), they state that in the 2017–18 survey period, 50% of men aged 18 and over were sufficiently physically active and 1 in 4 men (25%) did strength or toning activities on 2 or more days. Moreover, 30% of Australians have a gym membership (Physical Activity Australia, 2019). Therefore, it has been demonstrated that although men do not often exhibit images that manipulate their image on social media. Although they do take efforts to improve their image such as going to the gym which I myself am currently attending often.

References

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2019, The health of Australia’s males, Australian Government, viewed 22 April 2021, < https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/men-women/male-health/contents/lifestyle-and-risk-factors/physical-activity>.

Coy-Dibley, I 2016, “Digitised Dysmorphia” of the Female Body: The Re/Disfigurement of the Image, Palgrave Communications.

Physical Activity 2019, Gyms and Fitness Centres in Australia – Market Research Report, Physical Activity Australia, viewed 22 April 2021, < https://www.physicalactivityaustralia.org.au/gyms-and-fitness-centres-in-australia-market-research-report/#:~:text=Around%2030%20per%20cent%20of,activities%20in%20full%2Dservice%20gyms.>.

Rodulfo, K 2020, How Face Filters on Instagram, Facetune Affect Mental Health, Women’s Health, viewed 22 April 2021, < https://www.womenshealthmag.com/beauty/a33264141/face-filters-mental-health-effect/>.

0 notes

Text

Digital Dysmorphia - The Consequences of Social Media Filters on Beauty Standards

If I were told I could only keep one social media platform on my phone and had to delete the rest, I would choose Instagram. I have had my account since I was twelve, and it’s the centre of my online self. I post my celebrations, my writing, photos with friends, a selfie if I’m feeling cute that day... It is the hub for my digital identity.

In saying that, it hasn’t always been a positive environment for me to exist in. Instagram has made me question my hair colour, my eye shape, my body type; my self-worth. I viewed the app as a tool for comparison and I wasn’t even aware of the implicit messaging I was subjecting my impressionable younger self to. Even to this day, I actively fight the narratives that were ingrained into my mind from the day I joined the app. The digitalisation of my life came with a consequence to the way I perceive not only myself, but other women too.

When I open Instagram, my goal is to see a feed that is fed by an algorithm that aligns with my values and interests. I was not aware that before I actively culled the accounts who operate to achieve an agenda other than an unfiltered, empowering or realistic online portrayal, I was consuming content that is designed to make me dislike the features or qualities that enhance uniqueness and instead crave a common, edited and aesthetic representation. Constructed to target my self-esteem and encourage the act of editing my appearance on apps such as Facetune or Photoshop, my body became a topic to compete with a “battlefield of diverging concepts, regulations, values and modifications” (Coy-Dibley, 2015, p. 2).

Social media trends are guaranteed to evolve and undergo constant reconstruction of what is deemed to be ‘beautiful’. Presenting an environment that leads users to conform to the current expectations placed on women is an exhaustive and archaic system to create, consume and exist in online. When an individual is persuaded to employ filters or editing software that modifies their bodies it is often paired with “complex feelings towards their natural beauty” (Barker, 2020, p. 212).

Comparatively, whilst body positivity has become a transformative and necessary trend that promotes self-love without the imposed societal pressures, it can also lead to an illusion of security based on external factors. It’s completely unrealistic to feel a constant positive outlook on body image. It’s human nature for us to experience ebbs and flows through the journey of relearning what is healthy and should be measured with care rather than comparison. The fine line and responsibility with body positivity is ensuring that it empowers you rather than inadvertently achieving the opposite.

Reference list:

Barker, J, (2020), 'Making-up on mobile: The pretty filters and ugly implications of Snapchat', Fashion, Style & Popular Culture, vol 7, no. 2.

Coy-Dibley, I, (2016), '“Digitized Dysmorphia” of the female body: the re/disfigurement of the image', Palgrave Communications, vol 2, no. 1.

0 notes