#eliot verse || you and me could write a bad romance

Text

@im-possiblelimits liked for a lyric starter (to kev, love ur husband)

“I really wish it was only me and you, I'm jealous of everybody in the room.”

#( source; first date // blink-182 )#eliot verse || you and me could write a bad romance#adfgjfgkbgf this came on and i just..........................

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

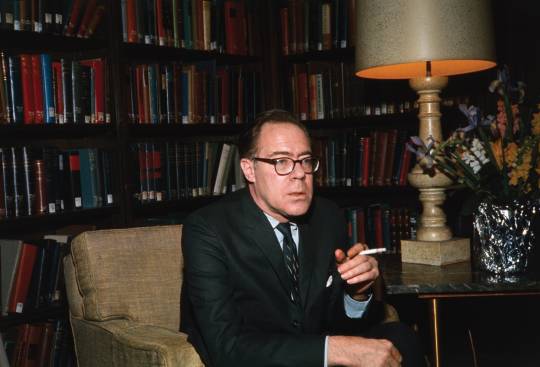

John Berryman in 1966, two years after the publication of “77 Dream Songs.”

The Heartsick Hilarity of John Berryman’s Letters is a book review by Anthony Lane (in The New Yorker) of The Selected Letters of John Berryman. The book is edited by Philip Coleman and Calista McRae and published by the Belknap Press, at Harvard. My acquaintance, the generous Philip Coleman, mailed me a copy of this book at the end of October.

Lane writes, “. . . anyone who delights in listening to Berryman, and who can’t help wondering how the singer becomes the songs, will find much to treasure here, in these garrulous and pedantic pages. There is hardly a paragraph in which Berryman—poet, pedagogue, boozehound, and symphonic self-destroyer—may not be heard straining toward the condition of music. ‘I have to make my pleasure out of sound,’ he says. The book is full of noises, heartsick with hilarity, and they await their transmutation into verse.”

Here is the book review:

The poet John Berryman was born in 1914, in McAlester, Oklahoma. He was educated at Columbia and then in England, where he studied at Cambridge, met W. H. Auden and Dylan Thomas, and lit a cigarette for W. B. Yeats. All three men left traces in Berryman’s early work. In 1938, he returned to New York and embarked upon a spate of teaching posts in colleges across the land, beginning at Wayne State University and progressing to stints at Harvard, Princeton, Cincinnati, Berkeley, Brown, and other arenas in which he could feel unsettled. The history of his health, physical and mental, was no less fitful and spasmodic, and alcohol, which has a soft spot for poets, found him an easy mark. In a similar vein, his romantic life was lunging, irrepressible, and desperate, so much so that it squandered any lasting claim to romance. Thrice married, he fathered a son and two daughters. He died in 1972, by jumping from the Washington Avenue Bridge in Minneapolis. To the appalled gratification of posterity, his fall was witnessed by somebody named Art Hitman.

Berryman would have laughed at that. In an existence that was littered with loss, the one thing that never failed him, apart from his unwaning and wax-free ear for English verse, was his sense of humor. The first that I heard of Berryman was this:

Life, friends, is boring. We must not say so.

After all, the sky flashes, the great sea yearns,

we ourselves flash and yearn,

and moreover my mother told me as a boy

(repeatingly) ‘Ever to confess you’re bored

means you have no

Inner Resources.’ I conclude now I have no

inner resources, because I am heavy bored.

Peoples bore me,

literature bores me, especially great literature,

Henry bores me, with his plights & gripes

as bad as achilles,

who loves people and valiant art, which bores me.

And the tranquil hills, & gin, look like a drag

and somehow a dog

has taken itself & its tail considerably away

into mountains or sea or sky, leaving

behind: me, wag.

“Wag” meaning a witty fellow, or “wag” meaning that he is of no more use than the back end of a mutt? Who on earth is Henry? Also, whoever’s talking, why does he address us as “friends,” as if he were Mark Antony and we were a Roman mob, and why can’t he even honor Achilles—the hero of the Iliad, a foundation stone of “great literature”—with a capital letter? You have to know such literature pretty well before you earn the right to claim that it tires you out. Few knew it better than Berryman, or shouldered the burdens of serious reading with a more remorseless joy. As he once said, “When it came to a choice between buying a book and a sandwich, as it often did, I always chose the book.”

“Life, friends” is the fourteenth of “The Dream Songs,” the many-splendored enterprise that consumed Berryman’s energies in the latter half of his career, and on which his reputation largely rests. His labors on the Songs began in 1955 and led to “77 Dream Songs,” which was published in 1964 and won him a Pulitzer Prize. In the course of the Songs, which he regarded as one long poem, he is represented, or unreliably impersonated, by a figure named Henry, who undergoes “the whole humiliating Human round” on his behalf. As Berryman explained, “Henry both is and is not me, obviously. We touch at certain points.” In 1968, along came a further three hundred and eight Songs, under the title “His Toy, His Dream, His Rest.” (A haunting phrase, which grabs the seven ages of man, as outlined in “As You Like It,” and squeezes them down to three.) Two days after publication, he was asked, by the Harvard Advocate, about his profession. “Being a poet is a funny kind of jazz. It doesn’t get you anything,” he said. “It’s just something you do.”

There was plenty of all that jazz. Berryman forsook the distillations of Eliot for the profusion of Whitman; the Dream Songs, endlessly rocking and rolling, surge onward in waves. Lay them aside, and you still have the other volumes of Berryman’s poems, including “The Dispossessed” (1948), “Homage to Mistress Bradstreet” (1956), and “Love & Fame” (1970). Bundled together, they fill nearly three hundred pages. If magnitude freaks you out, there are slimmer selections—one from the Library of America, edited by Kevin Young, the poetry editor of this magazine, and another, “The Heart Is Strange,” compiled by Daniel Swift to toast the centenary, in 2014, of the poet’s birth. And don’t forget the authoritative 1982 biography by John Haffenden, who also put together a posthumous collection, “Henry’s Fate and Other Poems,” in 1977, as well as “Berryman’s Shakespeare” (1999), a Falstaffian banquet of his scholarly work on the Bard. Some of Berryman’s critical writings are clustered, invaluably, in “The Freedom of the Poet” (1976). In short, you need space on your shelves, plus a clear head, if you want to join the Berrymaniacs. Proceed with caution; we can be a cranky bunch.

Of late, Berryman’s star has waned. Its glow was never steady in the first place, but it has dimmed appreciably, because of lines like these:

Arrive a time when all coons lose dere grip,

but is he come? Le’s do a hoedown, gal.

“The Dream Songs” is a hubbub, and some of it is spoken in blackface—or, to be accurate, in what might be described as blackvoice. It deals in unembarrassed minstrelsy, complete with a caricature of verbal tics, all too pointedly transcribed: “Now there you exaggerate, Sah. We hafta die.” To say that Berryman was airing the prejudices of his era is hardly to exonerate him; in any case, he seems to be evoking, in purposeful anachronism, an all but vanished age of vaudeville. Kevin Young, who is Black, prefaces his choice of Berryman’s poetry by arguing, “Much of the force of The Dream Songs comes from its use of race and blackface to express a (white) self unraveling.” Some readers will share Young’s generously inquiring attitude; others will veer away from Berryman and never go back.

For anyone willing to stick around, there’s a new book on the block. “The Selected Letters of John Berryman” weighs in at more than seven hundred pages. It is edited by Philip Coleman and Calista McRae, and published by the Belknap Press, at Harvard—a selfless undertaking, given that Berryman derides Harvard as “a haven for the boring and the foolish,” wherein “my students display a form of illiterate urbanity which will soon become very depressing.” (Not that other colleges elude his gibes. Berkeley is summed up as “Paradise, with anthrax.”) The earliest letter, dated September, 1925, is from the schoolboy Berryman to his parents, and ends, “I love you too much to talk about.” In a pleasing symmetry, the final letter printed here, from 1971, shows Berryman rejoicing in his own parenthood. He tells a friend, “We had a baby, Sarah Rebecca, in June—a beauty.”

And what lies in between? More or less the polyphony that you’d expect, should you come pre-tuned into Berryman. “Vigour & fatigue, confidence & despair, the elegant & the blunt, the bright & the dry.” Such is the medley, he says, that he finds in the poetry of Gerard Manley Hopkins, and you can feel Berryman swooping with similar freedom from one tone to the next. “Books I’ve got, copulation I need,” he writes from Cambridge, at the age of twenty-two, thus initiating a lifelong and dangerous refrain. When he reports, two years later, that “I was attacked by an excited loneliness which is still with me and which has so far produced fifteen poems,” is that a grouse or a boast? There are alarming valedictions: “Nurse w. another shot. no more now,” or, “Maybe I better go get a bottle of whisky; maybe I better not.” There are letters to Ezra Pound, one of which, sent with “atlantean respect & affection,” announces, “What we want is a new form of the daring,” a very Poundian demand. And there are smart little swerves into the aphoristic—“Writers should be heard and not seen”; “All modern writers are complicated before they are good”—or into courteous eighteenth-century brusquerie. Pastiche can be useful when you have a grudge to convey: “My dear Sir: You are plainly either a fool or a scoundrel. It is kinder to think you a fool; and so I do.” It’s a letter best taken with a pinch of snuff.

Berryman was a captious and self-heating complainer, slow to cool. Just as the first word of the Iliad means “Wrath,” so the first word of the opening Dream Song is “Huffy.” Seldom can you predict the cause of his looming ire. A concert performance by the Stradivarius Quartet, in the fall of 1941, drives him away: “Beethoven’s op. 130 they took now to be a circus, now to be a sea-chantey, & I fled in the middle to escape their Cavatina.” The following year, an epic letter to his landlord, on Grove Street, in Boston, is almost entirely concerned with a refrigerator, which has “developed a high-pitched scream.” Berryman was not an easy man to live with, or to love, and the likelihood that even household appliances found his company intolerable cannot be dismissed.

Yet the poet was scarcely unique in his vexations; we all have our fridges to bear. Something else, far below the hum of daily pique, resounds through this massive book—a ground bass of doom and dejection. “You may prepare my coffin.” “If this reaches you, you will know I got as far as a letter-box at any rate.” “I write in haste, being back in Hell.” Such are the dirges to which Berryman treats his friends, in the winter of 1939–40, and the odd jauntiness in which he couches his misery somehow makes it worse. It’s one thing to write, “I am fed up with pretending to be alive when in fact I am not,” but quite another to dispatch those words, as Berryman did, to someone whom you are courting; the recipient was Eileen Mulligan, whom he married nine months later, in October, 1942. To the critic Mark Van Doren, who had been his mentor at Columbia, he was more formal in his woe, declaring, “Each year I hope that next year will find me dead, and so far I have been disappointed, but I do not lose that hope, which is almost my only one.” We are close to the borders of Beckett.

There are definite jitters of comedy in so funereal a pose, and detractors of Berryman would say that he keeps trying on his desolation, like a man getting fitted for a dark suit. The trouble is that we know how he died. Even if he is putting on an act, for the horrified benefit of his correspondents, it is still a rehearsal for the main event, and you can’t inspect the long lament that he sends to Eileen in 1953—after they have separated—without glancing ahead, almost twenty years, to the dénouement of his days. The letter leaps, like one of those 3 a.m. frettings which every insomniac will recognize, directly from money to death. “I only have $2.15 to live through the week,” the poet says, before laying out his plans. “My insurance, the only sure way of paying my debts, expires on Thursday. So unless something happens I have to kill myself day after tomorrow evening or earlier.” To be specific, “What I am going to do is drop off the George Washington bridge. I believe one dies on the way down.” If Berryman is playing Cassandra to himself, crying out the details of his own quietus, how did the cry begin?

It is tempting to turn biography into cartography—unrolling the record of somebody’s life, smoothing it flat, and indicating the major fork in the road. Most of us rebut this thesis, as we amble maplessly along. In Berryman’s case, however, there was a fork, so terrible and so palpable that no account of him, and no encounter with his poems, can afford to ignore it. The road didn’t simply split in two; it was cratered, in the summer of 1926, when his father, John Allyn Smith, committed suicide.

The family was living in Clearwater, Florida, at the time, and young John was eleven years old. There was a bizarre prelude to the calamity, when his brother, Robert, was taken out by their father for a swim in the Gulf. What occurred next remains murky, but it seemed, for a while, as if they would not be returning to shore. One of the Dream Songs takes up the tale, mixing memory and denial:

Also I love him: me he’s done no wrong

for going on forty years—forgiveness time—

I touch now his despair,

he felt as bad as Whitman on his tower

but he did not swim out with me or my brother

as he threatened—

a powerful swimmer, to take one of us along

as company in the defeat sublime,

freezing my helpless mother:

he only, very early in the morning,

rose with his gun and went outdoors by my window

and did what was needed.

I cannot read that wretched mind, so strong

& so undone. I’ve always tried. I—I’m

trying to forgive

whose frantic passage, when he could not live

an instant longer, in the summer dawn

left Henry to live on.

Smith’s death would become the primal wound for his older son. Notice how the tough and Hemingway-tinged curtness of “did what was needed” gives way, all too soon, to the halting stammer of “I—I’m trying.” The wound was suppurating and unhealable, and there is little doubt that it deepened the festering of Berryman’s life. As he writes in one of the final Dream Songs, “I spit upon this dreadful banker’s grave / who shot his heart out in a Florida dawn / O ho alas alas.” Haffenden quotes these lines, raw with recrimination, in his biography; dryly informs us that the poet, in fact, never visited his father’s grave; and supplies us with relevant notes that Berryman made in 1970—two years before he, in turn, found a bridge and did what he thought was needed. He sounds like a patient striving mightily to become his own shrink:

Did I myself feel any guilt perhaps—long-repressed if so & this is mere speculation (defense here) about Daddy’s death? (I certainly pickt up enough of Mother’s self-blame to accuse her once, drunk & raging, of having actually murdered him & staged a suicide.)

Alternatively:

So maybe my long self-pity has been based on an error, and there has been no (hero-) villain (Father) ruling my life, but only an unspeakably powerful possessive adoring mother, whose life at 75 is still centered wholly on me. And my (omnipotent) feeling that I can get away with anything.

For readers who ask themselves, browsing through “Berryman’s Shakespeare,” why the poet bent his attention, again and again, to “Hamlet,” to the plight of the prince, and to the preoccupations—as Berryman boldly construed them—of the man who wrote the play, here is an answer of sorts. And, for anyone wanting more of this unholy psychodrama, consider the list of characters. Berryman’s mother, born Martha Little, married John Allyn Smith. Less than eleven weeks after his death, she married her landlord, John Angus McAlpin Berryman, and thereafter called herself Jill, or Jill Angel. As for the poet, he was baptized with his father’s name, was known as Billy in infancy, and then, in deference to his brand-new stepfather, became John Berryman. This is like Hamlet having to call himself Claudius, Jr., on top of everything else. As Berryman remarks, “Damn Berrymans and their names.”

A book of back-and-forth correspondence with his mother was published in 1988, under the title “We Dream of Honour.” (Having picked up the habit of British spelling, at Cambridge, Berryman never kicked it.) Inexcusably, it’s now out of print, but worth tracking down; and you could swear, as you leaf through it, that you’d stumbled upon a love affair. The son says to the mother, “I hope you’re well, darling, and less worried.” The mother tells the son, “I have loved you too much for wisdom, or it is perhaps nearer truth to say that with love or in anger, I am not wise.” We are offered a facsimile of a letter from 1953, in which Berryman begins, “Mother, I have always failed; but I am not failing now.”

One obvious shortfall in the “Selected Letters” is that “We Dream of Honour” took the cream of the crop. Only eight letters here are addressed to Martha, six of them mailed from school, and, if you’re approaching Berryman as a novice, your take on him will be unavoidably skewed. By way of compensation, we get a wildly misconceived letter of advice from the middle-aged Berryman to his son, Paul, concluding with the maxim “Strong fathers crush sons.” Paul was four at the time. Haffenden has already cited that letter, however, and doubts whether it was ever sent. One item in the new book that I have never read before, and would prefer not to read again, is a letter from the fourteen-year-old Berryman to his stepfather, whom he calls Uncle Jack, and before whom he cringes as if whipped. “I’m a coward, a cheat, a bully, and a thief if I had the guts to steal,” the boy writes. Things get worse: “I have none of the fine qualities or emotions, and all the baser ones. I don’t understand why God permitted me to be born.” He signs himself “John Berryman,” the sender mirroring the recipient, and adds, “P.S. I’m a disgrace to your name.”

To read such words is to marvel that Berryman survived as long as he did. If one virtue emerged from the wreckage of his early years, it was a capacity to console; later, in the midst of his drinking and his lechery, he remained a reliable guide to grief, and to the blast area that surrounds it. In May, 1955, commiserating with Saul Bellow, whose father has just passed away, Berryman writes, “Unfortunately I am in a v g position to feel with you: my father died for me all over again last week.” He unfolds his larger theme: “His father’s death is one of the few main things that happens to a man, I think, and it matters greatly to the life when it happens.” Bellow’s affliction, Berryman reassures him, lofts him into illustrious company: “Shakespeare was probably in the middle of Hamlet and I think his effort increased.” Freud and Luther are then added to the roster of the fruitfully bereaved.

None of this will surprise an admirer of the Dream Songs. Among the loveliest are those in which the poet mourns departed friends, such as Robert Frost, Louis MacNeice, Theodore Roethke, and Delmore Schwartz. Berryman the comic, who can be scabrously funny, not least at his own expense, consorts with Berryman the frightener (“In slack times visit I the violent dead / and pick their awful brains”) and Berryman the elegist, who can summon whole twilights of sorrow. In this, a tribute to Randall Jarrell, he gradually allows the verse to run on, like overflowing water, across the line breaks, with a grace denied to our harshly end-stopped lives:

In the night-reaches dreamed he of better graces,

of liberations, and beloved faces,

such as now ere dawn he sings.

It would not be easy, accustomed to these things,

to give up the old world, but he could try;

let it all rest, have a good cry.

Let Randall rest, whom your self-torturing

cannot restore one instant’s good to, rest:

he’s left us now.

The panic died and in the panic’s dying

so did my old friend. I am headed west

also, also, somehow.

In the chambers of the end we’ll meet again

I will say Randall, he’ll say Pussycat

and all will be as before

when as we sought, among the beloved faces,

eminence and were dissatisfied with that

and needed more.

A photograph of 1941 shows Berryman in a dark coat, a hat, and a bow tie. His jaw is clean-shaven and firm. With his thin-rimmed spectacles and his ready smile, he looks like a spry young stockbroker on his way home from church. Skip ahead to the older Berryman, and you observe a very different beast, with a beard like the mane of a disenchanted lion. Finches could roost in it. The rims of his glasses are now thick and black, and his hands, in many images, refuse to be at rest. They gesticulate and splay, as if he were conducting an orchestra that he alone can hear. A cigarette serves as his baton.

If you seek to understand this metamorphosis, “The Selected Letters of John Berryman” can help. What greets us here, as often as not, is a parody of a poet. Watch him fumble with the mechanisms of the everyday, “ghoulishly inefficient about details and tickets and visas and trains and money and hotels.” Chores are as heavy as millstones, to his hypersensitive neck: “Do this, do that, phone these, phone those, repair this, drown that, poison the other.” We start to sniff a blend—peculiar to Berryman, like a special tobacco—of the humbled and the immodest. It drifts about, in aromatic puns: “my work is growing by creeps & grounds.” Though the outer world of politics and civil strife may occasionally intrude, it proves no match for the smoke-filled rooms inside the poet’s head. When nuclear tests are carried out at Bikini Atoll, in 1954, they register only briefly, in a letter to Bellow. “This thermonuclear business wd tip me up all over again if I were in shape to attend to it,” Berryman writes, before moving on to a harrowing digest of his diarrhea.

Above all, this is a book-riddled book. No one but Berryman, it’s fair to say, would write from a hospital in Minneapolis, having been admitted in a state of alcoholic and nervous prostration, to a bookstore in Oxford, asking, “Can you let me know what Elizabethan Bibles you have in stock?” The recklessness with which he abuses his body is paired with an indefatigable and nurselike care for textual minutiae. (“Very very tentatively I suggest that the comma might come out.”) Only on the page can he trust his powers of control, although even those desert him at a deliciously inappropriate moment. Writing to William Shawn at The New Yorker, in 1951, and proposing “a Profile on William Shakespeare,” Berryman begins, “Dear Mr Shahn.” Of all the editors of all the magazines in all the world, he misspells him.

No such Profile appeared; nor, to one’s infinite regret, did the edition of “King Lear” on which Berryman toiled for years. What we do have is his fine essay of 1953, “Shakespeare at Thirty,” which begins, “Suppose with me a time, a place, a man who was waked, risen, washed, dressed, fed, on a day in latter April long ago—about April 22, say, of 1594, a Monday.” Few scholars would have the bravado, or the imaginative dexterity, for such supposings, and it’s a thrill to see a living poet treat a dead one not as a monument but as a partner in crime. “Oh my god! Shakespeare. That multiform & encyclopedic bastard,” Berryman says in a letter of 1952, as if the two of them had just locked horns in a tavern.

Such plunges into the past, with its promise of adventure and refuge, came naturally to Berryman, nowhere more so than in “Homage to Mistress Bradstreet,” which was published in the Partisan Review in 1953 and, three years later, as a book. This was the poem with which he broke through—discovering not just a receptive audience but a voice that, in its heightened lyrical pressure, sounded like his and nobody else’s. The irony is that he did so by assuming the role of a woman: Anne Bradstreet, herself a poet, who emigrated from England to America, in 1630. It is her tough, pious, and hardscrabble history that Berryman chronicles: “Food endless, people few, all to be done. / As pippins roast, the question of the wolves / turns & turns.” In a celebrated scene, the heroine gives birth. Even if you dispute the male ability (or the right) to articulate such an experience, it’s hard not to be swayed by the fervor of dramatic effort:

I can can no longer

and it passes the wretched trap whelming and I am me

drencht & powerful, I did it with my body!

One proud tug greens Heaven. Marvellous,

unforbidding Majesty.

Swell, imperious bells. I fly.

What the poem cost its creator, over more than four years, is made plain in the letters, which ring with an exhausted ecstasy. “I feel like weeping all the time,” he tells one friend. “I regard every word in the poem as either a murderer or a lover.” As for Anne, who perished in 1672, “I certainly at some point fell in love with her.” Berryman adds, as if to prove his devotion, “I used three shirts at a time, in relays. I wish I were dead.”

Is this how we like poetry to be brought forth, even now? Though we may never touch the stuff, reading no verse from one year to the next, do we still expect it to be delivered in romantic agony, with attendant birth pangs? (So much for Wallace Stevens, who composed much of his work while gainfully employed, on a handsome salary, as an insurance executive.) Berryman viewed the notion of his being a confessional poet “with rage and contempt,” and rightly so; the label is an insult to his craftsmanship. Nobody pining for mere self-expression, or craving a therapeutic blurt, could lavish on a paramour, as Berryman did, lines as elaborately wrought as these:

Loves are the summer’s. Summer like a bee

Sucks out our best, thigh-brushes, and is gone.

You have to reach back to Donne to find so commanding an exercise in the clever-sensual. It comes from “Berryman’s Sonnets,” a sequence of a hundred and fifteen poems, published in 1967. Most of them had been written long before, in 1947, in heat and haste, during an affair with a woman named Chris Haynes. And, in this huge new hoard of letters, how many are addressed to Haynes? Precisely one. Gossip hunters will slouch off in frustration, and good luck to them; on the other hand, anyone who delights in listening to Berryman, and who can’t help wondering how the singer becomes the songs, will find much to treasure here, in these garrulous and pedantic pages. There is hardly a paragraph in which Berryman—poet, pedagogue, boozehound, and symphonic self-destroyer—may not be heard straining toward the condition of music. “I have to make my pleasure out of sound,” he says. The book is full of noises, heartsick with hilarity, and they await their transmutation into verse.

1 note

·

View note

Text

12 Books that Changed Me in 2016

The trouble, of course, with reading a good book is that there is always another one lurking around the corner. Now that I've had a couple of months away from the last year, I feel confident that I can point to the books that actually changed my year in 2016. There were a few essays and short stories that re-opened my eyes to the world around me, but I've decided to stick with full-length books out of simplicity. Also, there's not any order to this list; some of these books I believe I'll re-read a hundred times, and others I plan on letting go. What is important, above all, is that I think we should all be reading more things, and hearing more voices, and listening better, and these books have made me better at that kind of sensitivity in some small way. I thought that I should avoid being gushy - for a minute - and then I decided I'd rather gush about these books. This is my reading testimony, not reviews. With that said...

Bird By Bird - Anne Lamott

Most writers read this book - and that's not uncommon. There are a few books that we all have to read to understand what it is that we do. Very few books are the kind that I immediately turn around and recommend to others. If you've ever wanted to make something, read this book, or at the very least, the first two sections, which can be found in PDF form here.

Operating Instructions - Anne Lamott

When I make these sorts of lists, I do my best to avoid including the same author twice, but that's just too bad this time around. If Bird by Bird is the writer's guide to writing, Operating Instructions was my guide out of a very dark place. It came to me at just the right time, and I'm grateful. It tells Lamott's own story of having her son and losing her best friend in the same year. It is heart-wrenching in the sense that it stretches your heartstrings: they can now play music again.

If on a winter's night a traveler - Italo Calvino

This book blasted open the edges of what a story can and cannot do. If you think you know how books work (as in, how they must and always work), I would humbly suggest this particular book, in which you will fall in love and see story in a whole new light.

The Cocktail Party - T.S. Eliot

This is a play in verse that explores the ability of the sacred to invade the most ordinary of situations. It's what I needed to know could exist to become the kind of writer I'll be one day.

Gilead - Marilynne Robinson

Stories written as epistles aren't uncommon. What is rare is the delicate kindness with which Marilynne Robinson explores the depths of her main character's soul. Like Anne Lamott, she asks questions of faith that may not have easy answers, but does so in an entirely different mode - an aging preacher with a young son - instead of an autobiographical account. There are three books (so far) that take place in the town of Gilead, and I recommend all of them.

Civilwarland in Bad Decline - George Saunders

This is a series of interconnected short stories that will make you question America, whether you are a liberal or conservative or somewhere in between. The book is not even political so much as it is personal: what kind of ordinary, decent people experience disaster, and how does it change them? Do they recover? How? This is a book I'm going to read again.

A River Runs Through It - Norman Maclean

Of all the books I've read in prose, this is the one that comes the closest to reading like poetry. It is a book that merits reading by a fireplace. Rather than explain what this book is "about," know that it is a story that will show you a river, fly fishing, family, and love in a light that is always fresh, because it is always true.

All Involved - Ryan Gattis

Remember what I said about listening to different voices a few lines up? Try listening to 17 first-person narrators telling their stories through the horror of the Rodney King riots. If you follow my blog, you know this book has come up over and over, and it is because it is a book that will make you look through eyes that are often shut too young, shut down, and silenced by violence against either the bodies they inhabit or the words those bodies say.

Little Bee - Chris Cleave

This book and All Involved came to me at the same time and from the same person - needless to say, I'm grateful. It's a hard book to explain without giving anything away, but once again, this is a book that will reach your core.

Nine Horses - Billy Collins

Billy Collins is a great poet of the ordinary things in life. I've read individual poems before, but last year, I finally read a book of his and was blown away by its simple exploration of an ordinary life, and how well he sustains this love of life through the ups and downs of his ordinary joys and losses. There is a reason he was the Poet Laureate of the United States. Now I know it.

Bandersnatch - Diana Pavlac Glyer

Wanna know how collaboration works? Read this and learn from the Inklings, one of the greatest groups of writers of all time. If you'd like to know more, check I will refer to the original review I wrote about Bandersnatch last year, which can be found here.

Romance's Rival: Familiar Marriage in Victorian Fiction - Talia Schaffer

Academic books rarely make it easier to read source texts. Sure, there are basic explanatory notes, but interpretations are not always helpful for the reader (as opposed to the scholar). This book was an exception; it made it easier and, in fact more enjoyable, to read Victorian fiction. While I might not recommend actually reading this book to everyone, I was pleasantly surprised by how helpful Schaffer's book was.

0 notes

Note

“I wish we knew each other sooner.” //all the hubby feels

late nights / accepting / @im-possiblelimits, for kevin, who we love dearly

Eliot gives him a soft smile, though he’s only about half sure Kevin can see it in the dark. They’re both laying on their back, exhausted because of activities that people sometimes do in the dark, but Eliot turns his body and props up his head on his hand (and uses his free hand to gently run over Kevin’s chest.) “I do too. We both spent a lot of time very unhappy,” he answers quietly, leaning to steal a kiss. “What would you have done, if you woke up one day and found yourself in a school for what is essentially wizardry?”

#i'm selfish and wanted more of them talking about magic lol#thank you so much i love this#im possiblelimits; kevin#eliot verse || you and me could write a bad romance#im-possiblelimits

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

@im-possiblelimits / from here

it was taking every ounce of control & self preservation that kevin has to keep himself from crumpling into a ball as eliot yelled. he isn’t sure if it’s aimed at him or if eliot’s just loudly airing out his frustrations, but kevin can barely handle it. if he was drunk right now, this would be so much easier to handle. somehow, though, he manages to muster up enough energy to tell eliot to stop & thankfully he does.

shoulders relax as eliot shifts out of his aggressive stance & sits on the couch next to him, no longer feeling like he’s being attacked, & leans back against the couch, letting out a calming breath. he’s quiet as eliot calmly explains what got him so worked up, & he isn’t entirely surprised; kevin’s in a very similar position. “i’m not exactly a fan of the press, either,” he offers up in agreement, hand running through his hair just to have his hands doing something. “just…don’t yell at me, alright? we’re not going to get very far with anything if you keep that up.”

he’s silent for a moment, thinking over eliot’s words. it’s the off season so it’s not like kevin can’t go with him….it’s more a matter of does he want to, or if it’s a good idea. for a variety of reasons. kevin shakes his head at himself, knocking all those thoughts away. “i don’t have anything i can’t miss going on right now. if you want….we can go to new york for a couple days… getting out of town is probably a good idea for both of us right now…”

Eliot makes a mental note to do better, because regardless of what happened they were stuck together for a very long time and the less hurt that either of them caused to each other during it, the better. It helps that he knew already that Kevin was respectful of his boundaries (and really, he should have predicted that Kevin would have boundaries about this too, but hindsight’s 20/20 and all.) He nods, “Noted, I’m sorry again for that. None of what I’m upset about is your fault to start with, and regardless it won’t happen again.”

The idea of going back to New York, paradoxically, has him even more stressed than the weight of the amount of time spent away from it. Eliot holds back for a moment though, because Kevin isn’t a mind reader and--this, after all, is about what he needs.

“That would be really nice,” Eliot smiles a little bit, looking to Kevin, “I’m rethinking New York though--I think I need someplace I can breathe a little bit easier. Plus I’m sure the press would have a field day. What do you think of someplace by the ocean? Seaside towns are so cute. It’ll be a good place for you to recover from all your working out, too.”

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

“ stop yelling! ” //idk what the hubs could be fighting about, but kev doesn't do well when he's being yelled at anywhere that isn't on the court

angsty meme / accepting always i love Pain / @im-possiblelimits

Eliot doesn’t want to stop yelling--there was a lot that he didn’t want to be doing right now and having gone weeks without his regular bed, or his Bambi, or being touched, or Quentin.

(He had been trying really hard not to think about everything that last one was making him feel.)

Truthfully, Eliot can’t even remember what they were fighting about because this past week had just been nonstop. That piled onto not getting the affection and attention that he needed, piled further onto his tendency to just bottle shit up made this a perfect storm.

At Kevin’s request he sighs, the words grounding him because Kevin’s right and yelling isn’t going to fix anything even if it feels sort of good to have an outlet now. He remembers their first morning together, how Kevin stopped on a dime because he’d inadvertently made Eliot uncomfortable, and rubs his hands over his face. “Sorry,” he sighs deeply, moving to the couch beside him to break himself out of his aggressive stance. Right, the matter at hand. “I’m just burned out by all this press, I’m missing New York, and I’m really bad at asking for the things I need. It’s not fair of me to take it out on you, and I will do better with that set of baggage. So if I can start over, I--mentally, need a couple of days off. It’d be nice to not be alone but I know you have things you need to do.”

#im possiblelimits; kevin#// in which el functions about as well as i do on burnout mode >>#eliot verse || you and me could write a bad romance

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

@im-possiblelimits / ft. eliot & daddishness

It was a rare moment of quiet--Eliot had gotten his designs finished and finalized about a week ahead of schedule, meaning he had some time in and around the office to catch up on more tedious tasks while he waited for the others on the boards to be ready for execution.

Eliot had been dicking off on the internet in his office when one of his favorite work people--his make up artist--came in with his almost-four year old son and started with “I am so sorry to even consider asking you this but I trust you more than anyone...” and ended with profuse thank yous and Eliot with a toddler in his lap.

They had done some coloring and now Eliot was walking with the little one around, showing him the massive windows overlooking the water. He didn’t even hear Kevin’s text saying he was on his way, quietly enamored instead with the forty pounds of baby in his arms. “What’s that?” Eliot asked, pointing out towards the water.

A huge grin, “Boats!”

“That’s right! And what noise does that guy down there make?” He pointed to someone walking their golden retriever. The child smiled again and did his best bark imitation, garnering more praise from Eliot.

#im possiblelimits; kevin#// u wanted cute ur GETTIN CUTE BUD !!!! ♥#eliot verse || you and me could write a bad romance

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

kevin wanted el in tHAT outfit and frankly who the fuck am i to deny him??? / @im-possiblelimits

Eliot knew right away when Kevin saw him in the outfit, he’d have to take it home with him so of course he does. A few things had inspired him to put it on today, maybe a week later, namely the playful flirting they’d been engaging in over text while Kevin was running errands.

When he sees Kevin come in through the door, he smirks to himself and adjusts his jacket to make his (decorated) shirtlessness all the more obvious, “You’re home early,” he says with a little flourish, “and you look just as good as when you left.”

#eliot verse || you and me could write a bad romance#im possiblelimits; kevin#icon made from the linked set because obviously i Need a pic of that

26 notes

·

View notes

Note

👌//@ el, love hubs

drunk confessions! / accepting / @im-possiblelimits

“Do not, under any circumstances, tell any of them I said this except maybe Nicky because he loves me anyway and maybe Allison because she probably already knows,” his tone is light; he’s had some bubbles and Eliot’s feeling...bubbly.

He presses a kiss to the top of Kevin’s head, staying close to him. “I really love your friends. I know I’m still new to them and some of them are still...unsure about me. But all of them are among some of the most amazing people I’ve ever met, and I feel crazy lucky to be married to you for so many reasons but that’s such a nice side effect.”

#// partially inspired by our convo earlier but i just#my heart is so full for el loving kevin's friends & their protective tendencies#bc kev absolutely deserves it and he's so happy that other people see that#eliot verse || you and me could write a bad romance#im-possiblelimits

1 note

·

View note

Note

💌 //love hubs

send for a sext ♥ accepting ♥ @im-possiblelimits

[ Kevin 🍆💋 ]: i put it on and i got hard instantly. nsfw incoming ;)

[ Kevin 🍆💋 ]:[insert a teasing-short video of Eliot, wearing this because of course, gracefully palming himself over his pants (which are low enough to reveal a good portion of his tattoo) and very faintly, an “Oh, my Queen...” can be heard]

1 note

·

View note

Note

What is your muse’s favorite place(s) to be touched? How does your muse approach one-night stands versus long term partners? What is a fantasy your muse has? What is one sexual insecurity that your muse has? //for el

sinday meme !! accepting !! @im-possiblelimits

What is your muse’s favorite place(s) to be touched? He loves being touched and kissed on the inner thighs, and also gripped (kinda roughly) on his hips. It’s rare that he actually thinks about either of these things enough to ask for them (unless he’s with someone inexperienced and he’s moving their hands around a la ‘touch me like this, yeah’) but once whoever he’s with actually does it, it brings out all sorts of nice noises from him ;)

How does your muse approach one-night stands versus long term partners? So Eliot doesn’t intentionally look for, much less do, long-term partners (part of why waking up married to Kevin fucked him up badly enough to like...actually stick with it lmao.) He very much prefers a one (or two) and done type of thing with the occasional acquaintances-with-benefits thing that doesn’t last more than a month or so. This is on purpose; he’s afraid of getting attached to someone who’s either going to bail on him or turn out to be absolutely terrible, and he’s also deeply afraid of being vulnerable and having that be used against him. Eliot carries a lot of self-loathing and worries that someone he falls for is going to see him the way he sees himself and leave, so he either doesn’t let anyone in or runs as soon as things start getting serious. He tends to find a lot of comfort in one night stands, whereas for quite a while the idea of serious dating was enough to give him hives.

What is a fantasy your muse has? Okay so it’s kinda Bad, Eliot’s most fantasized-about scenario with Kevin involves the two of them at some boringass party thing, it’s late and everyone’s drunk except them, and Kevin’s hand is creeping up his thigh but only just so because people. So Eliot whispers something in French right into his ear that’s very, very raunchy and Kevin gives him a look that just about makes his heart stop and whisks him away to the coat closet to, er, teach him a lesson.

What is one sexual insecurity that your muse has? He used to be really insecure about his body in general, though now not so much. It’s very easy to make him moan, and sometimes he wishes he could be a little more hard-to-get. His default tastes also tend to run fairly vanilla despite having a lot of experience with a lot of different kinks, and I think he wishes he was maybe a little more into the harder-core stuff (though honestly, that definitely fades by the time he’s out of brakebills.)

#eliot || headcanon#im possiblelimits#verse || you and me could write a bad romance#(bc relevant)#muse || eliot#im-possiblelimits

1 note

·

View note

Conversation

Interviewer: What's the best thing about living with Kevin?

Eliot, like 5 years into their marriage: Hmm.

Eliot: I never have to worry about not being able to open jars. That's nice.

Interviewer: What's the worst thing?

Eliot: I have half a dozen open jelly jars in the fridge because I really like having him do stuff for me and watching him flex.

Eliot: I don't even like jelly.

#// i'm so sorry i just.................couldn't stop thinking about this bc HE WOULD.#eliot verse || you and me could write a bad romance#eliot & kevin || light will fade & i will stay here with you

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

...[he] never asked me once about the wrong i did

// an aesthetic board starring vegas husbands eliot & kevin, for the lovely wonderful @im-possiblelimits ♥ [so many heart eyes] !!

#// wo.rk song owns me pal i'm sorry not sorry xD#eliot verse || you and me could write a bad romance#eliot & kevin || light will fade & i will stay here with you

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Series of Nice Things bc We Deserve Them

Set in Eliot's 'I got drunk married to a sports superstar wat do' verse, co-starring aftg's Kevin Day but honestly if you’re just looking for some Nice Eliot & Quentin content after that dumpster fire of a finale, i welcome you with open arms;; verse tag is here, the tl;dr is el accidentally marries a Very Famous Sports Guy while drunk in vegas and shenanigans ensue and they fall in love for real. dedicated ofc to @im-possiblelimits ♥

The 'what am I fucking doing for the rest of my life if magic never comes back' fear comes creeping back on him.

He and Kevin have multiple important conversations.

Kevin Day gives the best fucking pep talks ever. Eliot walks away from every hard conversation with him wondering how he got so lucky.

Eliot becomes a fashion designer

And hes fahcking BALLER at it !!!!!!!

He collaborates with Margo for a few collections; they become instant classics.

Margo models in like every show.

Eliot watches in Absolute pride.

Frankly???? El designs all his dresses for her specifically.

Routinely he either flies Quentin and Margo out to Chicago or goes to New York and crashes on Margo's couch.

Obviously Margo and Q stay in The Condo, in Eliot's old room which still houses a good portion of his stuff.

Once he starts raking in that Goöd designer cash, he gets them both stupid expensive gifts just cause.

"Eliot this bikini top is made from Swarovski fucking crystal"

"Eliot I CAN'T accept this case of Moët"

........"please just let me love you :( "

Of fuckin COURSE he gets box seats to a T Swift concert & takes Q along.

"How did you...?" "I'm making her a dress. Oh yeah, we're meeting tomorrow to consult and you're coming with." " .O."

This hurts extra good and cozy bc when Eliot moves from NY he makes Q promise him to always text him a singular emoji if he feels Bad(TM).

Eliot tells him that he doesn't care what time it is or what he has going on or even how bad Q feels, he'll drop just about anything.

El always texts back asking if hes up for a phone call. Usually he is; cue Eliot gently asking about what he ate last, how much he's slept, if he's taken his meds.

One time Q's completely despondent and Eliot starts racking his brain on what the next question should be when it just.......comes out of his mouth;;

I stay out too late. Got nothing in my brain. That's what people say...

"...I had no idea you knew that song."

Kevin totally hears him but thinks better of ever saying anything about it.

Margo however razzes the hell out of him (only lovingly)

Suddenly its Eliot taking Kevin to events instead of vice versa and everyone loves him

Eliot does some of his best sketch work at Kevin's practices.

Just practices tho, games are too high stakes and theres too many people around.

He always makes jokes at the end of the season about it being the end of the season for him too bc of that.

Eliot does try very very hard to balance attending exy games & practices and his own shit.

He's way more willing to go to a game than go to an event alone; he'd so much rather go with Kevin especially as he cuts his drinking back to almost nothing.

The exceptions tend to be when Margo (and Q) are in town. He's been known to bring them both.

Since its years later and his romantic feelings for Q are p much buried he gets a special kind of resentful about the fact that he can't just take Q to an event without it being An Issue(TM).

Even when it's the 3 of them, rumors fly. Eliot's extra conscious of his body language at that point and hates that he has to be.

He gets completely mortified one day bc of a hickey-slip that the press asks Kevin about.

"We think Q left it, what do you have to say?"

Kevin, raising his eyebrows: "No that was definitely me...."

Eliot, putting his head in his hands: "Ohhhhh my god....." -Can we get back to politics (please?)-

Q thinks the rumors are kind of funny He gets asked about it and hes just like "you've SEEN Kevin, right? Like......there's no competing with that, El's a lucky guy."

Really who doesn't think Kevin's hot?????? ofc Q’s not immune

Idk how but through sheer force of will Q and Kevin become friends

(or at least friendly-ish, which for Kevin? Fucking huge.)

Like obviously its nowhere near the level of friendship between Eliot and Q but Somethin noice happens there however many years later.

Q goes thru a bad breakup sometime down the line. Eliot asks Kevin if it's okay to fly him in.

Kevin patiently tells him that he doesn't need to ask that anymore.

Eliot's floored bc hes never actually been with a guy who was so secure????? It gives him a lot of feelings about being trusted and loved and accepted for who he is and how he expresses his affection.

Idk all I can think of is it being like Friday night and the 3 of them are on the couch together.

Q's sad and sleepy, his head on Eliot's lap, barely registering the Buffy episode El put on. Eliot's leaning against Kevin's shoulder, one hand holding his and the other absently playing with Q's hair, snarking lovingly every few minutes about the campiness.

Q apologizes to Kevin privately later on because oh god his head was just in his husband's lap and that's Super Weird, sorry....

That's probably about the time Kevin decides earnestly that Q's alright.

Idk how but SOMEHOW Eliot's left with a toddler for a minute and we all cry together in this chili's

I decided its Q's, let Q be a dad tbh. He's together with Eliot's makeup artist who was a single father before Q came into their lives.

Anyway Eliot’s sketching--like always. He hands over his notebook for color palette planning and a few colored pencils. "You wanna color with me?"

Everything's fine until bab starts Screamin.

(Gentle voice) "What's wrong?" [Screaming] "You hungry?" [No.] "Are you thirsty?" [No] "Are you tired?" [Soft affirmative noises] "Let's take a little nap then."

Eliot just picks bab up with so much care and love in his eyes, holding them gently and off on a mission to find either a guardian or a soft reclining chair.

Kevin witnesses all of this and is probably pretty sure he's never seen anything more wholesome in his damn life.

Kevin's most likely the one who suggests kids (I'm guessing he's retired)

Eliot probably would have but he just doesn't even think about it?? And then Kevin says in so many words that he'd be a good father and Eliot just about loses it

I can't decide if their kid's definitely a jock or definitely not a jock. Maybe they're a dancer?

Regardless, they're both endlessly supportive

Eliot of fucking Course joins the PTA.

His gym buddies flip their collective shits.

He's really out here advocating for good sex ed & preserving arts in schools bc hes a fuckin hero

Also family vacations to Everywhere but especially beachy places!!

#the magicians#eliot waugh#quentin coldwater#special focus on q because honestly that boy needs nice things and i'd give him all of them if i could#eliot verse || you and me could write a bad romance#eliot & kevin || light will fade & i will stay here with you#eliot said fuck canon so ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

// things that kill me absolutely completely dead; kevin calling eliot ‘mo rí‘

#eliot verse || you and me could write a bad romance#it kills el dead too#i'm here i'm queer i have a bottle of wine and it's MARCH TWENTY-SECOND#*pours one out 4 mcr*

3 notes

·

View notes