#elizabeth casteen

Text

Women’s History Meme || Empresses (2/5)

↬ Catherine de Valois-Courtenay (before 15 April 1303 – October 1346)

The official Neapolitan investigation into Andrew of Hungary’s murder targeted Johanna’s closest supporters and left her isolated and vulnerable. Her aunt, Catherine of Valois, took advantage of that vulnerability to become the queen’s confidant in order to make certain that one of her sons would be Naples’s next king. At first, it appeared that this son would be Robert, the eldest of the Tarantini, who for a time seemed to be winning the competition between the Angevin princes for power and whom Johanna requested a papal dispensation to marry. Soon, however, Louis gained the upper hand, and Johanna’s requests for dispensations began to identify him as her intended.

— From She-Wolf to Martyr: The Reign and Disputed Reputation of Johanna I of Naples by Elizabeth Casteen

Of the many relatives who chose to avail themselves of the glittering social whirl of the capital, one stood out: Joanna’s aunt, Catherine of Valois, widow of Robert the Wise’s younger brother Philip, prince of Taranto. Catherine was Joanna’s mother’s older half-sister (both were fathered by Charles of Valois). Catherine had married Philip in 1313, when Philip was thirty-five and she just ten. Catherine was Philip’s second wife. He had divorced his first on a trumped-up charge of adultery after fifteen years of marriage and six children in order to wed Catherine, who had something he wanted. She was the sole heir to the title of empress of Constantinople.

… Catherine was twenty-eight years old, recently widowed, and a force to be reckoned with when the newly orphaned Joanna and her sister, Maria, first knew her at the Castel Nuovo in 1331. Shrewd, highly intelligent, and vital, Catherine was supremely conscious of her exalted ancestry and wore her title of empress of Constantinople as though it were a rare gem of mythic origin. Even the death of her husband, Philip, in 1331 had not dissuaded her from persisting in her efforts to reclaim the Latin Empire for herself and her three young sons: Robert, Louis, and Philip. A series of shockingly inept leaders had left the Byzantine Empire vulnerable to attack from the west, and this state of affairs was well known in Italy. Moreover, Catherine was used to getting her way.

— The Lady Queen: The Notorious Reign of Joanna I, Queen of Naples, Jerusalem, and Sicily by Nancy Goldstone

#women's history meme#historyedit#catherine of valois#house of valois#capetian house of anjou#medieval#french history#italian history#european history#women's history#history#nanshe's graphics

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

my proposed Johanna I of Naples TV show: The She-Wolf of Naples

hello. one of my historical woman fixations is late medieval queen Johanna I of Naples (Giovanna I), who ruled the kingdom of Naples (in what is now modern day Italy) from 1343-1382.

Johanna’s grandfather was the legendary Robert the Wise, called so for his role as a patron of the arts, knowledge, and his efforts to transform Naples into a peaceful, beautiful city.

orphaned at a young age, Johanna was largely raised by her step-grandmother, Sancia of Majorca, who had no children of her own. she was acclaimed as Robert’s heir, as both his legitimate sons died young, and betrothed to her cousin Andrew of Hungary, who some argued had his own claim to the throne of Naples.

nevertheless, Robert insisted that Johanna alone would succeed him, and that her husband would be a prince consort, rather than a king.

my take on it would be heavily inspired by the biographical novel From She-Wolf to Martyr: The Reign and Disputed Reputation of Johanna I of Naples by Elizabeth Casteen

below i detail the first two episodes, purely for my own enjoyment.

EPISODE 1: A MULTITUDE OF WOLVES (1343)

“I am really alarmed about the youthfulness of the young queen, and of the new king, about the age and intent of [Sancia], about the talents and ways of the courtiers. I wish that I could be a lying prophet about these things, but I see two lambs entrusted to the care of a multitude of wolves, and I see a kingdom without a king. How can I call someone a king who is ruled by another and who is exposed to the greed of so many and (I sadly add) to the cruelty of so many?” - Francesco Petrarch, 1343

Robert ‘the Wise’, King of Naples, struggles to settle the matter of his succession. With his only son who survived to adulthood, Charles, dead, leaving behind just two daughters, he names his elder granddaughter, Johanna, heir. yet Robert’s nephew, Carobert of Hungary, insists the throne is rightfully his, and that Robert remains an usurper.

to avoid further conflict with the line of Carobert, the Angevins, Robert agrees to wed Johanna to Carobert’s second son, Andrew, while her younger sister Maria will marry Carobert’s heir, Louis.

6 year old Andrew is brought to Naples to wed the 8 year old Johanna and be reared in Robert’s court, but struggles to fit in and is frequently bullied and harassed by the Neapolitans. Johanna and he clash almost immediately, and Andrew is humiliated to find the youth of the court firmly in her favor.

nine years later, when Robert dies, Johanna is 17, and Andrew 15. the marriage remains unconsummated, and adding to the tension, neither spouse can wield any real political power until they turn 25. instead, the council is ruled by Sancia’s, Robert’s widow.

irritated by what she views as an infantilization, Johanna appeals to Pope Clement, who refuses to intervene. at the same time, Johanna’s 14 year old sister Maria is abducted and forced to marry a Neapolitan duke, Charles of Durazzo.

Andrew’s family, the Angevins, are incensed that Andrew will never be acclaimed king of Naples, even when he comes of age, and begin a rumor that Robert changed his mind on his deathbed and acclaimed Andrew as his heir instead. this only fans the flames between husband and wife, who now openly loathe one another.

EPISODE 2: ABOMINABLE AND INSIDIOUS SAVAGERY (1344-1345)

alarmed by reports of the political tensions in Naples and Johanna’s continued attempts to exert herself as queen before her 25th birthday, Pope Clement decides to intervene and insist that Andrew be acclaimed as Johanna’s co-ruler, rather than merely her consort.

Johanna steadfastly refuses, framing herself as Andrew’s guardian against an increasingly derisive and volatile court, while at the same time news of her first pregnancy is announced. yet many doubt the marriage has been consummated, and when Sancia dies in the summer of 1345, the ruling council splinters, and Johanna seizes control of Naples.

Andrew privately insists Johanna is dabbling in affairs with multiple men, but chiefly with her charismatic and cunning cousin Louis of Taranto. Johanna meets the rumors with incredulous scorn, and publicly mocks Andrew, resulting in him swearing revenge once he comes into his own inheritance. Clement begins to fear open civil war will erupt between Johanna and Andrew, and attempts to placate Andrew’s rage, to little avail.

by September of 1945, the marital discord is at a breaking point. the pregnant Johanna and Andrew travel with their respective retinues to a hunting lodge in Aversa. in the night, Andrew is lured from his bed by his own chamberlain, and viciously attacked by a group of courtiers and men at arms. beaten and strangled, his body is thrown into the gardens, where the dying Andrew is discovered by his childhood nurse.

public outrage ensues, both due to the murder and the humiliating nature of it. many hold Johanna and her cousins responsible, while Johanna’s brother in law Duke Charles decides they must give a farce of an investigation to stave off revenge from the Angevins.

the murder is largely pinned on servants and the Cabanni and Catani families, members of Johanna’s inner circle but now blood relations, including Johanna’s beloved nurse Filippa and her childhood best friend Sancia de’Cabanni, despite Johanna’s protests. Filippa, Sancia, and the other accused are tortured and burned at the stake.

Johanna gives birth to Andrew’s posthumous son, Charles, on Christmas Day, 1345, but is tormented by the memories of her toxic relationship with his father, and the infant boy’s frail health.

33 notes

·

View notes

Photo

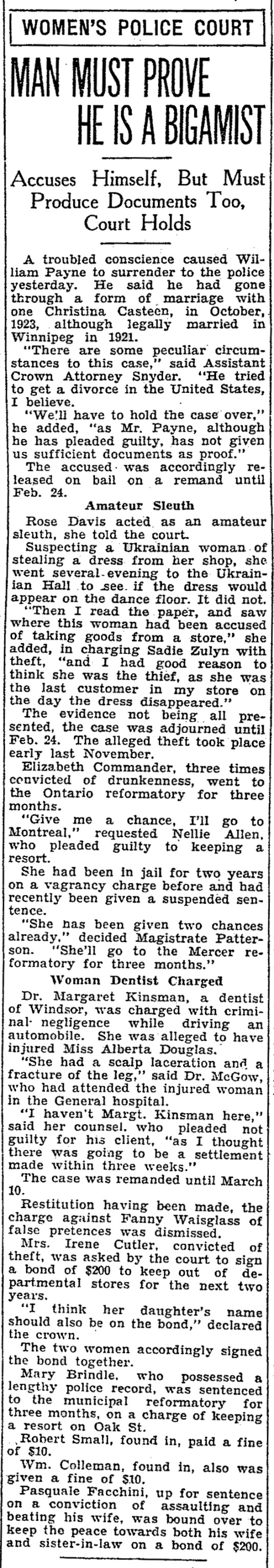

“MAN MUST PROVE HE IS A BIGAMIST,” Toronto Star. February 17, 1933. Page 2.

-----

Accuses Himself, But Must Produce Documents Too, Court Holds

----

A troubled conscience caused William Payne to surrender to the police yesterday. He said he had gone through a form of marriage with one Christina Casteen, in October, 1923, although legally married in Winnipeg in 1921.

"There are some peculiar circumstances to this case," said Assistant Crown Attorney Snyder. "He tried to get a divorce in the United States, I believe.

"We'll have to hold the case over," he added, "as Mr. Payne, although he has pleaded guilty, has not given us sufficient documents as proof."

The accused was accordingly released on bail on a remand until Feb. 24.

Amateur Sleuth

Rose Davis acted as an amateur sleuth, she told the court.

Suspecting a Ukrainian woman of stealing a dress from her shop, she went several evening to the Ukrainian Hall to see. if the dress would appear on the dance floor. It did not.

"Then I read the paper, and saw where this woman had been accused of taking goods from a store," she added, in charging Sadie Zulyn with theft, "and I had good reason to think she was the thief, as she was the last customer in my store on the day the dress disappeared."

The evidence not being all presented, the case was adjourned until Feb. 24. The alleged theft took place early last November.

Elizabeth Commander, three times convicted of drunkenness, went to the Ontario reformatory for three months.

"Give me a chance, I'll go to Montreal," requested Nellie Allen, who pleaded guilty to keeping a resort.

She had been in jail for two years on a vagrancy charge before and had recently been given a suspended sentence.

"She has been given two chances already." decided Magistrate Patterson. "She'll go to the Mercer reformatory for three months."

Woman Dentist Charged

Dr. Margaret Kinsman, a dentist of Windsor, was charged with criminal negligence while driving automobile. She was alleged to have injured Miss Alberta Douglas.

"She had a scalp laceration and a fracture of the leg," said Dr. McGow, who had attended the injured woman in the General hospital.

"I haven't Margt. Kinsman here," said her counsel. who pleaded not guilty for his client, "as I thought! there was going to be a settlement made within three weeks."

The case was remanded until March 10.

Restitution having been made, the charge against Fanny Waisglass of false pretences was dismissed.

Mrs. Irene Cutler, convicted of theft, was asked by the court to sign a bond of $200 to keep out of departmental stores for the next two years.

"I think her daughter's should also be on the bond," declared the crown.

The two women accordingly signed the bond together.

Mary Brindle. who possessed a lengthy police record, was sentenced to the municipal reformatory for three months, on a charge of keeping a resort on Oak St.

Robert Small, found in, paid a fine of $10.

Wm. Colleman, found in, also was given a fine of $10.

Pasquale Facchini, up for sentence on a conviction of assaulting and beating his wife, was bound over to keep the peace towards both his wife. and sister-in-law on a bond of $200.

#toronto#women's police court#bigamy#bigamous marriage#theft#public intoxication#assault#long criminal record#woman in the toils#women prisoners#sentenced to prison#mercer reformatory#toronto jail farm#brothel keeper#fines and costs#wife beater#great depression in canada#crime and punishment in canada#history of crime and punishment in canada

0 notes

Text

I am always 100% pro-queen, but since reading about Andrew of Hungary's murder I am honestly shook.

On the night of September 18, 1345, the power struggle between Johanna and Andrew ended in violence and death. Andrew, Johanna, their extended family, and their retinues had traveled to a royal hunting retreat in Aversa, a short distance from Naples, where they spent their time in sport and feasting while they awaited Aimery’s arrival. After Andrew had retired to bed, his chamberlain, Tommaso Mambriccio, called him from his chamber. Then the partially clothed, unarmed prince was attacked by a group of men, beaten, suffocated, and strangled with a cord. His cries went unheard by all—including, she insisted, his sleeping wife—but his absence soon alarmed his Hungarian nurse, who went to find him. Frightened by her approaching light, Andrew’s assailants threw his bruised body over the wall of the castle into the garden below, where his nurse found it and raised the alarm.

Both the royal and the papal accounts of the corpse, bloodied from desperate struggle, attest that Andrew fought violently. This much was evident from flesh found in his mouth, torn from the hand of one of his assailants. The damage to his body was extensive, revealing a degree of savagery that stunned commentators: His hair was torn out in clumps, his face lacerated, and his nostrils bloodied; his lips bore the marks of iron gauntlets and his torso those of violent pressure, while his genitals were mutilated.

(from From She-Wolf to Martyr: the Reign and Disputed Reputation of Johanna I of Naples by Elizabeth Casteen)

He was 18.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Women’s History Meme || Virtually Unknown Women (5/10)

↬ Agnès de Périgord (d. 1345)

Élie de Talleyrand was the brother of Agnes of Périgord, the mother of the three Durazzeschi princes, and was thus intimately involved in the politics and intrigues of the Neapolitan court.

— From She-Wolf to Martyr: The Reign and Disputed Reputation of Johanna I of Naples by Elizabeth Casteen

Catherine’s freewheeling lifestyle and generally conceited demeanor excited the jealousy and resentment of another cadet branch of the family— that of John, now styled duke of Durazzo as a result of the recent transaction with his sister- in-law. John had also taken a French girl, Agnes of Périgord, as a second wife after his first, a princess of Achaia, had refused to consummate the marriage and been imprisoned for her temerity. Agnes came from very good stock— not quite as grand as Catherine’s, but still very distinguished and aristocratic— and she resented her sister-in-law’s unquestioned air of superiority.

The rivalry between the two women only deepened when John died in 1336 and his lands and titles devolved upon Agnes’s eldest son, Charles of Durazzo, who was thirteen at the time of his father’s death. Agnes was devoted to Charles and very ambitious for his advancement. She knew that Catherine’s sons held a slight advantage in rank over hers, owing to their father’s having been older and therefore closer to the throne. But Agnes, while less flamboyant than Catherine, was every bit a match for the empress of Constantinople in terms of enterprise and calculation.

— The Lady Queen: The Notorious Reign of Joanna I, Queen of Naples, Jerusalem, and Sicily by Nancy Goldstone

#women's history meme#historyedit#agnes of perigord#capetian house of anjou#medieval#french history#italian history#european history#women's history#history#nanshe's graphics

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Women’s History Meme || Scandals (big or small) (4/5)

↬ The abduction of Marie of Calabria

This task became increasingly difficult, particularly after the rivalry between the Tarantini and Durazzeschi was exacerbated by the clandestine (and possibly forced) 1343 marriage of Mary of Naples (then only thirteen) to Charles of Durazzo (1323–48). Mary stood second in line to the throne; the marriage, which made Charles the husband of Naples’ possible future queen, violated the terms of Mary’s betrothal to Louis of Hungary but had tacit papal approval.

Naples became a hotbed of intrigue that threatened to erupt into open feuding. Clement VI was obliged to maintain constant contact with the Neapolitan branches of the Angevin family, with Johanna and her advisors, and with the increasingly irate Hungarians as he struggled to sustain the fragile peace within this most dysfunctional of families.

— From She-Wolf to Martyr: The Reign and Disputed Reputation of Johanna I of Naples by Elizabeth Casteen

But Agnes [of Périgord], having anticipated this response, was ready for it. Two days later, on March 28, the house of Durazzo launched the second, covert half of its plan. One of Maria’s ladies- in- waiting, a young woman by the name of Margherita di Ceccano, herself the niece of a cardinal, was an accomplice to the plot. With Margherita’s help, Charles of Durazzo quietly lured his young fiancée into the west garden of the Castel Nuovo, which abutted the grounds of his family’s estate. According to Domenico da Gravina, from there he “abducted” her to his castle, where a sympathetic priest was waiting. This priest, by the power invested in him in accordance with one of the secret bulls signed by the pope, then hurriedly and secretly married the couple.

But the performance of so unorthodox a nuptial sacrament was not enough to assure Charles of his bride. So just to make certain that there was no going back, as soon as the priest was finished, the duke of Durazzo took the precaution of consummating the marriage. Or, as Domenico da Gravina, relaying information that was obviously common knowledge at the time, reported, “having intercourse, it is said, and keeping her in his own palace.”

Even an environment as sexually permissive as court life in Naples apparently had its limits. Charles’ and Maria’s behavior scandalized the kingdom. Worse, it goaded the house of Taranto to drop its diplomatic effort in favor of a strategy centered on armed conflict.

— The Lady Queen: The Notorious Reign of Joanna I, Queen of Naples, Jerusalem, and Sicily by Nancy Goldstone

#women's history meme#maria of calabria#capetian house of anjou#italian history#medieval#french history#european history#women's history#nanshe's graphics

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

“...Both Robert and Johanna conceived of Johanna as heir not merely to Robert’s throne but also to his sovereignty. Despite having a large pool of eligible potential male successors, Robert was determined that his direct line should rule Naples. While he sought to sooth the ire of the Hungarian Angevins by marrying Johanna to Andrew, Robert had no intention of allowing them to control Naples or of allowing Andrew to rule in Johanna’s place or in her name (as many contemporaries expected). As far as Robert was concerned, Johanna’s blood legitimated her queenship, and her sex should present no obstacle. Robert’s conception of Johanna’s sovereignty proved difficult for many contemporaries to accept, and Johanna would battle public opinion that favored other heirs throughout her reign. Indeed, Johanna was as controversial as she became because she insisted on her sovereignty. She defined her role as a regnant queen as active and powerful, one that entailed divinely sanctioned rulership without the interference or participation of her consort.

…Throughout her long reign, Johanna occupied an important place in Europe’s cultural imaginary. Her reputation evolved as it did because she mattered—deeply— to her contemporaries, whether they admired or hated her. Her public image became caught up in a larger cultural conversation about women that would come to be called the querelle des femmes, or “woman question.” She was always, even for her apologists, most noteworthy as a woman and representative of the virtues, potential, weakness, or threats associated with femininity. After Andrew of Hungary’s murder, she became typed as a she-wolf—a sexualized, bloodthirsty predator—while as a papal ally she became the loving, obedient daughter of the Church. During the schism, Clementists described her as saintly and self-sacrificing, even as Urbanists denounced her as the embodiment of female irrationality and vice.

On both sides of the ecclesiastical divide, Johanna was incontrovertibly significant, a potent figure whose motivations and character were crucial to understanding the crisis facing the Church and European society. Modern scholarship has paid substantially less attention to Johanna and accorded her less importance than did her contemporaries. Scholars of Angevin Naples—a vibrant, flourishing field—conventionally treat Johanna’s reign as a decisive break, a rupture that represents the end of Angevin greatness. The definitive study of Johanna was published between 1932 and 1936 by the French scholar Émile Léonard. No English-language study of her reign has appeared in more than a century, and most surveys of the period anachronistically dismiss her as an ineffective ruler with little impact on history.

Scholarly neglect of Johanna serves as a reminder of the power of historical memory and the lingering potency of reputation: One eminent historian of southern Italy characterizes Johanna’s reign as “a constant record of court intrigues,” while a recent survey of medieval queenship speaks only fleetingly—in one sentence—of Johanna’s reign immediately after noting, “many queens-regnant ruled for short periods of time and often in moments of crisis.” Johanna’s reign was long by any standard, and for much of it, her contemporaries described her as a wise, able ruler. Yet because of her posthumous reputation, modern accounts focus on scandal and crisis, as on her supposed sexual licentiousness—perhaps explaining why, until quite recently, political history has ignored her reign. Fortunately, the tide is turning.

…Many contemporaries perceived her as a successful monarch, and her sovereignty, under the right conditions, was accepted and even celebrated. Johanna’s position as the sole regnant queen on the European stage during most of her reign, the scandals of her court, and her relationship with the papacy kept her in the public eye. Her reputation gained international dimensions, spreading via oral rumor that is largely irretrievable, but also in chronicles, prophecies, letters, poetry, and art, much of which echoes and refracts rumor. Such texts reveal not only how Johanna was perceived by her contemporaries but also how those contemporaries sought to define her and how they understood the complex of problems—queenship, femininity, royal succession—at whose nexus she stood. The commentators who helped to shape Johanna’s reputation likely did so consciously.

Reputation was of paramount—and growing—importance in medieval Europe. A person’s reputation, or fama, had crucial implications for her or his ability to take part in public life and determined her or his place in society and in what Daniel Lord Smail has called the medieval “economy of honor.” Fama was accepted as a form of proof in canon law at the turn of the twelfth century. By the thirteenth century, the great canonist Hostiensis accepted as a matter of course that criminal trials began with an inquiry into the reputation of both defendant and accuser, because public estimation was integral to identity and spoke to reliability and character. Fama had probative value and could serve as legal evidence, while infamia (infamy) was a legal status incurred by those who had committed (or were thought to have committed) a crime of which “certain public knowledge” was “so widespread as to constitute in effect the testimony of an eyewitness.”

In cases when no one came forward to lodge a formal accusation, infamia could be personified as the accuser, not only testifying against the defendant but also initiating an inquest. This was particularly common in later medieval Italian communes, which provided the social and cultural context for much of the textual consideration of Johanna’s reputation. It was understood that fama and infamia reflected communal knowledge, and even what we would now call hearsay had legal standing. In many parts of Europe, “common knowledge” was sufficient to convict a person of a crime—or at the very least to justify the use of torture to elicit a confession. The consequences of infamy were dire. Thirteenth-century French judges were empowered to imprison the defamed, who represented a danger to their communities. In both Roman and common law, infamy carried with it a range of “legal disabilities” designed to shame the infamous and bar them, and even their children, from full participation in society.

As Edward Peters argues, later medieval Europe was “a world in which status, capacity, reputation, and honor were not merely widely known and closely linked, but culturally reinforced by rigid exclusionary practices” that led to the marginalization and isolation of the infamous. For women, whose political and social activities were more proscribed than those of men, fama was of even greater significance: A woman’s reputation could condemn her if she were accused of a crime—particularly adultery or prostitution—and it had direct bearing on her social standing, her ability to marry, and the status of her children. Fama, in both the legal and cultural senses, was powerful, but it was also—late medieval commentators recognized—unstable and easily manipulated.

Given the cultural and legal importance of fama, studying reputation reveals a great deal about the people who constructed fama and the values and beliefs they held. Max Gluckman argued in a seminal 1963 article that “gossip and scandal” are “among the most important societal and cultural phenomena” for anthropological analysis. He points out that they maintain group unity and morality and help control competing factions within a community. Chris Wickham, building on Gluckman, argues that gossip is an especially important object of historical study because of what it reveals about communal values and identity. This is particularly true when it comes to discerning the cultural significance of a woman like Johanna. She lived at the center of a constantly accruing mass of gossip, which makes her reputation a particularly instructive window on later medieval culture.

Fama, as Thelma Fenster and Daniel Smail argue, is always under negotiation and shaped by multiple and competing pressures. Gossip, or “talk,” to use Fenster and Smail’s preferred term, is the medium by which “we monitor and record reputations,” and which “in medieval societies . . . did many of those things that in modern society are handled, officially, by bankers, credit bureaus, lawyers, state archives, and so on.” As the conduit for communal bias, morality, and self-policing and self-definition, fama is one of the most important indices of medieval mentalities that remains to us. As such, talk or gossip tells us a great deal about the people who feed, report, and shape it—more even than about the people who are its subject.

Medieval commentators were well aware of the power of fama, as of its usefulness and slipperiness. Chroniclers, polemicists, and writers of conduct literature touted the importance of royal reputation. The reputations of queens, in particular, were contested and subject to almost prurient attention. Queens faced “propaganda and character assassination” by political opponents, “because the question of fitness to rule and legitimacy” centered on their sexual morality, and because royal courts were places where “the politics of the personal produce a hotbed of gossip, intrigue, and suspicion.” Indeed, chronicles reveal “preoccupation with queenly sexuality” that often led to accusations of adultery and “other royal misbehavior to blame queens for past conflicts” or to discredit or delegitimize their husbands and heirs.

Fascination with the character and reputation of queens reflects the political significance and the ambiguity of queenship. For much of European history—and, indeed, for most modern historians—a queen was defined as “the king’s wife.” Most recent studies of medieval queenship, driven by feminist concerns, have striven to demonstrate queens’ agency, analyzing the power and influence many queens wielded as the wives and mothers of kings. Such studies demonstrate that queens consort and regent were able administrators, and that their cultural activities often won them great respect and admiration—even as their proximity to power and central position in the court gossip mill rendered them vulnerable to slander. Throughout Europe, the queen was “an integral part of the institution of monarchy”—something scholars have stressed in analyzing queens’ roles as intercessors, mothers, wives, and patrons, often within a well-defined familial context.

Perhaps most valuably, Theresa Earenfight has convincingly argued for the “corporate character of monarchy,” demonstrating that queens were as vital as kings to the functioning of monarchy. Johanna’s career deviates substantially from that of most medieval queens in that she ruled in her own right rather than via a husband or son. Indeed, monarchy as she practiced it could not be corporate, because Johanna could not brook competition from her consort. She stood on the cusp of a period in which women did frequently inherit thrones: She was the only regnant queen during most of her life, but the generation after her saw a woman crowned king of Poland and regnant queens in Hungary, Sicily, the united Scandinavian kingdoms, and Portugal, while her great niece, Johanna II, held the Neapolitan throne from 1414 to 1435.

She was in some sense a test case, a prominent queen whose reign witnessed the articulation of ideas about the feasibility and pitfalls of regnant queenship and paved the way for future sovereign queens like Elizabeth Tudor and Isabella of Castile. Queens were always under scrutiny, even when they played more traditional roles. Louise O. Fradenburg has argued that, in medieval literature and political thought, “the queen is a paradoxical figure because she links sovereignty to the feminine.” The power—direct and indirect, symbolic and concrete—that queens wielded made them both fascinating and troubling. They represented a disquieting incongruity, a fracture in “the structure of thought.” Johanna’s unusual position and eventful reign made her particularly fascinating, even beyond the borders of her realm.

As scholars of queenship have recognized, queens regnant “presented conceptual and legal difficulties.” They represented the tension in political thought between concerns of gender and concerns of lineage. Queens regnant challenged and were challenged by prevailing gender norms, which taught that women were intellectually, physiologically, and morally inferior to men. The prevailing understanding was that “a woman who inherited supreme authority would marry and produce a son to replace her implied submission to a husband as prescribed by Christian teaching.” Female monarchs were conceived of as placeholders upholding hereditary principle, their blood allowing them to occupy the throne only “to transmit that power to their sons.” They were “representatives of their families, agents for their fathers, husbands, and sons,” and contemporary commentators often described them in a familial context rather than portraying them as rulers in their own right.

At the same time, queens regnant, because of dynastic concerns, needed to marry and were placed at risk by marriage. As Anne J. Duggan has pointed out, “the rights of the king-by-marriage were ill-defined.” The usual expectation was that kings consort actively ruled, either in place of or alongside their wives, often generating controversy about the introduction of a foreign prince to the throne or the equally problematic elevation of “a non-dynastic male” from within the kingdom. Johanna’s many marriages were the subject of rampant gossip, both because of her refusal to allow her consorts to rule and because of the potential threat each posed to her autonomy and the interests of Naples’s ruling class. Johanna’s assertion of personal sovereignty clashed with expectations of women and wives, and it lay at the center of discussions about her, which always pondered her femininity.

Medieval antifeminism, building on classical precedent, posited that women should be subject to male authority, and that any subversion of the gender hierarchy—including within marriage—was unnatural and even dangerous. Learned opinion throughout the high and late Middle Ages barred women from positions of authority and defined them as, at best, in need of care and guidance and, at worst, an active danger to men. For Johanna’s reputation, as for descriptions of powerful women more generally, one of the key differences between men and women was that women were thought to be more lustful. In the seventh century, Isidore of Seville—whose Etymologies remained influential throughout the Middle Ages—reported that the Latin femina derived from the Greek for “fiery,” a reflection of women’s greater lust.

Theorists posited that “women’s capacity for sexual pleasure” far outstrips that of other animals (with the exception of mares) and “deviates from the ideal course of nature.” It was “an expression of irrationality and lack of control”—a form of weakness that meant women required strict oversight and that Johanna’s critics cited in their arguments against her. The arguments of medical theorists and natural philosophers dovetailed— although they never fully agreed—with theological wisdom that saw women as easily led astray and prone to temptation. Similar arguments shaped both legal and literary culture. Medieval literature of all kinds portrays women as lustful and weak. Women’s natural defects were a legal commonplace; canon law, for instance, identified women as less credible witnesses than men.

In many parts of Europe, women were denied the right to inherit immovable property, and they were excluded from most positions of political power—hence prevailing suspicion of queens. There were, however, important regional differences in inheritance patterns and aristocratic power structures. In some places, women of high birth attained positions of great wealth and power, particularly in southern France and Provence, where aristocratic women often acted as territorial lords. Elsewhere, women had less access to dynastic power. Such differences led to divergent attitudes toward female rule that helped to shape Johanna’s reputation—her rule was never as contested in Provence as it was in Naples, where women could not generally inherit immovable property and enjoyed less legal autonomy.

All of these factors contributed to widespread ambivalence to regnant queenship and to Johanna herself. They form the cultural matrix or discursive field within which her reputation took shape, and they set the terms of talk or gossip about her throughout her life. The sovereignty she asserted was provocative; the reputation she strove to create for herself, like those her contemporaries created for her, reveals the contradictions and tensions inherent in the very idea of regnant queenship, the instability of the concept of sovereignty, and the power and malleability of reputation.”

- Elizabeth Casteen, “Introduction.” in From She-Wolf to Martyr: The Reign and Disputed Reputation of Johanna I of Naples

#johanna i of naples#history#medieval#late middle ages#italian#from she-wolf to martyr#elizabeth casteen

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

“...Johanna’s date of birth is unknown, but she was likely born in 1326 or 1327, the daughter of Marie of Valois (1309–32) and Charles of Calabria (1298–1328), the son and heir of King Robert of Anjou (r. 1309–43). Charles’s death made Johanna and her sister, Mary (b. 1329), Robert’s only direct lineal heirs; Robert designated Johanna his successor in 1330. …Johanna grew up in a court noted by contemporaries for its scholarly culture—although she apparently received no formal education. Instead, she came under the tutelage of her step-grandmother, Sancia of Majorca (ca. 1285–1345), after her mother died in 1332. Sancia was famous for her piety, her devotion to the Franciscan order, and her active religious patronage, and she provided an important model for Johanna. She lived austerely even before widowhood, when she retired to a Clarissan convent, and she had more interest in contemplation and prayer than in the more worldly aspects of queenship, but she wielded great power at court and took a forceful role in the dispute about evangelical poverty.

The Angevin court was not entirely given over to piety, however. The Angevins had long patronized arts and letters, and Robert was famous for his learning. His court attracted and fostered the leading lights of fourteenth century culture, including Giotto, Petrarch, and Boccaccio. It was frequented as well by Robert’s younger brothers, Philip, prince of Taranto (1278–1331), and John of Gravina, duke of Durazzo (1294–1336), and their wives and children, including six sons whose rivalry dominated court gossip and helped shape the first two decades of Johanna’s reign. Johanna was thus the product of a court marked, on the one hand, by religious fervor and a fledgling humanist culture and, on the other, by intrigue and simmering factionalism. In 1343, Johanna succeeded Robert ahead of nine male cousins who could (and did) stake claims to her throne. She would struggle with their resentment, as with their plays for power.

From the outset, she faced criticism for the perceived iniquity of her succession, along with uncertainty about what it actually meant for her to inherit Robert’s throne. Would she truly govern? Would she incorporate her husband into her reign, or would he become the kingdom’s ruler? The conceptual and political importance of the Kingdom of Naples made such questions particularly pressing. It was the most significant European polity yet to be ruled by a woman in her own right. From their capital in Naples, the Angevins ruled the southern half of peninsular Italy, the counties of Provence and Forcalquier, and portions of the Piedmont, Albania (the duchy of Durazzo), and Greece (the Morea). Under Johanna’s forebears, the Angevin realm had approached empire; its kings exercised de facto rule over much of northern Italy while aggressively spreading their territory to the East.

Until 1282, it also included the island of Sicily; even after its loss to Aragon in the Sicilian Vespers, Angevin kings fought to reclaim the island and referred to their realm as the Kingdom of Sicily—although historians refer to the kingdom as it existed after 1282 as the Kingdom of Naples, or simply as the Regno. In addition, the Regno’s kings had claimed the symbolically potent (but territorially empty) title king of Jerusalem since 1277, when the first Angevin king, Charles I (1227–85), bought the title from Marie of Antioch. By the time of Johanna’s succession, the Regno’s rulers were as prominent as the king of France or England or the emperor himself. The competing claims of the senior branch of the Angevin family, which ruled Hungary, rendered Johanna’s succession particularly controversial.

According to the rule of primogeniture—widely accepted by the fourteenth century—Robert, the third son of Charles II (1254–1309), should not have become king. Rather, the son of his eldest brother, Charles Martel (1271–95), should have done so. However, when Charles Martel died, his young son, Charles Robert, or Carobert (1288–1342), was removed from the line of succession to protect the Regno from instability. Charles II’s second son, the future St. Louis of Toulouse (1274–97), had become a Franciscan friar and bishop and renounced his hereditary rights, so Robert succeeded Charles in Naples, while Carobert inherited the Hungarian crown. Carobert insisted that he and his sons were the Regno’s rightful rulers—a charge that his son, Louis “the Great” of Hungary (1326–82), took up in his turn.

That Robert should bequeath his kingdom to a female child when Carobert’s youth had barred him from the succession added insult to injury and was to have profound ramifications for Neapolitan history. The thorny question of the Hungarian Angevins’ rights to Naples formed the backdrop to the early years of Johanna’s reign. As a child, she was betrothed and then married to Andrew of Hungary (1328–45), the second of Carobert’s three sons, in an effort to secure peace and stability. The Hungarians saw their union as reparation for Robert’s unjust succession. Yet Johanna refused to accept Andrew as a co-ruler, and he was murdered after a protracted power struggle in 1345. The ensuing scandal, which included accusations that Johanna had first cuckolded and then murdered Andrew, would haunt her throughout her reign. It also nearly cost her kingdom: Louis of Hungary twice invaded Naples (1348–50) to avenge his brother and claim what he insisted was his birthright—an argument with which many contemporaries agreed.

Marriage, and the balance of power within marriage, posed a consistent challenge to Johanna. It had important implications for her reputation, as contemporary expectations of marriage and femininity shaped how contemporaries responded to Johanna. After Andrew’s death, she married Louis of Taranto (1320–62), another cousin with designs on her throne. Louis was the only one of Johanna’s four husbands to rule in his own name, effectively co-opting her power from 1350 to 1362 and inspiring sympathy for Johanna. Her subsequent two marriages proved less problematic for her exercise of sovereignty. Her third husband, James IV of Majorca (1336–75), was reportedly insane, and Johanna was able to enforce his secondary status and govern independently without incurring contemporaries’ ire.

Her fourth husband, Duke Otto of Brunswick-Grubenhagen (1320–98), acted as the Regno’s military leader without seeking the throne and supported Johanna loyally until her death. The latter half of Johanna’s reign differed starkly from its beginning, which was wrought with scandal, violence, and strife. Johanna emerged, over the course of the 1360s and 1370s, as a respected figure on the European political stage. She became a noted papal ally and a leader in the league that defended papal prerogatives in northern Italy. She helped to return the papacy from Avignon to Rome, and she formed friendships with the most celebrated female religious of her day, Birgitta of Sweden, Catherine of Siena, and Katherine of Vadstena. She emulated her grandparents in patronizing religious orders and foundations, and she helped to foster a vibrant artistic culture in Naples.

In the process, Johanna became known and acted as a legitimate, sovereign monarch. Ironically, her leading role in religious politics proved Johanna’s downfall after the Great Schism of the Western Church began in 1378. She was the first monarch to recognize Clement VII as pope. Her abjuration of Clement’s rival, Urban VI, led many of Johanna’s former allies to turn against her. It also resulted in her deposition and, ultimately, in her death, after Urban crowned her cousin, Charles of Durazzo—backed by her old enemy, Louis of Hungary—king in her place. Johanna died in prison, reportedly at Charles’s hand, in 1382. Childless, she had adopted the French prince Louis of Anjou as her heir; Louis and Charles waged a long war that permanently divided Johanna’s realm, plunging Angevin lands into disorder. Johanna’s reign ended even more bloodily than it had begun, leading many—particularly in Urbanist lands—to see violence and suffering as her legacy to her people.”

- Elizabeth Casteen, “Introduction. “ in From She-Wolf to Martyr: The Reign and Disputed Reputation of Johanna I of Naples

#johanna i of naples#history#late middle ages#italian#medieval#elizabeth casteen#from she-wolf to martyr

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

“When Robert of Naples named Johanna his successor, he faced the lingering question of the Hungarian Angevin claim to Naples. Johanna’s sex left her vulnerable to charges that her reign was illegitimate and reignited charges that Robert had usurped his throne from his nephew, Carobert of Hungary. With these concerns in mind, and in the interest of stability, Robert arranged a compromise with the Hungarian Angevins: Johanna’s younger sister, Mary (1329–66), would marry Louis, Carobert’s eldest son and the heir to the Hungarian throne, while Johanna would marry Andrew. In 1333, Andrew, then only five years of age, came to Naples to be educated in what was widely understood as his future kingdom. Indeed, Robert preached a sermon in honor of his arrival on Matthew 3:17, greeting the young prince with the words, “This is my beloved son, in whom I am well pleased,” thus seeming to proclaim Andrew his heir.

…Andrew was called upon to acculturate, to find a place for himself in a distinctive, fashion-conscious court. To some extent, he must have done so, but court records and reports by observers suggest that he never became a true member of court society, and instead that he remained separate from his Neapolitan cousins, including his future wife, who slighted and mocked him. Indeed, numerous chroniclers report that Andrew was subject to constant taunts and humiliation. In 1343, Robert died, and the throne passed to Johanna. She was seventeen; Andrew was only fifteen. The court at whose head they found themselves was split into multiple factions that vied to influence, control, or supplant the young couple. The most prominent divisions were between Provençal and Italian (primarily Neapolitan and Florentine) courtiers and the Hungarians who had accompanied Andrew to Naples and gradually won their own supporters.

Added to this already volatile mixture were the three Tarantini (descended from Philip of Taranto) and three Durazzeschi (descended from John of Gravina), who, as Angevin princes, had hoped to succeed ahead of Johanna or to ascend the throne through marriage to Robert’s granddaughters—something that likely sharpened their resentment of Andrew. It was in the interest of the Hungarians to garner as much power and influence for Andrew as possible and in the interest of the other factions—particularly the Tarantini and Durazzeschi—to prevent this. Robert had foreseen that factionalism might lead to chaos. Under the terms of his testament, neither Johanna nor Andrew was to come into their full inheritance before the age of twenty-five—long after the customary age of majority. Until then, they would be guided by a governing council appointed by Robert and overseen by Sancia. The council included Robert’s closest advisors, whom he trusted to guide Johanna until she was ready to rule alone.

This state of affairs was unsatisfactory to all of the factions. Johanna, for her part, balked at the unusual provision in Robert’s will that barred her from attaining her majority at eighteen. Andrew and Johanna had both already reached the age of discernment, customarily set at fourteen. Neither, therefore, was a child according to conventional definitions, and neither welcomed subjection to the governing council. Pope Clement VI (r. 1342–52) was disturbed as well by the creation of the council, which usurped his suzerain rights over Naples and his prerogative as Johanna’s legal guardian—something Johanna herself clearly recognized. Shortly after Robert’s death, she wrote to the pope, requesting that Andrew be awarded the title (though not the power) of king, most likely with the intention of ingratiating herself with the Hungarians and shortening the term of her minority. Clement refused.

In papal correspondence, Johanna was entitled regina Sicilie, a title Sancia also retained. Clement seldom addressed the governing council, which he resented, and only rarely addressed Andrew in his letters during the period immediately following Robert’s death, a clear mark of his reluctance to recognize Andrew’s claim to kingship. Papal interests were best served by maintaining firm control of Johanna and checking the ambitions of the Hungarian Angevins. Clement was thus faced with overseeing a contentious dynastic situation in a valuable papal fief. This task became increasingly difficult, particularly after the rivalry between the Tarantini and Durazzeschi was exacerbated by the clandestine (and possibly forced) 1343 marriage of Mary of Naples (then only thirteen) to Charles of Durazzo (1323–48).

Mary stood second in line to the throne; the marriage, which made Charles the husband of Naples’s possible future queen, violated the terms of Mary’s betrothal to Louis of Hungary but had tacit papal approval. Naples became a hotbed of intrigue that threatened to erupt into open feuding. Clement VI was obliged to maintain constant contact with the Neapolitan branches of the Angevin family, with Johanna and her advisors, and with the increasingly irate Hungarians as he struggled to sustain the fragile peace within this most dysfunctional of families. The Queen Regnant and Her Prince-Consort Johanna’s attempts to maintain good relations with Andrew and his family ended soon after she ascended the throne. Robert had ruled alone, refusing to share his administration with his brothers, who received the duchies of Taranto (in southern Italy) and Durazzo (in Albania) as their patrimonies.

According to Robert’s testament, Johanna was to rule as the sole inheritor of all of her grandfather’s possessions, delegating none of her power. The Hungarian Angevins might have planned to rule Naples through Andrew, but their designs were thwarted by Johanna’s refusal—supported by both the governing council and the pope—to allow him to be publicly entitled king, to swear fealty to the papacy, or even to control his own finances. Andrew was commonly referred to in person and in correspondence as “king,” but this was merely a mark of courtesy. Only the pope could confer the regal title, and Clement VI declined to do so. Johanna treated Andrew as her consort rather than as a co-ruler, thus assuming her grandfather’s position and consigning Andrew to that formerly held by Sancia.

…While Johanna’s actions and those of the governing council fulfilled Robert’s wishes, they were unusual enough to draw critical notice and at variance with what Robert’s intentions had seemed—at least to some contemporaries—prior to his death. Carobert had sent Andrew to be raised in Robert’s court with every expectation that he would eventually rule Naples. Léonard argues that Robert “had placed Andrew, as a child, on the same footing as his granddaughter; it could not have been to debase him before her for his entire life.” Yet, as Léonard also notes, Robert’s testamentary provisions incontrovertibly established just such an imbalance. Indeed, Andrew—who was entitled prince of Salerno rather than duke of Calabria, the title reserved for the heir to the throne—was denied the right to succeed to the throne even if Johanna predeceased him.

The question of Andrew’s rightful position would trouble Angevin politics long after his death. His supporters alleged that Robert had meant for Andrew to succeed him. They insisted that Robert had changed his mind about the disposition of the kingdom on his deathbed and made Andrew his heir. Such claims persisted throughout Johanna’s reign and intensified with Andrew’s murder. According to their arguments, Johanna was not the lawful heir to the throne—she ruled only through the unnatural debasement of Naples’s true sovereign, and her only claim to queenship was as Andrew’s consort. Andrew’s succession, from a certain perspective, was logical: It would have adhered to the hereditary principle favoring male candidates and mirrored the Valois succession in France.

Furthermore, it reflected the common practice by which powerful men ruled territories inherited by their brotherless wives. Andrew’s partisans, therefore, both before and after his death, could assert his threefold legitimacy as king by descent (through his grandfather), by inheritance, and as Johanna’s husband. These arguments would underpin narrative attacks on Johanna after Andrew’s death, when Andrew’s just claim to Naples’s throne became the backdrop against which the story of his murder was ultimately told. Thus, in the years between Robert’s death and Andrew’s murder, two rival arguments circulated about Andrew’s rightful position. According to the first, Andrew was Johanna’s prince-consort, not entitled and not equipped (due to his youth) to rule. According to the other, he was the legitimate king of Naples, designated by Robert as his immediate and sole successor.”

- Elizabeth Casteen, “The Murder of Andrew of Hungary and the Making of a Neapolitan She–Wolf.” in From She-Wolf to Martyr: The Reign and Disputed Reputation of Johanna I of Naples

#johanna i of naples#andrew of hungary#italian#history#elizabeth casteen#medieval#late middle ages#from she-wolf to martyr

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

“...After Louis of Taranto’s death, one of Johanna’s first concerns was necessarily dynastic. Although her children had died—Catherine, the last, sometime around 1362—she was in her mid-thirties and might still bear an heir. It was necessary, therefore, for her to marry quickly and wisely. A husband—the right husband—might provide a shield, protecting Johanna from political rivals and her reputation from the hazards of single womanhood by containing her sexuality and checking the independence that had so worried earlier commentators. At the same time, remarriage brought the dangerous ambiguities attendant on the problem of kings consort to the fore. Opening the Regno’s administration to a second Louis of Taranto was one threat, while the controversy surrounding Andrew of Hungary’s marginalization threatened to arise again as well.

…Instead, she married James IV of Majorca. The great nephew of Sancia of Majorca, James was substantially younger than Johanna and had the added attraction of being largely unconnected and politically inexperienced. Born in about 1336, James had spent much of his childhood and young adulthood imprisoned—reportedly in an iron cage—at the court of his uncle, Peter IV “the Ceremonious” of Aragon (1319–87), after his father, James III (1315–49), died attempting to regain Majorca from Peter. In May 1362, James escaped from Barcelona and fled to Naples, where he was welcomed and harbored. He seemed a suitable choice to be Johanna’s third husband, and her counselors advised her to marry him. His sad history elicited great sympathy, particularly because of his relationship to Sancia, and, given the emptiness of his royal title—which meant nothing, since Peter ruled Majorca—and his lack of resources, his marriage to Johanna presented few obvious difficulties for her exercise of sovereignty.

Their marriage contract, which denied James any Neapolitan title besides that of duke of Calabria (which made him theoretically the foremost nobleman in Naples), was finalized in December 1362, and the marriage took place early the following year. As a matter of course, he was excluded from the succession and legally defined—like Andrew and Louis before him—as Johanna’s consort. He presented little threat either to Johanna’s autonomy or to papal interests, and Urban accepted the match with equanimity. James’s role as consort was limited and minimal; he played only a scant part in the papal politics with which Urban and Johanna were concerned. Indeed, in official correspondence with the Neapolitan court, Urban excluded James, addressing Johanna as the sole ruler of Naples, while James, if addressed at all, was referred to only by his Majorcan title.

Johanna’s third marriage, despite these precautions, proved initially as tumultuous as her previous two. While she did conceive, she suffered a miscarriage in 1365 and never bore another child. James was sickly and—perhaps unsurprisingly, given his history—reportedly mentally unstable. Archbishop Pierre d’Ameil wrote to Urban during the summer of 1363 that Johanna was afraid of her husband, and both he and Johanna wrote alarmed letters to the pope about James’s behavior. He was purportedly paranoid, and his humiliation over his marginalization at court made him irrational and even violent. According to Pierre, he was willfully stubborn and prone to rages, which were particularly intense when he drank wine.

He insisted on being admitted to meetings on affairs of state and threw frightening tantrums when his will was thwarted. At times he was lucid, but periodically—according to Johanna, during certain cycles of the moon—he became maddened, and anything that might be used as a weapon had to be removed from his chamber. Johanna reported to Urban that she was forced to placate James to keep him calm in public, soothing him by allowing him into secret councils against the better judgment of her advisors. He refused, she wrote, to be content with the “honorable status” accorded him in their marriage contract.

When reminded of the legality of his position, James raged scandalously: He had frequently remarked in public, while making certain vile gestures, that, if he were able to rule, he would not renounce it either for the pope or for the Church, because he did not care to obey them. Indeed, I urged him not to say such words publicly, but he replied to the contrary that he should have revealed it openly, to which I demanded what he would dare to do. Then he hurled back that he would even pierce the body of Christ with a knife. What is certain, Sustaining Father and Lord, is that he had already made fifty pledges of donation to his familiars, some for three thousand florins, some for two thousand, some for a thousand, some for more, some for less.

When Johanna reprimanded him for pledging sums to his followers from the royal treasury to which he had no right, James became violent and slanderous: And with fury he threw himself toward me and seized me by the arm in the presence of many people, who almost believed that I would fall to the ground. And although there might then have been many exceedingly impatient to prevent actual injury to my person, I, lest due to mischief something worse occur, ordered explicitly that no one should dare to move to punish him, giving them to understand that he had done what he did not from wicked intention, but in order to comfort himself, not believing that he had dragged me so forcefully. And turning toward me, he descended into disgraceful words to defame my reputation, saying in a loud voice that I was a viricide, a vile harlot, and that I collected pimps around me who brought men to me during the night, and that he would exact an exemplary vengeance on them.

She goes on to relate that James’s erratic behavior and defamatory charges became common knowledge, causing public scandal. The Tarantini sent their wives to comfort and spend the night with her, presumably to shield her both from James and from suspicions that pimps were procuring her lovers; Mary even brought a number of armed guards. James’s crazed behavior cemented his marginal position. In deliberation with her cousins and her council, Johanna (out of necessity, she stressed to the pope) decided that she should limit contact with her husband, spending time with him alone only when her advisors deemed it safe. All of this, she insisted, depended on Urban’s approval, and she would adhere to his counsel like a good daughter (“filialiter inherebo”). There is very little doubt, given the archbishop’s corroboration, that this episode did occur, but it worked ultimately to Johanna’s benefit.

Everyone was eager to limit James’s influence. Johanna, to this end, presented herself to Urban as a loving wife who defended her husband, expressing compassionate understanding for the tribulations that had led to his insanity. As she had in her refusal to marry Philip of Touraine, she cast her assertion of independence in a pious light, presenting it not as insistence on her own will but as the only responsible course of action. James’s behavior was dangerously sacrilegious and scandalous, while hers in checking him revealed her devotion to the papacy, to the Church, and to God, whose transubstantiated flesh she charged James had threatened. Affirming the necessity of her actions, Johanna marginalized James, ruling alone and free of his interference even as she averred her love and concern for him.

Johanna thus won her independence. She was married, but without the potential pitfalls that marriage could present to regnant queens. James spent little of what remained of his life in Naples, focusing instead on regaining Majorca. His relationship with Johanna continued to be uneasy, marked by short periods of reconciliation and longer periods of estrangement. For a time, he fought with the papal league against the Visconti in northern Italy. When Peter IV “the Cruel” of Castile went to war against Aragon in 1365, James offered his services. He was captured and held for ransom at Valladolid in late 1367. Johanna, after some prodding by Urban V, helped James’s sister, the marchioness of Montferrat, to ransom him. Continuing to eschew the Neapolitan court, where Johanna reigned alone and unchallenged, James continued his military endeavors—and he was sane enough to be taken seriously by Castilian chroniclers—fighting in the Hundred Years’ War as an ally of the Black Prince until he died of a fever at Soria in January 1375.”

- Elizabeth Casteen, “A Most Loving Daughter: Filial Piety and the Apogee of Johanna’s Reign.” in From She-Wolf to Martyr: The Reign and Disputed Reputation of Johanna I of Naples

#johanna i of naples#james iv of majorca#history#italian#cw: domestic violence#from she-wolf to martyr#medieval#late middle ages#elizabeth casteen

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

“On the night of September 18, 1345, the power struggle between Johanna and Andrew ended in violence and death. Andrew, Johanna, their extended family, and their retinues had traveled to a royal hunting retreat in Aversa, a short distance from Naples, where they spent their time in sport and feasting while they awaited Aimery’s arrival. After Andrew had retired to bed, his chamberlain, Tommaso Mambriccio, called him from his chamber. Then the partially clothed, unarmed prince was attacked by a group of men, beaten, suffocated, and strangled with a cord. His cries went unheard by all—including, she insisted, his sleeping wife—but his absence soon alarmed his Hungarian nurse, who went to find him. Frightened by her approaching light, Andrew’s assailants threw his bruised body over the wall of the castle into the garden below, where his nurse found it and raised the alarm.

Both the royal and the papal accounts of the corpse, bloodied from desperate struggle, attest that Andrew fought violently. This much was evident from flesh found in his mouth, torn from the hand of one of his assailants. The damage to his body was extensive, revealing a degree of savagery that stunned commentators: His hair was torn out in clumps, his face lacerated, and his nostrils bloodied; his lips bore the marks of iron gauntlets and his torso those of violent pressure, while his genitals were mutilated. Perhaps most troubling to commentators was the indignity of Andrew’s death. Andrew was a king, even if in name only, but he had been beaten and strangled like a common criminal. The Venetian doge wrote to the count of Arbe that King Andrew was dead and had not died a good death. Petrarch bewailed the “abominable and insidious savagery” (“tam nefarias et tam truces insidias”) with which Andrew was slain and wished that “he had been killed by a sword or through some other form of manly death so that he would appear to have been killed at the hands of men, not mangled by the teeth and claws of beasts.”

In these lurid details alone, accounts of Andrew’s murder agree. Theories as to the identity of the guilty party proliferated rapidly, but no consensus was ever reached. Johanna’s supporters were widely held responsible. Reports differed as to the degree of Johanna’s collusion, if any, and which, if any, of the Angevin princes were involved. Neapolitan factionalism shaped the stories told by chroniclers, many of whom argued that the ultimate responsibility lay with Johanna and her Tarantini cousins, led by their mother, Catherine of Valois (1303–46), titular empress of Constantinople. Domenico da Gravina asserted that Johanna and her retainers arranged the hunting trip for the sole purpose of assassinating Andrew, while others, particularly propapal authors, insisted on Johanna’s complete innocence. The Hungarian faction, led by Louis of Hungary, held the entire Neapolitan royal family responsible and begged the pope to take appropriate action.

Officially, however, none of the royal family was found guilty of Andrew’s death. Instead, members of Johanna’s inner circle, including the Cabanni and Catania families, were condemned and executed for the crime. Johanna herself insisted in a letter to Siena and Florence on September 22 that an unnamed servant (Tommaso Mambriccio, who had been executed on September 20) was one of only two assailants. Charles of Durazzo, Johanna’s brother-in-law, however, responded quickly to the public outrage that engulfed Aversa and Naples, and he took the lead in discovering and prosecuting Andrew’s murderers—in part to prevent a Hungarian invasion of Naples—all the while portraying himself as Andrew’s loyal friend and supporter.

His investigation uncovered a vast conspiracy allegedly including the count of Terlizzi, Gasso de Denicy; Roberto de’ Cabanni, count of Eboli and grand seneschal of the realm, as well as Johanna’s reputed lover; Raimondo de Catania, knight and maggiordomo to the queen; Charles Artois, King Robert’s illegitimate son and count of Santa Agata and Monteodorisio, along with his son, Bertrand; Niccolò di Melizzano, Johanna’s chamberlain; Tommaso Mambriccio; and a number of other prominent members of the court. Also charged were Johanna’s nurse, Filippa Catanese—later immortalized by Boccaccio as a nefarious criminal—and her granddaughter, Johanna’s childhood companion Sancia de’ Cabanni. In the summer of 1346, Bertrand des Baux, who acted as papal delegate in the case, oversaw the punishment of the alleged masterminds. Bertrand Artois confessed under torture. Despite Johanna’s attempts to protect them, the chief conspirators were publicly tortured and burned in a series of gruesome and well-attended spectacles.

Tommaso Mambriccio, executed in the immediate aftermath of the murder, was rumored to have had his tongue removed so that he could not implicate his true accomplices. There was rampant speculation that those executed were merely scapegoats or accomplices of the real murderers, who escaped punishment. Johanna herself did not escape suspicion, despite having been exonerated by the dubious investigation and despite continuing papal support. Her subjects’ initial response after Andrew’s death was to publicly condemn her, although the prosecution and punishment of the supposed conspirators soon calmed the public outcry. Further afield, however, common report continued to condemn Johanna, and speculation about the truth surrounding Andrew’s murder was fodder for discussion long after Johanna had been formally exonerated.

Johanna’s behavior after Andrew’s murder outraged not only his family but also observers across Europe. Her letter to Florence and Siena callously seemed to hold Andrew partially responsible for his fate, which she attributed to childish imprudence that led him to walk about at night unaccompanied despite the counsel of those who had his best interests at heart. Mere weeks afterward, in the midst of open hostilities between the Angevin princes in Naples, who vied for power and sought access to the throne, Johanna requested a papal dispensation to marry her cousin, Robert of Taranto, and then, after that was denied, permission to marry Robert’s brother, Louis. Both Tarantini were widely believed to have been Johanna’s lovers before the murder, which they were thought by many to have orchestrated.

Indeed, some, including Domenico da Gravina, saw Louis’s attachment to Johanna as proof that he and his mother had schemed to murder and replace Andrew. In August 1347, Louis moved into the royal residence. When Clement VI refused to allow their marriage, Johanna and Louis married secretly on August 22. Arrangements for Johanna’s remarriage enraged Louis of Hungary and provided him additional justification to invade Naples. His vengeance was swift and brutal. During the winter of 1347, as Hungarian forces and their swelling ranks of supporters marched down the Italian peninsula, Johanna and Louis of Taranto fled separately to Avignon. Johanna was pregnant with her second child and abandoned Charles Martel, her son with Andrew (born Christmas Day, 1345), to a papal guardian. Louis of Hungary quickly captured the Regno, and he sent Charles Martel to Buda, where he died in 1348.

Louis then established himself as the ruler of Naples and continued to agitate for Johanna’s condemnation and punishment, even as he avenged himself on the rest of the royal family. Among his first victims was Charles of Durazzo, whom he executed in Aversa in January 1348. Johanna arrived in Avignon accused of murder, seemingly bereft of supporters, illicitly married to a cousin whose child she was carrying, with her kingdom overrun by a mortal enemy and her already fatherless son left motherless. To make matters worse, the Black Death reached Avignon not long after she did, leading Louis Heyligen (1304–61) to charge in a letter to Petrarch that Andrew’s assassination had caused the pestilence. Johanna’s iniquity seemed to have infected all of Europe. Perhaps if matters had stayed as bleak for Johanna as they seemed when she arrived in Avignon, her reign would have appeared less iniquitous and illegitimate to her contemporaries, even to those already disposed to be her enemies. However, Johanna’s fortunes quickly improved after her arrival in Provence.

Although she was taken prisoner by the Aixois and forced to wait three months at Châteaurenard because of Hungarian pressure on Clement VI, she reached Avignon on March 15, a day after the arrival of Louis of Taranto and his advisor, Niccolò Acciaiuoli (1310–65), who had fled Naples when it became clear that they could not defend the city. Clement almost immediately awarded the royal couple a dispensation for their marriage and appointed a commission to investigate the charges against them. Johanna appeared before the pope and Curia in consistory to defend herself against the charge that she had been complicit in Andrew’s murder. She must have had a compelling, charismatic presence; her powers of persuasion were apparently sufficient to charm the cardinals into clearing her name.

On March 30, the pope awarded Louis of Taranto the Golden Rose, the highest papal honor, customarily given to the most illustrious person at the papal court on the fourth Sunday during Lent. In early May, Clement arranged to buy Avignon—which Johanna ruled as countess of Provence—for 80,000 florins, which she would use to finance her return to Naples. Within a matter of months, the plague had driven Louis of Hungary from Italy. Johanna and Louis of Taranto returned to Naples on August 17, 1348, as its king and queen, their innocence and legitimacy tacitly affirmed by the papacy.”

- Elizabeth Casteen, “The Murder of Andrew of Hungary and the Making of a Neopolitan She-Wolf.” in From She-Wolf to Martyr: The Disreputed Reputation of Johanna of Naples

#johanna i of naples#andrew of hungary#history#medieval#late middle ages#italian#from she-wolf to martyr#elizabeth casteen

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Historians of medieval Europe must struggle with the question of how reliable their sources are, particularly when it comes to chronicles. Chroniclers were not historians in the modern sense, and their understandings of the purposes of history are distinctly at variance with modern academic sensibilities. As Gabrielle M. Spiegel has pointed out, it is the task of the historian to analyze “the social logic of the text, its location within a broader network of social and intertextual relations” and to “seek to locate texts within specific social sites that themselves disclose the political, economic, and social pressures that condition a culture’s discourse at any given moment.” In so doing, we must remember that the modern distinction between historical truth and fiction was of less concern to chroniclers than was depicting a deeper truth—one easily comprehensible to contemporary readers—that transcended the facts surrounding a given event. Paul Strohm argues that “fictionality [is] a common characteristic” of medieval chronicles and that their “fictions offer irreplaceable historical evidence in their own right.”

…The historical fictions that fourteenth-century chroniclers grafted onto the story of Andrew of Hungary’s murder must thus be read both as descriptions of specific events and circumstances and as commentaries about contemporary conditions that chroniclers as historians and storytellers were empowered to articulate. Johanna’s succession to the Neapolitan throne was in many ways an extraordinary event. She became a regnant queen as Naples was losing the support of many of the northern Italian communes, when the papacy was growing weaker as a territorial power in Italy and losing many of its traditional allies, and when laws of succession and inheritance were hardening to bar women from positions of dynastic power. Indeed, throughout most of Italy, women could not inherit immovable property of any sort, let alone large and influential kingdoms.

As Naples’s monarch, Johanna became the representative of a dynasty in which primogeniture and agnatic succession had long been favored and ahead of not one but many male relatives whose claims to her throne many of her contemporaries viewed as legitimate. In an age when Angevin kings had been seen as quasi-sacerdotal champions of the Church and Angevin blood was understood to confer holiness, the succession of a young and reportedly immoral woman to the Angevin royal title was in itself remarkable. Andrew’s murder was even more remarkable and outrageous. It was inevitable that the story of his death should have found its way into literature of all types. Yet how authors interpreted the murder and what they chose to say about it reveals far more about their reactions to the Angevin succession than about the circumstances of the murder itself.

The men who wrote about the Neapolitan regicide were clerics or, like Villani, members of an emergent merchant class with vested interest in the political affairs of Italy and the stability of their male-dominated, patrilineal society. Johanna’s queenship—which violated commonly accepted norms of inheritance and sovereignty, not to mention femininity—and the early disasters of her reign were thus frightening, threatening, and titillating by turns. Her cultural presence was powerful, and chroniclers who wrote about the early years of her reign grappled with what she represented and what her reign portended. The anxieties many felt about regnant queenship and the doubtless genuine shock and horror that Andrew’s murder inspired were joined to the political and religious concerns of those who wrote about Johanna. They had at hand a long-standing rhetorical tradition that associated women as “unredeemed flesh” with carnality and deceitfulness with which to malign her.

Indeed, their criticisms of Johanna both accused her of failing to embody tropes of feminine virtue and of being too female. It was a truism—one as effective in satire as in moral texts—in late medieval literature that, in the (ironic) words of Andreas Capellanus, Every woman in the world is . . . lustful. A woman may be eminent in distinction and rank and a man most cheap and contemptible, but if she discovers that he is sexually virile she does not refuse to sleep with him. But no man however virile could satiate a woman’s lust by any means. Boccaccio’s adulterous Neapolitan noblewoman, Fiammetta, like many of the women in his Decameron, exemplifies this tradition of oversexed literary women, and it is impossible not to see contemporary textual portrayals of Johanna as part of a larger, flourishing trope. Indeed, it was an obvious trope with which to malign her, as so many of the stock antifeminist exempla in the medieval canon revolved around libidinous or unfaithful queens, such as Guinevere and Eufeme, the treacherous queen of the thirteenth-century Roman de Silence.

In fact, queenly adultery was a cornerstone of medieval romance—as Peggy McCracken has argued, in romance, “there are only two stories to tell about the royal female body: a tale of maternity or a story of adultery.” This is not to deny that Johanna may have engaged in much of the behavior of which she was accused—we cannot know whether she did or not—but the literary preoccupation with her sexuality is telling and significant, reflective of a general “preoccupation with queenly sexuality” among medieval chroniclers, but also reflective of Johanna’s special circumstances. On the one hand, the easiest, clearest way to defame a queen was to cast aspersions on her chastity, while on the other, exposing the perceived moral failings of a woman in a position of power was one of the few mechanisms available for punishing her transgressions. The Decretum classifies adultery as one of the worst sexual sins, far more egregious than mere fornication. As such, its penalties were quite severe, particularly for women, who were treated in canon law as the offenders in adultery cases.

Most frequently, adulteresses were punished via humiliation, for instance by being paraded through city streets with their heads shaved. Accounts of Johanna’s adultery served in part to punish her by humiliating her and making her shame public. She went unpunished under law, but her textual shaming acted as what Muir has called a “literary substitute” for revenge. The attack on Johanna’s sexual morality also served, however, as a referendum both on her rule and on the concept of regnant queenship. It drew on timeworn and commonly accepted—and therefore potent and believable—tropes to defame Johanna, providing literary proof of her mala fama that was also an unrealized but legally plausible argument for her deposition. The two crimes of which she stood accused—adultery and husband murder—were intimately linked, arising from and reinforcing one another.