#he blames others but he’s the source of like 60% of camp chaos

Note

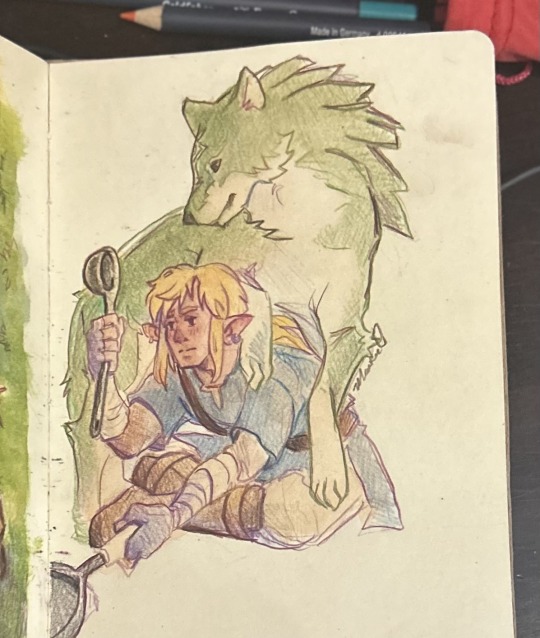

Just wanted to say, your Lu art inspires me everyday!

You’re so sweet! Thank you! I saw that you’d asked for Twilight fluff and this isn’t quite that but I hope it helps carry you through the end of the semester!

^Wild thinks maybe Wolfie has been hanging out with Time too much 🤔

#my art#artist of tumblr#tumblr artist#fanart#artist asks#nancyheart111#art#sketchbook#colored pencils#lu fanart#lu wild#lu wolfie#lu twilight#linked universe#linked universe fanart#time is a terrible influence#he blames others but he’s the source of like 60% of camp chaos#dorky pup Wolfie is my fave#wolf

556 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sound Barrier

SUMMARY: Following the end of the war both Farrier and Collins struggle to reconcile their experiences over the past six years with a world now at peace. But peace looks very different these days. Fallout from the atomic bombs is felt throughout the world and the race to prevent another drop has begun as the Iron Curtain spreads across Europe.

WARNINGS: none

Fanfiction.net Link

AO3 Link

CHAPTER 1/5

“And how are you feeling this morning?”

Suddenly light headed and disoriented. And the ringing was louder, an incessant souvenir from his time in Europe. Farrier’s mind tried to keep pace with it. Stay on rhythm. He was once good at deciphering the chaos in his head, knowing where and when to rack focus to resolve concrete forms out from their fuzzy white backdrop. Right now, it was all a blur. His mind raced but it passed nothing or maybe it passed something but that something sped away again so quickly that its pieces fragmented and blurred into the next something. His brows furrowed, and he shifted in his seat. Had they succeeded in taking his mind, the SS thugs who guarded the prison camp where he had been held. No. He would not give them the satisfaction. Violence was their only tactic. The British military, however, maybe they were the ones to blame. They had built a soldier, a fighter pilot, not a man. They had crafted a mind capable of shielding bombers from enemy fire, for directly engaging the Luftwaffe, twenty thousand kilometers above the earth, at speeds that no other human had reached and lived to talk about. They had trained him for enemy capture and torture and interrogation but never for rescue, liberation, victory. It was as if they had expected to lose or to lose him or expected this war to go on forever because they never trained him for after. But after was exactly where Farrier found himself. The world had slowed. Young women in white uniforms bustled about him, reassured him, tended to his needs. He had been pulled back from the front line. His shattered leg was useless in combat. He was returned to civilization despite knowing nothing about it. His eyes were still sharp though and they saw that civilization moved at a slower pace. His Spitfire had moved at 800km/hr. The London Underground maxed out at 60. Maybe that was the problem. Maybe his mind wasn’t broken. Maybe it was just incompatible with its new reality. His mind had been trained to keep up with his plane and the planes fighting for airspace around him. Questions from a stranger sitting across a desk were about strategy, about the strength of the British force. They were not personal. They did not concern his own well being. So how was he feeling this morning?

“Fine.” Farrier shrugged.

“Fine? Not anxious? Not excited?”

“No.”

“What about pain level? Where are you at today?”

Nurses had been posing this question to him for the past four months and Farrier still hadn’t figured out how to answer it. You were either dead, bedridden, or not. A soldier did not exist without pain. Feeling it was a good thing. It meant the limb was attached, the brain was still inside the skull. The ringing meant he could still hear. Civilians didn’t understand this. He presumed the war nurses had at one point but now that there was no war, they seemed to be the first to revert. He had learned their game. A number less than four and they would move on to their next patient. Five through seven would prompt further interrogation. Eight, nine, and ten would send a higher ranking official, maybe the doctor, and if you were lucky, more morphine. Greater than ten would earn you a smile and a flirt. He was a one on most days, an eleven when the monotony became too much. Some days he was surprised at how much damage a pretty girl with a prettier smile could repair. Other days he was surprised at how little effect their fluttery eyelashes and playful chides had. Most days though it was all just white. White uniforms, white bedding, white bandages, white walls. White noise. And ringing.

“I don’t know.”

She smiled, set down her clipboard and folded her hands on top of it. “That’s the first time you’ve answered that honestly, Mr. Farrier.”

His eyes shot to hers. He hadn’t been Mr. in fifteen years.

“That’s a sign if any,” she continued. “If you need a place to stay tonight until you can catch a train, we still have some billets available.”

“I’m just in London.”

“Oh, of course. East end, yes?”

Farrier nodded.

“That’ll be nice. Home at last.”

Again, he nodded.

She tilted her head as if waiting for more before seemingly giving up. She picked up her pen and scrawled it across the bottom of the form on her clipboard. He reached for his pack and pulled the strap over his shoulder. Then he reached for the cane leaning on the arm of his chair. He pushed himself to his feet and hobbled out of her office and out of the hospital. His steps were slow but deliberate. He hesitated only when he reached the stairs to the underground. He paused at the top and re-adjusted his pack to his back, and then to his left, and then back to his right. Its weight threw off his balance.

“Sir? Sir?”

It wasn’t until the man stepped down onto the step below him and moved to block his path that Farrier noticed him. His cheeks were still round. He was young. Too young to have fought, he reckoned, but then again that had been a frequent thought when faced with new recruits.

“Would you like a hand? I can carry your pack.”

“A soldier carries his own pack.”

“Of course, sir. I meant no offence. My brother served. Killed on D-Day. I just thought…”

The ringing grew louder, as if it was echoing out of the stairwell. The disorientation was back. Farrier blinked to clear his head but the stairs twisted further with each new frame. He clutched the hand rail and shrugged the pack from his shoulder. The boy took it and reached out a hand but quickly retracted it. Farrier smiled. He could still enact fear. He could still conjure some respect.

He nudged his damaged leg down a step and down another. The boy kept pace, always just one step ahead. He followed Farrier to the empty platform and waited beside him. The damp air hung heavy and stale around him. A few feet away a steady drip of water fell from the ceiling. Electricity buzzed along the rails, like a bombing contingent headed for the continent, hundreds of planes, Hurricanes, Halifaxes, Spitfires, flying in tight formation. Loud cracks popped from the rails every so often as the electricity jumped between them. An anti-aircraft gunner had connected and somewhere amongst the formation a plane was tumbling out of the sky. The buzz rattled on. The contingent moved forward towards the target.

A low hum came through the black tunnel where the platform ended and the tracks disappeared into the depths. Farrier turned towards the growing sound, the horizontal white tiles that lined the walls guiding his eye. He willed its approach, something to drown the ringing. The train rounded a curve in the track and light cut through the black. Enemy fire. Then the ground below him began to vibrate. The rumble traveled up his cane and into his wrist. It shook the healing bones in his shattered leg. A hit. He dropped his cane and stumbled sideways into the boy.

“Are you okay, sir?” They boy asked, breaking a more dramatic fall and helping to right him.

“’M fine. Fine. Cane,” he said.

“Right. Sorry, sir,” the boy said and hastily picked it off the concrete.

“And my pack.”

“Right.” He hesitated. “I could carry it for you. It’s really no trouble. Where are you headed?”

“Home. Where you should be.”

“It’s only four, sir.”

“No, no. I can take care of myself. Did it for the past six years, didn’t I.”

“Of course.”

Farrier took his pack and swung it back over his shoulder and limped onto the train car just before the doors slid closed. He was grateful to find a free seat before it lurched forwards. He looked out the window and saw the boy still standing there watching him. His chest tightened and sunk. He shouldn’t have snapped at him. He lifted his right hand to his brow in salute. The boy smiled and returned it and then he was gone as Farrier was pulled into the black tunnel.

------------------------------------------------------------------------

He got off six stops later and hobbled slowly up the station stairs. The sky was darkening and the streets were starting to fill with commuters on their way home. Shoes clattered impatiently on the sidewalk behind him and when there was a break in the cars, they would step into the street to rush past him. He took up too much space. He was an inconvenience. His mind raced too fast for this new world but his body moved too slow.

The streets looked different. Buildings he remembered were gone and new towers stood in their place. He wasn’t surprised. His landlord had left him a letter with the RAF offices. His flat had been hit in the Blitz. His landlord had salvaged what he could and was storing it for him. His building would not have been the only casualty. He passed a lot that was still rubble. He stopped and leaned against the lamp post that stood in front of the property. The joint in his knee was beginning to ache. He studied the twisted iron and splintered wood trying to remember what it had once been. He had once passed the building every day. Now he didn’t know if it had been shops or apartments or the doctor’s office. A grey dust coated the debris. Farrier couldn’t tell if it was from the original hit or from the rebuilding going on around it. Both, he supposed but really it didn’t matter. They were the same source. A changing world that so readily destroyed that there was no longer time to repair the broken pieces. Better to bury the mangled parts in the suffocating smoke and ash.

-------------------------------------------------------------------

“Farrier! It’s good to see you, lad. You look well. You look really well.” Farrier raised an eyebrow. With every step he took, his limp grew worse and he leaned further and further into his cane. By the time he knocked on the door his torso must have been at a forty-five-degree pitch. “Come now, lad. You were in a prison camp for four years. Some men walk out of those looking like corpses. Now come in. Sit down.” Mr. Finchley took his pack and stepped aside, ushering him into the sitting room. His reading chair was positioned opposite Mr. Finchley’s sofa by the fire place that was cracking lightly.

“I see you’ve helped yourself.”

“Waste not, want not.”

He shuffled around the coffee table and stumbled on the rug. When he sat though, he sat slowly and delicately as if half expecting the chair to give way beneath him. The legs held though and the cushions formed around his body and pulled him deeper. He let out a satisfied hum. Off his feet and reunited with a little piece of home, maybe the only piece of home that remained. The feeling was similar to when Canadian troops had stormed the prison camp or when the transport plane had touched down in Dover or when the train had pulled into Kingscross. Relief and warmth. Like he could breathe again. Tears had welled in his eyes on each occasion. They did so again. The dim room, lit only by the small orange flame, blurred before him. Mr. Finchley had disappeared to prepare a pot of tea and Farrier let cool drops pool, let them sooth his tiered eyes. He thought he was past the emotion of survival but something felt different this time. He let his head fall back against the chair. Mr. Finchley called from the kitchen and Farrier called back with his order: just black thanks. It went quiet again. Not silent but the quite of homely puttering. More peaceful than quiet really but the tinkering was something you could fall asleep to and so he let his mind drift.

The fire popped and he startled. A large ember jumped out of the hearth onto the wood floorboards. Farrier reached for his cane and pushed it back to the stone. Foot steps creaked from the hallway and he wiped the tears from his eyes. The old man entered the small room holding two cups of tea and Farrier tried to push himself upright to meet him half way.

“Sit, lad, sit.”

“You shouldn’t fuss over me.”

“A little fuss is good for a man my age. I was out everyday helping clear rubble after the bombings.”

“Should’ve known a shoddy job when I saw it,” Farrier said with a smile. “Passed at least three lots that haven’t been touched yet.”

Mr. Finchley chuckled. “Government’s not paying. What do they expect. I fixed the leaky tap of yours and then boom, Germans blow the thing to pieces. Water main shooting a mile high. Flooded the whole street. How’s that for a drip? But we managed, we managed. Would have been worse without you boys in the sky.”

Farrier gave a small nod. He wished for nothing more than to have piloted one of those planes in the skies over London. He dropped his gaze to the cup of tea in his hand. Heat poured from the porcelain over his skin. It burned. Instead of setting it down, he brought it to his lips and sipped. His tongue curled away, refusing to swallow, an act which would immerse it in the scalding liquid. His gums were left to burn.

“What do you recon now?

Forced to speak again, he swallowed. The hot liquid rushed over the roof of his mouth stripping a layer of pink skin as a crashing wave strips the sand from a beach. He shook his head. “Don’t know. I think London has moved on without me.

----------------------------------------------------------------

Farrier spent the next two nights on Mr. Finchley’s sofa. Despite it being far cushier than the hospital cot, he did not sleep. For hours, he lay in the dark, his tongue playing the piece of dead skin dangling from the roof of his mouth, pushing it back and forth, sometimes trying to tear it off completely. When exhaustion finally won, he was always jolted awake by German shouts, and German guns, and German bombs. Black swastikas pierced through the center of red maple leaves and bled outward, swallowing his saviours before swallowing him. Nights in the hospital on the other side of the city had been no different. He needed out.

He left on the third day. He limped to the train station and purchase a one-way ticket to Hemsby, a small village on the South-Eastern coast.

The train rumbled through London, through the buildings that exploded and crumbled down on him in his nightmares. Farrier closed his eyes, the hum and the gentle vibration reminded him of his Spitfire. It was the last place he had felt safe and he had set it on fire. He had stood and watched the flames burn through the chill of the early night air. The teal blue sky, suddenly black, against the bright orange and yellow. It was blinding. And then he was surrounded, guns pointed at him from all sides, commands shouted at him that he did not understand. He tried to run. He knocked a rifle out of one soldier’s hands. He knocked another soldier to the ground. The sand was deep though and his feet sank too far into it with each step. His legs felt as if they were fighting through on opposing ocean tide. A soldier caught up to him. He waited for the bullet he could see poised down the barrel of the rifle. Instead, pain shot though his right leg and he collapsed onto the sand as the soldier continued to strike him with his baton. He tried to crawl away but the soldier was relentless, even as the flames from the burning plane charged towards them. He howled as the flames engulfed him and his eyes shot open.

A nightmare. Just a nightmare.

He was quick to come down from them these days. A few deep breaths, a pan of his surroundings, each blink slow and methodical, as if he were taking a photograph, proof of reality. Across the isle, a woman read a newspaper, the front page headline: Sinews of Peace: Churchill warns of Iron Curtain. The seat across from him was empty and fabricated in dull blue and green stripes. Out the window green hills dotted with purple wild flowers rolled past. A white seagull glided across the blue sky, its wings still, stretched out wide, like those of a plane.

The salty smell of the sea washed over him as he stepped off the train. The small Hemsby platform was quiet enough he could hear the gulls call from above. The station house was just the way he remembered it from childhood visits to his grandparents: white siding, green roof, green doors, green window frames. His grandparents were long gone now though and as he limped into town, sun shown through the thin veil of his plan. Get out of London. That was what it amounted to. He remembered a hotel at the north end of the beach.

“We can have a room ready in about an hour, Sir. You can leave your bag if you want to wander through town or enjoy the beach.”

“Thanks, but I’ll stick to the pub.”

-------------------------------------------------------------------------

“You serve?” the bartender asked as he poured him a scotch.

“Something like that.”

“Hard to believe it’s over.”

Farrier hummed. He took a long sip of the amber drink placed in front of him. War talk required booze.

“I swear the airfield’s busier now than it ever was. Look, there go all the girls.”

Farrier turned in his seat. Passed the windows, a group of young women bounded, bundled in wool coats and mitts. His brow furrowed as his gaze followed the girls to the beach. Then a Spitfire shot across the horizon. It was low and its speed surprised even him. To the pub patrons, mostly middle age men, the girls seemed to be the real show. Though muffled, their enthusiastic shrieks could be heard through the glass window panes.

“What are they doing?”

“Something to do with a sound barrier, I think. I asked one of the lads once but he was well pissed at that point and I’m not the sharpest.”

Farrier’s eyes widened, and his mouth fell open, a small grin pulling across it. “They’re trying to break it,” he said. While he still had his wings, the sound barrier had been a myth of sorts. It was all theoretical, something pilots overheard engineers talking about in abstract aspirations. Maybe this would be the plane. Maybe this would be the engine. Maybe this would be the pilot. And then the war broke out and attention shifted.

“And what would that accomplish? Aside from amusing the local girls.”

Farrier shrugged. It would be the greatest achievement in aviation history, the fastest man had ever flown.

3 notes

·

View notes