#he’s just as frustrated with these former player analysts on national broadcasts as we are

Text

GRANDPA BUTCH IS TIRED OF THIS SEASON’S ANTI ISLES RHETORIC

IM LOSING IT. go off butchy!! suck on that nhl on tnt and espn+ | x x

#grandpa butch ain’t fucking around it’s playoff season bitches!!#he’s just as frustrated with these former player analysts on national broadcasts as we are#it gives me great joy#isles lb#ny islanders#butch goring

69 notes

·

View notes

Text

Now Is Not The Time to Give Up On Markelle Fultz

On Wednesday’s edition of Pardon the Interruption, NBA analyst Doris Burke offered an insightful take on the Markelle Fultz situation. Fultz, who was recently diagnosed with Neurogenic Thoracic Outlet Syndrome, has endured national ridicule for a hitch that has hampered the mechanics of his jump shot and free throw form.

Burke’s commentary is worth considering in full, and I have transcribed it below:

“You know, this is hard for me. I am the mother of a twenty-four year old son. And so the first prism through which I look at this, guys, is that of a mom. And if my son were going through this, it would be incredibly difficult to watch. We are evaluating a twenty year old in incredible scrutiny, under incredible performance pressure. It’s been over a year issue. It feels to me, personally, like if I were his mom I’d almost want him in a different organization, just to give him a fresh start. The reality is, this is a business decision for the Sixers. Brett Brown continues to be supportive. He keeps talking, saying I’m going to coach him like a son, not like the number 1 pick in the draft. I think Markelle’s inner circle has given him some interesting advice over time. I don’t know that there’s a positive outcome on either side. I’m just hopeful for the young man, that he can either (1) come back healthy in the timetable given- now 6 weeks- or (2) maybe somehow he moves to another place.”

Burke’s compassionate perspective stood out particularly because it was offered on an ESPN program. To say the network has leaned into the Fultz story would be an understatement. Earlier in the day on First Take, Stephen A. Smith had proclaimed Fultz “the biggest bust in NBA history,” and asserted in the same segment that “this man has some personal demons that are none of our business.” One month earlier, Fultz’s awkward free throw in a game against the Miami Heat was played for laughs and offered as fodder on a number of ESPN platforms, including First Take and The Jump.

ESPN is not alone among sports outlets in reveling in Fultz’s struggles; however, given the network’s venerable status and its broadcast partnership with the NBA, it is unquestionably a major amplifier. Armed with seemingly endless B-roll footage of Fultz lowlights and an impressive array of analysts, the network has considerable power in shaping the narrative around a player.

And, more than ever before, ESPN is in the storytelling business. SportsCenter long ago ceded its monopoly over the sports highlight market; in its place is a relentless brand construction and destruction machine masquerading as a highlights and analysis program.

If you’re a promising athlete, ESPN will build you an impressive pedestal on which to stand, reaping the attention and sponsorship dollars that come with it. But if you fall, the network will be the first in line to wallow in your demise like a pig in filth. Just ask Johnny Manziel.

In the end, all that matters is consumer attention. Stephen A. Smith doesn’t draw a seven-figure salary because he offers honest, measured assessments; he gets paid to speak in hyperbole and feign outrage. It’s not the take that matters. Takes are written in sand, washed away by the tide of the next news cycle. What matters is the volume of the take, and the passion with which it’s offered.

Burke’s opinion that a “fresh start” with a “different organization” would help Fultz, reasonable though it is, underestimates the ever-widening glow of the spotlight. There’s nowhere to hide anymore. It’s not like Fultz can move to Utah and play in the relative anonymity of a Western Conference city. Folks seem to enjoy watching a star fall, but there’s an even bigger market for a comeback story.

Fultz’s path to redemption, frustrating though it may be for his agent and his inner circle, is through Philadelphia. If Fultz wants out, his best bet is to opt in with the 76ers. The franchise invested two first round picks in the former Washington Husky; it’s highly likely their young guard wouldn’t net more than a 2nd round selection in any potential trade that’s made today. Fultz’s rookie contract, which pays him $8,339,880 this season and $9,745,200 in 2018-19, is a relative bargain given the NBA’s giant salary cap (currently set at $101.9 million).

Moreover, the team needs him. Watching T.J. McConnell struggle in the Raptors game only confirmed that the 76ers require a steadier hand to run the operation when Ben Simmons is on the bench. In Fultz, the organization might not have the best jump shooter at the moment. What they do have is an athletic, capable defender who can drive to the basket at will, either finishing at the rim or creating space for teammates along the perimeter.

Notwithstanding the outside noise, both parties have the luxury of time to resolve this issue. Fultz is only 20 years old; to declare him a bust not even two years into his NBA career and before he’s had an opportunity to play while healthy for an extended period is nonsensical. Thoracic outlet syndrome is eminently treatable; when Fultz has resolved his shoulder issue and is ready to repair his jump shot, there are a number of shot doctors available to him. He could look no further than Jefferson University and Herb Magee if he were so inclined. Fultz also seems to retain the support of his teammates, including Joel Embiid and Ben Simmons.

Finally, Sixers fans who have grown frustrated with Fultz need to tap once more into the deep well of patience that sustained them during the Process years. Fultz requires the same space to recover and rediscover his game that Ben Simmons and Joel Embiid were afforded.

Consider, also, adopting the more sympathetic view that Burke took in her dissection of Fultz. For my part, it’s not difficult to remember a twenty-two year old kid in disguise as an adult who was utterly failing in his first job out of college. He had convinced himself that his shortcomings were evidence of what he thought all along: that he was a failure. The same personal insecurity that had taken him to great places was now driving him into despair. The anxiety and depression that enveloped him in the ensuing years were difficult to overcome. But he ultimately discovered that this, too, would pass, and despite an extended darkness, the sun would rise again. It always does.

Unfortunately for Fultz, the former number 1 pick must work through this stretch of adversity in a spotlight under which most of us would wilt. Such is the bargain one makes when accepting a life-changing amount of money to play a sport.

Amidst the noise surrounding him, it might be difficult for Fultz to appreciate that he controls his destiny. Whether he realizes his considerable potential will be determined not by empty rhetoric issued from TV studios, but by the effort he puts into his rehabilitation and in the practice gym.

Markelle Fultz is the writer of his own story. And I’m willing to bet the best chapters are yet to come.

The post Now Is Not The Time to Give Up On Markelle Fultz appeared first on Crossing Broad.

Now Is Not The Time to Give Up On Markelle Fultz published first on https://footballhighlightseurope.tumblr.com/

0 notes

Text

How retired NBA players are helping each other survive the coronavirus

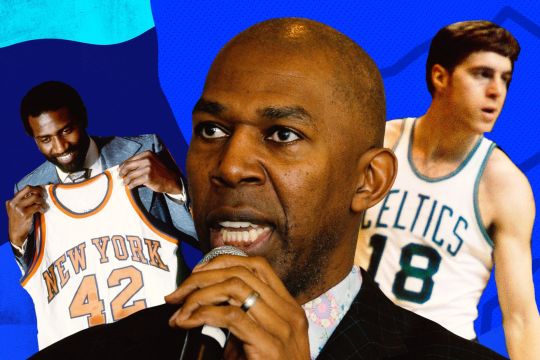

Spencer Haywood, Thurl Bailey, Dave Cowens are members of the National Basketball Retired Players Association.

Retired NBA players are more vulnerable to the coronavirus than active ones. Here’s what they’re doing about it.

Moments before the NBA suspended its season, Thurl Bailey was at Chesapeake Energy Arena preparing to call a game between the Utah Jazz and Oklahoma City Thunder that would never happen. It was a night like any other, until it wasn’t.

After Jazz all-star Rudy Gobert tested positive for coronavirus and the 18,000-plus person crowd was calmly instructed to exit the building, Bailey, who played in Utah for 10 seasons, was whisked off the court behind Jazz players and broadcast colleagues.

The 58-year-old recalls being led with about seven others into a lounge near the visitor’s locker room. There they sat, eyes glued to a television that was reporting their own surreal experience in real time. Jazz head coach Quin Snyder settled some of Bailey’s nerves when he walked in the room to brief everyone on the situation, as serious as it was. Eventually Bailey was led from that room to another, where medical professionals in protective gear, gloves, and facemasks collected his personal information so he could be tested for Covid-19.

A doctor braced him for the process by letting him know what to expect and how uncomfortable it might be, before a cotton swab was inserted into his nose and mouth. According to Bailey, it was painless and simple. Waiting for results was anything but. After they quarantined at the arena for over four hours, the Jazz spent the night in an Oklahoma City hotel. Bailey sat in his room, concern mounting as he thought about his wife and children.

“What if my test is positive?” he remembers. “Was I next to Rudy? How long was I next to him? Can you receive it if you’re on the same plane as people? All those things you start replaying in your mind.”

In the morning a Jazz employee called Bailey with good news: his results were negative. Soon after, the team flew back to Salt Lake City where they met with Angela Dunn, a state epidemiologist at Utah’s Department of Health. She went over different risk factors, explained the meaning of asymptomatic, and made strong suggestions on how they (and everyone around them) should act through the life-changing days and weeks and months that loomed ahead.

Before the season was suspended, Bailey’s daily responsibilities were not limited to his job as a broadcast analyst for the Jazz. Earlier this month, he was elected as a board of director for the National Basketball Retired Players Association (NBRPA), a 1,000-plus member organization that includes some of the sport’s most integral historic figures — former players from the NBA, WNBA, ABA, and Harlem Globetrotters.

“No one’s immune to [Covid-19], but it is a greater concern for our demographics, if you will,” Bailey says. “A lot of our players are the older generation,” Bailey said.

Right now, in the face of a crippling global pandemic, its members also represent an increasingly vulnerable and shaken segment of society that needs all the security, support, and accurate information they can find. The average member is 55 years old and over 200 of them are at least 70. All are impacted by the coronavirus, stressed over their own future, from a physical, emotional, and financial perspective.

In addition to Bailey — who previously served before he was termed out of the role due to appointment related rules — other recently elected directors include Shawn Marion, Sheryl Swoopes, and Dave Cowens. (Cowens helped found the association in 1992 with Oscar Robertson, Dave Bing, Archie Clark, and Dave DeBusschere.) Johnny Davis was named chairman of the board after spending 34 seasons as an NBA player and coach, while Jerome Williams and Grant Hill were elevated into different roles on the executive committee.

Normally, the association serves multiple functions. It’s a helping hand to members in search of new professional and/or educational opportunities. It reminds them of their own value as walking brand names, and encourages them to engage with the public in different ways. But unfortunately, our current timeline is anything but normal. The NBRPA has always expressed solicitude for its own, but right now its first, second, and third priority is to ensure the health and wellness of every member who feels susceptible.

“No one’s immune to [Covid-19], but it is a greater concern for our demographics, if you will,” Bailey says. “A lot of our players are the older generation.”

The NBRPA has been in front of the issue as best it can. All former players with at least three years service have healthcare coverage, while counseling services, scholarships, grants, and a rainy day fund for any members who are struggling to cope are in place. General awareness of these resources has been spread via email and phone calls, but this pandemic’s unpredictable scale will test mechanisms that have never been burdened by a threat this widespread and relentless.

Many members work part time and are unsure of how they’ll pay their next bill or make future house payments. Dozens have contacted the organization for assistance, which tells NBRPA President and CEO Scott Rochelle that many more may want to. “There’s probably another hundred who need to reach out or haven’t reached out but need the information,” he tells me. “So that’s guiding our efforts to date.”

Spencer Haywood, who just termed out after two straight three-year stints as the NBRPA’s chairman of the board, can’t stop thinking about his fellow members, former teammates, and friends who were suffering even before the globe was blanketed by coronavirus.

“I love them,” Haywood says. “Everybody just calls, ‘Hey can you help me with $300. I need $400, $500. I need this to make my rent. I need this to get food ... We don’t have a revenue stream. All of our guys have to work. They’re doing basketball camps. They’re traveling. They do groups. That’s how they make money ... We’re at the very beginning [of this pandemic], so I know our family, the NBA retired family, we’re gonna have some drama. I’m hoping that it’s not me. But who knows?”

Now 70 and living in Las Vegas, Haywood has done his best to stay as safe as he possibly can, stopping just short of hoarding Purell and essential groceries several weeks ago when his brother, who lives in France, first told him how deadly the virus can be. His four daughters teased him about being overly cautious, but now admit he was right to be so proactive.

Aside from his inability to resist two concerts at the House of Blues, put on by Arrested Development and Leslie Odom Jr. before everything shut down — “I couldn’t help myself!” Haywood laughs. “I went out against orders” — he’s replaced daily trips to the gym with morning yoga and five-mile walks at a nearby park.

While shuttered at home last Saturday afternoon, Haywood — a four-time NBA All-Star and ABA MVP as a 20-year-old rookie — let a few hours pass in front of ESPN’s panoramic Basketball: A Love Story documentary series, which featured his own 1971 Supreme Court case brought against the NBA that essentially allowed amateurs to bypass college and enter the NBA Draft straight out of high school. “I’m sitting there watching,” he laughs. “And I’m like ‘Damn. Pretty nice. I did some deep shit.”

As it rolled across his television, Hayward says a few friends who were also cooped up watching the same thing decided to call him: “They were like, ‘Man, I didn’t know you went through that kind of hell’. And I said ‘You were in the league!’ Man, oh man.”

But the pandemic has also emphasized a few general frustrations Haywood wants to air: “We wasted so much time in fake news and fake this, like shit, dude, if you didn’t want to be president, why did you run?”

He praises the donations made by current players to arena employees who, without NBA games, no longer have a job to do, and appreciates the players union’s unanimous vote that gave healthcare coverage to retired players back in 2016 “[NBPA President] Chris Paul has been a champion,” Haywood says. “I mean truly life saving.”

But in the midst of a broad crisis that will be felt by more former players than are currently under the NBRPA’s umbrella, Haywood also believes today’s stars should make additional contributions. “It’s a survival thing.” he says. “Think about the ones who built it for you. Who built this big conglomerate for you. I think they just don’t know. They never think about us.”

“The thing that bothers me so bad is they don’t know when it’s gonna end,” Cowens says, “Or is it?”

For the NBRPA, spring is typically a busy time of year, with college conference tournaments, the NCAA tournament, the McDonald’s All-American game, and Full Court Press, a nationwide youth clinic launched through the Jr. NBA. In the coming months, members lined up to earn between $250-500k in appearances alone. Instead, thanks to a wave of cancellations, revenue is at zero. There are still engagement opportunities being explored through NBA2K, Twitch, and social media, but the ramifications are undeniable.

Speaking appearances are another source of income for those who can leverage their name and life experience to travel across the country and meet with different people. That includes Haywood’s successor, Davis, the NBRPA’s newly elected chairman. The 64-year-old lives in Asheville, North Carolina, and normally spends his time giving talks at different colleges and universities in the area. He also sits on the foundation board at UNC-Asheville, where he’s heavily involved.

But with those opportunities no longer an option for the foreseeable future, Davis is instead staying put at his home up in the Blue Ridge mountains with his wife and son, where they’ve lived since 2009. “The warning bell has been sounded,” he tells me. “You can see the presence of what this virus has done. You can see it here in terms of how people are moving in their day to day lives. It’s different. It feels different.”

Davis is also spending some time acclimating to his new role with the NBRPA, going through the bylaws with Cowens, who lives in Maine for most of the year but has been down in Ft. Lauderdale since Jan. 10. Despite not having a full-time job, Cowens tries to keep himself busy. Last week he signed and mailed 800 basketball cards for Panini, the memorabilia company, that compensated him for the service. “It’s not a lot, but it’s enough to pay a few bills,” he says.

The Hall of Famer currently lives two blocks from the beach in a 19-story building, with 12 units on each floor. He’s neighborly, but most of the residents are on the older side, and over the past couple weeks everybody has kept to themselves.

Nights are spent out on his balcony, drinking an occasional glass of wine. When asked about the NBA deciding to suspend its season, Cowens says he would’ve liked to see at least one game played without any fans in the stands. The sound of squeaking shoes, shouting coaches, grunting players, and a natural silence that would otherwise be filled by the Jumbotron reminds him of old exhibition games that his Celtics used to play against the Knicks in upstate New York. Only 1,500 people were in the stands.

But there are more pressing matters on his mind. Now 71, Cowens is troubled by everything we don’t know about the coronavirus, how there’s no vaccine or direct word from the inflicted about how it made them actually feel. He worries about his wife. He checks up on old college buddies from Florida State, and recently phoned former Celtics teammate Don Chaney, who’s dealing with a heart condition and is likely at a higher risk than most.

“There’s so much uncertainty. If you’re feeling fine, but all of a sudden you start feeling sick, you then say ‘Am I gonna die from this?’ And so you don’t know. Young people don’t care because they’re already immune to everything in the world anyway. They’re gonna live forever. But they’re young, that’s how they think, and for the most part they’re in pretty good shape for dealing with this,” Cowens starts to chuckle. “So I don’t hang out at the clubs anymore. That’s not part of the schedule.”

No one interviewed for this story can compare such active worldwide disruption to anything they’ve witnessed or experienced firsthand. None can think of anything that comes close. It’s an unknown anxiety, like walking a plank while blindfolded from an unknown height. The future grows more murky by the day. “The thing that bothers me so bad is they don’t know when it’s gonna end,” Cowens says, “Or is it?”

He reminisces about his childhood in Newport, Kentucky. Cowens’ grandparents and aunt lived upstairs, in the same house as his parents and brother. His aunt would entertain with stories about getting to see Jim Thorpe (the only sports hero Cowens ever had) race with her own two eyes.

Cowens thinks about that time; how his grandfather lived to see his 60s despite serving in World War I and then enduring the Spanish Flu, which killed as many as 50 million people across the world. “People are going to survive,” Cowens says. That’s true. But the coronavirus will still crash into so many different lives, and so far the mortality rate for those it infects is substantially higher in seniors with underlying health issues.

Preparing for a disease that will infect and bankrupt thousands of people everyday was never in the NBRPA‘s sight line, and, frankly, it’d be a little silly if it was. Very few organizations in this country, if any, were prepared. But that hasn’t stopped them from doing whatever they can to steady the emotional wave so many are flailing through.

Right now, the organization’s primary motivation is to keep a bad situation from getting worse, and so far most retired players are doing whatever they can to limit the damage. Social distancing and self-quarantining are two examples of individual responsibility each person must take seriously. Most retired players are. The NBRPA can’t help those who won’t help themselves, but they can spread facts and manageable tactics that will save lives. The minefield of misinformation can in many ways be as dangerous as an errant cough.

Towards the end of his career, Bailey spent four seasons playing overseas. Three of them were in Italy, where he formed lifelong friendships. For the last five summers, he’s gone back to put on a basketball camp. Over the past couple weeks, Bailey has been texting with those who know firsthand what the coronavirus is capable of. They beg him to take it seriously. Given his position with the NBRPA, those around him are fortunate that he is.

“Our organization is staying on top of our members and their families to make sure they’re getting through it,” Bailey says. “It’s something that will always be etched in history. I was there. I was there the day the dominoes started to fall in Oklahoma City. In the sports world, anyway.”

0 notes