#hocart

Text

Touch | Part Three

Of bar fights and ice blocks

Words: 4.3k

Part One | Part Two | Part Four | Part Five

Warnings: slow burn to the point we might just be embers, eventual smut but next chapter I promise, teeny bit of blood, quite a lot of masculine nonsense, Joel is hot but remains grumpy

When you were in eighth grade you fell madly in love with Johnny Hocart. He was a theatre kid, wildly charismatic for a 14 year old boy, and smart enough to recognise that you had a crush on him and use you for it. You’d signed up to help out with the school play that year, Johnny being the lead in Death of a Salesman the only motivation for your sudden interest in the arts, and he turned you into his roadie almost immediately. You used your own money to fetch him chocolate from the vending machine, you carried his water bottle around behind him on the off chance he might be thirsty. The afternoon you applied his eyeliner for him, on tippy toes and terrified to topple over and take his eye out in the process, fuelled your first fumbled attempt at an orgasm (you wouldn’t get it right until eleventh grade, but you had fun figuring it out). He made you feel something heavy and relentless and heated in your chest, something that unfurled its wings and beat against your rib cage when he walked into view. The little shit let you dote on him hand and foot right up until the wrap party when he stuck his hand up Donna D’Marco’s skirt and spent the rest of the year bragging about it. You were crushed by it, the weight of the humiliation heavy on your shoulders, slumping you forward and folding you into yourself. You vowed to never forget it. But you had, until you met Joel.

Sitting in the mess hall you wondered what happened to Johnny Hocart on outbreak day. You liked the idea that he hadn’t died immediately, that he’d lived in fear for a few months before getting shot by a raider, or maybe that he’d been traded to a slaver and collapsed one day from exhaustion, from malnutrition. You hated to think of him as a clicker, because even though he was a dick no one deserved that, but at the same time you liked the kind of dramatic irony of him as a bloater, overblown as his ego had been.

You chewed your sandwich, one eye on the door, waiting for Marla and definitely not waiting for Joel. You thought instead about the clients you had booked in for the afternoon, and how you were going to finally sort out Peter Fletcher’s tennis elbow so that he could comfortably hold his rifle, and why didn’t they call it rifle elbow since that sounded so much cooler, and you considered all of this while you kept your head down, and very purposefully didn’t think about the hazel flecks in Joel’s eyes as he gazed up at you, one hand cupping and lifting his muscle while you stood square between his knees.

He’d been grumpy and dismissive, you reminded yourself, and the minute he’d felt some relief he had just up and left. You conveniently forgot the part where you had essentially ushered him out the door, suddenly keen to exorcise your living space of him. You weren’t even sure exactly what that was about, except that you had felt the first flutterings of a wing against your ribs, had recognised the feeling as something dangerous and done your best to quash it.

You were contemplating this when a shadow appeared at your table, and you startled.

‘Shit, sorry, just me,’ Ray said, and you craned your neck up to regard him. ‘Can I?’ he asked, pulling at the chair opposite you, and you nodded while you tried to calm your heart. You could see something was up.

‘You ok?’ you asked, when he was finished apologising.

‘Me and my stupid glorious brain,’ he said, and you were tempted not to let him go on any further. ‘I intercepted a message that read like it was raiders, something about a big stash, an old pharmacy that hadn’t been hit yet. Coordinates, too.’

‘That’s great,’ you said, watching his face carefully, studying the lines across his forehead, his furrowed brow, decoding Jackson’s best decoder. ‘It’s not great,’ you concluded.

‘They called in a bunch of patrols to go check it out,’ he said, and suddenly you imagined Joel on the back of a horse, leaning to the left to try and protect his right side, gun strapped to his back and his neck muscles straining under the ache of it. You grimaced. ‘Marla’s was one of them,’ Ray finished, oblivious to your sudden turmoil.

It was a poorly kept secret that Ray was in love with Marla. Poorly kept in that the only person who didn’t seem to know was her. You suspected Ray would have happily stayed put in Chicago were it not for Marla going arse over tit for the idea of living on a ranch. She had barely had to convince him to come with you both, such that he had offered to trade and borrow to get the supplies you’d need, parting with his mother’s wedding ring that he wore on a chain around his neck in the process. You weren’t even sure if Marla noticed, as it had been lost in the service of gaining three passable sleeping bags, and Marla had wrapped her arms around Ray’s neck and kissed behind his ear when he presented them to you, and you had seen in that moment that for Ray it had been enough.

You could tell Jackson hadn’t been what he expected, not least of all now having to share Marla with an entire town.

‘Ray, you did a good thing,’ you said, reaching out and putting your hand on his bicep. He nodded his head, slowly.

‘You heading to the Bison tonight?’ he asked, and you scrambled quickly to come up with an excuse.

‘I was going to check on Maria,’ you replied, grateful for your guilt reminding you that you’d still not caught up with her. ‘It’s been a while since I saw her, and she’s due soon-ish I think. I was going to take her some dinner.’

He looked at you, his mouth downturned and his brows saddled over his eyes, and you felt yourself retracting from his sadness, from his regret. Johnny Hocart had painted your face in similar colours.

‘Yeah, ok,’ you said. You tried hard not to show on your face that the idea was making your skeleton want to crawl out of your mouth and try its luck on the road. But you could see Ray was struggling, that he was bouncing his leg up and down under the table. ‘Marla’s a fighter,’ you said. He looked at you for a long moment, then nodded his head.

‘Bison. Tonight,’ he said, with finality.

You didn’t ask if he knew who else was going on the expedition. You reminded yourself you didn’t care, taking a big swig of water to drown the butterflies.

—

Propped up at a table off to the side, you had a clear view of the bar on your right and the door on your left. You were sitting with Ray and his friend that you didn’t know, and you were trying to participate in conversation but your guts were churning. As much as you wanted to stay in the moment, you couldn’t stop yourself scanning the crowd for threats. Someone smashed a glass over by the jukebox and you felt yourself startle, nearly knocking your own drink off the table. Over by the bar Chloe Bennett, owner of lumbar back problems and occasional sciatica, demonstrated how much her yelping laugh sounded like a woman being stabbed to death with her own stiletto, and you wanted very much to push your chair back and leg it, but Ray kept glancing at you to check you were ok, and his friend Simon seemed quite nice generally speaking, and if nothing else you might be able to drum up some more business out of him.

‘So you don’t charge anything?’ Simon was asking. Simon and Ray worked the radio together most days, Ray listening in to the white noise for any sign of covert communication, and Simon dutifully twisting the knobs beside him. Some part of you registered that he was conventionally attractive, and you wondered if the way he was leaning in to you as you chatted was what passed for flirting in an apocalypse, but also you were watching Ray scanning for Marla, trying to telepathically tell him it would be ok.

‘I mean, we don’t have money,’ you answered Simon.

‘You don’t barter then?’

‘I’m grateful to be here. My home is payment. My safety is payment.’

‘I don’t buy it,’ he said, and he was grinning and you knew that it was playful, but also you felt a wrinkle of frustration in the folds of your skin.

‘You don’t agree?’ Simon shrugged at you in response, and for a reason still not clear to you it made you want to slap him a little bit. You turned to Ray for help, but Ray was looking at the door, and when you looked too you saw Tommy and Joel had just walked in.

‘Fuck,’ Ray said, and you scanned his face for anxiety but found only awe. ‘They are so cool.’

Simon nodded in agreement, and you scoffed in surprise.

‘Are they?’ you asked, and your companions turned to you, confused, and Ray even slightly betrayed.

‘Tommy basically keeps this place going, him and Maria,’ Simon informed you as if this was news.

‘Peak Mama and Daddy Jackson,’ Ray chimed in.

‘Joel. He’s just…’ All three of you turned to watch him approach the bar, nodding to the bartender, who had started pouring him a whiskey the moment he walked in, and slid it over to him.

You weren’t sure how you wanted Simon to finish that sentence. Your eyes kept being drawn to Joel, the broadness of him, the salt and pepper in his hair in stark contrast to his strength, the power under his muscles and behind his eyes. You felt warm in your palms where you had held him, flexed your fingers to try and get the heat out.

You let the conversation move on without you, staring down at your drink, tracing the droplets of condensation first from the body of the glass and then down to the tabletop. If you hadn’t rushed him out would he have let you keep massaging him? Would you have peeled his shirt from his body and explored the planes of his skin? You wiped the water away before it could damage the wood.

‘They’re heading out tomorrow, first light,’ you heard Ray saying, and suddenly your attention snapped back to the present. ‘So I want to be on the radio early, before they go. See if we can find the signal again, make sure the raiders aren’t going in first.’

‘You said you thought they were further out,’ Simon pointed out. ‘That it was bouncing off the mountain.’

‘I know but we’re a day behind.’

‘That’s a lot of ground to cover.’

‘Not on horseback,’ Ray reasoned.

‘We don’t know if they have horses,’ Simon replied. He held his hands palm up on the table, in appeasement, you realised.

‘We don’t know that they don’t, either. We’re sending seven of our people out there…’ your stomach lurched at seven, and your eyes flicked again to Tommy and Joel, and you wondered if tonight was last drinks for them, not knowing if they would both make it back, a time for two brothers to come together before heading back into war. ‘…including Marla, and I just want to-‘

‘What does Marla have to do with it?’ Simon asked, and you decided then he was either an idiot or heartless, and neither option was preferable. You exhaled slowly through your teeth, and watched Ray for his reaction, and wondered if either of them would notice if you just slipped away into the crowd.

You watched Ray gather himself. ‘Marla is a good shot,’ he said, eventually.

You could feel Simon preparing to argue but suddenly there was yelling, actual yelling not imaginary traumatised-by-the-end-of-the-world yelling, and all three of you turned to the bar.

Jacob and another man you didn’t recognise were standing at the other end of the bar, pointing fingers at Joel and Tommy. Joel had already stepped around his little brother, squaring off with them, and you could see that his body was braced, a tightly wound spring in a flannel shirt and jeans. You picked your glass up off the table and cradled it to your chest, as if that would solve it.

You didn’t know Jacob. He was one of the men who had already decided he didn’t own muscles, or feel pain. You knew that he was younger than the men he was squaring off with, that he was full of bravado and empty of brains, the type to shoot first and think later, and it wasn’t lost on you that back in the day he would have made the type of cop that was the subject of several enquires and a few unflattering news items, who would have been shunted off to be the deputy of a shithole town that’s biggest crime wave was when a couple of cookbooks went missing from the local library, a town that he nevertheless tortured until he retired.

Jacob was currently yelling so hard spittle was flying across the bar, and you could make out the carotid artery along his red neck.

‘All well and good for you two,’ he was saying. ‘Sitting back while the real men go out and defend this town.’ Joel was moving forward towards him, despite Tommy pulling on his sleeve to bring him back, and everyone in the bar was now frozen, watching. Jacob continued, because he was as dumb as he was hateful. ‘Oh I’m on the fucking town council, that means I get to decide who lives and who dies without having to put my own arse on the line. Fuckin’ weak, pathetic-‘

‘Lower your voice,’ Joel said, completely calm and also utterly terrifying. Jacob laughed, actually laughed, in Joel’s face.

‘Fuck off old man,’ he spat, taking another step towards Joel, who wouldn’t back down. ‘You don’t get a say either, ridin your little brother’s dick all the way to retirement.’

‘It’s men and women,’ Joel continued, undeterred and still deathly calm. One afternoon on the road you’d come across a snake on the path, big and brown and poised with its head up, watching you. It had taken you ten minutes to back away from it, so sure it was about to lunge. Watching Joel now, inching forward towards Jacob, you had the same feeling. Jacob wasn’t following Joel, made too stupid by his misplaced entitlement, his anger and his impotent fury. ‘We are sending the real men and women to defend this town, and Tommy and I’ll be here to keep it safe while you’re gone.’

You exhaled for the first time all day, the tension you didn’t even know you were carrying with you suddenly releasing. But Jacob was more angry now, and Tommy was backing up Joel and squaring off too, and you felt the heat in the room ratchet up.

‘I’m having a baby, you fuck,’ Tommy said, and Joel raised his hand to calm him. Tommy immediately settled back behind his bigger brother.

‘Not to say we ain’t grateful,’ Joel continued, but Jacob had noticed that the whole bar was watching, that Joel was about to talk him out of an argument, that he was about to be alpha’d by a man twice his age. He took three steps forward toward Joel, who had already reached back to push Tommy out of the way, and Jacob’s arm was swinging just a fraction slower than Joel’s, who clocked the younger man hard in the jaw and sent him spinning, landing hard on the top of the bar and shattering glasses and bottles underneath him. He was only down for a second before he was back up and swinging, landing a blow on Joel’s eye socket before he and Tommy had him by the back of the collar. You realised you had stood up and had moved towards them only when you were close enough to hear Joel grunt ‘a fuckin bar fight, really? You that fuckin clichè?’

Jacob just grunted, his airway constricted by his shirt that Joel was now using as a vice, and even in the middle of the violence you could see he was careful not to compress harder than he needed to, holding him sturdy but without gripping so hard as to injure.

The four men headed for the door, Joel pushing Jacob through first and then following, using the momentum to swing the younger man out and down the stairs and into the dirt below. His friend rushed to him, pulling him up and away, and as you followed them out you heard Jacob spitting threats of his return. Joel was puffed, leant against the railing to catch his breath. He turned to his brother, checked on him, and then to you, where his eyebrows shot up and you realised he was seeing you only now. Your breath caught in your throat. You had no idea what you were doing there, either.

‘You’re hurt,’ you said after a moment, gesturing to his fist. You could see a scrape of blood pooling on the knuckle.

‘Ain’t broken,’ he said. Turning to Tommy he more or less ignored you. ‘You ok?’ he asked. Tommy nodded, before he also nodded to Joel’s fist.

‘Take him to ours,’ he said to you. ‘We got ice in the freezer. Time to work some more miracles.’

You were alarmed, pretty much constantly, but especially so when Tommy turned back to go inside.

‘You’re not coming?’ you asked, and you hated that your panic had carried through into your voice.

‘Gotta make it right here,’ he said, without turning around.

—

The walk to Maria’s was three minutes at most and still you would have flayed your own skin clean off not to have to do it. You could feel the wings now, beating hard against your rib cage, and you swallowed only to taste acid on the back of your tongue. Joel was silent, but it was the type of silence that belies being pissed off, a general curmudgeon-ing, that set you on edge.

You thought again back to your teacher. When the clients in pain, keep them talking.

‘How’s the shoulder?’ you asked, into the darkness in front of you instead of looking at Joel’s face.

‘Thought it wasn’t my shoulder,’ he said, and it took a second for you to realise he was teasing you, not goading. ‘S’ok, I hear it’s all connected,’ he pretend to console you, and you squawked out a surprised laugh, wondering if you’d ever, up until this moment, made a sound like that before.

At no point had you considered that Joel Miller could be funny. Now, though, you discovered you had even less of an idea of how to talk to him.

‘You’re not going out on the run?’ you asked, and you hoped not to sound too relieved, too hopeful.

‘Got things to look out for at home,’ he said, and you stayed quiet in the hope that he would keep talking. ‘Ellie and me, we had a rough time of it…she’s been quiet. Thought best to…’ he trailed off.

‘Maria said you went to Salt Lake?’ you asked, and because you were still unable to look at him you didn’t see him flinch. ‘Why did you have to go there?’ you continued on.

‘Didn’t realise Maria liked to gossip so much,’ he said, and you heard it then, the hardness of it.

You rushed to defend her. ‘I was just curious,’ you started, and Joel stopped you, stopped walking altogether. You turned back to him.

‘Dangerous thing,’ he said, and you wanted to tell him that you knew that, that you weren’t normally like that, that you were clever and you had survived this long because if it, but he was already turning up the path to Maria and Tommy’s place, and all you could do was trail behind him, like a fucking lap dog, worried he’d lock you out if you took too long to get inside.

From the couch Maria called for Tommy, and when Joel responded she pulled herself up to stand. You were surprised by how big she’d gotten, trying to remember the last time you’d seen a pregnant woman. Let alone a pregnant woman about to pop.

‘I know, I’m huge,’ she said, when she saw you staring and you snapped your eyes back to her face.

‘Radiant,’ you said, and she snorted.

‘Thank you for lying,’ she replied, and you felt the warmth of genuine affection between the two of you, thought for a moment of sunshine on your skin, of your sister.

‘Tommy said you had ice,’ Joel cut in, and Maria noticed Joel’s hand, her face hardening.

‘They started it,’ Joel said, and you nodded behind him to confirm that this was indeed true. You saw the suspicion in her eyes, the way she was careful with him, and you stepped forward, taking his elbow.

‘I’ll sort it,’ you said, smiling with what you hoped was confidence. Joel looked down at your hand on his arm, then up to your face, where you ignored his obvious indignation at being herded like a child. ‘On we go,’ you said, feeling like a deranged grade school teacher, trying to get her class of unruly six year olds through to 3 pm unscathed. You didn’t see the bemused look on Maria’s face as you pushed Joel down the hallway, but you wouldn’t have wanted to anyway.

Once again you found yourself crammed into a kitchen with Joel. Sitting him at the table you put some ice in a cloth then plopped down into the chair beside him and held out your hand. He stared at you, unmoving.

‘I can do this,’ he said, and you were tired then, having dealt with quite a lot of male bullshit in just the last two hours, and so you groaned and pulled his hand to you, holding him firm by the wrist lest he try and patriarchy his way out again.

‘I can do it better,’ you said simply, and he huffed out a laugh.

‘Now that I don’t deny,’ he said, and it was quiet, just barely muttered between the two of you, and when you looked up into his eyes you found that they were crinkled with something like amusement, something like affection.

You looked down, flexed his fingers for him, heard him hold his breath when you inspected the knuckle.

‘They teach you this in school, too?’ he asked, and you heard again that he was ribbing you. You decided it was a good sign.

‘No this is purely growing up with a daredevil older sister,’ you replied.

‘Family resemblance, then,’ he replied and you looked up at him sharply, angry for a second that he was calling you meek, that he was deriding you for a perfectly normal reaction to the collapse of society, but you saw nothing on his face that belied any aggression. If anything, you saw warmth.

‘This sore?’ you asked, just gently wresting a fingertip on the bone. His hands were big, with thick and powerful fingers, and you were doing your absolute best not to consider what they could do to you, if you let them.

‘S’alright,’ he murmured. For a moment you saw outside yourself, watched you hunched over inspecting the paw of a lion, a little mouse reaching in to extract a thorn.

‘Here?’ you said, hushed under the light of Maria’s kitchen. You pressed down slightly, on exactly the same spot, and heard his breath stutter. You realised the makeshift ice pack was too bulky to fit between his knuckles, so you opened it and took a block out, resolutely not looking up into his face.

‘Tell me if this is too cold,’ you said, holding the block between your fingers and running it gently over his skin.

‘Mmhmm,’ he hummed, gently. You kept the ice moving, your eyes watching his hand for any sign of a tremble, but he stayed resolute under your touch.

The heat of his skin started to melt it, cold water running down and snaking under his palm, between his fingers. It washed away the blood, so that you could see only scratches, surface abrasions, from where knuckle met jaw. You watched the pink of it, mixing with the water, little rivers of something precious, something Joel. You were aware only of your finger tips, the push of wings against your chest present but forgotten, as you witnessed him, his essence. As you gazed down on the thing that made him, that kept him, the life in his veins. As the block melted down to just a wafer, as it healed, sealed over the hurt, you lifted it to your mouth to taste it, wanting the iron and the tang of it, the sharpness of the cold mixed with the heat of him, of your open mouth.

You heard his breath hitch. Your eyes flew open, not having realised you’d closed them, and landed on his face, where you gasped when you saw the look of pure wanting, of pure desire, painted pink and red over his features. You dropped his hand in your panic, your face burning, your legs moving before your brain had even taken a moment to collect itself.

‘Thanks Maria I gotta go think Joel will be fine I hope you’re ok will drop some food around you’re the most beautiful pregnant lady I’ve ever seen take care bye’ you vomited, gathering your coat tight around your shoulders and wanting but not wanting, terrified but hoping, to hear footsteps down the hall behind you. You wrenched the door open, felt the welcome rush of cool on your face, already halfway down the porch before you heard it slam shut behind you.

You sprinted, shuffling over ice but not slowing, back to your home. As you went you followed the wall, wondering how it could have made you feel safe now that you were trapped behind it, wondering how you could possibly live with the snake poised to lunge at you, how you could outrun it when it had taken up home inside your belly, beside your breath.

Tag list (just learned what these are, lemme know if you want me to add you)

@orcasoul

#joel miller fanfic#joel miller x you#joel miller x reader#pedro pascal fanfiction#the last of us fanfiction#fanfic#joel miller#pedro pascal#the last of us#tlou

67 notes

·

View notes

Text

known how to rescue the people they were studying from the barbarism

of pre-logic except by identifying them with the most prestigious of their

colleagues - logicians or philosophers (I am thinking of the famous title,

'The primitive as philosopher'). As Hocart (1970, 32) puts it, 'Long ago

[man] ceased merely to live and started to think how he lived; he ceased

merely to feel life : he conceived it. Out of all the phenomena contributing

to life he formed a concept of life, fertility, prosperity, and vitality. ' Claude

Levi-Strauss does just the same when he confers on myth the task of

resolving logical problems, of expressing, mediating and masking social

contradictions - mainly in some earlier analyses, such 'La geste d' Asdiwal'

(1958) - or when he makes it one of the sites where, like Reason in history

according to Hegel, the universal Mind thinks itself, 7 thereby offering for

observation 'the universal laws which govern the unconscious activities of

the mind' (1951).

The indeterminacy surrounding the relationship between the observer's

viewpoint and that of the agents is reflected in the indeterminacy of the

relationship between the constructs (diagrams or discourses) that the

observer produces to account for practices, and these practices themselves.

This uncertainty is intensified by the interferences of the native discourse

aimed at expressing or regulating practice - customary rules, official

theories, sayings, proverbs, etc. - and by the effects of the mode of thought

that is expressed in it. Simply by leaving untouched the question of the

principle of production of the regularities that he records and giving free

rein to the 'mythopoeic' power of language, which, as Wittgenstein pointed

out, constantly slips from the substantive to the substance, objectivist

discourse tends to constitute the model constructed to account for practices

as a power really capable of determining them. Reifying abstractions (in

sentences like 'culture determines the age of weaning'), it treats its

. ' 1 " " ' 1 1 " d f d constructions - cu ture , structures , socia c asses or mo es 0 pro uc-

tion' - as realities endowed with a social efficacy. Alternatively, giving

concepts the power to act in history as the words that designate them act

in the sentences of historical narrative, it personifies collectives and makes

them subjects responsible for historical actions (in sentences like 'the

bourgeoisie thinks that . . . ' or 'the working class refuses to accept

. . . ') . 8 And, when the question cannot be avoided, it preserves appearances

by resorting to systematically ambiguous notions, as linguists say of

sentences whose representative content varies

#pierre bordeu#marxist leninist#communism#marxism#marxist- leninist#marxism-leninism#french#french theory

0 notes

Photo

{🔥| Michael Langdon/Cody Fern Art - Sojourn |🔥} - - - - - - - - - - - #Codyfern #codyfernart #duncanshepherd #houseofcards #hoc #hocart #duncanshepherdart #facetscape #facetscapeart #copic #copicmarkers #copicart #markerart #traditionalart #michaeangdon #michaellangdonart #americanhorrorstory #ahsapocalypse #ahs8 #apocalypse #ahs #ahsart #art #digitalart https://www.instagram.com/p/BsvUgfvDPGD/?utm_source=ig_tumblr_share&igshid=1562u02v7weke

#codyfern#codyfernart#duncanshepherd#houseofcards#hoc#hocart#duncanshepherdart#facetscape#facetscapeart#copic#copicmarkers#copicart#markerart#traditionalart#michaeangdon#michaellangdonart#americanhorrorstory#ahsapocalypse#ahs8#apocalypse#ahs#ahsart#art#digitalart

0 notes

Photo

Giffard Hocart Lenfestey (1872 - 1943) - Evening, the Stream. Oil on canvas.

32 notes

·

View notes

Photo

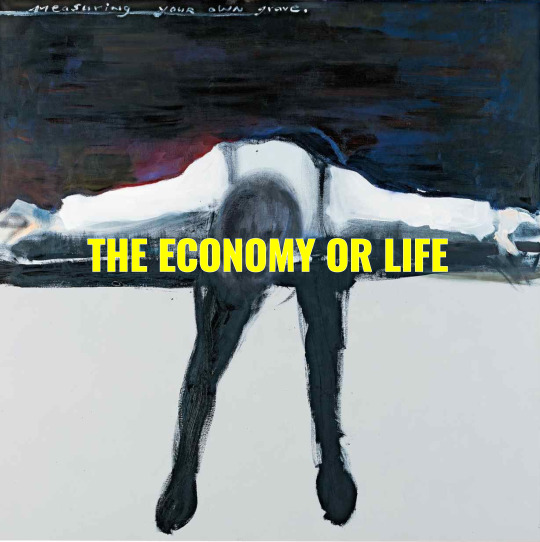

The Economy or Life

First published in Lundimatin #236, March 30th, 2020.

Cannot you see, cannot all you lecturers see, that it is we that are dying, and that down here the only thing that really lives in the Machine? We created the Machine, to do our will, but we cannot make it do our will now. It has robbed us of the sense of space and of the sense of touch, it has blurred every human relation and narrowed down love to a carnal act, it has paralyses our bodies and our wills, and now it compels us to worship it.

—E. M. Forster, "The Machine Stops" (1909)

Not every official transmission is fake news. Amidst so many disconcerting lies, today's rulers appear genuinely heartbroken when detailing the extent to which the economy is suffering. As for the elderly left to choke at home alone so they don't cause a spike in official statistics, or clog up our hospitals...of course, a thought for them too. But that a good corporation might die: this really forms a lump in their throats. Just look at them rushing to its bedside. It's true, people everywhere are dying from respiratory failure -- but the market must not be deprived of oxygen. The economy will never be short on the artificial ventilators it needs; the central banks will see to that. Our rulers are akin to an aging heiress who sees a man bleeding out in her living room and frets over the stains on her carpet. Or like that expert of national technocracy who remarked in the recent report on nuclear safety that, "the true victim of any nuclear disaster would be the economy."

Faced with the present microbial storm, one that we were warned of by every wing of government since the late 1990s, we are awash in conjecture about our leaders’ lack of preparation. How could it be that masks, hairnets, beds, caretakers, tests, and remedies are in such short supply? Why all these last-minute measures, all these sudden reversals of doctrine? Why all these contradictory injunctions -- confine yourself but go to work, close the shops but not the large retail outlets, stop the circulation of the virus but not the goods that carry it? Why all these grotesque impediments to mass testing, to drugs that are so obviously effective and inexpensive? Why the choice of general containment rather than detection of sick subjects? The answer is simple and ever the same: it's the economy, stupid!

Rarely has the economy appeared so clearly for what it truly is: a religion, if not a cult. A religion is, after all, no more than a sect that has taken power. Rarely have our rulers appeared so obviously possessed. Their mad cries for sacrifice, for war, for total mobilization against an invisible enemy, their calls for unity among the faithful, their incontinent verbal deliriums no longer embarrassed in the slightest by overt paradox—it’s the same as any evangelical celebration. And we are summoned to endure every single sermon from behind our glowing screens, with mounting incredulity. The defining characteristic of this brand of faith is that no fact is capable of invalidating it. Far from standing condemned by the spread of the virus, the global reign of the economy has made use of the opportunity to reinforce its presuppositions.

The new ethos of confinement, wherein "men derive no pleasure (but on the contrary great displeasure) from being in the company of one another", wherein everyone appears to us in our strict separation as a potential threat to our life, wherein the fear of death imposes itself as the foundation of the social contract, only fulfills the anthropological and existential hypothesis of Hobbes' Leviathan — Hobbes, whom Marx reputed to be "one of the oldest economists in England, and among the most original philosophers". To situate this hypothesis, it’s worth recalling that Hobbes was entertained by the fact that his mother gave birth to him while terrified by lightning. Born of fear, he logically saw in life only the fear of death. "That's his problem," we’re tempted to say. No one is obliged to make such a sick worldview the basis of their existence, let alone of all existence. And yet here we are. The economy, whether liberal or Marxist, left or right, planned or deregulated, is the very illness now being prescribed for general health. In this, it is indeed a religion.

As our friend Hocart remarked, there is no fundamental difference between the president of a "modern" nation, a tribal chief in the Pacific Islands, or a pontiff in Rome. Their task is always to perform the propitiatory rites that will bring prosperity to the community, that reconcile it with the gods and preserve it from their wrath, that ensure unity, and prevent the people from scattering. "His raison d'être is not coordination but to preside over the ritual" (A-M Hocart, Kings and Courtiers): the root of our leaders' incurable imbecility lies in their failure to understand this principle. It is one thing to attract prosperity, and another to manage the economy. It is one thing to perform rituals, and another to govern people's lives. How much of power’s nature is purely liturgical is amply demonstrated by the profound uselessness, indeed the essentially counter-productive activity of our current rulers, who view the situation only as an unprecedented opportunity to excessively expand their own prerogatives, and to ensure no one tries to take their miserable seats. In view of the calamities befalling us, the leaders of today’s economic religion really are truly the last of the deadbeats when it comes to propitiatory rites. Their religion is in fact nothing but infernal damnation.

And so we stand at a crossroads: either we save the economy, or we save ourselves. Either we exit the economy, or we allow ourselves to be drafted into the great "army in the shadows” of those to be sacrificed in advance. The whole 1914-1918 rhetoric of the moment leaves no room for doubt: it's the economy or life. And since it’s a religion we’re dealing with, what we're facing now is a schism. The states of emergency decreed everywhere, the expansions of police power, the population control measures already enacted, the lifting of all limits to exploitation, the sovereign decision on who lives and who dies, the unflinching praise of Chinese governmentality—such means are not designed to provide for the "salvation of the people" here and now, but to prepare the ground for a bloody "return to normal", or else the establishment of a normality even more anomic than that which prevailed before. In this sense, the leaders are for once telling the truth: the afterwards [l’après] is indeed being played out now. It is now that doctors, nurses, and caretakers must abandon any loyalty to those attempting to flatter them into self-sacrifice. It is now that we must wrest control of our health and wellness from the disease industry and "public health" experts. It is now that we must set up mutual-aid networks of autonomous supply and production, if we are avoid succumbing to the blackmail of dependency that aims to redouble our subservience. It is now, in the extraordinary suspension we are living through, that we must figure out everything we will need in order to live beyond the economy, and all that will be required in order to prevent its return. It is now that we must nourish the complicities that can limit the impudent revenge of a police force that knows it is hated. It is now that we need to de-confine ourselves---not out of mere bravado, but gradually, with all the intelligence and attention that befits friendship. It is now that we must elucidate the life we want: what this life requires us to build and to destroy, with whom we want to live, and whom we no longer wish to live with. No care should be given to those leaders currently arming themselves for war against us. No "living together" with those who would leave us for dead. We will trade no protection at the price of submission; the social contract is dead, it is up to us to invent something else. The rulers of today know well that on the day of de-confinement we will have no other desire than to see their heads roll, and that is why they will do everything they can to prevent that day from coming, to diffract, control, and delay our exit from confinement. It is up to us to decide when, and on what terms it happens. It is up to us to give form to the afterwards. It is up to us to sketch technically feasible and humane routes out of the economy. "We’re standing up and walking out" said a deserter from Goncourt not so long ago. Or, to quote an economist attempting to detox from his own religion: "I see us free, therefore, to return to some of the most sure and certain principles of religion and traditional virtue: that avarice is a vice, that the exaction of usury is a misdemeanor and the love of money is detestable, that those walk most truly in the paths of virtue and sane wisdom who take least thought for the morrow. We shall once more value ends above means and prefer the good to the useful. We shall honor those who can teach us how to pluck the hour and the day virtuously and well, the delightful people who are capable of taking direct enjoyment in things, the lilies of the field who toil not, neither do they spin.”

Translated by Ill Will Editions

58 notes

·

View notes

Link

Sometime before Hocart was asking, “Why not call them gods?” Andrew Lang in effect asked of gods, “Why call them spirits?” Just because we have been taught our god is a spirit, he argued, that is no reason to believe “the earliest men” thought of their gods that way ([1898] 1968: 202). Of course, I cannot speak here of “the earliest men”—all those suggestive allusions to the state of nature notwithstanding—but only of some modern peoples off the beaten track of state systems and their religions. For the Inuit, the Chewong, and similar others, Lang would have a point: our native distinction between spirits and human beings, together with the corollary oppositions between natural and supernatural and spiritual and material, for these peoples do not apply. Neither, then, do they radically differentiate an “other world” from this one. Interacting with other souls in “a spiritual world consisting of a number of personal forces,” as J. G. Oosten observed, “the Inuit themselves are spiritual beings” (1976: 29). Fair enough, although given the personal character of those forces, it is more logical to call spirits “people” than to call people “spirits.” But in either case, and notwithstanding our own received distinctions, at ethnographic issue here is the straightforward equivalence, spirits = people.

The recent theoretical interest in the animist concepts of indigenous peoples of lowland South America, northern North America, Siberia, and Southeast Asia has provided broad documentation of this monist ontology of a personalized universe. Kaj Århem offers a succinct summary:

As opposed to naturalism, which assumes a foundational dichotomy between objective nature and subjective culture, animism posits an intersubjective and personalized universe in which the Cartesian split between person and thing is dissolved and rendered spurious. In the animist cosmos, animals and plants, beings and things may all appear as intentional subjects and persons, capable of will, intention, and agency. The primacy of physical causation is replaced by intentional causation and social agency. (2016: 3)

It only needs be added that given the constraints of this “animist cosmos” on the human population, the effect is a certain “cosmo-politics” in Eduardo Viveiros de Castro’s sense of the term (2015). Indeed, the politics at issue here involves much more than animist inua, for it equally characterizes people’s relations to gods, disembodied souls of the dead, lineage ancestors, species-masters, demons, and other such intentional subjects: a large array of metapersons setting the terms and conditions of human existence. Taken in its unity, hierarchy, and totality, this is a cosmic polity. As Déborah Danowski and Viveiros de Castro (2017: 68–9) very recently put the matter (just as this article was going to press):

What we would call “natural world,” or “world” for short, is for Amazonian peoples a multiplicity of intricately connected multiplicities. Animals and other spirits are conceived as so many kinds of “‘people” or “societies,” that is, as political entities. … Amerindians think that there are many more societies (and therefore, also humans) between heaven and earth than are dreamt of in our philosophy and anthropology. What we call “environment” is for them a society of societies, an international arena, a cosmopoliteia. There is, therefore, no absolute difference in status between society and environment, as if the first were the “subject” and the second the “object.” Every object is another subject and is more than one.

This is a wonderful article. bolding mine

19 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Taken from the book Escape from Evil. Ernest Becker explores the the foundation of rituals using Hocart’s work to highlight the balance we need in order to feel comfortable in our place between the earth and the sky. “Happiness can exist only in acceptance.” - George Orwell. We need to understand our nature and accept who and what we are. “For after all, the best thing one can do when it’s raining is let it rain.” - Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. #acceptance #ritual #rituals #life #lifequotes #live #living #beherenow #beyourself #beyou #be #motivation #motivationalquotes #happiness #happinessquotes #quotes #quotestoliveby #quotesaboutlife #quotestagram #ernestbecker https://www.instagram.com/p/CTodI1bFofs/?utm_medium=tumblr

#acceptance#ritual#rituals#life#lifequotes#live#living#beherenow#beyourself#beyou#be#motivation#motivationalquotes#happiness#happinessquotes#quotes#quotestoliveby#quotesaboutlife#quotestagram#ernestbecker

0 notes

Photo

Solemn Stillness

Giffard Hocart Lenfestey

Wolverhampton Art Gallery

111 notes

·

View notes

Text

the white man truly is post-logical

0 notes