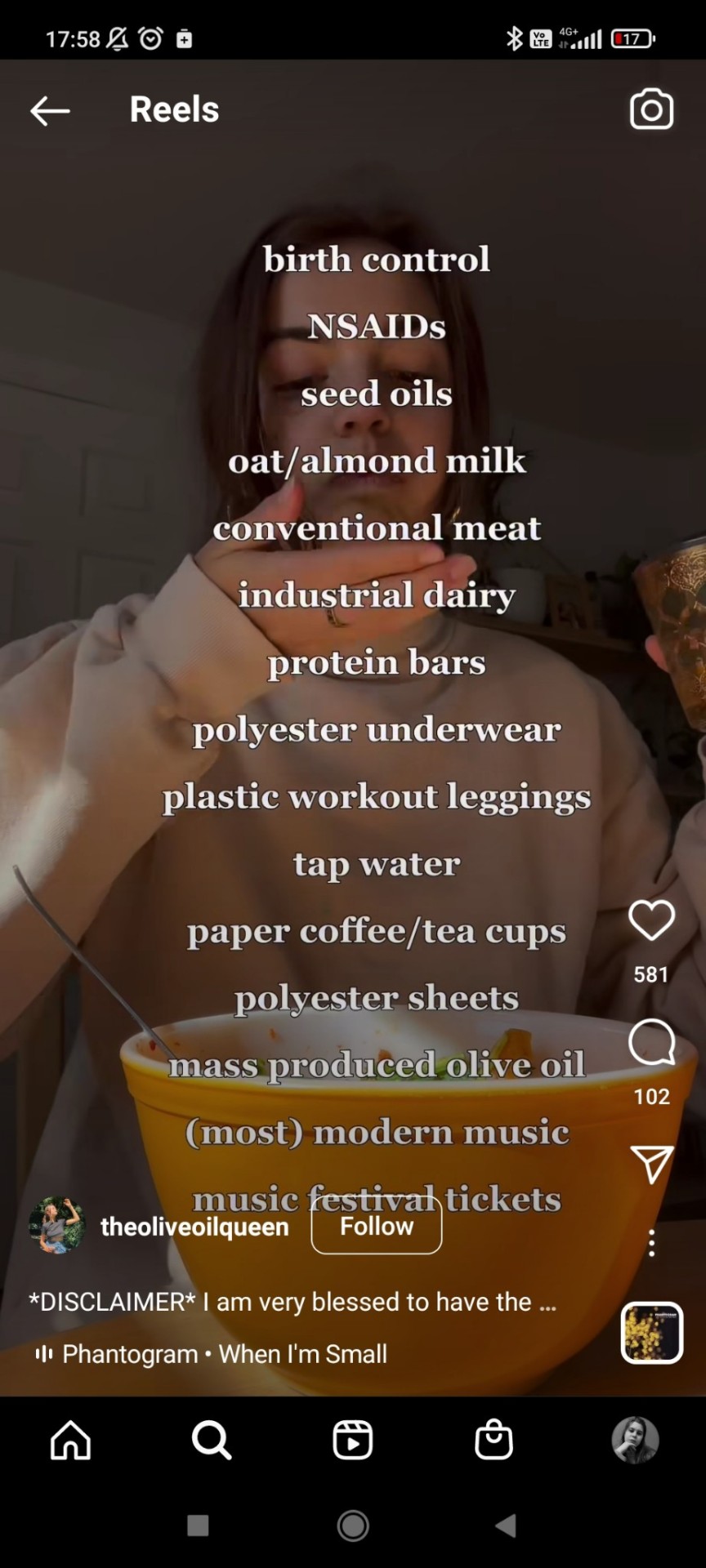

#i agree with the polyester underwear and sheets but

Text

girl what

#i agree with the polyester underwear and sheets but#but music?????#tap water???#seed oils????#im 🤨🤨🤨

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The ancient fabric that no one knows how to make

In late 18th-Century Europe, a new fashion led to an international scandal. In fact, an entire social class was accused of appearing in public naked.

The culprit was Dhaka muslin, a precious fabric imported from the city of the same name in what is now Bangladesh, then in Bengal. It was not like the muslin of today. Made via an elaborate, 16-step process with a rare cotton that only grew along the banks of the holy Meghna river, the cloth was considered one of the great treasures of the age. It had a truly global patronage, stretching back thousands of years – deemed worthy of clothing statues of goddesses in ancient Greece, countless emperors from distant lands, and generations of local Mughal royalty.

There were many different types, but the finest were honoured with evocative names conjured up by imperial poets, such as "baft-hawa", literally "woven air". These high-end muslins were said to be as light and soft as the wind. According to one traveller, they were so fluid you could pull a bolt – a length of 300ft, or 91m – through the centre of a ring. Another wrote that you could fit a piece of 60ft, or 18m, into a pocket snuff box.

Dhaka muslin was also more than a little transparent.

While traditionally, these premium fabrics were used to make saris and jamas – tunic-like garments worn by men – in the UK they transformed the style of the aristocracy, extinguishing the highly structured dresses of the Georgian era. Five-foot horizontal waistlines that could barely fit through doorways were out, and delicate, straight-up-and-down "chemise gowns" were in. Not only were these endowed with a racy gauzy quality, they were in the style of what was previously considered underwear.

In one popular satirical print by Isaac Cruikshank, a clique of women appear together in long, brightly coloured muslin dresses, through which you can clearly see their bottoms, nipples and pubic hair. Underneath reads the description, "Parisian Ladies in their Winter Dress for 1800".

Meanwhile in an equally misogynistic comedic excerpt from an English women's monthly magazine, a tailor helps a female client to achieve the latest fashion. "Madame, ’tis done in a moment," he assures her, then instructs her to remove her petticoat, then her pockets, then her corset and finally her sleeves… "‘Tis an easy matter, you see," he explains. "To be dressed in the fashion, you have only to undress."

Still, Dhaka muslin was a hit – with those who could afford it. It was the most expensive fabric of the era, with a retinue of dedicated fans that included the French queen Marie Antoinette, the French empress Joséphine Bonaparte and Jane Austen. But as quickly as this wonder-cloth struck Enlightenment Europe, it vanished.

By the early 20th Century, Dhaka muslin had disappeared from every corner of the globe, with the only surviving examples stashed safely in valuable private collections and museums. The convoluted technique for making it was forgotten, and the only type of cotton that could be used, Gossypium arboreum var. neglecta – locally known as Phuti karpas – abruptly went extinct. How did this happen? And could it be reversed?

A fickle fibre

Dhaka muslin began with plants grown along the banks of the Meghna river, one of three which form the immense Ganges Delta – the largest in the world. Every spring, their maple-like leaves pushed up through the grey, silty soil, and made their journey towards straggly adulthood. Once fully grown, they produced a single daffodil-yellow flower twice a year, which gave way to a snowy floret of cotton fibres.

These were no ordinary fibres. Unlike the long, slender strands produced by its Central American cousin Gossypium hirsutum, which makes up 90% of the world’s cotton today, Phuti karpas produced threads that are stumpy and easily frayed. This might sound like a flaw, but it depends what you’re planning to do with them.

Indeed, the short fibres of the vanished shrub were useless for making cheap cotton cloth using industrial machinery. They were fickle to work with, and they’d snap easily if you tried to twist them into yarn this way. Instead, the local people tamed the rogue threads with a series of ingenious techniques developed over millennia.

What is flannel fabric?

Essentially, flannel fabric simply refers to any cotton, wool, or synthetic fabric that fulfills a few basic criteria:

Softness: Fabric must be incredibly soft to be considered flannel.

Texture: Flannel has either a brushed or unbrushed texture, and both textures are equally iconic.

Material: While many materials can be used to make flannel, not all materials are suitable for this fabric. Silk, for instance, is too fine to be made into flannel, which is supposed to be both soft and insulative.

Flannel in history

It’s believed that the word“flannel” emerged in Wales, but we know for a fact that the term was in common usage in France in the form “flannelle” as early as the 17th century. While flannel was periodically popular among the French and other European peoples throughout the Enlightenment era, interest has waned elsewhere while Welsh flannel use has only increased.

Flannel today

These days, types of flannel are often known by their association with certain Welsh towns or regions. Llanidloes flannel is very different from Newtown flannel, for instance, and Welsh flannel varieties vary significantly from all other European flannel types.

Blanket

Sheet, usually of heavy woolen, or partly woolen, cloth, for use as a shawl, bed covering, or horse covering. The blanketmaking of primitive people is one of the finest remaining examples of early domestic artwork. The blankets of Mysore, India, were famous for their fine, soft texture. The loom of the Native American, though simple in construction, can produce blanket so closely woven as to be waterproof. The Navaho, Zu?i, Hopi, and other Southwestern Native Americans are noted for their distinctive, firmly woven blankets. The Navahos produced beautifully designed blankets characterized by geometrical designs woven with yarns colored with vegetable dyes. During the mid-19th cent. the Navahos began to use yarns imported from Europe, because of their brighter colors. The ceremonial Chilcat blanket of the Tlingit of the Northwest, generally woven with a warp of cedar bark and wool and a weft of goats' hair, was curved and fringed at the lower end. In the 20th cent., the electric blanket, with electric wiring between layers of fabric, gained wide popularity.

How to Properly Use a Bath Mat

Whether you’ve just remodeled your bathroom or you’re looking to spruce up your existing space for the season, accessories like a handsome bath mat, perfectly patterned shower curtains, or the plushest of bath towels will take the room from everyday necessity to serene spa destination. While just as important as the others, the lowly bath mat can get overlooked. But don’t make the mistake of opting for the first white terrycloth style you see. The right bath rug won’t just help you avoid the unpleasant shock of stepping onto bare tile after a shower. It will give your floor—and the whole room—an extra hit of much-needed personality. Here, we’ve gathered bath mats that are soft, absorbent, and beautifully designed. Think geometric prints, cheery stripes, even a cheeky banana-shaped option—plus many more.

First off, everyone had some great suggestions as to why we use bath mats at all. They soak up water, yes, but they also keep us from slipping and smashing our heads through the toilet, and act as a temperature buffer for our toesies between the hot shower and the ice cold floor. Gee, bath mats are pretty swell!

When it came to usage, the general consensus was that this is the wrong way to do it:

Finish shower

Step out onto mat

Grab towel

Then dry off

It leaves the bath mat soggy and wet for whoever showers after you. It also makes you much colder during the drying process.

Most people seemed to agree that this is the right way to do it, though:

Finish shower

Grab towel from inside the shower

Dry off inside the shower

Then step out onto the mat

But you all suggested a few excellent additions, like keeping your towel within arm’s reach of the shower so you don’t have to get cold to grab it, squeegeeing your hair and body to remove excess water before you dry with a towel, keeping the curtain or shower door closed while you dry off to stay warm, drying off from the top down (hair first), and hanging up the mat over the edge of the tub or shower when you’re done so it can dry without looking like a random wet towel on your floor.

What is the Difference Between Fleece and Flannel?

As you already know, the main difference between fleece and flannel is what they are made of. Fleece has synthetic fibers, and flannel features loose cotton threads. But because of their different fibers, these fabrics and finished products have several unique characteristics.

Take a look at this in-depth comparison of key features such as warmth, softness, and sustainability for each type of fabric.

Warmth

Most of the time, fleece has a thicker nap and also provides more warmth than flannel. Now, flannel is quite a cozy and warm fabric in its own right! But in comparison, fleece usually wins the warmth contest.

The exception to this rule is that some high-quality types of flannel contain wool fibers, and these types of flannel provide intense warmth!

What makes fleece so warm? Its many tiny, raised polyester fibers trap heat and hold them in the loose, velvety surface of its pile. If you have ever stuck your hand into your dog’s fur in the middle of winter, you know how all those tiny hairs hold immense warmth against your pet’s skin! Fleece fibers work the same way when you wear them against your skin.

Softness

Fleece is often softer than flannel, but if you have sensitive skin, you may find that its synthetic fibers also have a slightly plasticky feel. Of course, you will find exceptions to this rule, especially in flannel made with silk fibers. This will probably feel much softer than even the softest fleece!

Because both types of material go through a napping process, they both feature an incredibly soft texture on at least one side of the material. Fleece usually has a thicker, deeper pile, while flannel has a faint fuzziness on top of its woven surface.

If you rest your hand on top of the fleece, you feel as if your fingers can sink into the thick surface, at least a little. When you rest your hand on a piece of flannel, you typically feel a cozy fuzziness.

Blankets

Both fleece and flannel make excellent blankets and throws! You can find soft, pretty fleece and flannel blanket in pretty much any color or design you want.

That said, you should probably go with flannel for a baby blanket, as synthetic materials can sometimes cause allergic reactions.

If you plan to sew a blanket, though, you will want to use fleece. Flannel unravels super fast due to its loose weave, making it challenging to cut and sew. Fleece does not unravel when cut because it has a knitted construction with threads looped over each other.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

fic: brick by brick (2/10)

fandom: danganronpa

characters/pairings: fuyuhiko kuzuryuu, peko pekoyama + the SDR2 survivor squad. kuzupeko. tags for other plot-relevant characters will be added on AO3 as chapters are posted, yadda yadda.

rating: m

summary: They meet again, after the Neo World Program has torn them to their foundations: hope, despair, and the yawning debt of their history, waiting to be answered. It's up to them to rebuild, from the ground up, no matter how difficult the work or unfamiliar the tools.

No one can lay the mortar of your recovery but yourself.

read on AO3

Owari brings her a fresh change of clothes, the morning she’s to be discharged from the hospital. It’s all plain, loose polyester: socks, underwear, a black t-shirt, and elastic black pants. The sneakers have their laces pre-tied, the knots loose enough that Peko can slide her feet into them without having to undo them.

She holds them in her lap and looks at them. The laces are dark blue, their loops perfect.

“They’re all like that,” Owari says from the doorway. “Hinata’s been doing it since day one. I wanted to deck him when he gave me mine. Almost cracked my head open on the floor!”

Peko thinks she’s meant to find humor in the story. Owari is smiling while she recounts it, at least. She’s braced diagonally in the doorframe, feet on one side and shoulders on the other.

She’s small. It’s never been a word Peko thought to apply to her before, with all her height and muscle and force of personality, but while most of them are already some degree of too-thin, Owari toes the line of emaciated. Her jaw is sharp and prominent. The bones of her elbows jut out from beneath her skin.

“Hurry up and put ‘em on,” she says. “This place gives me the creeps.”

Peko agrees. She leans down to set the shoes on the floor, and wriggles her feet in toe-first. It takes longer than it should. If Owari notices, she doesn’t say so.

Ostensibly, she’s come to help move Peko’s things into her cottage. But Peko’s ‘things’ amount to a single box of trinkets she doesn’t want to keep, including the clothes she was wearing when she was brought out of the pod.

Owari hands her the box anyway. The heaviest item is the box itself, and it still strains the flexors in her forearms. When she stands up from the bed, her right elbow burns.

(The blade caught on a ligament on its way in. It twisted when it was removed, shredding skin and muscle.)

“You got it?” Owari asks.

Peko nods. She doesn’t redistribute the weight of the box in her arms; it is not heavy, and the damage is not real.

“Alright! Then let’s blow this joint!”

It’s easier said than done; the islands all feel more spread out than Peko remembers them being. She can’t tell if that was an intentional aspect of the simulation, or a shift she missed after being eliminated so early from the game, or if it’s merely a function of her fatigue, each step taking more effort than it should.

It’s a rare, cloudless day. The sun bears down on her, heat soaking into her dark clothes.

“You good?” Owari calls back to her.

“Yes,” Peko answers.

By the time they’ve crossed the first bridge, the burn in her elbow has spread up her bicep and into her chest. She takes small breaths; if she breathes too deeply, it’s like her sternum is splitting down the middle.

(The blade sunk in at an angle, pierced her arm and then sunk further, between her ribs. It punctured her right lung.)

Peko concentrates on keeping her grip on the box, and on putting each foot on even ground. Ahead of her, Owari is telling a story that sounds like it might still be about Hinata and his pre-emptively tied sneakers, but Peko can’t be certain. The sound of her voice is murky and out of focus, and it’s difficult to sort detail from noise.

Her hair is in her face. It sticks to sweat on her neck and the underside of her chin. She wants to push it back, but curls her nails into the flat edges of the box instead. It’s a situation she’s put herself into. She’ll get relief from it when she learns to braid her hair again.

Until then, she keeps her breathing shallow. She thinks herself through each step, and does not think about how she’s sweating much more than she should for the temperature, humidity, and level of effort.

The narrow scope of her concentration clouds her peripheral vision; it’s inevitable that she eventually collides with something, headlong. The box jostles painfully against her ribs, and she almost loses her balance in the shifting dust of the road. When she raises her head, the something is Owari, one hand hooked around the top flap of the box.

“Hey,” she says. “We’re gonna take a break.”

“I would prefer not to waste time,” Peko answers.

Owari ignores her. She leaves Peko where she is and sits on the side of the road with her legs splayed out in front of her. She leans back on her hands to frown up at the clear gap of sky above them, and doesn’t say anything else.

“I’m fine, Owari,” Peko says.

This central island was grassy and manicured, in the simulation. Here it’s cracked and barren, mostly loose dirt and little else. Owari still flops back into it, arms spread out and smeared with dust.

“I know you are,” she says. “Ain’t sayin’ you’re not.”

She says it so plainly that Peko can only take her at her word.

“Coach used to get on my case all the time,” Owari goes on, after a few long seconds of silence. “‘Bout how I’m not supposed to use up all my strength in one go just because I can. It’s stupid, right? Like, if I can take somebody out, I should just take ‘em out, and if I can’t, then I should do as much damage as I can. Why waste a bunch of time dragging it out?”

Peko understands the parallel she’s trying to draw. It’s clumsy, but self-explanatory. “I understand,” she says. “But in this case—”

“A couple minutes,” Owari says. “Then we’ll go.”

Peko closes her eyes, and breathes in. Her chest burns, but in the time they’ve been delayed it’s dimmed from piercing to merely discomforting.

“... Fine.”

She opts to stand while she waits.

*

The cottages are not assigned. Hinata had emphasized that detail, when he first informed her of her discharge.

“You’ll have a choice,” he’d said. “There are plenty still open.”

Regardless, Owari turns down the left side of the walkway when they arrive. The others have clustered their choices together; the left section is nearly full, leaving the right one completely empty.

It makes sense, from a strategic perspective. The cottages are more defensible when they’re together, and there’s no reason to believe the fifteen of them wouldn’t be targets, even in a remote place like this. With so many of them as vulnerable as they are, any advantage is one worth having.

Peko hovers at the fork of the walkway all the same.

There is one cottage left available on the main side, all the way at the end. It was Hanamura’s in the simulation, Peko recalls. He’d apparently opted to take Tanaka’s instead, when it was his turn.

(Tanaka remains in his coma, with no signs of recovery yet. Peko understands that everyone who is still incapacitated is either a killer or a victim.

She also understands that she has upset the ratio of those awake.)

Owari realizes Peko hasn’t followed her only when she reaches the door. “Hey!” she calls. “What’s up?”

Peko turns down the right side of the walkway. She follows the row of cottages almost to the end; it feels otherworldly and strange, familiar and not. Second to last, on the right. This one was hers, in the simulation.

She balances the box against her hip just long enough to test the doorknob. It swings open without protest. They’ll need to get keys for the locks.

Owari comes up behind her. “This the one you want?” she asks. She sounds skeptical.

Peko looks in from the doorway. None of the personal touches that had been added for her in the simulation remain; it’s sparsely furnished, and coated in dust. She imagines the others are in largely the same condition.

In the simulation, the young master had spilled Koizumi’s photos across the floor of Peko’s cottage. It had been a bright, cloudless day like this one, as picturesque as all the ones before it. She had recognized the photos for what they were, or thought she had: a collage of Koizumi’s missteps and the young master’s anger.

He didn’t remember the incident depicted in the pictures. Peko hadn’t, either.

She remembers now.

She says, “Yes.”

*

Owari stays with her through the afternoon. “I’m s’posed to keep an eye on you so you don’t wander off again,” she says, straightforward, and Peko is in no position to argue. The concern is valid, with her recent behavior.

There’s more to be done, either way. Months of neglect have left the cottage caked in dust and dirt; the sheets of the bed need to be changed, and the mirrors in the bathroom wiped down. Hinata had warned her about the state of it. The others haven’t had time to comb over the other cottages, just yet. There’s too much to do and not enough hands to do it, he’d said.

It’s fine. It’s only right that she contribute.

Owari brings supplies in from the other cottage: brooms and rags and fresh linens. Her sweeping and dusting is halfhearted at best, but that’s fine too. Peko bridges the gap herself; as degraded as they are, her muscles still remember the motions. It’s thorough, repetitive. It gives her mind the opportunity to retreat somewhere warm and still and silent.

It’s late in the day before she’s able to start on the bathroom. She has to clean the mirrors in slow, methodical pieces; her lungs burn when she raises her arms above her head, and dark splotches cloud her vision if she keeps them that way for too long.

(The blade came from above and behind. It shattered her scapula and then lodged itself in bone; it had to be wrenched out like a pry bar, back and forth, back and forth, back and forth.)

“Heyyy!” Owari whoops from the other room. “Look who it is!”

Peko has only half the mirror finished. The reflection of the front room is grimy on one side, but the image is clear enough: the young master stands in the open doorway of the cottage, looking at her.

His gaze jumps away as soon as she makes eye contact. He has a box cradled against his chest, the top flaps folded together to hold it closed. His hands are full, so he and Owari exchange a friendly bump of elbows.

“Yo,” he says. “How’s it going?”

Owari leans against the doorframe, and squints appraisingly back into the room. It’s just as empty as it was when they arrived. “Pretty good,” she says. “We’re pretty much done. What d’you think, Pekoyama?”

“Yes.”

He looks at the room before he looks back at her. He seems preoccupied, but it’s difficult to tell; his face isn’t the open, expressive canvas it used to be. Or maybe it’s her, maybe she’s not as adept at reading what’s written there anymore. Maybe she never was.

When he does look at her, he can’t seem to focus on her face for longer than a moment or two. “Right,” he says. He shuffles at the threshold of the door. “Well, I... Uh, I brought this for you, Peko.” He lifts the box up. “I had it, so… Figured I’d save you guys the trip.”

He isn’t coming inside, so she leaves her rag in the sink and goes to him. (With her mind drawn back to the forefront, she feels the grinding objection in her knees.) She doesn’t recognize the box, and it isn’t labelled, aside from her surname written on it in permanent marker. It’s his handwriting.

“What is it?” she asks.

“It’s the stuff you had on you when the Future Foundation picked us up,” Owari tells her. “Kuzuryuu put all the boxes together. He hides ‘em in the back of that smelly old hotel building.”

“It’s not smelly,” he says.

Owari grunts. “To you, maybe.”

“And I don’t hide them, either. Are you missing the whole point on purpose?”

“What’s in it?” Peko asks.

He looks down. There is a small gap in the top of the box, where the bent flaps aren’t fully flush, but the shadows are too deep for her to properly see inside it.

“Just a buncha crap,” Owari says. She sounds bored. “Mine was mostly clothes.”

“Clothes,” he confirms. “And- other stuff. I don’t know if…” He jostles the box higher in his arms. Something metallic clatters inside. “Just, you should get to decide if you want to look at it or not. And what you want to do with it.”

“Do with it,” Peko repeats. “Like what?”

Owari counts on her fingers. “I trashed mine. And Hanamura’s, ‘cause he asked me to. Mioda and Souda burned theirs, Sonia threw hers out into the ocean, and Hinata and Kuzuryuu kept theirs.” She tilts her head in his direction. “Right?”

His only answer is, “Yeah.”

Peko holds her arms out. “I’ll take it.”

He’s careful not to touch her when he hands it off, which makes the hand-off clumsy. The weight put on her biceps is uneven, and the right one buckles unexpectedly. The box sinks sideways, which sends the contents sliding inside, which makes the weight distribution even more uneven.

“Shit.” He fumbles. “Sorry. You got it?”

She braces the bottom of the box against her stomach. She manages to answer, “Yes,” but even she can hear the grit in her own voice. He doesn’t believe her.

“Here,” he says, and shuffles forward to take on some of the weight. “Let me—” His hands slide between hers on the underside of the box. The edge of his pinky brushes the inside of her wrist. She remembers his lips tasted like sea salt.

Her muscles spasm. It’s the only explanation she has for how her biceps abruptly contract, twisting pain up into her shoulder. It jerks the box out of his hands, and sends her stumbling back a step and a half. She can feel Owari’s hand hovering at her back, a spotter’s safety net.

His face has changed, but she can’t read him well enough anymore to know what it means. She watches the way his mouth forms around the initial plosive of her name— and she cannot think about his mouth in that context.

(He wishes it didn’t happen. Therefore, it did not happen.)

“Thank you,” she says, before he finds the sound.

His jaw snaps shut. He returns his hands to his pockets with a slow, deliberate roll of his shoulders. “Right,” he says. “Sorry about the— yeah.” He clears his throat, and looks at Owari. “Anyway, I... I gotta get going. Got Souda up my ass about a bunch of resistors we don’t have.”

Owari misses his cue. She says, “Okay?” and looks at Peko for confirmation.

For a moment, he doesn’t leave. He lingers in the doorway and looks at her too, gaze finally steady on her face. There is something to say. It crowds the breath in her throat, but she doesn’t know what the words are.

“Thank you,” she says again.

He nods. He leaves.

Peko sets the box on the floor, next to the one she and Owari brought from the hospital, and returns to the bathroom.

*

She doesn’t sleep any better in the cottage than she did in the hospital.

She tries. She lies in her bed, on top of the sheets, and closes her eyes. She gets as far as the hazy half-place between sleeping and waking, when her measured control over her muscles and her mind begins to unravel.

She is seventeen and beginning her third year of high school. Her skills are at their peak, but the young master turns them away. He calls her ‘Pekoyama’ in front of their classmates. She is always working harder to be what he needs.

She is sixteen, and the sea around Jabberwock Island gleams pink in the morning sun. The young master clashes with the other students. He picks fights and makes threats and isolates himself. She worries for his safety.

She is nineteen, and the world is over. She pins a dog to the ground with her sword, the blade pierced through the muscle of its back leg. It whimpers and whines, its claws scrabbling uselessly in the dirt. She waits hours, until it stops moving.

She is twenty-one, and she is alive when she should be dead.

She is all of them, and none of them. In that place of half-sleep, the well-defined edges of her mind lose their clarity. Memories seep across the boundaries like watercolors, mixing together until the colorless remains of her self are muddy and dark.

She is nineteen and escorting the young master to the morgue.

She is twenty-one and washing Koizumi’s blood off her skin in the shower.

She is seventeen and breathing in the smell of rot until she vomits.

She is sixteen, and wakes gasping.

She tries two more times. After the third attempt, it’s too late to try again; color peeks up from beneath the horizon, just visible through the slats of her window. She sits up on the mattress, legs crossed underneath her, and lets the silence crowd in from all sides.

The cottage isn’t any different from the hospital. It yawns around her the same, an empty swath of space. The colors are warmer, but the finish of the wood is still cold.

She rolls the heel of her hand against the outside of her thigh.

(The blade had been aimed at the small of her back, but glanced off the guard of another weapon. It only skimmed her leg, but the angle sent it gouging into the soft flesh beneath the young master’s ribs.)

The box Fuyuhiko brought for her is still at the end of her bed, the flaps still folded shut. It contains clothes, he’d said, and other things.

She gets up. She closes the shutters of the window, and peels off the loose t-shirt and shorts she wore to bed. She stands naked in front of the full-length mirror in the bathroom, and inspects the body that she’s in.

She doesn’t recognize it, from any angle. It’s the same as the muddy center of her mind, an unintelligible mishmash of diverging histories. She is too thin at her ribs but too full at her hips. Her hair is at once too short and too long. She recognizes some scars, struggles to recall others, and searches for still others that don’t exist at all.

She lays her palm flat against her stomach, where there is a purple, ragged cut arcing from her left hip to her ribcage. She draws her fingers up the line of puckered flesh and remembers: Munakata Kyosuke had in a rare moment gained the upper hand against her. He’d intended to kill her, and had come very close. Tsumiki had stitched it up while she was still awake, giggling, tracing spirals in the blood.

She twists at the waist. There is a swath of raised, shiny skin on the outside of her right shoulder, and she remembers: the young master had fired his gun point-blank into a crowd of people, the side of the barrel laid flat against her skin. He’d been aiming at nothing in particular. The crowd had only been a net to catch the bullet. All he’d wanted was to see her flesh bubble and to hear her scream, and he’d gotten frustrated when he only achieved the former. He’d hit her with the butt of his revolver, leaving a divot beneath her collarbone.

She dips her finger into the space. Fuyuhiko, her mind corrects belatedly. She regrets it as soon as she thinks it.

(She had responded. She struck him across the jaw with the hilt of her sword, hard enough to send him to the ground in a spray of blood and spit. He coughed and cursed into the dirt, and the crowd had taken the opportunity to scatter.

She stood over him, and touched the tip of her blade to the thin stretch of skin at the dip of his collarbone, over his trachea. She considered the ramifications of killing him, not for the first time and not for the last.

He sat up on his elbows, eyes bright, and laughed until his chest heaved. She’d had to draw her blade back, just a fraction; it wouldn’t do at all if he sliced his own neck open. “Hey Peko,” he’d said, between gasps. “Isn’t this perfect?”)

She refocuses on the mirror. It’s her face again; the current one, at least, or probably. She is twenty-one.

The box behind her is caught in the reflection. From this angle, she can read the block letters across the side. Pekoyama. She stares at it. She isn’t sure for how long.

Eventually, the sun rises.

*

Owari knocks early. “Woah,” she says, when Peko opens the door, “you look like crap.”

Peko touches her fingers to the half-moon of skin beneath her left eye. It’s entirely possible she does. “I didn’t sleep well,” she says.

“Oh, yeah, that.” Owari grins at her; Peko has already lost track of the number of times she’s done so since yesterday morning. “Don’t worry about it. It sucks the first few days, but it gets easier. Beds’re better here than the junk we’ve got up in the hospital.”

Peko doesn’t disagree, so she doesn’t say anything. Owari doesn’t seem bothered. She takes the silence for what it is.

“Anyway, breakfast is up at the lobby, if you want it,” she says. She jerks one thumb over her shoulder. “You remember how to get there, right?”

“Yes,” Peko answers. The implication isn’t lost on her. “... You won’t be coming?”

Owari hunches her shoulders. “Eh. The food’s pretty whatever, you know? Even Hanamura can only do so much with the crap we get. I’m not really feelin’ it.”

There was a shift in the conversation, somewhere. The interaction suddenly feels off, in a way that's difficult to pinpoint. Body language, or inflection, or— something. She doesn’t know Owari well enough to read her mannerisms.

She doesn’t know what to say, so she only says, “Alright.” Owari waves and leaves toward the beach, her spine bent and her arms pillowed behind her head.

Peko goes to the hotel by herself. She’s one of the last to arrive; Hanamura is using the reception desk as a workstation to ladle creamy oatmeal out into bowls, and the others congregate around him, half line and half crowd. The only exceptions are Sonia, who sits alone by the window, and Hinata, who has his laptop open on one of the derelict arcade machines.

Hinata is the first to notice her. He says, “Pekoyama,” sharply enough that the others all look at him, then swing back around to look at her.

The weight of six attentions trained on her at once, all varying degrees of surprised or concerned, presses her back towards the exit. She grips the edge of the doorframe to keep herself in place.

“Owari isn’t with you?” Hinata asks.

The room is quiet. Peko can’t read any of their expressions, so she settles for the truth. “She decided against breakfast this morning,” she says. She sees understanding light one by one across their faces, and still doesn’t understand. “Is something the matter?”

“Shit,” Kuzuryuu says under his breath.

Across the room, Sonia stirs. “She cannot be alone,” she says. It sounds like she reaches for her diaphragm but makes it only to her lungs, her voice breathy and unsteady. She smooths trembling fingers over her knees, but doesn’t manage to stand. “I… I should...”

“W-Wait.” Souda shoulders his way out of the skinny breakfast line. “I’ll do it,” he says. He reaches one shaking hand out in Sonia’s direction. “You stay here, Miss Sonia.”

Sonia lifts uncertain eyes, but doesn’t say anything. Kuzuryuu glances at her, then back. “You sure?”

“I… I was kinda able to get through to her the last time,” Souda says. “I mean, I think I get where she’s coming from. Kind of. Lemme go.”

No one objects.

Peko steps aside to let him pass when he reaches her. She doesn’t say anything, but something must show on her face, because he smiles at her, small and tight. “Don’t worry about it, Pekoyama,” he says. “You didn’t know.”

A gloom settles over the lobby, but the motions of the day don’t cease. Hanamura takes two bowls off the reception desk, and begins handing the remaining five out to the others. There is not one set aside for himself.

Mioda brings a bowl to Sonia. Hinata gets up to take his.

Kuzuryuu brings the last to her.

“Hey,” he says. He’s stopped a few feet away from her. “C’mon. You can come sit down.”

She’s still in the doorway, she realizes, with her fingers still wrapped around the frame. She lets go, and follows him to one of the lobby’s faded couches. He gestures for her to sit, so she does; he perches on the edge of the coffee table across from her, his knees catty-corner to hers.

“Here.” He holds one of the bowls out to her. She reaches up to take it from the bottom, and it warms her palms, just on the edge of too-hot.

“Thank you, Kuzuryuu,” she says.

There is a palpable stretch of silence.

He looks startled, confused, maybe hurt. She rewinds in her head to find her mistake. Did she not say what she thought she did? He specifically instructed her to use his name instead of his title, so that the other students wouldn’t—

Understanding clatters its way in, too late. (She is sixteen, and their professional relationship does not exist on this island.) When she finds the words to apologize, he’s already said, “Yeah. Uh, you’re welcome,” and dropped his gaze into his bowl.

She looks down at her breakfast. Even with supplies as meager as they are, it still looks appetizing, with a fluffy consistency and pale beige coloring. The others eat around her, spoons ringing against bowls at uneven intervals.

“So…” He clears his throat and bows his head. It’s to muffle his voice while at the same time disguising the fact that they’re having a conversation at all. It’s a familiar habit. “You look tired,” he says, and then ruins the effect by lifting his eyes enough to look at her. “I mean, did… did you sleep okay? Last night?”

Technically, he’s lifted only the one eye to look at her. Owari had talked about him wearing a patch in her more colorful and bombastic retelling of the simulation, and a hazy memory of one lingers in the recesses of Peko’s memories, but as long as she’s been this self, she’s never seen it. As far as she knows, he’s only worn the scar.

(She remembers: messy blood on her fingertips, the smell of copper in the back of her throat, and his strained laughter in her ears. Whether she was the one holding the blade or not is immaterial. It was always her responsibility to see him whole and unharmed.)

“It was… an adjustment,” Peko says.

He swallows a bite of his breakfast with a grimace. She imagines it’s bland, no matter how well it’s made. “Yeah,” he says. “I mean, I get it. I know what you’re talking about.”

His jaw works. He wants to say something else, so she waits. “Listen,” he starts, but the rest of the sentence flounders in his throat. He rubs at his temple. “Just… First thing, I’m not trying to bullshit you or anything. Okay?”

He’s focused on the empty end of his spoon, his brow pinched down. It’s important to him, whatever he wants to say. She doesn’t want to discourage him. “Alright.”

It takes him a few more long seconds to sort out the words. He drags his eyes (eye) back to her face, and the look he gives her is sympathetic to the point of intensity. It makes her want to break the eye contact, but she doesn’t.

“You know you can tell someone, right?” he says. “If it... gets bad. You don’t have to just tolerate it.” He hesitates, and when she doesn’t fill the space, finishes: “... Hinata has ideas for stuff that can help, sometimes.”

She doesn’t recognize him either, she realizes. She’s always known the kind, gentle core of him, but she’s never seen him let it sit so plainly on his surface, before now. The softer edges suit him the way she always quietly thought they might: compassion and leadership and responsibility.

She should be happy for him and the progress he’s made. She is happy. She is grateful to have the opportunity to see it.

She looks down at her lap, her throat tight. Her breakfast is starting to get cold.

The others finish up their meals. Mioda tells Sonia a story about a pair of singing alley cats on their way out of the lobby, their elbows intertwined. Hinata has sunk into his work, his shoulders curled over the keyboard of his laptop.

When she’s been silent long enough, Fuyuhiko sets his palm against his knee and pushes himself up to standing. “You should eat,” he tells her. “It’ll help. That’s not bullshit either, I swear.”

“I know,” she answers.

“Okay.” He looks back over his shoulder, and his frown flattens into a grimace. “Smack Hinata if he doesn’t wrap it up in a few minutes. I’m gonna be pissed if he puts you behind schedule.”

“I will.”

“Okay,” he says again. When he looks at her, the lines of his face are weighed back down. “Then... I’ll see you, alright?”

He leaves.

After that, it’s only her and Hinata left in the hotel; more precisely, maybe, only her and the rattle of Hinata’s typing. She scrapes at the edge of her bowl with her spoon.

If the oatmeal was appetizing once, it isn’t now. The consistency is cold and thick, and it slithers down her throat when she swallows. Queasiness bubbles in her stomach, and seeps up the back of her throat. She manages three bites before she can’t manage any more.

(She watched three separate blades pierce her stomach. The wounds gaped, and spilled black gastrointestinal blood out over the young master’s chest.)

She dumps the rest of the bowl out into the parched, empty garden behind the hotel.

*

She doesn’t need to rouse Hinata. He finds her when it’s time, his laptop tucked under his elbow.

“Pekoyama,” he says. “Are you ready?”

She nods. Being discharged from the hospital doesn’t mean she’s finished her regimen of physical therapy; the only difference now is that their sessions are scheduled in his cottage, instead of behind the closed door of her hospital room.

There is a table set up in the main room. At the center is the stack of coins they’ve been using for her fine motor control exercises. They come in various sizes, whatever Hinata could find: wide plastic medallions and individual yen pieces and small, smooth buttons.

They’re starting a new set of translational exercises today. Hinata shows her with one of the smaller buttons: passed to his palm, then back, then set aside. She begins with the largest medallion, and makes it one step down in the stack, to the fat 500 yen coin.

The metal is harder to keep a grip on than the plastic, and the smell of it on her skin makes her head ache. She fumbles the coin while passing it back up to her fingers; it hits the table at an angle and goes spinning to the floor.

She looks at it, tucked behind the leg of the table. It should be simple to bend to retrieve it, but the center of her back shrieks with pain, and objects to even tiny adjustments of her posture. Even now, with her body as unfamiliar to her as it’s become, she understands that picking the coin back up while still remaining seated is outside the range of her flexibility.

That’s where her memory ends.

When it begins again, the room is darker, and wind is rattling the cottage’s only window. Hinata has his laptop open on the table. He isn’t typing; he watches something on the screen, his chin set in one hand.

“You’re back,” he says, without looking up.

Peko looks down. The 500 yen piece is back on the table, stacked neatly with the other coins. They’re separated into piles, organized first by color and then by size.

“You were gone for a while,” he tells her. “... I got bored.”

Some of the flatness in his tone and expression wrinkles. After so many weeks of sessions, she’s learned to read embarrassment in it. His wrinkles are the only parts of him that are still Hinata, flickers of color against a monotone background. Some days he is nothing but wrinkles. Most days he is nothing at all.

It upsets some of the others, Fuyuhiko especially. But to Peko, it’s one of the few things that still makes sense.

She watches him snap his laptop shut and rearrange the coins back into a single pile. She doesn’t apologize for wasting his time. It would change nothing, and she isn’t in a position to promise it won’t happen again.

Hinata pushes the stack of coins to the center of the table. She’s reaching across to take them when he says, “We don’t have to keep doing this, you know.”

She looks up at him. His wrinkles have smoothed back into nothing.

“Does it still hurt?” he asks.

(The blade dug up from below, clipped past her spine at the center and cracked her third and fourth rib on the right side.)

The shriek has calmed to a hum, but it’s still there, a steady distraction. She doesn’t need to answer him. He must read it in the wrinkles of her own expression.

“You’re well enough now to help with the basic maintenance of the island,” he tells her. “Endurance will come back on its own. If that’s all you want, you don’t need this.” He opens his hands above the stack of coins. She looks at them, mismatched colors and uneven sizes.

“But,” he goes on, “if you ever want to improve— actually improve— you have to learn to let go of it.”

(The blade lodges in her neck. It fills her throat with blood. She can’t breathe, can’t speak, can’t see.)

“If you don’t…” Hinata shrugs. “Then don’t.”

She is seventeen, and Satou Yume’s skull shatters against a metal baseball bat before she can intervene. The day after it’s done, the young master tells her he feels better.

She is sixteen and about to die. She holds her chin up, but makes the mistake of looking over her shoulder when the young master screams.

She is nineteen, and every member of the main branch of the Kuzuryuu family is dead except for one. She helps him drag their bodies out into the garden, where they can be left for the crows.

(It was her responsibility to see him whole and unharmed.)

She stands up from the table. Hinata says nothing when she walks out the door.

#peko pekoyama#fuyuhiko kuzuryuu#kuzupeko#danganronpa#PHEW#really hope i caught all the mistakes in this one#my headache is deteriorating fast but i really wanted to get it up#CHUG CHUG CHUGGIN ALONG#fic: brick by brick#sunwrites

28 notes

·

View notes

Photo

I recently got home from a trip to Nepal to do the Ama Dablam Base Camp Trek with seven other women.

One of my friends from a group I hike with, planned on doing this trek and asked if I wanted to come along. I’ve wanted to visit Nepal for a while so I jumped at the chance, booking annual leave from work for the following year when we planned to go.

She had heard that this particular trek was the most beautiful one to do in Nepal and, not that I’ve done any others, but I’d have to agree.

Where is it located?

Ama Dablam is located in the Everest region with most of the trail being on the popular Everest route. Then with about two days walk to the top, the trail turns off on its own path and becomes less crowded.

Our destination – the beautiful Ama Dablam.

Using a tour company

My friend who organised the trip opted to use a tour company by the name of Keep Walking Nepal, and I’m so glad she did! Everything was taken care of for us and they looked after us so well. All we had to do was arrange our own flights to Kathmandu. The company picked us all up from the airport (even those who were on a different flight) and took us to our hotel which was all arranged by the company.

We had an itinerary planned for the trip that included days of leisure either side of the trek which was great for sightseeing and shopping! We had some nice dinners together before and after the trek while in Kathmandu and even had a city tour included for us.

Having almost everything taken care of for you is something I would highly recommend.

Difficulty level

The Ama Dablam Base Camp trek is an 11-day trek and is rated at a moderate difficulty level, so a reasonable level of fitness is required. We were never really told the number of km, they just worked off time so I’m still not sure how many km the trek is all up.

Most of the days were fairly short with a couple of them done by lunchtime. We walked at a fairly slow pace and even slower on the inclines.

A snap of me with Ama Dablam in the background.

Here’s a copy of our itinerary:

Day 1 – arrive in Kathmandu (meet and greet)

Day 2 – sightseeing in Kathmandu

Day 3 – fly to Lukla, trek to Phakding (approx 3- hrs)

Day 4 – trek to Monjo (approx 3-4hrs)

Day 5 – trek to Namche Bazaar (approx 4-5hrs)

Day 6 – rest day at Namche Bazaar

Day 7 – trek to Deboche via Tengboche (approx 5-6hrs)

Day 8 – trek to Mingbo (approx 4-5hrs)

Day 9 – trek to Ama Dablam Base Camp then to Pangboche (approx 4-5hrs)

Day 10 – trek to Phortse (approx 3-4hrs)

Day 11 – trek to Khumjung (approx 3-4hrs)

Day 12 – trek to Monjo (approx 5-6hrs)

Day 13 – trek to Lukla (approx 4-5hrs)

Day 14 – fly to Kathmandu, rest of day at leisure

Day 15 – trip concludes

There were a few steep accents but the guides take it really slow so that it still remains enjoyable. Of course, if you really wanted you could go ahead which is what one or two of the women in my group did on occasion.

Our group when we made it to base camp!

Fitness and preparation

To prepare for my trip, I would do laps of my local lookout. This has quite a steep but short accent so I’d do a few of them a couple of times per week. I was worried about my fitness level before my trip, but they take it quite slow that I don’t think it’s much of an issue. If you can handle the odd mountain climb at a slow pace then you’d be fine.

You will need to do some training before your hike, just so you’re in good shape.

Acclimatisation

Ama Dablam Base Camp is at 4600m so acclimatisation on the way up is required to reduce the risk of altitude sickness.

We had a rest day (even though we didn’t rest) in Namche Bazaar at 3440m high to help with acclimatisation. On our rest day, we climbed up to the Everest View Lodge at 3880m, had a drink and came back down.

You will stop along the way to help acclimatise on the trek.

Vaccinations

After visiting my doctor and telling him where I was going, he suggested I start the Hep B shots as well as a Hep A/Typhoid combination shot. Though, it’s worth checking with your doctor as they might recommend something different for you.

Permits

As we do enter the Sagarmatha National Park I believe that you would need some sort of permit but this was all taken care of by Keep Walking Nepal.

The Lukla airport is where most people begin their Mt Everest or Ama Dablam Base Camp treks.

Costs for the trip

The price of the trek itself is $2080 USD but we were asked to put down a $500 USD deposit out of that total price to book our place.

The rest could be paid in cash when we got there. I had the remaining exchanged into US dollars so I could hand it over as soon as I got there.

My flights cost me $1087 to Kathmandu return from Adelaide flying with Cathay Pacific.

I had to renew my passport so that was another expense.

We were told to have the right cash in US dollars for our visa which was a 30-day visa costing $40 USD. We just went over the 15-day visa option as we had a couple more days either side of the trek in Kathmandu, otherwise, a 15-day visa costs $25 USD.

The rest of my trip expenses went on tipping my guides and porters (our tour company suggested $8-9 USD per person per day but more or less is up to you) and spending money. Everything over there is a lot cheaper than in Australia. If you allowed as much as you would for any other holiday, then you should have enough spending money.

The good thing about using a tour company is that the costs include almost everything.

Our porters

We had a 10kg limit for stuff we didn’t want to carry with us during the day but wanted on the trek that the porters carried for us. I packed super light as I didn’t want to load my porter up with much. All I used for the trip was my day pack, so I just gave my porter a small packing cell of my clothes to carry.

Some of the other women went over their 10kg limit, so they ended up putting some things in my bag. All the weight got shared around so it ended up working out well.

As we used porters, it meant we didn’t have to carry much gear.

Gear to bring

There’s a video I made on my YouTube channel of everything I took on the trip and how I packed my pack if you want to check that out.

The following is the list we were given to use as a guide:

Hiking boots – preferably worn in but with good grip.

Lighter weight shoes or Hiking socks – 4 thick, 3 lighter weight pairs

4 or 5 Lightweight trekking shirts or t-shirts. During a trek day you will get hot so it’s good to carry a spare in your daypack.

1 heavier weight top – sloppy joe or heavier jumper

2 to 3 shorts or trekking trousers

Underwear – 5 pairs comfortable – cotton/polyester – just be careful to avoid friction (chafing)

Toiletries – usual essentials (include some soap) but it’s also good to bring wet wipes as they’re very useful

Our tour company provided a down sleeping bag, a down jacket, and toilet paper in a kit bag, along with the rest of your gear that the porters carry.

Spring is a great time to visit, as the weather is good and it’s not as busy.

What’s the best time of the year to go?

There are two main trekking seasons in Nepal: Spring and Autumn. Their Autumn (September to November) is the most popular trekking season as mountain views are at their best, however it is incredibly busy!

If you’re not a huge fan of snow then I’d recommend going when we went, which was late April – early May. That’s their Spring and it’s beautiful there. On our trek, we saw so many gorgeous rhododendrons (their national flower) in full bloom. It was stunning!

We went in spring, so we experienced the beautiful rhododendrons in bloom.

Let’s talk about food

It was recommended to bring any snacks we might want during the day and carry them in our day packs, however, we were fed so well that none of us really ate our snack food at all!

The snack food that I took with me consisted of mixed nuts, beef jerky, dark chocolate, lollies and Clif gel shots, which I did actually have before a couple of the big climbs to give me more energy.

We had breakfasts of pretty much whatever we wanted, whether it be toast, cereal, eggs, pancakes etc. Then we had a cooked lunch, dinner and dessert every day! We ate so much food!

The menu consisted mainly of soups, egg meals such as omelettes, pasta, and traditional dhal bhat and momos. My favourite momos were the cheese and potato. Delicious!

We took our own snacks, but we didn’t even need it as we were fed so well.

Accommodation

The Ama Dablam Base Camp Trek is an 11-day lodge-based trek so we stayed in lodges and tea houses.

The rooms were always twin share with about half of them having a bathroom as well. Most of the showers were free. There was only one place that charged us for a shower but as we each got a big dish of hot water in the morning we didn’t really need to pay for a shower.

The beds were always made up with a sheet and pillow and usually had a thick blanket or quilt folded up on the end. We were provided with sleeping bags and took our own sleeping bag liners but sometimes we needed the blanket or quilt on us as well.

The view from my lodge on the first day of my trip.

I didn’t want to go home!

If you’re thinking about heading over to Nepal for a trek, I strongly recommend you consider the Ama Dablam Base Camp Trek with Keep Walking Nepal.

For a whole video series on my adventure, head to my YouTube channel, where I break each day into a short video of the trip.

If you leave during April, you’ll see their beautiful flowers out in bloom everywhere and it’s not too cold. I hate the cold and even though it snowed on us one day, I still enjoyed it.

After wanting to make a visit to Nepal for some time, I would say that Ama Dablam Base Camp trek was definitely worth the journey.

Happy escapades!

Out of all the spectacular treks that Nepal is known for, which one is your favourite?

The post Guide to Ama Dablam Base Camp Trek in Nepal appeared first on Snowys Blog.

0 notes