#i could write an essay on these two frames paralleled with this painting

Text

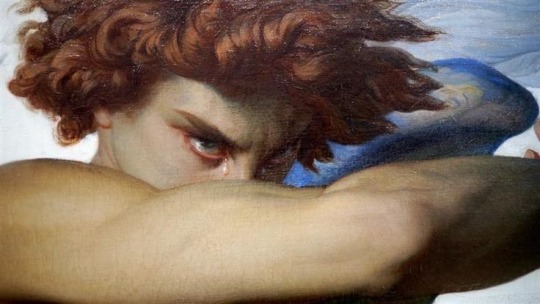

aegon ii targaryen (house of the dragon - “the green council” 01x09) / sansa stark (game of thrones - “fire and blood” 01x10) / fallen angel, oil on canvas, by alexandre cabanel (1847)

#the imagery… the symbolism!#i could write an essay on these two frames paralleled with this painting#hotd#house of the dragon#game of thrones#sansa stark#aegon ii targaryen#art#GoT#my uploads

178 notes

·

View notes

Text

My Three Page Pseudo-Essay on How the Kirby Anime Would/Should Be Made Today

This was written due to @hedeservesbetter tagging my post with “i woukd [sic] love to read this[, Akira]”.

Let me start off by saying there is a little more to this essay than what the original post says. We’re going to touch a number of topics not listed in it, but those are my biggest ideas. Let’s all also note the I don’t hate the Kirby anime. People accused me of hating the anime or trying to make it edgy the last time I made a post like this, and I still don’t understand why. It’s my favorite anime, probably. If it isn’t, it’s up there with Paranoia Agent and Perfect Blue as one of my favorites. Also note that the two “main” versions of the anime (Japanese and English) blend together in my head, and I’ll talk about both of them as though they are the same (because, honestly, you’re kidding yourself if you think they aren’t), but if I need to specify the version, I’ll use their full titles (Kirby of the Stars and Kirby: Right Back at Ya, respectively).

To say that nearly any animation that was made before the late 2000’s wouldn’t be better if it were made today is lying to yourself. There is so much technology we have today that we didn’t have before then. There’s a very big chance that if the Kirby anime was made today, it could be 100% 2D animation instead of half-3D like it was. That’s only possible because of programs like Flash or Toon Boom, which allow 2D animations to be made easier and faster. Most of the reason that characters like Kirby or King Dedede were animated in 3D half the time was to cut costs and development time. It’s hard to draw so many perfect circles and curved lines almost the exact same on every consecutive frame, but this downside is entirely negated by the use of digital animation tools, which allow you to copy shapes from one frame to the next. My sentiments seem to be echoed exactly by the development staff on the anime. Here’s a quote from Yoshikawa Souji (director and a writer on the anime), translated by Ivyna J. Spyder:

“3D is a way to increase the number of frames. If you make a 3D model once, then you are able to make efficient use of that. [...] [I]f it’s 3D, because you make a model, you can make movement from just clicking it.

“Therefore, the animator doesn’t have [a] hard time with drawing and can instead devote their time to movement, and it’s easy to get information of production and camera. [...] Already, it has 3-5 times the movement of normal TV anime.”

There’s also the option of it being a 100% 3D anime, like its 3DS-exclusive short, Kirby 3D. Being made only in 2012, the 3D already looks so much more competent. Of course, I can also point to the many fully-3D cutscenes that have been in Kirby games since then, the best-looking being the ones in Kirby: Star Allies. It’s very obvious that Nintendo has been becoming more competent with its 3D animations and models very quickly, considering their almost company-wide switch to 3D games, as opposed to 2D. Even with a television budget, ignoring the fact that Nintendo and HAL have infinite money to throw at anything they wish, this could still happen. A lot more fully-3D cartoons and anime have been popping up lately, including the visually gorgeous Land of the Lustrous and Miraculous Ladybug.

God, that’s a lot of words to just be talking about animation. And I haven’t even gotten to the part I started this essay to write! Let’s get on with that, shall we?

Escargoon is my favorite character in the Kirby anime, and right now, is my favorite character of all time. While that’s always subject to change, I suspect he’ll always be in the top ten. Anyone who knows anything about me knows I love this guy. I’ve even gotten others who don’t even know of the Kirby anime to love him.

Which makes me infuriated that he’s treated so badly.

You may have noticed I didn’t mention a certain penguin king in that sentence, even though he’s the one most associated with torturing Escargoon. But the truth is everyone, even the anime itself, seems to love to torture him. I don’t get it! I like the gay snail! I think he’s neat! And I’m sure at least a few of the writers and animators do too! So why does he get deprived of sleep and basic self care because “Haha, it’s funny to see him obsess over a robot”? Why does he get possessed by Erasem, causing him to go nearly insane from being forgotten by everybody? Why does he get abused by his boss so much it actually unsettles him when he treats him nicely? I don’t get it! I want good things to happen to him. I don’t want to watch him go insane from something out of his control every thirty episodes. Dedede isn’t treated like this, and he’s worse than Escargoon, objectively.

The anime starting with Dedede being nicer to Escargoon is a really, really good way for this issue to be remedied. Not only is the trope of a villain power couple way more interesting than “man in power beats his assistant who is clearly in love with him in Kirby of the Stars and has a choice to leave at any time in both versions, but doesn’t for some reason”, the latter is just unnecessarily cruel. Even if they don’t date or whatever, Dedede and Escargoon working together to formulate plans would actually be a force to be reckoned with, instead of making everyone that watches the show think “If Dedede is such an idiot, and Escargoon hates him, why haven’t the Cappies just killed him or something?”

Of course, you can have this and have the Escargoon torture porn episodes. Or! Just… don’t. Or make Dedede have an equal amount. Or is Dedede is still “more evil” in this scenario, make him have more. Listen, if Escargoon is still half-good like he is in the anime we got, he doesn’t deserve torture. I never understood this trope. Why do awful things happen to characters that aren’t actually terrible people? Especially for entire episodes?

I digress.

Let’s talk about Sirica. The fan favorite who was in... two episodes (or three in Kirby of the Stars)?

HELLO?

Are you insane, Kirby anime? Why is this character shelved for most of the series? She’s so goddamned cool! Are you OUT OF YOUR MIND? You packed this much character into one episode and not only is she shelved afterward, she doesn’t even get a satisfying ending so GODDAMNED KIRBY CAN BE COOL? This is not even addressing the fact that her mother died to make Meta Knight look cooler! You can read an excellent post about everything I’ve said here, said in a more compact way, but...

I feel like I’m going to scream at the top of my lungs!

I’m so sorry, Sirica. Let’s talk about how we can fix this.

First. Just put her in more episodes! It’s absolutely not fair that I can glean more character from her one episode than I can for Knuckle Joe, and he’s got THREE, but she still isn’t used! I can even think of an episode description right now, in like, two minutes. Here I go: The monster of the week needs to face an opponent who can change tactics quickly. We think Kirby can do it, but it’s still too strong. But wait! There’s a character with a SHAPESHIFTING GUN who can help Kirby defeat the monster! And the day is saved because Sirica is a relevant character in this scenario. It even draws a parallel to the Masher episode. This could also be fun to explore because Sirica is really stubborn and she might just straight-up refuse.

Also what’s up with Galaxia refusing her, by the way? What the hell, Galaxia? I just never understood that. I have no idea how to fix it, so I ended up having to write around it in my own writing, which was really annoying. I don’t see why she and Kirby can’t just fight together after that, even. She sits out for the rest of the fight after getting rejected by the sword. Like you still have a gun, Sirica, you don’t need to move around to use it. OH WAIT, NO YOU DON’T, META KNIGHT TOOK IT. THE ABSOLUTE MADMAN. IT’S BAD, MISOGYNISTIC WRITING!

Oh, I made myself upset. This was supposed to be a positive essay.

Some other miscellaneous ideas I have, that don’t need to be their own paragraphs: What’s with all the one-off characters that seem like they’re going to be important? If the anime was made today, the GSA would probably have a way larger role. If the anime was made today, it probably wouldn’t be episodic (See this video).

I don’t know how to write a conclusion, so here’s a little MS Paint drawing of Sirica instead:

Thanks for reading, and sorry mobile users, if that glitch still exists.

#cant catch me gay thoughts#kirby#kirby right back at ya#hoshi no kaabii#krbay#it takes a lot of effort to write like this i hope u all like it. mwah#also i wrote this very early in the morning so if theres anything wrong with it uh. suck it up

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Force Awakens and fairytales: part two. Prince Lindworm.

This is the second and (probably) last part or my essay “The Force Awakens and Fairytales”. This time I wanted to describe the Norwegian folktale about Prince Lindworm (which can you read HERE) which, in my opinion, is the most accurate summary of Kylo/Ben & Rey relationship. First, I will discuss a theoretical framework and concepts that I will need to conduct proper analysis of the parallels between TFA and “Prince Lindworm”. But don’t get discouraged! Throughout this essay I will continuously get back to the movie.

Some time ago Pablo Hidalgo tweeted that „long time ago in a galaxy far away” should be read as a begenning of a fairy tale. Surely it means more than just a fact that every movie in Star Wars trilogies is similar to popular tales like Snow White or the Beauty and the Beast. A myth or a folktale is, as Karen Armstrong describes it “in some sense is an occurrence that happened once and happens over and over again”, because it takes place inside each of us when we read, adapt and reenact it. “Mythology, just like poetry and music, should open us to a sense of wonder, even in the face of death or a threat of annihilation.”

This notion reminds me of your posts that I see frequently on my dash: those where you described how reylo helps you in dealing with difficulties, how you find yourself in various traits displayed by the characters, how they can voice your feelings and thoughts. Because every fairytale has also a therapeutic aspect, which manifests itself in the said sense of wonder, described by Rudolf Otto as a numinotic experience. Numinosum is an encounter with Mysterium tremendum et fascinans:

Mysterium which is a source for the English word “mystery” has its roots in Greek “mysterion” which originates from “myein” which can be traced in “mustism”, a condition in which a person is deprived of an ability to speak. Mysterium is a superhuman revelation which we experience in silence because it is both tremendum, as you can guess – tremendous, terrible – and fascinans, fascinating. Igen wrote:

“Our religions and psychotherapies offer frames of reference for processing unbearable agonies, and perhaps, also, unbearable joys. At times, art or literature brings the agony-ecstasy of life together in a pinnacle of momentary triumph. Good poems are time pellets, offering places to live emotional transformations over lifetimes. There are moments of processing, pulsations that make life meaningful, as well as mysterious. But I think these aesthetic and religious products gain part of their power from all the moments of breakdown that went into them.”

There is an intimate relationship between the numinosum and trauma, often conceptualized as a rupture in continuity of personal narrative. On the other hand, experiencing the numinosum –through physically inconsequential process of identfication with fairy – tales characters and participation in their adventures as well as struggles – is a factor that could restore unity to individual’s inner world. To paraphrase Kalsched’s claim: a fairytale describes psyche’s self-portrait of its own archaic defensive operations; in other words, it illustrates a psychological process and even though the events from a fairy tale never took place the material world, they take place inside any of us during the lecture. The Force Awakens, just like the story of a dragon or a snake Lindworm is an example of a type of story about a traumatic event, dissociation or a fissure in personality, and the need for internal integration. In this sense the only hero of the story is Prince Lindworm – or Kylo Ren, whose ego (i.e. self) breaks, or is dissociated.

“I’m being torn apart. I want to be free of this pain”

In TFA it happens when Ben Solo symbolically kills his former self and gives himself a new name. He tells Han that “his son is dead” but you know that it is not true and those two identities are alive and at war with themselves. In the story about Prince Lindworm this division is marked in the moment of his birth. Lindworm was one of the pair of twins. Cirlot writes in his book of symbols: “dual nature of twins has two sides, one light and one dark, one giving life and the other bringing death; […] However, the night craves to become the day, evil admires righteousness, life is heading towards death.” This duality often serves a certain narrative purpose and can, for example, be used to avoid the taboo of parricide, like in “Enchanted doe” where one of the brothers kills their mother. In The Force Awakens it is not Ben Solo, Han’s son who murders him, but alien to him Kylo Ren.

It is said in the beginning of the tale that “And this [that they couldn’t have children] often made them both sad, because the Queen wanted a dear little child to play with, and the King wanted an heir to the kingdom”. Then, it is quite possible that the duality of twins is used to illustrate the process in which all unacceptable affects – anger, aggression, defiance – are placed not in the firstborn son but in his shadow, his evil brother. What supports this thesis is the fact that after the happy ending another wedding is prepared but not a word is spoken about Lindworm’s brother. In TFA Kylo Ren represents the same qualities as Lindworm, while Ben Solo is a boy who was born to the light.

This is not the only split visible in the characters of the narratives. The “Prince Lindworm” fairytale belongs to quite popular type which describe the story of monsters which hunt innocent girls, like Bluebeard, the Beauty and The beast and almost all vampire stories.

Their common point is the motive of a malevolent figure, abducting and captivating defenseless woman. What seems most interesting, is that every time a vampire, a sorcerer, or a terrifying creature is both a persecutor and a savior. In the fairy tale of Bluebeard, the protagonist wants to test his wife, but instructs her how she can get out of his jail. Similarly Count Dracula, who in the Coppola’s adaptation allows the woman and the men protecting her to catch him. As Suzy McKee Charnas writes in the "vampire tapestry": the monster is a "predator paralyzed by an unwanted empathy with his prey".

The titular vampire of the story recalls yet another fairy tale, when he accuses the main character that she wants to seduce him. He mocks her, saying: “Unicorn, come lay your head in my lap while the hunters close in. You are a wonder, and for love of wonder I will tame you. You are pursued, but forget your pursuers, rest under my hand till they come and destroy you" That's where the title of this novel came from, and this is what medieval tapestries and paintings depict. Nowadays we think a unicorn is a beautiful, enchanting horse. Once upon a time it belonged to the catalog of wild beasts and in many works of art it is depicted as a dangerous predator, tearing animals and people into pieces.

The ‘Hellsing” manga describes vampires as follows:

It seems that in the depths of his heart the creature from a fairytale wants to be killed. The human part of the monster is suffering because of the terrible fate he was condemned to. It is the girl who impersonates this dissociated, human element of the monster who wants to be defeated and liberated by death.

“You, a scavenger”

Typically, these women are described as virgins or poor peasants – which in the “Prince Lindworm” tale is underlined many times – the narrator often speaks of their bare feet, as in the Snow Queen tales in which Gerda sets out barefoot to the snowy land to save her beloved Kay from Snow Queen. The Lapland shaman says about her: “I can not give her more power than she already has. Can not you see how great she is? You do not see how men and animals are obliged to serve her; How she travels the whole world with bare feet? This power does not come from the magic, it comes from her heart!…”

Still, the bare feet of heroines or their virginity do not symbolize - as we would expect - their innocence. On unicorn tapestries there is often a scene in which a unicorn sleeps in a woman's embrace, and then the hunter's arrows reach him. In this situation, the victim puts her persecutor in a mortal danger. Similarly, Rey is “no one”, lowly scavenger from a desert planet, uncivilized and uneducated. But she is the one who brings the prince to his knees.

At the end of the story, it is said: " No bride was ever so beloved by a King and Queen as this peasant maid from the shepherd’s cottage. There was no end to their love and their kindness towards her: because, by her sense and her calmness and her courage, she had saved their son, Prince Lindworm”. Stories about young men tell about their courage that helped them in the process of becoming a hero; correspondingly, the girl from “Prince Lindworm” is not fearless, but brave when she decides to oppose the hideous snake, or, in case of Rey, to defy someone who might as well be a monster under his mask. When the girl says "Prince Lindworm, slough a skin!" (just like Rey when she wants Kylo to take his helmet off) he replies, " No one has ever dared tell me to do that before". He hissed and showed her teeth, but the girl was not afraid (“you! You are afraid…!”) and persuaded him to do as she commanded. At first we do not know if Lindworm, outraged by her impudence, will not eat her alive, but there is this part of Lindworm which wants to obey and – by revealing his weakness to the girl – make him mortal, easy to hurt. And indeed, "And there was nothing left of the Lindworm but a huge thick mass, most horrible to see. Then the girl seized the whips, dipped them in the lye, and whipped him as hard as ever she could. Next, she bathed him all over in the fresh milk. Lastly, she dragged him on to the bed and put her arms round him. And she fell fast asleep that very moment. "

As it has been said, girl’s compassion is the key to Lindworm's transformation but before this act is completed, "the girl confronts Lindworm with his violence on his own terms." Only after reflecting and recognizing his - and consequently her own - destructiveness and aggression (just the way Rey did during the duel on Starkiller Base), the prince-monster is bathed in milk – which symbolizes the milk of his mother – and can be born anew – so he can lay in the arms of woman. Bettelheim said: "If we do not want to be ruled and - in extreme cases – torn apart by our ambivalences, we must recognize them, deal with them in a constructive manner and reconcile with ourselves and our personalities."

Her grief is nothing more but the mercy shown to a monster by a man in him. It is then that the integration of his "ego" with the numinosum happens. As Anna Freud wrote, "The most pressing task of man is to resurrect what he has annihilated in a defensive reaction, i.e. recreate what has been repressed, return to the previous place what has been displaced what he moved, to return to the old place, and integrate what he dissociated.”

It seems that Ben Solo has a lot work to do! ;)

#Rey#Kylo#kylo ren#kylo x rey#kylo ren x rey#reylo#meta#star wars#Star Wars The Force Awakens#the last jedi#snoke#supreme leader snoke

93 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hyperallergic: The Feminist Avant-Garde, Now More than Ever

Installation view of “WOMAN. FEMINIST AVANT-GARDE of the 1970s” (2017) from the Sammlung Verbund Collection, Mumok, Vienna (photo by Lisa Rasti, © Mumok)

VIENNA — With its array of more than 300 works by 48 artists, the scrupulously researched WOMAN. FEMINIST AVANT-GARDE of the 1970s is a timely and provocative exhibition that argues its points with care, precision, and a magical sense of simultaneity.

Curated by Gabriele Schor, the director of Sammlung Verbund, with Eva Badura-Triska, a curator at the Museum Moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig Wien ( Mumok), where the show opened on May 5th, WOMAN is less a celebration of the varieties of Feminist art than an examination of shared ideas and motivations.

In contrast to WACK! Art and the Feminist Revolution, presented at MoMA PS1 in 2008 — an exhibition that, as I wrote at the time, elucidated “a mutually supportive network that offered both a sense of purpose and a protected emotional space for experiment and play” — WOMAN emphasizes the position of the individual artist as an actor within a range of international movements, both aesthetic and political.

The presentation at Mumok is the seventh stop of a ten-city European tour, from Rome to Brno (unfortunately, there are no plans to bring the show to the US). Its current iteration, however, can be considered a homecoming, given that it is drawn entirely from the corporate collection of the Vienna-based Verbund AG, the largest electric company in Austria.

Schor, as Verbund’s in-house curator, initiated the collection’s focus on 1970s Feminist art. The stereotypical conception of a risk-free corporate collection, however, is immediately exploded by such graphic and aggressive works as Judy Chicago’s photolithograph “Red Flag” (1971), a crotch shot of a hand yanking a glistening, red, phallic tampon from a shadow-cloaked vagina, and Gina Pane’s “The Hot Milk” (1972), a vertical, double-column grid of mostly color photographs documenting a performance in which the artist slices her own back and face with a double-edged razor blade.

In her essay for the exhibition catalogue, Schor writes that Feminist art is “strikingly […] not usually identified as an ‘avant-garde’” despite its political, social, and aesthetic correspondences to previous movements that were historically based on “the discursive paradigm of male artistic genius”:

The inability to perceive the links between ‘feminism’ and ‘avant-garde’ is thus a conspicuous blind spot in both art history and art criticism. […] Yet the feminist art movement’s historic and pioneering achievements in the art of the past four decades is not in dispute. The protagonists of the feminist avant-garde wrote manifestos and pamphlets, established numerous women artists’ associations and journals, articulated a critique of art institutions, organized their own exhibitions, created groundbreaking work in terms of form as well as content, and sought to fuse art with life.

Renate Bertlmann, “Tender Pantomime” (1976), black and white photograph, from a six-part series (© Renate Bertlmann; Sammlung Verbund, Vienna)

The Feminist focus on photography, performance, film, and video was both a formal choice — a turn toward art forms that decisively “fuse art with life” — and a conscious break with the traditional medium-based hierarchies of Western art.

It was also a practical decision, one that obviated the need for a studio, which had become one of the hoariest clichés of “the discursive paradigm of male artistic genius.” Instead, art-making took to the streets, often via inflammatory encounters with an unsuspecting public, recorded on grainy black-and-white photos, Portapak tape, and Super-8 film.

WOMAN makes no attempt to gin up its frequently spartan schema with colorful graphics or digital displays. Instead, it turns the era’s simple, white-walled asceticism to its advantage through abrupt shifts in scale and visual rhythms; a lively interchange of floor sculptures, table vitrines, and pylons of CRT monitors; and framed photos mounted in rows, columns, clusters, and grids, some slightly asymmetrical to deliver a syncopated kick.

The result is a grisaille purism that feels authentic to the period without pretending to take you back in time: the display is resolutely museological throughout, redolent with parallels and correlations as subtle as they are illuminating.

One of the first works you’ll encounter in “Female Sexuality“ — one of the exhibition’s four sections (the other three are “The Beautiful Body,” Role-Plays,” and “Mother, Housewife, Wife”) — is Hannah Wilke’s “Super-T-Art” (1974), a large grid of 20 black-and-white photographs whose title plays on the words “Super Tart,” which she derived from the title of the musical Jesus Christ Superstar (1970). The series of photographs begins with the artist dressed in a Roman-style toga, which she gradually sheds and rewraps into a billowy loincloth, vamping coquettishly, until she ends with her arms raised in mimicry of the Crucifixion.

Uncannily, the French artist ORLAN, in 1974-75, did a similar photo grid, “Occasional Striptease with Trousseau Sheets,” consisting of 18 self-portraits, at first costumed like Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s Saint Teresa, but by the fifteenth shot she’s not dressed at all, with the final image simply the pile of sheets on the floor, as if she had ascended into heaven or melted into the earth.

Both works are intended as comments on Marcel Duchamp’s “The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even” (1915-23), one of the most noteworthy of art history’s countless embodiments of the male gaze. (The show also features Wilke’s notorious 1976 video, “Through the Large Glass,” in which she performs another striptease, this time at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, minimally obscured behind the cracked pane of Duchamp’s masterwork.)

Despite the surface resemblance of these two works, Schor and Badura-Triska afford you enough room to draw your own connections. She could have installed the two photo grids side-by-side, but that would have tilted their intent toward the striptease as an action and not as a social construct. Instead, they face each other from opposite sides of the gallery.

ORLAN’s striptease shoots an arrow from the sacred to the profane, a full unmasking of Bernini’s barely disguised eroticism, while Wilke’s performance is more ambiguous: her transformation from a Roman goddess to a transgendered Christ is too pointed to be unadulterated fun and too joyful for a calculated shot at blasphemy; either way, the apparent transition from paganism to Christianity occurs without the artist placing a value judgment on either.

This relatively small corner of the exhibition is a microcosm of its thematic richness, with images and ideas ricocheting around the installation, some intentionally and others through inference. Hanging close by “Super-T-Art,” Wilke portrays herself in a cowboy hat and round sunglasses in a photo from her “S.O.S. Scarification Object Series” of 1975. The image features her bare torso covered in wads of chewing gum, 13 of which are mounted on nine sheets of paper (to a surprisingly sensuous, jewel-like effect) in a neighboring frame.

But she is also wielding two toy pistols that, in the free-associative interplay encouraged by the installation, make a connection with VALIE EXPORT’s armed and dangerous self-portrait, “Action Paints: Genital Panic” (1969), on the other side of the room. In the photo, EXPORT slumps on a bench while gripping an allegedly real machine gun and exposing herself via her jeans’ cut-out crotch. This in turn relates to Penny Slinger’s photo series of self-portraits as a bride dressed in a mock-wedding cake, which is similarly cut away to reveal the artist’s vagina.

Penny Slinger, “Wedding Invitation –2 (Art is just a piece of Cake)” (1973), black and white photograph (© Penny Slinger. Courtesy Gallery Broadway 1602, New York; Sammlung Verbund, Vienna)

Slinger’s bridal imagery then returns your thoughts to the Wilke/ORLAN riffs on Duchamp, a perspective that broadens your reception of the motif when it reappears in scabrous videos by Ewa Partum and Renate Bertlmann. The bride represents not only a link to a key work of phallocentric Modernism, but also the flash point of society’s idealization and subjugation of women — a balling-up of the warring strains of purity, desire, bondage, and freedom that animate the entire exhibition.

It’s telling that Slinger’s self-portraits greet you at the entrance to the exhibition’s second half (WOMAN covers the third and fourth floors of the museum), and that the image described above, “Wedding Invitation — 2 [Art is Just a Piece of Cake]” (1973), is the second full-page reproduction to appear in the exhibition catalogue, after the Portuguese artist Helena Almeida’s haunting photograph of a hand emerging from a darkened interior and resting on a partly opened casement window.

Almeida’s photo is from series of hands draped over gates, bars, and grates called “Study for Two Spaces,” which she made in 1977, a few years after the fall of Portugal’s four-decade-long authoritarian dictatorship. The hands are neither bound nor free, but are literally on a threshold between the two.

This liminality — the balance between the political and the poetic — stands out as an encapsulation of the work made by these women, who were as ready to turn the world upside down as their mostly male avant-garde predecessors, but were halted at the gate by the social status of their sex. Their only solution was to make their revolution their own way, without help and without precedent. As the Detroit-born artist Suzy Lake said in a symposium sponsored by the museum the day after the opening, “We didn’t know who we were, but who we were not.”

Annegret Soltau, “Selbst” (1975), black and white photograph on barit paper, from a 14-part series (© Annegret Soltau; Sammlung Verbund, Vienna)

The artists’ collective sense of having nothing to lose led them to explore areas that had less to do with personal branding and more to do with personal experience — which, in the aggregate, became an individual entry in the ledger book of universal experience, expressed through the common themes and nested meanings spun throughout the show.

In this regard, Schor and Badura-Triska’s light curatorial touch succeeds in bringing viewer and artwork together in active engagement. Although the show overall is grouped into four categories, its recurring images and subsets of meanings, such as those associated with the Wilke/ORLAN striptease, are woven throughout the exhibition with an almost Pynchonian sense of parallelism and coincidence (an impression underscored by the exhibition’s open-plan design, in which one section subtly informs the next). Objects and actions from both sides of the Atlantic may have been created independently of one another, but come together here as intuited agents of rebellion and resistance.

Suzy Lake’s phrase, “who we were not,” is provocatively reified in two of the exhibition’s most powerfully phallocentric artworks, which the curators have paired on the same wall: Judith Bernstein’s “One Panel Vertical” (1978), one of the artist’s lush Screw Drawings in pitch-black charcoal on thick watercolor paper, and Lynda Benglis’s infamous Artforum ad (actually one of nine pigment prints from a portfolio titled “SELF,” 1970-1976/2012), which depicts the artist brandishing a lifelike, extra-long dildo.

Those two works lampooning male aggression are the center of a genitalia cul-de-sac, with the adjacent walls filled with fantasias on the vagina, with Judy Chicago’s above-mentioned “Red Flag” and VALIE EXPORT’s “Action Paints: Genital Panic” on the left-hand wall, and on the right, tenderly abstracted photographs by Friederike Pezold and sculpturally explicit ones by Suzanne Santoro.

Valie Export, “Tap and Touch Cinema” (1968), video, black and white, sound (© Valie Export/ Bildrecht Wien 2016. Courtesy Galerie Charim, Vienna; Sammlung Verbund, Vienna)

These images lead you away from the overt aggression of the male organ to the covert power of female sexuality. Posters from ORLAN’s performance, “The Artist’s Kiss” (1976), in which she sold French kisses during the FIAC art fair outside the Grand Palais in Paris, an action that got her sacked from a job teaching art in a girls’ school, hang near a monitor playing VALIE EXPORT’s “Tap and Touch Cinema” (1968), a video of her encounter with a leering, hostile crowd as she invites people off the street to fondle her breasts (enclosed inside a box she wears like a halter top) while she times them with a stopwatch.

Less explicit but equally intimate is Sanja Ivekovič’s “Opening at Tommaseo” (1977/2012), a photo series in which the artist, her mouth taped, silently greets visitors to her gallery opening by exchanging touches to their face and hands. A hidden microphone on Ivekovič’s body records her heartbeat, and the resulting audio was played the following day in the exhibition space. As uncomfortably close as these performances may seem, a mental comparison with the lunatic performances of the Viennese Actionists, the all-male band of provocateurs who staged pageants of blood, gore, sex, and death at this same time, attests to their warmth, humor, and relative subtlety.

The struggle between the burgeoning power of women and society’s efforts to repress it — the overarching theme of the show — is expressed mainly through staged photography and films. The artists bind their faces in tape (Renate Eisenegger); fabric (Lydia Schouten, in her savage video, “Sexobject,” 1979/2016); and thread, with its echoes of domesticity (Annegret Soltau); or mash them against a pane of glass, as in works by Katalin Ladik, Birgit Jürgenssen, and Ana Mendieta. It continues to be terribly unnerving to see these photographs of Mendieta’s distorted face with the knowledge of her fall from the 34th-story window of her apartment in New York City’s Greenwich Village, a death for which her husband, Carl Andre, was charged and acquitted.

Ana Mendieta, “Untitled (Glass on Body Imprints)” (1972/1997), C-print, from a six-part series (© The Estate Ana Mendieta. Courtesy Galerie Lelong, New York; Sammlung Verbund, Vienna)

For a number of artists — notably Lynda Benglis, Lorraine O’Grady, Eleanor Antin, Marcella Campagnano, Karin Mack, Martha Rosler, Alexis Hunter, Martha Wilson, Suzy Lake, and Cindy Sherman — one way to control their own narrative was to purposefully dissemble, to retain the power of a secret identity while inhabiting the persona of another, in effect playing the Fool to male authority’s senile Lear. These roles are often defined by men’s expectations, such as Martha Wilson’s impersonations of six character types, from the satin-draped ideal of the Hollywood goddess to the more mundane realms of the housewife, the working girl, the professional, the earth-mother, and the lesbian, while a character like Lorraine O’Grady’s “Mlle Bourgeoise Noir” operates on her own racial and sexual plane.

Cindy Sherman has all but owned costumed self-abnegation for decades, but Wilson and Campagnano were doing it while she was still studying at Buffalo State College, where Lake was a direct influence. The works by Sherman in the exhibition date from those student years, when she was dressing up as various campy characters, male and female, white and black, sometimes cutting them out and pasting them into comic vignettes set against a blank backdrop. Also on hand is the crude but imaginative 16mm stop-motion animation, Doll Clothes (1975), in which she depicts herself as an underwear-clad cutout in dozens of poses, trying on and removing different outfits.

Sherman’s self-portraits, aside from the gender politics implied by the roles she plays, are among the most apolitical work on display, which could also be said of the otherworldly self-portraits and interiors of Francesca Woodman, whose photographs have often been scoured for signals of her early death by suicide at the age of 22. The relatively large selection of prints here, however, underscores not the presence of a death wish but the meticulousness, variety, and imagination of her artistry. The work of these artists does not so much depart from the core idea of a Feminist avant-garde, as serve as a complement to the more expressly political statements, a decidedly female focus pulled into reverse angle.

The irony plaguing this show, of course, is the degree of its relevance. While there have been incremental gains since the 1970s in the institutional recognition of women artists — that is, if you take zero as a baseline — the issues of freedom, equal rights, economic parity, social justice, and personal respect are, if anything, in retreat. The president of the United States, a man whose sexual and racial attitudes were retrograde when they were formed in the ’70s, and who remains mentally and emotionally arrested there, seems hellbent on recreating the decade’s rolling scandals, escalating wars, FBI investigations, special counsels, protest marches, and violence in the streets.

In 1972, Richard M. Nixon’s reelection campaign slogan was “President Nixon. Now more than ever.” That same year, Renate Bertlmann made “The Indiscreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie,” named after the title of Luis Buñuel’s satirical film (also 1972), a work adorned with metal filaments sprouting from the intersection of two linear shapes, a junction implying a hairy rectum.

It’s one of many affronts devised by Bertlmann in a breathtaking array of media: drawing, photography, sculpture, film, installation, and wearable art, including a set of finger gloves made from pacifiers pierced with X-Acto blades — a horrifying concept on every level — transforming her fingers into talons and her hands into lethal weapons (as documented in the 1981 photograph “Knife-Pacifier-Hands”).

Such works were not merely conduits of outrage in the face of repression, injustice, incompetence, and corruption; they were correctives to an aesthetic that referred only to itself, a refocusing of art on the body, and a realignment of concerns from the formal to the social and political. Disdainful of the market, convention, and boundaries, the only goal that really mattered to these insurgent, untamable, experiential artists was to be able to see without filters; everything else followed from there.

WOMAN. FEMINIST AVANT-GARDE of the 1970s continues at Mumok (Museum Moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig Wien, Museumsplatz 1, Vienna) through September 3.

Travel to Vienna and hotel accommodations were provided by Mumok in connection to the opening of the exhibition and its related symposium.

The post The Feminist Avant-Garde, Now More than Ever appeared first on Hyperallergic.

from Hyperallergic http://ift.tt/2pVHZJ7

via IFTTT

0 notes