#i dont know if i want to refer to Budd's species as such. he's just a hell pooch. animal of hell.

Note

randomly saw a post of yours on my dash and came to say i rly like your url. then i saw boe and went :D and now i must say i rly like boe too :]

wah!!! wahhh!!!!! thank you!!!!! 🌺🌹🍀🌸

also i'm always short on words whenever it comes to answering asks like these, but it always makes me smile seeing folks liking Boe. makes me :) <- that. but seriously thank you for liking my bloag name too :) i like it myself too.

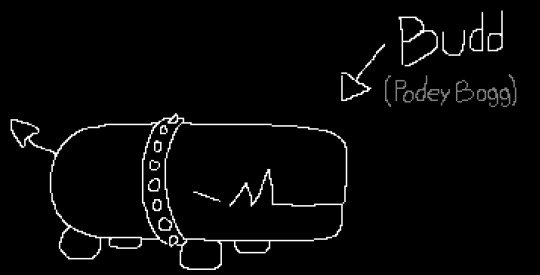

also take a look at Boe's dog okay? okay? his name is Budd okay? this guy

#ask#ackee#boe#boe tai marrow#budd#my characters#my art#i wanted to draw Budd again since i havent done so in a long time... so i did >:]#also podey bogg is just my personal bastardization of ''puppy dog''#i dont know if i want to refer to Budd's species as such. he's just a hell pooch. animal of hell.#he eats trash btw. Budd. not Boe.#Boe probably eats normal things id imagine. whatever limbo's supermarket has. if limbo has one.#also Budd's full name is technically Buddy. but Boe always calls him Budd.#in terms of his size. i imagine him to be the size of a cinderblock. or bigger. basically Boe can pick him up but i think hes a bit weighty#he's also just got one tooth. the opposite of how Boe's missing just one tooth#also i think Budds design is fun in how he's simplistic and easy to draw. whereas Boe is a lot more complex.#i love juxtaposition i think. and themes. its fun i think.#he's also red! you can find more art of him in the budd tag if youd like to see more :) if that feature works correctly still.#you know how tumblrs being recently. agh.#his design became more finalized after i recieved some fanart of him a long while back.... i gotta reblog that again.#anyway :) thank you for enjoying my skeleton and blog name. it does mean a lot despite my small vocabulary :)

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Deleuze and Empiricism

Bruce Baugh, written 1993, read 10/06/2020 - ??

a short article which characterizes Deleuze as an empiricist.

1. intro

Deleuze was an empiricist, but wanted to meet Hegels challenge to empiricism - so rather than arguing all knowledge is generalized from experience, he wants to "search for real conditions of actual experience" - he does not provide foundations for knowledge claims [Hume: Empiricism & Subjectivity, and an article on Hume in Histoire de Ia philosphie (Paris: Hachette, 1972-73) - find this!]

Deleuze takes as his starting point that "there is a difference between real difference and conceptual difference”

this difference is in "the being of the sensible" [difference & repetition]

2. non-conceptual difference

the 'naive' statement:

the concept makes 'repeatable experiences' possible, experiences which are identical to each other

the sensible is 'the actuality of any given experience' - something sensible can never be repeated, so there is always difference between actualisations

the sensible 'as a specific actualization' always falls outside the concept

the concept 'determines the equivalency among actualization', so they are all actualisations of the same concept, while the sensible grounds their difference

[this is a somewhat straightforward statement of particular vs abstract entities, and Deleuze seems to say that abstract entities, as generalities (every red thing is the same 'red', etc.) are never instantiated in particulars, at least not fully; ie. a nominalist view -- although perhaps what is considered significant here is the ordering of the world into the 'different' (each particular different from another) and the 'repeatable' (these particulars all instantiate the same thing) in the first place]

but...

if this were all, the sensible would just be a platform for actualizing the concept - our representations are just determined by the concept [as it is in Sellars, 'theory-laden observation', etc.] (so the sensible isn't noumena, its 'sense-perception'?)

in this case the sensible is 'explained by' the concept, ie. 'a priori conditions of experence', and therefore the a priori that constitutes knowledge

so whatever particularities of a representation aren't covered by a representation are just extrinsic & accidental, as are sensations themselves [don't quite understand this - wouldn't we require an a priori concept to grasp them in the first place?]

baugh offers a justification in parentheses: 'since..' other qualitatively similar sensations can be 'synthesized into a representation' that would be equivalent 'from the standpoint of knowledge' [confusing to me - different things are synthesized into the same representation? are representations repeatable?; I might need to read more about 'representations']

brief aside~

Representation, in the Oxford Companion to Philosophy

‘T.C.’, written 1995, read 10/06/2020

I couldn’t find a good explanation online so I took the opportunity to wipe the dust off of a physical book I had upstairs, using it for the first time in ten years. Trying to read it and type on a screen almost made me sick - perhaps I should have looked harder for an online explnation...

everything that represents is a representation, so... words, sentences, thoughts and pictures are all representations

representations can represent something that doesn't exist (lets say the word 'unicorn') - but all representations nonetheless do represent *something* [this problem isnt resolved in entry]

so we might say: a pictoral representation represents something by resembling it - but this encounters problems. Resemblance is reflexive (everything resembles itself) and symmetric (identical twins resemble each other), but a representation is neither.

Resemblance doesn't guarantee representation: this newspaper does not 'represent' all the other similar issues... [Nelson Goodman argues resemblance is not relevant to repr., Malcom Budd claims he can defend some resemblance theory of pictoral representations...]

Words obv dont resemble the things they represent, but we might see words as representing by linking to mental pictures

but pictures do not represent intrinsically... Wittgenstein gives a fun example: a picture of a man walking uphill could equally be a picture of a man sliding downhill. Nothing about the picture of itself tells us its a picture of the former or the latter.

So we have three choices:

the picture represents by virtue of being interpreted, so representations represent by being interpreted (not resembling something)

mental pictures 'self-interpret' - in this view representations are primitive & unexplanable

representations represent everything they resemble, so one representation represents countless different things - this too makes representations unexplainable

the 'mental pictures' theory also encounters problems, eg. what does a 'prime number' look like to my mind? how could 'we'll go to the beach next sunday' be a pictoral representation?

so there are many sorts of representation which each require their own explanation

recently representations have become very significant in philosophy of mind & there is hope that neuroscience & psychology could uncover a naturalistic explanation of them

back to Baugh~

so a representation isnt anything special - just anything that refers. Its most relevant to knowledge in the form of 'mental representations'... Deleuze seems to endorse a representation-centric theory of knowledge, where we only come to know things through our mental representations of them (I think this is quite common)

so if the naive account holds, similar particulars can be synthesized into a single representation, eg. several bluebells into one mental picture of 'the bluebell' (this being different from an abstract entity, eg. 'bluebells' as a class?)

so there are a few relevant steps: noumena, then I have a sensation of noumena, then I make a mental representation of that sensation (and might synthesize similar sensations together), and I finally know this representation

[I'm reminded of Ayer discussing Hume here, where impressions (ie. sensations?) must be 'brought under concepts' for us to recognize them by associating them with one another -- but this is a slightly different theory, ie. we have direct acquaintence with noumena and make concepts... This is perhaps really similar to some rationalist who stressed the a priori w/r/t sensation, who I'm not aware of - perhaps Kant! -- this would be why Baugh is careful to say 'a priori *conditions of experience*'] (reading this summary is probably much harder than reading Difference & Repetition)

so basically, a representation can be different from the concept (universal), and this is considered something accidental or extrinsic to it, ie. that this bluebell is shorter than the other is just accidental & its still a bluebell, I know it because it is a bluebell to me. The same operation plays out between sensation and representation (I don't really understand how) [its possible he actually means to explain the same thing in two ways, rather than describe two operations at differnet levels, ie. in order to create a representation (which 'leans on' the a priori concept) I have to discard the particulars of the actualized sensation and grasp only what is general to it, ie. I cannot know this bluebell, only what is 'the bluebell' in this bluebell

Baugh describes this view as 'the Kantian challenge to empiricism' (nailed it)

he says there is 'an even greater Hegelian challenge' lurking behind; for Hegel, the particularities of the sensible are not dicarded as accidental, they are instead 'the self-articulation of the Idea', elaborating itself in particular form

for Hegel the concept already contains its particular empirical manifestation, that the two are together the way 'form' and 'content' are in a painting - the form is a 'synthetic organization' of the content

(so the concept is the 'content' and each particular its 'form' - just a particular way of organizing the concept)

Deleuze objects that even if the concept includes empirical content, it cannot already include this actuality (particular)

so for Kant, the empirical is 'what the concept determines would be in a representation if it occured' (so, the flowers of the bluebell would have to always be blue); for Deleuze, the empirical is this actuality itself (the bluebell before me itself), not 'the possibility of existence indicated by the concept' [Baugh writes: see pg 36 of 'Expressionism in Philosophy'; reading this page I dont really understand how its related... Perhaps "substance is once more reduced to the mere possibility of existence, with attributes being nothing but an indication, a sign, of such possible existence." - he's summarizing Spinoza's criticism of Descarte, but we might assume approvingly. Attributes are maybe the 'empirical', the particular - Spinoza argues against treating Substance as a 'genera' of which the attributes are 'species', [ie. where there are attributes 'of' susbtance(?)]; are we to take it that substance is a 'sum of attributes', ie. just empirical reality itself? if so, as Substance empirical reality is undivided, there is no distinction between things in it... (we're back to our point about the ontological equality of all divisions of noumena, ie. the tennis ball, half a tennis ball, etc.; in this case 'attributes' are proper to me, substance has no attributes because there are no distinct 'things' in it, its *just* substance, things are only distinct to me...) - but this seems to be the opposite point than Deleuze's, because for him everything empirical is different, and we make things the same by seeing the concept in them]

Against Hegel we argue that the difference between two performances of Beethoven's 7th Symphony cannot be included in the Idea, because the content (what is performed) is identical but the actual performances differ [is this a good argument? wouldn't the idea/content be 'a performance of the 7th Symphony', and the form be 'each particular performance'?]

for Deleuze the empirical is the difference between each actual performance; this difference makes the repetition of the same work possible

empirical actuality is therefore not possibility -- it is 'the effect of causes' ... 'which are immanent and wholly manifest in the effect through which they are experienced', as Spinoza's God (substance) 'is immanent in his attributes' [now the connection makes sense]

therefore, (here's the juice) "instead of being explicable through the concept ... empirical actuality, 'difference without concept'... [is] expressed in the power belonging to the existent, a sutbbornness of the existent in intuition" [cites Difference & Repetition pg. 23]

difference is a proprety of empirical reality itself, ie. each particular/actualization is different from the others, & it is the concept that organizes them into things which are the same as each other, ie. repeatable entities. each bluebell is already different from the other bluebells, the concept organizes them and declares that they are all bluebells, ie. have some 'being-bluebell' which repeats in them. [I feel like this doesn't overcome our objection to empiricism, ie. what makes this particular the particular? ie., what makes the tennis ball a particular and not half the tennis ball, the ball + some air, etc.? More generally: does it overcome Sellars, 'theory-laden observation', etc.? ie. do we really get the non-foundationalist empiricism promised?]

actually, is Deleuze talking here about noumena or sensation? earlier Baugh says Deleuze "locates difference in the 'being of the sensible'." this might change how we see it, ie. if noumena is undifferentiable stuff - not different or similar in any way - which sensation picks out as 'different stuff', and which are organized into representations which assume similarities between the 'different stuffs'... this makes sense to me.

I think this is the case: "[difference] is first given in sensory consciousness, a receptivity which grasps what comes to thought from 'outside' (DR 74)"

so 'empirical actuality' does NOT = empirical reality/noumena, empirical actuality = the world as grasped by sensation

actualities =/= particular just-so, but where particulars are only existent in sensation

is this a 'third way' between foundationalism and 'theory-ladenness'? that noumena does not yet have particulars, but that my sense-perception organizes it into particulars, but this organization is *not* yet inscribed by the conept (theory, etc) - perhaps instead by my perceptive apparatus, the retina and so on? - the concept inscribes only the representation I make of this sensation. Sensation is a sort of passage between noumena and mental representation, perhaps the organization of the 'hailstones on the window' into associations, and their being 'brought under concepts' is their becoming representations, as Ayer says of Hume?

[calling this empiricism feels a little like splitting hairs by now, esp. if there isnt a foundationalist account of knowledge waiting - I'm not sure that Deleuze did call himself an empiricist, though]

Hegel all of a sudden makes our argument about the tennis ball! or something like it.

Hegel believes that the empirical ['pure actuality'] is 'empty' if it is not organized by the concept; every 'this' is as much a this as any other (ie. tennis ball, half a tennis ball...), so there is only 'indeterminacy'. but he takes this as a criticism of the point, ie. empirical reality cant exist without the concept because it would be empty, a 'negative universal', which cannot have being, is nothing. [This goes for both noumena & sensation; ofc Hegel feels that everything in nature is part of the Idea and so on]

This is where Deleuze disagrees with Hegel. Deleuze "rejects the epistemological model on which Hegel's argument is based", that "whatever does not make a difference to knowledge makes no difference" -- rather "the empirical must be thought even if it cannot be known, at least if knowledge is regarded as knowledge of phenomena" [does this line defeat my earlier conjecture about the empirical not being noumena, ie. the empirical is here not phenomena - but does that mean it is noumena, or simply not yet phenomena?]

for deleuze concepts are possible because of empirical actuality, in two senses:

actualities are "the condition of the application of concepts over different cases & so for universality in general" (different actualties are a platform for universal concepts)

it is the "real condition of experience" (I'm guessing: what we really experience; whatever we can expeirence is empirical actualities)

page 4, btw

NOTE: update 15/06/20 I think the bluebell example I use here may have been uninstructive. For Deleuze the sensible that is difference-in-itself is not objects - it is things like ‘substance’, ‘matter’, ‘energy’ (in their scientific uses); MATTER is difference-in-itself, which we coordinate into repeatable objects via the concept

3. multiplicity and externality

taking a siesta...

3 notes

·

View notes