#i saw someone write a poem on his in a very stylistic fashion

Text

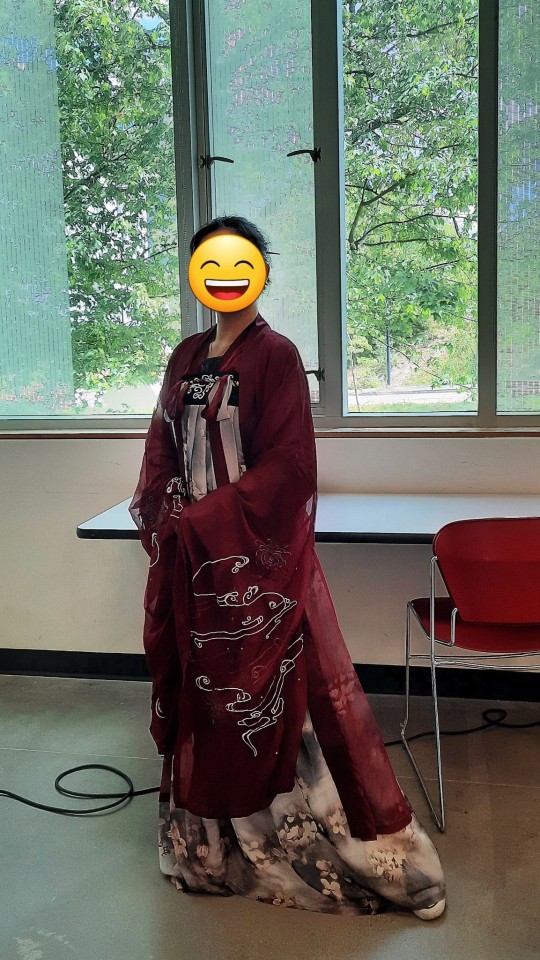

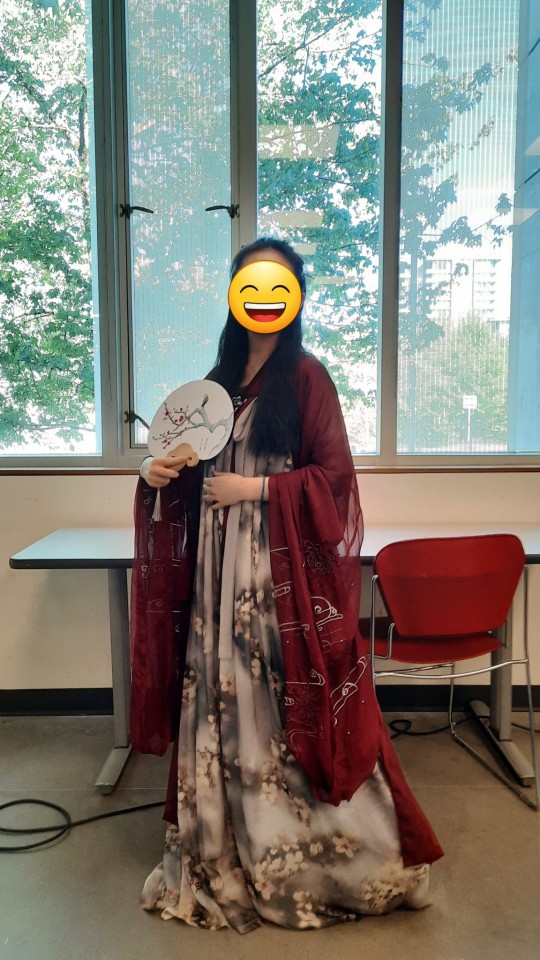

Went to a hanfu tryout and fan painting event!

I tried on this Tang dynasty style hanfu, and although it was a bit too big for me and I could not get used to the sleeves (they kept getting caught on things), it was very fun!

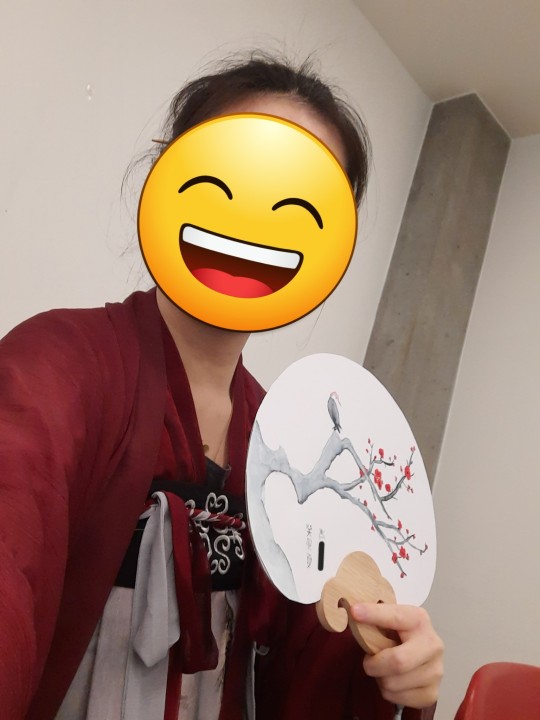

I only wrote the date in the 干支 (ganzhi, 60 year cycle) format and my name (Feng **) because I wanted to write something but had no idea what to write. I was originally going to write in a more cursive style, but then I chickened out, so my writing looks like a little kid's here lmao.

(My phone camera's quality is shit, sorry)

#blu speaks#hanfu#painting#ink painting#looking at the fan now i wish i added more flowers#looks kinda sad lol#not bad for someone who hasn't drawn or painted in years though i think#also everyone else's fans were really good!#i saw someone write a poem on his in a very stylistic fashion#it looked so cool

177 notes

·

View notes

Text

Overcoming Composer’s Block for Young Composers

Alright this is probably gonna be a long one but I figured if I post some advice to other young composers, (and honestly, a lot of this applies to artists in general to some capacity) I’ll be more compelled to follow it myself.

Composer’s block is a bitch. It can make you feel completely inadequate, no matter how much successful music you’ve composed in the past, and it can throw you into a cycle of being overly critical of the things you do write. This usually just makes it worse.

In this post I’m going to address the root causes of different kinds of composer’s block and how to get to the bottom of it, as well as some tips and tricks for how to get your creativity flowing again.

Usually, composer’s block is really just you making excuses about why the things you’re writing won’t work, or why you can’t use them. Unnecessary filters, if you will. I’m literally still in high school, so the most common source for me is varying kinds of imposter syndrome. First let’s break down what imposter syndrome can look like:

It almost always comes down to the phrase: “I’m not a real composer, because....”

1) “Because I don’t even [insert some qualification you think you should have to be a real composer]”

Maybe it’s that you can’t actually play the instrument you’re writing for as well as you feel you should, or that you don’t play it at all. Maybe it’s because you feel like all your music sounds the same. Maybe it’s because you don’t compose using the method that you think “real composers” use. (Ex: you think “real composers” should just compose using a pencil and paper or by sitting with their instrument, whereas you have trouble getting anything that sounds good when you’re not using a notation software to create your music.)

I can guarantee that there’s a very accomplished composer somewhere out there that breaks whatever imaginary “rule” you’ve set for yourself. Even if you don’t know it. Even the most successful composers likely don’t always feel like “real” composers either, and everyone has a different process and style. That’s the thing. No one is a “real” composer because there’s no such thing as “real” and “fake” composers. There’s no magical secret or enlightenment that suddenly makes you successful and worthy of being taken seriously. This applies to every artist. You just kinda have to make your way up the food chain by just... creating as much stuff as possible, seeking out opportunities even when you don’t think you’re worthy or “good enough” for them (we’ll get to that in a minute) and persevering. People may have more experience and musical knowledge than you, sure, but there’s always someone out there that has more experience than them, too. And as far as the actual process of creating music, no one, not even the best composer, always feels like they know what they’re doing any more than you do. Everyone is an “imposter” because if everyone knew some universal secret to becoming a “real” composer, everyone’s music would sound the same. Remembering this usually helps me to realize that these “filters” I put my creative process through aren’t helpful and that I’m holding myself back.

2) “Because people are overestimating my abilities as a composer. I don’t deserve this [insert position/task you’ve been given] and I’m going to let people down and they’ll see that I was fake all along”

There’s a reason you’ve been given this position. Think of what that reason is. Chances are you’ll immediately want to find an excuse to discredit it: “Well they heard my best piece but I could never write anything that good again,” or “they know I compose but they’ve never actually heard my work. They just assumed I was good and I accidentally oversold myself.” There’s still value in both those reasons, even if some parts of those negative thoughts might be true. If they heard your best piece and thought it was worthy, obviously you’ve proven that you’re capable of writing good music, which means you can do it again. Plus, no successful composer performs the crappy music they threw out. Remember that every composer writes bad music sometimes, you just don’t get to hear it. .

If they’ve never heard your work before but they know you compose music, they are interested in seeing what you will create and likely aren’t expecting you to be perfect anyhow. Someone had enough faith in you to give you this task, and you don’t know whether you’re able to do it unless you try. Let your music speak for itself and you’ll likely be surprised at how it’s received by others. If nothing else, by continuing to create music and step out of your comfort zone, you’re learning. There is a lot of value in that alone. An opportunity where you didn’t quite meet your expectations or those of others, but still learned something, is never a wasted opportunity.

3) “Because I like this music but it’s too simple/cliché/[insert other elitist concept] for real musicians/critics to take seriously”

In this era of modern music, of dissonance, and of new, avant-garde, and frankly, sometimes pretentious music, it’s easy to feel like your style has gone out of fashion already or that you simply can’t compete with the complexity of today’s work. To this, I say screw it. Take it from someone who actually had a critic condescendingly tear apart my first piece to ever be properly performed for being too “traditional”. Throw that rhetoric right in the trash where it belongs. Musical styles and concepts go in and out of fashion the same way clothes do. Remember that the style of an era is defined by the music written in that era, and NOT the other way around. Are you writing music? Do you exist currently in what we consider to be the modern era? Congratulations, you’re writing modern music. I know, I know, you’re all saying: “Okay sure, Emily, but the industry doesn’t think that way, and my having that mindset won’t make people take my music any more seriously.” Here’s a little known fact: the Baroque era’s music usually had a “mood” intended by the composer, contrary to the popular belief that it was purely mathematical. Vivaldi’s Four Seasons were inspired by sonnets and the works are also known as “The Contest Between Harmony and Invention.” It was actually the Classical era that saw this concept go out of fashion, when music was not supposed to mean anything, portray emotion of any sort, or be linked to any form of expression. The idea that music conveyed meaning was scrapped in the classical era, only to be brought back again twofold in the romantic era. All this to say, styles come and go, and YOU are part of the force that dictates those styles.

There was once a brilliant composer whose music was said by critics to be too “old fashioned,” simply a fad that would eventually be forgotten. This composer was Sergei Rachmaninoff, who lived from 1873-1943, around the same time as Scriabin (1871-1915) and Shönberg (1874-1951.) Many people are a little shocked by this juxtaposition, and by the stark difference between the music of the latter two composers and that of Rachmaninoff. People didn’t take him seriously during his career, but now he is hailed as one of the greats. This proves that a composer’s passion shows through their music, no matter whether or not it conforms to the stylistic norms of the era, and that complexity and novelty for their own sake don’t mean anything if the integrity of the composer/music are sacrificed to achieve those things.

Now that we’ve discussed some of the ways that young composers often sabotage their own work with pre-conceived ideas of how their music should be created, let’s talk about some strategies to get back into the “flow” after having addressed the root of the block. This can be especially stressful if you’re on a time crunch and you’re worried about meeting your deadline.

Get the cake out of the oven before you start decorating it.

That’s to say, don’t sweat the small things like entering lyrics, dynamics and slurs until you’ve at least hashed out an idea for your work. This can even just be a melody line or a chord progression, but it’s always better to work in layers than to just work “horizontally” (”horizontally” meaning making sure each measure is perfect and polished before moving onto the next.) Working horizontally almost ALWAYS disrupts the creative flow, especially if you get yourself on a roll. You can even get away with leaving a couple blank measures here and there if you have point A and you know what you want point C to sound like, but aren’t sure how to get there yet. If you worry too much about point B right away, you might end up sacrificing a really good idea you had for later on in your piece just for the sake of one or two measures. An added benefit to this strategy is that maybe, once you come back to it, your point B (as we’re calling it for the sake of this explanation) will end up morphing into a whole new section of your piece. If you feel like that’s even better and it should replace the idea you were originally making your way to, then at least you know you tried both and liked this idea better.

2. Take what you have apart and put it back together again.

Focus on one aspect and see where you can take that aspect alone. Maybe it’s tapping out your rhythm over and over again, or isolating a single instrument or motif. Maybe it’s reading through your lyrics with different intonation. With lyrics, I find it helps to copy-paste them into a document and take out the “lines” to make it one big paragraph. (Leave any punctuation that would naturally be there anyways, of course.) This can help you bypass the boring and often repetitive rhythm that usually comes with poems in order to discover new and more interesting ways of phrasing things. Often, this approach even makes more sense because you can let the natural rhythm of the words shine through instead of forcing yourself into a rigid pattern.

3. Don’t get “stuck” on one idea.

Sometimes you have a really cool idea in theory but it just doesn’t work out on paper. I’ve been guilty of shoving my cool ideas into my music by whatever means necessary, often sacrificing literally everything else. It never works, trust me. Just because Bach can have a four part stretto and somehow make it perfectly seamless, it doesn’t mean you have to. In fact, as a matter of personal opinion, I think that music should be appreciated for how it sounds first and foremost, and then it should be appreciated for its technical value and craftsmanship. That’s just me, but regardless, being able to let go of ideas that just don’t work is a great skill to have. (It’s harder than it seems, too, especially if you’re an idea/concept-oriented person like me.) Plus, who knows? Maybe this particular piece just isn’t the right place for that awesome idea and you’ll be able to recycle it later.

Finally, stay true to your vision, no matter what. In an industry like this, where even the most well known modern composers are sometimes struggling financially, it’s easy to sell out. However, it’s important to remember that each composer’s unique vision is what makes the musical world so diverse and interesting. If your vision doesn’t fit into today’s mould, be a trailblazer, and never shy away from something you’re excited about because you think people won’t be ready for it. The music people aren’t ready for can often be the most ground-breaking

13 notes

·

View notes