#if you have not studied late 1800s and early 1900s labor history in the US

Text

"How much safer has construction really gotten? Let’s take a look.

Construction used to be incredibly dangerous

By the end of the 19th century, what’s sometimes called the second industrial revolution had made US industry incredibly productive. But it had also made working conditions more dangerous...

One source estimates 25,000 total US workplace fatalities in 1908 (Aldrich 1997). Another 1913 estimate gave 23,000 deaths against 38 million workers. Per capita, this is about 61 deaths per 100,000 workers, roughly 17 times the rate of workplace fatalities we have today...

In a world of dangerous work, construction was one of the most dangerous industries of all. By the 1930s and early 1940s the occupational death rate for all US workers had fallen to around 36-37 per 100,000 workers. At the same time [in the 1930s and early 1940s], the death rate in construction was around 150-200 deaths per 100,000 workers, roughly five times as high... By comparison, the death rate of US troops in Afghanistan in 2010 was about 500 per 100,000 troops. By the mid-20th century, the only industry sector more dangerous than construction was mining, which had a death rate roughly 50% higher than construction.

We see something similar if we look at injuries. In 1958 the rate of disabling injuries in construction was 3 times as high as the manufacturing rate, and almost 5 times as high as the overall worker rate.

Increasing safety

Over the course of the 20th century, construction steadily got safer.

Between 1940 and 2023, the occupational death rate in construction declined from 150-200 per 100,000 workers to 13-15 per 100,000 workers, or more than 90%. Source: US Statistical Abstract, FRED

For ironworkers, the death rate went from around 250-300 per 100,000 workers in the late 1940s to 27 per 100,000 today.

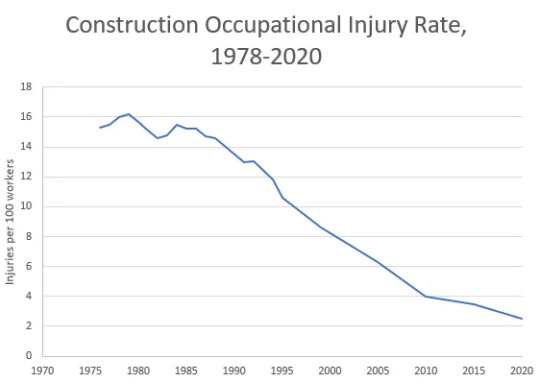

Tracking trends in construction injuries is harder, due to data consistency issues. A death is a death, but what sort of injury counts as “severe,” or “disabling,” or is even worth reporting is likely to change over time. [3] But we seem to see a similar trend there. Looking at BLS Occupational Injuries and Illnesses data, between the 1970s and 2020s the injury rate per 100 workers declined from 15 to 2.5.

Source of safety improvements

Improvements in US construction safety were due to a multitude of factors, and part of a much broader trend of improving workplace safety that took place over the 20th century.

The most significant early step was the passage of workers compensation laws, which compensated workers in the event of an injury, increasing the costs to employers if workers were injured (Aldrich 1997). Prior to workers comp laws, a worker or his family would have to sue his employer for damages and prove negligence in the event of an injury or death. Wisconsin passed the first state workers comp law in 1911, and by 1921 most states had workers compensation programs.

The subsequent rising costs of worker injuries and deaths caused employers to focus more on workplace safety. According to Mark Aldrich, historian and former OSHA economist, “Companies began to guard machines and power sources while machinery makers developed safer designs. Managers began to look for hidden dangers at work, and to require that workers wear hard hats and safety glasses.” Associations and trade journals for safety engineering, such as the American Society of Safety Professionals, began to appear...

In 1934, the Department of Labor established a Division of Labor Standards, which would later become the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), to “promote worker safety and health.” The 1935 National Labor Relations Act (NLRA), which legalized collective bargaining, allowed trade unions to advocate for worker safety.

Following WWII, the scale of government intervention in addressing social problems, including worker safety, dramatically increased.

In addition to OSHA and environmental protection laws, this era also saw the creation of the Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC), the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA), and the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

OSHA in particular dramatically changed the landscape of workplace safety, and is sometimes viewed as “the culmination of 60 or more years of effort towards a safe and hazard-free workplace.”"

-via Construction Physics (Substack newsletter by Brian Potter), 3/9/23

#construction#osha#workplace#workplace safety#workers rights#labor rights#occupational health#nlra#collective bargaining#united states#us history#labor unions#industrial revolution#this is why unions and regulations are so fucking important by the way#if you have not studied late 1800s and early 1900s labor history in the US#you really can't grasp how incredibly dangerous things used to be#and how much proof we have that corporations suck#government regulations

90 notes

·

View notes

Text

My Nitpick Issue with Sherlock in Moriarty the Patriot

By: Peggy Sue Wood | @pswediting

It may surprise some of you to know that I have degrees in book reading and writing. While earning those degrees I studied one specific time period more than the others--that being British Literature from late-17th/18th century through the early 20th century. This is to say that it is a time period I know a little more about than you might think. And early 1900s is probably my favorite period out of that timeline, particularly England under Victoria’s rule.

And, perhaps, because of this strange obsession I have with the period, I presently have a small bone to pick over Moriarty the Patriot.

It’s not the minor inaccuracies of the clothes, nor the adaptation of character designs. It’s not even the adjustment to social tendencies depicted that are more Japanese than British-English of any period thus far either--because those kinds of things happen frequently in adaptations. And it's not Moriarty or his backstory too! Because, again, this is an adaptation, and liberties will be taken to fit the new story (besides, even in the original works by Doyle the man’s backstory was inconsistent).

My issue is with the character of Sherlock and his supposed “deductions.” Well, maybe more accurately it's with the writing of Sherlock.

You see, Sherlock is almost always introduced the same way in an adaptation. He makes a judgment about someone (usually about Watson or the Watson stand-in) and then proves it using his observational skills. This introduction is important because it clarifies that the world of the characters is one based on where common sense and science not only work but make sense. His deductions are logical and based on some semblance of rationality. Here is an excerpt from the original novel:

“I knew you came from Afghanistan. From long habit the train of thoughts ran so swiftly through my mind, that I arrived at the conclusion without being conscious of intermediate steps. There were such steps, however. The train of reasoning ran, `Here is a gentleman of a medical type, but with the air of a military man. Clearly an army doctor, then. He has just come from the tropics, for his face is dark, and that is not the natural tint of his skin, for his wrists are fair. He has undergone hardship and sickness, as his haggard face says clearly. His left arm has been injured. He holds it in a stiff and unnatural manner. Where in the tropics could an English army doctor have seen much hardship and got his arm wounded? Clearly in Afghanistan.'

How does this prove we are in a world where common sense and logic works? Well, because he didn’t pull any of these deductions from thin air. He just used his eyes and common knowledge to make a quick judgment.

In the example above, everything that Sherlock assumes is true and based on reasonable assumptions about the time period and about what he can observe of the person before him.

The tan of Watson’s skin is something he notes because London is usually dark and wet around this season, so you’re unlikely to get a tan. The way the man walks and stands is also a thing he can observe, and fresh military men walk very differently from the average citizen or gentleman. These two observations, coupled with noticeable injury and limp could lead one to think that maybe he has just come back from the current war (the First Anglo-Afghan War). Of course, maybe he wasn’t injured in the war at all--maybe something else happened; however, you can make a pretty good guess that an abled bodied soldier would not be home and looking for a room in the middle of war-times if something hadn’t happened to him on the battlefield.

My point is that all of Sherlock’s deductions come from observing details, paying attention to the basics of the world (such as the ongoing war or understanding rigor mortis), and using your senses. Sure, there may be a few things the average person doesn’t know that Sherlock does, but that’s because Sherlock has studied different things and to a more serious degree. The level of understanding is different, but not impossible to achieve in one’s own time or effort. And, as another note, Sherlock is not perfectly observant all of the time. There are plenty of examples of him needing to take breaks, of him closing his eyes to block out distractions so he can better focus on what someone is saying, and of him smoking to zone out for a bit so that he can come back to a problem with fresh eyes at a later time.

It’s absolutely vital to Sherlock’s character, and the original story, that all of the deductions are based on the “possible,” which is why the introduction of Sherlock in Episode 6 of this adaptation immediately irritated me. Here is the scene:

Side note: I’m sorry it’s shown as a poorly made gif--I literally could not find a copy of the clip with English subtitles on YouTube so I could not include it as a video. If you want to look at it in the episode itself, it starts at about the 13:00 minute mark. EPISODE LINK)

Here is what bothers me so much. Why would a mathematician be checking to see if the staircase on a ship fits the golden ratio? More importantly, why would that in any way matter to Moriarty as a character? Based on what we’ve seen so far of this character, and we’ve had 6 and 1/2 episodes to define him so far, none of Sherlock’s statement makes sense here.

Like, at all. (And I know that this also happens in the manga--doesn’t make sense there either.)

You know what would make sense though? For the time period and the character development we’ve seen of Moriarty thus far? A pause to consider-- and maybe even compare--staircases on the ship between the main steps for passengers and the steps for commoners or staff.

Why would that make sense? Oh, thank you so much for asking. Time to get real nerdy here for a minute:

Class issues were a serious problem in Victorian England (as they are now, though in a different way). These issues were not necessarily the same as depicted in the show but it was still consistently present throughout the society as a whole. (A good, short read on the subject can be found here for those of you interested: Social Life in Victorian England.)

One way that this issue came out was in the very architecture of homes. In Victorian England, nobleman homes and estates were built with main staircases, where the residents and guests walked, and servent staircases, where the staff and other temporary employees walked. The difference in these stairs was huge, as the servant staircases were basically death traps.

In the late 1800s, a mathematician (and architect) named Peter Nickolson figured out the exact measurements that would generally ensure a comfortable and easy walk upstairs:

BTW: Here is a great video on the subject and how they were death traps: Staircases in Victorian England

However, Nickolson’s math and designs were not used regularly in the design of houses for years to come.

By the setting of the story, and given Moriarty’s interest in maths, his understanding of class issues, and beyond--this kind of knowledge would make far more sense than searching for the golden ratio in a man-made set of stairs.

Moreover, the golden ratio is generally interesting to mathematicians (to my understanding) because it can be seen in nature frequently. It is a pattern found everywhere, from the way that petals grow on flowers, to how seashells form, to freaking hurricane formations! So why on Earth would Moriarty be interested in an architect's choice to use such a ration when planning a staircase?

He wouldn’t, I believe. Nor would Sherlock generally be able to make that assumption based on his time gazing at the staircase, distance from said staircase, nor angle.

So what can he deduce, if not that? Well, he may be able to deduce that Moriarty is a nobleman based on his attire. He may also be able to deduce that the man is a student based on age, as in an earlier episode we were told he’s quite young to be teaching in university and appears close in age to his students. Maybe he’s a student of architecture? But, if he’s a nobleman--as we suspect he is based on his attire--then it's unlikely he works a labor-intensive job or one close to it. So, he must be in academia for academic reasons such as mathematics. Physics during that time, as an academic subject, focused more on lighting, heat, electricity, magnetism, and such. And, Sherlock notes that Moriarty is specifically looking at the stairs, not the lights of the ship.

So, BAM! I’ve deduced Moriarty is a young nobleman who is likely a student of mathematics. Perhaps he’s recently had a lesson on staircases or another algebraic concept that’s caused him to pause with momentary interest.

It makes a heck of a lot more sense than finding a “golden ratio” in a man-planned and man-made staircase... don’t you think? And, maybe, we can even deduce that rather than a student he’s a professor who has just thought up an interesting lesson--though that would be a BIG jump from the data we’ve been provided here.

Deductions that come from major leaps in logic make it seem like Sherlock is doing magic... and he is--because it is magical that people find it impressive or believable. It’s not. And I would argue that the original character would find it insulting based on his comments to Watson regarding being compared to other fictional detectives.

Pay in mind, I have this feeling about several adaptations, so my judgment on Moriarty the Patriot isn’t technically exclusive. It just hit me so hard in my first viewing that I felt I needed to share because generally, this issue of deductions becoming magic rather than stemming from logic doesn’t happen in the first two minutes of meeting Sherlock Holmes.

So... yeah. Thanks for coming to my absurd history/lit lesson through Moriarty the Patriot. I appreciate you sticking with me to the end and hope it was enjoyable.

You can watch the series on Funimation.com right now at: https://www.funimation.com/shows/moriarty-the-patriot

Overall, it’s a pretty good series; although there was a lot more child-murder than I expected...

#Moriarty the Patriot#Yuukoku no Moriarty#funimation#analysis#character analysis#character#sherlock holmes#james moriarty

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

Beyond the Archives: How Remote Projects Benefit OHIO Researchers, Libraries Collections, and Staff

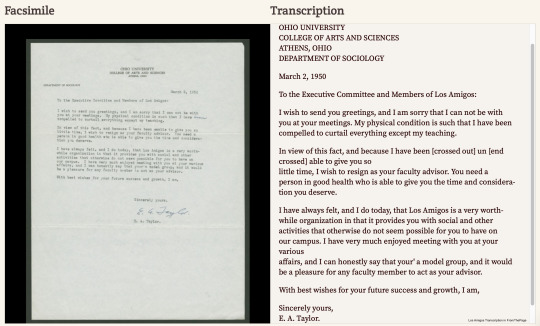

There is an endless amount of work to be done in the digital archives field. When most of the country faced job losses due to the COVID-19 pandemic, online transcription provided Ohio University Libraries was able to pivot to remote work for staff and student workers with tasks that could be accomplished remotely. Contributing to the Libraries’ Digital Archives allowed the libraries to continue contributing to the access and discovery of library collections even when the library itself was closed.

The University Libraries’ Digital Initiatives unit (DI) has long relied on the work of student employees to enhance the digitized primary resources with transcription of cursive materials and correction of auto-recognized printed text. Already accustomed to engaging with the Digital Archives, many of them demonstrated versatility, pivoting to online transcription within a couple of weeks of the initial COVID-19 shut down in March of 2020. Utilizing the web-based software platform designed for collaborative transcription called FromThePage, DI quickly transitioned from using on-site software to working from home. “Before long, participants grew to include not only students within our department but staff and students interested in remote work options throughout the library,” Digital Imaging Specialist and Lab Manager Erin Wilson says.

Without the experience of working with Archives and Special Collections materials — both analog and digital — it might be difficult to fully understand the hidden labor that preserves and makes accessible those contents. “Transcription is vital for accessibility and discoverability of online resources,” Wilson says. “Particularly for handwritten materials, where the text is not easily detected with software.”

University Libraries’ Digital Archives include a range of materials from past and present-day eras, such as the Don Swaim Collection, which includes nearly 900 recorded interviews and radio broadcasts with contemporary authors. “I think some people might assume that archival collections are strictly for old books and documents or that they’re most relevant to someone studying history,” Wilson says.

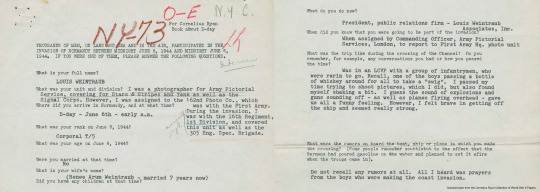

Library Support Specialist Jeff Fulk particularly finds transcribing questionnaires from the Cornelius Ryan Collection of World War II Papers satisfying. The questionnaires bring to life the first-hand accounts of soldiers during World War Two. Transcribing audio collections, such as the author interviews in the Swaim Collection, can be intimidating for him. “I'm more of a visual person,” he says. Luckily, the Libraries offer a variety of transcription projects, allowing transcribers to pick and choose between projects.

As a photographer herself, Library Support Associate Sandy Gekosky appreciated the opportunity to create descriptions for the Peter Goss Photograph Collection, which contains the 1960s work of OHIO alumnus and architectural historian Peter Goss. Although different from transcription, description is another time-consuming hidden labor that some remote library workers have been offered the opportunity to work on. According to Wilson, description “involves tagging and assigning metadata, such as titles and locations, to image files so they can be more easily discovered and understood by users.”

In the Goss collection, Gekosky loves seeing photos of how Athens, her home of 30 years, has changed over time.

“Did you know there was a railroad once that went through Athens?” she asks.

Transcribing since 2019, John Higgins, a Federal Work-Study Student Assistant in the DI unit, has learned just how important transcribers are, especially those who, like Gekosky, take extra time to provide the most accurate transcripts. “It may be easy to go online and look for these documents and sources, but the process by which they get onto the internet is one that is filled with precision, accuracy, awareness, and real passion by the people who do it,” he says. Although many people using the transcripts will not understand the hidden labor that Higgins and others have contributed to the archives, he takes pride in knowing that he took part in documenting history.

Prior to the pandemic, sophomore Kathleen Tuley worked for the Collections Assessment & Access department through the Federal Work-Study program. The amount of work she was able to do onsite in the department decreased with the pandemic; however, she was able to continue her job through the remote transcription projects offered by DI.

Tuley completes the final step in the transcription process. She reviews, or proofreads, completed transcripts from the Ryan Collection, making sure “every word matches perfectly,” she says. As they are completed, the corrected transcripts are then added to the Libraries’ public collections in batches. It’s critical that transcribers provide accurate transcription for future users, which is why Tuley says reviewing is more difficult than it may appear.

Library Support Specialist Kim Brooks began transcribing in the early days of remote working during the COVID-19 pandemic. Brooks says that deciphering handwriting, although atrocious at times, is a satisfying accomplishment. She particularly enjoys transcribing the Board of Trustees minutes from the late 1800s and early 1900s. “They are not at all easy to read,” Brooks says, “So I feel a great sense of accomplishment in learning to decipher the handwritten documents.”

Although at times the material is challenging to work with, transcribers work diligently to improve University Libraries’ archives collections so that students, faculty, and researchers everywhere have access to these accurate, valuable resources. “I found safety and security and stimulating work that produced hundreds and hundreds of digital files online of valuable information for researchers at Ohio University to access in the future wherever they may be,” Gekosky says.

Written by Digital Initiatives Social Media Editor Ellie Roberto, Journalism Strategic Communications major and Marketing minor, expected graduation 2022.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

“In part girls’ extensive reading reflected new possibilities brought about by developments in the American reading public, the publishing industry, and the distribution of reading matter. Printing was one of those industries in nineteenth-century America—like the ginning and the weaving of cotton— that was transformed by technological advances. The result was a substantial increase in the production of books and a much wider distribution of those books, helped along also by the free library movement. High rates of literacy both encouraged and resulted from this increase in the availability of printed materials.

The American Revolution itself, many historians have argued, was galvanized by a public literate enough to read and debate the pamphlets issued by politicized journeymen printers. Women were not well represented among those numbers, though probably many women who could not write could read. In the decades immediately following the Revolution, the literacy rate among women rose dramatically. A study of rural Vermont in 1800 concludes that even away from urban areas ‘‘the proportion of women engaged in lifelong reading and writing had risen to about eighty percent.’’

With the opening of common schools in the nineteenth century, girls were educated the same ways that boys were—unevenly, sometimes at home, sometimes at school, but effectively. By 1880 reading literacy was claimed by 90 percent of the native-born American public and 80 percent of their foreign-born compatriots. The explosion of print in the nineteenth century was enabled by a variety of developments in both technology and distribution. Technological innovations in printing nourished the growth of the antebellum reading public.

The innovations of stereotyping and electrotyping preserved an ‘‘impressment’’ of the type once it had been set so that future editions would not require expensive resetting. The result was that before the Civil War the cost of books dropped to roughly half of their cost in the late eighteenth century. Although at seventy-five cents or more such a price was still too costly for skilled male laborers who earned only a dollar a day, and although inadequacy of lighting in many working-class homes helped to limit the Victorian reading public, a substantial proportion of Americans—those who were coming to constitute the aspiring middle class—were able to gain access to books.

Access to books did not define an American public, but increasingly it defined a class of those who hoped to rise in station. Improvements in printing technology fostered the growth of another literary genre, the periodical, which launched many novels in serialized form in both Britain and the United States. Periodicals in the United States and Britain budded in the early nineteenth century, and a number flowered at midcentury, feeding and fed by the literacy and leisure of Victorian readers. Included among these were a growing selection of magazines targeting special audiences, especially youth.

Youth’s Companion, founded in 1827, mustered the greatest longevity and the highest circulation, and it was joined by the influential St. Nicholas (1873), which amassed a distinguished group of writers. The preeminent magazine for women, Godey’s Ladies Book, achieved a circulation of 150,000 at its prime just before the Civil War. Girls and women provided much of the readership for the general family magazine as well, including Scribner’s, Harper’s Weekly, North American Review, and Century. Periodicals had the advantage of providing regular access to print for a reading-hungry populace and were especially cherished by those far away from lending libraries and those whose economic circumstances forced them to ration their reading.

…The public library movement expanded access to reading material beyond the ranks of the wealthy. Along with the growth of common-school education, libraries provided the institutional underpinning of the reading revolution. As early as the eighteenth century, groups of ambitious private citizens had united to share access to precious books. Later in the century clerks, merchants, and mechanics, too, gathered to form so-called ‘‘social libraries’’ which could be joined by payment of a fee.

It was to one of these libraries which Lois Wells, a resident of Quincy, Illinois, received a three-month subscription for her seventeenth birthday in 1886, probably because there was no public library in her town. The importance of an educated citizenry to a republic encouraged the founding of more free facilities, however. Beginning in Boston, and then expanding outward to New England and on to the Midwest, free libraries aimed to offer to all citizens the opportunity for uplift and self-culture which was previously available only to an elite.

The Boston Public Library opened its doors in 1854, and other cities followed suit in increasing numbers after the Civil War. States supported local efforts by passing legislation which would allow townships to divert public funds to the support of free libraries. A massive government report in 1876 listed 3,682 public libraries, a number which would rise to at least 8,000 by 1900. Access to public libraries was uneven, however, thinning out as one moved west and especially south from New England and the mid-Atlantic.

Taking up the slack between the vogue for reading and its limited supply, Sunday schools enhanced their appeal and ensured the quality of children’s reading matter by acquiring book collections and issuing weekly books to deserving students. When the American Sunday School Union and other religious publishers began issuing prepackaged ‘‘libraries’’ of their own publications in the midcentury (one hundred books for $10), the custom became even more prevalent—until eclipsed by the public-library movement itself.

…The project of self-culture did not regard all reading as equal, of course. The removal of girls from their mothers’ elbows as informal apprentices in housewifery meant a partial surrender of daughters to a national or trans-Atlantic culture. Advice givers subjected it to scrutiny, often discussing the appropriate fare for Victorian girls. In the United States, those standards became the defining standards for genteel culture as a whole.

Richard Gilder, the eminent publisher of Century, outlined the rules for his writers. ‘‘No vulgar slang; no explicit references to sex, or, in more genteel phraseology, to the generative processes; no disrespectful treatment of Christianity; no unhappy endings for any work of fiction.’’ Designed for reading aloud within the family circle, genteel fiction as a whole, but periodical literature in particular, had to pass what was named by poet Edmund Stedman the ‘‘virginibus’’ standard—whether it would be appropriate even for the unmarried daughters of a respectable bourgeois family to listen to or to read.

This reading program had some general precepts. Of course, religious literature of all kinds was favored for study and improvement. The old was better than the new, a rule that encouraged history, and for younger children, myths and legends. Seventy-three years old in 1880, the writer and woman’s rights advocate Elizabeth Oakes Smith suggested a conservative regimen for girls which included history, biography, constitutional and moral philosophy, geography, travel literature, science, and ‘‘the several branches of natural history which open up to the mind the wonders and mysteries of this beautiful world in which we live.’’

An advice giver twenty-five years later explained why myths were appropriate for children’s reading: they were ‘‘interpretive of the beautiful and useful in nature, of the high and noble impulses of the heart, and of the right in human intercourse.’’ The counsel to admire the beautiful and to seek the pure and the true left advice writers conflicted about the most popular genre on the reading lists of girls: the novel. The right novels had power to do much good. The British advice writer Henrietta Keddie recommended ‘‘without fail [Elizabeth Gaskell’s] Cranford, and Miss Austen’s books, to make you a reasonable, kindly woman.’’

The goal of such works was to discipline aspiration, however, for the exemplary woman would be ‘‘satisfied with a very limited amount of canvas on which to figure in the world’s great living tapestry.’’ Elizabeth Oakes Smith implored young girls to avoid the low road and ‘‘most of the fictions of the day,’’ admitting only ‘‘those based on the eras of history, such as the inimitable works of Walter Scott,’’ and the works of Dickens, which ‘‘may deepen our sympathy for the miserable and erring.’’

Another later counselor to young girls, Harriet Paine, in Chats with Girls on Self-Culture (1900) also challenged the appropriateness of realism: ‘‘Girlhood is not the time for any novelist who does not believe that something besides the actual is possible and necessary.’’ She too applauded Sir Walter Scott, who was always ‘‘to be trusted to present a natural world which is nevertheless rosy with the light of romance,’’ and Dickens: ‘‘I never knew a girl who loved Dickens who was not large-hearted.’’

Paine was more inclusive, though: ‘‘There are half a dozen fresh, sweet story-writers girls are always the better for reading,’’ and then she enumerated Louisa May Alcott and a number of British writers, including Dinah Mulock-Craik, Anne Thackeray, and Charlotte Yonge. Much fiction, however, did not grow ‘‘where the rose-tree blooms’’ but instead led young readers ‘‘through mire and dirt,’’ advisers cautioned. Genteel periodicals for youth contained some of the most pointed warnings to youths of both sexes about the dangers of inappropriate reading.

An outburst from St. Nicholas in 1880 warned that a craving for sensational fiction is more insidious, but ‘‘I am not sure that it is not quite as fatal to character as the habitual use of strong drink.’’ The reading of illicit fiction ‘‘weakens the mental grasp, destroys the love of good reading, and the power of sober and rational thinking, takes away all relish from the realities of life, breeds discontent and indolence and selfishness, and makes the one who is addicted to it a weak, frivolous, petulant, miserable being.’’

The power attributed to the vicarious excitement of the emotions remained something of a constant through the nineteenth century. Given such acknowledged dangers, how did girls get access to such books? The question of access played out in a debate over the holdings of public libraries. Librarians made up a new group of elite reformers who aimed to elevate the public intellect through their professional organization, the American Library Association.

In 1881, the ALA attempted to impose uniform censorship on the collections formed for the public good, and got as far as surveying major public libraries and compiling a list of sixteen authors ‘‘whose works are sometimes excluded from public libraries by reason of sensational or immoral qualities.’’ The list included twelve female domestic novelists—such popular writers as E. D. E. N. Southworth and Mary Jane Holmes. It did not go farther. The library ultimately compromised its genteel ambitions with the tastes of the public, and by the turn of the century reliably stocked what its readers wanted to read.”

- Jane H. Hunter, “Reading and the Development of Taste.” in How Young Ladies Became Girls: The Victorian Origins of American Girlhood

#victorian#education#american#censorship#libraries#jane h. hunter#how young ladies became girls#history

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Daniel P. Thurs, The Scientific Method is a Myth, Discover Magazine (October 28, 2015)

It’s probably best to get the bad news out of the way first. The so-called scientific method is a myth. That is not to say that scientists don’t do things that can be described and are unique to their fields of study. But to squeeze a diverse set of practices that span cultural anthropology, paleobotany, and theoretical physics into a handful of steps is an inevitable distortion and, to be blunt, displays a serious poverty of imagination. Easy to grasp, pocket-guide versions of the scientific method usually reduce to critical thinking, checking facts, or letting “nature speak for itself,” none of which is really all that uniquely scientific. If typical formulations were accurate, the only location true science would be taking place in would be grade-school classrooms.

Scratch the surface of the scientific method and the messiness spills out. Even simplistic versions vary from three steps to eleven. Some start with hypothesis, others with observation. Some include imagination. Others confine themselves to facts. Question a simple linear recipe and the real fun begins. A website called Understanding Science offers an “interactive representation” of the scientific method that at first looks familiar. It includes circles labeled “Exploration and Discovery” and “Testing Ideas.” But there are others named “Benefits and Outcomes” and “Community Analysis and Feedback,” both rare birds in the world of the scientific method. To make matters worse, arrows point every which way. Mouse over each circle and you find another flowchart with multiple categories and a tangle of additional arrows.

It’s also telling where invocations of the scientific method usually appear. A broadly conceived method receives virtually no attention in scientific papers or specialized postsecondary scientific training. The more “internal” a discussion — that is, the more insulated from nonscientists —the more likely it is to involve procedures, protocols, or techniques of interest to close colleagues.

Meanwhile, the notion of a heavily abstracted scientific method has pulled public discussion of science into its orbit, like a rhetorical black hole. Educators, scientists, advertisers, popularizers, and journalists have all appealed to it. Its invocation has become routine in debates about topics that draw lay attention, from global warming to intelligent design. Standard formulations of the scientific method are important only insofar as nonscientists believe in them.

The Bright Side

Now for the good news. The scientific method is nothing but a piece of rhetoric. Granted, that may not appear to be good news at first, but it actually is. The scientific method as rhetoric is far more complex, interesting, and revealing than it is as a direct reflection of the ways scientists work. Rhetoric is not just words; rather, “just” words are powerful tools to help shape perception, manage the flow of resources and authority, and make certain kinds of actions or beliefs possible or impossible. That’s particularly true of what Raymond Williams called “keywords.” A list of modern-day keywords include “family,” “race,” “freedom,” and “science.” Such words are familiar, repeated again and again until it seems that everyone must know what they mean. At the same time, scratch their surface, and their meanings become full of messiness, variation, and contradiction.

Sound familiar? Scientific method is a keyword (or phrase) that has helped generations of people make sense of what science was, even if there was no clear agreement about its precise meaning— especially if there was no clear agreement about its precise meaning. The term could roll off the tongue and be met by heads nodding in knowing assent, and yet there could be a different conception within each mind. As long as no one asked too many questions, the flexibility of the term could be a force of cohesion and a tool for inspiring action among groups. A word with too exact a definition is brittle; its use will be limited to specific circumstances. A word too loosely defined will create confusion and appear to say nothing. A word balanced just so between precision and vagueness can change the world.

The Scientific Method, a Historical Perspective

This has been true of the scientific method for some time. As early as 1874, British economist Stanley Jevons (1835–1882) commented in his widely noted Principles of Science, “Physicists speak familiarly of scientific method, but they could not readily describe what they mean by that expression.” Half a century later, sociologist Stuart Rice (1889–1969) attempted an “inductive examination” of the definitions of the scientific method offered in social scientific literature. Ultimately, he complained about its “futility.” “The number of items in such an enumeration,” he wrote, “would be infinitely large.”

And yet the wide variation in possible meanings has made the scientific method a valuable rhetorical resource. Methodological pictures painted by practicing scientists have often been tailored to support their own position and undercut that of their adversaries, even if inconsistency results. As rhetoric, the scientific method has performed at least three functions: it has been a tool of boundary work, a bridge between the scientific and lay worlds, and a brand that represents science itself. It has typically fulfilled all these roles at once, but they also represent a rough chronology of its use. Early in the term’s history, the focus was on enforcing boundaries around scientific ideas and practices. Later, it was used more forcefully to show nonscientists how science could be made relevant. More or less coincidentally, its invocation assuaged any doubts that real science was present.

Timing is a crucial factor in understanding the scientific method. Discussion of the best methodology with which to approach the study of nature goes back to the ancient Greeks. Method also appeared as an important concern for natural philosophers during the Islamic and European Middle Ages, whereas many historians have seen the methodological shifts associated with the Scientific Revolution as crucial to the creation of modern science. Given all that, it’s even more remarkable that “scientific method” was rarely used before the mid-nineteenth century among English speakers, and only grew to widespread public prominence from the late nineteenth to the early twentieth centuries, peaking somewhere between the 1920s and 1940s. In short, the scientific method is a relatively recent invention.

Percent of all magazine articles with the phrase “scientific method” in the title. (Source: Periodicals Content Index)

But it was not alone. Such now-familiar pieces of rhetoric as “science and religion,” “scientist,” and “pseudoscience” grew in prominence over the same period of time. In that sense, “scientific method” was part of what we might call a rhetorical package, a collection of important keywords that helped to make science comprehensible, to clarify its differences with other realms of thought, and to distinguish its devotees from other people. All of this paralleled a shift in popular notions of science from general systematized knowledge during the early 1800s to a special and unique sort of information by the early 1900s. These notions eclipsed habits of talk about the scientific method that opened the door to attestations of the authority of science in contrast with other human activities.

Such labor is the essence of what Thomas Gieryn (b. 1950) has called “boundary-work”— that is, exploiting variations and even apparent contradictions in potential definitions of science to enhance one’s own access to social and material resources while denying such benefits to others. During the late 1800s, the majority of public boundary-work around science was related to the raging debate over biological evolution and the emerging fault line between science and religion. Given that, we might expect the scientific method to have been a prominent weapon for the advocates of evolutionary ideas, such as John Tyndall (1820–1893) or Thomas Henry Huxley (1825–1895). But that wasn’t the case. The notion of a uniquely scientific methodology was still too new and lacked the rhetorical flexibility that made it useful. Instead, the loudest invocations of the scientific method were by those who hoped to limit the reach of science. An author in a magazine called Ladies’ Repository (1868) reflected that “every generation, as it accumulated fresh illustrations of the scientific method, is more and more embarrassed at how to piece them in with that far grander and nobler personal discipline of the soul which hears in every circumstance of life some new word of command from the living God.”

In Public Discourse

Under such conditions, it was no wonder when some people asserted that the “greatest gift of science is the scientific method.”

In his 1932 address to journalists in Washington, D.C., physicist Robert Millikan (1868–1953) informed his audience that the “main thing that the popularization of science can contribute to the progress of the world consists in the spreading of a knowledge of the method of science to the man in the street.” Educators especially promoted the scientific method as a way of bringing science into the classroom. Before the educational section of the American Association for the Advancement of Science in 1910, John Dewey (1859–1952) charged that “science has been taught too much as an accumulation of ready-made material with which students are to be made familiar and not enough as a method of thinking.” In 1947, the 47th Yearbook of the National Society for the Study of Education declared that there “have been few points in educational discussions on which there has been greater agreement than that of the desirability of teaching the scientific method.”

As science became a more powerful force in modern society and culture, thanks in part to invocations of the scientific method, growing numbers sought to take advantage of its prestige. This was especially important for social scientists, who were often seen as scientific pretenders. John B. Watson (1878–1958), the central figure in the behaviorist program, agreed in 1926 that psychology’s methods “must be the methods of science in general.” That same year, the Social Science Research Council retooled one of its subgroups into the Committee on Scientific Method. A conference held under its auspices eventually generated the massive Methods in Social Science. Journalists who looked to social science as a guide during the 1920s and 1930s also turned to the scientific method. In 1928, George Gallup (1901–1984), the founder of the Gallup poll, completed a dissertation at the University of Iowa on “An Objective Method for Determining Reader- Interest.” Two years later, he presented an article called “A Scientific Method for Determining Reader-Interest.” In both cases, he advocated examining newspapers along with readers, noting their reactions.

During the early 1900s, references to scientific medicine, scientific engineering, scientific management, scientific advertising, and scientific motherhood all spread, often justified by adoption of the scientific method. Amid the spread of totalitarianism in the 1930s and 1940s, the ability of the scientific method to sustain a balance between an open and a critical mind foreshadowed a true “science of democracy.” Consumers in a new, advertising-driven marketplace encountered less high-minded examples in books such as Eby’s Complete Scientific Method for Saxophone (1922), Martin Henry Fenton’s Scientific Method of Raising Jumbo Bullfrogs (1932), and Arnold Ehret’s A Scientific Method of Eating Your Way to Health (1922). Eby, for one, never spelled out his complete scientific method. But he didn’t need to. Like the swoosh on a Nike shoe, the scientific method only needed to be displayed on the surface.

Lasting Value

After the middle of the twentieth century, the scientific method continued to be a valuable rhetorical resource, though it also lost some of its luster. Glancing back at the graphs of its rise in public discussion, we can see a fall as it became the subject of increased philosophical criticism. In 1975, Berkeley philosopher Paul Feyerabend (1924–1994) assaulted the very notion of a singular and definable scientific method in his Against Method, suggesting instead that scientists did whatever worked. Educators, too, began to express skepticism. The 1968 edition of Teaching Science in Today’s Secondary Schools lamented that “thousands of young people have memorized the steps” of the scientific method as they appeared in textbooks “and chanted them back to their teachers while probably doubting intuitively their appropriateness.” Such scrutiny cast the scientific method as narrow and brittle, depriving it of its rhetorical utility.

At the same time, the technological products of science, which had begun to invade everyday life, promised a more effective symbol of science and a bridge between the lab and the lay world. Now, instead of new scientific fields, we find biotechnology, information technology, and nanotechnology. Appeal to new technologies available in everything from electronic devices to hair products has also become a staple of advertising. Likewise, modern intellectuals routinely make use of technological metaphors, including allusions to “systems,” “platforms,” “constructions,” or “technologies” as general methods of working. “Technoscience” has achieved widespread popularity among sociologists of science to refer to the intertwined production of abstract knowledge and material devices.

Still, the scientific method did what keywords are supposed to do. It didn’t reflect reality — it helped create it. It helped to define a vision of science that was separate from other kinds of knowledge, justified the value of that science for those left on the outside, and served as a symbol of scientific prestige. It continues to accomplish those things, just not as effectively as it did during its heyday. If we return to a simplistic view, one in which the scientific method really is a recipe for producing scientific knowledge, we lose sight of a huge swath of history and the development of a pivotal touchstone on cultural maps. We deprive ourselves of a richer perspective in favor of one both narrow and contrary to the way things actually are.

2 notes

·

View notes