#it feels like it's only a matter of time before something falls out of goodsir's mouth that makes jopson wish he had his gun back

Text

Harry "If I’m reading right your accent, Mr. Hickey, you grew up in a home where you must have used every part of any meat or fowl your mam could procure." Goodsir vs. Thomas "Everything we ate growing up started with a gun." Jopson

#you're telling me harry goodsir#who said 'it would be good for trade' and 'people in england are good' straight to silna's face#never once did a classism at jopson?#not once???#maybe they never had the opportunity to interact in the show because of the Events#but like#in a rescue scenario#it feels like it's only a matter of time before something falls out of goodsir's mouth that makes jopson wish he had his gun back#the terror#thomas jopson#harry goodsir#anyway if you've seen my jopson/tozer posts you know where this is going

69 notes

·

View notes

Text

Three-Time

“Come, I’ll show you.” His hand extended.

“I don’t care to learn.”

“You just don’t want me to lead.” A quirked eyebrow, an incremental lift of the lips beneath his thick, neat mustache. How his eyes soften imperceptibly from sharpness to sly warmth. Cornelius rises to his feet.

“Once you learn,” Billy continues, “you can lead. Now, put your hand up on my shoulder—there—good. The waltz is a simple dance.”

“Where did you learn, then?”

“Never you mind. Now, this—”

“You’ll tell me one day.”

“Jesus, Cornelius. I may as well tell you now, else you’ll dog me to death about it.”

“Oh, I was just curious.”

“Please. I can see you turning green, ridiculous man. ‘Twas a neighbor girl. Taught me to amuse herself.”

“It’s certainly stuck well.”

“It’s—a nice, neat thing to know. I’d practice when I was alone.” This is true. In a hazy shaft of light in his garret bedroom, stooped so as not to strike his head, he’d sometimes trot a methodical box-step. It was neither the romance nor the grace of the thing, but its order; the mercy of its repetition. One might enter a space outside of time; each turn twin to the one before. It was as though there was always, somewhere, a room in which he might be found waltzing and he only had to step into it to meet himself there. (His mother characterized him as a lonely child, but she was wrong: he was a solitary one.)

“And when you weren’t alone?”

“Jealousy is unbecoming of you, Cornelius. You get a face like a kicked pup. All stung-looking and wide-eyed.”

“I’ll show you a kicked pup—I know a fine long greyhound could use a swift boot to the ribs.”

“Oh, darling. I’m not in the mood. And anyway, there’s no one else now, is there?”

“Is there?”

“As though you’d not trade me for that roustabout marine in a moment.”

“Not a bit, Billy. Truly.” He pauses, and then, his eyes dancing, “I do like a head of curls though.”

“The waltz,” Billy says sharply, sliding his hand down into the shallow tuck of Cornelius’ waist. “I step forward, like so—my left foot. And you, with your right, step back. Good. We move in three-time.”

“We’ve no music.”

“We’ll make the best of it. Three-time.”

———

Cornelius kisses the inside of his thigh, his knee, the freckled hillock of his shoulder, but nearly never his mouth. It’s not a gesture Billy misses until it’s Cornelius who doesn’t do it. Cornelius who talks of making him his bride when he’s hilt-deep in him, Cornelius who promises him wedding rings. It feels like so many coins thrown into a well.

Not that he doesn’t think he means it: but he’s a hard little man, and no matter what he wishes for it comes back to him as an echo, a splash.

Three-time. Their breath falls into three-time when they fuck, and Billy likes to imagine it as a kind of waltz. Parquet floor, heavy velvet curtains tied back with gold cord. A quartet playing. We’ll make do, he’d said, but to tell the truth he misses music terribly. He’d not heard it often but when one dances one should have it. He did not like things done in parts: when one fucks, one should kiss. When one kisses, it should be the upon the lips. And if men are to know each other they should do so wholly; they should be naked together. They should know one another’s bodies so they don’t mistake one another other for beasts. All Billy knows of Cornelius is his neat pink prick, its coppery nest, the luminous, dwarf-like handsomeness of his face. His hand, his boot.

Later, when he’s stripped for his lashing, Billy is astonished by Cornelius’ dense, clustered musculature. He’d thought he was all skin and bone under there, all rib and rope. Belly like a tea saucer. Instead, he’s compactly strong—sleek and rippling and certain, like a dog with a cruel master.

“Shh,” Cornelius hisses now, slowing the neat, hard pistoning of his hips. He’s got his hands spanned over the taut dip of Billy’s waist and now, as though to give teeth to his words, he clenches in with his nails. “Someone’s coming.”

There’s a shuffling step on the ladder, and then here’s Lt. Irving, peering into the dark with eyes smothered hot, like candles just blown out.

———

Lieutenant Irving has his hand on Billy’s knee as he tells him all about Cornelius Hickey, the devious seducer. What he says is not altogether true and it’s not quite false; like all fated things there was a compulsion to it that transcends blame. From the moment they met, Cornelius striking up conversation over a shared cigarette above board one of the fair, early days, it was clear what would happen. Yes, Cornelius had this way of looking at him, a gaze warm and sly and inviting, but Billy—Billy recalls moments of looking back at him the same way, heat in his cheek and his gaze (which he normally kept studiously shuttered) softening. He knew even as he gestured at resisting him that it would happen.

He’d dreamed, in those early days, of standing in a high open window, the wind singing at his knees and nose, tipping forward, forward. Or like this: the thing about waltzing in three-time is that the beat falls an eyelash short of time enough to execute the steps, so between the two partners vibrates this small, bouncing pull and if one will waltz at all one must move in this broken surging beat, even as, to untrained eye, it seems a stately and slow dance. It seems clear who is leading. But the dancers know better.

Not that any of this would matter to Irving. Irving asks what, exactly, they do together; how it works. He starts to sweat, leans in closer. His hand weighs heavy on his knee.

———

Tozer’s many things Billy’s not: muscular in a proto-masculine kind of way, one evolutionary step from pounding his chest in a jungle somewhere; he’s commanding in the grunting, stomping way of a beast too. His attractiveness is of the conventional kind—broad, milk-fed. A whiff of the rustic about him, as though despite his evident vanity one might faintly scent manure in the nooks of his body.

He’s also dumb. It pains Billy to think that that’s what Cornelius wanted all along, somebody lovely and stupid and easily cowed, for as much as he adores him he’d not be any of those things—especially the lattermost. Most infuriating are Tozer’s attempts to fake being the one holding the leash. One should not deceive oneself about the kind of man one is. Like out there alongside the boat, preparing for the walk-out. You’ve just given me permission for a good shove. Idiot. Billy nearly laughs aloud. But then Cornelius gives Tozer that disgusting up-and-down, charting the bulky sullen fact of him as he french inhales. Peacock. He never tried to court Billy so.

False, Billy chastises himself. Only after it was over between them did Cornelius slip that mysterious ring onto his finger, his eyes all dancing.

Later, huddled against one another in a tent beneath one blanket, Cornelius sees the ring around his neck. He lifts it to the light of the guttering candle, turns it in his fingertips. He can feel the scant, damp warmth of Cornelius breath on his lips and it is very nearly a kiss.

“I meant it when I gave you this, you know.”

“What, exactly, did you mean by it?” He makes his voice as glacial as he can manage for the roar of his blood.

“Well, for one thing, I’m sure Sol’d be a terrible dancer.”

“It’s too late for this.” <I>Too late. If you kissed me now you’d taste copper in my teeth.</I>

Cornelius cocks his head, smiles softly, lifts his mouth to Billy’s. A single, chaste glide of the lips.

“Dance with me, Billy,” he says, standing up and extending his hand.”

Billy thinks for a very long time before he drops his gaze to his knees. “Don’t be stupid, Cornelius,” he says. “We haven’t room.”

“We’ll make the best of it.”

Billy stands, stooping so his mouth grazes Cornelius’ hair. He lets Cornelius lead, and is touched he remembers the steps. They waltz a few tight rings, Cornelius humming off-key. Then he kisses him again and leaves the tent.

(In the morning, there’s a new bruise on Tozer’s neck, a plummy, amorphous shadow in the shape of an open mouth.)

———

In the dream they cling together tightly, their bones interlocked like key’s teeth and lock tumblers, and he can’t tell if they are in flagrante or in a mortal struggle or just pressed together against the cold, or maybe they’re just dancing in a crowded room: yes, that’s what they’re doing. They’ve got their quartet at last, their curtains with braided cord. But from the far end of the room comes dark like seeping watercolor, a rolling streaky blackness, and when he wakes it is not darkness at all but pain, pain, pain. A crystalline pinching in his knees and elbows. He goes to see Goodsir.

Rather, he goes to see the man he understands to be Goodsir. This man in their camp is not the awkward, genial stammerer who gave him his physical; not he who enthused over crustaceans with carapaces no man had seen before: he recalls him once pulling him aside to show him, waving one over-sized claw angrily, a crab with a shell the speckled cream and red of some kind of yardbird. Showed <I>him,</I> Billy, because he was there and he was brimming with love for it, this new quick thing caught in a bucket. (Billy had given him a tight smile and walked on, Irving’s bedding wadded and wet from the wash on his hip.)

Now with a gaze immeasurably indifferent, and a queer trace of pleasure in his voice, Goodsir delineates to Billy the agonies of his imminent death. Billy doesn’t mind. He deserves it because he did not love the crab, perhaps, or because he did love and choose badly, or because—his brain is fevered, his thoughts like: he can think of nothing. He stares emptily past the good doctor. He has never been vain, exactly (though he was once—it feels a lifetime ago—possessed of a certain fastidiousness that might be mistaken for vanity) but now he wonders if he looks as wretched as he feels. Carved, hollow: once he saw an egret’s ribcage predators and the wind had picked clean. For a moment he mouths at something, but then Cornelius is there.

He thinks of nothing as he gazes down at him, his eyes the color of surf, except perhaps—how lovely you are, little and glittering. And, I wish I’d kept you. Easy to say, now that Irving’s gone, one hopes, to his gracious and beloved maker. His bones turned up like broken china beneath the shale. Billy wonders, not for the first time if it wasn’t, in part, an act of vengeance—did Hickey care enough for such a thing? Then: Hickey’s eyes swim as he peers up at him, like, like: it feels like—dizzy, he feels, as Hickey disappears, for just a moment; when he returns it is with a knife neat through his ribs—what was it he felt when he looked in his swimming eyes that last time? It was pain, it was love, it was pain.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

How Light Carries on (Endlessly)

What waits for Harry Goodsir, after?

(for @kaserl and for the @theterrorbingo square “Henry Goodsir” | pairing: Goodsir/MacDonald | word count: 1219 plus endnote | rating: T | warnings: mild angst, some death and gore discussion)

+

Whiteness, clear and cold.

The heavy curve of a whale’s bone, the delicate filigree of a seashell, a feather fluttering in a sea-breeze.

All white and quiet. Clean.

Harry blinked, the whiteness sparkling in his eyes, falling away like glittering stars, leaving darkness behind. Harry began to worry. (Harry realized it was perhaps a little late to worry, all things considered.)

The darkness stretched out before him. Harry could practically feel his pupils widening, trying to catch any light and finding none. He spun, the darkness around him in all directions. His heart beat quickly in this chest, but just as he began to feel the panic come, he saw a glimmer off in the distance.

He took a step toward this spark of brightness, and recognized the sensation of sand shifting under his feet, that uneven feeling he remembered from when he had been just a young boy, playing on the beach with his siblings, searching for crabs and clams and little living things. The air was heavy with salt, he realized, even now. The sea, the sea.

Harry realized that there were rock walls around him, dimly lit by a cold light ahead. As he picked his way across the sandy ground, the glow filtered in brighter – a crisp white moonlight coming from the end of this cave in which he had found himself.

There was an end, then, before him: some new world that Goodsir would have to face. He began to hear the sound of waves lapping at the shore, somewhere ahead in the darkness, and, spaced among them, the footsteps of someone else, coming closer.

Goodsir sped up. Whoever it was, he’d meet them head on.

But the figure that came out of the darkness was not the threat for which Goodsir had braced himself.

“Oh lord, Goodsir, is it really you?”

That voice. He knew that voice.

Goodsir hurried forward into the faint light, his heart feeling tender in his ribcage.

Dr. Alexander MacDonald stood there, no wound in his chest, no blood on his lips, just his brows tilted in concern and warm kindness in his eyes. Whatever Goodsir had expected after what had happened, after what Goodsir himself had done – darkness, nothingness, atoms, stars, perhaps even (he had worried, idly) some punishment for his failures, some hellish inferno – this had never crossed his mind.

That he’d see MacDonald again.

“Goodsir, are you alright?”

Goodsir felt a very distant memory return to him, and let the old words trip off his tongue, a bit brittle, “I wish you’d call me Harry.”

Dr. MacDonald smiled. Goodsir prepared himself to hear some unfortunate little echo of the past in response, some weary variation of the title ‘doctor’ that Goodsir hadn’t earned, had lost the right to claim – if he’d ever had that right. But MacDonald merely tilted his head, catching Goodsir’s gaze, and took a step closer. “Of course,” MacDonald said, warm and firm and caring, “Of course, Harry.”

And Goodsir felt himself crumble.

It was like Morfin’s death, but worse, somehow. Then, Goodsir had struggled to breathe. He had wanted to curl into the furs on which he slept and perhaps never leave, whatever would end the horrible, uncontrollable shaking, whatever would take away the shock of the gunshot from his memory. Now, the heavy breathing, the sobs, the trembling – they had all returned ten-fold, and there was no tent to which Goodsir could escape. No place to hide this collapse from the eyes of the men who needed Goodsir to be their doctor, their bulwark against the injuries and illnesses that preyed on them like wolves.

The pressure Goodsir had felt, to shield the men from the ravages of the lead in their food and from the creature and from Hickey and from all of it – so much he’d carried, and he’d been forced to cast it all away in ruin nonetheless. It was that same pressure he’d once felt to impress Dr. MacDonald, but when the consequences were not his own scientific pride but the very lives of the men, it had crushed him.

It crushed him now.

Goodsir turned away in a last effort to hide this failure from MacDonald.

But it was, of course, too late. Goodsir felt a tentative hand on his arm, and had no strength to resist when MacDonald turned him around. The doctor certainly noticed how Goodsir shook, but Goodsir could not bring himself to look up and confirm that MacDonald could see his weakness.

It was because of this, because his eyes were fixed on the sea of darkness below, that Goodsir did not at first realize that MacDonald had not stepped away, had not dropped the hand that had cradled his arm. In fact, MacDonald’s thumb began to circle gently, warm and slow, pressing faint but present caresses through the fabric of Goodsir’s shirt. Goodsir’s breath slowed, keeping time with these circles. When Goodsir’s shudders had eased, MacDonald spoke.

“Oh Harry, I’m so sorry. This should never have happened. You didn’t deserve this, to have to shoulder this burden alone. And yet you’ve cared for them so well, I know you have.”

Goodsir knew that Dr. MacDonald didn’t know much of what had happened, didn’t know what, exactly, Goodsir had done, the depths to which he’d descended during those worst moments in Hickey’s camp.

But it didn’t seem to matter so much, anymore. Not when the darkness around him felt almost safe again. When the slow wash of the waves outside promised life, continuing on again. When MacDonald stood before him, flesh and blood and breath again.

Goodsir struggled to find words, but he reached out a hand – though it trembled – and placed it hesitantly over MacDonald’s other hand, which lay palm up between them, an offering. With a slow movement of his own, MacDonald shifted forward so that Goodsir’s hand now lay over MacDonald’s bare arm, the pulse at his wrist strong and steady under Goodsir’s fingers.

Goodsir gazed down at this touch, and realized he could feel not only MacDonald’s heartbeat but his own. His own pulse thrummed through his own wrist, whole and untorn and pressed warmly against MacDonald’s forearm, where the doctor’s shirtsleeves had been rolled up to his elbows.

Breathing in sharply, Goodsir looked up once again, and found that MacDonald was watching him closely, that same patient look in his eyes. There was no judgement there, only warmth and maybe something that looked like pride.

They stood so close together now, with only a hand-space between them. Goodsir allowed himself, at last, to lean into the strength of MacDonald’s hand on his arm, which quickly became an embrace as MacDonald tucked Harry up against him, placing an arm around him and holding him close.

They breathed, together. Harry’s head to rested against MacDonald’s shoulder and he reveled in the quiet, in the dark, in the steady sound of MacDonald’s heartbeat against his ear.

Finally, Harry stepped back just a fraction, to look up at Dr. MacDonald’s face as he spoke at last, “Thank you, doctor.”

MacDonald continued to cradle his hands, the slow motion of his fingers gentle and calming over Harry’s palms. “I wish you’d call me Alex,” he said with a sudden, sly grin.

And somehow, Harry laughed.

It felt alright, laughing.

+

Source notes: Title from “Saturn” by Sleeping at Last, from @kaserl’s brilliant, massive Terror-playlist. Thank you for your music, your incredible Goodsir thoughts, and for watching The Terror in the first place!

This fic will eventually be posted to ao3, but there’s a bit more I’d like to add to it first (oh, terror-bingo deadlines…) But with this fic I’ve managed to fill out my first row, which I’m calling a win, given how late I signed up, and how late I’ve come into the Terror fandom in the first place. Thanks to everyone for their support and encouragement!

#theterrorbingo#harry goodsir#alexander macdonald#the terror#the terror amc#terrorposting#hope you enjoy!!

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Terror Notes: “Go For Broke”

well… I guess I’m really doing this! Some proper, bullet-pointed notes for each episode of The Terror, starting with ep 1: Go For Broke!

I wrote these out last night (and edited them this morning to make them readable - you’re welcome!) so I hope that y’all enjoy my thoughts and assorted nonsense! I tried to save my comments for points I actually wanted to make because I feel like they bring something to the table but I still ended up writing A Lot lol

I love that Crozier couldn’t even be bothered to be present in welcoming Sir John and Fitzjames onto Terror, making Little and Hodgson do it by themselves. One could argue that he had important captain-y things to be doing at that time or something but I’m not 100% sure that wasn’t the case.

idk if it’s just the angle, but I paused the episode just as the shot of the officer’s mess is coming in from above and Hodgson’s hands make me so uncomfortable. They look so bone-y and weird. (Just what you came here for, I know. Hand commentary.)

Cannot tell you how uncomfortable it is, after many rewatches, to listen to Fitzjames recounting in a casual, lighthearted manner 1) shooting people 2) people catching fire (and burning to death), and 3) their burning flesh smelling “like roast duck” (so, like something edible) and it’s even more uncomfortable to have the closeup be on Hodgson’s face as he laughs at the ‘roast duck’ comparison.

On a lighter note: I love that Fitzjames felt the need to remind everyone what size cherries are by illustrating it with his fingers. In case they forgot, I guess? As someone who occasionally speaks unnecessarily with my hands, big mood tbh.

I LOVE it when Fitzjames gives Little that affirmative tap on the arm after he compares Fitzjames’s injury to Lord Nelson’s. My friend Eli and I refer to it as The Fitzjames Arm Tap. I would like a Fitzjames Arm Tap, pretty please.

God, Sir John loudly setting his hands on the table to try to dispel the tension from the ‘birdshit island’ debacle as he attempts to change the subject is so funny. I’m gonna stop just pointing out things I find funny soon, I swear, but I just cannot handle this scene.

Between Hodgson looking horrifically embarrassed by Crozier’s outburst at Fitzjames and Little looking nervous when Crozier shoots him a look as Sir John says that there’s no reason to be concerned about the ice, it really does seem that they were having to ‘manage’ him even back in ep 1 when his alcoholism wasn’t completely out of hand.

Personal sidenote about this: My Pop-pop is often rude to workers in stores and restaurants (he doesn’t drink thank goodness but he has Alzheimer’s coming on which has worsened his temper) so I very much understand the feeling of being on-edge that an outburst is going to occur and trying to deal with the fallout when it does. Just going by my own experience, I can imagine Little apologizing to Fitzjames for Crozier’s rudeness as soon as they were out of Crozier’s earshot (not that anything Little could say would heal the deep psychological wound that Crozier created but hey, it’s something).

The way that Sir John brushes aside Dr. MacDonald’s and Crozier’s concerns about moving Young when he’s in such bad shape never fails to upset me but also ~foreshadowing for hauling the ill on boats oooohhh~

I said I was done pointing out random things that amuse me but the speed and agility with which Des Voeux pops out of the hatch and onto the deck after Orren falls into the water is just so funny. I could watch that two second clip on repeat all day. Might gif it so I actually can.

Is this a good time to point out that there’s also a scene in Moby-Dick where someone falls from high up on a mast and drowns? It’s in a chapter all about bad omens experienced by the crew of the Pequod and The Terror definitely has some similar vibes going on with the sun dogs displayed in the establishing shot of Erebus in that scene and David Young, a “warning of things to come,” on his way over.

The second(?) time I watched the part where Young tells Stanley that he didn’t think anything of getting headaches since he’s always gotten them, I had this thought pass through my head that was like “oh god, I had chronic migraines for years so I’d never have known if I had lead poisoning either!” but then I realized that this probably was not a relevant concern I should have.

Not sure I have any deep commentary on this but as Gore informs Sir John and Fitzjames about the blocked propeller, he’s standing in the same spot, in the same room as Goodsir will stand next episode to tell them about his death.

Also regarding this scene, I love how Gore waits for Fitzjames to give him the go-ahead to leave before actually going. I know that Fitzjames is his superior officer too but, since Sir John already dismissed him, it seems like waiting for Fitzjames’s approval isn’t really necessary, yet a nice thing to do. Perhaps this is a legitimate formality, but something similar happens later in this episode in the command meeting when Crozier asks Gore how many sun dogs he’s seen; he looks to Fitzjames and waits for his nod before answering Crozier. He doesn’t look to Sir John, he looks to Fitzjames. I know that we know essentially nothing about Gore but like.. underrated ship???? Just saying…

Ten nights ago, I was unable to get to sleep for at least an hour because I started thinking about David Young’s saying “I want to go to my grave as I am” and, of course, that ultimately doesn’t happen for him but also, this, like all things about him, is a “warning of things to come.” I’m pretty sure that no one else was properly buried until, arguably, Fitzjames and ironically, that was explicitly not what he wanted done with his body (and, since his grave was later looted by Hickey, similar to the way that Young’s autopsy ultimately achieved nothing, it didn’t really matter anyway).

I know that this happened exactly ten days ago because I forced myself to wake up and write it down in my notes app, lest I forget, which only prolonged my sleeplessness. I suffer for my analysis.

Ah yesssss Tozer’s lesbian haircut. We love it! Why does my hair not look like that when I take a hat off? I’d like to file a complaint.

Was just thinking the other day about how Hartnell being the one to notice that there was something up with the ice in ep 1 is followed up on with Blanky complimenting Hartnell’s ability to read the ice to Crozier in ep 7. I wonder if Blanky ever gave him like. ice-reading lessons after becoming aware of his interest and natural talent at it in ep 1? That makes me happy to think about.

The two people who we’re shown awoken by Young’s screaming are Sgt. Bryant and Morfin and like. Do I even have to explain why that’s an Oof?

The way that Goodsir hesitates before knocking on Stanley’s door and Stanley irritatedly closing his book before answering the knock in an exasperated voice would be comedic in any other context. If I’m being honest, it still makes me laugh. As does Stanley’s “As if that weren’t plain.”

I’ve pointed this out before but mmmmm... that shot of Stanley in profile with the open candle flame in the background… the foreshadowing in this ep is thicker than the smoke at… Oh alright, I’ll stop.

God, the autopsy/dive scene…. Collins being lowered down and entering the water paralleled with Goodsir’s initial cutting into Young’s corpse, the breaking up of the ice paralleled with the cutting of the bone-saw. But most significant to me is the parallel of what is seen/not seen and the long-term effect that this has. Collins sees Orren’s corpse (and then presumably never tells anyone about it), reinforcing his guilt over Orren’s death, the beginning of his mental health decline. Goodsir doesn’t see the cause of Young’s death in his autopsy and this not knowing about the lead poisoning until it’s too late to do anything about it is the cause of many of Goodsir’s later problems as well. And, to finish it all off, both the autopsy and Collins’ dive were ultimately for nothing (considering a spinning propeller is useless when your ships are frozen in).

Crozier and Blanky’s simultaneous face journeys as Sir John rambles on about how there’s nothing to worry about and they’ll find the passage any day now are truly legendary.

I wrote some pretty extensive tags on this already but man… Crozier’s comment about how not all of Sir John’s men returned from one of his previous arctic expeditions is just so nasty and awful. Like, yes, Sir John is wrong to undersell the danger they’re in and Crozier is advocating for the correct position here, but that was completely uncalled for and horrible to say, particularly in a command meeting, in front of so many people. And Sir John looks legitimately upset by it too. He gets over it quickly, at least on the outside, but I still feel really bad for him (and I NEVER feel bad for Sir John so this is weird for me).

“But of course we will not be abandoning Erebus, or Terror…” Let’s check back in six episodes and see how that’s going!

Crozier slamming his fist on the table to prove he’s not being melodramatic reminds me of this one post (that I sadly can’t find rn) about Jesus Christ Superstar that’s like “‘CUT OUT THE DRAMATICS’ Judas hollered dramatically.” It’s such an Overall Mood.

I don’t have a developed commentary on this at the moment but it’s an interesting reverse-parallel that Sir John had no concern for Young’s well-being when he was alive, ignoring Crozier’s concerns about moving him from ship-to-ship when he was in such poor health, yet now that he’s dead, Sir John is the one to recommend that Young be buried which Crozier is surprised by, and seems to feel is unnecessary.

There’s been so much amazing commentary already made about Young’s burial scene so I’ll skip it except to say that Hickey’s irritated sigh when he hears footsteps coming towards the grave is SO funny. That’s exactly how I feel when I know that someone is about to tell me something that will annoy me.

Goodsir was really getting into the emotion of Sir John’s “eulogy”/motivational speech before he remembered the promise he made about Young’s ring. Also, what triggered his memory was Sir John saying “We shall earn our loved one’s cheers and embraces,” so no doubt a reminder of the traumatic “Your loved ones will be there in Heaven to welcome you! :)” “I never knew my mother or father” exchange (or maybe just a reminder of the fact that he was supposed to get Young’s ring to his sister but just let me scrape a little humor out of this. God knows I need it).

The shot of Bryant praying in his hammock the night before they get completely frozen-in is honestly deeply upsetting to me. Especially considering he’s a marine so he Did Not Ask To Be Here, yet there he’ll die.

According to Melville, ship’s compasses occasionally spun round-and-round when a ship was caught in a severe storm and this was an incredibly upsetting thing to behold because of how disorienting it was. So, considering that, Fitzjames keeps his composure pretty well but he clearly has some reservations about how things are going and Sir John has no comforting-sounding remark about ‘Magnetic North’ to offer him now.

The bit where Sir John “sees” Crozier, on Terror, turn away from him with a half-smirk on his face is interesting because there’s no way he could have possibly seen Crozier’s expression at that distance and I’m doubtful that he’d even have been able to make out the identity of anyone he might have been able to see on Terror’s deck. So really, it speaks mostly to Sir John’s mental state; his seeing their getting frozen in as a loss against Crozier and imagining that Crozier would see it as a victory for himself.

Ugh the final shot is making me think about @catilinas’s post comparing a shot of the two ships stuck in to the shot of the ink drops from ep 3 and I am LOSING IT but I was losing it anyway because it’s 2AM now and my entire body feels like gelatin.

THANK YOU AND GOODNIGHT!

SEE YOU NEXT TIME!

#the terror#i'm REALLY proud of these!! this was so fun to do!#i definitely intend to do this for each episode#no promises for the timing on that but i legitimately have nothing better to do so lol hopefully ep 2 will happen soon!#hope y'all enjoyyyyyyyy#feel free to add comments if you like or you don't have to! whatever is good - i just appreciate anybody slogging through this lol

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Terror Meta - Tom Hartnell: Symbol of Death, Redemption, and Bravery

By now, I think it’s been established that The Terror’s writers went above and beyond when it came to making their characters. The question board picture has been circulated (including the question of when a character went from being in a high adventure story to horror), so it’s probably not a reach to say that every character had their place in the show carefully considered. And one of those characters is Tom Hartnell.

(Warning: Long post and spoiler heavy. Uh, people die. A lot.)

For the show’s time constraints, Tom’s backstory is mentioned in snippets, mostly in the first episode. David Young provides the majority of it:

“I don’t want you to do to me what you did to Tom Hartnell’s brother. [...] I want to go to my grave as I am. Don’t cut me open.”

Several times in the same episode, references are made to the men on Beechey Island, having been the first three casualties of the Expedition. Clearly, Tom’s brother was one of these three.

I’ve posted this on my blog before, but the original pilot script also gave Tom an extra role and provided deeper backstory, such as this:

With Tom on the Erebus watching Billy Orren drown and attempting to go after him, a role that was eventually given to Collins. And again in a removed flashback to Beechey Island, which provides not only backstory, but further explanation to why Tom is the way that he is:

While this isn’t included in the show, the writers probably kept this scene in mind with his character. Yeah, Tom walked in on his brother’s autopsy. From the very beginning of the Expedition, he dealt with death in the most direct and horrifying way possible. In the sense of the writer’s question of when it went from high adventure to horror? It was probably this moment, before the show even begins.

From this point, Tom is transferred to Terror for reasons not explained, but now everyone knows what’s happened to him. Even people as far down the hierarchy rungs as David Young know, and it makes them uneasy. But here’s where it gets interesting.

At the moment David Young starts coughing, Tom Hartnell appears in nearly every single scene involving a person either dying or about to die. Case in point.

He’s sitting right behind Hickey and looks over his shoulder when David starts coughing. Shortly after, when David retches, he’s standing up and watching him.

(It should probably be noted that David dies of exactly the same disease that killed Tom’s brother. Wuh-oh.)

“Okay, DJ, but that’s just one time. He’s an AB, so of course he would be there!” you might say.

You’re right! But the next time he appears in Episode 2 (”Gore”), look who he’s standing next to.

Lieutenant Graham Gore, that’s who! (And Morfin by extension, but that’s for later. Same with Des Voeux.)

Aaaand who goes next?

(Really big UH-OH.)

And if you want to go by extension, he’s also present when Silna’s father is shot, and is the one assigned to collect Silna’s things that are in the Erebus sick bay with her father’s body in Ep. 3 (”The Ladder”).

Where he looks, appropriately, uncomfortable. @theiceandbones absolutely brilliantly pointed out that yes, this is the Erebus sick bay where Tom walked in on his brother’s autopsy. It stands to mind that of course he’d be anxious. He knocks on the doorframe before he enters, walking in slowly and nervously. His body language here is interesting and hard to capture with just screenshots, but he keeps trying to look away from the body as much as possible, but is finding it very hard to look away. Even as he’s leaving the room, he looks again, while also bodily backing away from it. With his brother’s death in mind, he’s revisiting the place where it all happened, possibly for the first time since then.

While I think his death symbolism starts with David Young, it really picks up between here and the next scene, where he speaks to Silna.

In the short time he speaks to her, a few things are established, both said and unsaid. Unlike some of the crew, Tom doesn’t appear to be uneasy about Silna, but instead is sympathetic. His job was probably just to get her things and deliver them, but he goes out of his way to help her and extends kindness in packing her food. He offers his condolences, and again, in something that is hard to catch in screenshots, he thinks about it for a moment, looking conflicted before offering them and giving her the nickname she’ll have for the rest of the series.

It’s unsaid, but undoubtedly, he’s thinking of his own loss as well.

We don’t see Tom for a little while until near the end of the episode when Sir John is taken into the firehole. And then, sure enough:

There he is. (For an AB, he’s sure showing up with officers quite a bit.)

Tom is in-frame for death after death after death.

It gets subverted (like a lot of things) in Ep. 4 (”Punished, As a Boy”). Tom is not in frame during Private Heather’s attack, which may be owed to Heather not dying. Strong is taken off-screen, and Evans is only with Crozier when he’s killed. He reappears briefly and in-focus, sitting with Hickey and Peglar, when Tozer is talking about how baffled they all are that Heather hasn’t died.

He also doesn’t appear when the Strong-Evans mismatched corpse is found by Hickey, who proceeds to actually see the Tuunbaq for the first time. The next time he’s seen is at a very pivotal scene for not only him, but the entire plot.

At this point, Hickey’s claimed responsibility for capturing Silna, and Tom stands up a few seconds after to also claim responsibility. This is where I think the tone of his subplot changes completely, all in the matter of one scene:

The interrogation.

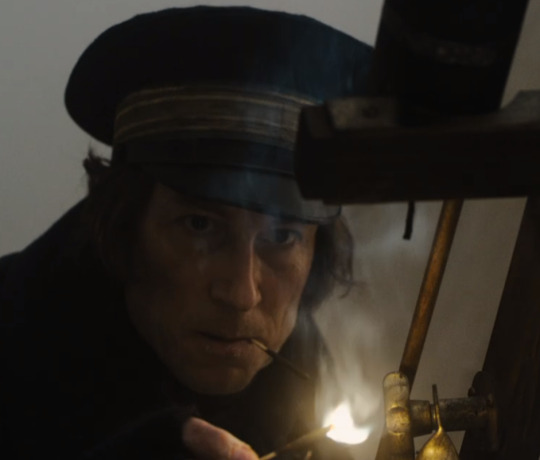

Now the above shot is kind of amazing, and I’ve only noticed it recently, but knowing how much detail the show crew put into this, I feel like it’s relevant to point out a few things. First, this shot is framed with Hartnell in the center and Hickey and Manson off to the side, just after Hickey says that Tom saw the Tuunbaq first. There’s a brief shot of Hartnell sort of side-glaring at Hickey with his lip twitching before he steels himself, and then this composition. Little and Fitzjames are looking at Hickey, but Crozier’s looking at Tom, fully and completely. He knows something, and it feels relevant to note that Hickey is level with a chessboard, while Tom is level with the light.

I’ve posted about Tom’s face journey here before, and I’ll recycle a few shots for this, but the turning point comes just after Crozier outlines what Hickey’s being accosted and punished for. He names the punishment (the lashes), and Tom’s face says it all.

Fear. His eyes are watering. He has to take in a few breaths, but then Crozier asks what do they have to say and without even a full second of hesitation (I counted):

Tom says, “Yes, sir!” as clearly as possible. He accepts the punishment immediately. Crozier’s reaction:

He stares at Tom for a long moment, thoughtful, until Little draws his attention away.

Now, what does this have to do with the theory of Tom being a symbol of death? Well, a lot. I’ll get to that.

First, during the lashing, you only hear Tom’s v/o telling Manson that the lashings will hurt, and that the pain is the point of why they’re lashed. He is deliberately kept out of sight and focus, because the punishment isn’t really for him in the audience’s eyes anymore. He was probably absolved the moment Crozier looked at him. The punishment is completely directed on Hickey after that.

Ep. 5 (”First Shot a Winner, Lads”) is where the change in Hartnell really shows. The episode starts off with scenes of life now. Officers and men are taking measurements of temperature and gauging the speed of sound and light. Fitzjames is working on the charts (towards Back’s Fish River). Goodsir and Lady Silence are talking and translating, and the trinkets from the men are shown as they’ve interacted with her. The show physically leans away from death for a moment, which up until now has been bloody and gruesome. The first person who dies is Hornby, and all that happens to him?

He simply falls to the ground. No blood. No viscera. His heart’s just stopped.

Of course, the next time Tom appears:

He’s handling Hornby’s body and taking it down to the dead room.

This scene is very poignant because it shows how four different characters handle the idea of death and the afterlife, all in very short order.

You have Magnus, scared of the hold because he’s certain he’s heard the voices of Strong and Evans. He’s afraid of the ghosts that he’s sure are there.

You have Irving, who is oddly indignant, technical when it comes to the dead with explaining that all that’s left of them are frozen remains and canvas shrouds, and furious at the idea of Manson believing in ghosts.

Hickey, who at first seems to be doing Manson a kindness, but probably just more eager to show Irving up.

And then Tom, completely unafraid of handling a body, and offering to Manson that he can get the job done if Manson lowers Hornby down.

The next shot we see is another interesting one, with Hartnell leading the way to the dead room, Hickey bringing up the rear, and Manson, the lantern-bearer, several steps behind. (You could say a lot for crossing the River Styx energies here, ya.)

And then the dead room is shown at a Dutch angle or Dutch tilt, a technique used to establish uneasiness or tension.

Manson is watching the two of them work in the dead room, out of the light, in a shot that is off-kilter (yes, the ship is off-kilter as well, but up until this point, everyone has been shown standing upright) to suggest that something is going to go wrong. But then:

Tom steps out of the dead room first, in the lantern light, standing upright against the angle, diffusing the tension. There are no ghosts, no eerie disembodied voices. And just like that, with a quiet affirmation--

The scene ends, with nothing having gone wrong.

To follow up on this in the sense of Tom’s character, he’s gone from being nervous and touchy around the dead to being completely alright with their presence.

Following this, there are more scenes of life against all odds. Tozer is cutting Heather’s nails and speaking to him as though he’s awake. Hodgson supervises another scientific experiment with the cannons. Goodsir and Lady Silence meet with Blanky and Crozier and speak, ending up with the fight that culminates between Fitzjames and Crozier. No one is killed. If anything, this is one the liveliest scenes thusfar.

The next time he appears?

Is when the Tuunbaq is on the ship and about to appear in full. Before, his appearance might have suggested that someone was about to die, but something kind of interesting happens.

The crew fire on the Tuunbaq after Blanky marks it with the lantern fire, and for one of the first times in the show, Tom actually appears happy.

He’s excited! He’s standing with Little, Hodgson, and Tozer, and they’re all thrilled. Even more amazing?

Blanky does not die.

He’s injured. His injuries require a pretty gruesome amputation, but of all the episodes in the show, Ep. 5 ends with the lowest body count.

Now Ep. 6 (”A Mercy”) is kind of all over the place for Tom and everyone else. He appears first talking to Hickey about Armitage, who is now revealed to have been part of their plot to kidnap Lady Silence. Hickey asks why Tom didn’t turn Armitage in, even after being flogged.

Hickey: You’d have been in your rights to.

Hartnell: I didn’t see the point in it.

Hickey: Even still? After getting flogged? That sort of thing can change your sense of what the point is.

Hartnell: It did. I’m grateful... is the point.

Hickey: [pause] Reformed you, did it?

Hartnell: I shouldn’t have listened to you. And I deserved to be flogged.

Hickey: [silence]

Hartnell: Yeah, and by ordering it, the Captain, he’s given me a chance to clean my record and start anew.

Hickey: Do you think Crozier sees it like that? A new Mr. Hartnell?

Hartnell: I do, yeah. [smiles] And I intend to use that charter well.

This is another turning point for both Hartnell and Hickey. Hickey is realizing that his list of allies is getting shorter (he starts by trying to drive a wedge between Tom and command, reminding him that he physically suffered because of them, and when he realizes that it isn’t going to work, he mocks him and leaves him) and now understands that Tom probably won’t work with him again.

Tom shows that his loyalty is now completely with Crozier. I’d even say that he never followed Hickey’s ideals in the first place, even with the kidnapping (remember how he acted toward Lady Silence before, and how quick he was to be held responsible). This is him now completely, as the phrase goes, on the side of angels. It’s going to add a new tone to his next few interactions, and really drive home his place as a death symbol.

Ep. 6 is as bloody and horrific as Ep. 5 was not. Fitzjames holds his Carnivale, Jopson and Crozier attend, and it all goes wrong very, very fast. One thing that @theiceandbones and I noticed was that before it-shay hits the an-fay, Tom is seen once in costume.

And he’s dressed as what appears to be a lion - a very poignant symbol of bravery (and Britain, if you want to go that far).

Of course, during the fire, Tom is there (as is everyone except Hickey who is outside of the tent), so I’d hesitate to call that a connection. His first mention after Carnivale is through Bridgens, who tells Crozier that Tom reported Dr. Peddie lost during the fire.

Going into Episode 7 (”Horrible from Supper”), Tom is officially an outlier to the people who are going to become the Mutineers. He’s excluded from anything Hickey begins to plan and is completely on the captains’ side. Literally. His next shot shows him between Crozier and Jopson.

But more relevant is the next time he’s seen with Crozier and Blanky, making notes of the ice and the movement of the compass. Blanky remarks:

Tom’s been completely redeemed in the eyes of Crozier, enough that he’s being asked to step outside the grunt work of hauling sledges, and his opinions and observations are trusted (”Very well. I’ll continue to rely on your eyes.”). The way he gives his observations also show an uptick in confidence and enthusiasm. He’s happy, and a far step away from his nervous, mournful attitude of earlier episodes.

Has he stepped out of the role of being a death symbol? Yes, and no.

Death has started to dog the crew of the Expedition again. Madness is seeping in with the lead. Hickey begins to weave the tapestry of his mutiny as the gruesome discovery of Fairholme’s party takes place (note that Tom isn’t present for this). Rescue seems impossible, and death is starting to become imminent.

Tom Hartnell’s role begins to change, and he goes from being present at the deaths to aiding in the recovery. Whereas death is everywhere, Tom is a symbol of something gentler (on a whole, this is talked about beautifully in this meta piece).

It starts with Morfin.

Remember that Tom was in the shot with Gore, Morfin, and Des Voeux in Ep. 2, and he’s seen with Morfin again with Lady Silence’s father in the Erebus sick bay later. His role changes with Morfin in Ep. 7 (I’d even through in the symbolism of Morfin singing The Silver Swan if we really want to go wild with the death icons). Morfin is shot, put out of his misery effectively, and Tom does not appear until after he is killed. More importantly, he’s now interacting with the scene - helping, as it were.

He’s at the center of the shot with Goodsir - not Morfin, who is technically the subject. His hand is on Goodsir, and he silently says something to him before Goodsir stands. Unlike with the other deaths, Tom is no longer directing his attention on the bodies, but on the people who are dealing with them.

Further on, he privately speaks with Crozier about Armitage’s involvement in Hickey’s earlier plot. Once more, he’s on Crozier’s side completely, which Crozier affirms for him, saying that he trusts him and does not want to put him in a position where he feels like he can’t speak. He says they’ll work together, and thanks Tom, earning a smile out of him.

D’awwww.

But back with his death symbolism, Tom is the first shown to be handling Morfin’s body, drawn into sharp focus against the corpse.

He’s responsible for the handling and burial, but rather than appearing nervous or upset about his job, he handles it as he did with Hornby’s body. It’s a job to do, and one that he doesn’t appear to mind doing anymore. He helps dig Morfin’s grave, juxtaposed with shots and conversation of Crozier talking about the lead in the cans that led to Morfin’s madness and death.

The episode ends with Jopson’s promotion and the start of Hickey’s bloody mutiny, in a way signaling the beginning of the end.

Tom doesn’t appear for a portion of Ep. 8 (”Terror Camp Clear”), removed from Irving’s violent death where he probably would have been before, and instead placed in the silent, mournful atmosphere of the dead Netsilik group.

He’s also removed from the general chaos of the imaginary raid on Terror Camp, but appears in probably one of the most pivotal and brilliantly-arranged scenes that he gets in the entire show.

The Tuunbaq attacks in full force, ripping the camp asunder, causing so much chaos that the mutineers manage to get away. Men are killed left and right, gruesomely torn apart. The fog makes it difficult to see what’s happening and where, and so only the sounds of roaring and screaming indicate what is happening around them.

And then there’s Tom.

He’s scared. Of course he is. He’s seen what the Tuunbaq can do, and he knows it’s coming. All he can do is tell the men with him to get down and out of sight, while he stands.

Trembling, he raises his gun and waits for the inevitable. He was on deck with they shot the Tuunbaq with the cannon, and he knows that even then, it got away. He knows its size and what it’s capable of doing. His gun will do nothing to it, and he knows this. All he can do is buy the men time and take at least one shot.

Tom Hartnell literally faces down death itself, and does not back away.

The camera pans in on him, drawing into focus how he steels himself, furrowing his brows, keeping his aim steady. If anything, this shot establishes his bravery in full detail. And then--

A rocket is launched at the Tuunbaq from behind -- completely parallel to Tom. In a similar focused shot is Fitzjames.

Complete with the same steely resolve and surety, establishing his own bravery. With him on one side and Tom on the other, the Tuunbaq is caught in a perfect intersection of selflessness and courage, even when no one’s around to witness it (”A man like me will do amazing things to be seen.”).

Ep. 9 (”The C, The C, The Open C”) opens with Lady Franklin formally, but with Tom and Golding on the Arctic side, dealing with the dead in the day after the attack on Terror Camp.

Once again, Tom is no longer present during the deaths, but is dealing with the aftermath. He offers to help Golding move the body. Golding wonders after the identity of the body, clearly shaken by what he’s seen. But Tom, turning his focus way from the corpse, puts his hand on Golding’s arm to comfort him, as he did with Goodsir.

“That won’t change what we do for him.”

It’s no longer a matter of the how’s and why’s, but rather how the men move on. Tom has come to represent something so much more in death than its execution. His own grief was mired in the memory of his brother and what was done to his body. Lashing out, curling into himself, allowing others to control his path, and then finding his own way to redemption, Tom has made the full walk of his own sorrow and gone through its stages, coming out on the other side with the sense of mind to help others cope with their losses.

Then, he’s standing before the row of the dead, hands respectfully folded in front of him. He’s in their presence again, but not in the violent hour of their death, but again, in the aftermath.

Crozier’s speech is examined so, so gorgeously in this post, with the words “courage” and “the end” focused on Tom. @theiceandbones also pointed out (and subsequently broke my heart) that after Crozier mentions bringing home the names of the dead so that their loved once can find solace, Tom’s bottom lip is trembling. I fully believe in his character, Jack Colgrave Hirst chose to keep the real Thomas Hartnell’s life in mind, thinking that he was going to have to go back to their mother with news of his brother’s death. He embodies this concept so well in that moment.

After Fitzjames’ death, Tom is seen again in that same role.

He’s at the center of the shot with Fitzjames’ body, sewing him into his shroud, surrounded and at the center of the focus of their party. He’s either volunteered or been chosen to the handle the body, which he does respectfully. As Shannon, my brilliant cohort noticed:

He’s working diligently and carefully. And again, it won’t change what he does for him.

Tom also helps with Peglar, who he has been shown with multiple times since the very first episode, possibly suggesting that they’ve been friends all along.

He helps lift Peglar into Bridgens’ arms, clearly worrying for him.

He’s not shown during Peglar’s death, but he helps handle him, allowing him to rest a little easier before he quietly passes on. Compared to what’s been happening in the mutineer camp, what Tom’s witnessing is a gentle passing of people.

It’s the last scene that stings the worst, as Crozier’s group is confronted by the mutineers, including Des Voeux, Hodgson, and Manson.

Des Voeux’s gun misfires, hitting Tom square in the chest.

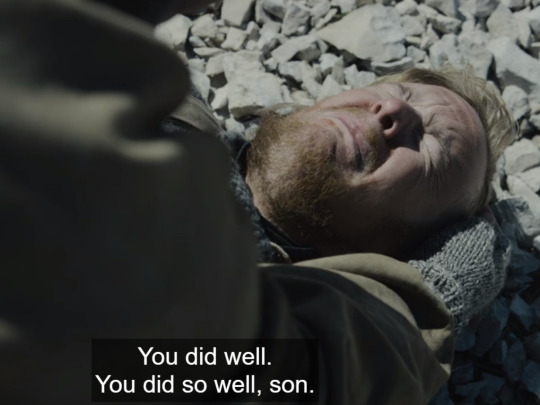

Tom’s own death is not through the Tuunbaq, or through any of Hickey’s machinations, or anything more than an accident. It’s quick, but painful. Crozier kneels beside him, stroking his hair, comforting him as Tom’s done for others before. The next few lines speak for themselves.

It’s the end of Tom’s redemption, a sign of his bravery, of his own recovery and progress. Crozier calls him son, affirming a bond between them. Tom is not dying alone. Instead, he has someone at his side who cares for him, just as Tom had been for his own brother only a few years before.

He holds on, struggling against the agony of his wound, until Crozier, eyes filling with tears, lets him go with one phrase -- one that includes something that hasn’t been mentioned since Ep. 1.

John Hartnell hasn’t been mentioned since the first episode, and it’s been several years at that point since his death. But Crozier knows what Tom’s been through, and he’s certainly seen his displays of grief and development. If anything would cause Tom to let go, this would be it. With it, Tom goes quietly in only a few seconds. He goes without a sound, simply closing his eyes and letting out a breath.

Des Voeux, shaken, asks Crozier to stand up. With it, Crozier does Tom a final respect by asking Little to bury him, and to live. Tom’s body is kept out of sight completely, not seen again.

After his death, the others go quickly. By the time of Ep. 10, it’s almost wholesale loss, between Goodsir’s heroic suicide, the Tuunbaq, and others just disappearing into the mists of the Arctic. But Tom’s character appears to have represented a balance, showing grief and loss, but also recovery and redemption. He appears with nearly every major death in the show, going from anxious and shaken to brave and kind, more eager to help those left in the wake of death, making him the perfect representation to the concepts of loss, grief, and recovery for The Terror.

#amc the terror#terror blogging#thomas hartnell#jack colgrave hirst#meta#long post#really really long post#i just really love him a lot#this was originally titled THE TOM HARTNELL GRIM REAPER THEORY

355 notes

·

View notes

Text

day 2: tears wiped away

@theterrorrarepairweek

rating: g

characters: collins, goodsir

word count: 954

read on ao3

buy me a coffee!

healing was a long, slow process.

not that henry had ever expected things to come quickly; he had thought his broken mind like any other wound, mending over the course of a fortnight or a handful of weeks, at most. but instead his stay at rosebank stretched on for months, swinging between tentative peace and deep, dark despair.

the goodsirs had been kind to him, harry and his sister and all their brothers. they’d let him stay here, at their home in anstruther- though soon the house was empty again save jane and harry and henry- and barely bat an eye at housing and feeding him. henry tried to make himself as little of a nuisance as possible: he split wood and washed dishes and did his own laundry and mending, running errands for miss jane and doing odd jobs about town when he could. she wouldn’t take the money that he made to try and pay her back for her kindness, so he hid it amongst the mail every once in a while in unnamed envelopes.

and harry, oh, harry, who had always been gentle with him, and understanding, even when the world was falling apart around them. that place had exacted a price on him, too, had taken something from him and twisted him into something else, but harry had kept the good parts of himself as other men buckled and crumbled under the weight of it all.

he had held him in the dark and listened to him cry, had wiped away his tears, and then he had given him a home.

it was of course a given, then, that henry loved him. anything else would have been unthinkable.

henry did not expect anything of harry. he had already given up so much of himself- he knew the deaths weighed on him, that he counted some as personal failures- that henry couldn’t possibly ask him for more. and he wouldn’t have wanted to, even if he could, because henry knew that he was not a thing to be wanted- that he was too strange, gone wrong in the head, too broken- and he’d not burden harry with his feelings.

but that didn’t mean that he didn’t still feel them.

there was something achingly exquisite about living in the goodsir household, and that was that he saw harry every day. It was a double edged sword; spending time with him calmed something in henry, fulfilled some sort of bone-deep longing, but it also reminded him at every turn of the things he could not do, and he found himself on multiple occasions reaching for harry only to drop his hand at the last moment.

it was good, though, to have something to himself, something small that he could hold close, because it had been so, so long since he’d felt warm- he’d been afraid that the ice had stayed in his bones just like the lead, a terrible reminder of years he’d give anything to forget. and henry was content like this, happy to be at peace, to be useful, to be near.

much of him recovers, in those months in anstruther, mind and body; not perfect, he’ll never be what he was before, but better. his joints still ache, sometimes, especially in the cold, and especially in his hands. he settles himself by the stove for most of the winter, and he apologizes to miss jane for lapsing in his chores, but she waves him off in a way that would have been brusque if not for her kind smile.

“don’t worry your head about it, now, mister henry,” she tells him, “we’ll get along just fine.”

so, he finds himself a blanket- the biggest he could get his hands on- and sits by the warmth of the stove and tries to learn how to knit.

the others occasionally came to keep him company. jane sat with him in the evening and sewed or instructed him on how to properly darn socks or scarves; polly came and curled herself in his lap, snug and purring so loudly he could feel it; harry would pull up a chair or sit cross-legged on the floor and read by the dim, flickering light until he was squinting. that was perhaps one of henry’s most favorite times, just the two of them sitting in quiet contentment, together.

it was under those circumstances that it happened, then, because of course.

harry had been on the floor pouring over some new paper sent by way of edinburgh, his reading glasses slipping down his nose, and henry had been bent over his knitting, desperately trying to salvage the mitten he’d been working on. and then suddenly harry had been very close, leaning up and braced with his hands pressed just above henry’s knees, their mouths pressed together in a dry, functional, and quite frankly terrible kiss.

but it freezes henry regardless, his entire body going very, very still, and when harry pulls away, he looks worried, almost panicked. He stumbles over his words, apologies, excuses, but henry doesn’t hear them, not really, he just –

“harry.” he must know, suddenly, needs desperately to know more than he’s ever needed anything else in his entire life. “did you mean it?”

he reaches out and this time he doesn’t shy away, his fingertips lightly skimming harry’s cheek, and harry sighs a little and leans into his palm, eyes dropping shut. he says, “of course.”

something in henry’s chest seems to burst, then, warm and bright and

wonderful,

and he smiles- it feels like a lifetime since he had last smiled. but harry had kissed him, and he had meant it, and in the end that was all that really mattered anymore.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Halloween Terrorfest, Day VII: ‘A disquieting metamorphosis’

(A note: This one was hard to write -- I always get so neurotic about writing James and Francis because damn it, I must do justice to Mr. Harris and Mr. Menzies’s wonderful performances! And don’t take a shot every time I’ve written ‘Francis’ here -- you’ll black out, but it’s not a fic about our favorite captains if they’re not saying each other’s name so many times!)

(TRIGGER WARNING for general death.)

The wind whistling past his ears is what wakes him. Above him, the endless grey expanse of the sky, beneath him the pebbles pressing into his back. He raises himself on his arms and, sitting up, realizes that the movement does not cause him the pain he’s been living with for God knows how long. He stands and the familiar ache in his bones does not make itself known. He takes a step, and another step, and finds he can walk without impediment. A memory comes to his mind, hazy for half a second before crystallizing.

‘Then you are free, hm? Mine your courage from a different lode now -- friendship. Brotherhood.’

‘Are we brothers, Francis? I would like that very much.’

Francis. Where is Francis?

James looks around him. The sky, the ground, the horizon and nary a soul in sight save for himself. How he came to be here, he realizes, he does not know; the last he remembers is the tent, the candlelight, Francis’s hand in his own. Something burning in his throat, a deep sleep. No matter to that. He must find the others, find Francis. So he sets out, walking in what he hopes is the direction of Back’s Fish River.

He walks and walks and still he feels no pain, and wonder how he’s healed so well. No matter, he reminds himself. He can think on it later, when he has the time. He can think on it when he has seen everyone set foot on English ground.

Day turns to night and night turns to day before he stops and notices that he is not tired as he always was before. Another puzzling revelation to forget until the time is right. He should, he supposes, be grateful for this newfound strength.

Another day and night he walks and, when he thinks he will never find them (we were all so ill, he remembers now, how could they have gotten so much further?), he sees in the distance a rounded shape. Whether it is a rock or something living he is too far away to know, but he treks on towards it. With any luck it will at least be something abandoned in their journey.

As he approaches he can see its fur; an animal, then, or one of the Netsilik. He does not speak the language, but if there is anyway he can make his intentions known, he will attempt to. They may have seen some trace.

‘Hello!’ he calls to the figure (a person now, he thinks), who does not take notice. He calls to them again as he gets closer, and still they do not turn around. They remain in their spot, hunched over, and James has to walk around in front of them to see their face.

Oh. Oh, God.

Looking right at him--

‘Francis?’ James asks, his eyes stinging. ‘What are you -- where are the others?’ A question without a point. Dead, of course. But here he is, and here Francis is. A surplus of luck indeed.

Francis stares at him. No. He stares at the ground James kneels in front of. Through me. He is looking through me. James swallows, blinks his eyes once, twice, thrice. He says Francis’s name again and receives no response. He reaches out and lays a hand on his shoulder, feels the slope and muscle beneath layers of fur and still Francis does not so much as twitch. James draws a shaky breath. What is wrong with him?

‘Are you alright?’ Nothing. ‘Francis, I’m… my hand, it’s on your… my God, I’m right here.’ It’s harder and harder to speak. ‘I don’t know where I’ve been or where everyone else is, but I’ve been walking for days. We can’t be so much further from the river.’ Still nothing. ‘Do you understand?’ He hears his voice trembling. ‘Do you… do you see me? My God, Francis, what’s happened to you? Have you lost your senses?’ The questions go unreplied, and his hand falls as Francis rises, walking in the direction James came from. James runs after, falling into step beside him and unable to keep back the tears despite knowing they will freeze to his flesh in this cold.

‘Is it me? Is there something wrong with me -- damn it all, Francis, can’t you at least make clear that you can hear me? I’m here. I’m right here.’ He tries to seize him by the arm and turn him round, but Francis slips from his grasp and keeps walking on. ‘Please. Please, let me -- what is wrong?’ James pleads, his vision clouded, at an utter loss for any other words. Is Francis angry with him? Has he lost all sense and cannot hear nor see nor feel? Has he gone mad? Or is it I who am mad? Or am I in Hell, and this is my punishment?

‘Captain!’ a voice calls behind him. ‘Captain Fitzjames!’ James turns around, relief and despair flooding him in equal measure: someone can see him, someone can hear him, but Francis cannot. Then he is angry with me. What is it that I have done? How will I make it right, if he is this furious?

Goodsir and Hartnell stand ten feet from him, their coats snapping in the wind. Goodsir walks to him. ‘He can’t see you, sir,’ he says softly. ‘I’m sorry. He can’t see you nor any of us.’

James’s mouth is dry. ‘What do you mean?’

‘Captain.’ Hartnell glances at Goodsir before looking at the ground. ‘What’s the last you remember?’

‘Sleep. I fell asleep…’

‘Sir.’ Goodsir shakes his head. ‘I don’t know how to tell you any other way. Captain Crozier is the only one left alive.’

‘Then you are…’ James laughs a laugh that rings half-mad in his ears and shakes his head back at him. ‘No. I must be dreaming.’

‘You’re not, sir. All of us, we’re -- we’re trapped here. Whether we’re our souls or ghosts none of us can say but we’re trapped here. We’ve been keeping an eye on him for some time now; we thought perhaps you had been luckier than we had.’

‘Then what?’ He is angry, all of a sudden; why, since they had to die, are they not relieved of this place? Why can they not know some semblance of peace, after everything? ‘What is there now?’

‘The rest of us,’ Hartnell says, ‘and not much else, I’m afraid. But, Captain…’ He swallows. ‘Will you come with us? We’ve a camp and we don’t need for food or sleep. Mr Bridgens and Mr Peglar have been retrieving the books we left behind.’

‘No.’ James can hardly hear himself speak. ‘I’ll stay with Francis. I’ll not be able to make trouble, will I, now,’ he adds wryly, his voice trailing off miserably to reduce the question to a phrase.

‘He’s alright as he’ll ever be,’ Goodsir says. ‘We find him every day. There’s a Netsilik band taken him in, Captain. He’s one of theirs now.’

‘And Lady Silence?’ James asks, and regrets asking when Goodsir’s face falls. ‘I’m sorry.’

‘She’s gone,’ Hartnell says. ‘They exiled her for losing the creature. We’ve yet to see her. But you’ll still see him every day if you come with us, Captain. We’ve missed you.’

‘I’ll not come with you right now. Perhaps I will find you in a few days, but I want to see him with them. I want to know that he’s found some kind of life here.’

‘Alright, then.’ The corners of Goodsir’s mouth lift in an attempt at a smile. ‘We’ll see you sometime.’ They turn and leave, trekking away to the east. James watches them; they seem to disappear into the encroaching fog after a while. He turns in the opposite direction and follows in Francis’s wake. Please, he thinks, let him have some kind of family, some kind of joy with them. He needs it as much as any of us, perhaps even more so now.

#halloweenterrorfest#day 7#the terror#the terror amc#james fitzjames#francis crozier#tom hartnell#harry goodsir#(there's a version of this story in my head where francis can see james but i decided this was better for a shorter story)#tw death#akh's writing#akh.txt

1 note

·

View note

Text

Nothing Like The Sun ~ A Terror fic (on AO3)

(I was blown away by @alessiapelonzi’s gorgeous Goodsir/Lady Silence art – who wouldn’t be, honestly? – and got inspired to write a little missing scene from Episode 7... Enjoy!)

Harry is at first puzzled when he wakes, for while the hour has clearly grown late, the soft halo of lamp light still illuminates the tent’s canvas walls. He must have left the lantern burning, he realizes, fallen right asleep before he had a mind to put it out.

But it is not solely the light that is responsible for his confusion, as there is also the matter of the position of his body on the pallet. For he had somehow shifted in his sleep, turning over from his right side onto his left, an ostensibly blameless act, and yet now he finds himself lying face to face with a woman – an unattached, unmarried woman – and one who is evidently just as awake as he is.

Silence is still, unreadable as a sphinx, her eyes a pair of dark and fathomless globes.

It will not do. He must convince her at once to return to her own tent, or at the very least make his excuses and retreat to a further corner of his own. He must think of her reputation, for what should happen if it were put out among the men that she had come into his tent at night, even if her purpose was entirely innocent? Harry knows that many of them already think her a savage or even a conjurer. It is pure rot and foolishness, born out of ignorance; still, he would not have them imagine her the surgeon’s doxy as well.

Despite the impropriety, however, he cannot yet bring himself to move. Lying next to her underneath the wool blanket, he is warm and snugly comfortable, more so than he’s been in months, perhaps even years. All points of reason tell him that he should be more shocked by her presence, by the manner in which she came into his tent, by the familiarities she took in laying down beside him. (Her hand is still there, clasped along his shoulder, steady as an anchor and warmer besides.) But there is no outrage in his heart, no recrimination. There is only gratitude.

His mind had been in such disorder following the events of the night, his thoughts overrun by a terrible plague of images from which he could find no escape: Dr. Stanley staggering towards them, engulfed in flames; the small and lifeless body of Jacko as it lay folded inside his wooden trunk; poor Morfin’s blood staining dark against the shale. It was all he could do to stumble back to his tent before any of the men saw him in such a wretched state, unable to speak from weeping and trembling. Part of him is still ashamed she had to see him that way at all, as helpless as a child terrified of the dark. Even now, he feels as if he must explain himself, or else apologize for being so uncharacteristically out of sorts.

“I –” he begins, and the words fail him, as he knew they would, for it is clear that he can no more make sense of himself in English than he can in Inuktitut. And so he settles on something that he thinks will lose little in the translation. “Qujannamiik,” he says softly. Thank you.

Her lips curl upward into a tiny smile – a rare gift indeed, precious for all that they were so infrequently bestowed – and she momentarily glances away, almost bashfully, before returning to meet his gaze once more.

She slowly lifts her hand from off his shoulder, a sign, no doubt, that she intends to take her leave of him and then depart. But rather than turning to go, she does something entirely unexpected. Reaching up, she curls her fingers through the thick of his hair, just above his ear, the base of her palm smooth and warm against his temple. His body stills from the shock of it – and from the pleasure, too, for it is an intimate gesture, and he has been starved of tenderness for such a long time.

Her hand traces down along the side of his face, nestling in the untamed riot of his whiskers, her thumb coming to rest on the edge of his wind-chapped cheekbone. Harry closes his eyes, for some part of him cannot bear to have her touch him in this way, not when all they’ve brought to her is misery, while still another part of him is certain he will perish should she ever choose to remove her hand from where it sits upon his cheek. More than anything, he is overcome, by what sentiments he cannot entirely be sure, and yet it is clear that something has shifted between the two of them, irrevocably so.

He opens his eyes to the light once more, seeing her anew, his mind thinking only to memorize how the shadows are falling upon the planes of her face, the way the blades of her brows arch and narrow into graceful points.

Dear Lord, she is lovely, he thinks, serene as a Diana cut from marble.

In the months of their acquaintance, she has been so many things to him: at first a teacher and a pupil, and then a companion, and perhaps even a friend. The time they had spent together on Erebus was some of the happiest he had known on the voyage, the hours in between their meetings often counted down in keen anticipation. For it was not only the joint project of the dictionary that brought him such joy, but the diversion of her company. She was curious and bright, easily making sense of some of the more abstract vocabulary he had proffered, and was possessed of a sharp humor that often required little in the way of translation.

Sometimes Harry wonders if in fact he owes her some portion of his sanity. His symptoms, compared to others of the crew, are not so markedly acute, and her presence – during the cruelest part of an already harsh winter – had allowed him a full month’s reprieve from the darkness that seemed to overtake the spirits of so many of the men.

But gratitude alone cannot account for the way his heart is now beating, so thick and ponderous, how his breath is gathering impatiently in his throat, all his senses aflame with the immediate and profound realization of how little distance separates them on the pallet.

Compelled by nothing resembling rational thought, he leans forward, and with a tilt of his head, gently presses his lips to hers, finding them full and pliant, if only a trifle cool. For a moment, he is lost, awash in heady and unfamiliar sensation, only to be sharply torn from his reverie by the sudden awareness of what he has just done. What kind of man was he, to take advantage of her in such a base, impulsive fashion? And what must she think of him now? He pulls back from her, his cheeks hot with shame, wanting at once to stammer out an apology – yet again – but before he can, her hand tightens just so upon his cheek, keeping him from retreating any further, and she moves closer to brush her lips against his.

It is not a kiss of passion, but neither is it entirely chaste, for there is a yearning in it that cannot easily be classified. There is a strange melancholy to it, too – a sense of endings wrapped within beginnings, of things both lost and simultaneously found. And then it is over, and she turns her face upward to place a single kiss upon his brow, soft as a benediction.

Harry watches as she relaxes back down upon the pallet, curling herself slightly inwards as if she means to stay and sleep beside him for a time. He knows now that he will never ask her to leave – if he had ever a mind to heed the dictates of propriety, he possesses it no longer – nor can he truly bear the thought of being anywhere else but here, right next to her, with the weight of her fingertips like a gentle brand upon his skin. Her eyes flutter with momentary drowsiness and he finds himself wishing he could devise some system of notation that might keep her, just as she is, within the gleaming halls of his memory.

Had he but time, Harry thinks, he would write a dictionary dedicated solely to her, giving definition to each gesture and expression, artfully translating the span of her neck and the color of her eyes into every language he knew.