#it's an adult nonfiction book and this looks like a child's craft project

Text

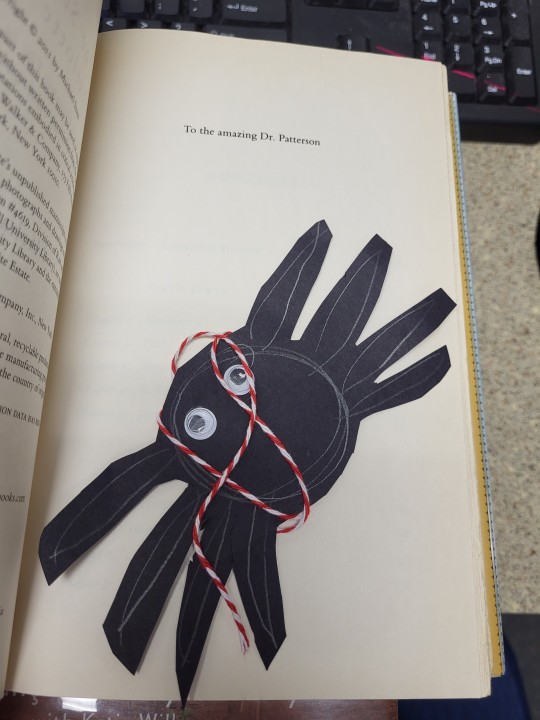

Found a small stowaway in a returned library book today

#ragsycon exclusive#I'm just. look at it!!!#is that not the sweetest thing ever.#it's an adult nonfiction book and this looks like a child's craft project#so i have to wonder if a kid didn't see their grownup reading about Charlotte's web and decided to make a Charlotte to go with it

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

(REVIEW) Luminous and Curious: Try To Be Better anthology, ed. by Sam Buchan-Watts and Lavinia Singer

Maria Sledmere reviews Try To Be Better (Prototype, 2019), a new anthology of poetry and art edited by Sam Buchan-Watts and Lavinia Singer, and inspired by the work of W. S. Graham.

> ‘Graham’s relationship to his “drawings” is curious’, Natalie Ferris notes in her essay ‘Water Water Wish You Well’. Ideas of the luminous, wishful and ‘curious’ underpin Prototype Press’ new anthology of works for and in response to W. S. Graham. Try To Be Better is advertised as ‘a multi-disciplinary engagement with the idiosyncratic creative practice of W. S. Graham, foregrounding experiment and process’. There were many events and publications in 2018, marking Graham’s centenary year, but something about this project stands out. The question of how to innovatively engage with another writer’s practice is complicated: for Boiler House Press’ recent anthology for Denise Riley, it was a question of The World Speaking Back…: an open commemoration and reciprocal gifting, an object designed to constantly generate, speak, respond. With Try To Be Better, a compendium of visual materials, poems and nonfiction, the relationship between contributors and Graham’s work might be something more like watercolours seeping through the long-durée of a remarkable oeuvre. Following the editors’ archival work on W. S. Graham, it forms a processual archive of where Graham’s work has led us and might yet lead on. To read it is to eavesdrop, deliciously, on the free associative musings of others.

> Inclined to the notion of draft, sketch and experiment, the anthology asks of us a different mode of reading, one which deals in instinct, play and free-floating spirit. Printed on joyously yellow pages, in full colour with separate encasing booklet, it’s the kind of text you would slide out for a spare minute, something to dip into in flashes. And yet its curation is also exact and lovely. Yellow pages implies index, directory, a place of cross-reference. The kind of intersections and ‘emplacements’ found in Try To Be Better are transient anchorings of voice in language, language in voice, place in time: ‘And almost I am back again’, as Graham writes in his poem ‘Loch Thom’. As its title implies a kind of iterative act towards hope, Try To Be Better demands of its readers many acts of return and yet evolving pleasure. You sense a little magic between the lines, like a notebook always on the brink of being finished, folded over and over, creasing, its pages thickening with ink. Delicious to read; a kind of menu display of materials in full. You can read it in a non-linear, indexical way. You don’t quite know where you might end up. The first time I read it, waiting at the station, I looked up and saw one of its contributors, the poet Callie Gardner, sitting in the window of a passing train. You sense that the anthology was set up for making sparks of connection and coincidence. I had to look twice, as though I’d encountered a glitch — but it really was Callie in the carriage. I alighted the train, even if I got my routes mixed up later.

> The ethos and structure of Try To Be Better is set out in the editors’ introduction: ‘The changeable and tactile design, together with unconventional indexing, aims to reflect a conception of the notebook as a device with a life of its own, prompting further experimentation and collaboration’. Contributors were given prompts, phrases and quotations gleaned from Graham’s notebooks, whose ranging veers between the elliptical and specific. Many of the prompts question the nature of address, the relationship between text and world, the ‘scene’ of writing: ‘I am only practising how to speak and to speak myself out of myself’, ‘I speak out of a hole in my leg’, ‘taking a line for a walk’. An accompanying index of prompts allows you to follow the walk as you will, crossing back and cutting diagonally. I think of the starts, jumps and fits of conversations between poets and artists, teeming with references, diversions and flights of thought. It makes sense to suggest, as the editors do, that Try To Be Better might even serve as ‘a workshop’ in itself. The list of contributor biographies at the back is reflective of this: the anthology bears works from painters, poets, critics, editors, sculptors, a practicing psychoanalyst, graphic designer, essayists, illustrators and book-makers.

> I like to imagine the book somehow summoned Callie, that day in late August, or was it July, when I took it for a walk. And it summoned many other voices, the more I read on, thickening in chorus and bleeding between hues of voice and form and song. ‘Try To Be Better’, apparently Graham’s ‘catchphrase to friends’, makes me think of sheets of paper thickening. Attempts not scrunched and tossed in the trash but layered upon. A strengthening palimpsest of endless experiment, drafts accumulated, failures written over enduringly. And we keep adding watercolour along the edge, letting the colours melt close to the centre, which glows a sweet, yolklike yellow. And we encounter a failure of presence in favour of motional attempt, the work of poetic kinaesthetics: ‘in the water speech acts flail’ (Daisy Lafarge, ‘Notes Toward an Erotics of Wading’). Maybe the page is more like a mesh. It has been erred on so long, catching accidents and planktonic notions! ‘The passage through language, for Graham’, Ferris writes, ‘was like moving through netting. This was a sinuous drawing in space that enacted what his poems explored, an act of disassembly to perceive the glimmer between the gaps’. It’s this glimmer the anthology so beautifully pursues. These are not poems directly to or for the poet himself; Try To Be Better is not a work of collective elegy or commemoration so much as a dynamic workbook for thinking through Graham’s ideas in ongoing response and practice. It is full of slippages, overlaps and resoundings, in tune to Peter Riley’s claim of Graham’s work that ‘[m]ultiple mixed metaphors proliferate until there is no ground whatsoever under the reader’.

> There are resonant flavours of Graham’s work, of course, throughout the anthology. The way a painted scene reveals the process of painting the scene: ‘The snow is everywhere and even a painter / would only see white in it, but I want to use the perfect word’ (Aisha Farr, ‘The Perfect Word’). As though there were a keystone colour or word to unlock the rest, but we learn it is only in the dance, the layering, the texture, the increment of a motional moment: ‘On quiet cloth I see, / Scrawled like first of angel’s script’ (Graham, ‘By Law of Exile’). There is something of an emphasis on ‘craft’, on the visual, sonic and tactile, that runs through all these works. A voice has a vibration, a summoning of or against silence, the performative ‘Wheesht wheest’ that starts and ends Will Harris’ ‘Moon Poem’: ‘This feeling though — the lull I like, / the hum of your valved voice’.

> The move between presence and absence in poetry is another recurring theme, set out in Natalie Pollard’s essay ‘Hide and Seeking with W.S.G.’. Pollar moves between close readings of Graham’s poetry and the work of child psychologist D. W. Winnicott to explore the ‘linguistic games’ that Graham employs to think through ‘adult and childhood fears about being discovered and exposed’. There is a tension between intimacy and distance, past and present, touch and evasion held in Graham’s work that gives rise to Pollard’s assertion that ‘[f]or Graham, a rehearsal is not so much a warm-up activity as the act itself’. This emphasis on performance, draft, the unfinished motion towards is found elsewhere in Try To Be Better. I think of the sections of leg-as-object in Paloma Proudfoot’s series of sculptures, the colours weeping into each other like sedimentary traces of muscle, the body as molten geology. The poem as ‘touch’ and ‘collapse’ of ‘experiential syntax’, a ‘moment’ ‘shucked’ (Nuar Alsadir, ‘Idea — Subject — Love and Myself? What?’). Bobby Dowler’s ‘Painting-Object_03(C0I-I6)’ is an abstract representation of block colour’s material excoriation within black lines that do not always meet. It works with that Graham-like pull to excess in a sigh, a brush lain down, a rolling river. In Ben Sanderson’s ‘Love Apples’, there is more like the tendrilling watercolour motions of the flesh in its gestural, tactile poetics of time: kisses of fruit and sand and sky.

> Such tactile poetics (borrowing this phrase from Sarah Jackson) feel elsewhere extra fleshy. In Tom Betteridge’s ‘Please Don’t Leave Me Away From You Like This’, there is a shucking and flaking of meaning. Parenthesis mark the anatomical conditions for speech, images of ‘blood’ and ‘suture’ implying that the ‘course’ of expression involves a wound, a ‘linty’ trace, a bodily fade: ‘(in live movement and structure the quiet / wound resembles the human larynx)’. What seems self-contained about Betteridge’s poem in fact forms cell-like, fractal association with many other concerns within the collection: the idea of ‘writing / out of a hole in my leg’; the idea of writing as suture, accident, lacing or fold; the idea of writing without mastery, writing as a ‘having died away’ from the object of longing. Speech as a muted potential. It is so easy to misread ‘wound’ for ‘world’, and in so doing to rethink what we mean by ‘quiet’, which is not so much the absence of content in poetry as the pink noise that suffuses and interferes with it.

> Pink noise being the sparkling conditions for poetry as disruptor of reception, perception and comprehension. Peter Riley summarises Graham’s work as ‘a challenge to transmission’, where often ‘sound and vision seem to rule over everything else the poem might bear’. ‘I’m up here / eyes closed’, Lesley Harrison writes in ‘Waiting for the Ferry, Rousay’, an open-field poem formed by self-erasure of the prose-poetic paragraph presented opposite: a process bearing within itself the work of the trace, the stitch, the thread, the bleed into clarity or ‘mist’. In the blank space of Harrison’s poem, we find a walk or a moving plume of breeze and meaning, the act of choosing to abandon or keep, conceal or state. Riley again: ‘the condition of writing, or writing poetry, is itself the total embodiment of this paradoxical theatre of action and suspension’ — the here, the before, the fugitive time between. It is the work of ‘exchange’ that Riley deems the ‘worth’ of Graham’s constructed spaces, those points of meaning’s refusal which ‘cast the poem out into the world’. Try To Be Better happily clutches the yellow highlighter and captures those points of exchange as its swirling raison d'être. Reading, I find myself drawing internal lines and loops, much like the concrete poetics of Lucy Mercer’s ‘Nightdial’.

> What does it mean to think about writing from a ‘hole’ that is not necessarily the mouth, the origin of speech as an act of interpersonal immediacy? To think about writing as the semiotic play between blurs and lines? What other ‘streams’ might we begin to conceptualise in relation to poetry? ‘I / I am / I am practising / I am practising myself’, unfolds Nick Thurston’s ‘How To Speak Myself Out of Myself’. I think of Jane Goldman’s poems, the recurrent, reflexively-disclosing echo of the ‘i-i’. The iterative act of self-reveal as something deferred and material, standing facing the sea to say ‘Here I am’, the horizon of yourself expanding and receding. To speak is a spatial affair:

I know about unkempt places

Flying toward me when I am getting ready

To pull myself together and plot the place

To speak from.

(Graham, ‘Language Ah Now You Have Me’)

What is this knowledge of the wild and myriad that flies towards the subject preparing to speak? An epistemology of mess and tendency, of threads being pulled and lines being drawn: the spatial work of a weave and plot. It is not about the speech, the content, so much as the conditions for speaking, the place spoken from which is freed from person to something more like a texture and geometry of surface. I could write about the declarative strokes of Marianne Røthe Arnesen’s ‘Skelp’ and ‘Pane’, their holding of thickly gooey ochres and cerulean blues against scratchier blacks, peaches and greens. The figurative is replaced by the affective structuring of intensity and gesture, emotive hues held against pale skin tones, the warm and cool in play. I could write about the use of diacritics and experimental punctuation throughout the collection, most notably in Astrid Alben and Zigmunds Lapsa’s ‘Dead Little Rabit’ sequence, where slashes, brackets and asterisks abound, pushing beyond language into the terrain of ‘signal’. A terrain of trauma (‘Like the voice of a loved one who has died / that speaks to us in inaudible consonants’) and wandering beyond human expression, with ‘bioluminescent tendrils bloom[ing]’. I think of Dorothea Lasky’s practice of what Robert Dewhurst calls ‘wild lyric impersonation’, and see hints of it all over this text, shimmering and blinking with ‘insect noises’, colours, interruptions, mirror writing (Oliver Griffin’s ‘This Is The Moment’), conjunctives, glitches. Although Lasky’s veering, deadpan brilliance might seem oddkin to Graham’s more measured, though no-less disclocating, elliptical and often ‘onwards-rushing’, as Peter Riley describes, the affinity lies in that commitment to performance, openness and the smouldering, transformative holding of moments between pain and relief: ‘ingrained / pasts, scarred-cream hazards’ (Denise Riley, ‘A Thing in a Room’).

> I could write and write about Try To Be Better and still there would be so much to write about. I keep looking for metaphors to try to describe it: even the humble work of review plugs us into this ethics of the ‘try’, its self-regenerative aesthetics. Try To Be Better: in its slim rejoinder to the traditional Yellow Pages, there’s the sense that one might traverse these pages over and over in endless unfinishing and potential transmission. To ‘complete’ the reading would miss the point. What we need is something more like a swim or a bleed or stream, a brushing back and forth, a stitch [in time]: a reading within the ‘gash of language’ (Daisy Lafarge, ‘Notes Toward an Erotics of Wading’). Oliver Griffin’s ‘This Is The Moment…’ shows nine photographs of wristwatches worn by ‘my personal friendship circle’: ‘A collection of horology’. Perhaps we might read this work as mise en abyme for the poetry, essays and art of Try To Be Better: a holding of simultaneous interpretations whose moments of encounter lag and defer, push us here and there, click and collect but somehow also flash at once. A horology of Graham’s work, which itself bears the study and measurement of time. Creative response as temporal gesture, a leap, flip or fold backwards and into the future — an existential drama of writing as movement and immersion itself, which leads us, ideally, as the collection does in its final line, ‘right into Hope Street’ (Thomas A. Clark, ‘To W. S. Graham’).

~

Try To Be Better is out now and available to purchase here, from Prototype Press.

~

Text: Maria Sledmere

Published 22/9/19

#poetry review#reviews#review#poetry#Sam Buchan-Watts#Lavinia Singer#W. S. Graham#Greenock#Maria Sledmere#Prototype Press

0 notes

Text

4 Innovative Ways to Co-Author a Book

Everyone wants to write a book — right? Studies show that 74% of people think they have a book in them. Teens are no exception. With the ease in which that can be done, thanks to word processors like Word and Docs, online editors like Grammarly, and automated publishers like Kindle, there’s no reason why teens can’t do just that. Look at this list of kids who wrote successful books in their teens — or in one case, before:

Alexandra Adornetto — published The Shadow Thief at age 14 and Halo at 18.

Christopher Paolini — published Eragon at age 16 (he is now over 30)

Steph Bowe — published Girl Saves Boy at age 16.

Cayla Kluver — published Legacy at age 16

Alec Greven — published How to Talk to Girls at age 9

As a teacher, I recognize that writing a book ticks off a range of student writing skills by providing organic practice in many required standards such as descriptive detail, well-structured event sequences, precision in words and phrases, dialogue, pacing, character development, transition words, a conclusion that follows what came before, research, and production/distribution of the finished product. I’ve tried novel-writing activities with students several times to varied results. Everyone starts out fully committed and enthusiastically engaged but by the end of the project, only the outliers on the Bell Curve finish. The rest have too much trouble balancing the demands inherent to writing a 70,000-word book (or even its shorter cousin, the novella). That I understand, as a teacher-author struggling with the same problems. As a result, usually I settle for less-impassioned but easier-accomplished pieces like short stories or essays.

Then I discovered co-authoring, a way to get all of the good achieved from writing a book without the intimidating bad. Many famous books have been co-authored, most recently, Bill Clinton and James Patterson’s The President is Missing but there’s also Neil Gaiman and Terry Pratchett’s Good Omens, Stephen King and Peter Straub’s The Talisman, and Preston and Child’s Special Agent Pendergast series. Done right, co-authoring encourages not just the writing skills we talked about earlier but perspective-taking, collaboration, and the teamwork skills that have become de rigueur in education.

The most common approach to co-authoring a book is to have students write alternate chapters but this doesn’t work for everyone. Today, I want to talk about four alternative co-authoring approaches that allow students to differentiate for their unique needs:

vignettes

multiple POV

themed collections

comics

Vignettes

A vignette is a verbal sketch, a brief essay, or a carefully crafted short work of fiction or nonfiction based around a setting, an atmosphere, or the same characters. Typically, it is about eight hundred words but can be shorter. While it can be to one writing piece, in most cases, these are published in collections that are character-driven (rather than plot-driven), located in the same location but with different story goals, or another variance that includes the same setting/atmosphere/characters. Well-known vignettes include:

Dickens’ Sketches by Boz

Cisneros’ The House on Mango Street

Here’s how students can collaborate on a book of vignettes:

Students gather in groups interested in a specific theme, atmosphere, or character.

As a group, they write a character study of each character who will be included in the vignettes and decide on setting and atmosphere.

Individually, students write their vignette and then come together as a group to publish them.

Someone takes charge of ensuring that the ebook is formatted for the needs of the online publisher. For example, Kindle’s requirements are different than iBooks.

Multiple POVs

Multiple Point of Views (POV) make a story more interesting, more personal, and often faster-paced. For students, it’s a great way to share the work required of a novel by writing one told from multiple POVs, each student taking responsibility for telling the story through their unique POV. This instantly gives each POV character a distinct voice with its own goals and themes. Most experts suggest assigning each POV character his/her own chapter. In this way, students know roughly where they are in a plot, understand what has happened to this point and carry it forward through the eyes of their particular character.

Some excellent books written in this way are Holly Robinson’s Same But Different about a child with autism and John Green’s Will Grayson Will Grayson about two boys who share a name. A different take on multiple POVs is used by A.S. King in her YA novel, Please Ignore Vera Dietz where the multiple viewpoints are Vera Dietz at different points in her life.

A Themed Collection

A themed collection is probably the most common collaborative approach and the easiest to achieve if the class lasts only a semester. In this option, each student writes a story that is unconnected to classmate stories in every way except for the theme. For example, the theme might be Life in Colonial America or Life of an 1820’s Immigrant. Students can write a biography, a personal memory, an essay, or a fictional story as long as it revolves around the chosen theme.

To make it more challenging, students might not only share a theme but characters, a setting, or a plot.

A Comic Book

Note: While comic books and graphic novels are different writing forms, for this comic book option, either is acceptable.

Kids and adults love comic books. For some, it’s what first got them excited about reading. For others, comics like Brian Vaughan’s Paper Girls and Jarrett Krosoczka’s Hey, Kiddo are why they returned to reading after pages filled with black-and-white text lost their interest.

Co-authoring with comics as the vehicle is the easiest approach when it comes to dividing up responsibilities. Here’s how you would do that:

As a group, students collaborate on a storyline, characters, setting, rising action, climax, and timeline.

Once this is done, each student accepts responsibility for the completion of one task associated with the story such as drawing the frames, inking and coloring the images (which could be done by two students), adding the dialogue bubbles, lettering the emotion bubbles, and proofing.

Comics can be written old school — by hand — or using a digital comic program like Manga Studio Ex.

Students might select this option because they love comics but also because it’s a more social form of writing in what traditionally is a solitary exercise. Students who have avoided writing because they prefer spending time with friends may rethink that decision when given the option to write with comics.

***

Now really, aren’t these great ways students can collaborate on writing? Students, using one of these approaches, will come away with a completely different attitude about being an author.

More

Middle School lesson plan for writing an ebook

10 Great PowerPoint Changes You Probably Don’t Know About

Innovative Ways to Encourage Writing

Jacqui Murray has been teaching K-18 technology for 30 years. She is the editor/author of over a hundred tech ed resources including a K-12 technology curriculum, K-8 keyboard curriculum, K-8 Digital Citizenship curriculum. She is an adjunct professor in tech ed, Master Teacher, webmaster for four blogs, an Amazon Vine Voice reviewer, CSTA presentation reviewer, freelance journalist on tech ed topics, contributor to NEA Today and TeachHUB, and author of the tech thrillers, To Hunt a Sub and Twenty-four Days. You can find her resources at Structured Learning.

4 Innovative Ways to Co-Author a Book published first on https://medium.com/@DigitalDLCourse

0 notes

Text

4 Innovative Ways to Co-Author a Book

Everyone wants to write a book — right? Studies show that 74% of people think they have a book in them. Teens are no exception. With the ease in which that can be done, thanks to word processors like Word and Docs, online editors like Grammarly, and automated publishers like Kindle, there’s no reason why teens can’t do just that. Look at this list of kids who wrote successful books in their teens — or in one case, before:

Alexandra Adornetto — published The Shadow Thief at age 14 and Halo at 18.

Christopher Paolini — published Eragon at age 16 (he is now over 30)

Steph Bowe — published Girl Saves Boy at age 16.

Cayla Kluver — published Legacy at age 16

Alec Greven — published How to Talk to Girls at age 9

As a teacher, I recognize that writing a book ticks off a range of student writing skills by providing organic practice in many required standards such as descriptive detail, well-structured event sequences, precision in words and phrases, dialogue, pacing, character development, transition words, a conclusion that follows what came before, research, and production/distribution of the finished product. I’ve tried novel-writing activities with students several times to varied results. Everyone starts out fully committed and enthusiastically engaged but by the end of the project, only the outliers on the Bell Curve finish. The rest have too much trouble balancing the demands inherent to writing a 70,000-word book (or even its shorter cousin, the novella). That I understand, as a teacher-author struggling with the same problems. As a result, usually I settle for less-impassioned but easier-accomplished pieces like short stories or essays.

Then I discovered co-authoring, a way to get all of the good achieved from writing a book without the intimidating bad. Many famous books have been co-authored, most recently, Bill Clinton and James Patterson’s The President is Missing but there’s also Neil Gaiman and Terry Pratchett’s Good Omens, Stephen King and Peter Straub’s The Talisman, and Preston and Child’s Special Agent Pendergast series. Done right, co-authoring encourages not just the writing skills we talked about earlier but perspective-taking, collaboration, and the teamwork skills that have become de rigueur in education.

The most common approach to co-authoring a book is to have students write alternate chapters but this doesn’t work for everyone. Today, I want to talk about four alternative co-authoring approaches that allow students to differentiate for their unique needs:

vignettes

multiple POV

themed collections

comics

Vignettes

A vignette is a verbal sketch, a brief essay, or a carefully crafted short work of fiction or nonfiction based around a setting, an atmosphere, or the same characters. Typically, it is about eight hundred words but can be shorter. While it can be to one writing piece, in most cases, these are published in collections that are character-driven (rather than plot-driven), located in the same location but with different story goals, or another variance that includes the same setting/atmosphere/characters. Well-known vignettes include:

Dickens’ Sketches by Boz

Cisneros’ The House on Mango Street

Here’s how students can collaborate on a book of vignettes:

Students gather in groups interested in a specific theme, atmosphere, or character.

As a group, they write a character study of each character who will be included in the vignettes and decide on setting and atmosphere.

Individually, students write their vignette and then come together as a group to publish them.

Someone takes charge of ensuring that the ebook is formatted for the needs of the online publisher. For example, Kindle’s requirements are different than iBooks.

Multiple POVs

Multiple Point of Views (POV) make a story more interesting, more personal, and often faster-paced. For students, it’s a great way to share the work required of a novel by writing one told from multiple POVs, each student taking responsibility for telling the story through their unique POV. This instantly gives each POV character a distinct voice with its own goals and themes. Most experts suggest assigning each POV character his/her own chapter. In this way, students know roughly where they are in a plot, understand what has happened to this point and carry it forward through the eyes of their particular character.

Some excellent books written in this way are Holly Robinson’s Same But Different about a child with autism and John Green’s Will Grayson Will Grayson about two boys who share a name. A different take on multiple POVs is used by A.S. King in her YA novel, Please Ignore Vera Dietz where the multiple viewpoints are Vera Dietz at different points in her life.

A Themed Collection

A themed collection is probably the most common collaborative approach and the easiest to achieve if the class lasts only a semester. In this option, each student writes a story that is unconnected to classmate stories in every way except for the theme. For example, the theme might be Life in Colonial America or Life of an 1820’s Immigrant. Students can write a biography, a personal memory, an essay, or a fictional story as long as it revolves around the chosen theme.

To make it more challenging, students might not only share a theme but characters, a setting, or a plot.

A Comic Book

Note: While comic books and graphic novels are different writing forms, for this comic book option, either is acceptable.

Kids and adults love comic books. For some, it’s what first got them excited about reading. For others, comics like Brian Vaughan’s Paper Girls and Jarrett Krosoczka’s Hey, Kiddo are why they returned to reading after pages filled with black-and-white text lost their interest.

Co-authoring with comics as the vehicle is the easiest approach when it comes to dividing up responsibilities. Here’s how you would do that:

As a group, students collaborate on a storyline, characters, setting, rising action, climax, and timeline.

Once this is done, each student accepts responsibility for the completion of one task associated with the story such as drawing the frames, inking and coloring the images (which could be done by two students), adding the dialogue bubbles, lettering the emotion bubbles, and proofing.

Comics can be written old school — by hand — or using a digital comic program like Manga Studio Ex.

Students might select this option because they love comics but also because it’s a more social form of writing in what traditionally is a solitary exercise. Students who have avoided writing because they prefer spending time with friends may rethink that decision when given the option to write with comics.

***

Now really, aren’t these great ways students can collaborate on writing? Students, using one of these approaches, will come away with a completely different attitude about being an author.

More

Middle School lesson plan for writing an ebook

10 Great PowerPoint Changes You Probably Don’t Know About

Innovative Ways to Encourage Writing

Jacqui Murray has been teaching K-18 technology for 30 years. She is the editor/author of over a hundred tech ed resources including a K-12 technology curriculum, K-8 keyboard curriculum, K-8 Digital Citizenship curriculum. She is an adjunct professor in tech ed, Master Teacher, webmaster for four blogs, an Amazon Vine Voice reviewer, CSTA presentation reviewer, freelance journalist on tech ed topics, contributor to NEA Today and TeachHUB, and author of the tech thrillers, To Hunt a Sub and Twenty-four Days. You can find her resources at Structured Learning.

4 Innovative Ways to Co-Author a Book published first on https://medium.com/@DLBusinessNow

0 notes

Text

1/9/18

WRITER OF THE WEEK Born on January 7th, Zora Neale Hurston was an African-American anthropologist, folklorist, and novelist in the first half of the 20th century. The library has several of her works, both fiction and nonfiction, including her best known, Their Eyes Were Watching God.

SOCIAL HOUR Warm up at Social Hour this Wednesday the 10th at 2 PM. We’ll have coffee and treats – you bring the conversation.

CRAFT Join us for our adult crafting session this Thursday the 11th at 2 PM. Our project this month is a candleholder to light you through to Spring.

REGULAR PROGRAMS Music and Movement for toddlers is Tuesday at 10 AM. Story Time for ages 3 – 6, with picture books and crafts, is on Wednesday and Saturday at 10:30 AM. Call the library or check out our website for all the details on all of our upcoming events.

LIBRARY CLOSED The library will be closed next Monday, the 15th, in honor of Martin Luther King, Jr. Day.

JUST ARRIVED Bring your child in to check out some of our newest chapter books. Two are rather spooky. In The Haunted House Next Door, a ghost hunter named Desmond Cole investigates the house of his new friend Andres, and in Oddity a girl starts taking a new look at just how weird her New Mexican hometown is. Another girl faces more down to earth troubles – like learning to stand up for herself – in In the Country of Queens, while a boy faces down the struggles that come with moving to a new place and figuring out who your friends are in Once Upon a Winter. Lastly, in the more whimsical The Crims, in order to get back into her private school a girl must prove that her proudly criminal family didn’t actually pull off the crime for which they’re most famous. New young adult fiction sees a boy dealing with grief over his mother’s death in Ready to Fall, another facing his the loss of his sister in Munro vs the Coyote, two girls facing a mysterious danger in The Truth Beneath the Lies, and a group of Native American teens running from government threats in an apocalyptic Canada in The Marrow Thieves. In fantasy, Philip Pullman returns to the world of The Golden Compass with the start of a new series – The Book of Dust: La Belle Sauvage.

We welcome your QUESTIONS, COMMENTS, CONCERNS, PURCHASE REQUESTS, AND PROGRAMMING IDEAS. Contact us at 312 Washington Street, [email protected], 315-393-4325, or through any of our social media sites (you can do a search for Ogdensburg Public Library or find the links on our website, ogdlib.org.)

REGULAR HOURS are 9 AM to 8 PM Monday, Tuesday, and Thursday, 9 AM to 5 PM on Wednesday and Friday, and 9 AM – 3 PM on Saturday. We look forward to hearing from you and seeing you at your library!

0 notes

Text

Children’s Literary Agents Roundup: How to Write for Young Audiences

Four agents who represent children’s literature, took time out of their busy day to share their insight and wisdom on platform, writing picture books, and writing for young audiences. If you want a better understand of what these agents are seeking in their submissions inbox and in their clients—and thus developing a better understanding of how to approach them and find representation—be sure to pick up a copy of Children’s Writer’s & Illustrator’s Market 2018 for the full roundup!

Kerrie Flanagan is an author, writing consultant, publisher, and accomplished freelance writer with more than 18 years’ experience. Her work has appeared in publications such as Writer’s Digest, Alaska Magazine, The Writer, and six Chicken Soup for the Soul books. She is the author of seven books, including two children’s books, Claire’s Christmas Catastrophe and Claire’s Unbearable Campout, all published under her label, Hot Chocolate Press. She was the founder and former director of Northern Colorado Writers and now does individual consulting with writers. Her background in teaching and enjoyment of helping writers has led her to present at writing conferences across the country, including the Writer’s Digest Annual Conference, the Willamette Writer’s Conference, and the Writer’s Digest Novel Writing Conference. You can find her online at www.hotchocolatepress.com and on Twitter at @Kerrie_Flanagan. Her book, Writer’s Digest Guide to Magazine Article Writing, will release with Writer’s Digest Books in Spring 2018.

Meet the Agents

Kelly Sonnack (Andrea Brown Literary Agency) represents illustrators and writers for all age groups within children’s literature: picture books, middle grade, chapter book, young adult, and graphic novels. Kelly is on the Advisory Board and faculty for UCSD’s certificate in Writing and Illustrating for Children, and is a frequent speaker at conferences, including SCBWI’s national and regional conferences, and can be found talking about all things children’s books on Facebook (/agentsonnack) and Twitter (@KSonnack).

John Rudolph’s (Dystel, Goderich & Bourret LLC) list started out as mostly children’s books, it has evolved to the point where it is now half adult, half children’s authors—and he’s looking to maintain that balance. On the children’s side, John is keenly interested in middle-grade and young adult fiction and would love to find the next great picture book author/illustrator.

Sara Megibow (KT Literary) is a literary agent with nine years of experience in publishing. Sara specializes in working with authors in middle grade, young adult, romance, erotica, science fiction, and fantasy. She represents New York Times bestselling authors, Roni Loren and Jason Hough, and international best-selling authors, Stefan Bachmann and Tiffany Reisz. Sara is LGBTQ-friendly and presents regularly at SCBWI and RWA events around the country. She tries to answer professional questions on Twitter (@SaraMegibow) as time allows.

Jennifer March Soloway (Andrea Brown Literary Agency) represents authors and illustrators of picture book, middle grade, and YA stories, and is actively building her list. For picture books, she is drawn to a wide range of stories from silly to sweet, but she always appreciates a strong dose of humor and some kind of surprise at the end. When it comes to middle grade, she likes all kinds of genres, including adventures, mysteries, spooky-but-not-too-scary ghost stories, humor, realistic contemporary, and fantasy. Jennifer regularly presents at writing conferences all over the country, including the San Francisco Writers Conference, the Northern Colorado Writers Conference, and regional SCBWI conferences. For her latest conference schedule, craft tips, and more, follow Jennifer on Twitter at @marchsoloway.

What is the biggest mistake adult writers make when writing for young audiences (up through middle grade)?

Sonnack: Sounding like they’ve been listening in on their kids’ conversations. It’s really obvious when a writer approaches a story because they want to teach their kids a lesson versus really remembering what it was like to be that age and writing from a kid’s perspective.

Rudolph: Likewise, misunderstanding the proposed genre. For picture books, that could mean a text that’s way too long, vocabulary and sentence structure way above age level, or adult characters without any kid appeal. Chapter books and middle grade are more flexible, but I still turn down a lot of those projects where the voice and characters are too advanced—or too young.

Megibow: Great question! In my opinion, the biggest mistake adult writers make when writing for young readers is they use a narrative voice that sounds like an adult writing for a child. Young readers demand authentic books! Some adult writers “talk down” to young audiences by using silly language or by not fleshing out complex conflicts or characters. Avoid these mistakes! Write complex characters, real conflict, and always use an authentic voice.

Soloway: Crafting a voice that sounds adult instead of having the perspective of a child.

There is lots of talk at conferences and in writing magazines about platform. How important is it to you that a writer has an established platform?

Sonnack: Platform is something that means a lot more for the adult nonfiction market where readers are looking for advice/information from an established source (say, you want a book about finance—you’re probably going to want to buy a book written by someone who has some expertise in that field). In nonfiction for kids, this can be important too, but for kids’ fiction, your readers don’t really care who you are. This really only comes into play when an author has been successful and established a fan base. At that point, the child reader may follow the writer and want to read their next book(s).

Instead of platform, I like to see market awareness and engagement with the kid lit community. These things indicate that a prospective writer is more prepared for a career as a writer/illustrator. And that they’re giving back and participating in the community we hope will support them once they publish.

Rudolph: I don’t think platform is as important in children’s books, or at least not at the point when I sign a client. I do like to see authors engage with the world, whether through social media, being a member of SCBWI, or writing in other genres. But that’s very much secondary to the quality of the work. Once a client is signed, though, I do ask them to work on all of those things, and continue that work once their book is sold.

Megibow: For a debut fiction writer, I’m not worried about platform at the point I read a query letter. Some writers query with no platform at all and some come to the slush pile with an extensive social media campaign already in place. Both of these writers’ manuscripts will be reviewed equally. If a writer has an author website at the point they submit, I like to see that in the query letter—but it’s not a deal-maker or a deal-breaker. If we go on to work together, there is time to build platform and branding after we get a book deal.

A smart platform is important to have in place once the publishing house starts shopping a novel to its retailers and once the agent starts shopping subsidiary rights, but that platform should be tailored to the author’s personality and the genre in which they write. These are things that can be done after the query phase.

Soloway: For me, a platform is less important than the quality of the writing and story, but good platforms never hurt!

Grab the latest edition of Children’s Writer’s

& Illustrator’s Market online at a discount!

Because picture books are short, some writers think they are easy to write. What is the biggest mistake writers make when writing for this market and what makes a great picture book?

Sonnack: I think they’re one of the hardest forms to execute, especially for new writers. Many writers don’t take the time to explore the current landscape of picture books and what is succeeding today (which is quite different than when they were a picture book reader). They also often think the illustrations need to be a part of the submission package (which isn’t true; the publisher usually selects an illustrator once they purchase the text). I also see a lot of manuscripts that aren’t full stories (with a beginning, middle, and end, including conflict and resolution), or that aren’t doing anything special with the writing.

Rudolph: I don’t know if this is the biggest mistake, but not telling a story is up there. I get a ton of picture book manuscripts that aren’t stories—they’re glorified lists or concept books or poems—and I pass on almost all of them. Want to write a great picture book? Tell a great story!

Soloway: The best picture books have wonderful language at the line level that is fun to read aloud, a full story arc, a full character arc, an additional story thread, and an unexpected twist at the end that is either funny or sweet or both—and all of that needs to happen in 500 words or less. It’s quite a task, and the people who write great picture books are masters at their craft!

If you’re an agent looking to update your information or an author interested in contributing to the GLA blog or the next edition of the book, contact Writer’s Digest Books Managing Editor Cris Freese at [email protected].

The post Children’s Literary Agents Roundup: How to Write for Young Audiences appeared first on WritersDigest.com.

from Writing Editor Blogs – WritersDigest.com http://www.writersdigest.com/editor-blogs/guide-to-literary-agents/middle-grade-literary-agents/childrens-literary-agents-write-ya-mg-audience

0 notes