Text

Este domingo 6 escaramuzas por campeonato estatal charro de Tlaxcala 2024

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

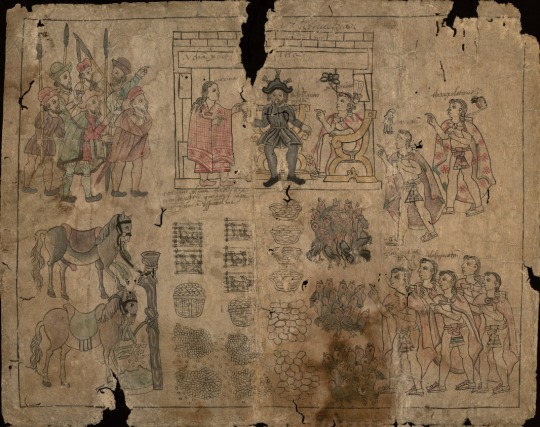

Lienzo de Tlaxcala, 1560 65 x 26,5 cm Desenho policromado sobre papel de casca de árvore relata a história do encontro dos Tlaxcallans e Castelhanos e sua aliança contra os Mexica em 1521

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fragmento del Lienzo Tlaxcala en el que se muestran los alimentos que se otorgaron a las tropas de Hernán Cortés: guajolotes, huevos, codornices, maíz y tortillas

ca. 1530

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Lote:201 Virgen de Guadalupe con Donantes por Pelagio Antonio de Labastida y Dávalos (Zamora, Michoacán; 21 de marzo de 1816-Yautepec, Morelos; 4 de febrero de 1891), escuela Mexicana del siglo XIX Óleo sobre lienzo de notable interés histórico-artístico para el patrimonio cultural mexicano, medidas: 90 x 72,5 cm. Posible encargo privado devocional realizado y firmado por Don Pelagio Antonio de Labastida y Dávalos en sus tiempos de sacerdote (Zamora, Michoacán; 21 de marzo de 1816-Yautepec, Estado de Morelos; 4 de febrero de 1891) fue un sacerdote, abogado y doctor en cánones. Estudió en el Seminario Conciliar de Morelia, del que más tarde fue profesor y rector. Se ordenó en 1839. Fue prebendado, canónigo y gobernador de la mitra de Morelia y en julio de 1855 se le designó obispo de Puebla. En diciembre siguiente estalló la insurrección de Antonio de Haro y Tamariz, al grito de Religión y Fueros. Derrotada ésta, el gobierno comprobó que los medios financieros fueron sumininstardos por la Mitra poblana y ordenó que los bienes del Obispado de Puebla en esa entidad, en Tlaxcala y en Veracruz, fueran confiscados y vendidos. Labastida se opuso a ello, en consecuencia fue desterrado en 1856. El diario El Heraldo publicó que Labastida dijo durante un sermón: "..con bastante dolor veo que el pueblo cristiano mira con desprecio que se atente contra los bienes eclesiásticos..". El gobierno ordenó su destierro, el general Mariano Morett lo escoltó a Veracruz. El 20 de mayo zarpó con dirección a Roma, haciendo escala en La Habana durante quince días. Desde ahí emitió un comunicado al ministro de Justicia, en el cual expresó su queja por la forma tan repentina de actuar del gobierno mexicano y negó haber pronunciado las palabras que se le atribuyeron. #templumfineartauctions #templum #auctioneer #auctions #subastasbarcelona #barcelonacity #barcelonabeach #masterpiece #decoración #antikviteti #antiquesitalian #artstagram #eixample #antiquariato #barcelona #colonial #colonialart #escuelacolonial #colonialschool #oldmasterpaintings #colonialantiques #guadalupe (en Barcelona, Spain) https://www.instagram.com/p/Cow_DB3INEX/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#templumfineartauctions#templum#auctioneer#auctions#subastasbarcelona#barcelonacity#barcelonabeach#masterpiece#decoración#antikviteti#antiquesitalian#artstagram#eixample#antiquariato#barcelona#colonial#colonialart#escuelacolonial#colonialschool#oldmasterpaintings#colonialantiques#guadalupe

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Una imagen del Lienzo de Tlaxcala, México, en el cual aparece el conquistador nuevo español tlaxcalteca Chichimecatecle, que se traduce como el Gran Señor Chichimeca, quién es junto con Masse-Escaci uno de los conquistadores nuevo españoles más olvidados de la historia de España. En mi libro El Caminar del Sol podrás conocer su historia. Cómpralo entrando en este enlace: https://chicosanchez.com/blog/f/el-caminar-del-sol-un-libro-de-chico-s%C3%A1nchez?blogcategory=Libros

0 notes

Text

recinto ferial tlaxcala 2018 CompartirCentro de Convenciones, CompartirLienzo Charro, Compartirkiosko, Compartirrecinto ferial, Feria Tlaxcala, JorgeLuisVH, Lienzo Charro, kiosko, letrero, letrero de ciudad, placa conmemorativa, recinto ferial

0 notes

Text

INICIÓ LA EXPOSICIÓN “PINTAR EL LIENZO DE TLAXCALA”

INICIÓ LA EXPOSICIÓN “PINTAR EL LIENZO DE TLAXCALA”

#PintarLienzoDeTlaxcala#Cultura#OMG Es un proyecto artístico e histórico que busca generar una visión del pueblo tlaxcalteca y su participación en la conquista El gobierno del estado a través de la Oficialía Mayor de Gobierno (OMG), la Secretaría de Cultura (SC) y el Archivo Histórico del Estado de Tlaxcala (AHET), inauguró la exposición “Pintar El Lienzo de Tlaxcala”, en el Museo de la…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

Lienzo de Tlaxcala / History of Tlaxcala: it is an illustrated codex produced in the second half of the sixteenth century, at the request of the town council of Tlaxcala. The manuscript highlights the religious, cultural, and military history of the Tlaxcaltec people. The aim of this type of documents was to claim favours and honours from the king, by means of highlighting the alliance and friendship with the Spaniards, as well as the military victories and prominance of the indigenous froces in the process of conquering the different territories. The Tlaxcaltec people were one of the indigenous people of America that were most favoured by the imperial elites, being privileged and elevated to the status of european nobility.

LAW XXXIX

D. Felipe II in Poblete on April 16, and in Zaragoza on March 25, 1585. That the viceroys of New Spain honour and favour the Indians of Tlaxcala and their city and republic.

“Considering that the Indians of Tlaxcala were the first to receive the Holy Catholic Faith in New Spain, and they gave us obedience, and since the viceroys call them for burials, honours, and funerals of princes, reviews, aid and assitance in the needs that arise, and other public acts: It is our will, and we command the viceroys, that they have particular care to honour and favour them, and to call them on the occasions of our real service, and that they shall take much care of their city and republic, so that others may see the mercy we give them and serve us with the same fidelity”.

“A documented fact is that the Spaniards considered them [tlaxcaltecas] as allies in the conquest of the Mexica Empire. The Royal Decree of the Emperor Charles V in February 1537, in addition to calling the Tlaxcalteca "cousins” of his [the Emperor] (exclusive protocolar prerogative for the Spanish high nobility), praises their loyalty and tenacy to Cortés. It is a historical fact that the totality of the Tlaxcalan population was elevated to blood nobility (hidalguía) as a reward for their merits and services, as befits conquistadors" (Corona Páez, 2002)

For whatever reason the image appears blurry, but when accessing through my tumblr it improves a lot, it can also be enlarged.

#mexico#tlaxcala#history#spain#tlaxcaltecas#historia#españa#america#lienzo de tlaxcala#tlaxcalan codex#sorry for the shitty translations

17 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Rout of La Note Triste from the Lienzo de Tlaxcala

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

TONALLAN TLATOHCAYOTL. “Todo cabe en un jarrito sabiéndolo acomodar”. Antiguo dicho popular tonalteca🗣

Hablar de Tonalá,vocablo de origen náhuatl y cuyo significado al español castellano fue establecido en la crónica del Gallego Fray Antonio Tello.

Tello, miembro de la orden franciscana venido a las tierras de la Nueva Galicia donde desempeñaría el cargo como “guardián” de la orden y que le permitirá conocer de primera mano sobre los hechos, acontecimientos y personajes que participaron literalmente “a sangre y fuego” durante la conquista del territorio, luego de la caída del reino de Michoacán.

En el año de 1652; fray Antonio Tello se vuelve célebre e indispensable para conocer nuestra historia al publicar su "Crónica Miscelánea de la Conquista de la Nueva Galicia".

En particular sobreTonalá; detalla como los nahuatlatlos o traductores tlaxcaltecas que acompañaban al Conquistador Nuño de Guzmán, reconocieron el lugar como "Tonallan", interpretado como: "Lugar por donde el Sol Sale". Quizá la frase que más podría acercarse a este aforismo,sería Tonaya o Tonalla que literalmente nos habla del “Amanecer”.

El sapientísimo D. José María Arreola, miembro del Instituto Jalisciense de Antropología e Historia, en su obra "Nombres Indígenas de lugares del Estado de Jalisco, estudio etimológico ", pag. 31, nos dice al respecto lo siguiente: Tonalá, Tonallan-Tonalla, tonallan y tonallo, son nombres que significan lo relativo al sol, que en mexicano clásico se dice tonatiuh, y por estos rumbos tonali o tonati; Tonalá como nombre de lugar significa: Lugar que está dedicado al culto del sol. El nombre se refiere tanto al antiguo reino, que opuso resistencia a la conquista ibérica, como su capital.

El nombre procede al origen, según el mito náhuatl que describe el sacrificio de los dioses dando origen a la creación del Sol y la Luna, establecido en Teotihuacán como parte de los mitos establecidos. Es el caso para Tonalá, el cual contiene elementos que vale la pena considerar: el glifo de identificación y la existencia de una piedra dedicada al culto solar.

Primeramente diremos que el glifo establecido aparece en la lámina de la tira de la peregrinación del códice Aubin, fijando la fecha de llegada a estas tierras en el año 1111 de nuestra era, con la demarcación de un círculo mayor y cuatro pequeños círculos, pag. 6, México a Través de los Siglos, tomó II. Coincidentemente la imagen sorprende con la piedra del Sol actual, ubicada en la cima del Xictepetl o del ombligo.

Fue don Alfonso Caso quien denominó a los Aztecas como " El pueblo del Sol", teniendo por deidad a Tonatiuh, cuyo significado literal nos dice:"el que se ilumina a sí mismo", cuyo representante es Huitzilopochtli (Señor de lo criado), tenido por dios principal entre cocas y tecuexes, los pobladores originales del Valle de Tonallan. Según esta cosmogonia, era el oriente La Casa del Sol, siempre representado con puntos en forma de quincunce o distribuidos uniformemente, cuyos colores, rojo (sangre), y amarillo (calor, vitalidad) se estableció en el característico lienzo de Tlaxcala, elaborado por Diego Muñoz Camargo a mediados del siglo XVI, representando la escena del momento de la conquista del lugar.

Finalizó citando el capitulo que dedica Fray Diego Duràn en referencia al culto solar: "De la fiesta que al Sol se hacía bajo este nombre, Nahuolin, donde se refiere a una orden de guerreros compuesta exclusivamente por individuos de la nobleza que tenían por dios y caudillo al Sol. Quienes llevaban a cabo la festividad dos veces en el año... La primera el 17 de marzo y la segunda a dos días del mes de diciembre "."Se cumple para nosotros un destino emocionante y misterioso: escrito para la gloria de los vencidos y no para el provecho de los vencedores ".

Cariacha (hasta la próxima).

En la imagen. “Tótem” con la palabra Tonalá. Costado sur poniente. Plaza Cihualpilli. Tonalá.

#soydetonala®🌞

#tierradenahuales👹 @XDondeelSolSale

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Quedan 29 días para que de inicio el Estatal charro 45 de Tlaxcala

View On WordPress

#Campeonato Nacional Charro#Charrería#Federación Mexicana de Charrería#Lienzo Charro#Tlaxcala#TlaxcalaSiExiste

0 notes

Photo

Wenaaaaaaas~ Hoy les vengo presentando a la bella Quiahuiztlán, el último barrio de los 4 señoríos que formaban “la república de..” Tlaxcallan (antiguo nombre de Tlaxcala). -Conocido como el último barrio de los 4 señoríos de Tlaxcallan que se fundó a finales del siglo XIV por un grupo de teochichimecas provenientes de Tulancingo y Huauchinango a quienes se les había prometido tierras para que se establecieran en Tlaxcallan. Por lo que sería como la prima hermana de Tlaxcala. [?] -Su nombre significa “Lugar de la lluvia”. -Es conocido como el barrio de los artesanos. - Participó en numerosas batallas luego del gran bloqueo, pesé que era buena con el macuahuitl participó mayormente como arquera, no solo por gusto sino también como una estrategia para evitarle daños o heridas severas. -Su señorío fue el que más apareció en las representaciones de las guerras de conquista en el Lienzo de Tlaxcala. -Les dejó una foto clara de su emblema q(≧▽≦q):

142 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Diego Muñoz Camargo, Lienzo de Tlaxcala: Xicoténcatl y Hernán Cortés

1 note

·

View note

Text

my university is so well stocked with rare colonial era spanish books about conquest, and holy shit they even have a khipu! i would kill to be able to spend some time in the library just spending a summer afternoon leisurely reading some of them, but of course everything is closed. reading these books is so unlike reading a modern book. it’s practically a work of art. they were so expensive to commission and the average person would never own one, they would sit in a monastery library or for use of the king or the courts. the paper is thick, the books are not a standard size (they can be enormous or small), and they are full of these rich illustrations and my favorite type of art which is engravings/etchings. i was working with this old book that opened with this stunning piece of etching art of hernan cortes “delivering” the new world to charles V... it’s incredible what you can learn about how the conquistadors perceived themselves and perceived the world. but then of course you get the indigenous perceptions through lienzos like the lienzo de tlaxcala, the art of the florentine codex, etc. it’s all so exciting!

7 notes

·

View notes

Link

@askhistorians

From /u/400-rabbits

This is a whole pack of questions so I'm going to break them up into 4 part, starting with the question of indigenous sources, then moving onto the questions of technology and warfare before looping back around to discuss how the Aztecs portrayed themselves in indigenous sources.

Indigenous Sources

There are a number of pictorial codices which compile various aspects of Aztec culture, with the Borgia group codices thought to represent either a pre- or peri-Hispanic corpus. These pictorial documents are heavy on religious/calendric imagery though, and often bereft of written glosses, which makes them a difficulty entry into Aztec history.

More accessible are alphabetic histories written in the early Colonial period by indigenous and mestizo authors, as well as Spanish friars. The General History of the Things of New Spain, for instance, is a 12 volume encyclopedic collection of topics ranging from the creation of the world to which plant has berries good for treating dandruff. More commonly known as the Florentine Codex, after the most complete copy of the manuscript, the work was compiled in starting the late 1540s by a Spanish friar, Bernardino de Sahagún, utilizing Nahuatl scribes educated at the Colegio de Santa Cruz de Tlatelolco. The resulting work is composed in Nahuatl with Spanish translations (though sometimes just summaries). The entirety of the work was translated into English in the mid-20th century by Anderson and Dibble.

Diego Durán was Dominican Friar who wrote a history of the indigenous people he lived and preached among. In the 1570s he wrote The Book of Gods and Rites and The Ancient Calendar, both of which have been translated into English by Heyden and Horcasitas. His magnum opus, however, is his Historia de las Indias de Nueva España y Islas de Tierra Firme which is significant not only as an early European-style narrative history of the Mexica people, but also as a text based upon a proposed earlier source known as Crónica X (though arguments exist as to whether this was a single source or a diverse corpus of earlier works).

Other Crónica X sources include the work of another friar, this time a Jesuit named Juan de Tovar, who was a contemporary and cousin of Durán. Indeed, he probably even used Durán's work in his own writings, which survive as the Tovar Manuscript and Ramirez Codex (though the latter is a copy not directly attributed to Tovar). As with Sahagún and Durán, Tovar's writings were suppressed and almost lost until rediscovery in the 19th Century, although his fellow Jesuit, José de Acosta, relied heavily on Tovar's work in the chapters covering Mexico in his Natural and Moral History of the Indies.

The other Crónica X work comes from Fernando Alvarado Tezozomoc, who was a descendant of the ruling dynasty of Tenochtitlan born shortly after the Conquest. Also writing in the latter part of the 16th Century, his significant work is the Spanish language history of the Mexica, the Crónica Mexicana. Certain scholars, notably Galvaro Romero, have gone further and proposed Tezozomoc was the actual author of the Crónica X, though this is a minority view. A later work in Nahuatl, the Cronica Mexicayotl, covers almost the exactly same material, but was physically written by another indigenous author, Don Domingo Chimalpahin. There are various takes on the authorship of the Cronica Mexicayotl, but the synthesis approach it is an adaptation of Tezozmoc's earlier work by Chimalpahin. (See Battock 2018 “La Crónica X: sus interpretaciones y propuestas” for a summary of the historiography of Crónica X). No English translation of the Cronica Mexicana (to my knowledge) exists, but Schroeder and Anderson have published a translation of Chimalpahin's writings in their (1997) Codex Chimalpahin.

Of note, the Monarquia Indiana written by Franciscan friar Juan de Torquemada can also be seen as part of the Crónica X tradition, though this early 17th Century work actually drew upon a number of sources. Torquemada's work would subsequently inform the work of the Jesuit Francisco Clavijero, who wrote his La Historia Antigua de México in the 18th Century. In a pattern you might be starting to notice, there is no full English translation of Torquemada's work (though all 6 volumes are available online via INAH).

Outside of the Crónica X tradition there are various other works, the most important to understanding the Aztecs coming from the Texcoco tradition. Fernando de Alva Cortés Ixtlilxochitl, a descendant of the ruling dynasty of that altepetl, wrote various works in the early 17th Century by drawing upon then extant pictorial works (such as the Mapa Quinatzin). Perhaps his most relevant work to this discussion is his Historia de la Nación Chichimeca. In this text, he not only outlines the various happenings of the most important polity of the eastern Basin of Mexico (and 2nd most important part of the Aztec Triple Alliance), but delves further back in history to describe the social and political rearrangements in the Basin wrought by the arrival of the Chichimecs. Alva Ixtlilxochitl, along with his relative Juan Pomar, form the much of the basis of our understanding Texcoco, though more recently there have been some critical interpretations of their histories (see Lee's The Allure of Nezahualcoyotl).

There are certainly other works produced in the decades after the Conquest which can inform our understanding of indigenous life. There are more historically minded documents written in a combination of Nahua and European styles, such as the Historia Tolteca-Chichimeca. There are pictorial documents which are more focused on genealogy and territory, like the Codex Quetzalecatzin. There are various "relaciónes," surveys conducted by the Spanish to collect demographic data (but also cultural information) about various regions. There's the compilation of Aztec tribute found in the Codex Mendoza. There are pictorial and alphabetic works about nearby regions, such as the Relación de Michoacan and the Lienzo de Tlaxcala. There are, in other words, a plethora of non-Conquistador sources to draw upon, though their accessibility and availability to an Anglophone reader maybe limited.

Technology

This is probably the most uninteresting part of your question to me, in that it falls under a "not even wrong" rubric, so apologies if this section is short and somewhat brusque. There's a whole FAQ section of past answers you can read on this topic. Suffice to say, technology and civilization are not synonymous, and neither follows a straight line of development.

The example of the wheel, for instance, is usually tritely answered by noting that Mesoamericans were aware of wheels, we see them used in toys. The next step is to note the lack of draft animals usable to haul wheeled vehicles. A further step is to note much of Mesoamerica is composed of mountains and valleys, which are less than ideal areas for wheeled carts and other conveyances (being sure to note that Andean groups had draft animals in the form of llamas, but did not utilize them to pull carts despite a well-developed road system). A further note is to look explicitly at the Basin of Mexico, whose central lake system provided more advantageous transport by watercraft than by land, though this did not preclude a system of indigenous porters, the tlamemeh.

Going with an even broader view, we might note the Aztecs were about 2500-3000 years removed from the full development of staple food crop, maize. The equivalent time period in Afro-Eurasia using wheat would put us (following Tanno and Wilcox 2006 of wheat domestication being widespread in Mesopotamia by 8500-7500 years before present) would put us in the 6th-5th Millennia BCE, which generously puts us at the very early period of polity formation in Sumeria... and centuries before we see evidence of wheeled vehicles. Certainly there was no settlement in 5th Millennium Mesopotamia which could rival the megapolis of Tenochtitlan, nor even that of Teotihuacan a thousand years earlier. Perhaps the better question is why it took so long for complex states to form in Western Asia after the adoption of agriculture, relative to Mesoamerica.

Regardless, to put things more into context, here's a relevant quote from Hopkins (1973) An Economic History of Africa:

“Although the wheel is commonly regard as a symbol of economic progress, it is as well to remember that wheeled vehicle did not achieve a decisive advantage over other forms of transport until the industrial revolution, with the development first of the railway and then of the motor car. Before that time, the use of wheeled vehicles in Europe was inhibited by many of the problems experienced in Africa. In eighteenth-century Spain, for example, pack animals, especially donkeys, were by far the most important means of transport, though ox-carts were available and were used to a certain extent. The ox-cart carried three to our times as much as a large pack animal, but since it was costly to purchase and operate, and travelled at half the speed, it could not compete with donkey transport. Wagons did not become numerous in northern Europe until the sixteenth century, and even then they were used mainly for short-haul work. Until the roads were improved, pack animals remained the leading form of long-distance commercial transport on land. 'Long trains of these faithful animals, furnished with a great variety of equipment... wended their way along the narrow roads of the time, and provided the chief means by which the exchange of commodities could be carried on.' This statement could well apply to the Western Sudan in the pre-colonial period, though in fact it refers to England in the early eighteenth century.”

Add to this that mule-trains and porters continued to be major, even primary, methods of conveyance in Mexico well into modern age. The selection of something like "the wheel" to represent "real" civilization doesn't actually reflect the realities of use, and that is just one of any number of seemingly arbitrary indicators often used to show the primitiveness of Mesoamericans. So forgive me if I don't have much patience for this question which implicitly implies that Europeans -- using wheels, metal, crops, domesticated animals, and writing they did not invent, but borrowed from other peoples -- are superior to the peoples of a region which did independently invent many of those things. Why not ask why the Spanish had not invented universal schooling, steam baths, and public waste collection?

Warfare

This is another section I’m going to only briefly touch upon, because it has been covered extensively on this forum, including another FAQ Section.

Suffice to say that the idea of the Aztecs (and Mesoamericans, in general) fighting primarily to capture and not kill is a misconception. This is not to say capturing an opponent was not a valued goal, but we must recognize that the Aztecs did not conquer a large swathe of Mesoamerica by engaging in tactics detrimental to actual winning battles. As Hassig (2016) puts it, “capture was a significant goal, although one that is perhaps overestimated in the literature.”

Isaacs (1983) proposed making a distinction between wars of conquest and Flower Wars (xochiyaoyotl) based on primary source descriptions of the former which consistently show them as having “heavy slaughter of the enemy on the battlefield.” This perspective is consistent with actual descriptions of combat from the Spanish, who routinely describe tactics which preclude taking captives, such as barrages of arrows, slingstones, and atlatl darts. Likewise, the casualty rates of their Native allies (when mentioned) are indicative of deadly nature of warfare.

Often though, wars of conquest and expansion are conflated with Flower Wars, which are often portrayed as wholly ritualistic and based upon obtaining captives for sacrifice. Hicks (1979) examines how this view does have roots in primary sources, such as when Andrés de Tapia states Motecuhzoma told him they did not conquer the Tlaxcalans because “we desire that there should always be people to sacrifice to our gods"” or when Duran has Tlacaelel declare that region to be a “marketplace where “Huitzilopochtli] will buy victims, men for him to eat.”

Even as these sources state an overt aim of obtaining sacrifice, they also acknowledge the usefulness of continuing to maintain military activity outside the normal constraints on timeframe place by the necessity to plant and harvest crops. Per Tapia, the other reason to not conquer the Tlaxcalans was to maintain a “place where our youth could train themselves,” and Duran says one benefit is “the sons of noblemen would be occupied in this way and military activity would not be lost.”

The consensus view of Flower Wars then, is that there were realpolitik aspects to Flower Wars. They allowed a powerful foe to be ground down in what was essentially a long-term siege, while wars of conquest gradually encircled them, isolating them from the rest of Mesoamerica. The Tlaxcalans themselves acknowledged this, complaining to Cortés that their conflict with the Aztecs had left them bereft of sources of cotton and salt. Hassig (1988) further notes that we see gradually intensification of Flower Wars until they shifted over to become wars of conquest, as was already starting to happen in the borderlands between Tlaxcala and the Aztecs.

Views on themselves

The central tension of the Mexica identity was that they saw themselves both as put-upon underdogs and as destined by divine providence for conquest and glory. Sahagún writes that, on their migration into the Basin of Mexico, “nowhere were they welcomed; they were cursed everywhere; they were no longer recognized. Everywhere they were told: ‘who are the uncouth people? Whence do you come?’” (Bk. 10, p.196). Yet, they were also a people who were promised greatness by their patron god, Huitzilopochtli, who said “they [would] spread out, establish ourselves, and conquer the peoples who dwell in the great world” and receive “countless, infinite, unlimited commoners who will pay tribute to you” in the form of “precious green stones, of gold, of quetzal feathers, of emerald green jade, of spondylus shells, of amethysts, of costly clothing” as well as “various kinds of feathers -- cotinga, spoonbill, trogon; all the precious feathers; and multicolored chocolate and multicolored cotton” (Chimalpahin 1997)

They were both a part of the wild Chichimec peoples, but also the inheritors of the great and refined Toltecs. They were a severe and austere people, but, as we see in the quote above, a people which valued rich and refined goods. Gradie (1994) writes about how the union between the Mexica and the Culhua merged those two heritages into a single lineage which was quintessentially dual-natured, both savage and civilized.

The Mexica were also great cultural chauvinists, particularly when it came to their language; Nahuatl pretty much means “clear speech.” As much as they saw themselves as reviled and denigrated by their neighbors, they rarely missed a chance to get their own jabs in. The Otomi, for instance, were “blockheads,” “vain,” and “greedy,” while also being “lazy, shiftless” (Bk. 10, pp. 178-9). The Matlatzinca were “presumptuous, disrespectful” people who drank too much and even though some of them spoke Nahuatl, “the way they pronounced their language made it somewhat unintelligible” (p.182). The Tlahuica, though they spoke Nahuatl and not some “barbarous tongue” were nonetheless “crude,” “pompous,” “untrained,” and “cowardly” (p. 186).

For as much as they looked down their nose at other groups, the Mexica were not hypocrites and held themselves up to the highest standards of morality, behavior, and appearance. Maffie (2013) has written extensively about how Aztec philosophy conceived of a righteous life as balancing on summit or ledge, whose slippery earth constantly threatened to drop the individual into the depths of filth and depravity. As such, the Mexica individual was to constantly being on-guard against their own flaws, constantly monitoring their own behavior, constantly striving towards fulfilling their obligations to themselves, their community, their gods.

So a “good father” is one who “exemplary; he leads a model life” by being diligent, solicitous, compassionate, sympathetic; a careful administrator of his household” (Bk. 10, p. 1). In return a “good son” is one who is “obedient, humble, gracious, grateful, reverent” (p. 2). Sahagún expounds for several chapters about the ideal behaviors of various social roles, which consistently exhort some permutations of being humble, diligent, and gracious.

So when the Aztecs speak about themselves as destined to conquer and rule, this is not simple arrogance (though yes, it is arrogance). Their destiny was not just ordained and all they had to do was wait for it to be delivered, they were expected to strive and struggle, to prove their worthiness. In the Aztec mind, they had proved themselves, and continued to prove themselves, as worthy of greatness.

Battock 2018 “La Crónica X: sus interpretaciones y propuestas” Orbis Tertius 23(27)

Duran 1994 History of the Indies of New Spain trans. Heyden

Chimalpahin 1997 Codex Chimalpahin: Society and Politics in Mexico Tenochtitlan, Tlatelolco, Texcoco, Culhuacan, and Other Nahua Altepetl in Central Mexico trans. Schroeder and Anderson

Gradie 1994 “Discovering the Chichimecas” The Americas 51(1)

Hassig 1988 Aztec Warfare

Hassig 2016 “Combat and Capture in the Aztec Empire* British Journal for Military History 3(1)

Hicks 1979 “‘Flowery War’ in Aztec History” American Ethnologist 6(1)

Isaac 1983 “Aztec Warfare: Goals and Battlefield Comportment” Ethnology 22(2)

Lee 2008 The Allure of Nezahualcoyotl

Maffie 2013 Aztec Philosophy

Sahagun 1961 General History of the Things of New Spain, Book 10: The People trans. Anderson and Dibble

Tanno and Wilcox 2006 “How fast was wild wheat domesticated?” Science 311(5769)

102 notes

·

View notes

Photo

My great grandfather many generations passed, King Xicotencotl el Viejo, born in 1425 as depicted in the Lienzo de Tlaxcala. His daughter, Doña Lucía - whom I wish there was an image of- was traded for political reasons as the common law wife of my other grandfather ancestor Pedro de Alvarado (unfortunately a horrible human being). They had the first mixtec children in the Americas, from whom I descend. This is my lineage on my father's side. #ancestors #mesoamerica #ancestry # hoodoo #conjure #rootwork #neworleansvoodoo https://www.instagram.com/p/B4Deh2WAZOi/?igshid=guybq35xn9jl

1 note

·

View note