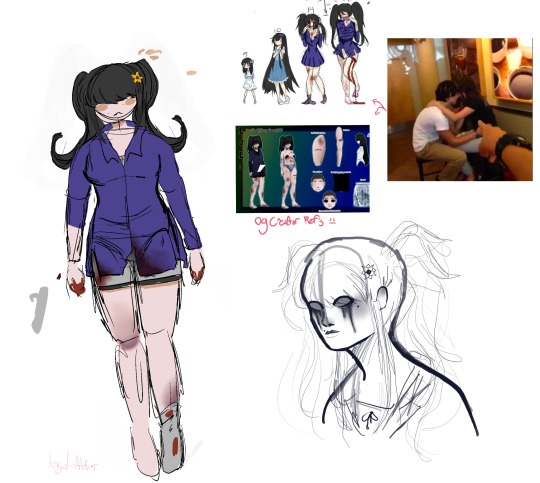

#lulu on the right is newest drawing followed by

Text

Refs and sketches with various quality for my au crypasta :p plus Mazarine

#creepypasta#my art#creepypasta fanart#crypasta#fanart#creepypasta fandom#mazarine#idk I’ll make a tage for her eventually#kate milens#lulu creepypasta#creepypasta oc#dina clark#judge angels#jane the killer#jane everlasting#jane arkensaw#jane richardson#jeff the killer#jeff woods#jeffery woods#cw blood#Kate the chaser#creepypasta kate the chaser#Lulu greatfeild#lulu on the right is newest drawing followed by#mazarine rest r a lil older

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

C. Warner-Thompson

My name is Clemy, and I am a self-published author of seven fantasy books. I have always lived in the UK, having an interest in fantasy from a young age. I love anything that is fantasy, whether that is for TV, film, or books.

I self-published my first book, 'Purest Light', when I was 16, which is the first book of my first series, 'The Sacred prophecies'. The 2nd and 3rdbooks, 'Darkest Regrets' and 'New Beginnings', were released 2 years later, allowing me to start on a second, more in-depth, fantasy series. 'The Star' was released in 2012, with its two sequels, 'The Mirage' and 'The Void', following soon after. I am now writing my newest project which consists of three books. The first being named as 'From Within the Light’, which was released in October 2016, and 'Even in the Darkest of Times' which I am due to finish by the end of this year. The third book of the series has yet to be named.

I work 5 days a week in a retail environment and writing is something I squeeze in whenever I can. Recently, I moved into my first home with my boyfriend, and we now own two crazy young cats, Rodney and Rory. I love plants; I love to watch them grow and try my hardest not to kill them, but sometimes I fail miserably. Reading and drawing were two hobbies of mine until very recently, whereas I now put all of my spare time into my current work in progress.

Thank you for this opportunity. I look forward to meeting some new readers!

Author Name: My name is C. Warner-Thompson, Clemy for short.

How long have you been writing? I started writing on my thirteenth birthday, so it’ll be 17 years in November! How time has flown!

Did you ever imagine that you would be published one day? When I first started writing I didn’t think about where I wanted to go as an author, but now I wonder whether I could get my books into shops and get out there a bit more.

What made you want to become an author? My brother pushed me into writing. He had started his first book in his teens and was self-published by 17. I loved the idea that I could follow in his footsteps. I loved films, books, games, anything that had an element of fantasy in it, and when I started writing I couldn’t stop thinking about the stories in my head.

How long have you been published? I published my first book with Lulu in 2008, but I didn’t make them available for the public until a few years after that. All these years later, I have decided to go back and rewrite my first series.

How does it feel to be published? Nothing beats the feeling of holding your own book in your hands. The feeling of pride that it gives you can never be compared.

Are you self-published or did you go through a publishing company? Why? I am self-published. I had a dream that I would get published the traditional way or get an agent to represent me, but as I grow older I don’t feel the need for that as much. I would love to be represented in the future and be able to see my books in physical shops, but I would never want to be famous in the public eyes.

How many books have you written? I am currently working on my 8thbook at the moment, which I am hoping to finish and have printed by October/ November time.

What is/are the name of your book(s)? The 8 books consist of three separate series. My first being The Sacred Prophecies, which are made up of Purest Light, Darkest Regrets and New Beginnings. My second series doesn’t have an official title, but that is made up of The Star, The Mirage and The Void. Book 7 titled, From within the Light, is the first book of three, of which I am working on book 2 at the moment

What genre is it/are they in? They are all YA fantasy, with my two newest books leaning more towards NA paranormal romance.

What do you feel will inspire others to never forget when they read your story(ies)? This is a new question to me. Many of my readers say that I am a descriptive writer so perhaps they would remember the sceneries and landscapes I describe; I also have a passion for writing detailed fight scenes which always include fantasy elements such as magic and weapons.

What's the hardest part about writing a book? Having the time to write it. People say that if you want to write then you will write, but sometimes the time needed for it just isn’t there. You may think ‘oh I have an hour spare now so I’ll write’, but it isn’t just the writing. You have to get in the right headspace. You have to reread the paragraph before to make it consistent. You have to sometimes research certain topics, and plan in depth at all times. Writing a book isn’t just about writing it.

What's the easiest part about writing a book? For me the easiest part is that I always know the ending. On each new project, I have always known the ending as soon as I have developed the characters and the story to a certain point.

Where can interested readers purchase their copy of your book(s)? All of my books are available from Lulu.com if you wanted a paperback, or if an ebook is more your thing, they are available at Smashwords.com. They are also available at Barnes and Noble, Nook and scribd, but that is for only select ones at the moment.

Do you have any future projects in the works? *Is there a tentative release date? My current WIP which I recently revealed the title for, ‘Even in the Darkest of Times’, follows on from book 7 which is set 100 years after the Fall of Angels from Grace. I am hoping for it to be finished and available for my birthday in November.

Do you have any social media sites that you would like to share with my readers? My social media journey started on Facebook, and then has progressed onto Instagram, but I also have Goodreadswhere I keep all my reviews together.

0 notes

Text

A BALKAN EDUCATION

I was pretty down on Albania in my last post. But journeying north, further from the coast, its redeeming features soon began to reveal themselves. The wilderness, dramatic beauty, political complexity and sheer “otherness” can’t fail to win you round. In fact, the entire Balkan region has woven itself firmly into our affections. In the last month we have journeyed through Albania, to Kosovo, Macedonia, Bulgaria, Serbia and finally Croatia.

My knowledge of former Yugoslavia - and the rifts and shadows cast by Europe’s last war - was sketchy to say the least. In many ways, its easy enough to ignore. The countries we have seen in the past few weeks share more similarities then differences. Driving across the many borders you see only gradual progressions in the food, landscape and slavic tongue. After a while the currencies too blend into each other, and its hard to keep track of the respective Leke, Denar, Lev, Dinar, Mark, and Kuna. The mediterranean olive oil and oranges we have become accustomed to have been supplanted by soft fruits and a diet rich in dairy. Just as one bucolic village with haystacks and higgledy-piggedly houses made from wattle and daub looks much like the next, just across the border, so too the roadside markets, bursting with cherries, strawberries, peaches, nectarines and apricots. In Kosovo we were given a guided tour of the local cuisine by a stunned supermarket shop assistant. “Why are you here?” she asked, fussing over the girls and high-5’ing them on account of their red t-shirts, emblazoned with the double-headed Albanian Eagle. Tourists are still a novelty in Europe’s newest country (whose independence was only recognised in 2008, and is still disputed by neighbouring Serbia). She followed us around the aisles, like a personal assistant, pointing out what food we should try - the best Ajvar (stewed aubergine and paprika relish), which brand of Kos (goat’s yoghurt). Yet study the war graves, etched with young men bearing kalashnikovs, the dates glaring out at you, impossibly raw and recent. Delve into any conversation in the Balkans and watch how you are immediately brought up short by an impregnable wall. We asked that same young shop assistant directions to Visoki Dečani - a UNESCO-listed Serbian monastery just outside the town. “What monastery?” she replied wide-eyed. “There is no monastery here.” It was only when we drove the short mile to the site that we understood. The entrance was under armed guard by the KFOR (Nato-funded Kosovan Peace Force). Following the 1997-99 war with Serbia, newly-independent Kosovo bitterly resents the continued presence of any Serbian who has chosen to remain on their territory. Inside this fortified enclave, was possibly one of the most beautiful churches I have ever seen. Over 1,000 orthodox 14th century frescos adorning the walls, inlaid with gold and lapis from Afghanistan. One depicted a unique scene, “The only painting of its kind in the world,” our Serbian host beamed. It was Jesus bearing a sword. It wasn’t that our Kosovan supermarket girl didn’t know about this monastery. She wasn’t allowed to tell us she knew. And we were stupid for asking.

Kosovo was a special place. Somehow the complete lack of other tourists and top sights to see made it all the more beguiling. There were towns which appeared to offer little in the way of attractions, but whose charm lay in their sheer differentness. In Peja we were blinded by the ritzy dazzle of wedding dress shops, stopped to watch a man repair my broken sandal, witness a child bare-foot cleaning the gutter, and paused before an open shop door where inside young girls stretched and cut baclava pastry on a cloth the size of a ping pong table. The girls revel in one foreign word in particular which they are adept at pointing out on signs. It’s only now, 9 months in, that they’ve shown any interest in being able to read. Probably not unrelated to the fact we’ve eased up on the whole home-schooling thing big time. It’s too hot now for a start, and I’ve kind of ceded defeat, acknowledging that Marcus is far better at teaching than I am. He’s more patient, and doesn’t suffer from the frustration that it all seems so piecemeal. Like the fact you teach something one day and it’s disappeared entirely from consciousness the next. I have the word “Shitjet” to thank for this breakthrough. It means “for sale”, but they find it relentlessly hilarious. Sometimes they try and weave the word “shit” into conversation. “This honey is shit,” one of them might remark to a chorus of giggles. When I rebuke, the perpetrator retorts, “But I meant this honey was for sale!”

One highlight has been Albania’s Accursed mountains. By far the most impressive peaks we have seen so far on this journey. Just the name whets your appetite. They rise up before you like a vast vertical wall, softened only by a fringe of pine trees climbing the lower slopes. Above shark-like jaws of rock, arranged in snaggletoothed rows, guard the border to Montenegro beyond. Rain prevented any serious trekking, but just soaking up those mountains shrouded by mist was enough. Warned to stay away from one side of the valley because of the very real danger of brown bears, we scampered around on small excursions, foraging for elderflower, wild strawberries, lemon thyme, oregano and mint. The effort just to get here is testimony to the sense of rugged isolation. The only road in requires you first to travel 2 and a 1/2 hours on a ferry ride across the dammed Lake Koman. And the only way to continue is to walk up and out across the pass to Montenegro. Passing mountain villages dotted with haystacks, houses with wooden shingle rooves, and women wearing traditional Albanian dress, we bounced rather than drove the road to Lake Koman. Arriving by nightfall it was a surreal experience, agricultural scenes abruptly giving way to mining machinery and finally a kind of post-apocalyptic industrial dead end, as we emerged by a hydro power plant. At first I thought we must have taken a wrong turn, but we were waved down and sold a ferry ticket by an obliging young man, who told us to continue towards the dam and park overnight on the ferry. Following his scant directions to “Park in the middle, at the back,” we crawled our way up an ever more desolate road and into an endless tunnel. Just as it crossed our mind we may have been scammed out of €70, we emerged, and implausibly spy a tiny ferry moored alongside the dam wall.

The next morning we are awoken early as other passengers begin to embark. The girls refuse to take off their Albanian t-shirts, and here they attract much admiring attention. A group of young Albanians stop to chat and exchange high 5’s with the girls. One is very pally, with a comedy Estuary accent, “Alright, how you doin’? Yeah mate, yeah, right,” he reels in effortless patter. It transpires he’s spent a few years on a building site in Kent, and despite his status as a self-proclaimed economic migrant, has rather surprising views on the Brexit question. “It’s the Bulgarians mate, taking all the work and that.”

The ferry ride is incredible, just how I imagine the fjords of Norway may look if we ever get that far North. The compact nature of the top-deck makes for a friendly, communal atmosphere. While the young Albanians treat us to rousing nationalistic songs, putting paid to our peaceful surroundings, the girls befriend a group of Scottish pensioners. One man, Brian, is particularly indulgent, and becomes drawn into their play. Before long they graduate from roaring loudly at him, to clambering all over his person, inspecting his jewellery, trying on his shoes, and finally taking pictures of his body parts (all decent) in order to reconstruct later into a collage. A few days later Lulu draws a picture, and labels it “Brian” in her sketchbook.

Braving the bears, one day we dare to head further into the folds of the Accursed mountains, to hike from the village of Çeremi near the Montenegro border. The journey up the rough track is bone-crunching and spliced with the danger of a river crossing. Summoning courage, Marcus revs the engine and plunges across, grating the underside of the van. Its at times like these I wish we had gone for a 4WD. Felicity Evans you were right! When we can go no further we stop, and try to continue on foot. But within minutes the rain, which has never strayed far, is back, and we are soaked to the skin. Like so often on this trip, unwittingly our misfortune presents a unique opportunity. We find ourselves taken in by an Albanian family, sheltered from the rain, fed and housed for the night. Our “saviour” so to speak is some sort of scout, on the lookout for reckless souls such as we. Instinctively you sense there will be a catch, but we opt to follow him regardless, curious as to how things will play out. He is wearing the most incongruous outfit, given the location - a black baseball jacket with pinstripe trousers and black leather shoes. It looks even more ridiculous a few moments later when he confidently coaxes us across another river bed, where this time our van becomes firmly lodged. With a shrug he attempts to push us out, and the wheel spin flings mud all over his smart office wear. We’re taken to a farmhouse, and find ourselves in a small, low space where a family leap to their feet to greet us. A stove dominates the room, which, by the look of the beds made into seating, and the sink in the corner, serves many purposes. With no common language to fall back on, it is a bizarre mixture of mime where we play as best we can the theatre of hospitality. Our “scout” introduces the family, and we believe we can discern the relationships: a man, his wife, two daughters and his sister. The girls break the ice best, drawing the little 5 year old girl, Linari, into play by dressing up the family’s cat. The room is roasting and while we strip off, a round of buttermilk drinks are laid before us. It’s a challenge to say the least - rich, creamy, cold milk with an island of butter bobbing below a greasy surface. I watch as Marcus slurps a lump into his mouth, trying to disguise a grimace. Next comes the home-brew - distilled Reiki - followed swiftly by Turkish coffee. For the last month I’ve dismissed this coffee due to the fact it tastes like drinking warm earth, but out of the 3 drinks on offer it is by far the most palatable. “Hmm,” remarks Marcus. “We’ve got all the makings of a deconstructed White Russian here. Shall I go and fetch the cocktail shaker from the van?”

The dairy theme continues. For dinner, the family lay a table top on the floor, scatter cushions around and gesture for us to sit down while they load up food and perch behind to watch us eat. There is pasta with cream, a yoghurt soup, salad and another dish of cheese melted in butter. That night we are shown to our “accommodation” in a back shed, consisting of two damp rooms with no lights. The girls room comes with bunkbeds and a chainsaw in the corner. Ours has a man’s clothes hanging up and musty-smelling bed clothes. The next morning things turn sour - and this time it has nothing to do with the rancid salted yoghurt and bowl of melted cheese we are served for breakfast. The “guide” wants us to pay €110 for our stay, which by Albanian standards buys you 2 nights in a slap-up luxury hotel. It’s all a bit tense, as we only have the equivalent of €40 in Albanian currency, so we sit around for a while trying to ascertain whether they will allow us to leave or if things might turn nasty. In the end it is only the children who say their farewells without a trace of awkwardness. Little Linari has become attached to a pair of sunglasses, which the girls gracefully donate, blissfully unaware of the deals their parents have struck.

We still have the odd day of meltdown, when tiredness, endless questions or long hours of driving frazzle all of our nerves. But generally things are pretty harmonious, and the girls are markedly better at the art of negotiation now. Elsie in particular has blossomed in confidence, talking and chatting to people we have just met in a way she never would have done before we left on this trip. I’m amazed at how well they take it all in their stride. We are told “Twin team Albania” must remove their t-shirts in Serbia - an inflammatory act in the current climate. At the Kosovan border the guards purposely don’t stamp our passports to prevent problems later on. Elsie and Lulu kind of absorb it all, our whispered asides at border controls, and attempts to explain the tensions. They have an imprecise but workable understanding of both religious divides and communism now. Our favourite capital city has been Tirana, in Albania. Small, but relaxed, green and leafy, we took the girls to study the socialist realism paintings in the National Art Gallery, pointing out and discussing what they thought about the fresh-faced men and women depicted as mighty, eager workers. There have been so many border controls - including one where we walked from Croatia into Bosnia just for a coffee across the narrow Una river. The first thing they do, after studying the flag, is to ask, “So are they Muslim or Christian here then?” just to ascertain whether its safe to get out their Albanian t-shirts and football emblazoned with the flag of Kosovo. A few times we’ve just pulled off a motorway by a toll pay point and one of them will sigh, “Crikey, Is this another country again?”

But the onslaught of change and unrivalled hospitality doesn’t seem to faze them. Stopped by the Danube in the Serbian town of Donji Milanovac one day, we watched the girls scramble around a playpark, weaving between an army of gun-toting young boys. One father, with an 8 year-old son, engaged Marcus in conversation. Before long we had an invitation back to his house for a drink. I sometimes wonder what Elsie and Lulu make of these situations - what they sense when we find ourselves in odd places, trying unfamiliar home-made specialities, never knowing where we will be, who we will meet from day to day; following their parents into the unknown. Where the adults are nervous and thick-tongued, they act without hesitation - goofing around with 8 year-old Michaelo, who speaks impressive English. Too impressive in some respects - skidding his bike and yelling “What the fuck!” with obvious relish.

We have now racked up 16 countries in 9 months. In that time over 100 camping spots have been our home for a night or longer. I like to think we leave each one as we find it. Our only markers a tell-tale puddle of run-off water, and a small pile of swept scrapings from the van floor. Shells, nuts, pebbles; downtrodden relics from the recent past. But in truth, it is not all we have left behind. Our belongings are scattered all over Southern Europe - clothes, 4 pairs of shoes, tweezers, a stool, shovel, bodyboard, hats, sunglasses, 3 towels, 2 cheese graters, and an iPhone. All sacrificed along the way, through sheer carelessness or neglect. Each day a small parade of objects dance past us through the door, carried away to be used as props in Elsie and Lulu’s latest show. Before we depart, Marcus and I attempt to do a minesweep of the van’s curtilage, but invariably we fail to retrieve the odd thing, left behind like a discarded offering. Our plan of attack has been to tax their pocket money instead. It seems the only way to inculcate some concept of personal liability. So far Lulu has replaced her own hat and my tweezers from her savings, and Elsie saved up for 2 weeks to buy Marcus a new shovel. Their new found wealth has also proved a useful safety net for us. On at least 3 occasions we’ve had to raid their reserves after finding ourselves caught short at borders or toll booths.

There is a new urgency now, as we can sense our time is running out. The loop of the Balkans took as as far inland as Bulgaria. Our destination was the a tiny village in the countryside near Vratsa, visiting an old University friend of Marcus’s, Cen Rees. Despite having no contact for 10 years, it was effortlessly easy to be in his company, along with his wife Chrissy, daughter Islay and baby Olly. Another of their UK friends, Karen, was staying with her daughter, Tenzin, and we spent a glorious 4 days cooking outside, walking in the meadows and swapping stories. The simple way they lived their life - rich in time, not in possessions - was a pleasure to behold. The girls made mud pies, searched for horned vipers and spent many happy hours studying the contents of the long-drop compost toilet by shining down a torch. Little Islay’s biggest hero is the chubby survival specialist Ray Meers. While Cen treated us to a demonstration of fire-lighting “a la Ray”, Lulu picked up Islay’s considered way of speaking, with a Eastern European twang.

We have now moved on to Croatia. It feels like one big tourist theme park compared to the rest of former Yugoslavia. But at least here we can feel the breeze of the Adriatic coast, as the heat of summer begins to bite.

1 note

·

View note