#maybe instead of arguing about the shorthand words we use we can actually discuss the politics that matter?

Text

its just such a basic view of feminism to me i guess. like we cant talk about how emasculation is an enforcement of toxic masculinity, how it is racialized, how it effects both transmascs and transfems. bc mens rights arent real, of course, feminism is about womens liberation, not destruction of the patriarchy.

we cant talk about how misandry (such as it is) is a dogwhistle for terfs, bc of course they only ever mean transfems when they say "men". we cant talk about the ways white cis women have utilized toxic masculinity and white supremacy to harm black men, specifically. we cant talk about the ways cis women hold privilege over trans men.

its just so... like... you rush to say "misandry isnt real" because you dont want to engage with the more complex dynamics of oppression that arent as clear cut as "cis man oppress cis woman". and like, sure, misandry isnt real. i dont care enough to squabble over what language we use. and i dont care enough about whatever silly jokes you make on your blog. but you have got to realize that by only ever seeing men as inherently oppressive to you by merely existing you are actively aiding radical feminism.

you are lending legitimacy to bioessentialism by refusing to engage w these more complex gendered oppression dynamics. you are lending legitimacy to bioessentialism by treating men as inherently different and inherently oppressive to women.

#its so....... frustrating#maybe instead of arguing about the shorthand words we use we can actually discuss the politics that matter?#if u cant see a man as your friend and an ally and only ever see him as The Social Class 'Male'#then frankly i dont see how we're ever making it out of this lmfao#maybe some bell hooks will fix you#also like yeah ok people of an oppressed class can joke about their 'oppressors' (as if oppression is a thing individuals do consciously an#not a thing that happens by means of a system in place that perpetuates it. and that certain people happen to benefit from)#but like . this is white cisfeminism we are talking about you know?#misogyny as an oppressive system splits the world roughly in half it is#incredibly broad and i think its very damaging to just#generalize men as people. esp bc there are MANY cases where manhood is simply not Enough to the white patriarchy#idk i thought everyone learned about emmett till you fucking know?#when its harmless its harmless but when its not its racist terf shit and half the time people dont even know bc they think being a woman me#ns they are constant victims and can never ever perpetuate the WHITE cishet patriarchy the way men can#which is just false

1 note

·

View note

Text

I do actually feel like there is value in saying what you actually mean. I’m well aware that the concept is mostly championed in more or less that verbal form by Petersonites and online ‘rationialists’ and the like, but what we see on Tumblr every day is...

People use rhetoric shorthand constantly to talk about very, very serious and valued topics like sexual ethics, structures of healthy relationships, all the various axes of oppression that exist in this world, abuse, embodiment, while relying on mostly informal associations between certain words, concepts, and discourses.

As a result, sometimes you see people conflate positions such as “pride was never an all-ages event” with “fucking in public at pride is fine so long as you do it in front of adults, there is no such thing as a ‘time or space’ for such activities” or maybe “you should escape from relationships, even platonic ones, if that means you need to take care of yourself” and “you can just cut everyone off whenever as if they never even mattered, and this is sustainable community policy.” And then we all have a big argument that lasts a week with usually a lot of people staunchly refusing to actually say what they are talking about or corollarily, refusing to understand what other people actually mean by what they’re saying.

(Of course, some of those positions is imaginary, but I would argue that it is exactly due to being vague that people think these positions actually exist at any sort of real threatening scale within our communities.)

There’s a lot of usage of the word ‘freak’ and ‘creep’ and even sometimes ‘degenerate’ (!) while somehow assuming that everyone means exactly who you DO mean, while also knowing exactly who you DON’T mean, even though by using certain rhetoric frames you’re going to reinforce their usage by cishets regardless of whether that’s your intent or not. It’s would seem unwise to insist that people who suffer (even worse than you) under various conservative and repressive frames should be perfectly stoic at all times and take you at your word that you’re not targeting them in some cryptic way or another.

A lot of people seem to think they’re completely fluent in this network of loose semantic and aesthetic associations that exists within our community, but when someone has any sorts of questions or commentary about frankly, the extremely vague or purposefully inflammatory shit that is sometimes said on this website, this is treated as essentially already guilty behavior since OBVIOUSLY that means that they’re simply of the weird position that people are projecting onto them. At the same time, these people often project particular niche sexual interests on people they only know through a few decontextualised Tumblr posts. Very strange behavior!

Maybe just because men like to go on about Logic and being Precise In Their Speech or whatever — it’s not like they themselves perform it anyway — it shouldn’t mean we shouldn’t properly expound on what we mean so that the things we say can’t be co-opted by reactionaries of various kinds.

More importantly, maybe when people are being quite clear on what they’re saying we shouldn’t project whatever kinds of perversions and evils onto them just because it reminds you of some weird things you’ve seen or experienced and you’ve decided you need to immediately go ‘feral’ about it.

(Especially when it comes to transfeminine people — almost all of whom I know to be extremely intellectually thorough and persuasive people — make long-form critiques on certain aspects of sexual ethics or a similar endeavor this should be held up as particularly valuable perspectives that are often overlooked in our larger community instead of that a bunch of clowns go “OMGGGG WHAT DOES THIS MEAN I CAN’T READ 😂😂😂” in the comments.

Also, that when transfeminine people talk about the way in which certain frames of discussion injure their dignity and freedom to live as they please, you shouldn’t immediately assume they’re being perverts just because they’re attacking your favorite shorthands you love to hurl at your Online Enemies lol)

510 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Miys, Ch. 78

Okay, I checked. This is actually chapter 78 :)

Thank you, again, to @zommbiebro for the name of the colony. This will be way more important than people realize.

As runners-up, @baelpenrose and @iguessthisisme, thank you for the names of Else’s new habitats. While the reason isn’t given (you are free to mention them in the comments), they did rank as the runners-up.

I made an appointment with Miys to continue our talk about other species next week and sent messages requesting a small meeting in my office. When I arrived, Alistair already had everyone seated and was handing out drinks. Dropping into a chair, I grabbed the one Tyche passed me and took a deep sip, narrowly avoiding a sputter when I realized my coffee had at least one shot of whiskey in it. “Geez and fuck, Worthington, what are you trying to do to me?”

Taking the cup from me, he inhaled deeply before apologizing. “It was meant to be coffee with Irish crème, not Irish coffee.”

“Whatever, give it back.” Pinching the bridge of my nose to avoid the looks I was inevitably getting, I made a blind grabbing gesture with the other. “By the time this conversation is over, I may need this to be sans coffee.” I inhaled deeply before looking up. “We have a problem on the Ark.”

“That’s nothing new,” Tyche pointed out. Beside her, Antoine gave a regretful look of agreement along with an eloquent shrug.

Groaning, I arched an eyebrow at Arthur Farro, who sat across from Tyche, on my other side. “You see how often this kind of shit happens?” With that, I launched into what happened in the corridor with Miys, specifically the crowd of people plowing into us. When I finished, I held up a hand to stop the outpour of questions from Farro and focused on Antoine. “Can the update to receive proximity alarms be disabled?”

“In theory, yes,” he answered hesitantly. “But I’m uncertain if the entire implant would have to be disabled in order to do so.”

“Our hosts should be able to tell us if the implants can be turned off,” Alistair pointed out.

“Mmmmm… you would think so. But I asked, and apparently they didn’t even think we would be able to understand any of their technology, much less futz around with it on the scale needed to create the proximity alerts in the first place,” I explained.

Tyche nodded firmly. “That means we use our secret weapons.”

“Derek?” The question came from our resident former-warlord, who was still not used to our shorthand.

“And Zach to run herd on him,” I confirmed. “If we can determine whether it’s just the update or the entire implant that’s disabled, Derek can turn the right thing back on and lock user privileges down so they can’t be messed with again.”

Raising one hand for attention, Antoine ventured a point. “Are we - is the Council - okay with the ethics behind forcing people to use the translation implants?”

My head dropped heavily onto the tabletop. I hadn’t even thought about that, but he had a point.

“We can argue ethics later,” Tyche interjected. “First, we have Zach and Derek determine what part of it isn’t working. If it’s the update, there isn’t anything to worry about, since the Council already agreed that it was in the best interest of the ship as a whole to make the receiver software compulsory.”

Thank you, little sister. When I lifted my head after a silent prayer, I saw Farro giving Tyche an evaluating glance before turning to me. “So. Were these the same people you two mentioned at the dinner?”

“I think so.” Opening my datapad, I pulled up the questions he sent me. “So, on that note, since that’s why you’re here…. ‘How large are the groups?’ I would say three to seven people.” I tipped my hand back and forth in a vague gesture.

Tyche nodded. “I tend to watch my data pad as I walk but the groups aren’t too big. Five-ish? Sometimes more sometimes less? Not suspiciously big though, that I can say for sure.” She opened her own copy and tackled the next question. “Any frequent meetings...The clusters seem to be everywhere, but it's the whispering and watching that make me uncomfortable. I'm face-blind, though, so I couldn't tell you if these are the same groups.

“To be honest, meetings happen all the time on the Ark. Granted, there are generally fewer after the misunderstanding with Else - “ Alistair scoffed so hard I was worried for his sinuses, but I ignored him and plowed on. “but I would definitely say nothing overt enough to stand out.”

Before I could reference the next question, Farro pre-empted me. “Have you noticed people from these smaller groups interacting with each other? Or groups combining, mixing?”

I had to roll my eyes that one. “Dude. It’s literally my job to get people to interact, so the only answer you’re getting to that one is ‘all the damned time’.”

He turned to Tyche, eyes hopeful. She just gave him a smirk. “What do you get when you mix an elephant and a rhino?” When he looked perplexed at her non sequitur, she leaned forward. “Ellephino. Faceblind, remember?”

Scowling, he shook his head. “You handle staffing… how the hell do you do your job?”

"I do it damned well, if I do say so myself," she waved off his complaint. "Which I do. Voices, body language, key accessories... Been doing it my whole life."

“Fair,” he shrugged, seemingly satisfied. “Sophia, have you noticed if it’s always the same people who are clustered up?”

I couldn’t stop the groan that question elicited. “Arthur. There are over nine thousand people on this ship. It would be nearly impossible to be sure.”

He grumbled something about ‘no self preservation’ and ‘what happened to proper paranoia’ before asking the last question. “Please tell me someone at least noticed if they got noticeably quieter when any outsiders came near them?”

My sister and I exchanged glances before I responded. “Eyeah. Kind of why they stand out.”

How did Farro avoid getting dizzy when he rolled his eyes that hard?

Antoine cleared his throat, catching everyone’s attention. Leaning forward in his seat, he ran a tired hand through his hair. “Tyche mentioned these groups to me a few days ago. I’ve been keeping an eye out and while they aren’t the same groups, there are the same people with new groups, sometimes two at a time in the larger gatherings. Much like a very hushed spreading of word about….something. I have no idea what of course. I’m usually on my way to either medical or a client.”

“Wait,” I held my hand up for a moment. “Same people with new groups? What do you mean? Like, intermingling groups of these people?”

“Think of a social butterfly, but more secretive. There are some I recognize from other groups, but surrounded by different faces. Mingling but spookier.”

Tyche nearly choked on her drink. “You’ve been around me too much. ‘Mingling but spookier.’”

“At least someone noticed something useful,” Farro grumbled.

“Hey!” I complained. “I get that you’ve got a theory, but you don’t have to be rude.” I scowled at him.

Okay, maybe I pouted.

After a moment of deadlock, I took a drink of my coffee and arched a brow at him. “You know. If you told us what exactly your theory was, this would go a lot better. I get that you’re used to working on your own, but you’re asking questions that are leaning into things we aren’t going to notice. It’s like… asking a vet if they’ve noticed any fleas lately. Even if they don’t just ignore them outright, it’s nothing remarkable.”

“A cult,” he admitted, sitting back and taking a drink of his tea, only to glare at it like it betrayed him. Getting up, he went to dispose of it and asked the console for a hot, fresh cup. “People suddenly acting weird, closing off others unless they make the first move? Cult, all day long.”

“That’s pretty overt for a cult though. Most of the time, it’s hard to tell when someone is part of one. They were surprisingly common back Before,” Tyche immediately interjected, having suddenly gone eerily serious. “I’ve known former members. They creep in.”

“Not that overt,” he pointed out. “Scientology.”

“A fake religious movement, that if not for a certain celebrity wouldn’t have gotten so much attention.”

“Oh, completely fake. Not even the founder believed the bullshit he was slinging,” Farro agreed. “But, it was also a very overt, definitive cult.” He started counting on his fingers. “There’s also Jonestown and the Manson family, as far as cults that withdrew from society, although the somewhat limited space of the Ark makes it easier to just get quiet instead of trying to isolate.…” he trailed off before seeming to snap out of his thoughts.

Tyche groaned at the point. “And the non-religious ones, such as multi-level marketing and pyramid schemes.”

“Of which there were several in the latter half of the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries,” I pointed out. “Very famous and popular ones, actually. So. Being overt doesn’t mean this couldn’t be a cult.” My stomach twisted at the idea of something like that forming in the midst of our chance to be everything good we had the potential for. It felt like someone doused the Mona Lisa with acetone.

“To be fair, it could also be a more harmless, mysticism based situation like the legionary sect of Mithras in ancient Rome, so we don’t necessarily need to assume the worst - just plan for it, in case.”

“If we concede that this could be a cult,” Alistair volunteered, “I feel it would be wise to discuss the matter with Councillor Hodenson.” Deafening silence followed his statement, broken only when he squinted at our group in confusion. “Grey Hodenson? The Councillor for Research and Sciences? Who was raised in a cult?” Another emphatic squint before he sighed and threw his hands up. “Unbelievable. For a group of supposed geniuses, you all show a breathtaking capacity to overthink things.”

“I believe we should also include Councilor Kalloe,” Antoine advised. “As the Councillor for Health and Safety, it is imperative that she is kept abreast of the situation, even if it is unfounded.”

“It would also give us a stronger likelihood of a majority in the Council if it came to a vote,” Tyche confessed. “We’d already have three out of six, would just have to convince one more.”

“Let’s hope it doesn’t come to that,” I groaned. “But yeah, subject tabelled for now, until we can reconvene.” I forced myself to sit up straighter. “Now, enough bad news. Tyche, Antoine, someone, give me some good news.”

Antoine spoke first. “The portion of Else that is not in coldsleep is adapting well to its new habitats. It is quite pleased with the compromise, and reports excitement at the opportunity to speak to more humans.”

My eyebrow arched before I could stop myself. “Do I even want to know why that is in your purview?”

“Therapy is therapy,” he shrugged eloquently. “Adjusting to new environments is stressful for all living creatures, even those not known to be sentient.”

Alistair added, “Additionally, a nebula has been located that is determined to be sufficiently large and ferrous enough for Else to colonize. They have determined to name the nebula Esperia, to symbolize their origins with humanity and their hope for the future. When we locate a similarly suitable planet or planetoid, they have decided upon Redemption, or the equivalent in whatever language they have evolved by that point.”

“Wait,” Farro stopped my assistant. “You mean to tell me that a bacteria decided on a name for two colonies before we could decide on one?”

“Only by a breath,” I smirked, opening an alert on my datapad. “Apparently the name for our new home was just approved by the Council. Good news indeed.”

Several seconds of silence followed as everyone stared at me intently, with Tyche and Alistair pointedly ignoring the similar updates they had just received. Finally, my sister broke. “Are you going to share, oh mighty Councillor, or does everyone have to wait for me to leave and spill the details?”

Laughing, I gestured my concession. “The name that was agreed upon, by a five to one majority within the Council, is Von. ‘In Norse religion, Ragnarok is the end of the world, followed by a period of rebirth and renewed hope. Our world has already ended, this we agree upon to point that we have all simply named the chain of events Before, The End, and After. The new colony will be our renewed hope, our opportunity to be reborn as a better people. In that spirit, I put forth the name Von, which simply means hope or expectation in Icelandic. Nothing could be more fitting for our new home, after our own Ragnarok’.”

Heads nodded in agreement. “That’s a good name,” Alistair admitted. “Not my suggestion, but still good.”

<< Prev Masterlist Next >>

#the miys#humans are weird#sci fi#original writing#apocalypse#aliens#humans are space orcs#original fiction

71 notes

·

View notes

Photo

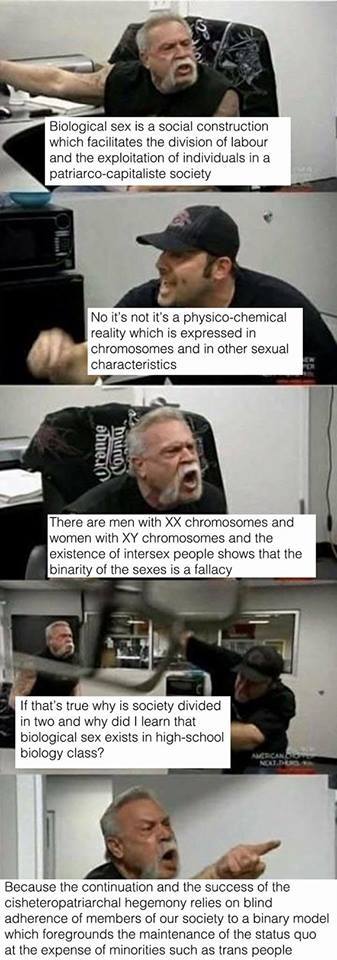

I’ve seen this meme being talked about by my sister and some of her friends, and there is a lot going on here. They were saying that something felt off about it but they weren’t sure what. What’s off is that it’s very poorly argued, and relies on rhetorical tricks. Let’s walk through it panel by panel, and then discuss the meme as a whole.

Panel #1: The assertion is that Biological sex is a social construct, which they attempt to support by saying that the motive was to create a society where one class loses out for the benefit of another.

The first problem with this argument is that biological sex does not describe our social roles. That’s what gender is. So the argument remains unsupported. The second issue is the over use of jargon. The majority of audiences are going to have a difficult time understanding what the author is trying to say here.

Panel #2: This is a logical counter-argument to panel one. There is scientific evidence to back the claim. It uses complex terms, so it could stand to be simplified for broader audiences, but there isn’t anything majorly wrong here.

Panel #3: This one appears pretty simple at it’s face, but there is actually a lot to untangle here. Let’s break it down into a simple argument pattern and work from there.

Statement 1: There are XX Men and XY Women

Statement 2: Intersex people are are neither male nor female

Conclusion: Human sexes are nonbinary.

With Statement 1, this one lives or dies based on how you define man/woman. If Man means “Adult Human Male” than there are no XX men. If Man means “Someone who identified as a man” than man describes a social role. Social roles aren’t a manifestation of sex. So either way, Statement 1 doesn’t support the conclusion.

Statement 2 is factually wrong. A biological sex describes the type of gamete (one of the cells needed to make offspring) an organism is trying to produce. Humans only have two gamete types, and a given person can only produce one of them. Intersex people’s bodies only try to produce one or the other, they don’t produce some third gamete or both. And all this is before the fact that calling them sexless is actually intersexist and discriminatory, but I’ll let someone who’s more well versed in the subject elaborate on that.

Since both statements are unrelated at best, and false at worst, the conclusion is unsupported again.

Panel #4: Notice the sudden shift in tone? In the previous panel, this guy was depicted as overly wordy and verbose just like the bearded guy. Now he’s speaking in plain language. His first line about “why the divide” would have been addressed in the first panel, had that panel been talking about gender. The second line makes no sense for him to ask since he already stated that biological sex was reality based on science, which would be why he learned it in school. So why would he ask that?

Because he’s been set up as a strawman. He’s no longer representing an actual opposing argument. He’s instead saying something bordering on irrelevant to set up panal 5 for an easy takedown, while discrediting the side he’s meant to represent.

Panel #5: The meaning here is absolutely drowning under jargon, to the point where it needs translation. Furthermore, this is a run-on sentence, which can be difficult to parse even when they have simple phrasing. So to understand, we’re going to need to break things down again. First, let’s suss out what the words and phrases mean:

Cishetropatriarchal Hegemony: Cishetropatriarchal implies “not transgender, straight, lead by males” and hegemony means a leadership, usually of nations, and often with expansionist goals.

Binary Model: Here this means male/female biological sexes.

Foregrounds: Usually used in visual arts, the antonym of “background.” It’s supposed to convey putting one group over another.

Status Quo: Our society as a whole, at this moment. It has a charged implication in this instance, since it’s becoming political shorthand for “everything that’s wrong.”

We’ve got a bit closer to understanding what’s being said, but we’ve still got a hell of a run-on sentence to deal with here. Unfortunately, the phrasing makes it nearly impossible to tell how the author intended the sentence to flow. Interestingly, since this opens it up to reader interpretation, that gives the author room to claim that any given critique is misrepresenting the content. To try and leave the sentence as intact as possible, we’ll split it in two:

“Because the continuation and the success of the cishetropatriarchal hegemony relies on blind adherence of members of our society to”

Simplified: To continue successfully, our non-trans, straight male leadership needs people to follow blindly

“a binary model which foregrounds the maintenance of the status quo at the expense of minorities such as trans people”

Simplified: A Male/Female model of human biology is the basis that the status quo is founded on. The status quo is maintained in a way that causes harm to minorities, such as trans people.

That took so much breakdown and reassembly, by now it gets hard to remember what this was even a response to! But now we can stick everything back together and analyze what it actually being said. To summarize, we had Hat Guy ask “Then why is society divided in two, and why is biological sex taught in schools?” and the Beard Guy essentially says “Because to continue successfully, our non-trans, straight male leadership needs people to follow blindly (which supports the status quo.) A Male/Female model of human biology is the basis that the status quo is founded on. The status quo is maintained in a way that causes harm to minorities, such as trans people.“

With the haze of jargon cleared away, the argument doesn’t work, because it is still founded on the basis that biological sex is a social construct. The simplest test to see if something is a social construct is to ask what would happen to it if humanity lost self awareness and society. Does the presumed construct survive?

Without any labels, we’d have one type of human who could produce sperm, and one that could produce eggs and carry offspring. You can only make offspring when you match a sperm producer with an egg producer. That is what sex is, in the most simple and basic terms. Biological sex exists in absence of human understanding. So the argument would fail on that fault alone.

Interaction Between Panels #4 and #5: This is where we get into some pretty clear rhetoric, which merits close examination on it’s own. Rhetoric can be used to bolster a well made argument, but it can also shore up a bad argument, since the purpose of rhetoric is to just “feel” true.

We have Hat Guy, who is representing the opposing argument. His shift in tone and sudden use of simpler language is used to imply his arguments have failed, and he’s only resisting out of stubbornness and prejudice. We’re meant to scoff at his ugly ignorance.

Then we have Beard Guy, who is set in place to make that sick take down that the audience can revel in. The panel has an accusatory air to it. The phrasing, where it isn’t making things murky, is highly emotionally charged. Phrasing like “blind adherence” paints Hat Guy, and by extension, the opposing side, as feverishly devoted to a lie.

The undercurrent of the argument in panel five implies that by taking his position, Hat Guy is supporting a system that’s using and abusing an underclass for its own gains. Without saying as much, it evokes a similar gut reaction to being told you’re supporting slavery. It’s framed as a brutal and just take down.

So rather than dismantling the opposition with counter points backed by accurate evidence, Beard Guy has instead attacked the argument with pure rhetoric. He’s guilting the opposition, defaming their character by implying they’re stupid and/or immoral. The evidence provided, rather than being dismantled, has been dismissed and forgotten.

To get all of that information across, using relatively few words, and in a couple panels is the power of rhetoric, context, and framing situations. It’s a lot to take in, and very emotionally charged. This is why we need to look past rhetoric and into arguments, no matter which side they come from.

The Meme Overall: Alright, so we have a meme here that’s absolutely loaded with poor arguments, logical fallacies, falsifiable facts, and searing rhetoric. So what? Memes aren’t essays, they’re jokes, you aren’t supposed to think to deep about them right? Glance over it, laugh, maybe glance again as you share it and see it again as it passes through your group of friends.

But this isn’t really a joke, now is it? These claims are currently being asserted as facts in long-winded, even harder to digest essays, and trickling out into more mainstream activism. It’s more akin a snippet, a quip, or a piece of an essay that’s easier to swallow. It’s the same ideas, but repackaged in a format that’s easy to understand. We know how this meme goes, who’s right and who’s wrong, and why it should be funny. We know that we don’t need to think hard about what it says.

We have an image here, one that has a clear point of view that it wants the viewer to agree with. One that misrepresents facts, and hides that with buzzwords and jargon. One that paints it’s opponents as blind, irrational supporters of evil. And we have all of this wrapped into a pithy and familiar package for that asks us to take it at face value, don’t think to hard about it, and share it widely. It’s propaganda in meme form.

844 notes

·

View notes

Text

Will Bridgerton Become the Next Game of Thrones?

https://ift.tt/3qPhiRk

Traditionally, when critics discuss “the next Game of Thrones” or when studios, networks, and streamers search for “the next Game of Thrones,” the candidates put forth have much in common, genre-wise, with the late, sometimes great HBO series. They are the Lord of the Rings TV show or His Dark Materials or The Witcher—aka epic fantasy series that, by and large, have the look and feel of a Game of Thrones, ignoring the fact that, contextually, the fantasy elements of Game of Thrones were only one factor in its enormous success.

This isn’t an unfamiliar Hollywood tale. After a massive commercial success, the entertainment industry tends to throw its money behind (for want of a better word) knock-offs—stories that may be good or moderately successful, but are only alike their culture-changing predecessors in the kinds of superficial ways that don’t actually matter that much. Take, for example, the big-screen adaptation of Eragon, which was greenlit following the success of the big-screen Lord of the Rings trilogy. Eragon may have sweeping shots of a small figure amidst the vast and fantastical New Zealand countryside, but the depth, scale, and texture of its enjoyable source material, not to mention the budget and care that went into its adaptation, were not comparable to the Lord of the Rings, and the reviews and box office reflected that.

Genre is a shorthand moviemakers use to communicate to audiences what a film is and why they might like it, so it’s easy to understand why producers would overweigh the importance of genre when trying to recreate the success of a Lord of the Rings or a Harry Potter or a Twilight. But I’d like to shift the conversation, and expand our imagination of where the pop culture landscape could be heading. When theorizing about “the next Game of Thrones,” if what we mean by that is “a mega-successful and long-running show that becomes so central to pop culture that even people who don’t watch it can reference it,” I would argue we don’t necessarily be looking in the epic fantasy genre. Instead, may I put Bridgerton forward for consideration?

Since its Christmas release worldwide, Bridgerton has not only consistently been in the Netflix Top Ten in multiple territories around the world, but also consistently in the news, most recently for its record-breaking success. Netflix announced today (via Deadline) that the race-bending period romance adapted from the Julia Quinn novels is, by some measure, its “biggest series ever.” The 10-episode first season of Bridgerton was watched (either partially or fully) by a record 82 million households, which is 19 million households more than the streamer’s four-week projection made at the drama’s 10-day mark. This means that, unlike many of Netflix’s bright-and-fast-burning Top Ten-ers, Bridgerton‘s popularity is sticking. Bridgerton has already been greenlit for a second season, but it’s not hard to imagine the series running for the eight seasons showrunner Chris Van Dusen said he is hoping for.

Read more

TV

From Bridgerton to Hamilton: A History of Color-Conscious Casting in Period Drama

By Amanda-Rae Prescott

TV

Who is the Villain Teased in The Lord of the Rings TV Series Synopsis?

By Joseph Baxter

But popularity alone does not make The Next Game of Thrones, though it is certainly one major factor. Plenty of TV series have that magic combination of critical and commercial success in their first seasons before fizzling out in the second or third. What makes a Game of Thrones or, dare I say, a Bridgerton, different? Well, for one, like Game of Thrones before it, Bridgerton is a TV show based on a many-book series, which provides a vast blueprint to pull from. Structurally, both source material series have many, changing POV characters. In A Song of Ice and Fire, the POVs characters change from chapter to chapter and, sometimes, from book to book. In The Bridgerton Series, the POV character changes from book to book. This makes for a particularly fertile narrative ground for adaptation, as the source material doesn’t solely privilege one or even a few characters or POV, leaving TV showrunners to balance the ensemble out in the process of adaptation.

Both stories are built around themes of family and power within a complex and often cutthroat world, and they both have a group of siblings at their heart, tying the many storylines together. I’m not hear to make one-for-one comparisons because, honestly, it is the opposite of my point, but I will say: Daphne, who values a more traditionally feminine life, has a lot in common with Sansa Stark and Eloise, who begrudges the pressure to get married and become a mother, is bascially Bridgerton’s Arya Stark.

Game of Thrones and Bridgerton‘s narrative interests diverge in some ways, but they are both structured around the affairs of ruling society, even if those dynamics and scenarios plays out in different narrative languages—i.e. violence/war vs. romance/marriage. In Game of Thrones, the weapon of choice is, well, weapons and the stakes are one’s life and the lives of one’s loved ones; in Bridgerton, the weapon of choice is gossip, and the stake are one’s lives and the lives of one’s loved ones, though measured against a different rubric. In Bridgerton and romance as a genre in general, domestic security and happiness, including and most especially for women, is treated as the valid and worthwhile goal that it is. It is depicted as a victory worth winning in the same way that the accumulation of male-coded political power and military might is treated in other genres.

And let’s talk about the power of the romance genre. Romance is a genre made by and for women and, because our culture tends to devalue the feminine, romance storytelling has a stigma that has historically kept many men and some women from engaging with it. Because of this, fans of romance are a traditionally an underserved audience when it comes to adaptation, despite it being the most lucrative book genre market. According to Glamour, the billion-dollar romance book industry made up 23% of the fiction market in 2016, but the TV and film industry seems surprised every time a Twilight, Outlander, or Crazy Rich Asians comes along, as if they have forgotten that women make up half of the planet’s population.

It’s only in recent years, most notably with the success of bigger-budget romance adaptation Outlander, that TV studios and distributors have started to invest larger budgets in unabashedly romantic fare, presumably because more women and more men who listen to women when they speak have become Hollywood decision-makers. (Though, by and large, the statistics are still dismal and depressing.) For whatever reason, the kind of storytelling that was once only seen in the sphere of the primetime soap (a valid venue in its own right, but one with modest budgets and limited crossover marketing) is now becoming more common in larger, more mainstream arenas. Bridgerton is the perfect example. With its sizable budget and broad marketing campaign, Netflix wasn’t just looking to capture the audience of a Shonda Rhimes broadcast venture like Grey’s Anatomy, but to rebrand romance as a mainstream genre, and the women who love it (many of them Black woman and women of color) as an audience worth investing in.

Read more

Books

How Bridgerton Season 2 Can Improve On Season 1

By Amanda-Rae Prescott

TV

His Dark Materials Now Has One Very Obvious Thing in Common With Game of Thrones

By Kayti Burt

If we’re going to have another Game of Thrones, and I hope we do because they have value in an increasingly fractured culture, then it’s probably going to look a lot different than that great “tits and dragons” fantasy saga. It might have some things in common—such as a large, pretty ensemble cast of characters that allow for multiple entry points; a strong existing source material that gives a blueprint for a complex world and where its families of characters is heading; and the production values to facilitate an escape from our increasingly distressing world into a story that feels the right balance of fantastical yet real. But it’s going to be something new and exciting, the way Game of Thrones was new and exciting for many people. Maybe it won’t be Bridgerton, but it probably won’t be Game of Thrones 2.0. We’ve done that already.

cnx.cmd.push(function() { cnx({ playerId: "106e33c0-3911-473c-b599-b1426db57530", }).render("0270c398a82f44f49c23c16122516796"); });

The post Will Bridgerton Become the Next Game of Thrones? appeared first on Den of Geek.

from Den of Geek https://ift.tt/3iUls7u

0 notes

Text

It was meant to be half-meme, half-pointing something out, but judging by the notifications I really regret making that comparison post between the Johto Journeys OS OP and that shot from the new trailer for the 20th anniversary movie. :/ With that said, though, a bit more real talk before I head to bed---

I don’t think there’s very much point in arguing over semantics, and in this case I mean the semantics between “it’s an AU / retelling” and “it’s a retcon.” First of all, “retcon” is shorthand for “retro continuity,” which means a new version of events which is typically meant to take the place of an earlier version of events within a work, or sometimes fill in details that weren’t there before. A retelling is a retcon, because you’re retelling how something happened while changing details to fit the new version of the story. So if you’re arguing, “it’s a retelling, not a retcon,” you’re contradicting yourself. That’s exactly what a retcon is.

Second, the finite difference between “AU” and “retcon” doesn’t matter, because it doesn’t exist in the minds of the target audience, which is grade-school age children. These children are being told, “This is the story of how Ash and Pikachu met.” And in many ways, it is! There are many details across the various trailers which compass the first four episodes. There is even a shot that is clearly meant to be episode eleven, “Charmander --- The Stray Pokémon.” That TPCi is taking care to make sure that those elements from the OS are faithfully adapted to this new movie (with characterization perhaps altered to account for the Ash they have in the anime now, versus the Ash they had in the anime back then) makes it clear that they’re trying to reintroduce this story to children who were born actual decades after the original series aired, who might not know how it began or unfolded. Yes, they had that 20th anniversary marathon of the first and last episodes of each saga, but that’s not the same thing you and know it, particularly since the anime’s ratings have been in a slump for decades now. Fact is, this movie is being advertised---and rather heavily, at that---as the story of how Ash and Pikachu met. That is what’s going to stick in the mind of, say, an eight-year-old. This is what they’re going to remember, and so as far as the anime goes, this might as well be canon now.

And you can argue, “Well, it’s a movie---the movies are never canon, at least not anymore,” but that’s arguable. The movies are as canon as they’ve always been. Ever since the first movie it’s been difficult to slot the movies in at any particular point within the show’s actual timeline, and the events of the movies are typically never discussed within the show itself. For example, Spencer and Molly Hale---despite being family friends of the Ketchum’s in the third movie, and despite Spencer being one of Oak’s former students---are never once mentioned within the series proper. Although Ash rode a Lugia in the second movie, I don’t think he breathed a word of it in the mini-arc in the Johto series when he, Brock, Misty, and Ritchie encountered the baby Lugia, and so on and so forth. The movies often feel as if they exist in their own continuity, and people have always argued whether or not they’re canon, but I’ve always interpreted the mainstream agreement to be, “They’re canon, they happened, but when they happened in a given saga is debatable.” You can usually figure out a loose spot---for instance, the second movie had to have taken place after the episode “Charizard Chills” due to Charizard listening to Ash---but that’s about as good as you’re going to get.

Either way, this movie doesn’t seem to be any more or less canon than the others in this sense. Will this ever be referenced in the main series? Probably not. But it doesn’t change the fact that it is making glaring changes to Ash and Pikachu’s origin story by removing two of the three main cast members from the first season, replacing them with two brand new characters in the process, while keeping several other important plot details (e.g. the spearow attack, how he met Jessie and James, Metapod evolving into Butterfree, capturing Charmander, et cetera). From the looks of things, the only things they bothered changing in this re-telling is the removal of Misty, Brock, and Gary (who was a side character rather than a main character, given his status as Ash’s rival), and the additions of Makoto, Souji, and Cross to replace them. And that brings to mind a very, very important question: Why?

No, really---why are they doing this?

When this movie was first announced, you had a whole slew of people bemoaning the fact that it was more Gen I shilling, crying that they weren’t interested therefore. Okay, that’s a fair enough opinion to have. However, if that was the case and that was the only reason why this movie was being made, then why wouldn’t they use Misty, Brock, or Gary? Surely, if they wanted to snag the attention of older Millennial fans like myself, they would use the characters we all remember and adore, right? Surely they’d take the opportunity for the cameos, wouldn’t they? If this movie was truly being made to shill Kanto and appeal to the Gen I fans, then wouldn’t it make the most sense to have the Gen I characters there, rather than have then conspicuously absent, replaced, and draw attention to that fact with specific visual callbacks?

And you could argue, “Well, but maybe they want to make this accessible to new fans!” Well, all right---but why are Makoto, Souji, and Cross more accessible to new fans than Misty, Brock, and Gary? The children of today probably only have a vague idea, if that, of who Misty, Brock, and Gary are. They’ve never met Makoto, Souji, or Cross before because they’re new characters. So wouldn’t the same effect be achieved either way? Wouldn’t new kids still be introduced to these characters either way? Why replace Misty, Brock, and Gary, and have that be the only major change (Ho-Oh and Gen VII pokémon shenanigans aside) you’re making?

I guess it just doesn’t make very much sense, except for one possible explanation that I don’t want to share publicly because I know it’ll cause Discourse™. But to say I’m disappointed is an understatement, especially since I thought we were finally having the Ho-Oh subplot from the OS resolved . . . only to find out that we’re not, because the entire movie is one massive retcon. And yes, sure, “we knew that from the hat!” but that doesn’t mean that I wasn’t holding out hope that, even if some things would be changed, they wouldn’t have the only major changes be the removal of characters who were rather integral to Ash’s journey, only to have them replaced by some Sinnoh promoting randos instead.

But oh well. I survived The Darkside of Dimensions. I can survive this.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

ÜbeR-rated

For whatever reason, Word War 2 and Nazism have been on my mind a lot lately, so I finally got around to reading Über, all 27 issues of it, plus the specials and the beginning of Über Invasion. And I wrote a 5K analysis of it in the context of the fictionalization of Nazis. This is a thing I did to myself. And if you don’t want to feel left out, now you can read it too.

Heavy spoilers for the whole Über run, TW for pretty much everything you’d expect from a WW2 comic (except screenshots, because… well). Enjoy (?)

…

What am I looking at here ?

It’s 11 pm here and I’ve been staring blankly at my computer screen for thirty minutes, trying to find the proper way to kick off this essay, when all I had to do was to take a look at the additional rewards of the Kickstarter for the new Über arc, in order to introduce the point I want to start this piece on : I AM VERY, VERY WARY OF WW2-BASED FICTION. It’s not to say I’m opposed to it on principle, as I know some people are ; no matter how hard the topic, there’s always use for fiction. Fiction is a vector. It can be used right and it can be used wrong, but while on some levels it cannot hope to ever hold the same value as historical content, there are similarly elements only a piece of fiction can grasp. And if this kind of ethical discussion is always going to be around, it’s because fictionalization of real-life events is always going to be around. It’s an inevitable processing device of the human mind, and as much as possible I try to examine artistic material without resting my entire appreciation on their rapport to their source material, if only because part of their value comes from their ability to stray away from it.

But if there’s one event around which the tensions between history and fiction have made themselves an integrant and even a central part of any discussion of their artistic merits, it would be World War Two, and more specifically the Third Reich aspect of it. Maybe that’s unfair. But the historicity that has to be worked with on other topics here becomes a prerequisite concern : if the transposition from real events to fiction is handled poorly, it stands at risk of disqualifying the entire work. And even in works from thoughtful, ethically-minded creators (as it is the case with Über) you’re never safe from a “what the hell were they thinking” type of blunder. I hope they still sell those shirts next time I visit an Avatar booth so I finally get something to go with my “I <3 Auschwitz” tote bag.

However, once we get past the fact that the “offensiveness” of the work is always going to be part of the discussion, there is a lot to be said on the link between historical events and their fictionalization on a pure narrative level. Even when this fictionalization is done wrong from an ethical point of view, it can teach us a lot about our own need for fiction and the inner workings of real events-based artworks.

I felt this introduction was necessary, as this piece is going to feature both discussions of the ethical stakes raised by the choices Über made when fictionalizing WW2, and discussions of the same choices from a storytelling and aesthetic perspective. Nevertheless, even when these two aspects – ethical and artistic – are discussed separately, it should be understood that they are coexisting lenses of appreciation of Über as a whole, and that a negative or positive appreciation of a narrative choice from one perspective should in no way be taken as a validation or denigration from the other. To put it simply, the fact that I will praise some of Über’s creative decisions doesn’t mean I consider them free of ethical issues ; reciprocally, my criticism of Über’s handling of some ethical issues doesn’t mean I consider it worthless as a piece of art.

If you are of the opinion that ethical deficiency should prevent any artistic analysis of this work to take place, I will not argue ; similarly, if you want to avail yourself of a right to enjoy fiction without concerning yourself with ethical debates – well, you’re wrong, but that’s not an argument I will start here. Personally, I think these two aspects need to be analysed concurrently here, as Über is kind of a perfect case study in WW2 fictionalization in that it’s a thought-provoking work in large part because it is riddled with questionable choices, instead of being thought-provoking in spite of them.

In conclusion to this introduction folks, Über is a land of contrasts.

The Three Big Bad Wolves

At its most basic level, the premise of Über is nothing that hasn’t been done before : at some point in WW2, we enter an alternate timeline in which Nazis somehow manage to take the advantage thanks to a technical breakthrough. It’s a handy premise as it has long served as an oblique way to discuss the American use of the atom bomb in Japan, and the subsequent nuclear race, without being hit with the “would you rather have had the Nazis win the war ?” inevitable defence. Put the dangerous toy in the hands of the most recognizable villainous figure of the 20th century, and suddenly, the conversion loses its controversial aspect. However, I’d also argue it loses its pertinence. It doesn’t have to, but more often than not, the identification of debatable means to an undebatable villain tends to wash out any reflexion on the mean itself to instead reinforce the evil of the character. The Nazi atom bomb is evil because it’s Nazi, not because it’s a weapon of mass destruction. There’s no equivalent to the nuclear escalation started by the US bomb in the Nazi atom bomb timeline : any technological progress made to counter Nazis is ultimately being coloured as good, because it’s fighting Nazis we’re talking about.

This is where Über does something interesting : instead of trying for a weak “no blameless sides” approach that could only pale in comparison with the culturally engrained goal of stopping Nazis, it turns the original premise to eleven and watches it unfold. The Nazi atom bomb is not just the American one with the eagle painted black, it’s one that dons an unmistakably Nazi idea : the rise of a superior race of men. So when the USSR and the UK and then the US have to retaliate, they have to do so by implementing a technology that is tainted with the very ideology they are fighting against. In that sense, it’s very telling that we see this technology collide with the Allies’ own racist ideology : America is willing to put itself at a disadvantage by under-employing some of its potential “enhanced men” because they are black. In the war of ideas presented in Über, Germany has already won : it’s now fighting on its own field.

That’s the enhanced men premise in terms of sides ; what about the enhanced men on their own ? Where do they stand in the context of fictionalizing WW2 ? There’s of course an inevitable comparison to be made between Captain America and Über, but one I will leave to someone who actually knows their stuff about Captain America. Instead, I want to look at this premise from a larger perspective : is there a use for a superior version of Nazis ? A sci-fi device is handy to compensate for an overpowered adversary ; in Über’s case in particular, any modern WW2-based fiction has to work with the limitations of hindsight : we live in a world that was built on a Nazi defeat, therefore it is hard to conceive of a winning Germany without somehow rebalancing the odds. This is where fiction might benefit from a re-actualization that is inherently impossible for historical material : we could make Nazis win, so we can beat them again.

However, this is where the unicity of WW2 as an historical event comes to undercut the use of fiction. WW2 and the Holocaust aren’t just real events : they were a cultural breaking point. To grossly paraphrase Theodor Adorno, one cannot think in the paradigm that led to Auschwitz anymore. With the end of WW2, a page of the human book of thoughts was turned. Our intellect, our culture, came across something that couldn’t be assimilated : both had to be profoundly rerouted to make sense of the world. Nazism is an intellectual dead-end : it represent the moment an entire intellectual and cultural paradigm imploded into total loss of meaning. What it means is that, even today, Nazism is Nazism precisely because we can’t conceive of it, and yet it did come to exist. Understanding the historicity of Nazism takes more than faith in the facts ; it takes suspension of disbelief IRL. The key factor in understanding the cultural impact of WW2 is its reality. Nazis aren’t scary because they were evil, they are scary because they were real. So if your premise is something along the lines of “Nazis, but scarier”, all you can accomplish is further remove Nazism from what gives it its cultural impact and straight into fiction territory. By pushing it into deliberate incredibility instead of forcing the audience to confront its actual incredibility, you anchor your story into a sanitized environment in which Nazism has been replaced by its cultural shorthand. Your Nazi is evil, but they’re not real, and therefore not scary.

This is why to me, using fictional enhancement to compensate for the historicity of Nazism is a device that is doomed from the start. This is a case where Reality wins ; even the slightest confrontation to real-life Nazi brutality has more narrative impact than all the sci-fi body horror in the world. What it meant for me reading Über is that I was aware of the impact the übermensch were supposed to have on the reader but I never felt this impact for myself. I’d argue the scariest moment in the whole Über run occurs in the Special, specifically Markus’ backstory. Here we see a child born into national-socialist ideology commit a hate crime. The implacable use of infantile impulses to indoctrinate hatred ; now this is a taste of the unbelievable Reality of Nazism. In comparison, Klaudia destroying all of Paris elicits no emotion because it belongs wholly in the cogs of fiction.

Now this would be alright if Über’s only ambition was to tell a story set in the context of WW2, but it’s a comic with the ambition to make a statement about WW2, meaning it wants me to be invested both in its actual story and in the fact that it’s a WW2 story. But it doesn’t work as a standalone story because its stakes are so rooted in its historical basis, and it cannot hope to one-up this basis as a work of fiction. As a result, Über sits uncomfortably between its premise and its stakes, lowering the latter by furthering the former.

Killing cities in a night, repeatedly

The fictionalized and historical aspects of Über also come to collide in its graphic decisions. Violence – both its level and its regularity – is a recurrent issue encountered by WW2-based works, including non-fiction ones : what to show ? How much to show ? This is a matter of responsibility but also impact : setting a standard of violence is also what will help you to highlight and judge these actions relatively. What kind of violence do the “good guys” allow themselves ? What is the line that indicates a wrongdoing ?

WW2 here comes with its specific set of problems, as it is an era in which brutality and barbarism wasn’t only pushed further than ever before, it was also generalized and systematized ; meaning that violence can virtually be present at every instant and not feel like an exaggeration. Moreover, there is such a variety of ways this violence can be painted, from clinical and cold to outrageous and unbearable, that each representation of violence cannot help but feel like a statement.

Every WW2-based work has provided us with its own answer to this problem. In Merle’s Death is my trade, the violence of Auschwitz is perceived through the eyes of a detached, efficiency-minded SS top officer : here, violence is a numbing succession of technical examination, the result of a cost and benefits analysis devoid of any empathy. In Inglorious Basterds, Tarantino went in the opposite direction : this is one of his least violent films from a frequency perspective, but when violence occurs, it is never anodyne. Sometimes it is glorious, other times gruesome, but the movie makes sure you are there to appreciate every single bit of it.

So safe to say there are many ways the litany of horrors of WW2 can be approached. But the solution Über came up with is in my sense a particularly creative, meaningful one, and one I can’t recall ever seeing before. Violence is Über is ever-present, ever-extreme, and yet somehow always centred. Generally, representing violence in WW2-based work takes the form of an arbitration between frequency and impact. You either use violence to world-building purposes in order to create an ever-brutal environment, or you save it to put emphasis on a couple of significant moments. But in this debate of violence as a beat versus violence as a drop, Über never really takes position. Every other panel features someone being ripped apart, some mash of flesh on the ground, every confrontation brings its lot of snuff visuals. It should be numbing or acclimating, but we are forced to keep paying attention by the constant spot the story shines on it. Violence in Über is both the stage and the play ; even when it has relatively little effect on you – as it is my case – you are always half-forced to integrate it and half-forced to focus on it.

But even more interestingly, if everything is violence, then it means there is no background or forefront violence. A plot-wise insignificant rape of a nameless character in the first issue is depicted with the exact same crudeness as HMH Churchill’s leg ripping off during the most decisive battle of the first arc. No violent act is either meaningless or meaningful. No violent act is ever narratively highlighted, therefore no violent act is ever justified. I’ve often read that Über “doesn’t pick sides”, but it definitely does ; what it doesn’t pick is a demarcating line. Violence is the great equalizer of Über : brutality is brutality, whether it’s kicking a puppy or winning a war. This is a courageous position because it goes beyond the “all sides are bad” easy rhetoric of most Manichean WW2 narratives. The violence in Über is not a rhetorical tool, it is not up for discussion, it resists both analysis and relativizing. It is a whole that cannot be picked apart and deconstructed. This is a very punk rock use of violence in that it says almost nothing but makes it emptiness meaningful.

[I can’t help, however, but point to the only narrative decision so far I consider unequivocally wrong : to wait until the story takes place in the US in Invasion to dedicate some consequent space and speaking time to casualties and civilians. I know where this decision comes from – render the stakes of a Nazi invasion more personal to an historically untouched America – but the fact that this is the first time this aspect of war is evoked on its own feels not only like a gross erasure of actual history, it perpetuates the long Hollywoodian tradition of only being able to care about things when they happen to good US citizen. Somehow I feel like if millions of people can march around the world in preventive solidarity with the US, any member of the presumed Anglo-Saxon readership should be able to grasp at the horror of devastated Europe and Asia without being able to spell the last name of the victims. Anyway, Über Invasion #2 is a perfect example of how a good standalone chapter can lose all of its compelling power when taken in the context of its own series. Back to the essay.]

The Jewish Question

yup and I’m sure this header will never bring in my notifications the delightful people who frantically search it on every website

Because violence is an equalizer in Über, it means everything that’s represented in the comics stands at the same level of horror as everything else. What this entails is that, if there is something the authors do consider reaching a superior level of horror, this superiority cannot be expressed within the pages ; there is no way to double down on ultraviolence. Therefore, the only solution to do this particular act justice is to leave it out. There are no degrees of violence, only representation or lack thereof. And this is a determining factor Über uses extensively.

Despite being described in virtually review as “uncompromising”, I find Über to be on the contrary built on compromise ; only the compromising happens before anything makes it onto the page. Because of its particular subject matter, it gives ethical significance to anything “making the cut”, which reveals a level of thoughtfulness of the creators that I wish I could see more often around difficult material.

And maybe with no surprise, there is one thing Über is decidedly not showing. I call Über a WW2 comic, a Nazism comic, but it is not, by any means, a Holocaust comic. You could count on one hand the number of times the camps are mentioned ; we witness but two acts of antisemitism, and that’s if we include the special ; of the two featured queer characters, one is a Nazi ; there is no Rromani character ; and if not for Leah Cohen, the comic would be entirely devoid of named Jewish characters. Really, this is such a glaring hole in the comic’s narrative fabric that it cannot be something other than intentional. The comic twists into at times frankly comical contortions to avoid the subject : the Nazis are experimenting on humans, but they’re mostly non-Jewish Slavs. Bloody doctor Mengele shows up and he doesn’t do a goddamn thing.

So I think the intentionality is pretty clear here. Now I’ve said in my Tara piece that I will always respect a creator’s decision to stay away from a topic if they don’t see themselves having the legitimacy or the shoulders to handle it properly. It’s especially true when this decision was made out of respect for that topic, which I believe was the case here. I do see why one would want to avoid discussing the Holocaust in their comic about human nuclear bomb Nazis wiping off most of Europe.

However justified – and possibly right – this choice was, it begs a different question regardless : can you make a comic about WW2, and one exploring literal Nazi doctrine at that, that mostly ignores the Holocaust ? Well obviously you can, but can you make this work meaningful while cutting out the most central and recognizable aspect of WW2 ?

Let’s say it straight up : I don’t have an answer to that. I don’t think an abstract answer can even be given here. But we can look at the answer Über gives us.

On a pure narrative level, Über does evacuate most of the problem by situating its story after the liberation of the camps. I’d argue that given what a pressing matter the imminent discovery of the camps by the Allies was to losing Germany (google “death march” next time you feel like your life is going too well), it’s hard to conceive why Sankt didn't just take one of the battleships for a stroll to the camps and have them literally blink every evidence out of existence, but let’s accept there are in-universe reasons why the topic can be cautiously worked around.

On a conceptual level, things are more complicated. Über is a comic about WW2, but one that explicitly focuses on Nazis and Nazi ideology. It’s natural for a work about Pearl Harbour not to peep a word of the Holocaust. But when the foundation of the comic rests on Nazi soldiers and the people directly fighting them, the absence of the Holocaust aspect feels like there’s something missing. As a thought experiment, I tried to imagine if the comic would have worked if it had taken place in WWI instead. The protagonists are similar, so are, roughly, the battlefields. There is virtually no reason why WWI Germany wouldn’t work as an antagonist in a sci-fi comic. In fact I’m pretty sure there’s at least one comic out there with this scenario. And yet it feels like Über wouldn’t work at all in WWI. As a second thought experiment, I wondered if the premise would have worked if the Allies had come up with the enhanced human first and realized I’d invented Captain America.

In both instances, the transposition doesn’t work, because of one reason : Nazis. As I said earlier, there is something irreplaceable in the combination of Nazi characters and Nazi ideology-based sci-fi. Über doesn’t work as simply “a war comic in which one side gets enhancing technology” because its core relies way too much on our shared understanding and approach to Nazis. And this is where the absence of a Holocaust narrative in the plot can deprive it of meaning. Nazism is Nazism and not Any Other Nationalist ideology because of the Holocaust. The world we live in today is built on the identity between Nazism and the Holocaust. You cannot think of one without thinking of the other. So when Über rests its premise on Nazism while consciously avoiding discussing the Holocaust, it’s effectively using Nazis out of their context and into a made-up one. It borrows the cultural significance of Nazism while cutting out its signifier.

This leads to a bizarre situation in which only two of the Nazis featured in Hitler are ever seen partaking in Nazi ideology, and the people who are actually seen torturing an – albeit willing – Jewish character are British. A situation in which the entire core of the racist Nazi ideology feels like a bygone idea destined to die with an insane Hitler to make room for tacticians and economists.

To reiterate, I don’t know if leaving the Holocaust out was the wrong decision or not. Maybe the risk of feeling exploitative was too great and the creative team was wise to leave it out as much as possible. But as a result, it can’t help but lean a bit more on erasure. The fact is that when your mean of respecting something is to leave it out, then you won’t have the opportunity to compensate for whatever opposite content does make it in the comic. There is nothing offensive about the Holocaust in Über, but there’s nothing reverent about it either.

Prisoners of fate

In fact, there’s not much reverence for anything inside Über. There is respect as I’ve discussed earlier, on a structural level, determined by what makes it into the comic. But what gets to be on the page cannot expect any kind of special, tasteful treatment. I think Über readers only learned exactly what they were in for with the concurrent deaths of Hitler and Churchill. If Hitler gets regularly offed by more or less talented creators, Winston Churchill is one of the Gandalfs of WW2, an immediately reassuring presence who eases out your reading by bringing one certainty to it : no matter how bad things get, he’s not going to die. This is the most commonly adopted bias in WW2-based materials : preserving historical figures in order not to throw the audience too much off track. In Über, historical figures enjoy no such immunity. This is an extreme but equally crafty solution to the coexistence of reality-based and purely fictional characters. This is a problem with which a fair share of WW2-based works struggle. Take something like Costa-Gravas’ Amen : the superposition of real-life figure Kurt Gerstein and fictional character Riccardo Fontana doesn’t work at all, as they both serve basically the same narrative purpose and diminish each other’s impact on the story. But in Über, a character’s real-life basis always comes second to the internal logic of the story. That’s not to say there isn’t room for them in the grand scheme of things, but as more and more enhanced characters take the stage, these characters can’t help but feel more and more irrelevant. That is maybe the great paradox at the heart of Über, that it still features a division between the enhanced soldiers instead of one between them and regular humans – a transition Wicdiv underwent recently. I suspect the simplifier or this paradox lies on what Über has to say on Authority, but I’m saving that subject for a separate essay.

But this “no character is ever safe” stance contributes to another sentiment that runs all the way through Über : implacability. This is a very fatalistic comic, probably even more than Wicdiv. This is particularly palpable in the fight scenes. Despite what the covers would have you think, battles in Über are quite short : four, five pages at best before something breaks it down. But most importantly, they are predictable. There is no last minute turnaround in Über : the second the protagonists collide, you know who’s going to fall short. The only unknown factor is just how scarring this defeat will be. Not only that, there is no narrative logic as to who’s going to emerge the winner : Allies are not due a victory because they last suffered a loss, no side can expect proportional returns to its sacrifices, no battleship is guaranteed to win out of virtue of being a charismatic character. There is only one law in Über, and that’s the Rule of war. The winning side wins because they had the superior technology, the superior information, the superior strategy. The issue of a battle is settled long before the two enhanced fighters even meet, as two groups of high-ranking officers stand above some maps. This is why the story of Über so often seems to be happening in its own background : most of the time, what we see is a consequence of the plot more than the plot itself.

The story is not completely devoid of typically Gillen-esque clever bits, like the “cloning” of Hitler and pretty much everything about Maria. But those are outstanders waiting to be integrated in the grand logic of the story, and until then, often feel out of place – Maria in particular.

Then there is the second lens we have to see the story through, one that gives the story the full measure of its fatalistic weight : the narration. I said I wasn’t particularly touched by the art on its own ; however, the contrast between the extreme graphics and the cold, factual narration is one of the comic’s best assets. One of the issues’ back pages feature a script excerpt describing a gory mutated monster in very graphic details ; but this sort of writing never makes it into Über. The narration is abundant, but always curiously removed from the visual action, at times even clunky and annoying to read. I wasn’t sure how to make sense of it until I got to a particular description of a piece of art created by the power of the enhanced men. What was interesting is the mention that it was the “first” one, something that would be impossible to know unless you were observing the scene from a distant point in the future. The narration is dry for a reason : this is archivist talk. Whatever perspective we’re observing the story from, this is one that is way ahead of us, possessing some additional information, short on more trivial matters. Über only tricks you into thinking this is a re-actualisation of WW2 : in its own timeline, the war we’re looking at is long over. The fictional heroes, the historical figures, the technological progress, the countries, they are all trapped in their little sandbox, playing a game that only seems undecided, when in reality everything that will happen will do so to arrive at that unknown moment in the future, the vantage point from which we are watching the ants burn each other.

How can you read Über while holding this intense feeling of vanity ? You can’t ; you have to get into the story, do what the narration cannot do, get closer to these characters, and try to understand them. But you can never fully connect with them either : you are from a different world, both outside and inside the story, a world built on the ashes of the one fuming under your eyes. A world that had to reinvent itself to make sense of the contagious barbarity born of revenge, ideology and desperation. What does the world Über is talking to us from look like ? Does is look like ours ? Is it better ? Worse ? Only one thing is certain : it, too, has suffered a scar. One that may never actually have healed. And this is why, despite the inherent limitations of its premise, despite maybe being too well-minded for its own good, despite the tragic irony of trying to one-up the Nazi threat right at the time it’s being proven the world doesn’t need any kind of incentive to fall for the exact same act a second time, I still think there’s a place for something like Über in WW2-based material. At its core, like several other works over the last year, and maybe premonitorily, Über is about what killed the world.

17 notes

·

View notes

Link

It was mid-afternoon on our second day living in Hawaii, and I woke up groggy from a much-needed power nap. I stumbled into the kitchen where my girlfriend was sitting on the floor with the guy from the cable company. He had come to set up our internet – something we direly needed, because our house is situated in a lush valley with no mobile phone signal. But, I realised, they weren’t even talking about the internet. Instead, I found, he was inviting her to come boar hunting with him.

You may also be interested in:

• The code that travellers need to learn

• The Swedish word poached by the world

• The Greek word that can’t be translated

As the days passed, the friendly happenings increased. We stopped by a neighbourhood farm and were offered avocados from the caretaker’s tree. We arrived at the end of a hiking trail, or so we thought, when a passing father and daughter offered to show us the secret additional part of the path that led up a rock face, over boulders and through a stream to a hidden waterfall. On another occasion, we were headed for a swim in the ocean, when someone on shore warned us that the current was too strong to swim safely, then offered us a beer and invited us to go canoeing.

There may be many words to explain these kinds of encounters, but at least one of them is ‘Aloha’. And as it turns out, ‘Aloha’ is actually the law here.

View image of In Hawaii, ‘Aloha’ is more than a greeting – it’s the law (Credit: Credit: Danita Delimont/Getty Images)

Hawaii now hosts almost nine million visitors a year, and ‘Aloha’ is a word that most of those tourists will hear during their time on the islands. The word is used in place of hello and goodbye, but it means much more than that. It’s also a shorthand for the spirit of the islands – the people and the land – and what makes this place so unique.

“Alo means ‘face to face’ and Ha means ‘breath of life’,” according to Davianna Pōmaikaʻi McGregor, a Hawaii historian and founding member of the Department of Ethnic Studies at the University of Hawaii, Manoa. But McGregor also noted that there are several less literal, but equally valid, interpretations of the word.

Aloha is a concept that grew out of the necessity for Hawaiians to live in peace and work together

One especially memorialised interpretation was shared by a respected Maui elder named Pilahi Paki at the 1970 conference, Hawaii 2000, where people had gathered to discuss the past, present and future of Hawaii. It was a time of heightened disagreement in the islands, over Vietnam and other political issues, and Paki stood up to give an emotional speech about the Aloha Spirit – in other words, the unique spiritual and cultural code of a Hawaii that is uniting rather than divisive. In it, she described what Aloha meant about the way people should treat one another.

In her speech, she broke each letter of ‘Aloha’ down to one phrase. And that speech became the basis for Hawaii’s Aloha Spirit law, which essentially mandates consideration and kindness:

“Akahai, meaning kindness to be expressed with tenderness;

Lōkahi, meaning unity, to be expressed with harmony;

ʻOluʻolu, meaning agreeable, to be expressed with pleasantness;

Haʻahaʻa, meaning humility, to be expressed with modesty;

Ahonui, meaning patience, to be expressed with perseverance.”

Although the Aloha Spirit law didn’t become official until 1986, its origins are deeply rooted in native Hawaiian culture. Aloha is a concept that grew out of the necessity for Hawaiians to live in peace and work together, in harmony with the land and their spiritual beliefs, McGregor told me.

View image of The Aloha Spirit law is deeply rooted in native Hawaiian culture (Credit: Credit: Babak Tafreshi/Getty Images)

It makes sense. Hawaii is the most isolated population centre in the world: the California coast is around 2,400 miles away; Japan is more than 4,000 miles. The islands are small – most (like Maui, where I live) can be driven around in a single day. Then, as now, there are no bridges connecting the islands, and even inter-island travel is a challenge. With nowhere to go, the only option, it would seem, is to get along.

“Being isolated, historically, our ancestors needed to treat each other and the land, which has limited resources, with respect,” McGregor said. “For Hawaiians, the main source of labour was human. So there was a need for collective work among extended families and a high value placed on having loving and respectful relationships.”

Like any place, she added, Hawaii had its problems with people abusing power. But, she said, there’s evidence that if a chief was not acting ‘‘with Aloha”, peace-loving Hawaiians would find ways to get rid of them.

View image of The islands’ isolated location led Hawaiians to place a high value on respectful relationships with one another (Credit: Credit: Brandon Tabiolo/Design Pics/Getty Images)

It’s not so different from how the Aloha Spirit law is applied today.

According to the Hawaii State Attorney’s Office, the law is mostly symbolic, but that doesn’t mean it doesn’t work – especially when political leaders or business people get out of line.