#modern screen magazine

Text

Modern Screen Magazine, September 1942.

#gene tierney#modern screen magazine#1940s#old hollywood#old magazines#old movies#old movie stars#classic hollywood#old hollywood glamour#old hollywood actress#vintage style#vintage fashion#vintage#40s#classic movie stars#40s movies#1940s film#1940s movies#40s film#classic film stars#40s style#1940s style

656 notes

·

View notes

Text

Modern Screen Magazine Vol. 41, No. 2. July, 1950. Original Caption: Backstage, chorine Burt Lancaster right, tries to cheer up Floradora girl Robert Mitchum—who doesn't seem very elated about the whole affair.

#more from the frairs’ frolic!#modern screen magazine#friars' frolic#1950#robert mitchum#burt lancaster

96 notes

·

View notes

Text

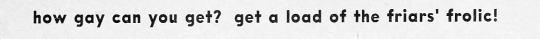

Vintage Magazine - Modern Screen Magazine (Dec1936)

#Magazines#Modern Screen Magazine#Film#Merle Oberon#Norma Shearer#Barbara Stanwyck#Carol Lombard#Vintage#Art#Ads#Advertising#1936#1930s#30s

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

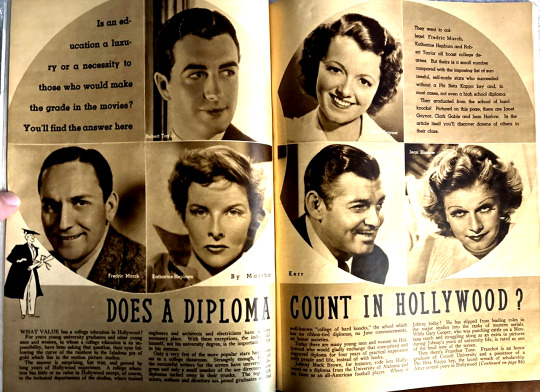

How sweet you both ❤️

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Modern Screen, March 1937: Man of the Auer by Dorothy Spensley

Transcript of article:

Mischa steals a scene a minute, but there’s not a star who resents it

To Mischa Auer, sad-eyed, thirty-one, a Russian refugee, tragedy is the cause of his riotous screen humor. Victim of a bloody era, orphaned at fourteen, his film antics are the results of his deliberate efforts to forget the tragedy his youthful eyes beheld.

If you roared with laughter at his ape-like buffooneries in that crazy sequence in “My Man Godfrey,” rolled in the aisles at his satiric portrayal of the stoic Indian in “The Gay Desperado,” remember that the excellent humor of this fellow stems from a deliberate effort to stamp out the horror-memories of his youth.

“America, too, is responsible for the kind of comedy I am now doing,” says this foreign-born humorist. “The humor of America is built mostly on ridicule. You ridicule customs, institutions, people, politics, national worries. It’s a great idea, because, in the case of troubles and worries, their tragic proportions are reduced by the satiric attacks.

“When I came to New York sixteen years ago my attitude was typically Russian, morose. The things I had seen in my fifteen years had naturally served to make me serious, old in mind, unable to see any humor in life. Starvation, death, the overturning of an ancient regime- I had watched and experienced all these things.

“In America, I soon saw, no one starved. There was security. That, to me, is the most vital thing in life. There was no danger of death by political intrigue. Anyone could get enough to wear. From a tense, under-nourished boy- I was only five feet tall when I was fifteen; as the result of food and care, after that age, I shot up to my present six feet two inches- I became laxed, anxious to absorb the spirit of this new country.

“I soon realized that Americans don’t nurse old grudges- generally speaking. This was radically different from the Russian notion, where an old injury rankles within a man’s mind for years. Also, American humor seemed to be founded on ridicule of the adversities of life. It was easy for me to launch into that vein, anxious as I was to forget the life that I had led in my childhood. Around home I clowned. In the theatre, though, which I joined when I was nineteen, I was always cast in tragic or villainous roles. After eight years in Hollywood, the films have at last discovered that I am a comic. But when I act funny for the camera, I am not acting. I am doing just what I do around the house or at parties. I’m getting paid for being myself, not for acting.”

If Auer’s professional problem seems complex, the break that brought him cinema attention is not. If Gregory LaCava had not remembered, as he was making “My Man Godfrey,” that one of the members of his cast, namely, Mischa Auer, had a panicking “gorilla act,” and that he had seen it eight years before at a Hollywood party, Mischa would probably still be not more than a glorified bit player.

There is one reservation to this. About the time of “Godfrey,” Rouben Mamoulian cast Auer as a strong, silent Indian, with marked satiric overtones, in “The Gay Desperado.” All Auer had to do was to walk around with a heavy expression, a colorful blanket, dank locks, a sugar-loaf hat perched atop his head (in 133-degree-Arizona-desert temperature) and, without saying a word, express disapproval at the waning savagery of Mexican banditry. Auer said for a month he did nothing but lift heavy lids and drop them, witheringly, until he was ready, in his own words, to “commit suicide from boredom.”

Mischa didn’t do away with himself, however. Instead, when the two films, “My Man Godfrey” and “The Gay Desperado,” were released, one on the heels of the other, a new discovery loomed on the Hollywood horizon.

Chestnut-haired, pale-faced and black-eyed Auer accepts the news that he is Hollywood’s newest funny man with the same fatalism that he accepted his mother’s death, of typhus in Constantinople; his flight from Russia with her when word reached them that she was on a Chekov (Bolshevik Secret Police) execution list; that his father had died on a battlefield of the Russo-Japanese War; that, at twelve, he was to be taken with a trainload of children to Siberia as a Communistic child-rearing experiment.

Utterly modern, entirely disillusioned, but not at all lacking in a warm, friendly interest in the human race, Auer furls his mournful eyelids and hopes that his success doesn’t mean that he will have to attend Hollywood premieres. While he likes a lot of chi-chi about his dinner table- gold plates, fine porcelains, finer linens, he lives simply, dresses simply, and is entirely happy with his Canadian-born wife, the former Norma Tillman, and their three-year-old son, Tony.

“I didn’t marry for love, you know,” he answers a question. “I married for companionship. My wife is the grandest and funniest person in the world. She clowns around as much as I do, and we’re always laughing.” continues Auer.

Mischa Auer has other claims to fame besides his recent film success. He is a grandson of the late Leopold Auer, Hungarian-born, Russian-naturalized violin instructor to Jascha Heifetz, Mischa Elman, Efram Zimbalist. More than that, with his parents’ tragic deaths, his grandfather, who died in 1930, legally adopted him and Mischa assumed his name. Young Auer’s real name is Ounskowski. His mother was Leopold Auer’s daughter. Mischa, which is short for “Michael,” has it figured out that he has Hungarian, Russian, Swedish and Jewish blood.

“Little Michael” was born in St. Petersburg. To this day Mischa (pronounced “Mee-sha”) refuses to mention the city of his birth by any other name, although through successive political changes it has become Petrograd and Leningrad. In 1917, when he was twelve, the Red Revolution burst with all its horror upon Russia.

Mischa’s family was “petty nobility.” They were entitled to a crest and a crown with five prongs on it. Barons had seven prongs on their crowns; counts, nine. Tastefully, the Ounskowskis made no use of their small title, preferring to remain upper-class bourgeoisie. Nevertheless, when the revolution broke, Mischa and his mother were immediately listed as aristocrats.

To make all men equal was the Communits’ ideal, so, with a number of other children of aristocratic families, Mischa, at twelve, was hauled off to Siberia to be raised according to Communistic principles. Fortunately for the children, it was spring when this idea took form. Spring in Siberia is not as bad as winter in that far north land. It was bad enough, however.

But the children, as youngsters often do, became their own saviors. They snatched food as they could, robbed, stole, begged, and soon proved a nuisance to the very people who had high hopes for their transformation from little aristocrats to little Communists. They were soon bundled back onto a train and returned to their homes.

Mischa’s joy at being aain with his mother was short-lived. Soon they were fleeing for their lives. In the days of the Czarist regime, Madame Ounskowski had been active socially. One of her activities had been that of patroness for a musicale. The list of patrons had been headed by one of the Grand Dukes. Scouring about for signs of treason on the parts of their newly-created comrades, the Chekov discovered an old letterhead listing the sponsors of the musicale. The Grand Duke’s name was enough to direct suspicion to the patrons and patronesses. Soon the police were searching for all persons whose names appeared on the letterhead.

Weeks later the Ounskowskis found themselves in Turkey. They made their way to Constantinople, then occupied by the British Expeditionary Forces. By the time he was fourteen, Mischa was serving the British Army. He was not actually fighting, but there was plenty of leg work the eager youngster could do in Constantinople.

His mother, too, soon founded a hospital on a nearby island in the Black Sea. It was for refugees, and Mischa joined her there. But the story of Mischa’s life, which should ordinarily end on a fairly happy note, speeds on. In Mischa’s fourteenth year typhus raged in Southern Europe. People died like flies. One of the victims was Mischa’s mother.

Grief might have overwhelmed many a youngster of his age, but Mischa had long since stopped shedding tears. Crying was a waste of time in the midst of the colossal desolation that his generation had been born into. Mischa prepared to do the last thing he could for his mother… bury her. It was Sunday, and the Sabbath in Turkey is religiously celebrated. Not a shop was open. No one worked. He could get no dray to carry a casket to where his mother’s body lay. He walked to the casket-maker’s shop and carried his mother’s casket home on his back. It was a muscle-tearing, heart-breaking task, but he did it.

Left alone in the midst of pestilence, Mischa thought how he might escape. A few jewels remained in his mother’s belongings, which he sold. Then he found his way to Florence, Italy, where a girlhood friend of his mother’s lived, married to a local attorney. They welcomed the haggard lad; fed him, clothed him, then cabled his grandfather, Leopold Auer, in New York. The music master sent for his orphaned grandson.

Here, again, should come a happy ending to a terrible childhood, but, no. Grandpa Auer’s secretary met the wrong boat, and Mischa was shunted into Ellis Island. Mischa’s first impressions of America were not pretty. Characteristically, he holds nothing against anyone for that experience. Incredible episodes in his life have left him numb to trivial discomforts. Then, too, don’t forget the natural fatalism of the Russians, “What is to happen, will happen, and nothing you can do will stop it…”

In New York, Mischa’s life at last became that of the normal youngster. He enrolled in the Ethical Culture School, a private institution, concerned with proggressive ideas in education. At nineteen Mischa went on the stage. That seemed to be his life work. Now he wants to become a director. He is not without experience in this work. In the East he conducted his own summer stock company, giving one-act plays. On Broadway, he appeared in “The Wild Duck,” “The Riddle Woman,” “The Kibitzer.”

Touring with Bertha Kallich players brought him to Los Angeles in 1928. Once there, he entered films; displayed villainy in “Lives of a Bengal Lancer,” “Clive of India,” and others. Now, under long-term contract, Universal has him doing a comedy Hamlet in a night club set-up, with a negro Greek chorus, interpolating and adding the syncopated note, in “Top of the Town.” He recites the Soliloquy, and the skull is electrically lighted, the eye sockets blinking on and off. Mischa, with irony, relishes the idea immensely. Also, he relishes the part of the “ham” film actor that he is doing, at the same moment, for Hal Roach’s “Pick a Star.”

The Auers are naturalized American citizens. His favorite author is the typically American Gene Fowler. Auer’s biggest surprise, besides that of his sudden picture popularity, came when an Eastern publisher turned down a lengthy version he had written about his hectic life. The publisher undoubtedly thought he was exaggerating. That is exactly what Mischa would not bother to do. Why should he, when, in his case, truth is more devastating than fiction?

#mischa auer#modern screen magazine#old hollywood#1930s Hollywood#30s movies#1930s film#classic comedy

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Modern Screen sugar-rationed holiday recipes

Modern Screen sugar-rationed holiday recipes

The holidays are a time for baking and partaking in sugary sweet treats. However during the years of rationing, preparing these goodies was made difficult.

Though rationing ended with the close of World War II in 1945, sugar continued to be rationed through June 1947. Modern Screen provides some holiday candy recipes in the Jan. 1947 issue with substitutes that will still allow for goodies.…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

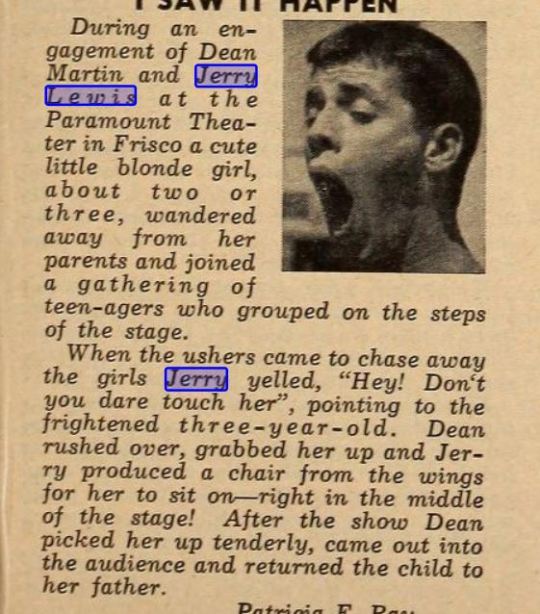

Malibu Tournament

Modern Screen, December 1931

#buster keaton#1930s#1910s#1920s#1920s hollywood#silent film#silent comedy#silent cinema#silent era#silent movies#pre code#pre code hollywood#pre code film#pre code era#pre code movies#damfino#damfinos#vintage hollywood#black and white#buster edit#old hollywood#slapstick#norma talmadge#gilbert roland#dolores del rio#robert montgomery#bebe daniels#modern screen#1931#magazine

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Modern Screen, August 1940

#jean arthur#magazine: modern screen#year: 1940#decade: 1940s#type: studio and publicity photos#ms vol. 21 no. 3

314 notes

·

View notes

Text

from Modern Screen, February 1932

original caption:

Joan Blondell finished "Union Depot" with Dough Fairbanks, Jr. She is now busily at work on "The Roar of the Crowd." She plays opposite James Cagney in that one. Joan will wed Cameraman George Barnes, according to reliable reports, when Mr. Barnes' divorce from his present wife becomes final. Joan's wedding is to be at the Little Church Around the Corner.

Photographer: Irving Lippman

#1930s#1932#1930s fashion#big pants#joan blondell#modern screen#pre code hollywood#fan magazine#film magazine#classic hollywood#my edit#vintage style

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Modern Screen Magazine, April 1949.

#ava gardner#1940s#modern screen magazine#old hollywood#old magazines#old movies#old movie stars#classic hollywood#old hollywood glamour#old hollywood actress#vintage style#vintage fashion#old hollywood actors#1940s movies#40s movies#40s#classic movie stars#classic cinema

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Burt Lancaster practicing his horizontal bar routine in preparation for a four week stint with the Cole Bros. Circus, 1949.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

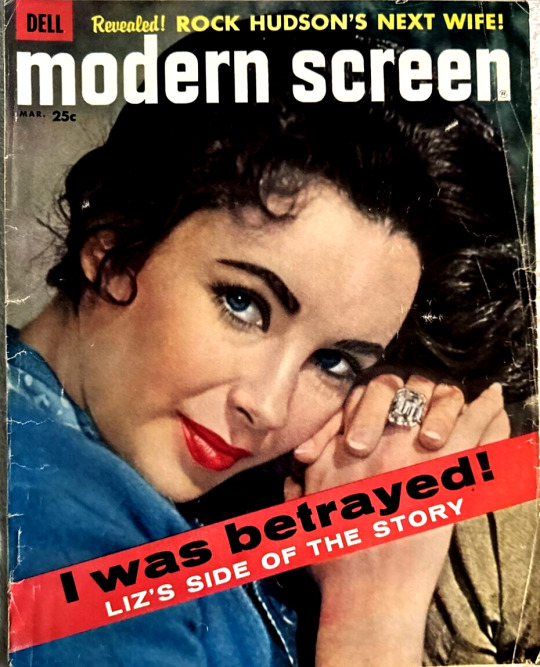

Vintage Magazine - Modern Screen (Mar1959)

#Modern Screen Magazine#Modern Screen#Film#Elizabeth Taylor#Rock Hudson#Vintage#Photography#Advertising#Doubleday Book Club#Book Club#Ads#1959#1950s#50s

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Were they having lunch alone with no attendants, just the two of them? If so, I find it romantic...

And in the photo they play eating something from the same plate.

#dean martin#jerry lewis#martin and lewis#having lunch#together both#modern screen magazine#1953#these two!#Always as a couple

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

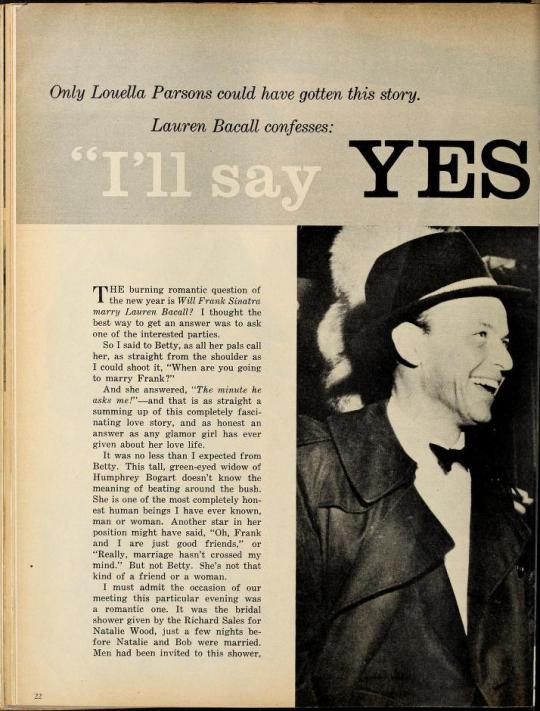

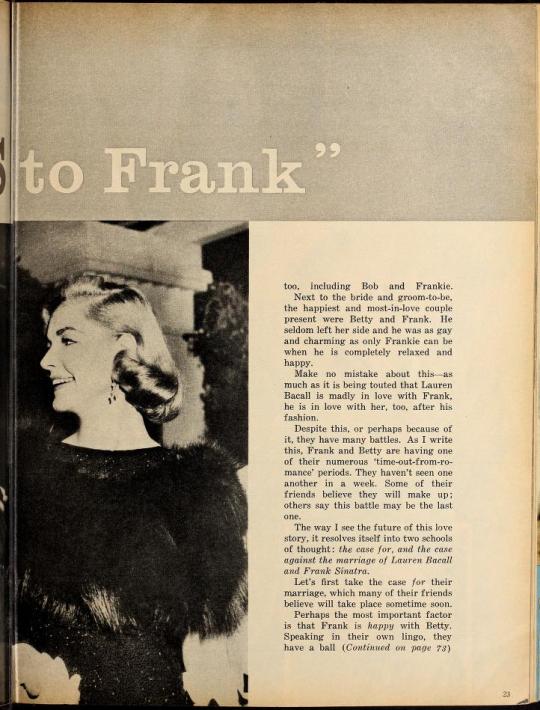

MODERN SCREEN - APRIL 1958

"I'll Say Yes to Frank!"

Source: Media History Digital Library

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

2 notes

·

View notes