#montgomery c meigs

Photo

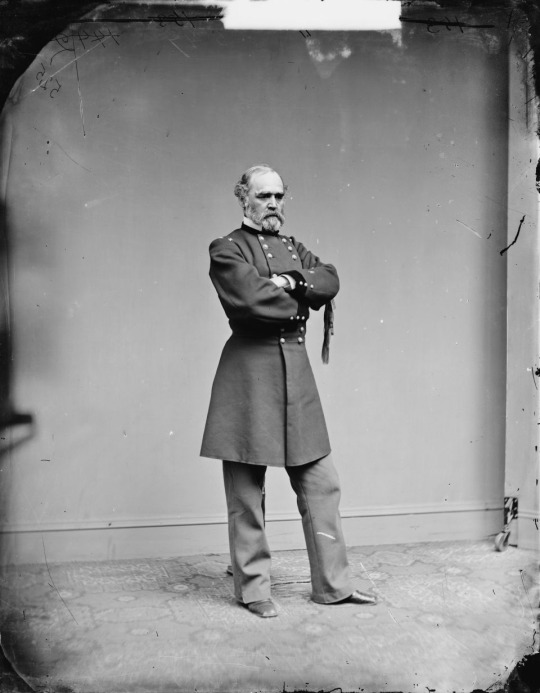

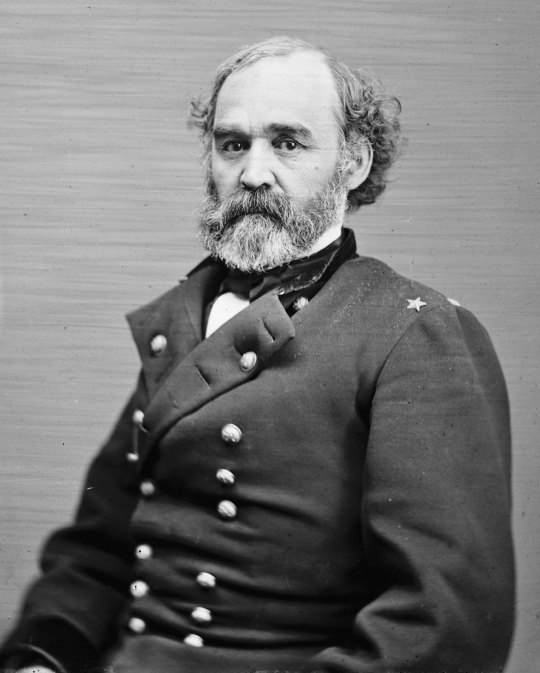

Montgomery C. Meigs, (born May 3, 1816, Augusta, Ga., U.S.—died Jan. 2, 1892, Washington, D.C.), U.S. engineer and architect, who, as quartermaster general of the Union Army during the American Civil War, was responsible for the purchase and distribution of vital supplies to Union troops. In the years before and after the war, he supervised the construction of numerous buildings and public works projects in the Washington, D.C., area.

After graduation from the University of Pennsylvania (1831) and the U.S. Military Academy (1836), Meigs was assigned to the Army corps of engineers. In this capacity he supervised several important government projects, including the construction of the wings and dome of the Capitol and the expansion of the General Post Office building. His most substantial contribution, however, was the Washington Aqueduct, which extended 12 miles (19 kilometres) from the Great Falls on the Potomac to a distribution reservoir west of Georgetown. His Cabin John Bridge (1852–60), designed to carry Washington’s main water supply and vehicular traffic, is an engineering masterpiece. Until the 20th century it was, at 220 feet, the longest single masonry arch in the world. As quartermaster general of the Union Army (1861–82), Meigs efficiently oversaw the disbursement of as much as $15,000,000,000 for the provisioning of troops during the Civil War. He also personally commanded the supplying of the armies of Grant and Sherman during several important campaigns in 1864 and early 1865.

Meigs’s best known architectural work in Washington, D.C.—undertaken after his official retirement—is the Old Pension Office Building (1883). The exterior is decorated with a terra-cotta frieze in low relief depicting Union forces in battle. The building’s enormous hall was used for the inaugural festivities of presidents Cleveland, Harrison, McKinley, Roosevelt, and Taft.

It was Meigs who suggested to Abraham Lincoln that Arlington would be an appropriate site for a national cemetery. Meigs himself is buried there.

#montgomery c meigs#american civil war#us civil war#civil war#history#meigs is one of my favsss#love reading about him#acw#unconditional queue

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

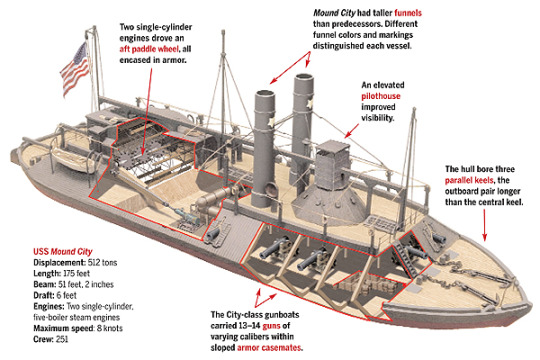

On Aug. 7, 1861, soon after the Union defeat at Manassas, Va., made it clear the Civil War would not end quickly, Union Quartermaster General Montgomery C. Meigs awarded engineer James B. Eads a contract to build seven armored gunboats for the Army’s Western Gunboat Flotilla. The City-class gunboats—designed by Eads, Commander John Rodgers and naval constructor John Lenthall and modified by Eads and naval architect Samuel M. Pook—were all commissioned by February 1862. “Pook’s Turtles,” as they were known, soon established themselves as the most powerful warships in the Western theater of operations.

The City-class gunboats differed only in detail. Mound City, whose specifications are listed in the illustration here, saw action along the Mississippi at Island No. 10, Fort Pillow/Plum Point Bend, Steeles Bayou, Grand Gulf and Vicksburg, as well as on the White and Red River campaigns. On May 10, 1862, off Fort Pillow, Confederate rams twice struck the Union gunship, which withdrew to shallow water and sank; Union shipwrights quickly returned it to service. During the bombardment of St. Charles, Ark., on June 17, 1862, a Rebel shore battery penetrated Mound City’s armor and steam drum, killing 125 of its crew and scalding another 25. Repaired once again, the gunboat served through war’s end and was decommissioned within weeks of the surrender at Appomattox.

0 notes

Text

Cemetery

A cemetery is a place in which dead human bodies and cremated remains are buried, usually with some form of marker to establish their identity. The term originates from the Greek κοιμητήριον, meaning sleeping place, and can include any large park or burial ground specifically intended for the deposit of the dead. Cemeteries in the Western world are also typically the place where the final ceremonies of death are observed, according to cultural practice or religious belief. Cemeteries are distinguished from other burial grounds by their location and are not usually adjoined to a church, as opposed to a "graveyard" which is located in a "churchyard," which includes any patch of land on church grounds. A public cemetery is made open for use by a surrounding community; a private cemetery is used only by a portion of the population or by a specific family group.

Contents

1 History

2 Establishments and regulations

3 Famous cemeteries worldwide

4 References

5 External Links

6 Credits

1.1 Cemetery reform

1.2 Military cemeteries

1.3 Later developments

2.1 Family cemeteries

A cemetery is generally a place of respect for the dead where the friends, descendants, and interested members of the public may visit to remember and honor those buried there. For many, it is also a place of spiritual significance, where the dead may visit from the afterlife, at least on occasion.

Green-Wood Cemetery, Brooklyn, New York

History

The grave of an infant at Horton, Northamptonshire.

The term cemetery was first used by early Christians and referred to a place for the Christian burial of the dead, often in Roman catacombs. The earliest cemetery sites can been traced back to the fifteenth century and have been found throughout Europe, Asia, and North America in Paleolithic caves and fields of prehistoric grave mounds, or barrows. Ancient Middle Eastern practices often involved the construction of graves grouped around religious temples and sanctuaries, while early Greek practices buried the dead along the roads leading to their cities.

Early burial grounds consisted of earthen graves, and were often unsightly and hasty places to dispose of the dead. European burial was customarily under the control of the church and took place on consecrated church ground. Though practices varied, in continental Europe, most bodies were buried in a mass grave until they had decomposed. The bones were then exhumed and stored in ossuaries either along the arcaded bounding walls of a cemetery or within the church, under floor slabs and behind walls.

The majority of fifteenth century Christian burial grounds became overcrowded and consequently unhealthy. The first Christian examples of cemeteries outside of a churchyard were founded by Protestants in response to overcrowded churchyards and the desire to physically and spiritually separate the dead from the living, a concept often intertwined with the Roman Catholic faith. Early cemetery establishments include Kassel (1526), Marburg (1530), Geneva (1536), and Edinburgh (1562). The structure of early individual grave sites often reflected the social class of the dead.

Cemetery reform

The formation of modern cemetery structures began in seventeenth century India when Europeans began burying their dead in cemetery structures and erecting vast monuments over the graves. Early examples have been found in Surat and Calcutta. In 1767, work on Calcutta’s South Park Street Cemetery was completed and included an intricate necropolis, or city of the dead, with streets of mausolea and magnificent monuments.

In the 1780s and 1790s similar examples were to be found in Paris, Vienna, Berlin, Dessau, and Belfast. The European elite often constructed chamber tombs within cemeteries for the stacking of family coffins. Some cemeteries also constructed a general receiving tomb for the temporary storage of bodies awaiting burial. In the early 1800s, European cities faced major structural reforms that included the restructuring of burial grounds. In 1804, for hygienic reasons, French authorities demanded that all public cemeteries be established outside city limits. Entrusted with a project to bury the dead in a way that was both respectful and hygienic, French architect Alexandre Brogniart designed a cemetery structure that included an English landscape-garden. The result, Mont-Louis Cemetery, would become world famous.

In 1829, similar work was completed on St. James Cemetery in Liverpool, designed to occupy a former quarry. In 1832 Glasgow’s Necropolis would follow. After the arrival of cholera in 1831, London was also forced to establish its first garden cemeteries, constructing Kensal Green in 1833, Norwood in 1837, Brompton in 1840, and Abney Park in 1840, all of which were meticulously landscaped and adorned with intricate architecture. Italian cemeteries followed a different design, incorporating a campo santo style which proved larger than medieval prototypes. Examples include Certosa at Bologna, designed in 1815, Brescia, designed in 1849, Verona, designed in 1828, and the Staglieno of Genoa, designed in 1851 and incorporating neoclassical galleries and an extensive rotunda.

Over time, all major European cities were equipped with at least one reputable cemetery. In larger and more cosmopolitan areas, such cemeteries included great architecture. U.S. cemeteries of similar structure included Boston’s Mount Auburn Cemetery, designed in 1831, Phildelphia’s Laurel Hill Cemetery, designed in 1839, and New York City’s Green-wood Cemetery, designed in 1838. Many southern U.S. cemeteries, such as those in New Orleans, favored above ground tomb structures due to strong French influence. In 1855, architect Andrew Downing suggested that cemetery monuments be constructed in such a way as to not interfere with cemetery maintenance; with this, the first "lawn cemetery" was constructed in Cincinnati, Ohio, a burial park equipped with memorial plaques installed flush with the cemetery ground.

Military cemeteries

Arlington National Cemetery, Washington D.C.

American military cemeteries developed out of the duty of commanders to care for their comrades, including those that had fallen. When the casualties of the American Civil War reached incomprehensible numbers, and hospitals and burial grounds overflowed with the bodies of the dead. General Montgomery Meigs proposed that more than 200 acres be taken from the estate of General Robert E. Lee for the purpose of burying the causalities of war. What followed was the development of Arlington National Cemetery, the first and most prestigious of war cemeteries to be erected on American soil. Today Arlington National Cemetery houses the bodies of those who died as active-duty members of the Armed forces, veterans retired from active military service, Presidents or former President of the United States, and any former member of the armed services who received a Medal of Honor, Distinguished Service Cross, Silver Star, or Purple Heart.

Other American military cemeteries include the Abraham Lincoln National Cemetery, the Gettysburg National Cemetery, the Knoxville National Cemetery and the Richmond National Cemetery. Internationally, military cemeteries include the Woodlands Cemetery near Stockholm (1917), the Slovene National Cemetery in Zale (1937), the San Cataldo Cemetery in Modena (1971), and the Cemetery for the Unknown in Hiroshima, Japan (2001).

Later developments

The change in cemetery structure sought to re-establish the "rest in peace" principle. Such aesthetic cemetery design contributed to the rise of professional landscape architects and inspired the making of grand public parks. At the turn of twentieth century, cremation offered a more popular, though in some places, controversial option to casket burial.

A "green burial" ground or "natural burial" ground is a type of cemetery which places a corpse into the soil to naturally decompose. The first of such cemeteries was created in 1993 at the Carlisle Cemetery in the United Kingdom. The corpse is prepared without traditional preservatives, and is buried in a biodegradable casket or cloth shroud. The graves of green burials are often minimally marked as to not interfere with the landscape of the cemetery. Some green cemeteries use natural markers such as shrubs or trees to denote a grave site. Green burials are posed as an environmentally friendly alternative to customary funeral practices.

Establishments and regulations

Internationally, the style of cemeteries has varied greatly. In the United States and many European countries, cemeteries may use tombstones placed in open spaces. In Russia, tombstones are usually placed in small fenced family lots. This was once a common practice in American cemeteries, and such fenced family plots can still be seen in some of the earliest American cemeteries constructed.

Cemeteries are not governed by laws that apply to real property, although most states have established laws that specifically apply to cemetery structures. Some common regulations require that each grave must be set apart, marked, and distinguished. Cemetery regulations are often required by departments of public health and welfare, and may prohibit future burials in existing cemeteries, enlargement of existing cemeteries, or the establishment of new ones.

Cemeteries in cities use valuable urban space, which may pose a significant problem within older cities. As historic cemeteries begin to reach their capacity for full burials, alternative memorialization, such as collective memorials for cremated individuals, became more common. Different cultures have different attitudes toward the destruction of cemeteries and subsequent use of the land for construction. In some countries it is considered normal to destroy the graves, while in others the graves are traditionally respected for a century or more. In many cases, after a suitable period of time has elapsed, the headstones are removed and the cemetery can be converted into a recreational park or construction site.

Trespassing against, vandalizing, or destruction of a cemetery or individual burial plot are considered criminal offenses, and can be prosecuted by the heirs of the involved plot. Large punitive damages, intended to deter further acts of desecration, may be awarded.

Family Cemeteries

A Buddhist graveyard. Kyoto, Japan.

In many cultures, the family is expected to provide the "final resting place" for their dead. Biblical accounts describe land owned by various important families for the burial of deceased family members. In Asian cultures, regarding their ancestors as having spirits who should be honored, families carefully selected the location for burial so as to keep their ancestors happy.

While uncommon today, family or private cemeteries were a matter of practicality during the settlement of America. If a municipal or religious cemetery was not established, settlers would seek out a small plot of land, often in wooded areas bordering their fields, to begin a family plot. Sometimes, several families would arrange to bury their dead together. While some of these sites later grew into true cemeteries, many were forgotten after a family moved away or died out. Groupings of tombstones, ranging from a few to a dozen or more, have on occasion been discovered on undeveloped land. Usually, little effort is made to remove remains when developing, as they may be hundreds of years old; as a result, the tombstones are often simply removed.

More recent is the practice of families with large estates choosing to create private cemeteries in the form of burial sites, monuments, crypts, or mausolea on their property; the mausoleum at architect Frank Lloyd Wright's Fallingwater is an example of this practice. Burial of a body at such a site may protect the location from redevelopment, such estates often being placed in the care of a trust or foundation. State regulations have made it increasingly difficult to start private cemeteries; many require a plan to care for the site in perpetuity. Private cemeteries are nearly always forbidden on incorporated residential zones.

Famous cemeteries worldwide

Père-Lachaise, Paris.

Since their eighteenth century reform, various cemeteries worldwide have served as international memorials, renowned for their meticulous landscaping and beautiful architecture. In addition to Arlington National Cemetery, other American masterpieces include Wilmington National Cemetery, Alexandria National Cemetery and the Gettysburg National Cemetery, a military park offering historic battlefield walks, living history tours, and an extensive visitor center.

Parisian cemeteries of great renown include the Père Lachaise, the world’s most visited cemetery. This cemetery was established by Napoleon in 1804, and houses the graves of Oscar Wilde, Richard Wright, Jim Morrison, and Auguste Comte among others. Paris is also home to the French Pantheon, completed in 1789. At the start of the French Revolution, the building was changed from a church into a mausoleum to hold the remains of noteworthy Frenchmen. The pantheon includes the graves of Jean Monnet, Victor Hugo, Alexandre Dumas, and Marie Curie.

London’s Abney Park, opened in 1840, is also an international place of interest. One of London’s seven magnificent cemeteries, it is based on the design of Arlington National Cemetery. The remaining magnificent seven include Kensal Green Cemetery, West Norwood Cemetery, Highgate cemetery, Nunhead Cemetery, Brompton Cemetery, and the Tower Hamlets Cemetery. England’s Brookwood Cemetery, also known as the London Necropolis, is also a cemetery of note. Established in 1852, it once was the largest cemetery in the world. Today more than 240,000 people have been buried there, including Margaret, Duchess of Argyll, John Singer Sargent, and Dodi Al-Fayed. The cemetery also includes the largest military cemetery in the United Kingdom. The ancient Egyptian Great Pyramid of Giza, marking the tomb of Egyptian Pharaoh Khufu, is also a well-known tourist attraction.

References

Curl, James Stevens. 2002. Death and Architecture. Gloucestershire: Sutton. ISBN 0750928778

Encyclopedia of U.S. History. Cemeteries. U.S. History Encyclopedia. Retrieved June 4, 2007.

Etlin, Richard A. 1984. The Architecture of Death. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Gale, Thomas. Cemeteries. Thomas Gale Law Encyclopedia. Retrieved June 4, 2007.

Oxford University Press. Cemetery. Dictionary of Architecture and Landscape Architecture. Retrieved June 4, 2007.

Worpole, Ken. 2004. Last Landscapes: The Architecture of the Cemetery in the West. Reaktion Books. ISBN 186189161X

External Links

All links retrieved January 23, 2017.

Cemeteries and Cemetery Symbols

London Cemetery Project: 130 cemeteries with high-quality photos.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats. The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

Cemetery history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

History of "Cemetery"

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

6 notes

·

View notes

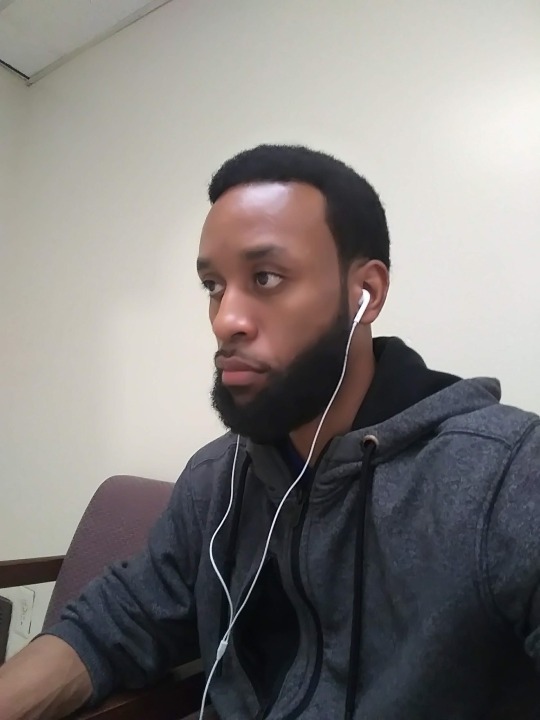

Photo

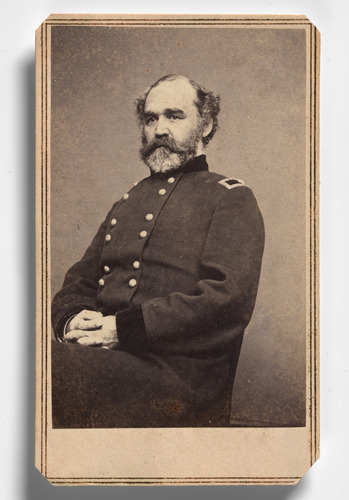

Montgomery Cunningham Meigs, Mathew Brady Studio, c. 1861, Smithsonian: National Portrait Gallery

Size: Image/Sheet: 8.5 x 5.4 cm (3 3/8 x 2 1/8")

Medium: Albumen silver print

https://npg.si.edu/object/npg_NPG.79.246.80

1 note

·

View note

Text

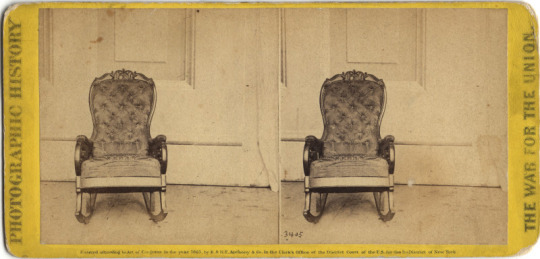

Take a Seat — The Lincoln Chairs

Chairs are such commonplace things—not usually thought of items in a collection of Abraham Lincoln’s documents, photographs, and artifacts. But the Lincoln Financial Foundation Collection holds several chairs and numerous files of information about chairs that have connections to the sixteenth president.

This cane-seated chair is made of rosewood, painted black with gold scroll work on its back and legs. Its open-work back is inlaid with mother of pearl and has a painted floral design on the center piece. According to Lincoln’s great-grandson Robert Lincoln Beckwith, who gifted the chair to the Lincoln collection in 1981, it was one of a set of chairs given to President Lincoln and used in the White House. A companion chair is held by the Lincoln Heritage Museum at Lincoln College in Lincoln, Illinois.

This solid oak Renaissance Revival style chair was originally designed by Montgomery C. Meigs in 1857 and manufactured by Bembe and Kimmel of New York for use in the U.S. House of Representatives. It and others like it were used in the House until 1859 when all were auctioned off to make way for new furniture. In 1863 the chair became part of the furnishings of Alexander Gardner’s newly opened photography studio in Washington, D.C. Abraham Lincoln was the studio’s the first customer and was first posed in this chair on November 8, 1863.

When James Ford, of the Ford’s Theatre in Washington, was notified on April 14, 1865, that President Lincoln would be attending the performance of Our American Cousin that night, he arranged for special furnishing of the VIP box above the stage that the president usually occupied. The furnishings included this red silk upholstered rocking chair. Lincoln was sitting in this chair when he was shot. After Lincoln’s death, the chair became a relic of the martyred president, and photographs like this one were widely circulated. The War Department held the chair as evidence during the trial of the assassination conspirators and then left it with the Smithsonian Institution, which ultimately returned the chair to Harry Ford’s widow. In 1929 she sold it at auction in New York, where automobile magnate and collector Henry Ford purchased it for $2,400. It is currently held by the Henry Ford Museum in Dearborn, Michigan.

This chair made of elk horns was presented to Lincoln at the White House on Saturday, November 26, 1864, by California hunter and trapper Seth Kinman. Fact and legend freely intermingle in stories about Kinman, who promoted himself as the archetypal frontiersman and toured the county entertaining crowds, selling photographs of himself, and exhibiting his frontier “curiosities.” In 1864 he traveled to the White House to meet Abraham Lincoln, present this chair, and entertain the president with tunes played on a fiddle made from the skull of his favorite mule. Over the years, Kinman also presented elk horn chairs to presidents James Buchanan, Andrew Johnson, and Rutherford Hayes. Lincoln was impressed enough by his chair that, a few weeks after receiving it, he claimed he would rather eat it antlers and all than to appoint a certain office-seeker.

In 1911, the Wanamaker department store of Philadelphia linked the Golden Jubilee of its founding with the 50th anniversary of Lincoln’s inauguration as president and advertised this “Abraham Lincoln Chair,” a replica of a chair owned by the Lincoln family when they lived in Springfield, Illinois. Wanamaker’s Lincoln chairs were available in solid mahogany or in birch painted ebony black with gold decoration. Prices ranged from $10 to $16.50. According to this advertisement, the chairs “will recall, many generations hence, tender memories of not only Abraham Lincoln, the beloved President, for whose memory and fame they are inspired, but also of The John Wanamaker Golden Jubilee, which celebration made them possible.”

8 notes

·

View notes

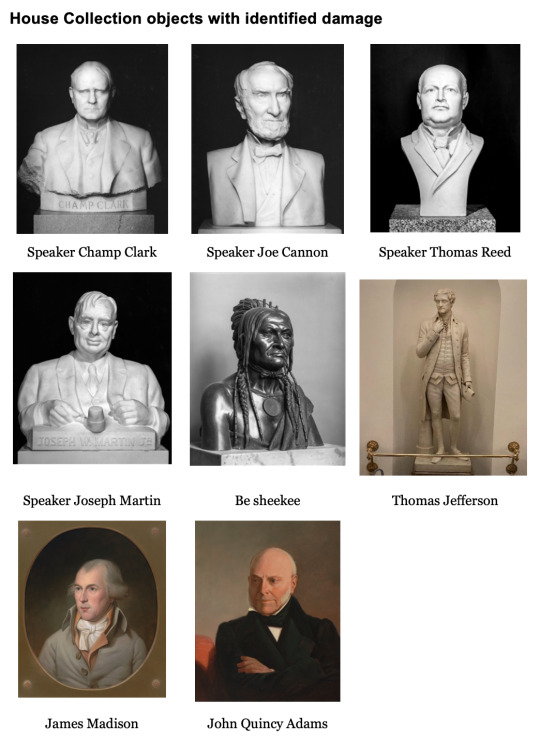

Text

Curators Seek $25,000 to Repair Artworks Damaged in U.S. Capitol Attack

https://sciencespies.com/history/curators-seek-25000-to-repair-artworks-damaged-in-u-s-capitol-attack/

Curators Seek $25,000 to Repair Artworks Damaged in U.S. Capitol Attack

When a far-right insurrectionist mob stormed the United States Capitol on January 6, lawmakers abruptly ended their session and fled to secure locations, many in fear for their lives. Dozens were injured that day, and five people, including a police officer who was beaten by rioters, died as a result of the attack.

In the wake of the insurrection, stories both heroic and insidious have revealed new insights on how those six hours of chaos unfolded. Now, reports Cristina Marcos for the Hill, Farar Elliott, a curator in the House of Representative’s Office of History and Preservation, and Architect of the Capitol J. Brett Blanton are shedding light on another aspect of the attack: namely, its toll on the building’s artworks.

As Elliott said in prepared testimony earlier this week, 535 of the 13,000 artifacts housed in the House’s art collections were on display throughout the Capitol complex on January 6.

“During the riot,” the curator told a House subcommittee, “courageous staffers saved several important artifacts.”

One quick-thinking clerk saved an 1819 silver inkstand, the oldest object in the legislative chamber. Staff also rescued the House’s ceremonial silver mace, which was created in 1841 to replace one destroyed when the British burned the Capitol in 1814—one of the only other times that the seat of government has faced violence of this magnitude, as Sarah Cascone points out for Artnet News.

All told, Elliott said, eight artworks—six sculptures and two paintings—were vandalized in the attack. Chemicals present in fire extinguishers, pepper spray, bear repellants, tear gas and other irritants used by rioters caused the majority of the damage. (Per Blanton’s testimony, staffers raced to the roof of the building to reverse airflows and try to limit the damage inflicted by these chemicals.) House curators have requested $25,000 in emergency funding to cover the costs of restoration and repair.

Assessing the damage

The morning after the riot, Capitol staff arrived on the scene to take stock of the damage. Per Blanton’s testimony, they found graffiti, shattered glass and debris from broken furniture, and blue paint tracked through the hallways, among other remnants of the violence. Two of the fourteen historic Frederick Law Olmsted lamps that decorate the Capitol grounds were “ripped from the ground,” Blanton said.

As Elliott testified, the artifacts featured in an ongoing exhibition about Joseph Rainey, the U.S.’ first black congressman, sustained no damage. The four giant John Trumbull paintings that grace the Capitol Rotunda and the fresco that decorates its ceiling, Apotheosis of Washington, also escaped the violence unscathed, reported Sarah Bahr for the New York Times in January.

Curators noted that some objects in the corridors adjacent to the House chamber doors were covered in a fine powder residue. The team collected samples of this powder from a marble bust of Speaker James Beauchamp “Champ” Clark and sent them to the Smithsonian’s Museum Conservation Institute, which identified the material as discharge from a nearby fire extinguisher. The residue contains yellow dye, silicone oil and other chemicals that could wreak long-lasting damage on the fragile historic objects, according to Elliott’s testimony.

The eight artifacts damaged included a painting of President James Madison and a bust of House Speaker Joseph W. Martin.

(Office of the Clerk, U.S. House of Representatives)

The artworks and their history

In a strange twist of fate, one of the damaged marble busts depicts a man involved in another violent incident at the Capitol: Speaker of the House Joseph W. Martin. The Massachusetts politician was on the House floor on March 1, 1954, when four Puerto Rican nationalists opened fire from the public viewing galleries, wounding five people. Martin declared Congress in recess as he took cover behind a marble pillar on the rostrum.

“Bullets whistled through the chamber in the wildest scene in the entire history of Congress,” the speaker later recalled.

Other damaged works included marble busts of Speaker Joseph Gurney Cannon and Speaker Thomas Reed, a bronze bust of Chippewa statesman Be sheekee, and a statue of Thomas Jefferson. Chemical traces also left residue on two painted portraits of presidents James Madison and John Quincy Adams, who is depicted in 1848, toward the end of his life. Curators placed all of the affected works beneath museum-grade plastic to prevent further damage.

Cannon, a Republican representative from Illinois known as “Uncle Joe,” wielded unprecedented power in the early 20th century as both chair of the Rules Committee and speaker. His influence was such that representative George Norris actually led a “revolt,” convincing members of both parties to strip Cannon of much of his power in 1910.

Be sheekee, a powerful Chippewa chief also called Buffalo or the Great Buffalo, is known for negotiating a land cessation treaty with the U.S. government. In 1855, he and 15 other Native Americans, including Aysh-ke-bah-ke-ko-zhay (or Flat Mouth), traveled from present-day Minnesota and Wisconsin to Washington, D.C. There, the leaders sat for Francis Vincenti, a little-known Italian sculptor. (The original Vincenti work resides in the U.S. Senate collections; this bust is an 1858 copy by Joseph Lasalle.)

Records show that Vincenti paid Be sheekee $5 for the sitting. Montgomery C. Meigs, an engineer who played a key role in the building and design of the Capitol Rotunda in the late 19th century, likely commissioned the portraits of the Native American men to send overseas as models for Thomas Crawford, an American sculptor working in Rome. Meigs had previously commissioned Crawford to sculpt the pediment for the Senate wing, The Progress of Civilization.

The Be sheekee bust numbers among the few representations of identifiable Native American figures on display in the Capitol. It also speaks to a fraught, painful history: During the era of Manifest Destiny, European colonizers continued to take land from Native groups through treaties or by force. At the same time, many European artists created likenesses of Native people according to their own fixed, racist stereotypes.

“[S]culptors of this period idealized Native Americans in their work and asserted that they were symbolic of the U.S. because they were uniquely American,” says Karen Lemmey, curator of sculpture at the Smithsonian American Art Museum (SAAM), in an email. “Meigs likely arranged for this portrait not because he wanted to commemorate Be sheekee as a sovereign leader, one who traveled to Washington to negotiate important matters on behalf of his people, but rather for its supposed ethnographic value as a record of a ‘vanishing race.’”

Lemmey adds, “One might see the portrait of Be sheekee as satisfying Meigs’s penchant for decorating the Capitol with things he and others regarded as authentically American.”

A worker sweeps up the dust and debris left behind by a white supremacist mob in the Rotunda of the U.S. Capitol building on January 7, 2021.

(Samuel Corum / Getty Images)

The road to recovery

As Blanton testified before the subcommittee on Wednesday, the “damage to our precious artwork and statues will require expert cleaning and conservation.”

But while the physical damage wrought by rioters will be fixed over time, the agency head added that the emotional damage will likely remain.

Overall, report Emily Cochrane and Luke Broadwater for the New York Times, Blanton said that the costs of increased mental health services for staff, reinforced security and building restorations will exceed $30 million.

In addition to damaging works of art, rioters left behind broken glass, blood, debris and enduring trauma for all involved. As Elvina Nawaguna and Kayla Epstein noted for Business Insider in January, a custodial staff comprised mostly of people of color was tasked with cleaning up the mess left behind by the overwhelmingly white rioters.

“One of the images that I’m haunted by is the black custodial staff cleaning up the mess left by that violent White supremacist mob. … That is a metaphor for America,” Congresswoman Ayanna Pressley told CNN’s Jake Tapper in early February. “We have been cleaning up after violent, white supremacist mobs for generations and it must end.”

#History

#02-2021 Science News#2021 Science News#Earth Environment#earth science#Environment and Nature#Nature Science#News Science Spies#Our Nature#outrageous acts of science#planetary science#Science#Science Channel#science documentary#Science News#Science Spies#Science Spies News#Space Physics & Nature#Space Science#History

0 notes

Text

3/12/21 8:53 Up It 8:54

3/12/21 7:45 ; 7:46 7:43 Up It 7:44 Clicking train-track noise 8:08 now 8:09 7:38 7:39 Up It

3/12/21 7:45 7:43 7:38

3/12/21 8:51

Up the caption at 8:52 - 8:53 - Horn In Town

3/12/21 8:51 Up It 8:52

3/12/21 7:46 ; Ipod keypad 7:44 7:45 7:37

3/12/21 7:47-7:46 ; 7:36

3/12/21 8:50 - 8:51

3/12/21 7:48-7:47

3/12/21 8:50

3/12/21 7:55 - 7:35

3/12/21 9:11 now 9:09

I only upped the caption at 9:11

3/12/21 9:09 Up It at 9:10 Robert Todd Lincoln - 🪵

3/12/21 7:55 to 7:56 - 7:35

3/12/21 8:00 to 8:01

3/12/21 8:03 8:04 now - 7:34

3/12/21 8:48 Up it 8:49

3/12/21 8:07

0 notes

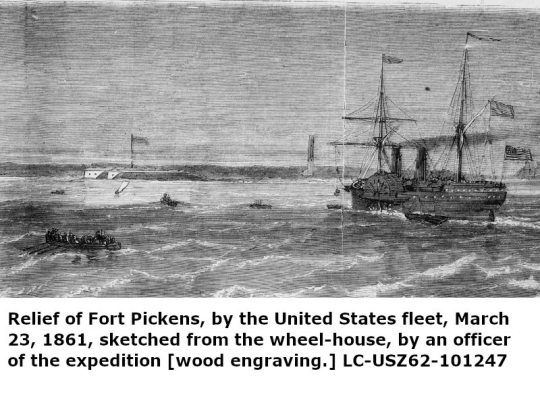

Photo

March 29, 1861, President Lincoln and Sec. Seward interview Capt. Montgomery C. Meigs on possibility of relieving Fort Pickens, Florida.***

At early morning cabinet meeting President announces decision to reinforce Fort Sumter, S.C. and Fort Pickens. [Source: The Lincoln Log]

***The fort was one of the few forts in the South that remained in Union hands throughout the American Civil War.

Glory for the Brave, Finalist in the Dr. Bob Rich Editing Contest

Amazon https://t2m.io/yKyvdj1X

kindle https://t2m.io/Uiw7XiiC

iBook https://t2m.io/BiwhKot6

Nook https://t2m.io/HPkXeCNb

Google Play https://t2m.io/7mrtgMrv

Kobo https://t2m.io/8m46203M

0 notes

Text

The Mystery of Lincoln’s First Inauguration Photograph

The Mystery of Lincoln’s First Inauguration Photograph

By Neely Tucker

Published November 20, 2019 at 10:00AM

This is a guest post by Adrienne M. Lundgren, senior photograph conservator in the Conservation Division.

Abraham Lincoln’s first inauguration on March 4, 1861, marked a pivotal moment in the nation’s history. A country on the brink of a civil war had all eyes looking to the new president as either the preserver of the nation or as an enemy of the South. Threats of assassination loomed; a plot had been discovered and narrowly averted a month earlier.

The photo taken of that moment has become an icon of U.S. history: Lincoln, a tiny dot in front of the unfinished Capitol Building; the faint slant of sunshine; the crowds crammed into every available vantage spot, including two men perched in a leafless tree. Here’s the New-York Tribune describing it: “The avenue in front of the portico was thronged with people, the crowd extending to a great distance on either side and reaching far into the Capitol grounds, and every available spot was black with human beings, boys and men clinging to the rails, mounting on fences, and climbing trees until they bent beneath their weight.”

Only three prints of this negative are known to survive. One is at the Library, a salted paper print kept in the Benjamin B. French album in the Prints and Photographs Division. (French headed the inauguration preparations.)

Lincoln’s first inauguration, March 4, 1861. Library conservator Adrienne Lundgren now believes the image was taken by government photographer James Wood. Prints and Photographs Division.

Alexander Gardner, then employed at Matthew Brady’s Washington gallery, is most often credited as the man behind the lens, though he never actually said that he was. Over time, it became attributed to him, which seemed reasonable. He took Lincoln’s portrait many times, he recorded some of the most lasting images of the Civil War and he photographed Lincoln’s second inauguration.

However, my recent research in the Library’s collections has shown that he did not take the historic image of the first inauguration. That photographer, instead, was the unheralded John Wood.

If you’ve never heard the name, don’t worry. He’s virtually unknown in American photography. If five of his images did not appear in “Gardner’s Photographic Sketch Book of the War,” he might not be mentioned at all.

But Wood was the government’s first official photographer. Montgomery C. Meigs, chief engineer for the capitol extension, hired him on May 14, 1856, to document major building projects in and around D.C. I first came across his work in 2016, while researching Civil War photographers who used their craft to make maps. After seeing Wood’s pictures of the Capitol construction, I was shocked that he had not earned a more prominent position in the annals of American photography. His work on architectural subjects was magnificent. His use of large formats, as large as 11 x 14 inches, also made him noteworthy.

Perhaps he isn’t widely known because he was a government photographer, a faceless bureaucrat of sorts. And while his views are captivating, they certainly were not profitable in a 19th century photographic marketplace focused largely on portraiture.

In any event, when I saw his photograph of the 1857 inauguration of James Buchanan, I was struck. It was taken from an elevated platform to the right of the president — just like the Lincoln inauguration photo. Further, I was able to identify Wood as the photographer of several other images in the French album.

Next, there’s the very paper it’s printed on — salted paper. This technique of printing was common in 1857, but by the time 1861 rolled around, Gardner and most other photographers had transitioned to albumen papers. Wood, however, was still using it. It was here that I began to think that the Lincoln photo might be by Wood, but I wasn’t at all sure.

Illustrated Times Weekly, April 6, 1861, from photo by “Mr. J. Wood.” Manuscript Division.

The proof came after a year of searching. In the April 6, 1861, edition of the Illustrated Times, a British weekly, I located a woodcut engraving that was almost an exact match of the famous photograph. The caption: “Inauguration of the Hon. Abraham Lincoln, as President of the United States, at Washington, on March 4, 1861 — (From a photograph by Mr. J. Wood.)” The woodcut took a few artistic liberties, such as making Lincoln prominent and filling in the blurred American flag, but the rest is exact. Remember the newspaper story describing men climbing trees to get a better view? Compare the two in the lower left corner. As with so many other details, it’s a precise match.

Lastly, this photograph was clearly taken from an elevated platform, meaning the photographer had privileged access. It makes sense that this honor would be given to the Capitol’s official photographer, who had worked the previous inauguration from much the same vantage point. The New-York Tribune story confirms there was such a platform: “A small camera was directly in front of Mr. Lincoln, another at a distance of a hundred yards, a third of huge dimensions on his right, raised on a platform built especially for the purpose.”

News reports mention a camera about 100 yards away from the portico; this is likely it. From the Montgomery C. Meigs papers. Manuscript Division.

Wood did indeed work with a large camera. And so it’s my conviction that it was him on the platform that day, opening the shutter for two or three seconds, the light streaming onto a collodion glass plate negative, preserving the image of a man, and a nation, poised on the precipice of a new world order.

These early photographers deserve our consideration, and it gives me great pleasure to bring another one of them who was lost in the shadows back into the light.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

Read more on https://loc.gov

0 notes

Photo

Shout out to Meigs for having an A+ beard, look at that thing. The quatermaster general knew what was up

#my ramblings#montgomery c meigs#look at it the thing is just perfect#it's not too long and it's full....i approve#also shoutout for basically labelling his name with anything he built#my dude knew what he was doing lol#acw#history

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

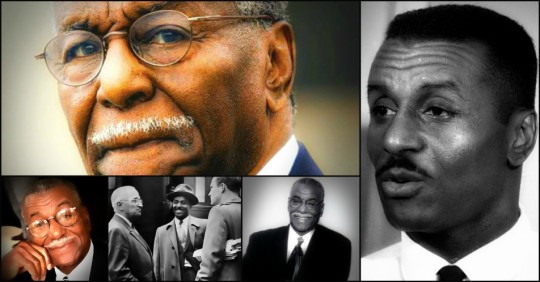

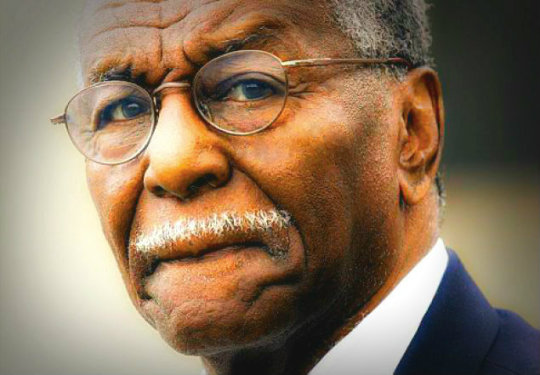

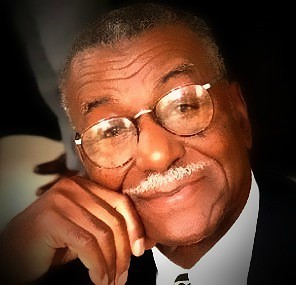

Fred Shuttlesworth

Frederick Lee "Fred" Shuttlesworth ( born Fred Lee Robinson, March 18, 1922 – October 5, 2011), was a U.S. civil rights activist who led the fight against segregation and other forms of racism as a minister in Birmingham, Alabama. He was a co-founder of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, initiated and was instrumental in the 1963 Birmingham Campaign, and continued to work against racism and for alleviation of the problems of the homeless in Cincinnati, Ohio, where he took up a pastorate in 1961. He returned to Birmingham after his retirement in 2007. He helped Martin Luther King Jr. during the Civil Rights Movement.

The Birmingham-Shuttlesworth International Airport was named in his honor in 2008.

Early life

Born in Mount Meigs, Alabama, Shuttlesworth became pastor of the Bethel Baptist Church in Birmingham in 1953 and was Membership Chairman of the Alabama state chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in 1956, when the State of Alabama formally outlawed it from operating within the state. In May 1956 Shuttlesworth and Ed Gardner established the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights to take up the work formerly done by the NAACP.

The ACMHR raised almost all of its funds from local sources at mass meetings. It used both litigation and direct action to pursue its goals. When the authorities ignored the ACMHR's demand that the City hire black police officers, the organization sued. Similarly, when the United States Supreme Court ruled in December 1956 that bus segregation in Montgomery, Alabama, was unconstitutional, Shuttlesworth announced that the ACMHR would challenge segregation laws in Birmingham on December 26, 1956.

On December 25, 1956, unknown persons tried to kill Shuttlesworth by placing sixteen sticks of dynamite under his bedroom window. Shuttlesworth somehow escaped unhurt even though his house was heavily damaged. A police officer, who also belonged to the Ku Klux Klan, told Shuttlesworth as he came out of his home, "If I were you I'd get out of town as quick as I could". Shuttlesworth told him to tell the Klan that he was not leaving and "I wasn't raised to run."

Southern Christian Leadership Conference

In 1957 Shuttlesworth, along with Martin Luther King Jr., Ralph Abernathy from Montgomery, Joseph Lowery from Mobile, Alabama, T. J. Jemison from Baton Rouge, Louisiana, Charles Kenzie Steele from Tallahassee, Florida, A. L. Davis from New Orleans, Louisiana, Bayard Rustin and Ella Baker founded the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. The SCLC adopted a motto to underscore its commitment to nonviolence: "Not one hair of one head of one person should be harmed."

Shuttlesworth embraced that philosophy, even though his own personality was combative, headstrong and sometimes blunt-spoken to the point that he frequently antagonized his colleagues in the Civil Rights Movement as well as his opponents. He was not shy in asking King to take a more active role in leading the fight against segregation and warning that history would not look kindly on those who gave "flowery speeches" but did not act on them. He alienated some members of his congregation by devoting as much time as he did to the movement at the expense of weddings, funerals, and other ordinary church functions.

As a result, in 1961 Shuttlesworth moved to Cincinnati, Ohio, to take up the pastorage of the Revelation Baptist Church. He remained intensely involved in the Birmingham campaign after moving to Cincinnati, and frequently returned to help lead actions.

Shuttlesworth was apparently personally fearless, even though he was aware of the risks he ran. Other committed activists were scared off or mystified by his willingness to accept the risk of death. Shuttlesworth himself vowed to "kill segregation or be killed by it".

Murder attempts

When Shuttlesworth and his wife Ruby attempted to enroll their children in a previously all-white public school in Birmingham in 1957, a mob of Klansmen attacked them, with the police nowhere to be seen. His assailants included Bobby Frank Cherry, who six years later was involved in the 16th Street Baptist Church Bombing. The mob beat Shuttlesworth with chains and brass knuckles in the street while someone stabbed his wife. Shuttlesworth drove himself and his wife to the hospital where he told his kids to always forgive.

In 1958, Shuttlesworth survived another attempt on his life. A church member standing guard saw a bomb and quickly moved it to the street before it went off.

The Freedom Rides

Shuttlesworth participated in the sit-ins against segregated lunch counters in 1960 and took part in the organization and completion of the Freedom Rides in 1961.

Shuttlesworth originally warned that Alabama was extremely volatile when he was consulted before the Freedom Rides began. Shuttlesworth noted that he respected the courage of the activists proposing the Rides but that he felt other actions could be taken to accelerate the Civil Rights Movement that would be less dangerous. However, the planners of the Rides were undeterred and decided to continue preparing.

After it became certain that the Freedom Rides were to be carried out, Shuttlesworth worked with the Congress of Racial Equality to organize the Rides and became engaged with ensuring the success of the rides, especially during their stint in Alabama. Shuttlesworth mobilized some of his fellow clergy to assist the rides. After the Riders were badly beaten and nearly killed in Birmingham and Anniston during the Rides, he sent deacons to pick up the Riders from a hospital in Anniston. He himself had been brutalized earlier in the day and had faced down the threat of being thrown out of the hospital by the hospital superintendent. Shuttlesworth took in the Freedom Riders at the Bethel Baptist Church, allowing them to recuperate after the violence that had occurred earlier in the day.

The violence in Anniston and Birmingham almost led to a quick end to the Freedom Rides. However, the actions of supporters like Shuttlesworth gave James Farmer, the leader of C.O.R.E., which had originally organized the Freedom Rides, and other activists the courage to press forward. After the violence that occurred in Alabama but before the Freedom Riders could move on, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy gave Shuttlesworth his personal phone number in case the Freedom Riders needed federal support.

When Shuttlesworth prepared the Riders to leave Birmingham and they reached the Greyhound Terminal, the Riders found themselves stranded as no bus driver was willing to drive the controversial group into Mississippi. Shuttlesworth stuck with the Riders and called Kennedy. Prompted by Shuttlesworth, Kennedy tried to find a replacement bus driver. Unfortunately, his efforts eventually proved unsuccessful. The Riders then decided to take a plane to New Orleans (where they had planned on finishing the Rides) and were assisted by Shuttlesworth in getting to the airport and onto the plane.

Shuttlesworth’s commitment to the Freedom Rides was highlighted by Diane Nash, a student activist in the Nashville Student Movement and a major organizer of the later waves of Rides. Nash noted, "Fred was practically a legend. I think it was important – for me, definitely, and for a city of people who were carrying on a movement – for there to be somebody that really represented strength, and that’s certainly what Fred did. He would not back down, and you could count on it. He would not sell out, [and] you could count on that." The students involved in the Rides appreciated Shuttlesworth's commitment to the principles of the Freedom Rides – ending the segregationist laws of the Jim Crow South. Shuttlesworth's fervent passion for equality made him a role model to many of the Riders.

Project C

Shuttlesworth invited SCLC and King to come to Birmingham in 1963 to lead the campaign to desegregate it through mass demonstrations–what Shuttlesworth called "Project C", the "C" standing for "confrontation". While Shuttlesworth was willing to negotiate with political and business leaders for peaceful abandonment of segregation, he believed, with good reason, that they would not take any steps that they were not forced to take. He suspected their promises could not be trusted until they acted on them.

One of the 1963 demonstrations he led resulted in Shuttlesworth's being convicted of parading without a permit from the City Commission. On appeals the case reached the US Supreme Court. In its 1969 decision of Shuttlesworth v. Birmingham, the Supreme Court reversed Shuttlesworth's conviction, determining that circumstances indicated that the parade permit was denied not to control traffic, as the state contended, but to censor ideas.

In 1963 Shuttlesworth was set on provoking a crisis that would force the authorities and business leaders to recalculate the cost of segregation. This occurred when James Bevel, SCLC's Director of Direct Action and Director of Nonviolent Education, initiated and organized the young students of the city to stand up for their rights. This plan was helped immeasurably by Eugene "Bull" Connor, the Commissioner of Public Safety and the most powerful public official in Birmingham, who used Klan groups to heighten violence against blacks in the city. Even as the business class was beginning to see the end of segregation, Connor was determined to maintain it. While Connor's direct police tactics intimidated black citizens of Birmingham, they also created a split between Connor and the business leaders. They resented both the damage Connor was doing to Birmingham's image around the world and his high-handed attitude toward them.

Similarly, while Connor may have benefited politically in the short run from Shuttlesworth's and Bevel's determined provocations, they also fit into Shuttleworth's long-term plans. The televised images of Connor's directing handlers of police dogs to attack young unarmed demonstrators and firefighters' using hoses to knock down children had a profound effect on American citizens' view of the civil rights struggle, and helped lead to the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Shuttlesworth's activities were not limited to Birmingham. In 1964 he traveled to St. Augustine, Florida (which he often cited as the place where the civil rights struggle met with the most violent resistance), taking part in marches and widely publicized beach wade-ins.

In 1965 he was active in the Selma Voting Rights Movement, and its march from Selma to Montgomery which led to the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Shuttlesworth thus played a role in the efforts that led to the passage of the two great legislative accomplishments of the Civil Rights Movement. In later years he took part in commemorative activities in Selma at the time of the anniversary of the famous march. And he returned to St. Augustine in 2004 to take part in a celebration of the fortieth anniversary of the St. Augustine movement there.

1966-2006: After the Voting Rights Act

Shuttlesworth organized the Greater New Light Baptist Church in 1966.

In 1978, Shuttlesworth was portrayed by Roger Robinson in the television miniseries King.

Shuttlesworth founded the "Shuttlesworth Housing Foundation" in 1988 to assist families who might otherwise be unable to buy their own homes.

In 1998 Shuttlesworth became an early signer and supporter of the Birmingham Pledge, a grassroots community commitment to combating racism and prejudice. It has since then been used for programs in all fifty states and in more than twenty countries.

On January 8, 2001, he was presented with the Presidential Citizens Medal by President Bill Clinton. Named President of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference in August 2004, he resigned later in the year, complaining that "deceit, mistrust and a lack of spiritual discipline and truth have eaten at the core of this once-hallowed organization".

In 2004, Shuttlesworth received the Award for Greatest Public Service Benefiting the Disadvantaged, an award given out annually by Jefferson Awards.

During the 2004 election that overturned a city charter provision that prohibited Cincinnati's City Council from adopting any gay-rights ordinance, Shuttlesworth voiced advertisements urging voters to reject the repeal, saying "The thing that I disagree with is when gay people ... equate civil rights, what we did in the '50s and '60s, with special rights ... I think what they propose is special rights. Sexual rights is not the same as civil rights and human rights."

Family

Although he was born Freddie Lee Robinson, Shuttlesworth took the name of his stepfather, William N. Shuttlesworth.

Shuttlesworth was married to Ruby Keeler Shuttlesworth, with whom he had four children: Patricia Shuttlesworth Massengill, Ruby Shuttlesworth Bester, Fred L. Shuttlesworth Jr., and Carolyn Shuttlesworth. The Shuttleworths divorced in 1970, and Ruby died the following year.

Shuttlesworth married Sephira Bailey in 2007.

After retirement

Prompted by the removal of a non-cancerous brain tumor in August of the previous year, he gave his final sermon in front of 300 people at the Greater New Light Baptist Church on March 19, 2006—the weekend of his 84th birthday. He and his second wife, Sephira, moved to downtown Birmingham where he was receiving medical treatment.

On July 16, 2008, the Birmingham, Alabama, Airport Authority approved changing the name of the Birmingham's airport in honor of Shuttlesworth. On October 27, 2008, the airport was officially changed to Birmingham-Shuttlesworth International Airport.

On October 5, 2011, Shuttlesworth died at the age of 89 in his hometown of Birmingham, Alabama. The Birmingham Civil Rights Institute announced that it intends to include Shuttlesworth's burial site on the Civil Rights History Trail. By order of Alabama governor Robert Bentley, flags on state government buildings were to be lowered to half-staff until Shuttlesworth's interment.

He is buried in the Oak Hill Cemetery in Birmingham.

Wikipedia

6 notes

·

View notes

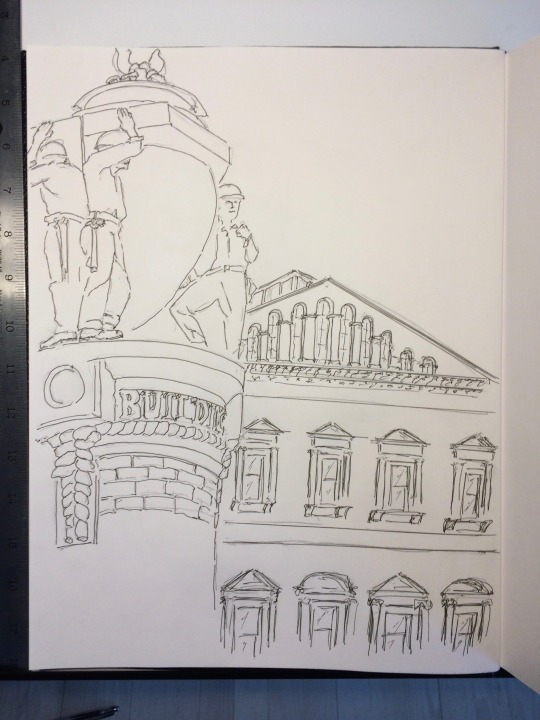

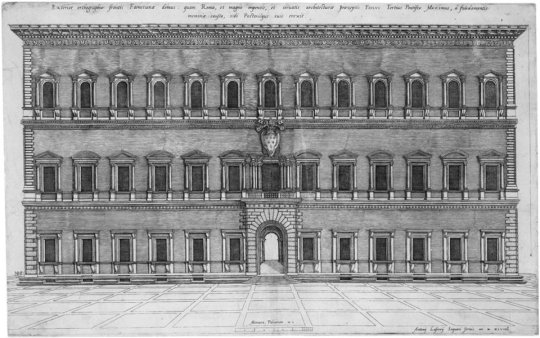

Photo

Ink & Pencil - The National Building Museum

The National Building Museum is housed in the former Pension Bureau building, a brick structure completed in 1887 and designed by Montgomery C. Meigs, the U.S. Army quartermaster general. It is notable for several architectural features, including the spectacular interior columns and a frieze, sculpted by Caspar Buberl, stretching around the exterior of the building and depicting Civil War soldiers in scenes somewhat reminiscent of those on Trajan's Column as well as the Horsemen Frieze of the Parthenon. (Although the Museum's exterior was actually modeled after the Palazzo Farnese in Rome).

But its harder to find information on the Museum’s main Sculpture that stands outside the Pensions Building (see below).

Its monumental, but I am not a fan. (I think it looks a bit Nazi or Soviet!) Still it begged to be included in the drawing.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Fort Jefferson - The massive coastal fortress in Garden Key

Fort Jefferson – The massive coastal fortress in Garden Key

Construction of Fort Jefferson was begun on Garden Key in December 1846, under the supervision of 2nd Lt. Horatio Wright, after plans drawn up by Lt. Montgomery C. Meigs were approved in November. Meigs’ plans were based on a design by Joseph Totten.

The building covers 16 acres. It is the largest brick masonry structure in the Americas, and is composed of over 16 million bricks. Fort Jefferson…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Video

youtube

See YouTube video of Janet Kuypers reading her poems "Vase of Tulips" (written on National Tulip Day), "Quartermaster General, Burying Bodies" (written on the day of the beginning of the Civil War, from the perspective of Montgomery C. Meigs), and "Only Nineteen" (written on her 19-year wedding anniversary) 5/18/19 while she hosted "Poetry Aloud" (this video was filmed from a Panasonic Lumix 2500 camera).

0 notes

Photo

The Quartermaster: Montgomery C. Meigs, Lincoln's General, Master Builder of the Union Army by Robert O'Harrow Jr. Narrated by Tom Perkins. I am recommending this book to my non-fiction book discussion group. I've listened to many good books about the Civil War, and this #Audible book tells a story from a different perspective. General Meigs is an unsung hero. Could the Union have won without Meigs? Read the book before you answer the question. (at Port Of Kingston) https://www.instagram.com/p/BrLqsjKleES/?utm_source=ig_tumblr_share&igshid=1apmrg64pnlfy

0 notes

Text

Breaking News: Arlington Cemetery, Nearly Full, May Become More Exclusive

New Post has been published on https://www.thisdaynews.net/2018/05/29/breaking-news-arlington-cemetery-nearly-full-may-become-more-exclusive/

Breaking News: Arlington Cemetery, Nearly Full, May Become More Exclusive

ARLINGTON, Va. — The solemn ritual of a burial with military honors is repeated dozens of times a day, in foul weather or fair, at Arlington National Cemetery, honoring service members from privates to presidents. But in order to preserve the tradition of burial at the nation’s foremost military cemetery for future generations, the Army, which runs Arlington, says that it may have to deny it to nearly all veterans who are living today.

Arlington is running out of room. Already the final resting place for more that 420,000 veterans and their relatives, the cemetery has been adding about 7,000 more each year. At that rate, even if the last rinds of open ground around its edges are put to use, the cemetery will be completely full in about 25 years.

“We’re literally up against a wall,” said Barbara Lewandrowski, a spokeswoman for the cemetery, as she stood in the soggy grass where marble markers march up to the stone wall separating the grounds from a six-lane highway. Even that wall has been put to use, stacked three high with niches for cremated remains.

The Army wants to keep Arlington going for at least another 150 years, but with no room to grow — the grounds are hemmed in by highways and development — the only way to do so is to significantly tighten the rules for who can be buried there. That has prompted a difficult debate over what Arlington means to the nation and how to balance egalitarian ideals against the site’s physical limits.

The strictest proposal the Army is considering would allow burials only for service members killed in action or awarded the military’s highest decoration for heroism, the Medal of Honor. Under those restrictions, Arlington would probably conduct fewer burials in a year than it does right now in a single week.

A policy like that would exclude thousands of currently eligible combat veterans and career officers who risked their lives in the service and who planned to be buried in Arlington among their fallen comrades.

“I don’t know if it’s fair to go back on a promise to an entire population of veterans,” said John Towles, a legislative deputy director for Veterans of Foreign Wars who deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan. The group, with 1.7 million veterans, has adamantly opposed the new restrictions.

“Let Arlington fill up with people who have served their country,” said Mr. Towles, who is eligible under current rules because he was wounded in battle. “We can create a new cemetery that, in time, will be just as special.”

Arlington is not the only place for military burials, of course. There are 135 national cemeteries maintained by the Department of Veterans Affairs across the country. But Arlington is by far the most prominent, and curtailing burial there would mean changing the site from an active cemetery into something closer to a museum.

The Army is conducting a survey of public opinion on the question through the summer, and expects to make formal recommendations in the fall.

“What does the nation want us to do?” Arlington’s executive director, Karen Durham-Aguilera, said in an interview. “If the nation has the will to say we want to keep Arlington special and available, we have to make a change.”

In a fitting turn of history, the cemetery now faced with a threat of overcrowding was created to address overcrowding. Early in the Civil War, the heavy death toll in battles near the capital soon filled Washington’s existing cemeteries. Desperate for more burial space, the Quartermaster General of the Army, Montgomery C. Meigs, turned to a rolling green plantation just across the Potomac — the home of Gen. Robert E. Lee, whose decision to fight on the Confederate side marked him as a traitor in many Union eyes.

General Meigs’s men began burying corpses beneath simple wood markers in the fields, and then, in a grim rebuke to the absent owner, lined the flower garden with the graves of Union officers and built a tomb near the door of the plantation house to hold the bones of 2,100 unknown dead.

At first, Arlington was anything but a coveted resting place. Most early burials were of ordinary soldiers whose families could not afford to have their remains shipped home. But as revered Union officers later chose to be buried in Arlington among the troops, the cemetery rose in prestige. The Tomb of the Unknowns was erected after World War I, and on nearly every Memorial Day since then, the sitting president has laid a wreath there.

Among the limestone rows are milestones of human progress: The first explorer to map the Grand Canyon, the first person killed in an airplane crash, the first astronauts to die trying to reach space. Some distinguished themselves on the battlefield, others in later life, including Albert Sabin, who served briefly as a wartime Army doctor and went on to develop a polio vaccine, and Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., a wounded Civil War lieutenant of little distinction who later became a Supreme Court justice. Most would have been barred under restrictions now being contemplated by the Army.

The modern concept of Arlington — an egalitarian Elysian field where generals and G.I.’s of every creed and color are buried side by side — did not truly emerge until the cemetery was desegregated after World War II, according to Micki McElya, a history professor at the University of Connecticut who has written about the cemetery.

“Many look to the place as a self-evident case for national inclusion and belonging, as an expression of the many and diverse become one,” Professor McElya said in an interview. That, she said, is the Arlington cited by Khizr Khan, the father of an Army captain killed in Iraq and buried at the cemetery, when he urged Donald J. Trump to visit.

“Look at the graves of brave patriots who died defending the United States of America,” Mr. Khan said in his speech at the 2016 Democratic National Convention. “You will see all faiths, genders, and ethnicities.”

Now, though, that all-inclusive idea is bumping up against the lack of space.

Arlington has tried to stretch what room it has. It ended the old practice of burying family members side by side, and now stacks them two or three deep in a single plot. In sections that hold only cremated remains, the rows are now spaced closer together. But planners say those measures can do only so much.

Under current rules, burial plots in Arlington are open to veterans who served long enough to retire from the military; to troops who were wounded in battle or received one of the three highest awards for valor; to prisoners of war; to troops who die while on active duty; and to a few civilians who serve in high-level government posts. Their spouses and dependents are also eligible.

The Army has laid out several proposals for changing those rules to keep Arlington open longer, but only the most restrictive options would make much difference — and those are the least popular among veterans.

“Everybody wants to see Arlington stay open,” said Gerardo Avila, a wounded Iraq veteran who spoke to Congress on the issue on behalf of the American Legion. He said that while he would gladly give up his own spot to ensure a place for a future Medal of Honor recipient, the Legion, with 2.3 million members, does not share that view.

“You are voting your own rights away,” he said. “I’m not sure our members are willing to do that.”

Army surveys indicate that the public supports giving priority to troops killed in battle or awarded the Medal of Honor. But it is not hard to find graves in Arlington of arguably deserving men and women who did neither.

On a recent evening, Nadine McLachlan knelt before the grave of her husband, Col. Joseph McLachlan, to trim the grass with scissors before arranging a bright vase of lilies. Colonel McLachlan was a fighter pilot who strafed the beaches of Normandy on D-Day; a week after the invasion, he was shot down and, though wounded, made his way back through enemy lines to safety. He went on to fly more than 100 more missions, earning the Legion of Merit, the Distinguished Flying Cross and 17 Air Medals for acts of heroism in flight.

He survived the war and lived for six more decades, until 2005. So under the most restrictive proposals, he would not qualify for burial at Arlington.

“My Joe was a wonderful man — very courageous, very kind,” Ms. McLachlan said. “I’m not sure that’s fair, to cut out men like him. They were in the line of fire, even if they made it. Being buried here with his friends meant a lot to him. It really is a dilemma.”

0 notes