#moral re-armament movement

Text

Confession in the Unification Church

MUST LISTEN: The "Cult of Confession" episode of Blessed Child podcast

One Twitter user @kijinosu describes this episode and its content:

"In this podcast, Renee describes a feature of thought reform that I hadn't seen elsewhere in my yet brief studies. Let me label it the Big Brother effect and put it out for discussion. Listen to ‘Cult of Confession with Renee'. I call it the Big Brother effect because, as I understand it, UC's incessant report-contact-consult practice combined with group confession causes the believer to feel that they are always being watched. In response to this feeling of always being watched, the believer creates a god that covers all of the demands of the collective. Because satisfying this god then satisifes all of the collective's demands, the believer focuses just on this god. The end result is self-reinforcing thought reform that is less dependent of the collective for maintenance.”

Confession in the Unification Church

Moon and Kwak on repentance, October 1989:

Each one of us needs heavenly wisdom to solve the problem of our own burden. To be able to live a lifestyle in which we can confess and report things to a central figure can only bring us great fortune.

Hyo Nam Kim (Dae Mo Nim) on March 9, 2002:

In the Divine Principle, is there anything written about the removal of Original sin? In the first, original Blessings, to qualify we had to confess all of our sins and repent and accept pardon as part of the condition to receive the Blessing. Yet, from 6000 Couples Blessing on, our sins were forgiven upon easier and easier conditions. Father would say, subsequently, "I will not ask about your past... just repent and recommit..."

Sun Myung Moon on April 26, 1992:

"Even now you sometimes sneak a drink. Father understands this very well, these secret drinks taste the best. Raise your hands if you sneak a drink sometimes. If you do not confess, it will carry over to the Spirit World."

From the Interview and Confession Form for BC Matching/Blessing Applicants:

It is the responsibility of your District Director (or the designated church leader or STF Director), representing the Continental Director and True Parents, to make sure that you understand the value of the Blessing and that you are prepared and qualified to attend. This confidential meeting is also your opportunity to confess any sins and perhaps receive guidance so that you can go into the Blessing with a clean conscience, free from accusation. Sin came into this world through the fall and cut us off from God, therefore it is important to confess your sins. Do not try to hide your mistakes because they will eventually come out and cause even more pain. The confession pages will stay confidentially with a representative of the Blessing Department. All three pages must be submitted to the Blessing Department.

Conference with [Black] Heung Jin Nim - Takeru Kamiyama (1987)

Before he came to New York in November 1987, I had heard many stories about his new existence in the body of a black African young man, traveling around and hearing confessions. I wondered, how can this brother really be [Black] Heung Jin Nim? Members all over the world are claiming that [Black] Heung Jin Nim has spoken through them, but how can we know if he really did?

Black Heung Jin Nim in DC by Damian Anderson

"With my own eyes, I saw this man in the Washington DC church knock people’s heads together, hit them viciously with a baseball bat, smack them around the head, punch them, and handcuff them with golden handcuffs. I had seen enough. Todd Lindsay was the first to leave. His wife was due to have a baby any day. My wife was six months pregnant at the time, and we were next in line for “confession” to the heavy-handed inquisitor."

Heung Jin Nim’s Spiritual Work by Michael Mickler:

These lectures, punctuated by songs and testimonies or sometimes lively jumping and marching, also took hours, and there was no provision for sleep during the three days. Food also was not a problem since most members were placed on fasting conditions following their confessions. Heung Jin Nim showed special concern for infertile couples and called for couples willing to give birth to a child for them to adopt. There were “tears streaming from many eyes” as “the giving and receiving couples embraced with deep emotion.” At the close of each conference, “participants were given a detailed schedule for their…lives of devotion and attendance,” including time for morning and evening prayers and for study and discussion of the Principle. Many members experienced personal liberation. Public confession or confession with one’s spouse was a prominent feature of “Black” Heung Jin Nim’s conferences. They could unburden themselves of deeply held secrets and “separate from Satan.” Within an intensely supportive environment, they could repent, make restitution as needed, and have a “second chance” to become pure. Others achieved levels of spiritual intimacy, which had been lacking.

On the MRA’s use of confession

Encyclopedia.com on Frank Buchman’s use of confession in the Oxford Group Movement:

He organized his followers into small groups where participants could confess their sins and share their religious experiences in an intimate setting; members would then seek to convert others through one-onone evangelism. Buchman's followers listened for God's plans for their lives, and measured their behavior through a moral code centered on absolute honesty, purity, unselfishness, and love (the Four Absolutes). During the 1920s Buchman developed an international network of these small groups that became known as the Oxford Group Movement.

Encyclopedia.com on Frank Buchman’s use of confession in the Moral Re-Armament Movement:

In 1938 he announced the campaign for Moral Rearmament (MRA), offering Christianity as an alternative to both communism and fascism. In the late 1930s MRA sought to prevent war by calling individuals on each side to confess their sins to the other and adhere to the Four Absolutes. During World War II it turned its energies to morale building, especially in industrial relations. MRA saw Christianity and communism as the world's two competing ideologies; during the Cold War it sought to defend the West, primarily by focusing on labor peace, strong families, and moral values. Through the 1950s the movement held international rallies and used the media skillfully; it achieved prominence by publicizing the involvement of world leaders, especially from the United States, the British Commonwealth, and Asia.

#Moral Rearmament Movement#moral re-armament movement#frank buchman#oxford group#confessions#black heung jin#cleophas kundioni#cleophas#moonies#unification church#unification theology

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

By Alan Watts

“Supposing that I say to you each one of you is really the great self, and you say well, if all you’ve said up to now makes me fairly sympathetic to this intellectually, but I don’t really feel it, What must I do to feel it really?

My answer to you is this; you ask me that question because you don’t want to feel it really. You are frightened of it. And therefore what you are going to do, it’s you are going to get a method of practice so that you can put it off. So that I can say, well, I can be a long time on the way getting this thing. And then maybe I’ll be worthy of it after I have suffered enough, because we are brought up in a social scheme, whereby we have to deserve what we get, and the price that one pays for all good things is suffering, all of that is precisely postponement. One is afraid here and now to see it. If you had the nerve, the real nerve you would see it right away. Only that would be there when one feels you shouldn’t have nerve like that, that would be awful, that wouldn’t do at all. After all I’m supposed to be poor little me, and I’m not really much of a muchness. I’m playing the role of being poor little me. And therefore in order to be something great, like a Buddha or a jivamokta. One liberated in this life, I ought to suffer for it. So you can suffer for it. There are all kinds of ways invented for you to do this. And you can discipline yourself. You can gain control of your mind, and you can do all sorts of extraordinary things. I mean you can drink water in through your rectum, and do the most fantastic things. But that’s just like being able to run the hundred yards in nine seconds, or any other kind of accomplishment you want to engage in. absolutely nothing to do with the realization of the self.

The realization of the self is fundamentally depends on coming off it. When we say to people who put on some kind of an act, “Oh come off it.” And some people can come off it. They laugh and say they suddenly realize they are making fools of themselves, and they laugh at themselves and they come off it. So in exactly the same way, the guru, the teacher is trying to make you come off it. If he finds he can’t make you come off it, he is going to put you through all these exercises. So that you at the last time when you’ve got enough discipline, and enough suffering and enough frustration, you’ll give it all up and realize you were there for the beginning, and there was nothing to realize.

So this tremendous schizophrenia in human beings, of thinking that they are rider and horse, soul in command of body, or will in command of passions wrestling with them. All that kind of split thinking simply aggravates the problem. And we get more and more split. So we have all sorts of people engaged in an interior conflict, which they will never resolve. Because the true self, either you know it or you don’t. If you do know it, then you know it’s the only one. And the other, so called lower self, just ceases to be a problem. It becomes something like a mirage, and you don’t’ go around hitting at mirages with a stick, or trying to put reigns on them. You just know that they are mirages and walk straight through them. That split is implanted in us all. And because of our being split minded we are always dithering. Is the choice that I’m about to make of the higher self or of the lower self? Is it of the spirit, or is it of the flesh? Is the word that I received of the lord, or is it of the devil? And nobody can decide. If you knew how to choose, you wouldn’t have to.

In the so called moral re-armament movement, you test your messages that you get from god in your quiet time, by comparing them with standards of absolute honesty, absolute purity, absolute love, and so on. If you knew what those things were, you wouldn’t have to test. You would know immediately. And do you know what those things are? The more one thinks about the question, “What would absolute love be?” supposing I could set myself the ideal of being absolutely loving to everybody. What would that imply in terms of conduct? You can think about that until all is blue, because you could never get to the answer. The problems of life are so subtle, that to try to solve them with vague principles, as if those vague principles were specific instructions is completely impossible.

It is important to overcome split-mindedness. But what is the way? Where can you start from if you’re already split? A Taoist saying is that, when the wrong man uses the right means, the right means work in the wrong way. So what are you to do? How can you get off it and get moving?

If I say to you, “good morning”, you say, “good morning, nice day isn’t it?” Or if I hit you, boom you say, “ouch!” you don’t stop to hesitate to give these answers or responses. You can’t think about it when I say “good morning,” in exactly the same way, that kind of response, which doesn’t have to be a deliberate response, a response of a no-deliberating mind, is a response of a Buddha-mind or an unattached-mind. But you must not imagine that this is necessarily a quick response. If you get hung up on the idea of responding quickly, the idea of quickness will be, itself a form of obstruction.

When you are perfectly free to feel stuck or not stuck, then you are unstuck. Nothing can stick on the real mind. And you will find this out if you watch the flow of your thoughts. And those thoughts arise and go like waves on the water. They come and go, when they go, they are as if they had never been here. There is process. There is the flow of thought,

The flow of thought doesn’t have to happen to anyone. Experience does not have to beat upon an experiencer. There is, all the time, simply the one stream going on. And we are convinced that we stand aside from it and observe it. We’ve been brought up that way.

It’s very important to get rid of that illusion of duality between the thinker and the thought. Find out who is the thinker behind the thoughts? Who is the real, genuine you?”

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kwame Nkrumah on the methods of neo-colonialism (from Neo-Colonialism, the Last Stage of Imperialism):

Some of these methods used by neo-colonialists to slip past our guard must now be examined. The first is retention by the departing colonialists of various kinds of privileges which infringe on our sovereignty: that of setting up military bases or stationing troops in former colonies and the supplying of ‘advisers’ of one sort or another. Sometimes a number of ‘rights’ are demanded: land concessions, prospecting rights for minerals and/or oil; the ‘right’ to collect customs, to carry out administration, to issue paper money; to be exempt from customs duties and/or taxes for expatriate enterprises; and, above all, the ‘right’ to provide ‘aid’. Also demanded and granted are privileges in the cultural field; that Western information services be exclusive; and that those from socialist countries be excluded.

Even the cinema stories of fabulous Hollywood are loaded. One has only to listen to the cheers of an African audience as Hollywood’s heroes slaughter red Indians or Asiatics to understand the effectiveness of this weapon. For, in the developing continents, where the colonialist heritage has left a vast majority still illiterate, even the smallest child gets the message contained in the blood and thunder stories emanating from California. And along with murder and the Wild West goes an incessant barrage of anti-socialist propaganda, in which the trade union man, the revolutionary, or the man of dark skin is generally cast as the villain, while the policeman, the gum-shoe, the Federal agent — in a word, the CIA — type spy is ever the hero. Here, truly, is the ideological under-belly of those political murders which so often use local people as their instruments.

While Hollywood takes care of fiction, the enormous monopoly press, together with the outflow of slick, clever, expensive magazines, attends to what it chooses to call ‘news. Within separate countries, one or two news agencies control the news handouts, so that a deadly uniformity is achieved, regardless of the number of separate newspapers or magazines; while internationally, the financial preponderance of the United States is felt more and more through its foreign correspondents and offices abroad, as well as through its influence over inter-national capitalist journalism. Under this guise, a flood of anti-liberation propaganda emanates from the capital cities of the West, directed against China, Vietnam, Indonesia, Algeria, Ghana and all countries which hack out their own independent path to freedom. Prejudice is rife. For example, wherever there is armed struggle against the forces of reaction, the nationalists are referred to as rebels, terrorists, or frequently ‘communist terrorists'!

Perhaps one of the most insidious methods of the neo-colonialists is evangelism. Following the liberation movement there has been a veritable riptide of religious sects, the overwhelming majority of them American. Typical of these are Jehovah’s Witnesses who recently created trouble in certain developing countries by busily teaching their citizens not to salute the new national flags. ‘Religion’ was too thin to smother the outcry that arose against this activity, and a temporary lull followed. But the number of evangelists continues to grow.

Yet even evangelism and the cinema are only two twigs on a much bigger tree. Dating from the end of 1961, the U.S. has actively developed a huge ideological plan for invading the so-called Third World, utilising all its facilities from press and radio to Peace Corps.

During 1962 and 1963 a number of international conferences to this end were held in several places, such as Nicosia in Cyprus, San Jose in Costa Rica, and Lagos in Nigeria. Participants included the CIA, the U.S. Information Agency (USIA), the Pentagon, the International Development Agency, the Peace Corps and others. Programmes were drawn up which included the systematic use of U.S. citizens abroad in virtual intelligence activities and propaganda work. Methods of recruiting political agents and of forcing ‘alliances’ with the U.S.A. were worked out. At the centre of its programmes lay the demand for an absolute U.S. monopoly in the field of propaganda, as well as for counteracting any independent efforts by developing states in the realm of information.

The United States sought, and still seeks, with considerable success, to co-ordinate on the basis of its own strategy the propaganda activities of all Western countries. In October 1961, a conference of NATO countries was held in Rome to discuss problems of psychological warfare. It appealed for the organisation of combined ideological operations in Afro-Asian countries by all participants.

In May and June 1962 a seminar was convened by the U.S. in Vienna on ideological warfare. It adopted a secret decision to engage in a propaganda offensive against the developing countries along lines laid down by the U.S.A. It was agreed that NATO propaganda agencies would, in practice if not in the public eye, keep in close contact with U.S. Embassies in their respective countries.

Among instruments of such Western psychological warfare are numbered the intelligence agencies of Western countries headed by those of the United States ‘Invisible Government’. But most significant among them all are Moral Re-Armament QARA), the Peace Corps and the United States Information Agency (USIA).

Moral Re-Armament is an organisation founded in 1938 by the American, Frank Buchman. In the last days before the second world war, it advocated the appeasement of Hitler, often extolling Himmler, the Gestapo chief. In Africa, MRA incursions began at the end of World War II. Against the big anti-colonial upsurge that followed victory in 1945, MRA spent millions advocating collaboration between the forces oppressing the African peoples and those same peoples. It is not without significance that Moise Tshombe and Joseph Kasavubu of Congo (Leopoldville) are both MRA supporters. George Seldes, in his book One Thousand Americans, characterised MRA as a fascist organisation ‘subsidised by . . . Fascists, and with a long record of collaboration with Fascists the world over. . . .’ This description is supported by the active participation in MRA of people like General Carpentier, former commander of NATO land forces, and General Ho Ying-chin, one of Chiang Kai-shek’s top generals. To cap this, several newspapers, some of them in the Western ;vorld, have claimed that MRA is actually subsidised by the CIA.

When MRA’s influence began to fail, some new instrument to cover the ideological arena was desired. It came in the establishment of the American Peace Corps in 1961 by President John Kennedy, with Sargent Shriver, Jr., his brother-in-law, in charge. Shriver, a millionaire who made his pile in land speculation in Chicago, was also known as the friend, confidant and co-worker of the former head of the Central Intelligence Agency, Allen Dulles. These two had worked together in both the Office of Strategic Services, U.S. war-time intelligence agency, and in the CIA.

Shriver’s record makes a mockery of President Kennedy’s alleged instruction to Shriver to ‘keep the CIA out of the Peace Corps’. So does the fact that, although the Peace Corps is advertised as a voluntary organisation, all its members are carefully screened by the U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI).

Since its creation in 1961, members of the Peace Corps have been exposed and expelled from many African, Middle Eastern and Asian countries for acts of subversion or prejudice. Indonesia, Tanzania, the Philippines, and even pro-West countries like Turkey and Iran, have complained of its activities.

However, perhaps the chief executor of U.S. psychological warfare is the United States Information Agency (USIA). Even for the wealthiest nation on earth, the U.S. lavishes an unusual amount of men, materials and money on this vehicle for its neo-colonial aims.

The USIA is staffed by some 12,000 persons to the tune of more than $130 million a year. It has more than seventy editorial staffs working on publications abroad. Of its network comprising 110 radio stations, 60 are outside the U.S. Programmes are broadcast for Africa by American stations in Morocco, Eritrea, Liberia, Crete, and Barcelona, Spain, as well as from off-shore stations on American ships. In Africa alone, the USIA transmits about thirty territorial and national radio programmes whose content glorifies the U.S. while attempting to discredit countries with an independent foreign policy.

The USIA boasts more than 120 branches in about 100 countries, 50 of which are in Africa alone. It has 250 centres in foreign countries, each of which is usually associated with a library. It employs about 200 cinemas and 8,000 projectors which draw upon its nearly 300 film libraries.

This agency is directed by a central body which operates in the name of the U.S. President, planning and coordinating its activities in close touch with the Pentagon, CIA and other Cold War agencies, including even armed forces intelligence centres.

In developing countries, the USIA actively tries to prevent expansion of national media of information so as itself to capture the market-place of ideas. It spends huge sums for publication and distribution of about sixty newspapers and magazines in Africa, Asia and Latin America.

The American government backs the USIA through direct pressures on developing nations. To ensure its agency a complete monopoly in propaganda, for instance, many agreements for economic co-operation offered by the U.S. include a demand that Americans be granted preferential rights to disseminate information. At the same time, in trying to close the new nations to other sources of information, it employs other pressures. For instance, after agreeing to set up USIA information centres in their countries, both Togo and Congo (Leopoldville) originally hoped to follow a non-aligned path and permit Russian information centres as a balance. But Washington threatened to stop all aid, thereby forcing these two countries to renounce their plan.

Unbiased studies of the USIA by such authorities as Dr R. Holt of Princeton University, Retired Colonel R. Van de Velde, former intelligence agents Murril Dayer, Wilson Dizard and others, have all called attention to the close ties between this agency and U.S. Intelligence. For example, Deputy Director Donald M. Wilson was a political intelligence agent in the U.S. Army. Assistant Director for Europe, Joseph Philips, was a successful espionage agent in several Eastern European countries.

Some USIA duties further expose its nature as a top intelligence arm of the U.S. imperialists. In the first place, it is expected to analyse the situation in each country, making recommendations to its Embassy, thereby to its Government, about changes that can tip the local balance in U.S. favour. Secondly, it organises networks of monitors for radio broadcasts and telephone conversations, while recruiting informers from government offices. It also hires people to distribute U.S. propaganda. Thirdly, it collects secret information with special reference to defence and economy, as a means of eliminating its international military and economic competitors. Fourthly, it buys its way into local publications to influence their policies, of which Latin America furnishes numerous examples. It has been active in bribing public figures, for example in Kenya and Tunisia. Finally, it finances, directs and often supplies with arms all anti-neutralist forces in the developing countries, witness Tshombe in Congo (Leopoldville) and Pak Hung Ji in South Korea. In a word, with virtually unlimited finances, there seems no bounds to its inventiveness in subversion.

One of the most recent developments in neo-colonialist strategy is the suggested establishment of a Businessmen Corps which will, like the Peace Corps, act in developing countries. In an article on ‘U.S. Intelligence and the Monopolies’ in International Affairs (Moscow, January 1965), V. Chernyavsky writes: ‘There can hardly be any doubt that this Corps is a new U.S. intelligence organisation created on the initiative of the American monopolies to use Big Business for espionage. It is by no means unusual for U.S. Intelligence to set up its own business firms which are merely thinly disguised espionage centres. For example, according to Chernyavsky, the C.I.A. has set up a firm in Taiwan known as Western Enterprises Inc. Under this cover it sends spies and saboteurs to South China. The New Asia Trading Company, a CIA firm in India, has also helped to camouflage U.S. intelligence agents operating in South-east Asia.

Such is the catalogue of neo-colonialism’s activities and methods in our time. Upon reading it, the faint-hearted might come to feel that they must give up in despair before such an array of apparent power and seemingly inexhaustible resources.

Fortunately, however, history furnishes innumerable proofs of one of its own major laws; that the budding future is always stronger than the withering past. This has been amply demonstrated during every major revolution throughout history.

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Death and Life of Punk, the Last Subculture, by Dylan Clark

Punk is dead. Long live punk. (graffito in use since 1970s)

Punk had to die so that it could live.

With the death of punk, classical subcultures died. What had, by the 1870s, emerged as ‘subcultures’ were understood to be groups of youths who practised a wide array of social dissent through shared behavioural, musical, and costume orientations. Such groups were remarkably capable vehicles for social change, and were involved in dramatically reshaping social norms in many parts of the world. These ‘classical’ subcultures obtained their potency partly through an ability to shock and dismay, to disobey prescribed confines of class, gender, and ethnicity. But things changed. People gradually became acclimatized to such subcultural transgressions to the point that, in many places, they have become an expected part of the social landscape. The image of rebellion has become one of the most dominant narratives of the corporate capitalist landscape: the ‘bad boy’ has been reconfigured as a prototypical consumer. And so it was a new culture in the 1970s, the punk subculture, which emerged to fight even the normalization of subculture itself, with brilliant new forms of social critique and style. But even punk was caught, caged, and placed in the subcultural zoo, on display for all to see. Torn from its societal jungle adn safely taunted by viewers behind barcodes, punk, the last subculture, was dead.

The classical subculture ‘died’ when it became the object of social inspection and nostalgia, and when it became so amenable to commodification. Marketers long ago awakened to the fact that subcultures are expedient vehicles for selling music, cars, clothing, cosmetics, and everything else under the sun. but this truism is not lost on many subcultural youth themselves, and they will be the first to grumble that there is nothing new under the subcultural sun.

In this climate, constrained by the discourse of subculture, deviation from the norm ain’t what it used to be. Deviation from the norm seems, well, normal. It is allegedly common for a young person to choose a prefab subculture off the rack, wear it for a few years, then rejoin with the ‘mainstream’ culture that they never really left at all. Perhaps the result of our autopsy will show that subculture (of the young, dissident, costumed kind) has become a useful part of the status quo, and less useful for harbouring discontent. For these reasons we can melodramatically pronounce that subculture is dead.

Yet still they come: goths, neo-hippies, and ‘77-ish mohawked punk rockers. And still people find solidarity, revolt, and individuality by inhabiting a shared costume marking their membership in a subculture. And still parents get upset, people gawk, peers shudder, and selves are recreated. Perhaps it is cruel or inaccurate to call these classical motifs dead, because they can be so very alive and real to the people who occupy them. Like squatters in abandoned buildings, practising subcultists give life to what seem to be deceased structures.

Or is the subculture dead? The death of subculture-- that is, the death of subcultural autonomy and meaningful rebellion-- did not escape the notice of many. For decades people have decried the commercialization of style, the paisley without the politics. But such laments have not failed to produce strategies. There is something else-- another kind of subculture, gestating and growing far below the classical subcultural terrain. For two decades thousands kept a secret: punk never died. Instead, punk had, even in its earliest days, begun to articulate a social form that anticipates and outmanoeuvres the dominance of corporate-capitalism. And as the Cold War finally disappears from decades of habit, and as the political and cultural hegemony of corporate-capitalism seems unrivalled, it suddenly becomes clear that the anarchist frameworks of punk have spread into all sorts of social groupings. The social forms punks began to play with in the early 1970s have penetrated subcultures across the spectrum. After the death of the classical subculture we witness the birth of new practices, ideologies, and ways of being-- a vast litter of anarchism.

For tribes of contemporary people who might be called punk (and who often refuse to label themselves), their subculture is partly in revolt from the popular discourse of subculture, from what has become, in punk eyes, a commercialized form of safe, affected discontent-- a series of consumed subjectivities, including pre-fabricated ‘Alternative’ looks. Punk is, ironically, a subculture operating within parts of that established discourse, and yet it is also a subculture partly dedicated to opposing what the discourse of subculture has become. As the century rolls over, punk is the invention of not just new subjectivities but, perhaps, a new kind of cultural formation. The death of subculture has in some ways helped to produce one of the most formidable subcultures yet: the death of subculture is the (re)birth of punk.

Part I. Classical Punk: The Last Subculture

Consumer voyeurism is much more offensive to punk sensibilities than song themes about addiction or slaughtering dolls onstage. (Van Dorston 1990)

At the heart of early punk was calculated anger. It was anger at the establishment and anger at the allegedly soft rebellion of the hippie counterculture; anger, too, at the commodification of rock and roll (Cullen 1996:249). Its politics were avowedly apolitical, yet it openly and explicitly confronted the traditions and norms of the powers that be. Describing the cultural milieu for young people in 19765, Greil Marcus notes the centrality of cultural production: ‘For the young everything flowed from rock ‘n’ roll (fashion, slang, sexual styles, drug habits, poses), or was organized by it, or was validated by it’ (Marcus 1989:53). But by the early 1970s, with commodification in full swing, with some artists said to have compromised their integrity by becoming rich stars,a dn with ‘rock’ having been integrated into the mainstream, some people felt that youth subcultures were increasingly a part of the intensifying consumer society, rather than opponents of the mainstream. Punk promised to build a scene that could not be taken. Its anger, pleasures, and ugliness were to go beyond what capitalism and bourgeois society could swallow. It would be untouchable, undesirable, unmanageable.

Early punk was a proclamation and an embrace of discord. In England it was begun by working-class youths decrying a declining economy and rising unemployment, chiding the hypocrisy of the rich, and refuting the notion of reform. In America, early punk was a middle-class youth movement, a reaction against the boredom of mainstream culture (Henry 1989:69). Early punk sought to tear apart consumer goods, royalty, and sociability; and it sought to destroy the idols of the bourgeoisie.

At first punk succeeded beyond its own lurid dreams. The Sex Pistols created a fresh moral panic fuelled by British tabloids, Members of Parliament, and plenty of everyday folk. Initially, at least, they threatened ‘everything England stands for’: patriotism, class hierarchy, ‘common decency’ and ‘good taste.’ When the Sex Pistols topped the charts in Britain, and climbed high in America, Canada, and elsewhere, punk savoured a moment in the sun: every public castigation only convinced more people that punk was real.

Damming God and the state, work and leisure, home and family, sex and play, the audience and itself, the music briefly made it possible to experience all those things as if they were not natural facts but ideological constructs: things than had been made and therefore could be altered, or done away with altogether. It became possible to see these things as bad jokes, and for the music to come forth as a better joke. (Marcus 1989:6)

Punk was to cross the rubicon of style from which there could be no retreat. Some punks went so far as to valorize anything mainstream society disliked, including rape and death camps; some punks slid into fascism. When the raw forces and ugliness of punk succumbed to corporate-capitalism within a few short years, the music/style nexus had lost its battle of Waterloo. Punk waged an all-out battle on this front, and it wielded new and shocking armaments, but in the end, even punk was proven profitable. Penny Rimbaud (1998:74) traces its cooption:

Within six months the movement had been bought out. The capitalist counter-revolutionaries had killed with cash. Punk degenerated from being a force for change, to becoming just another element in the grand media circus. Sold out, sanitised and strangled, punk had become just another social commodity, a burnt-out memory of how it might have been.

Profits serve to bandage the wounds inflicted by subcultures, while time and nostalgia cover over the historical stars. Even punk, when reduced to a neat mohawk hairstyle and a studded leather jacket, could be made into a cleaned-up spokesman for potato chips. Suddenly, the language of punk was rendered meaningless. Or perhaps-- perhaps-- the meaningless language of punk was made meaningful. Greil Marcus (1989:438) records the collapse of punk transgression: ‘the times changed, the context in which all these things could communicate not pedantry but novelty vanished, and what once were metaphors became fugitive footnotes to a text no longer in print.’

Like their subcultural predecessors, early punks were too dependent on music and fashion as modes for expression; these proved to be easy targets for corporate cooptation. ‘The English punk rock rhetoric of revolution, destruction, and anarchy was articulated by means of specific pleasures of consumption requiring the full industrial operations that were ostensibly were the objects of critique’ (Shank 1994: 94). Tactically speaking, the decisive subcultural advantage in music and style-- their innovation, rebellion, and capacity to alarm--was preempted by the new culture industry, which mass-produced and sterilized punk’s verve. With the collapse of punk’s stylistic ultimatum, what had been the foundations for twentieth-century subcultural dissent were diminished--not lost, but never to completely recover the power they once had in music and style.

Part II. The Triumph of the Culture Industry

Gil Scott Heron is famous for the line, ‘The Revolution will not be televised’. But in a way the opposite has happened. Nothing’s given the change to brew and develop anymore, before the media takes hold of it and grinds it to death. Also, there’s an instant commodification of everything that might develop into something ‘revolutionary.’ (Dishwater Pete, quoted in Vale 1997:17)

Having ostensibly neutralized early punk, the culture indsutry proved itself capable of marketing any classical youth subculture. All styles, musics, and poses could be packaged: seemingly no subculture was immune to its gaze. So levelled, classical subcultures were deprived of some of their ability to generate meaning and voice critique.

‘Subculture,’ in the discourse handed down to the present, has come popularly to represent youths who adorn themselves in tribal makeup and listen to narrow genres of music. Subcultures are, in this hegemonic caricature, a temporary phase through which mostly juvenile, mostly ‘White,’ and mostly harmless people symbolically create identity and peer groups, only to later return, as adults, to their pre-ordained roles in mainstream society.

The aforementioned idea of subculture is not without merit: ti is often a temporary vehicle through which teens and young adults select a somewhat prefabricated identification, make friends, separate from their parents, and individuate themselves. As a social form, this classical breed of subculture is important, widespread, and diversely expressed. In this form ‘subculture’ is partly a response to prevailing political economies and partly a cultural pattern that has been shaped and reworked by subcultures themselves and by the mass media. As such it is an inherited social form, and one which is heavily interactive with capitalist enterprise. Thus, subculture is both a discourse that continues to be a meaningful tool for countless people and, at the same time, something of a pawn of the culture industry.

With its capacity to designate all subcultures, all youth, under a smooth frosting of sameness, the culture industry was capable of violating the dignity of subcultists and softening their critique. Implied in the culture industry’s appropriation of subcultural imagery was the accusation of sameness, of predictability, of a generic ‘kids will be kids.’ To paste on any group a label of synchronic oneness is, in some way, to echo colonial tactics. ‘Youths’ or ‘kids,’ when smothered with a pan-generational movement of discontent, are reduced to a mere footnote to the dominant narrative of corporate-capitalism. Trapped in nostalgia and commercial classifications, subcultures and youth are merged into the endless, amalgamated consumer culture.

No wonder, then, that subcultural styles no longer provoke panics, except in select small towns. Piercings and tattoos might cause their owner to be rejected from a job, but they generally fail to arouse astonishment or fear. Writes Frederic Jameson (1983:124): ‘there is very little in either the form of the content of contemporary art that contemporary society finds intolerable and scandalous. The most offensive forms of this art-punk rock, say...are all taken in stride by society’. So too, ideas of self gratification are no longer at odds with the status quo. In the ‘Just Do It’ culture of the late twentieth century, selfish hedonism dominates the airwaves. Says Simon Reynolds (1988:254): ‘“Youth” has been co-opted, in a sanitized, censored version...Desire is no longer antagonistic to materialism, as it was circa the Stones’ “Satisfaction”.’ Instead young people often relate to the alienation of The Smiths or REM, who seem to lament that ‘everyone is having fun except me’; the sense of failure at not having the ‘sex/fun/style’ of the young people in the mass media. Indeed, long before ‘satisfaction’ became hegemonic, the commodity promised to satisfy. But because it cannot satisfy it leaves a melancholy that is satisfiable only in further consumption. So notes Stacy Corngold (1996:33) who concludes that ‘Gramsci’s general point appears to have been confirmed: all complex industrial societies rule by non-coercive coercion, whereby political questions become disguised as cultural ones and as such become insoluble.’ Youth subcultures, after the triumph of the culture industry, may perpetually find themselves one commodity short of satisfaction, and trapped by words that were once liberatory.

Or, as Grant McCracken (1988:133) argues, commodities cannot be completely effective as a mode of dissent because they are made legible in a language written by corporate-capitalism. As he writes:

when “hippies,” “punks”, “gays”, “feminists”, “young republicans”, and other radical groups use consumer goods to declare their difference, the code they use renders them comprehensible to the rest of society and assimilable within a larger set of cultural categories...The act of protest is finally an act of participation in a set of shared symbols and meanings.

Though McCracken underestimates the efficacy of stylized dissent, he is able to locate a defining weakness in the emphasis that subcultures have historically placed in style. My contention is that style was far more potent as a mode of rebellion in the past, and that not until the demise of punk was subcultural style dealt a mortal wound. After the demise of punk’s uber-style, after a kind of terminal point for outrageousness, there is a banality to subcultural style. And it is for this reason that Dick Hebdige’s (1979:102) ‘communication of a significant difference’ can no longer serve as a cornerstone in the masonry of subcultural identity. Following this logic, George McKay (1998:20) comments on the ‘Ecstasy Industry’ of mass culture, which has seized control of style. Thus

The Ecstasy Industry, for its part, is doing only too well under contemporary capitalism and could easily absorb the techniques of lifestyle anarchists to enhance a marketably naughty image. The counterculture that once shocked the bourgeoisie with its long hair, beards, dress, sexual freedom, and art has long since been upstaged by bourgeois entrepreneurs.

We can say, too, that the economy for subcultural codes suffers from hyper-inflation. In other words, the value of subcultural signs and meanings has been depleted: an unusual hairstyle just can’t buy the outsider status it used to. Stylistic transgressions are sometimes piled on one another like so many pesos, but the value slips away almost instantly. Thus, by the 1990s, dissident youth subcultures were far less able to arouse moral panics (Boethius 1995:52) despite an accelerated pace of style innovation (Ferrell 1993:194). In the 2000s, subcultural style is worth less because a succession of subcultures has been commodified in past decades. ‘Subculture’ has become a billion-dollar industry. Bare skin, odd piercings, and bluejeans are not a source of moral panics these days: they often help to create new market opportunities. Even irony, indifference, and apathy toward styles and subculture have been incorporated into Sprite and OK Cola commercials: every subjectivity, or so it may seem, has been swallowed up by the gluttons of Madison Avenue (Frank 1996, 1997a, 1997b).

Part III. The Discourse of Subculture, Plain for All to See

We burrow and borrow and barrow (or dump) our trash and treasures in an endless ballet of making and unmaking and remaking. The speed of this process is now such that a child can see it. (McLuhan and Nevitt 1972:104-5)

The patterned quality of youth subculture (innovate style and music → obtain a following → become commodified and typecast) forms a discourse of subculture, one that is recognized by academics and youths alike. That such a discourse is identifiable over several decades, however, does not mean that it goes unchanged or unchallenged. As a social form it undergoes change in its own right, but also because it has become the discursive object of the mass media. In particular, ‘subculture’ has been in many ways incorporated as a set trope of the culture industries which retail entertainment, clothing, and other commodities. Many observers-- academics, journalists, and culture industrialists-- fail to recognize that hegemonic appropriation of the discourse of subculture has had impacts for the people in subcultures.

Observers may fall into a classic pitfall, wherein they typecast subcultures. Any number of scholars are guilty of detailing the patterned quality of the discourse of subculture, trapping subcultures in a kind of synchronic Othering. One example should suffice:

Nowhere is the rapidly cyclical nature of rock-and-roll history more evident than in the series of events surrounding punk rock. Punk broke all the rolls and declared war on all previously existing musical trends and rules of social behaviour. Rebelling against established musical trends and social mores, punk quickly became a tradition in itself-- a movement with highly predictable stylistic elements. By 1981, just six years after the formation of the Sex Pistols, a new generation of performers had already begun to assert an identity distinct from the established punk style...Here we come full circle in the evolution of rock-and-roll as seen through the lens of punk. Emerging as the antithesis of the conservative musical climate of the 1970s, punk was quickly absorbed and exploited by the very elements against which it rebelled. Undoubtedly a new generation of performers will soon find an aesthetic and philosophical means of rebelling against the now commercial state of rock, just as punks did in [the 1970s]. (Henry 1989:115,116)

Henry, like so many other commentators, repeats serious errors in subcultural studies: (1) she conflates well-known musicians with the subcultures that listen to them; (2) rather than engage punk on its own terms she reduces punk to a type of youth subculture and little more; (3) she assumes that the ‘cyclical nature of rock-and-roll’ will continue to cycle, without considering the cultural effects of its repeated rotations. Many witnesses fail to see the dialectical motion of the discourse of subculture.

Indeed, commodification and trivialization of subcultural style is becoming ever more rapid and, at the turn of the millenium, subcultures are losing certain powers of speech. Part of what has become the hegemonic discourse of subculture is a misrepresentative depolitization of subcultures; the notion that subcultures were and are little more than hairstyles, quaint slang, and pop songs. In the prism of nostalgia, the politics and ideologies of subcultures are often stripped from them.

For today’s subcultural practitioners what does it mean when subcultures of the previous decades are encapsulated in commercials and nostalgia? Punks, mods, hippies, break dancers, 1970s stoners: all seem relegated to cages in the zoo of history, viewed and laughed at from the smug security of a television monitor. (The sign says, ‘Please do not taunt the historical subcultures’, but who listens?) Today’s subcultural denizens are forced to recognize that yesterday’s subcultures can quite easily be repackaged, made spokeswomen for the new Volkswagen.

One danger industrial pop culture poses to subsequent generations of dissident youth subcultures is that these youths may mistake style as the totality of prior dissent. Commercial culture deprives subcultures of a voice when it succeeds in linking subcultural style to its own products, when it nostalgizes and trivializes historic subcultures, and when it reduces a subculture to just another consumer preference. People within subcultures, for their part, capitulate when they equate commodified style with cooptation, when they believe that grunge, or punk, or break-dancing, is just another way of choosing Pepsi over Coke, when they believe that the entirety of subculture is shallow or stolen.

Dissident youth subculture is normal and expected, even unwittingly hegemonic. Where long hair and denim once threatened the mainstream, it has become mainstream and so has the very idea of subculture. Not only are deviant styles normalized, but subcultural presence is now taken for granted: the fact of subcultures is accepted and anticipated. Subcultures may even serve a useful function for capitalism, by making stylistic innovations that can then become vehicles for new sales. Subcultures became, by the 1970s, if not earlier, a part of everyday life, another category of people in the goings-on of society-- part of the landscape, part of daily life, part of hegemonic normality.

But this fact did not go unnoticed by many in the subcultural world.

Part IV. Long Live Punk: New Ways of Being Subcultural

Looking back at the 1980s one has to ask whether punk really died at all. Perhaps the death of punk symbolically transpired with the elections of Margaret Thatcher in England (1979) and Ronald Reagan in American (1980). The Sex Pistols broke up (1978), Sid Vicious died (1979), and--most damningly--too many teeny-boppers were affecting a safe, suburban version of ‘punk’. For many people, spiked hair and dog collars had become a joke, the domain of soda pop ads and television dramas. But did punk disappear with the utter sell-out of its foremost corporate spokesband, the Sex Pistols? Did punk vanish when pink mohawks could be found only on pubescent heads at the shopping mall? If the spectacular collapse of punk was also the collapse of spectacular subcultures, what remained after the inferno? What crawled from the wreckage? In what ways can young people express their unease with the modern structure of feeling? A new kind of punk has been answering these questions.

After shedding its dog collars and Union Jacks, punk came to be: (1) an anti-modern articulation, and (2) a way of being subcultural while addressing the discursive problems of subcultures. In fact, these two courses prove to be one path. That is, the problems of contemporary punk subcultures, after the ‘death’ of classical subcultures, prove to be intimate with the characteristics of recent modernity. Punk, then, is a position from which to articulate an ideological position without accruing the film of mainstream attention.Contemporary punk subcultures, may therefore choose to avoid spectacle-based interaction with dominant culture. Gone too is the dream of toppling the status quo in subcultural revolution. The culture industry not only proved louder than any subcultural challenge, it was a skilled predator on the prowl for fresh young subcultures. The power to directly confront dominant society was lost also with the increasing speed with which the commodification of deviant styles is achieved. It may be only a matter of months between stylistic innovation and its autonomous language of outsiderness, and its re-presentation in commercials and shopping malls.

Even the un-style of 1990s grunge (an old pair of jeans and a flannel shirt) was converted to the religion of the consumer; baptized and born-again as celebrations of corporate-capitalism. With such history in mind, new social movements such as punk attempt to forego style, shared music, and even names for themselves, for fear of being coopted by the market democracy. Tom Frank, speaking at a convention of zinesters addressed precisely this aspect of the structure of feeling in the 1990s:

The real thing to do is get some content. If you don’t want to be coopted, if you don’t want to be ripped off, there’s only one thing that’s ever going to prevent it and that’s politics. National politics, politics of the workplace, but most importantly politics of culture. Which means getting a clue about what the Culture Trust does and why, and saying what needs to be said about it. As culture is becoming the central pillar of our national economy, the politics of culture are becoming ever more central to the way our lives are played out. Realize that what the Culture Trust is doing is the greatest obscenity, the most arrogant reworking of people’s lives to come down the pike in a hundred years. Be clear from the start: what we’re doing isn’t a subculture; it’s an adversarial culture. (Frank 1996)

To a certain extent, punk means post-punk-- a nameless, covert subculture reformed after punk. To recap: early punk was, in part, simulated ‘anarchy;’ the performance of an unruly mob. So long as it could convince or alarm straight people, it achieved the enactment. For its play to work, punk needed a perplexed and frightened ‘mainstream’ off which to bounce. But when the mainstream proved that it needed punk, punk’s equation was reversed: its negativity became positively commercial. As mainstream style diversified, and as deviant styles were normalized, punk had less to act against. Punk had gambled all its chips on public outcry, and when it could no longer captivate an audience, it was wiped clean. Post-punk, or contemporary punk, has foregone these performances of anarchy and is now almost synonymous with the practice of anarchism.

Long after the ‘death’ of classical punk, post-punk and/or punk subcultures coalesce around praxis. For contemporary punks subcultural memberships, authenticity, and prestige are transacted through action internal to the subculture.

Greil Marcus’ idea of punk’s greatness is that the Sex Pistols could tell Bill Grundy to ‘fuck off’ on television. The real greatness of punk is that it can develop an entire subculture that would tell Bill Grundy and safe, boring television culture as a whole to fuck off directly, establishing a parallel social reality to that of boring consumerism (Van Dorston 1990)

Stripped nude, ideologies developed in the early years of punk continue to provide frameworks for meaningful subculture. Against the threatening purview of mass media and its capacity to usurp and commodify style, punk subcultures steer away from symbolic encounters with the System and create a basis in experience.

Punks, in my work among the anarchist-punks of Seattle, don’t call themselves punks. Instead they obliquely refer to the scene in which they ‘hang out’. They deny that they have rules, and claim that they are socially and ideologically porous. After three decades, here is what has become of many of the CCCS’ spectacular subcultures. And yet, in their stead, vibrant, living subcultures remain, with sets of regulations, norms, and their own ideological turfs. Seattle’s anarchist punks, for example, disavow an orthodox name, costume, or music; yet in many ways they continue to leave, or perhaps squat, within the classical structure of subculture. Although today’s punks refuse to pay the spectacular rent, they find that a new breed of subculture offers them ideological shelter and warmth.

From whence did these latter-day punks come? In contemporary America, the relentless commodification of subcultures has brought about a crisis in the act of subcultural signification. Punk is today, in part, a careful articulation in response to the hyper-inflationary market for subcultural codes and meanings, an evasion of subcultural commodification, and a protest against prefabricated culture; and punk is a subculture that resists the hegemonic discourse of subculture. The public cooptation of punk has led some punks to disclaim early punk, while preserving its more political features. Having been forced, as it were, out of a costume and music-based clique, punk is evolving into one of the most powerful political forces in North America and Europe, making its presence felt in the Battle of Seattle (1999), Quebec City (2001), EarthFirst!, Reclaim the Streets, and in variety of anti-corporate movements.

Like the spectacular subcultures so aptly described by the CCCS in the 1970s, current punks are partly in pursuit of an authentic existence. However, now that stylistic authenticity has been problematized by the ‘conquest of cool’ (Frank 1997a), punks have found that the ultimate authenticity lies in political action. Where subcultures were once a steady source of freshly marketable styles for corporations, they now present corporations with a formidable opponent. Punk marks a terrain in which people steadfastly challenge urban sprawl, war, vivisection, deforestation racism, the exploitation of the Third World, and many other manifestations of corporate-capitalism. The threatening pose has been replaced with the actual threat.

Perhaps that is one of the great secrets of subcultural history: punk faked its own death. Gone was the hair, gone was the boutique clothing, gone was negative rebellion (whatever they do, we’ll do the opposite). Gone was the name. Maybe it had to die, so as to collect its own life insurance. When punk was pronounced dead it bequeathed to its successors--itself-- a new subcultural discourse. The do-it-yourself culture had spawned independent record labels, speciality record stores, and music venues: in these places culture could be produced with less capitalism, more autonomy, and more anonymity. Punk faked its own death so well that everyone believed it. Many people who were still, in essence, punk did not know that they were inhabiting kinds of punk subjectivity. Even today, many people engaged in what might be called punk think of punk only in terms of its classical archetype. Punk can be hidden even to itself.

Punk had to die so that it could live. By slipping free of its orthodoxies-- its costumes, musical regulations, behaviours, and thoughts-- punk embodied the anarchism it aspired to. Decentralized, anti-hierarchical, mobile, and invisible, punk has become a loose assemblage of guerilla militias. It cannot be owned; it cannot be sold. It upholds the principles of anarchism, yet has no ideology. It is called punk, yet it has no name.

#Punk#Subculture#Post-subculture#Dylan Clark#Punk is Dead#Long live punk#David Muggleton#Hebdige#Politics#Theory

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

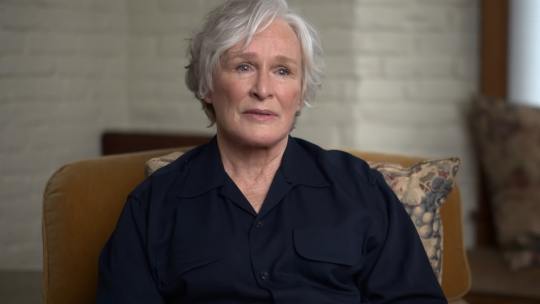

Glenn Close Suffered Physical and Emotional 'Devastation' Growing Up in a 'Cult'

Glenn Close Suffered Physical and Emotional ‘Devastation’ Growing Up in a ‘Cult’

Glenn Close opened up about her time growing up as a member of the Moral Re-Armament movement, or MRA, which she described as “basically a cult.”

The legendary actress was just one of the people featured in Oprah Winfrey and Prince Harry’s new mental health docuseries “The Me You Can’t See,” sharing how her childhood affected her and her family in the long run.

Close’s family joined MRA when…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Glenn Close Suffered Physical And Emotional 'Devastation' Growing Up In A 'Cult'

Glenn Close Suffered Physical And Emotional ‘Devastation’ Growing Up In A ‘Cult’

Glenn Close opened up about her time growing up as a member of the Moral Re-Armament movement, or MRA, which she described as “basically a cult.”

The legendary actress was just one of the people featured in Oprah Winfrey and Prince Harry’s new mental health docuseries “The Me You Can’t See,” sharing how her childhood affected her and her family in the long run.

Close’s family joined MRA when…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Glenn Close: You lose power if you get angry

From vengeful mistress to Agatha Christie matriarch: the actor talks about Harvey Weinstein, mental illness and growing up in a cult

Glenn Close and I sit at the corner of a large boardroom table in an intimidatingly minimalist office on the 14th floor of a Los Angeles talent agency. Its the kind of environment in which Patty Hewes, the ruthless lawyer Close played in Damages for five seasons, would feel at home and Im almost waiting for her to stand up, slam both hands on the table and shout, Ill rip your face off or any of the other terrifying put-downs that defined her double Emmy award-winning performance.

But Close is in high spirits and radiates such warmth I barely notice the chill from the tower blocks air-con. After we fiddle with the settings on our swivel chairs, which are so high they make anyone under six foot kick their legs like a child on a swing, the 70-year-old, six-time Oscar nominee and star of stage, television and film starts telling me about her dreams. I have had a lot recently, full of this wonderful love for a younger man. The dreams just keep coming and I wake up thinking, that was wonderful! It wasnt necessarily us doing the sexual act, just the feeling of love.

With her white hair cut to a sharp crop, and wearing a relaxed navy blazer, chinos and black scarf on account of the arctic corporate temperature, she looks stylish and fit. I have never felt better in my life, and I am, like, 70, she says. Im really a late bloomer.

She says she feels a disconnect between how she sees herself and how people may view me when I walk down the street, like: Theres an old lady. You know, there is now this cult of the model. Everyone on the red carpet is made into a model. That is very hard to not play into I have a bit of podge I am trying to get rid of, but its hard. I just think, Oh fuck, Ive been doing this my whole life! But the irony is, you just get better and better with age. You dont feel less alive or less sexy.

In Agatha Christies Crooked House. Photograph: Nick Wall

We are here to talk about Crooked House, the Agatha Christie adaptation debuting on Channel 5, before its theatrical release, in which Close plays Lady Edith, a matriarch of a very dysfunctional family. Close says, Christies grandson came to the set and he validated the fact that it was her favourite book, and the one that had never been adapted. He said when she handed it to the publisher, she was told she had to change the ending, because it was too upsetting and controversial. She refused. Its still pretty controversial.

This production, co-written by Julian Fellowes, might not be as spendy as Kenneth Branaghs $55m Murder On The Orient Express, but the ensemble cast is equally starry: joining Close are Gillian Anderson, Max Irons, Terence Stamp and Christina Hendricks. Close presides over her co-stars with gravitas and grace, in an understated performance that finds the humour in an otherwise bleak setup. But youd expect nothing less from the actor whose 40 years in the business started with star turns in Broadway productions (she won a Best Actress Tony in 1983 for Tom Stoppards The Real Thing). Her first film role, at the age of 35, was with Robin Williams in The World According To Garp, for which she received an Oscar nomination as she did for her supporting roles in The Big Chill and The Natural. Her performances in Fatal Attraction, Dangerous Liaisons and Albert Nobbs, about the life of a transgender butler in late 19th century Ireland, which she also co-wrote, racked up further Oscar nominations but still no win. This is seen by many as a travesty: Close brings a precision to her film work, honed through her years on stage. She has that rare taut quality Jack Nicholson also has it where you believe that beneath the steely control she is capable of snapping at any moment.

It was this that led Andrew Lloyd Webber to cast her in 1993 as the tragic silent movie star Norma Desmond in Sunset Boulevard on Broadway. Close reprised the role 23 years later, getting her old costumes out of storage (she has kept all her costumes and recently donated the collection to a university in Indiana) for its revival in Londons West End.

As Alex Forrest in Fatal Attraction: Clearly she had mental health issues. Photograph: Rex/Shutterstock

But it was her Oscar-nominated turn as Alex Forrest in Fatal Attraction in 1987 that proved career-defining. Thirty years on, Close still counts Forrest as the character of whom she feels most fond; she has admitted to fighting tooth and nail against the films eventual denouement, which turned the character into a bunny-boiling psychopath and Close into the casting directors go-to woman on the verge for years afterwards. Now we have the vocabulary to talk about these things, clearly she had mental health issues, she says.

Close sits regally still as she speaks, emphasising her points by leaning forward and locking eyes. Shes comfortable with silences and often takes a theatrical beat or two before answering questions. Shes all poise and control, but does she ever lose her temper?

I express my feelings quietly. I am not afraid of confrontation, but I am not particularly good at it. If I get attacked, I am not good at attacking back. There is fight, flight and freeze and I tend to freeze. That is not a strength of mine. I love the fact that my daughter Annie [Starke, an actor] is more of a fighter than I am. She doesnt let people get away with shit. While she agrees that women have a harder time being angry, publicly, than men, she says, I have played a lot of characters, and actually anger makes you lose power. Patty Hewes [in Damages] she hardly ever lost her temper, but when she did, it was very specific. I have always felt you lose power if you get that angry.

The collective outpouring of anger among women in Hollywood right now is something of which Close is acutely aware. She says that sexism in the industry has shifted more slowly than it should have done throughout her career: It took Harvey Weinstein and someone calling him out [for real change to happen]. I know Harvey, and he has never done that to me, but people would say he was a pig. I never knew that it was that bad and I dont personally know anybody who has endured that. I would like to think that I would have done something about it.

We discuss whether its possible to separate the work from the personalities involved in it. News has just broken that House Of Cards will be back for another series without Kevin Spacey, after it was originally canned because of harassment claims brought against its leading man. Close wraps her scarf around her chest and fixes me with her electric eyes. Artists, to make a huge generality, walk on a very thin line. Sometimes, like my beloved friend Robin Williams, who was one step away from madness, whatever makes them a great artist also makes them very complicated human beings. Again, that doesnt mean they can prey on and abuse people.

With Harvey Weinstein in 2013. Photograph: Mike Coppola/Getty Images

At the root of the problem of sexism in Hollywood right now is, Close says, biology. I think the way men have treated women, from the beginning of time, is because they have different brains to women. So I am not surprised by it at all. I say to a guy, Tell me the truth, if you see a woman walk into a room, what is the first thought that goes through your head? His answer, always, is, Would I fuck her? It doesnt mean they act on it. If you can evolve into a society where men know that they should not always act on it then there has been a positive revolution. But you cant just say that theyre not going to have the thought that is ridiculous. It also has to be the women, who are not powerful, to be OK to say no and leave the room. I think its unrealistic to say were going to change but we have to evolve.

I ask Close who she thinks is a great man today. She is silent, thinking, for what feels like a full 60 seconds in which I am so tempted to throw out some options: Barack Obama, the Pope, the friendly security guard on reception who let us in

Nelson Mandela, is her final answer, but Im not sure shes convinced. I guess for me, she says, greatness is taking your humanity and still doing the good thing. Its sad to say that there are very few men, who are leaders, who have some sort of moral code that they dont deviate from because of popular opinion.

She thinks we are undergoing a crisis of masculinity: In the public mind, yes. I was outraged when I heard that there was a war against men I was like, are you joking? What do you think has been happening against women for centuries?

Close knows all too well about the misuse of power, because her own upbringing was, as she puts it, complicated. When she was seven, her parents joined a cult. Moral Re-Armament or MRA was a modern, nondenominational movement founded by an American evangelical fundamentalist which extolled the four absolutes: honesty, purity, unselfishness and love. Her father, a physician working in the Congo, sent Close with her brother and two sisters from the family home in Greenwich, Connecticut, to live at the MRA HQ in Caux, Switzerland (Closes mother, Bettine, was a socialite).

She is vague on the details but clear on the impact this experience had on her as a teenager: I was repressed, clueless and guilt-ridden. The timeline is patchy, but Close travelled with MRA in the 60s as a member of their musical groups, and spent time back in Connecticut at an elite boarding school. I had a wonderful time at Rosemary Hall, a girls school, she says. I was in a renegade singing group called the Fingernails: A Group With Polish. But she remained, as she calls it clueless. A lot of my friends knew boys youd have these horrendous dances with boys schools and they would get the guys they wanted and I would just stay with the person I was with.

As Patty Hewes in Damages. Photograph: Rex/Shutterstock

She was briefly married before going to university. It is a complicated story for me. I was married before college, and kind of in an arranged marriage when you look back on it, and my marriage broke up when I went to college, as it should have. I was 22. But my liberal arts school had a wonderful theatre that was my training, my acting school.

Was that where she finally learned about sex, popular culture, the ways of the world? Not really, she says. I still am learning.

Close has two sisters, Tina the eldest, and Jessie her younger sister; and two brothers, Alexander, and Tambu Misoki, who was adopted by Closes parents while living in Africa. At the age of 50, Jessie spent time in a psychiatric hospital and was diagnosed with bipolar disorder, a weight that had been hanging over the family, undiscussed, for years. Talking about mental illness just wasnt done, Close says. You dont have a vocabulary for it and youre also very aware of appearances. You dont want to appear a crazy family.

In 2010 Close founded Bring Change to Mind, a charity that aims to end the stigma around mental illness by talking openly about it and its effect on families. It was my nephew who was first diagnosed with schizoaffective disorder. This is basically schizophrenia with an ingredient of bipolar. And when that happened, it was like, What? My sister Jessie, his mother, didnt know what was wrong. He went to the hospital for two years and that saved his life. Then Jessie was, finally, correctly diagnosed herself.

With sister Jessie in 2009. Photograph: Getty Images

Close felt a duty to her family to give them a high-profile person who is not afraid to talk about it publicly. It affects the whole family. We always knew my grandmother and mother had depression my sister does, I do to a certain extent. But I didnt know my great-uncle had schizophrenia. I knew my half-uncle died by suicide. There was a lot of alcoholism addiction, self-medication. Nobody ever talked about it. I knew my grandmother was depressed, but at first I thought she lived in a hotel, not a hospital, because she always said how good the food was.

Close says she and her siblings are of one mind politically, but admits she does have members of her family who voted for Trump. I tried to understand that. Theyre not crazy people who have been brainwashed by Fox News, but I try to understand the anger, because I think that has been building up ever since Watergate. It was watching that scandal unfold that made her realise Americans have always been naive, we just take for granted what we have, and we always thought of our leaders as good people. With Watergate, people became cynical about government.

Today, she says, Washington is a bunch of self-serving She searches for an expletive and after a second settles on men. She says, Its hard to believe that people are so out for themselves. It goes against what you would like to believe about your country. I feel eloquence is incredibly important for a leader, and we had that with Barack Obama, who made his initial impact because he gave that incredibly eloquent speech, but he lost his eloquence in his presidency. We always need someone to say, I hear you, someone who can put their words into unity and hope and we dont have that. I think the last person may have been Robert Kennedy.

And now you have Trump tweeting nonsense.

Its devastating. Social networks are now like our nervous system, and if you keep pumping that kind of crap into the nervous system, it is going to have an effect on a population.

With Kevin Kline in The Big Chill. Photograph: Rex/Shutterstock

Close doesnt talk politics with her friends because she doesnt really have many friends. I have always forced myself into situations I am not comfortable in. I am an introvert, and I was painfully shy as a child. I think I still have a big dollop of that in my persona. I read a book called Quiet: The Power Of Introverts In A World That Cant Stop Talking and it was a real comfort to me I realised I was that person I had always been. And it was at that point I told myself to stop pushing myself into situations that I dont enjoy. I dread cocktail parties.

She tells me shes pretty reclusive and can count her closest friends on two fingers. I ask if shes still good friends with Meryl Streep.

I have never been close friends with Meryl. We have huge respect for each other, but I have only done one thing with her, The House Of The Spirits.

I apologise for assuming they were pals, being of a similar age and stature in Hollywood, and admit this negates my next question: Who would win in an arm wrestle, you or Meryl?

Close laughs. Oh, I would, because I am very strong.

***

The tightest bond Close has is with her only daughter Annie, 29. Annies father is the film producer John Starke whom Close dated for four years from 1987, but never married. Annie was never a door-slamming, difficult teenager. Close tells me: When my Annie was three, she looked at me, and said, I want you. I knew what she meant. I, at the time, was a single working parent, sometimes even when I was home, working or producing something, I was there and not there.

With daughter Annie Starke in 2010. Photograph: Rex/Shutterstock

She doesnt think its any easier for working mothers today and acknowledges, I had it easy because I could afford to have help think of the women who cant afford it and have to put their child in some shaky childcare centre. No, I think it is incredibly hard for women. Any person, in any profession, feels that tug [of guilt]. We discuss the intimacy of the single-parent, only-child bond. Once, I went to vacuum Annies car seat as we were moving house, and a lot of life had happened there, so I was crying. She said, Mummy, are you OK? I said, Yeah, Im OK. And she said, Here I am.

She was married to businessman James Marlas from 1984 to 1987 and then, following other relationships, including that with Starke, she married again, in 2006, to venture capitalist David Evans Shaw, divorcing him nine years later.

Would she marry again?

I dont know.

Does she think marriage is important?

I think it is a positive evolutionary component that we are better with a partner. I think to have a partner that you can go through life with, creating a history with, that you can find a comfort with, have children with there is nothing better. This is an opinion I have come to very late in life, at an ironic moment, where I dont have any of that. I dont know if I will again. But I do think its a basic human need to be connected.

Despite this, shes happy on her own right now. This is a good time in life. I do think, what would it be like to have a partner again? But it would have to be very different from what I had before. Then I have that great dream and wake up happy.

Crooked House is on Channel 5 at 9pm on 17 December.

Commenting on this piece? If you would like your comment to be considered for inclusion on Weekend magazines letters page in print, please email [email protected], including your name and address (not for publication).

Read more: https://www.theguardian.com/film/2017/dec/16/glenn-close-harvey-weinstein-mental-illness-cult-fatal-attraction

from Viral News HQ http://ift.tt/2npFUB4

via Viral News HQ

0 notes

Text

Kwame Nkrumah on the methods of neo-colonialism (from Neo-Colonialism, the Last Stage of Imperialism):

Some of these methods used by neo-colonialists to slip past our guard must now be examined. The first is retention by the departing colonialists of various kinds of privileges which infringe on our sovereignty: that of setting up military bases or stationing troops in former colonies and the supplying of ‘advisers’ of one sort or another. Sometimes a number of ‘rights’ are demanded: land concessions, prospecting rights for minerals and/or oil; the ‘right’ to collect customs, to carry out administration, to issue paper money; to be exempt from customs duties and/or taxes for expatriate enterprises; and, above all, the ‘right’ to provide ‘aid’. Also demanded and granted are privileges in the cultural field; that Western information services be exclusive; and that those from socialist countries be excluded.

Even the cinema stories of fabulous Hollywood are loaded. One has only to listen to the cheers of an African audience as Hollywood’s heroes slaughter red Indians or Asiatics to understand the effectiveness of this weapon. For, in the developing continents, where the colonialist heritage has left a vast majority still illiterate, even the smallest child gets the message contained in the blood and thunder stories emanating from California. And along with murder and the Wild West goes an incessant barrage of anti-socialist propaganda, in which the trade union man, the revolutionary, or the man of dark skin is generally cast as the villain, while the policeman, the gum-shoe, the Federal agent — in a word, the CIA — type spy is ever the hero. Here, truly, is the ideological under-belly of those political murders which so often use local people as their instruments.