#mount rainier camp muir weather

Text

“If you don’t like the weather, wait 5 minutes.”

Truer words may never have been spoken about springtime in the Cascade Mountains.

The only thing you can really count on with our weather is that the weather will change. We can go from blue sky to white-out in 5 minutes. It might get worse, it might get better, but the weather on this mountain is always interesting.

So before you drive out to visit the national park, please check the weather forecast and prepare for the possibilities. When you get to the park, you might check again at the visitor center or information center. Then, while you’re out having fun, watch the weather. If it starts to change, be prepared to adjust your plans.

In the Spring, I have counted 136 different kinds of weather inside of 24 hours. – Mark Twain

Park information on weather can be found here https://www.nps.gov/mora/planyourvisit/weather.htm For a view of current conditions, these webcams may be helpful https://www.nps.gov/mora/learn/photosmultimedia/webcams.htm Park information on winter safety can be found here https://www.nps.gov/mora/planyourvisit/winter-safety.htm

These photos are from years past and do not reflect current conditions. NPS Photo. Mount Rainier with high clouds viewed from Longmire. Snowbank in foreground. March 2021. NPS/S. Redman Photo. Clouds around Tatoosh Mountains with snow. Silhouette of evergreens and two ravens on a dead tree in the foreground. December 2010. NPS Photo. View looking up the Carbon Glacier. Clouds obscure most of the mountain with Liberty Cap (14,122 feet) visible above. July 2004. NPS Photo. View looking down on buildings of Camp Muir and Muir Snowfield. Light dusting of snow. Clouds obscure features below. June 1968.

28 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Mt. Rainier

Paradise to Camp Muir: 4,788 ft gain in 5:49

Camp Muir to Summit: 4,222 ft gain in 5:50

Final elevation: 14,410 ft

Link: https://www.alltrails.com/trail/us/washington/mount-rainier-standard-summit-route

Buckle up for this one because it’s going to be a long one.

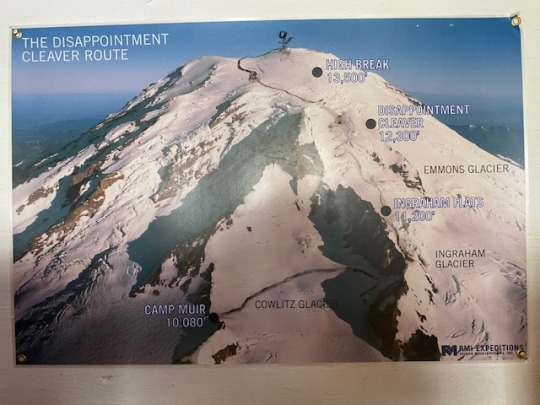

I was supposed to climb Mt. Rainier last year, but the trip got canceled because of COVID. I knew this was going to be one of my toughest highpoints to check off, and I wanted to use it as an opportunity to learn as much as possible to learn about alpine and glacier traveling. RMI Expeditions offered a 5-day program with multiple days of training, so I knew it was the perfect route for me to go.

I got picked up in Seattle by some other people on the trip, and we made our way to basecamp in Ashford. The first day was just orientation and gear check. I had to rent a few pieces of equipment, but most of the stuff on the list I either had already or was able to borrow from Nick back in Salt Lake. Some interesting gear that I didn’t have any prior experience with were crampons, double leather boots, gaiters, and an ice axe.

We also met our lead guide, Jenny, on the first day. All I can say about Jenny is that she’s a total badass, and I knew that she was going to get us up and down that mountain safely. Our team had 8 climbers not including the guides: Chris, Minia, Jim, Jason, Jamie, Ricky, Eli, and myself.

Once we had all our gear sorted out and learned the best way to stuff it all into a backpack, we broke for the day. I was staying at a campsite only a few miles away, so I headed there to try and rest up for the big days to come. Conveniently, this campsite featured a bird that constantly pecked at the metal roof of the building in the center of the camp as well as a small army of screaming children with their parents’ Trump flags billowing in the wind. Terrific stuff.

Day 2 was a training day. We went to a snowy part near the bottom of the mountain and learned how to walk up and down hills with crampons, self and team arrest with an ice axe, anchor an ice spike, and walk as a team of 4 people. On Rainier, we’d be tethered together for nearly the whole climb. There needs to be 30 ft of rope between each person because that’s how wide the crevasses are on the mountain in case someone falls in. Jamie also shared that she had fallen into a crevasse while trying to climb Mt. Baker, so the dangers of the climb were starting to become more and more apparent.

We also got to meet our second guide, Steve, who used to be a pro hockey player and is missing his two front teeth to prove it. He actually plays now for the Idaho team in the BDHL, which I’m trying to play for in Park City. Small world!

After minimal training I still felt incredibly unprepared, but that didn’t matter because we were climbing anyways. The next day, we met a Paradise parking lot at around 9 am and started our climb! Our goal for that day was to get to Camp Muir, where we’d be staying for our nights on the mountain. It has a bunkhouse for us to sleep in as well as tents for the unvaxxed folks.

The hike up to Camp Muir was a slog and gave us a taste of exactly how difficult this climb would be. Steep hills and slushy snow made for some tough terrain, but it was nothing we couldn’t handle. We all walked in a straight line, with each person kick-stepping into the previous person’s footprints. This meant the last person in line had practically a staircase for all the steep hills. Imagine climbing a 5,000 ft high staircase with a 40 lb backpack on your back, and that’s roughly what our experience was like. Chris ended up falling way behind and Eli pulled something in his leg about 75% of the way up, and it was tough to see team members fall off like that.

I think the worst part was that everything seemed deceptively close. When we caught out first glimpse of Camp Muir, it looked like it was 5 minutes away. Wrong! We still had another hour to go after seeing it. That bit was demoralizing.

Eventually we all made it to Camp Muir and claimed our spots in the bunkhouse. The guides provided hot water for our meals and prepared us for the next day. Based on the weather forecast, our best chance to summit would be the next day. This means waking up at 12:30 am and heading out of camp at 2 am, so we all headed to bed straight after dinner. The elevation and general excitement/anxiety led me to get MAYBE an hour of sleep before the guides came roaring in at 12:30 to wake us up. They said it was pretty normal to not sleep the night before the climb, but that didn’t make me feel any less tired.

Chris and Eli weren’t fit to climb, so we departed as a team of 6 with our guides. With only our headlamps to guide us, all you could really do was keep your head down and look at your feet. We had to conserve energy by rest-stepping into the footprints of the person in front of you. I started out on a rope with Jenny and Minia, and Jenny set us off into the darkness with a nice, slow pace.

We crossed Cowlitz Glacier and then made it to Ingraham Glacier. The scariest part was crossing some pretty narrow bridges over crevasses. I tried not to think about the fact that you couldn’t see the bottom when you looked down them and just focused on putting one foot in front of the other. After crossing the glaciers, we took our first break after about an hour. We put our parkas on to stay warm and tried our best to force food and water down. It’s crazy how hard it is to eat at that elevation. This was also where Minia decided she couldn’t go any further, so one of the guides took her back and we changed up our rope teams. Now we’re down to 5 members.

The next bit was absolutely debilitating. We had to ascend Disappointment Cleaver (cleaver? I barely know her), which was a rocky section full of switchbacks. Normally I feel pretty at-home while scrambling over rocks, but doing it in crampons with full backpacks and no light was terrible. All I tried to do was focus on my breathing and ignore the grating sounds of metal spikes on rocks. I was tied in with Ricky for this part, and I could tell he was having a hard time. After about an hour and half of climbing, we sat down for our second break and had a breathtaking view of the sunrise. That view alone almost made the cleaver worth it, but I can barely put into words how much that part sucked.

Break passed quickly, and before we could start up again Jim decided that he couldn’t go any further. Jenny made the executive decision to call it for Ricky too, so they both tied up with another guide and started heading back down. Now there were only 3 of our original team left: Jason, Jamie, and myself. We all tied in with Jenny and became the J-Line (since, ya know, my middle name is John…)

The next bit I could only describe as a seemingly never-ending staircase. At this elevation, every step becomes a struggle. Our pace is slow but steady, I’d say we’re taking roughly one step every two seconds. Try that out for a quick second to understand just how slow our pace needed to be to be sustainable.

The last leg really took its toll on Jamie who was in the back. I was trying to crack jokes to keep team morale high, but everyone was getting their ass kicked by this crazy mountain. After what felt like an eternity of climbing, we eventually reach the crater at the top of the mountain. The crater is considered the summit, but the true summit was about another 30 minute hike past this point. I was so excited and full of adrenaline that I practically ran toward it. Jamie and Jason stayed behind, content with the crater, so I ended up being the only person of my 8 person team to reach the true summit.

I snapped some pictures up there (and recorded a quick clip for my next Survivor application) before starting to feel light-headed and heading back to the team on the crater. Little did I know that my rushing to the true summit would lead to a truly miserable descent: my trip to the top meant that I didn’t get a break like the rest of the team. As soon as I made it back to the crater, I had about 2 minutes of sitting before it was time to head down. We were in a time crunch because some unusual heat was going to produce bad descent conditions, so we needed to leave before it got too bad. I thought I’d be ok with a super short break, but boy was I wrong.

The heat, the elevation, and the exhaustion proceeded to destroy my body on the descent. My head hurt, my body ached, and I started to get tunnel vision. I had to keep telling myself “the only way off this mountain is down, and you sure as hell can’t afford a copter ride out of here.” I was stumbling all over the place and started getting really scared that things were going to end badly.

Pure grit got me to the first break, where I felt nauseous and could barely eat or drink. I put away as much water as I could, which made me feel only slighter better. Still, the only way off was down, and it was time for Disappointment Cleaver round two.

Downhill rocks with crampons on felt like a living nightmare. I was slipping a ton and I was walking in a daze. It felt like a miracle when we finally made it through and returned to the snow. This came with its own frustrations, as Jason and I kept post-holing waist deep into the snow. I wanted to shout and cry and just lay down every time this happened. My morale never felt lower.

I think one of my favorite things about hiking is just the simplicity of it. All you do is put left foot over right foot over left foot until you make it to your destination. The best I could do was focus on this as we continued our descent to Camp Muir. When we finally rounded the corner and saw it, I nearly wept. I felt terrible: I was out of water, my head was throbbing, my clothes were soaked from sweat, and my feet felt like they were about to fall off. The final steps into camp had me on the brink of collapsing.

I immediately rushed into the bunkhouse to take off my layers and try to hydrate and cool down. I laid in my bunk for a couple hours but didn’t feel any better. I was guzzling water but wasn’t peeing, which had me worried. I felt nauseous and dizzy and couldn’t cool down. Jenny came to check on me, and said that I probably had heat exhaustion, which is crazy to think of when you’re on a mountain covered in snow. She said that all the water I drank was diluting my body, and that my body was probably starved of electrolytes. She made me a quesadilla and brought me a Gatorade as I continued laying in bed.

After trying unsuccessfully to sleep it off, I went outside and proceeded to immediately throw up everything. The liter and a half of water I had drank since we got back came spewing out. The good thing is that this helped with my nausea! I still felt like ass, though. I went back into the bunkhouse and tried to sip the Gatorade and nibble the quesadilla as much as my body would allow me. Luckily, I was able to get a bit of a nap in too. I had gone the last 30 or so hours on only an hour of sleep, and my body was not happy about it.

The nap + Gatorade + quesadilla combo helped me to feel a lot better. It still felt like a struggle to get anything into my body. The rest of the team met with the guides to learn some knots since we had time to kill, but I didn’t have any strength to get out of bed. That was a low moment for me.

Night finally fell and it felt like a miracle that I was able to get some sleep. The wind was howling all night and there was a symphony of snoring coming from the other bunks. I woke up around 4 am and actually felt moderately ok, so I think my body was finally recovering.

I kept sleeping on and off until it got to be about time to go. We packed everything up and it was finally time to get the hell off this mountain. The Camp Muir to Paradise hike was almost enjoyable even. It was all downhill so we kept a good pace, and there were tons of “luge” spots where you could slide down on your ass. That’s my kind of descent.

After about 2 hours, we finally made it to the pavement of the Paradise parking lot, and I wanted to kiss the ground. We headed back to Ashford to return our rental gear and celebrate with our team over some beer and burgers.

Man, what an incredible experience this trip was! I loved how much fun our team was and how knowledgeable the guides were. We all kept each other in good spirits, and I got up and down the mountain (mostly) safely. That’s all I could really ask for. All in all, though, I think I’m ok to not do any more hikes for a little while. Only 48 more highpoints to go!

0 notes

Text

8.1 - Climb for Hope

Anna and I flew into Portland on a Wednesday evening. We were scooped up at the airport by a guide with Rare Earth Adventures, the company that graciously donates their time and energy to Climb for Hope. After a quick introduction, she loaded our hefty bags into the back of the van and mused, “I thought you guys were going to be older!” Once we were deposited at the group’s homeshare, her comment started to make a bit more sense. We were greeted by the three other members of the expedition, and all had a decade (or two!) on Anna and me. Darkness was already descending on our suburban Washington backyard-for-rent, and we gathered around the furnished treehouse (a major selling-point on the Air BnB profile) to exchange pleasantries. The air was thick with a tension not inappropriate between strangers about to entrust their lives to one another, and the weight of what we were about to attempt settled in a bit as we shared stories of past adventures. Andy, the trip organizer, had attempted Rainier thrice and summited only once before. The two other climbers had both tried, and failed, to reach the summit, once stuck in a tent for over 30 hours awaiting a lull in the weather that would never come. On that particular trip, winds had blown a ladder into a crevasse, effectively cutting off the summit from an entire side of the mountain. Facing this literally chilling possibility, Anna and I opted against the treehouse, and we settled into one of the upstairs rooms for the night.

After a quick gear check in the morning, we loaded into a van and set out for the mountain. The car ride offered us the first opportunity to really get to know the team with whom we would eat, sleep, suffer, and – hopefully – summit. The trip was organized by Andy Buerger, a climber and entrepreneur out of Baltimore, whom I met - albeit briefly - through connections in the natural food industry. He founded Climb for Hope after losing his sister Jodi to breast cancer, and expanded its mission after his wife and climbing partner was diagnosed with MS. Andy struck me as a man of great emotional depth, though his busy mind seemed to hold this at bay much of the time. He works incredibly hard to keep his symbiotic ventures chugging along, and was even caught sneaking work emails during our downtime at camp. Possessing a wicked deadpan, Andy settled into the role of sarcastic diva for much of the trip, slinging outrageous insults and complaints at guides and climbers alike in a way that clearly said, “I’m genuinely happy we’re all here.” Indeed, that seemed to be a general mantra for Andy, clouded only slightly by his survivor’s guilt, and his aura of gratitude helped remind us all that our suffering – both on the mountain and off it – was merely a window into the daily experiences of those who fight grave illness back home.

Andy’s long standing climbing-partner-in-crime was Danny, a DC policy-worker able to switch breathlessly between discussions of eastern philosophy and the particular qualities of his selfie stick. Self-deprecating, yet charming, sophomoric, yet wise, Danny was effortlessly easy to get along with no matter his mood or fancy. He and Andy had the report of two long-since-graduated fraternity brothers, and were at the root of an ever-expanding ring of scatological pranks that would chase us up and down the mountain. He seemed to be the unofficial marketing guru for Climb for Hope, and he worked doggedly to document the trip. With equal gusto, he pursued both cheesy, Instagram-ready bits of content and one of the great challenges of the adventuring life: capturing the scale and beauty of what we do in the mountains in a way that inspires a love and respect for the natural world.

The third, and oldest member of the expedition was Tiger, a boyishly energetic anglophile who imports small-batch craft cider from the UK. Despite his gentlemanly inclination, he happily adopted the role of “Creepy Uncle Tiger” simply because it was so damn funny. His gasping giggle was so infectious, his stories often left us all in hysterics, even if no one really understood what he had said. Tiger - himself a cancer survivor - was fiercely dedicated to the cause, and carried photographs of friends and family fighting the disease back home. He also carried a well-worn letter from his daughter, which he would discover for the first time described him as the strongest person she knew, not strangest, as he had happily assumed for over five years. As we would discover, Tiger was both strong and strange, as well as perceptive, generous, and absolutely hilarious.

A rare moment on flat ground

For our final night before undertaking the climb, we stayed just outside the gates of the National Park, in a wooden bunkhouse built by loggers in 1912. Out of respect for the altitude and challenges that lay ahead, we resisted the temptation to settle our nerves with a beer, but despite dinner conversation revolving around the possibility of going ten days without a bowel movement, I devoured a mediocre burger without taking a breath. Anna, on the other hand was slipping deeper into the world’s worst-timed cold, and scarcely ate. We were both clearly worried over her worsening condition, but didn’t dare discuss the implications, so she loaded up on Nyquil and we settled down in our 4-person room for one final night on a proper bed.

Rainier National Park is - deservedly - a huge tourist destination. Temperate rainforest covers much of its area, dense with intricate ferns, large-leafed clover, and enormous nurse logs impossible to find in the heavily-logged areas that surround the park. On our drive in, the forest would occasionally drop out from under us, and we would find ourselves on a winding bridge spanning a vast scar in the vegetation, canyons full of grey volcanic talus where the receding glacier had pulverized the landscape ages ago. In most cases, water rushed through the middle of these canyons, carrying glacial melt down to Seattle, the Sound, and the Sea. Rainier remained hidden for much of the approach, but once the titanic thing slipped into our view from behind the surrounding peaks, it was there to stay. As we pulled into Paradise, the trailhead where we would begin our climb, Rainier drew our gaze with an almost supernatural force. The mountain was tall - no doubt about that - but it was also wide, filling your entire field of view and almost seeming to wrap its imposing walls around you in embrace. A few mountaineering teams were already beginning their push, but mostly Paradise was filled with day-use visitors, picnicking, snapping photos, and generally basking in the magnificence of Rainier’s singular presence here. With this din casting an odd irreverence over the moment, the team exchanged some quiet words of encouragement, inspiration, and caution, then began up the trail.

All smiles at the trailhead

Our objective for Day 1 was Camp Muir, and to my great surprise, a trail marker not 100 yards into our hike indicated that it was only 4.1 miles from the Paradise parking lot. It helped to explain the crowded trail, full of day-hikers in shorts, sometimes carrying nothing more than a water bottle. What a sight we must have been to these untroubled families, lumbering sternly upward, already sweating under the weight of packs so full of food, fuel, clothing, and shelter that axes, pickets, crampons, shovels and avalanche probes had to be strapped to the outside. By nine, I began to worry that Anna and I had packed for the entirely wrong season. I was wearing my lightest layers, a long-sleeved cotton tee and fully-taped Gore-Tex pants, and sweating mightily. Still, the weather was undeniably incredible. The slightest breeze rustled through the intertwined noble pines, and sloped meadows of wildflowers glowed under the morning sun. Huge golden marmots loafed on rocks by the side of the trail and lumbered through the fields chomping on the purple blooms of lupine. In their careless company, even the distant peak of Rainier seemed welcoming.

Despite the short distance, the hike stretched on for hours. Paved road gave way to packed dirt, then to rocky switchbacks, and then to slush. At the foot of the Muir Snowfield, Anna and I were already exhausted. The snow was soft enough that crampons were unnecessary, but this made for painfully slow progress under the weight of our equipment. While many day-hikers had turned around at the snowline, some pressed on towards Camp Muir, the highest point on the mountain accessible without a wilderness permit. Their light footfalls and happy chatter was brutally demoralizing as we trudged up the glacier, where the monotonous landscape deceived depth perception and seemed to stretch on endlessly. Even worse were the whoops of delight from climbers on their descent, many of whom glissaded down well-traveled slides on tarps, stuff sacks, or even sleeping bags. Anna in particular eyed the descending parties with envy, as the morning dose of pseudoephedrine was now long gone. At about 9000 feet a few small structures came into view, and we pushed for camp with a renewed vigor. Anna and I fell in step behind Tiger, who demonstrated a technique for “micro-resting,” pausing momentarily every third step to lock the knee in your back leg. I didn’t find much rest this way, but the surprisingly difficult coordination of stepping, counting, and locking gave me something to think about besides the camp that seemed to draw no closer.

At last, we crested the top of the ridge and arrived at Camp Muir. 10,080 feet above sea level, the camp sat at the south end of a large, rippling snowfield, speckled with rockfall and greyed with the volcanic dust that seemed to be everywhere at this height. To the south, from whence we’d hiked, the forest stretched endlessly out towards the horizon. Across the valley three large mountains stood in a neat line: Mount Adams, wide and glaciated, like Rainier’s slightly stunted cousin; Mount Hood, symmetrical and improbably steep, like the mountains a child would draw on an imaginary map; and Mount St. Helens, pointing her jagged crater directly at us, a warning to all who tempt fate in the shadow of Rainier (due to its proximity to Seattle and relatively high levels of geothermic activity, Rainier is considered one of the most dangerous volcanoes in the world). We set about making camp for the night, flattening the snow with our avalanche shovels to make room for our tents, while the guides got to work boiling water.

Our intrepid guides, Brandon, Julie, and Cody

Boiling water (or more specifically, boiling snow to make potable water) was a seemingly endless chore on the mountain. Algae grows everywhere (generally invisibly, though pink “watermelon snow” is a common occurrence), and ingesting it is a sure path to digestive unhappiness. Incredibly, the guides insisted on doing this work themselves, in particular Julie, who continued to surprise us with her ability for selflessness and empathy. Freshly returned from non-profit work in Peru, Julie was an adventurous soul with a calm demeanor and easy smile. As the only other female on the team, she was hugely supportive of Anna throughout, and indeed to us all. She seemed to have a sixth sense for sniffing out a client in need, and was always ready with first aid, toilet paper, a snack, or simply a well-timed story when the crunching of snow underfoot was about to become unbearable. Like the rest of the guides, she had an arsenal of horror stories skillfully spun to paint our climb as a tropical vacation and make us all feel like Navy SEALS in comparison.

The lead guide on the expedition was an unassuming badass named Brandon. As we would learn later, Brandon had left a lucrative career to care for his ailing wife, but he gave no indication of dissatisfaction. In fact, he clearly thrived in the mountains, hiking tirelessly on hardly any food, bearing what was clearly the heaviest pack in the expedition. He was quiet and patient, a stark contrast to the grim-faced corporate guides literally pulling their charges up the mountain, and described himself as risk-adverse. Incongruous as this may seem for a professional alpine mountain guide, there was clearly truth in it. In silent moments you could almost hear Brandon’s brain humming, chewing through the calculus of our chances as our collective will pushed against the mountain. He described hours spent pouring over accident reports and YouTube videos of disasters and rescues alike. Taking on the responsibility of training us in avalanche response and alpine safety, he imparted both a sobering seriousness and self-assured calm on the group. Under his tutelage, we learned to arrest a fall on the icy glacier with our trusty ice axe, to scan the debris field of an avalanche with a beacon in a sprinting zig-zag, and to dig in to the buried victim of an avalanche rather than down. When I stabbed myself in the leg with the spike of my ice axe (putting a hole in brand new pants, despite my $100 investment in gaiters that aimed to avoid this very thing), Brandon seemed to pull Tenacious Tape out of thin air. For like Julie, Brandon was keenly aware of our needs and jumped at any opportunity to make our lives easier.

The third guide was Cody, the youngest of the group, but the most experienced on Rainier (Brandon had summited for his first time less than a month prior to our trip). He was a vocal Buddhist, and lent a peaceful spirituality to our alpine rituals, burning Nag Champa during our rehydrated dinners and leading simple – but earnest – pujas before big pushes on the trail. Despite the wisdom that surpassed his years, Cody radiated a contagious energy, a byproduct of his love for the natural world and the grateful disbelief that he got to scale mountains for a living. He was the social glue of the group, eager to chat with anyone about philosophy, biology, music, climbing, medicine, meditation, or any other subject you were keen to submit. Somehow, even in the most arduous moments of our endless climb, his enduring enthusiasm never wore out its welcome. Like his colleagues, he was an inspirational example of patience, willpower, and kindness as our steps grew slower and gripes louder.

Danny captures Tiger, Tim, Andy, Cody, and Julie in his signature selfie

In the flurry of emails that circulated prior to our trip, the second day of the expedition was described as a “rest day,” intended to let our feeble, squishy, organs acclimatize themselves to the harsh realities of life above 10,000 feet. In reality, the word “rest” was here clearly misapplied. The day started innocently enough, the guides boiling more water while reminiscing about other times spent boiling water. Once, Brandon said, they had hosted a few "Georgia Boys” on the mountain. “Big guys, but strong.” The water boiling responsibilities has apparently pushed the guides to the brink of madness, with empty Nalgenes piling up faster than they could be replenished. For our part, we moved through our water at a slightly more reasonable pace, though Andy was playfully belligerent over his need for fresh coffee. The man was unapologetically addicted to caffeine and, more specifically, bulletproof coffee. He adores Ancient Organics Ghee for this purpose - insisting that I bring a healthy supply for the expedition - and though we ultimately decided against dragging glass jars of the stuff up the mountain with us, he coated the inside of his mug with enough ghee that he was able to supply himself for several days on residue alone. After coffee, Danny led the group - and a few stragglers from around camp - in some morning yoga on Camp Muir’s small helipad. Though it was obviously the staging point for many an emergency rescue, the helipad was more commonly used for airlifting 55-gallon drums of poop off of the mountain. It was one of a few structures at Camp Muir, all built in the style of the century-old guide hut and bunkhouse, scavenged rockfall framed with logs and cemented together with mortar. After the yoga, however, all semblance of rest went the way of airlifted poop, and we stowed our tents and packed our bags to relocate to high camp. Anna seemed to be getting sicker, and had skipped yoga, but she dutifully strapped on her pack and affixed her crampons for our first steps into technical terrain.

From this point onward, we moved as two four-person rope teams. Trekking poles stowed and ice axe in hand, we snaked our way up the glacier with about five meters of static line between each climber’s harness. In steep, rocky sections, a prussic (slide and grip knot) would be used to shorten this distance and lessen the danger of rockfall. No more than 100 yards from camp, we crossed our first crevasse. Though a casual step easily spanned the 10-inch gap, we still called out “crossing!” and “across,” partially to practice for more dicey crossings ahead, and partially out of respect for the depth of the thing, which - though narrow - stretched hundreds of feet into the ice below us. We crossed several additional crevasses as we traversed the cratered snowfield, then climbed an iceless section of rock. Here we stopped to marvel at a gushing waterfall of glacier-melt, the color of chocolate milk, which was dislodging toaster-sized rocks with alarming frequency. This was neither the first, nor the last, time that I was struck with the fleeting nature of Rainier’s alpine environment. In rock climbing, I am accustomed to laying hands on stone that has sat unmoved for millennia, if not eons. On historic routes, one can clip pitons driven into the rock decades ago by the revered forefathers of our sport. On a glacier, however, everything is transient, temporary, and temperamental. The trail that we climbed was vastly different than the one Brandon had taken just weeks prior, and in fact would again be different on our descent less than a day later. At every opportunity, Brandon prodded other guides, climbers, or rangers for information. Was there a ladder up? Had the cornice collapsed? Where did the high trails converge? He listened attentively to every response, redrawing the map and the itinerary in his mind, plotting our point on his invisible graph of safety and speed.

Anna on the glacier at sunrise

Though the hiking was slow, the afternoon required only 1100 feet of climbing from us, and we reached Ingraham Flats with the sun still high in the sky. This time around, tents were dug in deeper and stakes buried under piles of snow, as the high camp was more exposed to the wind and we would be leaving our tents here during the push for the summit. Ingraham Flats had no permanent structures, and from here on out we were entrusted with “blue bags” for ferrying waste off the mountain, so we ate an early dinner contemplating digestive cause and effect with a weight rarely afforded to the subject. While the guides busied themselves boiling snow, we settled into our tents around six o’clock to try to scrounge a few more hours of rest. At first, it seemed like sleep would be impossible. Basecamp for a joint expedition between National Geographic and NASA was set up nearby, testing equipment that might one day explore underground Martian lakes. They were receiving a fresh batch of scientists, many of whom seemed to be reuniting after much time apart. Nervously contemplating our chances on the mountain, the weather, Anna’s condition, I listened silently to their backslapping, to the tour of their camp, and with regular interval, the cracking explosions of not-so-distant rockfall.

Eventually, sleep did come, but it was not to last long. Cody roused us at 10 PM to begin final preparations for the summit push. Our “rest day” was officially over. Anna downed some more pseudoephedrine and we rushed to organize our gear and rope up, Brandon hurrying us along to stay ahead of a trail of climbers pushing up from Camp Muir. Unnatural as our early (or late?) start seemed, most followed suit. It is extremely dangerous to travel on the glacier during the afternoon, as warming temperatures dislodge rocks previously locked in the snow and shelves of ice pull apart to form new crevasses, so our timing was intended to help us reach the summit and descend before this point. Of course, in the fog of our fatigue, we didn’t consider any of this specifically, we merely slipped into autopilot and trudged along behind the gentle tug of our rope team.

The air was still, but cold, and for the first time we set out looking properly dressed for an alpine expedition. We had stowed layers of down clothing at the top of our packs and any time that the teams halted, these were hastily extracted to prevent our core temperatures from dropping too low. Once on the trail again, however, these layers had to be removed, as the climbing had become much more strenuous and one could easily overheat. Not far outside of camp, we started up a stretch of exposed rock, a steep, chossy formation known as the Disappointment Cleaver. True to its name, this section proved one of the most difficult of the entire expedition. The rock was incredibly loose, and every step sank and slid backwards under our weight. Crampons made crossing this terrain even more difficult, directing the force of your steps in unpredictable ways and threatening to steal a lazy footfall from underneath you. Everywhere, softball to microwave-sized boulders sat beside - or directly on - the trail, so precariously balanced that they almost seemed like intentionally-laid traps. Physically demanding as the trail was, the mental challenge was by far the greatest crux of the Cleaver. The trail ascended a steep set of switchbacks, so knocking a rock loose could maim or kill a climber below. Each step had to be made carefully, with your full weight held in reserve. In the near total darkness, we scanned the path in front of you for these hazards, tensely awaiting the unmistakable sound of stone sliding against stone or, even worse, the shouts of “ROCK!” from parties above.

Crevasse Crossing in two rope teams

At the top of the cleaver, the route typically takes a direct westerly route up to the cone of Rainier’s summit. However, rising temperatures over the last few weeks had created a hazard along this route that was impossible to ignore. The “Tsunami” was a teetering curl of glacial ice overhanging a couloir, a 100-yard gauntlet guarding the only path on this side of the mountain, threatening to drop at any moment. When Brandon had summitted Rainier a few weeks prior, he had described this path as “puckering” and attempting it now, after even more of its support had melted away, was beyond reason. Instead, guide companies had trod a new path, descending slightly and wrapping north along the mountain, eventually meeting up with another established trail to the summit. While a welcome reprieve for our already-burning legs, this detour ultimately added both distance and elevation to our summit push, and the thought compounded a creeping sense of dread that was welling up in me.

Still climbing in the dead of night, we pushed upwards and upwards, settling into a sort of trance fed by our bizarre environment. The icy switchbacks were cut through endless fields of penitentes, jagged pillars of ice resembling man-sized colonies of coral. Created by the sublimation of glacial ice directly into water vapor, these otherworldly structures take their name from their tendency to form facing the sun, as if bowed in penance. They left little opportunities to diverge from our chosen path, and we fell into rhythm with the switchbacks, wordlessly stepping over the rope and shifting our axe to the uphill hand with each reversal of the trail until a tug from a slowing teammate on the rope behind startled us out of our stupor. When the going became steeper, or the walls of ice grew taller around us, we would change our hold on the axe, no longer gripping it by the head, as a cane, but by the shaft, swinging it pick-first into the snow. In either case, it was rarely seated firmly in the ice, and even missing your plant altogether would not necessarily precipitate a fall. Rather, the axe sort of floated along by your side, tapping the ice as it sloped upwards, a gentle reassurance that the world was still there beneath your feet. The prevailing sound on the trail was the crunch of ice under the spikes of our crampons, but even that faded away as the hours pressed on. In its absence, I began to notice the peculiar noise that the shaft of the ice axe made in the moment between dropping the spike into the snow and removing it, as you stepped past its temporary fulcrum, tilting it like the hand of a clock jumping from eleven to one. The sound was an unlikely sort of slow squeak, not unlike a playground swing swaying in the breeze.

I can’t say how long I spent pondering this sound, spinning the aforewritten paragraph in my mind so many weeks before I’d commit it to type; time seemed to stretch and skip in the darkness. Occasionally, we’d pause to catch our breath and marvel at the view. While the moon remained hidden behind Rainier’s still-imposing shadow, the stars shone brilliantly in the thin air. On the horizon, you could see the shimmer of the Seattle metro, surprisingly close given our feeling of remoteness. Impossibly far up the mountain, an eerie train of glowing headlamps bobbed slowly upwards. As we rounded the Eastern face of the mountain, the sky took on a faint red glow, and soon after we lifted weary hands to toggle off our headlamps. While my lamp would serve no further use for the day, I dared not expend the energy to actually divorce the thing from my helmet. By this point, I was brutally exhausted, deprived of sleep, calories, and oxygen. Anna voiced no protest, but it was clear that she was digging deep for the will to continue. Already, Brandon had taken us aside for a check-up, explaining that the rope team’s current pace would not put us on the summit in time. Though he didn’t say it, the subtext was clear: “Are you guys gonna make it? Do we need to turn around?” We had steeled our resolve and given Brandon our understanding nods, but now I was beginning to waver.

As the sun rose on Sunday morning, we gained the Emmons Glacier and began our final push for the summit. The climbing became steeper, and the intersecting trails put parties close on our trail. At 13,500 feet, I started to receive some troubled glances from our guides. The altitude was wearing mightily on me, and my vision became spotted with little glowing auras. Twice, I swallowed my pride and gasped for a quick break, pulling the team off the trail and secretly praising the climbers that nipped at our heels as we waited for them to pass us. Still, we were too close for me to possibly consider surrender. If I had made it this far, a few more steps would certainly not kill me. We pressed up a particularly steep section, clipping our rope into pickets hammered into the snow to protect our team, then gained a large flat snowfield just below the summit. It was now six in the morning, and the sun shone brightly on us. The final 100 yards were free of snow, and I worked my way up the dusty trail a dozen steps at a time, falling to my knees and gasping for air more times in this short stretch than I can now believe. Anna mustered only the most meager encouragement, patting my foot as she passed me by, now free of the rope that had kept her in line behind me. I stumbled to my feet behind her, and with a few final steps at last stood atop Mount Rainier.

As we reflected on the climb later that day, Andy would describe the summit as “kinda weird”. The first time he had reached the top, he had been overcome with emotion, brought to tears by the weight of the accomplishment and the tragedy that had set his climb in motion. While we were certainly ecstatic to have reached our goal, I think what Andy meant by this was twofold. First of all, we were quickly chased off of the top by the weather (now that we had stopped moving, the dusty winds quickly chilled us to the bone and would occasionally threaten to knock you off your feet). More importantly, I think Andy was vocalizing something that we all felt, that the summit was but one tiny part of an adventure that, even at its most bleak and desperate, was at every moment a beautiful and revealing experience. As I look back on the expedition now, I rarely contemplate our summit. Rather, I think back to that breathtaking moment when the blood red sun first peaked above the horizon. I remember the careful measurement of our steps meant to keep the rope between us taught and the faint, but proud smile on Anna’s face when I would turn to check on her. I remember Brandon’s lessons, Julie’s stories, and Cody’s words of inspiration. I remember Andy smearing zinc so thick on his lips that he looked like a powdered donut fiend. I remember Danny duct-taping his phone to his selfie stick to get the perfect shot. I remember Tiger stowing rocks in people’s packs, then laughing too hard to get away with it. Mostly, I remember Rainier, and the shared moments of monotony and hilarity, pain and pride, despair and triumph, and that brief, uncompromising look at who we are and what we are capable of.

My time on Rainier has left me with a profound gratitude that I will carry with me for the rest of my life. I am forever indebted to Andy, for his vision and inspiration, to our guides, for their wisdom and compassion, and to our partners, for their camaraderie and motivation. I am grateful for the mountain, which allowed us to pass unscathed, for my body, strong and healthy enough to undertake this challenge when others cannot, and for my incredible girlfriend and climbing partner Anna, who drives me to dream, to persevere, and to live a life for the benefit of others. And of course, I am grateful for our donors, who gave us the opportunity to test ourselves in and incredible new way, and the chance to prove that climbing is not only a selfish pursuit, but a force for good in this world. From the bottom of our hearts, thank you.

If you would like to support Climb for Hope, please visit www.climbforhope.com or donate at: www.crowdrise.com/climbforhope

0 notes

Photo

New Post has been published on http://adventurewithryan.com/2017/09/07/mount-rainier-national-park-washington-state-u-s-a/

Mount Rainier National Park, Washington State, U.S.A.

Today I wish I hiking Mount Rainier insteas of being stuck 45 floors up in the finacial district of NYC.

Mount Rainier National park is located about 50 miles South-East of Seattle, Washington. It is located on the most North-Western corner of the United States on the Pacific Ocean, excluding Alaska. Mount Rainier is the 5th oldest National Park in the United States of America. The park is over 225,000 acres large and includes the monstrous 14,411 foot (4,392M) active Mount Rainier Volcano, in which the park is named after. Within the National park there are valleys, waterfalls, meadows, old-growth forests, and more than 25 glaciers (including the largest in the United States outside of Alaska). As I went over yesterday, I am debating with myself on moving to Seattle for a year before I start my world-travel business. While I am in Seattle, I will definitely be exploring Mount Rainier National Park on multiple occasions.

The climate in the Seattle area is pretty consistent year round. Due to its unique geographical location with the weather streams, extreme heat waves are rare as well as very cold temperatures. During winter months, temperature averages from 36-45 degrees Fahrenheit, and during the summer month’s temperatures average from 56-76 degrees. However, this weather can completely change once you head inside the National Park. Once you begin gaining elevation in the National Park, temperatures begin to change. The average during the summer months is in the range of 42-63 degrees Fahrenheit (6-17 Celsius) but can reach into the 90’s(F) at some points. The average during the winter months ranges from around 20-34 degrees Fahrenheit (-5-1.5 Celsius) and can hit extreme lows into the teens (-15F for example).

How to get there: Depending on which part of the park you want to explore that day, your entrance and your route will change. The two main roads that get you to the park from Seattle are route 165 (North-west entrance) and route 7 (turns into 706) coming into the South-west entrance. They take about the same time to get to. There are roads that travel through the central parts of the park, however do realize that it is still a national park, and you must park then hike to get to most sections worth exploring. Please use GPS to navigate based off of your preference.. The United States has almost all roads in the country mapped out at this point.. Use it to your advantage.

Wildlife: Mammals that inhabit this national park are especially the cougar (mountain lion), black bear, raccoon, coyote, bobcat, snowshoe hare, weasel, mole, beaver, red fox, porcupine, skunk, marmot, deer, marten, shrew, pica, elk, and mountain goat. The mountain goat is one of the iconic animals in this park and are only commonly found when you travel above 2,000 Ft. in elevation and is most commonly found above 5,000Ft. in elevation. Refer to here for more information on where to see mountain goats in Mount Rainier. The common birds of this park including raptors are the thrush, chickadee, kinglet, northern goshawk, willow flycatcher, spotted owl, steller’s jay, Clark’s nutcracker, bald eagle, ptarmigan, harlequin duck, grouse, peregrine falcon, gray jay, golden eagle, grosbeak and finch. Bird watching for large birds-of-prey can be very rich and rewarding if you plan your trip for the Spring – early Summer months.

What to do while here: What brings the majority of people to this park every year is mainly hiking, site seeing, photography, snow skiing in the winter, bird watching, and climbing the Mount Rainier Volcano itself. There are hundreds of hiking trails all throughout the park. Paradise is the most popular destination in the park. There is a historic Inn located in this region of the park as well as dozens of famous hiking trails including the Skyline trail. Paradise is known as the snowiest place on Earth, reaching over 1,000 inches annually. Longmire is another popular destination in the park due to having 178 total campsites throughout the area as well as having its own visitor center. This is the main starting points for many people as well as the famous Wonderland hiking trail. For more hiking try heading over to the Sunrise area of Mount Rainier National Park. From here you hike the Mount Fremont, Burroughs Mountain and Sourdough Ridge trails, as well as visit some iconic meadows in the Springtime, and get to view the Emmons Glacier. For snow skiing in this area, the Mount Baker Ski Area is where I was told everybody goes near Mount Rainier National Park due to its insane annual snowfall of over 1,000 inches. (closest ski resort to Mount Rainier).

Hiking the Mount Rainier Volcano: Over 10,000 attempts are made to hike / climb to the top of Mount Rainier every year. There is only a 50% success rate of actually reaching the peak who individuals who attempt the climb. Most of the lack of success is due to weather patterns as well as lack of physical condition for underestimating the climb. The hike will take approximately 2-3 days to reach the peak depending on how fast you can climb. There are campgrounds located throughout the climb and if you pass the high camps, they require you to purchase a climbing pass and register (mainly to keep track of individuals who may not make it back). FYI Climbing teams require experience in glacier travel, self-rescue, and wilderness travel so DO NOT under-estimate this climb.

Recommendations: For all smaller sized National Parks (Under 250,000 acres) I recommend 4 days and 3 nights while staying within the park at either a local campground or on your own via tent or camper if allowed by the park. 1 night in this park must 100% be spent climbing to Camp Muir. This is the highest non-technical point (10,080FT) in the state of Washington and most of the United States. This hike is over 8 miles round trip, and includes 4,660ft. of elevation and has the most rewarding of views. The next two days I would spend exploring Paradise as well as the Sunrise regions of the park. My recommendation is to stay within Longmire region and maybe start with a warm-up hike every morning as this is one of the easier hiking areas. Spend the nights enjoying the night-skies and having campfires while drinking beer; after all isn’t this why you came here?! Spend the 4th day filling your time with anything you and your accompanied persons want to do.

If anyone has ever been to Seattle or lives(d) in Seattle, please leave any tips or information!

Thank you for reading. Please like, share and subscribe for more daily places in the world that I am currently dreaming of being at rather than work.

#blog#blogger#exploring#Hike#Hiking#National Park#National Parks#nationalparks#Nature#Outdoors#Seattle#travel#traveling#usa#west coast#world traveler

0 notes

Photo

Today climbing rangers, working in conjunction with the park ecologist, made it up to Camp Muir to repair the weather station that lost communications at the beginning of January. Park scientists manage long-term data collections, including air quality and weather, that are used to determine the status of trends of park resources.

Learn more about National Park Service monitoring efforts at https://www.nps.gov/im/nccn/index.htm

NPS/S. Lofgren Photo, 1/29/2019. Description: A man in a yellow jacket holds an antenna piece and looks up at a antenna tower on a rocky, snow-covered mountain slope. ~kl

#Mount Rainier National Park#Mount Rainier#Camp Muir#weather#weather monitoring#air quality#weather station#inventory and monitoring#North Coast and Cascades Inventory & Monitoring Network#mountain climbing

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

When you think of national parks, do you think of science?

How about Mount Rainier National Park? What science specialty comes to your mind?

Is it volcanology, the study of volcanoes? Or how about geomorphology, the study of landforms and the processes that shape them? But there are many more: biology and botany (wildlife and plants), aquatic ecology (underwater study of plants and animals), archaeology, just to name a few. Besides National Park employees, there are many researchers from universities and colleges that apply to study in the park.

There are also many opportunities for to get involved in Citizen Science. Learn more at https://www.nps.gov/mora/getinvolved/volunteer.htm

Have you participated in citizen science in the past, or learned something new about science while in the park? What is your favorite Mount Rainier science? ~ams

NPS/Lofgren Photo. NPS scientist works on weather station at Camp Muir. 2013. NPS/Lofgren Photo. Preparing to sample lake water. NPS Photo. Hummingbird in researches hand for bird banding in the park. 2018. NPS Photo. Researcher works near rushing water to install river gauge instrument. 2018.

#science#volcanology#geomorphology#biology#botany#archaeology#national parks#mount rainier national park#research#citizen science#volunteer#findyourpark#encuentratuparque

88 notes

·

View notes

Text

Have you climbed Mount Rainier?

It’s a question a lot of park rangers get asked. A few of us have. Some, quite a few times. Whether climbing for work or recreation, it’s a question of training, endurance, skills (lots of them), equipment, and weather.

But it’s time to turn the tables. Have you ever climbed Mount Rainier?

What made the difference for you? Was it all the physical training that you put in making sure your body could take you to 14,410 feet above sea level? Was it the team you were with and how well you worked together? Maybe having all the skills down cold and using the right equipment? Or did reading the weather correctly make or break your attempt?

What’s your favorite story of climbing the heights of Mount Rainier?

For the latest information on climbing, please see our park climbing webpages https://www.nps.gov/mora/planyourvisit/climbing.htm , the excellent blog and very detailed information put together by our climbing rangers http://mountrainierclimbing.blogspot.com/ and check out the webcams at the high camps for the latest conditions https://www.nps.gov/mora/learn/photosmultimedia/webcams.htm

Please note that some of these pictures were taken within the last month but that conditions change quickly. Some photos are from last year. Thank you. NPS Photo (top). View from Camp Muir looking down Muir Snowfield and across the Tatoosh Mountains. Mount Adams and Hood are visible in the distance. June, 2020. NPS Photo (middle). View looking down Disappointment Cleaver towards Little Tahoma with sun rising behind. August, 2019. NPS Photo (bottom). Emmons route at bergschrund with tenuous ice bridge over crevasse. June, 2020.

#recreate responsibly#climb#mountain climbing#memories#mount rainier#mount rainier national park#national park#findyourpark#encuentratuparque#glacier#camp muir

40 notes

·

View notes