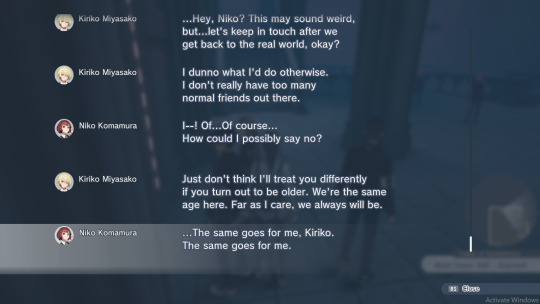

#my namesake

Text

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

A non-horsey friend sent this to me. I asked if it was any good, and she said it was out of her price range so she wouldn't know 😂

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

If you enjoy the worldbuilding, monsters and underground city exploration in Dungeon Meshi then I recommend playing Hollow Knight it's so good.

#literally my only caveat with this game is that there's an optional upgrading your sword side quest and once you complete it#the crafter asks you to kill him with the sword and you get an achievement if you do that which i think is fucked up#but also if you don't he does get a happy ending and you also get an achievement#dungeon meshi#hollow knight#my namesake#video games#📨

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Anouk Aimée et Sonia Rykiel

Prêt-à-Porter (Ready to Wear)

Dir: Robert Altman

#<3#my two favs#anouk aimée#sonia rykiel#my namesake#bts#prêt à porter#ready to wear#fashion#my edit

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

genuinely is this a comedy or a horror movie?? actually i don’t care. i’m watching it twice.

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

#MY NAMESAKE#OU GOD OH GOD OH GOD OH GOD OH GOD UP IN HEAVEN. LORD JESUS SAVE US. SAVE ME#OHHHHHH GOD IM GONNA PUKE EVERYWHERE. IM THROWING UP EVERYWHERE RN#OH GOS#OH GODDDDD OH GOD#LEAFY BFDI#LEAFY SAVE ME. SAVE ME LEAFY#I NEED HER TO KILL FIREY.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

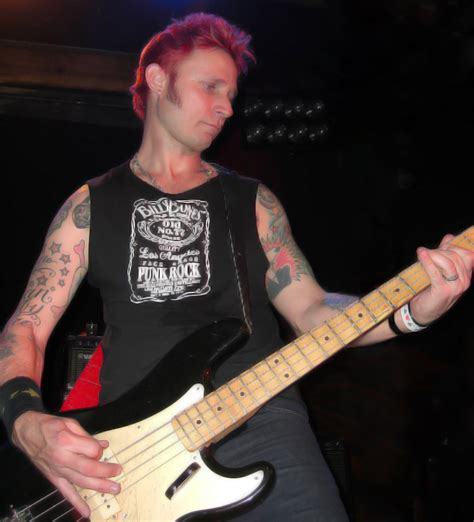

Every time someone posts DJ Crazy Times...

All I see is Him...

2011 Red Hair Mike Dirnt I Love You

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#film: while you were sleeping#while you were sleeping#sandra bullock#filmedit#that's my girl#my namesake#things i made

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

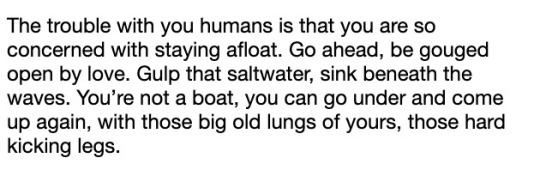

“The Buoyancy of the Human Heart” by Laura Lamb Brown-Lavoie

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

A living sun that brainwashed people into committing mindless violence? That sounds familiar...

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Joshua Tree Inn Room 8 oil painting by J. Clum

#haunting stuff#gram parsons#oil painting#the flying burrito brothers#emmylou harris#cosmic american music#my namesake#the byrds#grievous angel

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Struggle for Love: A Tale of Leah and Rachel

Night drops from on high over the plains,

The cool dews pour,

And the youngest daughter of Laban groans,

Tearing the thick braids of her hair.

She curses her sister and reviles God.

.

The main thing to understand about Rachel, from the very beginning until the end of the story, is that she was loved.

When she was a child, her father loved her the most. He loved her in the doting way that fathers have for young daughters, ruffling her hair and indulging her flights of fancy. As she grew up, Laban took pride in the way that she bloomed into modest loveliness and caught the glances of the young shepherds. Rachel was her father’s delight, and well aware of it.

Leah, too, loved her sister very much. They were best friends back then; different, of course, but united by sisterly solidarity and the joy of a youth spent together. They giggled over jokes and stories and embarrassments and nothing, and it did not matter that Leah’s wide-set eyes did not shine as beautifully as Rachel’s large, dark ones.

Sometimes, on hot, dry nights, Leah would lie awake in bed and wonder which sister’s love was better. Rachel had the luxury of carelessness; the surety of a love that came easy. She could afford to love generously, and she did.

On her worst days, Leah almost hated her: flighty, fierce, beautiful Rachel, who loved hard and received love effortlessly. Leah hated the way she always felt faded in her sister’s light. Sometimes, when she could bear it no longer, she would burst open and spit, you brat! you get everything! at her sister, only to regret it an instant later.

Yet in spite of all that, in spite of Leah’s worst days, she went on loving Rachel. It was a more complicated love than Rachel’s, and Leah did not know if that fact made it better or lesser than Rachel’s simple love.

When Rachel was a young woman, just on the cusp of marrying age, she watched over her father’s flocks, spoke pleasantly with the shepherds, and returned home in the cool of the evening to suppers with her family. Her favorite things in the world were running water, laughing with Leah, and when her father called her “sweetheart.” When Leah looked back much later, she would often wonder whether maybe if things had been different, her baby sister could have stayed that way forever.

But one day, when summer was half-spent and the sun was hot on the fields, Rachel went with the sheep for watering. That was the day that everything changed.

Jacob, their wandering kinsman, saw Rachel walking towards the well. She was a little disheveled, with wisps of hair escaping to frame her face, but to Jacob it only made her appear all the lovelier. When he saw her, he rejoiced that such beauty could be his own kin and he kissed her. He was strong and sun-tanned, and Rachel loved him almost at once.

Jacob had heard the voice of the God of their fathers. He had seen a ladder going up to the heavens, streaming glory, and it had changed him. Something in his demeanor proclaimed that he had seen angels; something about him, Rachel thought, bore the unmistakable mark of the Covenant that God had made to her great-uncle. She imagined that she could hear the voice of the God who made promises herself sometimes when she was alone among the sheep, but even more so when she was with Jacob.

“Seven years is like a few days because of my love for you,” Jacob told Rachel. Sometimes he said it with a wry chuckle, others intently, or almost ravenous. Always, Rachel smiled and hungrily tucked his love away in her heart.

Laban made Jacob wait and work for Rachel’s hand, but Rachel endured it eagerly. Seven years went by like a few days and Rachel passed out of proper marrying age with the promise of Jacob to sustain her. Leah was still unwed, but Rachel made herself believe that it didn’t bother her. Leah loved her, and Rachel ignored the fact that Leah would vanish sometimes midway through conversations and bite her lip when Rachel talked about the future for too long. Leah loved her and that would never change.

And Leah was happy for her sister, truly. Or at any rate, she worked hard not to resent Rachel’s happiness. Leah had no promises, no beloved. She had weak eyes and withering youth, however hard she tried to pretend otherwise. It was not the custom that the younger daughter should be married first, but Rachel was Rachel. Of course, she would not be made to wait. She would leave with Jacob, and Leah would be left without a future in her father’s house. Rachel, the sweet lamb; Leah, the ugly cow.

When she complained to her father about the horrible unfairness of it, she did not expect him to listen. When she cried out in desperation, but it is not the custom for the younger to be married before the elder! she expected to be ignored.

Seven years passed like a week and then the unthinkable happened. Rachel’s father, who had always loved her best, gave her husband away to her sister. Leah’s father, who had always loved her the less, gave her Jacob.

Leah went to Rachel the next morning with a heart full of complicated love. She went with a list of explanations, but without apology. There was pain in her wideset eyes, but Rachel was practiced in ignoring that. Leah was supposed to love her more than this.

Jacob, of course, was enraged at Laban’s trickery. He would not be satisfied with the cow when he had been promised the lamb. Both sisters were (naturally) absent while husband and father bartered them like livestock: Rachel, in exchange for another seven years hard work.

The years would be longer now, but Jacob loved Rachel, and that was something like a balm to her heart. Jacob worked another seven years to make her his wife; he worked for her fourteen years after that sun-baked day in the pasture. Rachel married Jacob second because she had been born second, but she consoled herself with the knowledge that Jacob loved her first and best.

Now, Rachel and Leah lived under the same roof again, but Leah would not speak to her. “I miss you,” Rachel tried to say. “Can’t you just apologize and go back to being my sister?”

Leah started picking her cuticles. She slept fitfully and ground her teeth at night. Every time she saw her sister approaching, Leah contrived an excuse to go elsewhere, anywhere. She had been second to Rachel her whole life. Now it would never end.

Rachel was beloved of her husband, but it seemed that Leah was beloved of God. She bore four sons in as many years and rejoiced that God had smiled on her, wondering if Jacob would finally call her “beloved.” Yet even when Leah placed her fourth babe in his arms, it was Rachel his eyes sought when he looked up.

Leah wondered if she would ever stop feeling like an imposter in her own home. She ignored her sister entirely, except in lonely, crushing moments when she thought about their childhood together. When they were girls, they had gone walking to the well with their shoulders bumping one another back and forth, bickering and sharing secrets.

In another room, Rachel remembered the same things. Sometimes, she missed her big sister so much that it was physical pain. Yet now Rachel saw Jacob’s hair, Jacob’s eyes, Jacob’s chin in her sister’s children and her stomach turned over.

“Give me children,” she told Jacob, “Or I shall die!”

“Am I God?” Jacob asked her. “Only he can give you children.” He said it fiercely, angry and sad because he wanted Rachel to have children too. That was maybe the worst part of it all. Jacob looked at her—Rachel, Laban’s daughter, who had child-bearing hips despite not bearing any children, who liked laughter and water and lace; flighty, fierce, barren, and he went ahead and continued to love her.

Rachel tried to armor herself against the contempt of her household. The whispers and badly-hidden chuckles no longer surprised her. Still, she would not deny the shame she felt when the servants pointed and said, “The Lord will never open her womb.” Each time, Rachel squared her shoulders and went on.

Jacob’s love and her own shame: that was why she sent him Bilhah. It did not seem like a choice at the time. What else could she do? Bilhah bore Rachel two sons to raise and to love, and Leah stopped bearing.

But Leah was not ready to concede defeat. For the first time, she did not feel inferior to her beautiful sister. She felt strong, poised for triumph.

Perhaps that was why she sent for Zilpah.

It was the argument over Reuben’s mandrakes that finally got them speaking again, albeit not in any semblance of civility. Rachel was still desperately aching for children of her own blood, so she went to Leah with as much humility as she could muster and asked for some of her mandrakes. Leah’s face was ashen when she responded, “Is it a small matter that you have taken away my husband? Would you take away my son’s mandrakes also?” and Rachel heard the accusing voice of her big sister between those cold words. You get everything.

Not everything, Rachel thought. Not nearly enough. She traded a night of her husband’s company for Leah’s mandrakes and Leah conceived again. Only this time, Rachel conceived too.

Rachel thought about Jacob’s Covenant faith all through her pregnancy. She thought about the way Leah had named her children with praises through gritted teeth and wondered where she had found the strength for it. Rachel had named Bilhah’s sons for God’s judgement and her own temporary victory in wrestling with her sister. Rachel could be greedy and selfish; she could no longer pretend that she wasn’t. So, when finally Joseph was born, Rachel named him for her greed. “May Yahweh add to me another son!” she said as she looked down at the baby in her arms. One was not nearly enough.

Jacob doted on Joseph and Rachel heard her sister whisper, you got everything.

Rachel named her second baby for her grief. Benoni was too innocent a thing to be saddled with such a heavy name, but she could not remember the last time she felt light. She did not have enough breaths left in her lungs to praise the Lord as Leah had done, through gritted teeth. Grief was something tangible and immediate, the way love was.

Rachel held Benoni tight in her arms and wished for the strength to hold him tighter. She fixed her dizzy gaze on his eyes, which were her own dark ones; his hair, Jacob’s fine black; his mouth, which echoed Laban’s, which Rachel still loved despite everything; his chin—Leah’s. Rachel looked up and saw her sister’s silhouette above her.

“Go away, Leah,” she said hoarsely. “I loved you once and then I resented you, and I’m not strong enough to think how you must hate me now.” Leah knelt beside her sister and rested a hand on Rachel’s shoulder. This was not hatred; it was something else entirely. It was complicated.

Leah did not move to go, but she was silent for a long time. Rachel’s eyes were beginning to drift closed when Leah finally spoke. “I’ll look after them. Dan and Naphtali. Joseph. Benoni. I’ll love them as well as I can.”

Rachel was out of breath for words, but she had so many left to say. She wanted to say, We were both bitter and angry and I missed you so much. Why didn’t we try—try harder? Leah, I love you! Didn’t I love you enough for that?

Instead, she whispered, “Good. And Jacob—look after him too.”

Leah laughed, wet and ironic. “Yes,” she said, “Jacob too.” She kissed Rachel’s cheek, which at that moment was gray and unbeautiful, streaked with sweat.

For a moment, Leah imagined that they were girls again, laughing and bumping shoulders on the way to the well. Oh, God! Her baby sister was dying, and they hadn’t laughed together in years.

Jacob mourned his beloved Rachel there at Bethlehem, loudly weeping as he saw her buried and a pillar erected over her tomb. Leah held his hand, and she wept too.

The thing to understand about Leah, from the beginning until the very end of her story, is that she was loved.

.

In the valley the clear spring,

The joyful look in Rachel’s eyes,

And her voice like a bird’s song.

Jacob, was it you who kissed me, loved

Me, and called me your black dove?

.

(Poetry by Anna Akhmatova)

#this is probably the piece of writing that i'm proudest of and i've been back and forth on posting it for a while#i love the tragedy of this story#my namesake#let me know what you think ;)#posting under the cut so that i can take it down if i need to#not sure why i would need to just feels sensitive#like i think it's okay to reblog. i just don't like the idea of not being able to take it back if i want to#idk#tonight I want to share something#Leah stories#Bible humans#pontifications and creations#no one will ever walk the earth so close to you

38 notes

·

View notes