#my town's local asylum is about to gain a new patient SOON

Text

a nightingale sang in berkeley square being aziraphale and crowley's song, the nightingale representing what they've felt for each other through the years, crowley being the one to say it out loud and address the fact that the nightingale was there, that it was real and then saying that neither of them can hear it now, aziraphale fully taking in what crowley meant, aziraphale looking away, aziraphale about to cry, crowley kissing aziraphale in a desperate attempt to mend things, knowing things were over but still trying all the same, aziraphale saying "i forgive you" but for what? for kissing him? for confessing only when everything was too late? for saying there were no more nightingales? and then we got crowley saying "don't bother" and walking away but still waiting outside to see aziraphale leave for heaven and maybe it's because he wanted to see aziraphale for as long as he could before they parted ways or maybe it's because deep down he was still hoping for things to change — either way i am GOING TO THROW UP

#girl what the hell#my town's local asylum is about to gain a new patient SOON#sorry for this stream of consciousness ass post the spirit of james joyce is overwhelming sometimes#mom the queers are at it again#mr gaiman i am in your walls. under the cement you walk on. i am There#i cannot cope#i cannot deal#i cannot do this#i cannot#meltdown#spiraling#breakdown#good omens#aziracrow#aziraphale#crowley#david tennant#michael sheen

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Working from Life - our Play by Play talk!

As usual we’ve taken a little while to post another update, but things are going super well! We feel like we’ve been reaching some pretty exciting milestones on Wayward Strand recently, and are moving steadily onward.

Before getting into the talk, we’ll be Officially Announcing it soon, but we’ve added a page on our website on which you can subscribe to our newsletter! If you want to get notified about key bits of news (including when Wayward Strand is released), or you’d like to get emails with some behind the scenes stuff, head over there and sign up!

And in the meantime, here’s the video and transcript of a talk that Goldie and I did at Play by Play in Wellington, New Zealand earlier this year. It covers a pretty wide range of topics, but it speaks to each of our influences in working on Wayward Strand, as well as what we’ve learned from the process of creating it thus far.

youtube

Transcript

Jas: So Goldie and I are going to talk about this topic mainly in terms of the game that we're both working on, Wayward Strand. You don't need to know too much about it before we get started, except for the fact that it's an interactive story set in a small coastal town, in southern Victoria, from the 27th to the 29th of January, 1978. Oh, and that it's set on an airborne hospital.

It's an interesting mix of elements - so how did we get there?

When our team-mate Russell came up with the initial idea for Wayward Strand we talked a bit about where it could be set - at that point we had the airborne hospital, but it could have been set anywhere, and in a real place or a fantasy one.

At the time I'd been listening to short fiction podcasts - particularly the New Yorker fiction podcast, on which a writer chooses a story from the archives to read and discuss. After the reading, the writer and the podcast host, Deborah Treisman, often speak about the author of the piece, and discuss how the story links to the author’s life and history. I was fascinated by how many of the stories being read were set in locations and at times that had personal significance to the author.

To highlight an example, Stephanie Vaughn's stories that have been read on the podcast, Able, Baker, Charlie, Dog and Dog Heaven, from her collection Sweet Talk, are both from an army brat’s perspective, exploring daily life on military bases, and Stephanie Vaughn herself grew up on military bases; her family followed her father around to these bases through the years of her childhood. However, none of her stories are autobiographical - they're drawn from her life, but not based on her life.

Listening to her stories really awoke in me a realisation that this was something you could do - that I could do - set a story in a place and time that you have a personal connection to - and how that could be interesting and powerful. I’m going to pass across to Goldie, but I just want to say to read Sweet Talk! It’s incredible.

Goldie: One of the most captivating and earliest exposures for me of neorealism in indie art was when I discovered American Daniel Clowes’ long-form graphic novel, ‘Ghost World’. Ghost World follows Enid Coleslaw and Rebecca Doppelmeyer, two cynical, pseudo-intellectual teenage girls recently graduated from high school in the early 90’s. What really captured my curiosity was the way that the novel, as well as the 2001 film adaptation, follows the two teens as they spend their days wandering aimlessly around their unnamed American town, criticising popular culture and the everyday Americans they encounter. Especially notable in this small town, and still present in our towns and cities is the slowly encroaching franchises which smother their town’s individuality. The story regularly highlights characters who are almost the antithesis to the normalisation of behavior and social exchange. It’s hardly revolutionary, but was quintessentially realistic; a light shining on the quirk of the everyday.Ghost World was hugely influential on my expectations for myself as an artist, it taught me how to appreciate the small stuff which gets ignored by Warner Bros, Disney, Marvel and local mainstream media. Realism, in games, has usually meant photorealism - whereas realism or neorealism in literature, art and film has constantly been more about social context, historical actuality and political commitment to progressive social change. Robert Yang’s recent short article on Realism in games is worth a read to cover this.

When I arrived at uni, eventually, to study game design it was surprising to me to see that there wasn’t yet much exploration of the ‘slice-of-life’ genre in games, and even less social realism in games. There was some, the closest example I came across with glee was Dys4ia by Anna Anthropy, who used games to talk about her experiences with transitioning. Likewise, when I discovered Escape from Woomera, Katherine Neil’s extremely confident Half-Life mod which explores Australia’s ongoing disgraceful treatment of asylum seekers, I nearly exploded with hope for games. ‘Papers, Please’ by Lucas pope is another popular example of a reality-informed game for political expression. Richard Hoffmeier’s Cart Life, too, is perhaps the ultimate realist game, but to get into something as breathtakingly perfect is going to require a different talk.

Anyway, at uni, I decided with my friends to make a game inspired by Daniel Clowes, and the mundane, and set it within my fictionalised memories of growing up in Melbourne. We called it Movement Study 1. I chose Australian artists like Howard Arkley to inspire a lot of the visual design on key parts of the short game, knowing that in the 70’s he had also tried to extract the beauty from his mundane suburban Melbournian experience.

Like Ghost World, it focused on a loosely autobiographical version of myself through two characters who wrestle with their evolving post-high school friendships. I just wanted to see if it worked in Melbourne and of course, it did. It was a successful project as far as our intention for it goes. Since then, in 2013, we’ve been lucky to see games such as Gone Home and more recently, PaperBark, set in and about the Australian bush, and Knuckle Sandwich, another Australian endeavour at personal expression through interaction, with less of a real-world setting but with so much auto-biographical content. I learned through practice that the games space, like literature and film before it, was ripe for real-world settings and stories. Since making Movement Study 1, I have worked on a handful of private, small unreleased games, illustrations and stories about the lives of people from Australia, including but not restricted to family history.

When Jason and Russell approached me about working on Wayward Strand, it was an instant fit. All they had to do was mention that they were wanting to create a game set in Australia in the 70’s and I was interested. Through exploring more about the history of the time and place, we have constantly been confronted with terrible stories of injustice, as well as a plethora of unique country-life aesthetics to draw upon, and have the benefit of the lense of contemporary awareness to know which points to focus on.

Wayward Strand is my second attempt, in a team, at writing and crafting a richly Australian story based on fictional characters, informed by stories and histories I have come across. Because of the depth of history - both healthy and frankly, fucked up, I don’t doubt that Wayward Strand will eventually prove to be a successful exercise in real-world fictional narrative games.

Jas: So we thought we should have a slide that breaks down what we see as the key benefits of setting a game in a real place and time. It’s important to know that many of these benefits apply regardless of whether your game has a strong narrative component or not!

The benefits we see are, in brief:

* If you make a game that’s set in a place that has personal significance to you, it’s likely that it will have significance to other people in your family and community as well, and they'll be able to potentially help with your research process. In our case we were particularly lucky with this, which Goldie will speak to later, but reaching out to your local community is how you can find people who are able to be great resources in this regard.

* Once you set your story in a real place and time, it provides a scaffolding for your story as you are building it - you are still going to be telling your story, but having it set somewhere specific is incredibly helpful for overcoming the blank page. It’s a real place! It exists, or existed, and you can keep finding out more about it, then using the results of what you find.

* Relating to that, a real place and time is a treasure trove for influences and idea-generating facts or stories - think of it as the most comprehensive lore you could possibly imagine, and there are likely to be virtually limitless resources to draw from (we certainly found this anyway)..

* Finally, your work of art gains an immediate significance to real people's lives - the people who live in that place now, or lived there before, or have parents or ancestors who lived in that place. This provides meaning to your project beyond your personal creative impulses, and acts as a good incentive to actually finish what you've started - you’re now contributing to a continuum of cultural works about this place and time.

Goldie: Getting deeper in to the personal connections I am able to draw upon with this particular project, my mother Liz worked in the 70s, 80s and 90s as a charge nurse in Emergency Departments across Melbourne. She also grew up rurally, and has been an unparalleled resource for knowledge of the time and of experiences in hospitals. We’ve been able to base entire characters on her stories, as well as moments with almost all of the patients. Let alone the actual day-to-day running of the hospital. Vocal mannerisms, routines and expectations on the staff, behaviours of the patients. Ways for the staff to have fun, ways for them to get away with it. The hard parts and the sad parts. There were some things we couldn’t include, especially stuff which happens after dark in hospitals on slow nights such as crutches cricket, but learning about the culture of people working in these places at that time has been wonderful.

Like mum, my dad Jim was also involved in hospitals during his career- he was a senior health architect and was the lead designer on many of Melbourne’s large and small scale hospitals and health facilities. I grew up in a house full of reams of A0 paper with architectural plans for hospitals, as well as notebooks full of questions and thoughts which I never really understood. Approaching wayward strand as a designer, in the architectural mindset was definitely enriched because of this. Ship architecture on the other hand was less known to me- but luck has it that my grandfather, also Jim, was a ship’s engineer and his WW2 ship, the HMAS Castlemaine is still docked and accessible in Williamstown, Melbourne, and the public are welcome to tour any time. Merging hospitals and ships is pretty tough, though, so we’ll see how I go.

Another thing I have been able to draw upon is the experience I had with my dad in the last 5 years of his life. He died in 2016 after a long sickness which caused him the need to live in a handful of nursing homes around Melbourne. Visiting him every few days was pretty difficult after a while; nursing homes these days generally are unpleasant places, usually due to the tiny amount of funding available to them, as well as the task of managing older, sick and dying people of diverse backgrounds with differing care requirements. I spent many after work and uni afternoons with him updating him on how my life was changing, all whilst his was completely stagnant, and drawing ever so slowly to a close. He died about 5 weeks after I started working on Wayward Strand and I have squirrelled a huge amount of observations of the patients, the buildings, the routines and the feelings from those environments into the game. It’s been very healing for me, I think, to have had a project so immediately relevant to what could otherwise have been left to simmer. Knowing that the nursing home in our game is a slightly different type: luxurious, one of the first, and more like an optional living arrangement for some of the patients feels like a good thing. To really capture the greyness and frankly, macabre tone of a contemporary nursing home isn’t what we want to do with Wayward Strand…But knowing about it helps. Kind of like pushing an idea as far as it can go, and choosing which parts are gentle and true enough to include in a family-friendly video game.

Jas: I’m going to give a specific example that came out of talking to Liz which is a pretty minor spoiler - at one point we had a storyline that revolved around a character's desire to be euthanised, and that desire being blocked by the hospital staff. It made a bunch of sense to us when we thought of it and it's a topic we're interested in and initially wanted to explore in the story, but as we spoke to Liz she let us know that at the time - this is over 50 years ago at this point - euthanasia really wasn't the hot-button topic it is at the moment, and the hospital staff would basically euthanise patients if they desired it.

The staff used a euphemism for it - it was described as "making the patient more ‘comfortable’" - and the staff would just crank up the morphine and let them pass quietly in the night. This is not only a really interesting fact to know about our setting that has a lot to potentially explore in and of itself, but we've been able to change that character's story to be more suitable to the time, and to be more unique as well.

Now, instead of the storyline being very directly related to the hot-button topic - which is already being covered in other media such as the late great Terry Pratchett’s documentary Choosing to Die) - our storyline has become more about that particular character's struggle for empowerment, and being given the right to make her own choices.

Goldie: There’s something which belongs to the people when you use media, especially media traditionally used commercially, to depict realism. Making work which comments on reality can be a powerful historical tool, both as documentation and representative of large social issues. Take for example one of the most significant paintings from the early realism period - The Gleaners, an ever-long masterpiece by Frenchman Jean-Francois Millet completed in 1857. The painting depicts, in an unadorned manner, three peasant women gleaning a field of stray stalks of wheat after the harvest, which they will use to feed their impoverished families. It is a sympathetic representation of the lowest ranks of rural society- and in 1857 it was very- extremely- poorly received by the French upper class, who were the prime audience for paintings like this at the time. Even the middle classes, fresh on the other side of the French Revolution in 1848 were upset by the painting. To them it was a reminder that French society was built upon the hard labor of the working masses, and landowners linked this with empathy towards Socialism - very uncool, even scary at the time. The Gleaners as well as other paintings and works of literature from this period were instrumental in broadening the perspectives of entire generations, thus shaping the course of history to become more inclusive, fair and considerate. Even pieces such as the (slightly problematic) Pride and Prejudice, 1813, have used reality to create social commentary and critique. Whilst this isn’t literally my personal history, it has helped to shape the reality I live in. By now, it’s the norm, artists across all media are regularly drawing upon the real world for their work. To use music as an example, there was a fresh wave of social critique with the hip hop movement, as well as with the political American punk movement in the 70s. Avant-garde art in the early 20th century with movements like Dada and outsider art in Europe are also significant, and the list goes on.

Making art hasn’t always been, and isn’t always political, but it can be, and if games are art, we can and should go there when we can, especially when we have things to say. This is one of the reasons why amplifying voices which aren’t traditionally as loud as mine, or maybe yours, is something vital for large-scale cultural progress.

In the 70s in Australia, following consultations and through general knowledge, we can paint one picture of rural Australian life at the time. It’s been covered in movies like the popular Puberty Blues, which shows the awkward, difficult and painfully slow (and sometimes painfully fast) moments of growing up by the beach. It’s heard in music of the time, notably Australia’s rock and even punk music of the time was always the voice of a working class people, demanding better conditions, and poetically capturing the conditions of their everyday lives. We can see snippets of VASTLY celebrated Australian culture by watching football and cricket re-runs, even if they were (and perhaps continue to be) pretty bad news as far as toxic masculinity goes. Less discussed than sport culture in the public forum at the time were some of Australia’s more despicable histories- for example the government’s cultural treatment of women, queer people and most markedly perhaps it’s unforgivable and unforgettable treatment of indigenous Australians. In the 1970s this was still, and I think continues to be, shameful. When the team met with Land’s Council member Uncle Chris to discover more about being young and indigenous at the time, he and I had a blast talking about the music scene in 70s Melbourne - but we also uncovered some very hard truths which have helped us shape the experiences of another young character on board the ship.

Jas: In regards to indigenous consultation we also talked with Dan Turnbull from the Bunurong Land Council - he let us know stories of the Bunurong who lived and still live on the land where the story is set, and really gave us a primer on Bunurong culture and society from his perspective.

We initially got in touch with the Bunurong Land Council through Dakoda Barker in Queensland, and we didn’t really know what to expect, but it turned out that Dan loves games, has a great understanding of what we were going for, and was able to give specific, pointed feedback and advice.

One of the particular things we came to Dan about was that, as Goldie mentioned, we wanted to have a Bunurong character in the game - a young Bunurong man - but we were worried about the ethics and outcome for the community of having a Bunurong character without having Bunurong representation on our team.

But what Dan told us was, obviously it would be great for us to have representation on the team, but that we should still go ahead with it - that he sees it as a net positive thing, something that he's excited about as a Bunurong man, and he gave us some pointers and guidance for how to do it in a way that he'd find respectful and worthwhile, as well as letting us know how to get more Bunurong folks involved.

Now it's important to note that we shouldn't assume that he speaks for all Bunurong people, or that this is some "license" or grant to do this - but it means that, from a personal perspective, we felt more sure of ourselves in including this character, and had a better idea of how we could include him in a way that wouldn’t be detrimental to the Bunurong community.

Consultation isn't a box to tick off or something that you can use to make yourself immune from criticism - criticism is good, healthy and valuable, especially when it comes from people who are more marginalised or less privileged than you.

Instead, consultation is an ongoing process that empowers you to make your creative work more relevant to more people. Every discussion that we've had so far has given us further insight; more interesting elements of the setting to explore; and has enriched the final player experience.

Goldie: If you’re able to pile in to a car or bus with your team and visit areas you want to explore, absolutely do it. When I was making Movement Study, I originally wanted to set it where I grew up, in Port Melbourne. But as it turns out, my artist and I decided to meet in Brunswick which is a more common area for our generation to have grown up in- there weren’t very many kids in Port Melbourne and so it wasn’t as well-known as Brunswick. This was definitely the right decision, as multi-generations of Melbournians instantly recognised exactly where the game was set. When Adrienne and I went to Brunswick, we spent time walking around and taking photos and footage of the old houses lining the streets. Small details popped out - how the gardens were kept, where wheelie bins were stored, how much signage there was, the condition of the footpaths, leaf litter, how much traffic there was at the time of day the game was set…so much more. Even just to be able to grab a palette from the walk was useful. It made the biggest difference to the game I think of anything else we did, and so when Wayward Strand decided where might be best for our game to be set, we decided to head off on a short adventure.

We booked a house for the weekend and took cameras and microphones and notebooks, and planned visits to local historical societies and places of interest. We got a huge amount done just that weekend. Walking around on the windswept beaches and getting our boots wet in the sand, as well as climbing over sandbanks, eating fish and chips at the local fish and chippery all helped place us in the mindset of what living and growing up there might be like. Watching kids the same age as our main character, 14 year old Casey, running around at the local markets dragging their parents around, or loitering behind the library with their bikes. Of course, things have changed since the 70s, but the visits to the historical societies helped us out there. We learned, by chance, that the closest large town to where we were, was in fact where the largest rural hospital was at the time, and that plenty of nurses and doctors had lived in the town back then. We walked through the streets documenting houses which could have belonged to our characters, all the time fleshing them out in to the richly sculpted people they are today. Small details like whether someone needed to paint their fence, or whether someone had the champion roses of the street were all there for us to pick up on and include. Who helped them build their houses? What are the families of the characters like? Who has previously used the rusted swing set?

More recently, we did a second beach trip to a different part of the Victorian coastline, just as a location scouting expedition. Kind of surprisingly, the history we had discovered during our first trip to Inverloch was extremely different to the history of this millionaire’s playground, Sorrento, even though they’re only a few hundred kilometers apart. It was only a short trip, and we spent a lot of the time either relaxing or focusing on other parts of running our studio, but at least we were able to ask ourselves “Did sunburnt knees feel the same in the 70s?”

Jas: Putting the game in this setting, having characters and stories that are informed by our own memories and life experiences, give us a structure, a scaffolding, in which to create our story. It’s gives us tons of materials to draw from, is a universe that already makes sense, and the fact that it’s so personal to us is a big factor in us still being excited about the project two and a half years in.

As an example of one of the many benefits that have come up, on our trip to Inverloch we - actually Goldie - found this book of short stories by older folks, published in 1999 - it’s full of stories by people whose lived experience is way closer than ours to the time that our characters would have been living in.

Here’s another example of a benefit that happened just last week - our animation lead Kalonica is visiting Europe at the moment, and went to the V&A Ocean Liners exhibit in London, and she posted dozens of incredible photos for source material for our ship on Slack, spurring a ton of fascinating questions - the answers to these questions will further enrich the player’s experience.

A question we keep asking ourselves at the end of this process is, why are so many games seemingly set by default in fantasy or sci-fi settings? Of course do that if it makes sense for your game, but why not have the default be a real setting, a real time and place in history or a contemporaneous setting, and open your project up to these really exciting possibilities?

Goldie: Well thanks for listening to our experiences and some of the reasons behind why we take this stuff as an opportunity, I hope it’s given you something to think about. Along with the easy and fun and warm parts of setting a project locally, I hope the weight of some of the political stuff has been inspiring too. I’ve been in Wellington for a week and reckon it’s a bit of a haven, but I’ve just arrived here from my first international trip, ever, where I visited the Pacific Northwest of America following GDC. What I saw was sometimes beautiful, but usually darkly astonishing. The homelessness crisis and drug abuse problems are results from a long history of neglect from local and federal government, the low common wages are the result of rampant unchecked greed, and the lack of even baseline social healthcare is bewildering. Some of the tiniest towns I passed through actually desperately need those franchises I mentioned earlier to create work, as dying industries leave entire generations without jobs. In New Zealand, like just about everywhere else, there is a massive housing affordability crisis, and of course there’s the growing income inequality gap which is is a problem which both of our nations share. If a portion of people in games aren’t making work or observations about what’s happening in our homes, we’re at risk of losing what I think is a profoundly significant piece of global history AND falling behind as an introspective form of expression. Even by taking inspiration from previous interpretations of a real time or place, you enrichen the cultural value of your game, and align it with other forms of fiction in a positive and fresh way; in a way that games, I think, are ready to be aligned with.

The times we’re living in are full to the brim of injustices at the hand, primarily, of big corporations and governments willing to have their pockets lined to get power. Asylum seekers in Australia are still treated like bugs, women are still, if quietly, treated as second-best, queer people in some countries are still murdered. This stuff isn’t new, but the people in this room are young and talented, and making stuff which people want to consume. It’s important, I think, to realise that by digging in to your own local histories you can help shape cultural expectations we put upon ourselves and expect from each other. Being brave enough to call out the problems, and curious enough to explore them through interaction and narrative design even retrospectively is a meaningful way to make games. On top of this, it’s also an extremely abundant resource for entertainment, if that’s more your speed. I watched a few choice New Zealand films on my way here and we’ve seen the impact those have had on the global media landscape - why can’t games use the same lore and landscapes to create new and relevant places to play?

What you as a designer choose to take from your local histories and places is very open - which is why research is key. By dealing with real world figures or events or even whole communities or towns, remember that you have the voice to highlight things which are otherwise left in the past or brushed over.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Air COVID-19

Medical and military personnel wait at a base near Bogota for the arrival of almost two dozen Colombian migrants who were deported by US immigration officials and came home infected with the coronavirus. Photo: Aristóbulo Varón

Deportation flights seed Coronavirus in Latin America

In early March, Carlos, a 24-year-old merchant, boarded a flight from Bogota, Colombia, headed to Indianapolis and a shopping and tourism spree with his aunt. There were toys and new clothes to buy for his newborn son, his first child.

But what Carlos said was designed as a short and fun getaway instead became a nightmare stay in the United States. It ended with him spending three weeks in a Florida detention center run by the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency, before being put on a chartered passenger jet on March 30 and sent back to Colombia.

A few hours later Carlos and dozens of fellow Colombian deportees landed in Bogota, where he learned he’d become infected with the COVID-19 virus that has paralyzed the world.

The jet was one in a fleet used in a sped-up deportation program run by ICE Air Operations (IAO). The number of flights increased just as the pandemic had started spreading like wildfire across the U.S. By mid-May, more than 300 flights had arrived in 19 Latin American countries with more than 70,000 deportees during 2020, according to ICE data.

The vast majority of those deportees were not tested for COVID-19 infection before being loaded onto planes and shipped home.

On the March 30 Bogota flight, several deportees interviewed by palabra. said the passengers were chained to their seats for most of the time in the air, and no one -- not even the crew -- wore masks or gloves. The ICE flights have drawn the ire of officials in Latin America now dealing with some of the world’s highest COVID-19 infection rates, ill-prepared health systems and, in some cases, unsupportive governments.

ICE has since shifted its policy and is now testing more and more deportees, but the moves were too late for deportees like Carlos, who complain the U.S. government negligently exposed them to a lethal virus.

“I traveled with a tourist visa, but during the stop in Miami the immigration officers interrogated me for several hours and then (claimed) that my intention was asking for political asylum, which was not,” said Carlos, speaking via telephone from Bogota, where he was being quarantined. “I don't speak English, I didn’t understand what was going on, but soon after I was detained, I was wearing a blue uniform, with no access to my cell phone or a jar of vitamins I travel with for health reasons,” he said.

(Carlos asked palabra. to use only his first name. He fears stigmatization and reprisal.)

Trapped in a hot spot

Carlos was held in the Krome Detention Center in Florida -- a facility that gained national attention this spring for becoming a COVID-19 hot spot, with at least 15 detainees and staff infected.

Carlos is convinced that the stay in Krome is likely when he picked up the virus that would make him something like a “Patient Zero” -- possibly a source of infection for at least 22 others who flew with him from Alexandria, La., on the repatriation flight.

“I signed up for voluntary deportation because I wasn’t fighting for any asylum case,” Carlos said, recalling the option presented to him by ICE officials as a fast way to get back home and avoid uncertain time in detention. “I just wanted to leave that prison where I was sharing space with more than 100 people ��� . Many of them showed cold and flu symptoms and nobody did nothing.”

On April 30th, U.S. District Court Judge Marcia Cooke ordered ICE to lower the number of detainees from 1,400 to about 350 in three detention centers in Florida, including Krome. By the time Carlos was detained, seven Krome detainees and eight staff members had tested positive for COVID-19, according to court filings.

“We constantly asked the guards why there were so many people entering the prison,'' Carlos said. “By the time we were hearing news about the coronavirus, (we were worried because) even priests were being allowed in to celebrate Mass.”

Nicolas Barrera, another Colombian on the March 30 Bogota-bound ICE flight, spent four months in ICE detention, between Krome and the Wakulla County Facility in Florida. In the Krome facility, he said, there was a building with close to 100 inmates in quarantine, “but suddenly all of us were mixed, and that is where the contagion and the panic began.”

“I saw many people coughing and suffering from colds,” Barrera said. “The bunk beds were extremely close to each other.”

Barrera, holding a tourist visa, arrived in Maryland in 2004 along with his mother. When the visa expired they sought asylum; his mother retired from the Colombian Army and was escaping death threats from that country’s largest revolutionary group, the Armed Revolutionary Forces of Colombia, known by its Spanish acronym, FARC. But they missed their first asylum hearing and decided to remain, undocumented, in the city of Gaithersburg, which was a sanctuary city.

In November of 2019, Barrera fell into ICE custody after police stopped him in Florida because his car had a cracked headlight. His lawyer suggested he apply again for asylum. But the courts were closed due to the virus and in the interim he was ordered deported. “I left my wife and three kids adrift (back in Maryland). I can't believe they deported me when I was trying to reopen my case. And now this nightmare.”

Like Carlos, Barrera was asymptomatic when he arrived in Bogota.

According to Diego Molano, director of the Presidential Administrative Department in Colombia, the government believed the deportees had been tested in the U.S. So, once the deportees were in Colombia, the Red Cross took their temperatures and then the Health Secretariat conducted additional screening.

An ICE statement at the time said agency protocols for immigrants who had “final orders of removal” included “a temperature screening at the flight line, prior to boarding” and an immediate referral to a medical provider for further evaluation if any detainee presents “a temperature of 99 degrees or higher.”

Nicolás Barrera

Testing in Colombia

“Once we entered the Colombian sky, passing over San Andres (island), ICE officers took off our handcuffs and gave us masks and gloves. I didn’t receive any of those during any of my transfers (to different ICE detention centers),” said Carlos.

After landing In Colombia, the 64 passengers (56 men and eight women) on the flight from Louisiana were put into quarantine at a military base south of Bogota. They were all tested and Carlos was the one deportee to come up positive for the coronavirus.

Colombia’s Ministry of Justice initial plan was to transport all deportees on the flight to a rehabilitation center in Tenjo, a small town near Bogota. But local residents blocked the entrance to their village with stones and dump trucks. They feared being infected by the deportees.

“As I suffer from allergic rhinitis, I had a rough first night sleeping in a tent (in the military base) with air conditioning,” Carlos recalled. “By the time the results came, I didn’t have any other symptoms, but I was immediately isolated.”

A second round of tests 10 days later revealed that 22 more deportees had the coronavirus. Carlos’ account was corroborated by six of the infected migrants who spoke to palabra.

“After the first positive (test), we started to take turns eating in smaller groups,” said Karen Rivera, 32, who is a nurse by training and helped the one doctor at the military base with taking temperatures and blood samples and doing other screening of the rest of the deportees, in 100 degree weather. She was also one of three women who tested positive after landing in Colombia.

“(In the base) we spent tons of time together without washing hands properly or just using disposable masks once and again,” Rivera said, speaking via telephone from the Hotel Tequendama in Bogota, where she spent 20 days quarantined with five other deportees after their positive test results. She became seriously ill: She suffered strong headaches “like a hangover,” muscle fatigue, diarrhea, loss of taste and smell, heartburn, and even panic attacks. She said she has an underlying condition, pulmonary edema, so she was “praying every day for my life.”

Julián Mesa

No social distancing in custody

Rivera is back in Colombia after a long stay in the U.S. that began with a flight from Mexico, where she had been living. In early February she was traveling to Tampa to visit her 9-year-old daughter. But on her first stop, Miami International Airport, her luggage was segregated by U.S. Customs and Border Protection agents for a random drug test. No drugs were found, but Rivera, who had a tourist visa, was accused of trying to enter the U.S. in order to work, which her visa didn’t allow.

Rivera was sent to the Broward Transitional Center (BTC) in Pompano, Fla. Like Krome, the Broward facility was ordered by a judge to decrease the inmate population because of the coronavirus outbreak.

“I was detained in a unit facility with 120 other women,” Rivera said. “We slept six per room, shared one bathroom and didn’t have access to toilet paper or feminine products … . We used to have recreation activities three times a day, but by mid-March there was a rumor of six infections and we were locked down 24 hours a day. … I didn't have access to my anxiety medication. On top of that, the arrests never stopped; (more people arrived) and the place was overcrowded.”

Although they said conditions in quarantine at the Colombian military base were better than in ICE detention centers, deportees described having to share spaces like bathrooms and small dining tables. They slept in bunks, 14 people per tent, with the exception of the eight women, who had their own tent. In all, 64 people had access to 12 toilets and 20 shower stalls.

“The hygiene was very irregular. We had a mop, a broom and a dustbin per tent. It was our duty to clean bathrooms but there was not enough soap, much less cleaning gloves,” said Julian Mesa, 34, who spoke from his house in Donmatias, Antioquia, a small Andean town located 30 miles outside Medellín. Migration from this small town to Boston’s east side -- where Mesa was detained in September 2019 by ICE -- has been so robust that today there are 4,000 Colombians living in this corner of New England.

“Once the number of the infected (from the March 30 flight) started to increase, ambulances arrived to transport us to our respective towns, to the Tequendama Hotel or the Military Hospital in Bogota. But there was so much improvisation,” Mesa recalled. “I had to ask my municipality for protection, so I won’t have any retaliation back at home.”

Throughout Latin America, deportees who have returned home from the United States, with or without coronavirus infections, have been threatened by locals. In Guatemala, villagers told federal government officials they would lynch one former detainee if he were allowed to come home.

For Mesa, the virus first revealed itself as a mild flu and pain in his joints. The whole journey was “frightening.” Mesa spent six months in the Bristol County House of Corrections in Massachusetts while waiting for a bond appeal so he could be set free while he waited for an asylum hearing. He said he was first taken into custody in 2013, in McAllen, Texas, after escaping threats in Colombia, crossing the U.S. border illegally and claiming asylum.

“I wanted to fight (for) my asylum but by mid-March when the Colombian Embassy confirmed (it would accept) the flight back to my country, I took the chance,” Mesa said. “The conditions inside Bristol were scary. Several guards were infected, two prisoners who tested positive were isolated, but we still were sharing bunk beds with more than 60 people per housing unit. We protested. Demanded tests. But that never happened.”

On May 12, U.S. District Court Judge William Young ordered the release of dozens of ICE detainees from Bristol County correctional facilities, after a class action filed on behalf of 148 people being held on civil immigration charges.

“This facility was notorious for bad medical care, bad sanitation and very high suicide rates, so we became very concerned about what was going to happen here after the coronavirus outbreak,” said Oren Nimni, staff attorney with Lawyers for Civil Rights, a rights group representing individuals in the lawsuit.

The judge ordered tests of all detainees and staff, and a release or transfer of immigrants in Bristol. To date, 18 ICE guards and nurses have tested positive and 50 detainees have been released. “We have reports from our clients inside that testing indeed has been increased,” Nimni said, adding that detainees still complain of threats from staff that anyone asking for a test will be put in solitary confinement.

Aristóbulo Varón

Deportation: The way out

The situation in Bristol is similar to other ICE detention centers around the country where the Colombians on the March Bogota flight had been detained. Individual accounts decry a lack of social distancing, of testing and of face masks while in ICE custody and as they were moved to the pre-flight staging area in Louisiana.

Public health experts in the U.S. now say that, in optimistic scenarios, about seven of every 10 individuals in U.S. government immigration custody may become infected.

“I was detained with close to 100 people, the majority from Guatemala,” said Aristobulo Varon, 52, who was held for two months in the Port Isabel detention facility in Los Fresnos, Texas.

“When we heard the news of the number of deaths and the closure of (the U.S.) borders, we started to feel very anxious,” Varon said. “We saw some (Asian) inmates who were checked and then isolated. But it was not the case for the rest of us.”

Varon said he lived in Mexico for 20 years, and was apprehended after crossing the Rio Grande into Texas, near McAllen.

In the Port Isabel facility, Varon said he noticed that the stress of being so close to the threat of the virus was hitting some people hard, especially those who had waited years for a chance to fight their immigration cases in U.S. courts. Instead, he said, they became anxious for a chance to be evacuated.

He remembers seeing medical personnel go from bunker to bunker, talking about washing hands and keeping safe distances -- things that were impossible to do because of the crowded conditions. “Some activities like telephone calls, visits, and even the change of currency were suspended. They stopped allowing people to come inside the jail. But the uncertainty was bigger and some people discussed a hunger strike.”

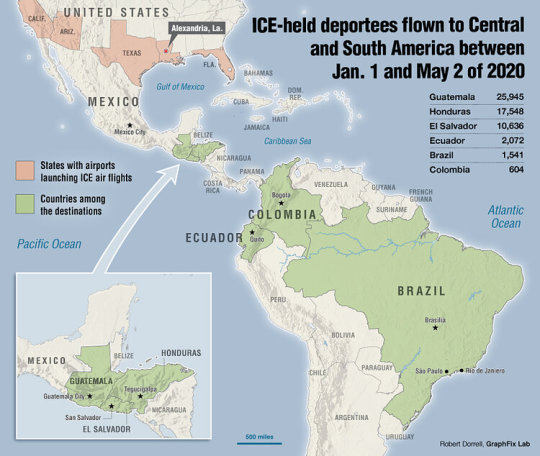

Seven Colombian inmates at Port Isabel, including Varon, were elated when they heard they were going home. What they didn’t know was that they were about to spend several days in transit -- being transferred from one center to another. ICE often moves those with deportation orders through multiple facilities, collecting more detainees and then distributing them to 13 airports across the U.S. West and South, where they’re put on planes headed for Latin America.

Jenny Guerra

Transfers without PPE

For detainees bound for Colombia, one of the points of departure is an ICE facility near Alexandria, La., where at least 14 ICE employees have tested positive for COVID-19, according to the agency.

Former detainees told palabra. that before arriving in Louisiana, their ICE planes stopped in Georgia, Texas, Indiana, New Jersey, New Hampshire and Tennessee, to pick up more deportees. At no time during their journeys, they said, did any U.S. official follow standard anti-virus protocols of wearing masks or gloves or keeping passengers at social distances.

Carlos recalled that by the time he was ready to board his flight, he was already feeling body aches and had an irritating tickle in his throat. He said ICE officers offered him salt-water gargles.

Deportees on the flight were seated together, even though several said there were many empty seats on the chartered aircraft, which could carry 135 people.

“The transfer between facilities mixing people from one state to another is concerning,” said Eunice Cho Sr., a lawyer for the American Civil Liberties Union’s National Prison Project. “Staff are not wearing PPE (personal protective equipment) and are potential vectors. Even the detainees who spent time isolated are. There is no way to prevent transmission in the planes.”

Cho co-authored an ACLU report published earlier this year. “Justice-Free Zones” investigated immigrant detention centers that had opened during the Donald Trump presidency. The report highlights conditions at detention facilities that, once the COVID-19 pandemic began, became big problems for ICE: understaffing and cost-cutting measures in medical units, lack of access to proper hygiene, unsanitary conditions in living units, and prolonged detentions without parole.

The report looked at five detention centers, including the Jackson Parish Correctional Center in Louisiana, where five detainees, interviewed by palabra., spent at least four nights before their flight home.

“This is where more people complained about the lack of soap for bathing, or cleaning supplies for their cells or bathrooms,” said the ACLU’s Cho.

Gonzalo Botero

Dodging the COVID-19 bullet

Gonzalo Botero, 76, said he was held in those conditions before boarding the March 30 flight to Bogota. The oldest on that flight, Botero suffers from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). After surviving the coronavirus, Botero said he now feels “very fortunate to be alive.”

“The most irresponsible thing (the Colombian government did) was to send me home after the positive result for COVID-19, because I then infected my wife and her nephew,” said Botero from his house in Dosquebradas, a small town in the foothills of the Andes in western Colombia. “(My wife) lost 28 pounds in 10 days.”

Yet everyone in the family survived the disease and recently celebrated Botero’s birthday.

The longtime delivery truck driver said his body is still wracked with bone pain and chills, and he often has a hard time breathing.

Before his deportation, Botero spent two weeks at the Winn Correctional Center in Louisiana. There, Botero recalled, he repeatedly asked for a voluntary deportation. He had completed a three-year prison sentence for drug trafficking and was eager to go home.

“I was freed (from prison) but spent two more months locked up, first in New Jersey and then in Louisiana, with no access to medication or doctors,” Botero said, a claim that mirrors ACLU research showing the Winn facility has had problems with inadequate medical staffing.

Understaffing was also a problem in detention centers in Texas, according to immigrants who spent time in those facilities. Jenny Guerra, 30, was detained February 26 in the Rio Grande Valley after crossing the border with the hope of working and saving money for treatment for her epilepsy, which is not covered by insurance in Colombia.

She was sent to a U.S. Customs and Border Protection holding Center in Donna, Texas, where she slept in a tent complex with 50 women. After being transferred to a nearby ICE facility, she found herself locked up with dozens of other women. She said they slept in bunk beds, shared a few shower stalls and toilets, and had no access to soap.

“If there were rumors of (coronavirus) contagion, the guards isolated the dorm, but no doctor came to check on us,” Guerra said on a phone call from her house in Medellin where she was recovering from COVID-19. “I had a throat infection, but it was not until I got to Colombia that I had access to amoxicillin and antibiotics.”

When she heard of Carlos’ infection -- she, too, was on the March 30 Bogota flight -- Guerra said she felt there was no way for her to be safe.

“I felt I took good care of myself but this virus is like a lottery. And I won it,” she said.

A doctor leaves a barracks near Bogota housing some of the Colombian deportees who returned this spring from the United States infected with the coronavirus.

A questionable coronavirus strategy

Although Colombia was the first Latin American country to run diagnostic tests in early February, its National Institute of Health has been under scrutiny for its capacity to deliver accurate and fast test results: Technical issues, broken machines and false negatives were part of Colombia’s coronavirus problem.

The institute said it wouldn't discuss confidential health records. That makes it difficult to determine if Carlos was actually the one who spread the virus on the plane. Half of the deportees on the flight have said they never received results of two different tests they took after arriving in Colombia.

As of June 30, there had been more than 95,000 reported cases and 3,200 deaths due to coronavirus in Colombia. The government extended mandatory preventive isolation until July 15, slowly opening shopping centers, hair salons and museums, while restaurants, bars and gyms remain closed.

Even though nearly half a million Colombians have been fined for violating the quarantine, according to the Ministry of Defense, Colombia has significantly fewer cases than other countries in Latin America. According to data from the Worldometer, the pandemic in Brazil has killed almost 57,000 people and the cases are rapidly rising to a million and a half contagions. Peru (282,000 cases) and Chile (279,000 cases) followed the thread in contagions but the number of deaths in those countries (9,500 and 5,600 respectively) are below the count in Mexico, where 27,000 deaths and more than 220,000 cases have been reported.

All these countries are receiving deportees from the U.S. Government. Guatemala for instance halted ICE flights after dozens of passengers were infected with COVID-19. “Our hospitals have limited capacity, but now we have to treat these patients infected with a disease that didn’t originate here,” Guatemalan President Alejandro Giammattei said during a recent interview with the Atlantic Council in Washington, D.C.

More than 300 flights

Despite all this, ICE deportation flights have continued to Central and Latin America, among other global destinations.

Witness by the Border, a nonprofit based in Brownsville, Texas, tracked 324 ICE deportation flights from Jan.1 to May 7. According to its analysis of data collected by Flight Aware, airports in Texas were the points of departure for more than half of the ICE flights. Another 17% flew from Louisiana, and 7% more from Florida. The rest departed from cities in California and Arizona. Destinations have included Barbados, Brazil, Colombia, the Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, Jamaica, Mexico and Nicaragua.

Another survey, by the Center for Economic and Policy Research (CEPR), found that between Feb. 3 and June 30, there were 366 likely ICE Air deportation flights to Latin America and Caribbean countries. CEPR adds daily updates to a database that shows departure and arrival cities, as well as dates and times.

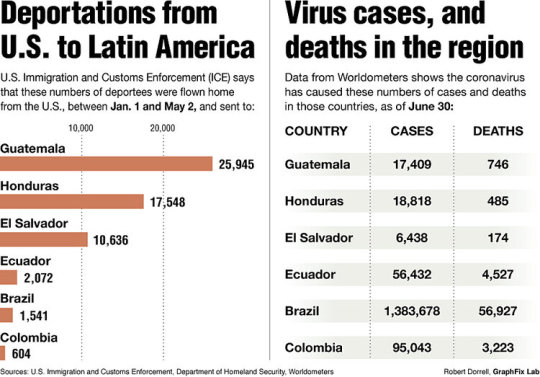

ICE officials provided data to palabra. detailing the number of deportees per country, between Jan. 1 and May 2. The report includes deportations via ICE Air, commercial flights, and a smaller number of people driven over the U.S.-Mexico border.

With 26,000, Guatemala has received the highest numbers of deportees. It’s followed by the two other countries in Central America’s Northern Triangle: Honduras, with 17,500, and El Salvador, with almost 11,000. In South America, Ecuador, with 2,000 deportees, and Brazil, with another 1,500, are suffering some of the region’s worst outbreaks of COVID-19.

According to ICE, 604 citizens were deported to Colombia between January and May 2 of this year. More have arrived since ICE changed its pre-flight protocols for detainees: All detainees on May 4 were tested before boarding a Bogota-bound plane, according to some among the 52 people on the flight. Two more groups of Colombian deportees landed in Bogota, on May 25 and June 22. There are no reports yet of infections among passengers on those flights.

ICE said the new procedures responded to orders in late April to get some 2,000 tests each month from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) “to screen aliens in its care and custody.”

“Given nationwide shortages,” an ICE spokesperson said in an email, “the agency likely won’t have enough (test kits) to test all aliens scheduled for future removals; therefore, under such a scenario, ICE would test a sample of the population and provide the respective foreign government with results.”

In a recent press release, ICE also announced that it is offering “voluntary tests” for the virus to all people held at detention facilities in Tacoma, Wash., and Aurora, Colo., and will consider doing the same at other locations.

The changes won’t hold off legal challenges by deportees on the March 30 Bogota flight. They said they are planning to sue the Colombian and U.S. governments.

Carlos, meanwhile, says he’s young and that his body was able to fight the virus.

He is now back in his home town of Antioquia, outside of Medellin. He says he has recurring dreams of a coronavirus vaccine and of never having tried to visit his aunt in Indianapolis.

As soon as he recovered, Carlos was allowed to reunite with his family. He finally met his newborn son. He went out and bought toys and clothes for him, in Colombia.

Originally published here

Want to read this piece in Spanish? Click here

#English#covidー19#ICE#Immigration#Donald Trump#Detention Centers#colombia#brazil#Guatemala#Florida#Deportations#Bogota

0 notes