#neotenic echinoderms

Photo

Transcript for the text on the image under the cut:

PAGE 1

Spectember 2020 #11 | nixillustration.com | alphynix.tumblr.com

Concept suggested by:

@sapientstarstuff

Neotenic Echinoderms

(Xenobarca materiastellarum & Atopothuria natatoria)

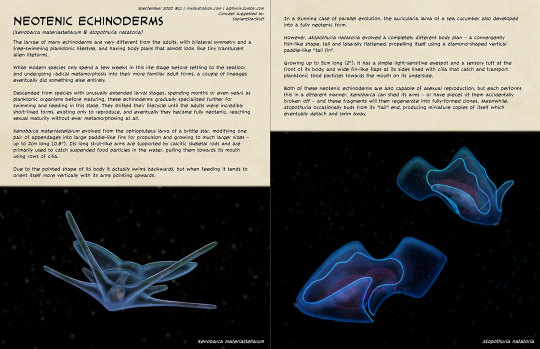

The larvae of many echinoderms are very different from the adults, with bilateral symmetry and a free-swimming planktonic lifestyle, and having body plans that almost look like tiny translucent alien lifeforms.

While modern species only spend a few weeks in this life stage before settling to the seafloor and undergoing radical metamorphosis into their more familiar adult forms, a couple of lineages eventually did something else entirely.

Descended from species with unusually extended larval stages, spending months or even years as planktonic organisms before maturing, these echinoderms gradually specialized further for swimming and feeding in this state. They shifted their lifecycle until the adults were incredibly short-lived forms, existing only to reproduce, and eventually they became fully neotenic, reaching sexual maturity without ever metamorphosing at all.

Xenobarca materiastellarum evolved from the ophiopluteus larva of a brittle star, modifying one pair of appendages into large paddle-like fins for propulsion and growing to much larger sizes – up to 2cm long (0.8"). Its long strut-like arms are supported by calcitic skeletal rods and are primarily used to catch suspended food particles in the water, pulling them towards its mouth using rows of cilia.

Due to the pointed shape of its body it actually swims backwards, but when feeding it tends to orient itself more vertically with its arms pointing upwards.

[Image: a small swimming creature descended from the larvae of brittle stars. It looks almost alien, with four long strut-like appendages extending outwards from a triangular "front" section, two shorter fins in the midsection, and two large paddle-like horizontal "tail flukes" at the rear. It's translucent, with a gut visible inside its body, and there are bands of iridescent cilia lining the edges of its appendages.]

PAGE 2

In a stunning case of parallel evolution, the auricularia larva of a sea cucumber also developed into a fully neotenic form.

However, Atopothuria natatoria evolved a completely different body plan – a convergently fish-like shape, tall and laterally flattened, propelling itself using a diamond-shaped vertical paddle-like "tail fin".

Growing up to 5cm long (2"), it has a simple light-sensitive eyespot and a sensory tuft at the front of its body, and wide fin-like flaps at its sides lined with cilia that catch and transport planktonic food particles towards the mouth on its underside.

Both of these neotenic echinoderms are also capable of asexual reproduction, but each performs this in a different manner. Xenobarca can shed its arms – or have pieces of them accidentally broken off – and these fragments will then regenerate into fully-formed clones. Meanwhile, Atopothuria occasionally buds from its "tail" end, producing miniature copies of itself which eventually detach and swim away.

[Image: a small swimming creature descended from the larvae of sea cucumbers. It looks vaguely like an alien fish, with a vertically flattened body, two fin-like flaps at its sides, and a diamond-shaped vertical tail fin. It's translucent, with a gut visible inside its body, a band of iridescent cilia loops around its body, and it has a single "eye" at the front above a small cluster of longer sensory cilia.]

#spectember 2020#spectember#speculative evolution#specevo#neotenic echinoderms#science illustration#art#not paleoart#with apologies to echinoderm experts if my understanding of the larval anatomy is wonky

193 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Late Rodentocene: 20 million years post-establishment

Riffing the Reefs: Marine Life of the Late Rodentocene

HP-02017 is easily thought of as a planet of hamsters, but other life also thrives. The ecosystem's accessory organisms released onto the planet have since formed ecosystems of their own, equally players in the game of life as the hamsters are, and nowhere is this more evident than the shallow seas of the Late Rodentocene.

At first glance, the reefs that grow in the sunlit shallows of the planet's seas look incredibly like those of our own. Forests of algae and kelp grow in the rocks close to shore, as well as corals of all shapes and sizes that sprout in great masses, forming reefs that serve as a shelter for small, colorful sea creatures that thrive in abundance. Yet despite its initial familiarity, the marine biomes of HP-02017 are anything but: its similarities are superficial, and its creatures are something else entirely.

Only a choice few organisms were seeded into the seas: small mollusks such as sea snails and bivalves, as well as sponges and corals, which at first were from but a small collection that have since diversified into a dazzling array. But with so few creatures, and so many empty niches, it didn't take long for the choice few colonists to explode into a diversity rivalling that of Earth's oceans.

Corals, which reproduced via free-swimming planktonic larvae, have filled the empty spaces of their relatives the cnidarians, with some forms becoming tentacled stinging sessile hunters akin to sea anemones, while other drifting larvae become neotenic, remaining in their mobile forms into adulthood and become the transparent, drifting mock jellies.

The humble sea snail has also seen an extreme explosion of diversity in the past 20 million years, spawning thousands of species that came to fill nearly every marine invertebrate niche imaginable. Some lost their shells, coming to resemble sea slugs, and many of which would develop bright body colors for display or as warning coloration, converging heavily on nudibranches present in Earth's oceans. Other snails, developing flattened bodies and a unique vascular system in their belly-foot, become heavily convergent on echinoderms, with some being long-bodied bottom feeders like sea cucumbers, others developing venomous spines akin to urchins, and one strange lineage, developing vaguely-arm-like protrusions on their foot and a radula adapted for feeding on bivalves, becoming a bizarre analogue of a starfish. Others become tentacled swimmers resembling shelled cephalopods: the notiluses.

But by far the most diverse and successful invertebrate clade in the planet's oceans are descendants of planktonic krill, which, in the absence of fish, exploded in diversity to fill as many aquatic niches as they can. Known as shrish, these peculiar crustaceans first emerge as shrimp-like swimmers that propelled themselves through the water with a paddling array of feathery swimming legs.

As they evolved even further, however, they began taking on peculiar niches as time went on. Bottom feeders such as the trilobug became broad and flat, filling roles akin to flatfish or crabs, and some of these bottom-dwellers secondarily re-evolved to become active swimmers, such as the filter-feeding shringray that defends itself with venomous barbs on its tail. Others became elongated, flexible centipede-like predators that hunted other shrish, lurking in caverns in coral much like moray eels in wait to ambush their prey, known as the shreels.

Some shreels would eventually develop a shorter and more streamlined body, and give rise to active swimmers that propelled themselves with undulating waves of their abdomen and tail. Becoming a more efficient means of propulsion with larger or faster species, these paddletailed shrish would eventually modify their rearmost swimming legs along with their tail fan into a caudal fluke of sorts, while their thoracic limbs became used for catching food or filtering particles from water. This lineage of paddletailed shrish would eventually bring about the biggest top predators of the Late Rodentocene seas, the shrarks. Using their barbed rostrums and spiked forelimbs as three grabbing "jaws", the shrarks reach lengths of almost a meter: rivalling the largest marine arthropods of Earth's history, the eurypterids of the Devonian era.

The reefs of the Late Rodentocene are a vast and diverse ecosystem that flourishes in strange new ways independently of the world of rodents above. Life in the ocean takes on unusual new forms in a biome not yet invaded by the hamsters -- at least for the time being.

▪▪▪▪▪▪▪▪▪

51 notes

·

View notes