#not how much you bought into christian ideas of crime and punishment while acting like the state should inflict your bizarre

Text

In relation the that true crime post I made yesterday, does anyone know good true crime YouTubers who aren't fucking weirdos about crimes, criminals, and constantly advocating for higher prison sentences acting like Americans??

If you say Princess Weeks I already follow her and if you don't it's not all true crime that just comes up go watch her shit she's very informative and let me to the In The Dark podcast, which is also very good

#winters ramblings#in americans defense obviously other countries ALSO have a USian obsession with inflicting cruelty on 'criminals'#like making them suffer A Whole Lot will result in lower recidivism rates but the US's recidivism rate is MEGA high#like i think the over all numer is some 70%?? why advocate for a system that VERY VISIBLY DOESNT WORK#especially when your ass is telling me true crime tales like i want to know how serial killing went down#not how much you bought into christian ideas of crime and punishment while acting like the state should inflict your bizarre#revenge fantasies on criminals that you have nothing to do with and if you claim thats to help victims#that doesnt help victims. you know what would?? access to mental health care and group therapy with other victims#do we do that for victims of violent crime? not that i fucking know of. seems way more helpful than throwing someone in jail for 800 years#because thats somehow supposed to solve the problem of crime and make the victim whole again#seriously id love to dig into true crime content but finding someone who isnt a fuckass is next to impossible

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Extremist #1

If you've ever really wondered how dumb I am and how much of it is an act, just watch how I completely miss the point of this series!

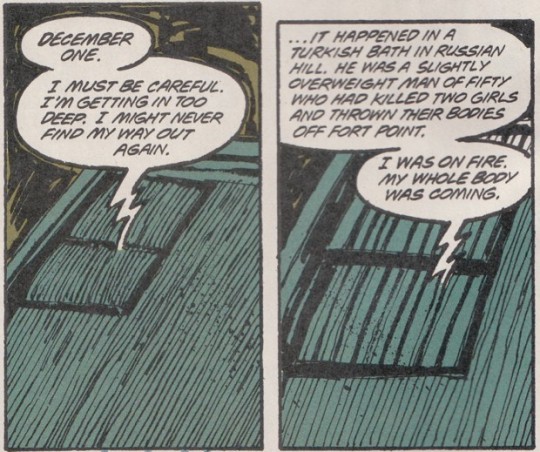

I wonder if Captain Kirk also felt like his entire body was coming every time he put on his captain's uniform?

The Extremist seems to be the one who punishes members of The Order who perpetrate terrible deeds. And somehow, the suit sexualizes the entire ordeal. So on December 1st, The Extremist punishes the slightly overweight man (who is actually obese because, I guess, Ted McKeever must be fat and he was all, "This guy, being slightly obese, should probably be drawn fatter than me!" That's just speculation. I mean, comic book writers are usually fat. The artists are usually hot fuckbots of raw sexuality) by stabbing him in his fat heart. Apparently people in The Order are allowed to engage in hedonistic pleasures that would be deemed immoral by members of the status quo. But even they have their limits on how far they allow their members to push the envelope. And Mr. Slightly Overweight killed two girls.

So what do we know so far, kids? The Extremist is The Punisher in a gimp suit who constantly gets cum stains on the inside of the leather. The Order is a secret society where people engage in illicit sexual desires. And if you murder two girls, you'll be excommunicated from The Order (meaning you'll be killed). You might be able to get away with killing one girl but that's just speculation!

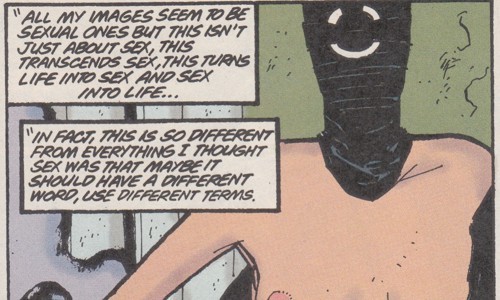

The Extremist removes the suit to reveal a woman who can't stop making sexual analogies.

Maybe it's different than what you thought sex was because sex absolutely isn't stabbing a naked fat man in the heart. Okay, maybe that's a little bit like sex.

This lady walks away from the scene of the murder thinking, "I felt like The Extremist." So was she The Extremist and she was just worried that she was enjoying filling the role too much? Or is there some other Extremist she's emulating?! This would be so much easier if it were just a connect the dots puzzle. I hope you kids at home are following along. If you're not, you're pretty fucking stupid! This story isn't even complicated yet! It's just a commentary about how life is sex and sex is life and murder is sex but maybe not life and maybe not sex but somehow you'll still come in your pants!

The Extremist mentions how she's doing this for Jack. She mentioned Jack earlier when she said something about him lying on the pavement outside a sushi restaurant while she said, "I dye my hair, Jack." So I guess the main story is about her and Jack. But it's going to be told in tiny snippets between her sex murders. Just like the real story in A Series of Unfortunate Events is the relationship between Lemony Snicket and Beatrice. I hope The Extremist gives us more of the real story per page than Lemony Snicket did. It was hard to remember all of the Beatrice details when he only mentioned her once like every hundred and twenty pages!

Later that same night, The Extremist gets a call from Patrick (who reminds her of Jack) to go out and do some more Extremist work. She wanted to give it a rest because she's worried that the suit is taking control. So I guess it's a symbiote, right? But Patrick is all, "Come right over and don't take a shower! I want you to be all sex stanky in that thing!"

The audio journal entry for that night contains the first words read in the story as a brown person's hand is seen playing one of her tapes but then rewinding it to begin the story on December 1st (as seen in the first scanned panel earlier). So that'll probably be important later!

The Extremist meets with Patrick that night, mostly because he wants to fuck her. But she consents to see him because, as The Extremist, she's looking for Jack's murderer.

She doesn't have a name yet so I can only refer to her as The Extremist. But that's a misnomer when she's out of the suit. Maybe we're not supposed to get to know her outside of the suit since this story is about The Extremist only and that is whoever is in the suit at the time.

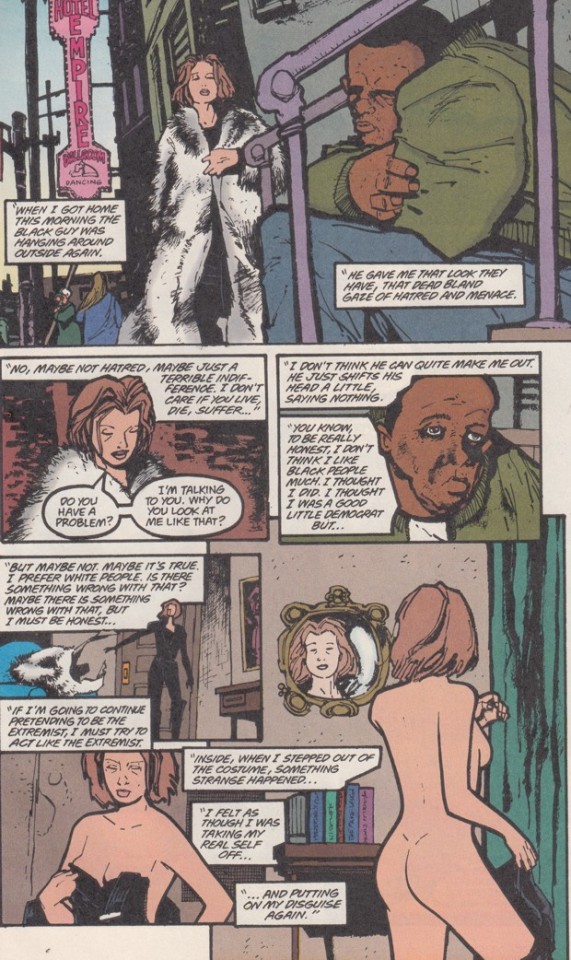

She's also racist so I guess the name fits.

Beginning a racist statement with "I'm trying to be honest" doesn't mean you have to be forgiven for your racism. Maybe begin with "I'm trying to be not racist!" Oh, and then don't add a "but"!

Patrick tells The Extremist a story about how Lords in Victorian England used to take in young East End girls living on the street. In return for giving them a home, they expected sexual favors. Patrick's ancestor stood up in the House of Lords to declare that it was the "inalienable right of every British Lord to find amusement among prepubescent working class girls." And then he says this:

In 1993, that may have seemed unlikely. In 2019, we're one speech away from Trump making this exact declaration and the GOP and evangelical Christians falling right in line behind him.

Patrick's point is that his ancestor was making, for the time, a conservative defense against liberal views that poverty stricken children shouldn't be preyed upon. His point is that the "extreme" position varies across time and space due to changing cultural mores. I think the real point is that conservative ideas are always fighting against changes that help to protect those preyed upon by the rich and powerful. Which means conservative ideas and values are always fucking wrong. I said always!

This comic book has a lot of tits and ass. But I don't think I've seen a penis yet. Not that I've been scouring every page with a magnifying glass to find one! That's slander!

When he was alive, Jack was The Extremist's husband and also The Extremist. He was cheating on The Extremist outside of The Order and his being The Extremist which I guess makes his infidelity worse. It's fine if he fucks other people in The Order or even out of The Order as long as he's currently The Extremist. But doing it out of costume and out of The Order? That's a slap in his wife's face except whatever a slap in the face is sexually. I guess sometimes it's just a slap in the face! But more often, it's probably a slap on the fanny.

Yes, I meant the British fanny!

On December 9th, Patrick kills himself in a game of American Roulette. That's Russian Roulette except instead of one gun and bullets added as you take turns, players choose from a pile of guns with one of them loaded with six bullets. I don't know if Peter Milligan just made that up but it's a pretty good joke if he did.

At the American Roulette game, The Extremist discovers Jack's killer. How she did it isn't as good as how Sherlock Holmes solves crimes. It's not even as good as how Matlock solves crimes. It's practically not even good as how Perry Mason solves crimes where he just hounds witnesses until there's just four minutes left in the hour and somebody confesses. She just notices somebody that doesn't look like they want to fuck her and just looks frightened instead and thinks, "A-ha! That's what Patrick said I should look for! Somebody who doesn't want to fuck me!" It's a good thing I don't know anybody who was murdered because I would think that every single person I ever met killed them.

The Extremist heads over to this woman's house, the woman Jack was fucking, and kills her. But first she gets her to confess! That's important because you don't want to get caught in a loop where you keep killing new people because you're unsure if you killed the murderer. That would be like a cut-rate Memento where instead of memory loss, the protagonist just suffers from mild doubt.

Judy (that's her name!) quits and moves to the suburbs. She leaves The Extremist suit and her audio tapes for somebody else to find (which somebody else does! On page one! The black homeless guy, I bet!).

Nope, she goes back for the suit because she's super horny. The black guy probably finds the suit in a later issue. Or maybe he's working for the FBI. After she retrieves the suit, Patrick contacts her. He faked his own death and has become Pierre. I guess he's a vampire or something. Is that too fantastical for a story like this? Up until now, it's been super realistic with the whole sex club for people who need extra drama and sex in their lives. Also how it takes place in San Francisco!

Patrick gives The Extremist a letter to read which is also an offer and/or her next mission. In the letter, Pierre confesses to killing Jack. The other woman was just a shill who wanted to be killed by The Extremist after being blamed for ruining The Extremist's marriage! The Extremist decides to kill Pierre because he ruined her life. The issue ends with her and Pierre about to do battle to the death. The next issue will concentrate on Jack's story, six months previous.

The Extremist #1 Rating: C-. Picture Pages! Picture Pages! Time to get your Picture Pages! Time to get your strap-ons and Rohypnol! So, kids, what did you think of our first sordid tale of sordidity? Pretend this comic book was coming out this year and I didn't know Peter Milligan was writing it. Would I purchase the next issue? Probably not. I probably only bought the second issue in 1993 because there were so many titties in this one. Porn was a lot harder to come by in 1993! Other than the titties, I'm not sure I understand the point of this story yet. Is it about what people will do when they're pushed to the extreme? How far will a mousy wife who was shocked at doing sex on top go when she finds her husband has cheated on her and he's been murdered?!

Or maybe it's about how we are the clothes we wear. Judy only loves to fuck and murder when she's in The Extremist's gimp suit. It's like that scene in Fire Walk With Me when Donna ties Laura's sweater around her waist and then starts fucking guys like crazy. Then Laura notices and is all, "Don't wear my clothes! Never wear my clothes, you dumb slut! Wait, who are you? Are you sure you're Donna? What happened to Lara?!" Sometimes I put a sock on my dick and then I'm all, "I'm a rock star! Look at me, mom!" I mean, I don't actually try to get my mom to look at me! That's just something I've heard people tend to say when they feel proud of themselves.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

1st June >> Daily Reflection on Today's First Reading (Acts of the Apostles 22:30; 23:6-11) for Roman Catholics on Thursday of the Seventh Week of Easter

Commentary on Acts of the Apostles 22:30; 23:6-11 We are now coming to the end of the Third Missionary Journey. Events are moving very fast as we have to finish the Acts in the next three days! And a great deal is happening, much of which will have to be passed over. It might be a very good idea to take up a New Testament and read the full text of the last eight chapters of the book. As we begin today’s reading let us be filled in a little on what has happened between yesterday’s reading and today’s. After bidding a tearful farewell to his fellow-Christians in Ephesus, Paul began his journey back to Palestine, making a number of brief stops on the way – Cos, Rhodes, Patara. They by-passed Cyprus and landed at Tyre in Phoenicia. They stayed there for a week, during which time the brethren begged Paul not to go on to Jerusalem. They knew there would be trouble. But there was no turning back for Paul and again there was an emotional parting on the beach. As Paul moved south, there were stops at Ptolemais where they greeted the community. Then it was on to Caesarea where Paul stayed in the house of Philip, the deacon, now called an ‘evangelist’. (Earlier we saw him do great evangelising work in Samaria and he was the one who converted the Ethiopian eunuch.) Here too there was an experience in which Paul was warned by a prophet in the community of coming suffering. Again they all begged him not to go on but he replied: “I am prepared not only to be bound but even to die in Jerusalem for the name of the Lord Jesus.” They then accepted God’s will and let him go. When they arrived in Jerusalem they received a warm welcome from the community there and went to pay a formal visit to James, the leader in the Jerusalem church. They were very happy to hear of all that Paul had done but they were also concerned (and their concern would seem to indicate that there were some in the city who had not fully accepted the non-application of Jewish law for Gentiles). The local Jews (including, it seems, the Christians) would have heard how Paul, also a Jew, had been telling Jews in Gentile territory to “abandon Moses”, that is, not requiring them to circumcise their children or observe other Jewish practices. Some suggested a tactic for Paul to assuage the feelings of these people. On behalf of four members of the Jerusalem community, he was to make the customary payment for the sacrifices offered at the termination of the Nazirite vow (cf. Numbers 6:1-24) in order to impress favourably the Jewish Christians in Jerusalem with his high regard for the Mosaic Law. Since Paul himself had once made such a vow (when he was leaving Corinth, Acts 18:18), his respect for the law would be publicly known. Paul agreed with this suggestion and did as he was asked. However, as the seven days stipulated were coming to an end, Paul was spotted by some Jews who had known him in Ephesus. A mob rushed into the temple and seized him, and might have harmed him, if the Roman commander had not seen the riot. He rescued Paul, then arrested him and put him in chains and thus out of the reach of those wanting to harm him. It was only after the arrest that the commander realised the Greek-speaking Paul was not an Egyptian rebel. Paul then asked to be allowed to address the crowd and, in a longish speech, told the assembled Jews the story of his conversion on the road to Damascus (the second time the story is told in Acts; it will be told again in chap. 26). At the end of the speech, the crowd bayed for his blood and Paul was about to be flogged in order to find out why the Jews wanted him executed. At this point, Paul revealed to the centurion that he was a Roman citizen and that, unlike the garrison commander who had bought his citizenship, he had been born one. This created great alarm among his captors and he was released. The Roman commander then ordered a meeting of the Sanhedrin to be convened so that Paul could address them. While those of the high priestly line were mainly Sadducees, the Sanhedrin also now included quite a number of Pharisees. This council was the ruling body of the Jews. Its court and decisions were respected by the Roman authorities. Their approval was needed, however, in cases of capital punishment (as happened in the case of Jesus). Paul being brought before the Sanhedrin was already foretold by Jesus to his disciples, Matt 10:17-18. Paul, in time, will appear before ‘councils’, ‘governors’ and ‘kings’. He began by telling them that everything he had done was with a perfectly clear conscience. On hearing this, the high priest Ananias ordered that Paul be struck in the mouth. It was not unlike his Master being struck on the face during his trial. Paul hit back – verbally. “God will strike you, you whitewashed wall.” He said this because, although Ananias was supposedly sitting in judgement according to the Law, he was breaking the law by striking the accused. Josephus the Jewish historian tells us that Ananias was actually assassinated in AD 66 at the beginning of the First Jewish Revolt. When Paul is accused of reviling the high priest, he said he did not realise Ananias was the high priest and apologised. It is at this point in today’s reading that one of the most dramatic scenes in the Acts, begins. Paul knew his audience and he decided at the very beginning to make a pre-emptive strike. He professed loudly and with pride that he was a Pharisee, knowing that his audience consisted of both Pharisees and Sadducees. Addressing his words specially to the Pharisees, he said that he was on trial because “our hope is in the resurrection of the dead”. That was not quite the whole story, of course, as he made no mention of Christ but it immediately put him on the side of his fellow-Pharisees. As Paul had told the Corinthians in one of his letters, if Christ was not risen from the dead, neither could we rise and there would be no basis for our faith. The hope of a future life was at the very heart of his Christian preaching. That, of course, is not what the Pharisees heard. They immediately latched on to the fact that Paul, as a fellow-Pharisee held a belief that was denied by the Sadducees. The Sadducees only accepted as divine revelation the first five books of the Bible, what we call the Pentateuch. The resurrection of the body (in 2 Maccabees) and the doctrine of angels (in the book of Tobit) did not become part of Jewish teaching until a comparatively late date. On both these issues, however, Paul (a Pharisee himself) and the Pharisees were full agreement In the first five books of the Old Testament, there is no mention of a future resurrection, nor spirits, nor angels. It was on the basis of this belief that the Sadducees had challenged Jesus about the fate of a woman who had married seven brothers. If there is a resurrection, which of the seven would be her husband? For those who did not believe in life after death, the question was a nonsense. Paul’s words on resurrection immediately diverted attention from him to this contentious dividing point between the Pharisees and the Sadducees. All of a sudden the Pharisees make an about-turn: “We do not find this man guilty of any crime.” And, in a deliberate provocation to the Sadducees who did not believe in angels: “If a spirit or an angel has spoken to him…” This could be a reference to Paul’s account to them earlier of his experience on the road to Damascus. All objectivity was forgotten and the Pharisees, despite their earlier protestations, sided with Paul, “their man”, and a brawl ensued. It got so serious – and, remember, these were all “religious” men! – that the tribune, fearing Paul would be torn to pieces, came to his rescue and put him back in the fortress. That night Paul received a vision in which he was assured that he would be protected in Jerusalem because it was the Lord’s wish that he give witness to the Gospel in Rome. Perhaps Paul’s behaviour in this situation is a good example of Jesus” advice to his disciples to be simple as doves and as wise as serpents! Paul was more than ready to suffer for his Lord but he was no pushover. While we, too, are to be prepared to give witness to our faith even with the sacrifice of our lives, and never to indulge in any form of violence against those who attack us, we are not asked to go out of our way to invite persecution or physical attacks. That is not the meaning of the injunction to carry our cross. Jesus himself often took steps to avoid trouble. Joan of Arc defended herself as did Thomas More and, indeed as Jesus himself did during his trial: “If I have said something wrong, why do you strike me?” But, like them, we will try never to evade death or any other form of hostility by compromising the central teaching of our faith.

1 note

·

View note

Text

17th September >> Sunday Homilies and Reflections for Roman Catholics on The Twenty-Fourth Sunday In Ordinary Time, Cycle A

Gospel reading: Matthew 18:21-35

vs.21 Peter went up to Jesus and said: “Lord, how often must I forgive my brother if he wrongs me? As often as seven times?”

vs.22 Jesus answered, “Not seven, I tell you, but seventy-seven times.

vs.23 And so the kingdom of heaven may be compared to a king who decided to settle his accounts with his servants.

vs.24 When the reckoning began, they brought him a man who owed ten thousand talents;

vs.25 but he had no means of paying, so his master gave orders that he should be sold, together with his wife and children and all his possessions, to meet the debt.

vs.26 At this, the servant threw himself down at his master’s feet. ‘Give me time’ he said, ‘and I will pay the whole sum.’

vs.27 And the servant’s master felt so sorry for him that he let him go and canceled the debt.

vs.28 Now as this servant went out, he happened to meet a fellow servant who owed him one hundred denarii; and he seized him by the throat and began to throttle him. ‘Pay what you owe me’ he said.

vs.29 His fellow servant fell at his feet and implored him, saying, ‘Give me time and I will pay you.’

vs.30 But the other would not agree; on the contrary, he had him thrown into prison till he should pay the debt.

vs.31 His fellow servants were deeply distressed when they saw what had happened, and they went to their master and reported the whole affair to him.

vs.32 Then the master sent for him. ‘You wicked servant,’ he said. ‘I canceled all that debt of yours when you appealed to me.

vs.33 Were you not bound, then, to have pity on your fellow servant just as I had pity on you?’

vs.34 And in his anger the master handed him over to the torturers till he should pay all his debt.

vs.35 And that is how my heavenly Father will deal with you unless you each forgive your brother from your heart.”

*******************************************************************

We have four sets of homily notes to choose from. Please scroll down the page for the desired one.

Michel DeVerteuil : A Trinidadian Holy Ghost Priest, Specialist in Lectio Divina

Thomas O’Loughlin: Professor of Historical Theology, University of Wales. Lampeter.

John Littleton: Cashel Diocese, Director of the Priory Institute Distant Learning, Tallaght, Dublin

Donal Neary SJ: Editor of The Sacred Heart Messenger

****************************************

Michel DeVerteuil

Lectio Divina with the Sunday Gospels- Year A

www.columba.ie

General Comments

Today’s passage deals with the crucial issue of forgiveness, surely the most pressing of all our human problems, as individuals, as communities and as a human family. The future of humanity is in the hands of those who can forgive.

It is important to understand Peter’s question correctly: it is not about being wronged many times (a situation which Jesus speaks about in Luke 17:4). Here, Peter is asking about one wrong. We are dealing then with a very deep hurt, the kind that remains with us for years and that we find ourselves having to forgive many times over. We think we have forgiven, but when we meet the person who hurt us we realise that we have to start forgiving all over again. This is the question then – how long do we continue with this struggle to forgive the one wrong?

We must think not merely of personal wrongs but of deep ethnic and racial wrongs, the kind that have nations torn by civil strife for generations – the human family knows so many of these at present.

As always, Jesus does not give us prescriptions; he invites us to enter into the God-like way of seeing things and leaves it to us to decide how we will act out of that consciousness.

Jesus’ response is in the form of a parable, and the key to interpreting his message correctly is to

understand how a parable is meant to be read. We are accustomed to learning (and teaching) through

“edifying stories.” In this kind of story the characters are either “good” or “bad”; we are meant to imitate the good ones and avoid being like the bad. It is always wrong to read a parable like that. We find that we identify one of the characters with God and end up with a strange God, one who tortures those who don’t forgive their enemies, burns the cities of those who do not accept his wedding invitation, closes the door on the bridesmaids who come late for the wedding feast, and so forth. Many Christians have developed warped ideas of God as a result of reading Jesus’ parables in this way.

A parable is an imaginative story which we enter with our feelings. We identify with the various characters as the story unfolds, until at a certain point it strikes us: “I know that feeling!” This is a

moment of truth, when we say, “I now understand grace and celebrate the times when I or others have lived it,” or “I now understand sin and experience a call to conversion.”

In this parable we see a man who is in a position of total helplessness; he is made to feel worthless, he has neither dignity nor freedom. His life, and that of his entire family, is in the hands of this king who makes him grovel before he will condescendingly set him free of his debts. He is not a bad man: he has been generous enough to lend money to someone who is in even greater need than he is, knowing full well that sooner or later he will have to return his own loan to the king.

The problem with him is that his spirit has been broken by oppression. Hardship has extinguished the spark of generosity. Experience tells us how frequently this happens. He has been made to feel so helpless and impotent that when he finds someone with even less power than himself he oppresses him in turn.

The king also is a victim of oppression. He breaks out of the oppressive world when he forgives his servant (even though we can detect some condescension), but it doesn’t last. The servant’s meanness defeats him, he takes back his generous spirit and becomes as mean as the servant. Very different from our God!

The parable then makes us reflect on oppression, understood quite correctly as being indebted. What a terrible thing oppression is! It keeps everyone in bondage – the oppressed and the oppressors alike. It isn’t God who keeps us in bondage, but we ourselves, and the parable tells us that we will continue in this bondage, “handed over to torturers”, unless someone makes a breakthrough and replaces meanness with generosity of spirit, the spirit of forgiveness, permanent and unconditional, “from our hearts.”

We can reflect on the movement of oppression/forgiveness at different levels – on the world stage, in our countries, within our families and neighborhoods, in our own hearts. In each case, we celebrate the people who have made the breakthrough.

In our own hearts: what unforgiven hurts still “torture” us? We recognise the bitterness which keeps us in bondage, consuming our energies, preventing us from enjoying life and being at peace with those around us. We remember the times when we were able to free ourselves, even if only temporarily, like the king.

Within families and communities: so often we are concerned mainly about punishing the offender. We celebrate today the peacemakers among us, those who work through mediation to re-establish harmony within the community.

Within nations, especially between ethnic groups, social classes, religions. We think of Northern Ireland, former Yugoslavia, the Republic of Congo, Sri Lanka, India and Pakistan, the black community in the United States – the list can go on and on!

We think of the debt of the third world countries, causing anger, resentment and civil strife. Indifference to the plight of those who are in debt keeps the whole human family in bondage.

Prayer Reflection

As we begin our prayer, let us listen to some of the prophetic voices of our time speaking of forgiveness to our modern world which is so much in need of it:

“The philosophy of retributive justice has brought nothing but chaos and widespread distress to families caught up in it. It has guaranteed a growing level of crime and has wasted millions of taxpayers’ money. We need to discover a philosophy that moves from punishment to reconciliation, from vengeance against offenders to healing for victims, from alienation to integration, from negativity and destructiveness to healing and forgiveness. Retributive justice always asks first: how do we punish the offender? Restorative justice asks: how do we restore the well-being of the victim, the community and the offender?” …. Vincent Travers, o.p. in Religious Life Review, Sept./Oct. 1995

“The experience of forgiveness leads us to a radical understanding of the doctrine of Grace. We are saved, not by getting it right, but by the love that redeems us while we are getting it wrong.“…

Richard Holloway, Dancing on the Edge

– “There will come a day when the martyr will be made to stand before the throne of God in defense of his persecutors and say, ‘Lord, I have forgiven in thy name and by thy example. Thou hast no claim against them any more.'”…A Russian Orthodox bishop wrote these words as he went to his death in one of Stalin’s purges

“O Lord, remember not only the men and women of good will, but also those of ill-will. But do not remember all the suffering they have inflicted on us; remember the fruits we have bought thanks to this suffering – our comradeship, our loyalty, our humility, our courage, our generosity, the greatness of heart which has grown out of all this. And when they come to the judgment, let all the fruits that we have borne be for their forgiveness.”

Prayer found in the clothing on the body of a dead child at Ravensbruck camp where 92,000 women and children died; in Mary Craig, “Take up your Cross,” The Way, Jan. 1973

“While waiting for the Kingdom, make the Kingdom. While waiting for righteousness and peace, practice righteousness and peace. You want a paradise of love? Forgive.” …..Carlo Carretto, Summoned by Love

Lord, we ask you to look with compassion on the many people in our world who are held in bondage because they cannot forgive from their hearts.

What they have suffered may seem trivial to us, a mere one hundred denarii, but they are handed over to torture

until they have paid their debt of forgiveness.

Pope Francis visiting the church of Santa Maria in Trastevere during a visit to the Sant’Egidio community in Rome

We thank you for the great people of our time who, like Jesus, work for the forgiveness of debts

– John Dear and the Fellowship of Reconciliation in Washington, D.C.;

– the Sant Egidio Community in Rome;

– the Tallaght Community Mediation Scheme in Dublin;

– Archbishop Tutu and the Truth Tribunal in South Africa.

We thank you that these servants, following the way of Jesus,

are showing our contemporaries that unless they forgive from their hearts

you have no choice but to leave them and their communities in bondage.

We thank you for those who have taught our world forgiveness:

– spouses who welcomed back those who had been unfaithful;

– members of minority groups who work for racial harmony in their neighborhoods;

– devotees of traditional African religions in dialogue with the mainline churches;

– Nelson Mandela;

– Pope John Paul II and Pope Francis.

We thank you that, unlike the king in Jesus’ parable,

they did not let themselves be turned aside from the path of forgiveness,

but forgave seventy-seven times.

Lord, have pity on the many countries that are being torn apart by traditional hatreds;

send them men and women who will show their compatriots

that unless they forgive from their hearts

they will be forever tortured by hatred and the desire for revenge.

*********************************************************

Thomas O’Loughlin

Liturgical Resources for the Year of Matthew

www.columba.ie

Introduction to the Celebration

We often describe ourselves as ‘the People of God’ and as ‘a people set apart’; and very often such names have been misinterpreted by Christians to mean that we are somehow ‘God’s elite’ or that he has some special friendship for us and our doing that he does not show to others. Today’s gospel confronts us with the reality of what it means to be ‘a people set apart’. We are the ones who must reject the desires for vengeance and retaliation, and in the face of those who offend us must work for reconciliation. To start afresh, working for what is good, after one has been hurt is never easy; it goes against a deeply embedded instinct in our humanity that calls for retribution. But to be the group who seek to continue the reconciliation of the world that was accomplished in the Paschal Mystery of Jesus is what we are about. Now, as we begin to celebrate this mystery, let us remind ourselves that as ‘a people set apart’ we must be willing to be those who bring forgiveness and new hope into the world. Let us ask ourselves whether we are willing to be reconcilers.

Homily notes

1. Reconciliation is a word that is bandied about in Christian discourse: we talk about it in relation to individual sinfulness; we talk about it in social situations of injustice; and we use it as the name of one of the sacraments: the Sacrament of Reconciliation. We use the word so often that it can become just a synonym for repentance, penance, the process of ‘getting rid of sin’, offering forgiveness, or a process for rebuilding harmony in society. It is all of these things, but it is also one of the key words by which we can understand

(1) the role of the Christ in relation to church,

(2) the role of the Christian body towards the larger society, and

(3) the one of the central Christian attitudes towards life and how it should be lived.

This sculpture is called ‘Reconciliation’. It is in the ruins of the old Coventry Cathedral in England

2. It is easiest to begin by sketching the habit of being reconciliatory, being someone with the attitude of wanting reconciliation. It is worth noting the exact implications of Peter’s question of Jesus: ‘Lord, how often shall my brother sin against me, and I forgive him? As many as seven times?’ There is no hint in the text that this brother has come and asked for forgiveness. This is not a mutual process. The forgiveness in question is a unilateral act by the one who has been sinned against. Someone has been offended/ attacked; that person now wants to forgive the offender without any hint of the offender seeking forgiveness or showing an awareness of their crime or showing contrition. The question is how often is this attitude of offering forgiveness unilaterally and unconditionally to last? Is it a one-off event, something that should be given a good trial (let’s say ‘seven times’) or something that must be on-going (‘seventy-times seven’)? The Christian position is made abundantly clear.

But what is this attitude? The forgiveness in question consists in continuing to seek the way that builds up peace with those who offend one, rather than seeking either to get revenge for their offences or seeking to write them out of the script of one’s own plans for right acting. The Christian must act rightly, despite how others behave, even when that behaviour is directed against them. Reconciliation is the steady willingness to build the universe aright in spite of, and in the aftermath of, those who would break down peace and goodness between people, or between people and the environment. One must not only seek to stop damage to individuals, society, the environment, but one must always be ready to start over, repair damage, and begin again. This beginning afresh, rather than pursuing a vendetta or engaging in recriminations, is at the heart of reconciliation.

3. The task of the Christian body, the church, is to act as an agent for reconciliation in a human situation where, after any offence has been felt, our instincts and’ gut reaction’ is to find the culprit, extract redress (sometimes we are honest and openly call this ‘vengeance’ and admit that we like the idea of ‘getting our own back’; sometimes we opt for spin and speak of ‘restoring the status quo’ or of ‘condign justice’), and then have an extended period during which the offender suffers the effects of their crime whether this is imprisonment, isolation, being given the cold shoulder, or some other kind of exclusion. However, reconciliation is focused not upon redress, but upon getting back on track, repairing the damage, and starting afresh. The past is past; we must get on with building the kingdom of justice, love, and peace. If we look back it is only to learn lessons, not to engage in the activity of retribution. This is a very different view of the way humans should act to that which most societies have pursued either now or in the past.

The church is the minister of reconciliation whose vocation it is to work to repair the damage done within the creation, material and human, from evil choices. And this ministry cannot be confused with wagging fingers at problems nor naming sins, nor should it be reduced to the individual reconciliation of penitents, (viewed in terms of an individual’s relationship with God). This working for reconciliation is part of the priesthood of the whole people of God.

Wherever there is division, corruption, suffering or disruption in the order of things, there is a task of reconciliation to be addressed; and Christians make the claim that they are willing to adopt this task as their own. In a world where the pursuit of vengeance keeps conflicts running and multiplies the amount of suffering and misery, Christians are supposed to be taking a different tack.

4. Reconciliation is also a way of understanding the Christevent: God in Jesus was reconciling the world to himself. The pattern for all Christian reconciliation is the way the Father has offered a new beginning to the creation in the Last Adam. This use of reconciliation as an overarching theme for the whole of the gospel is captured in the opening statement of the current formula of sacramental absolution: ‘God, the Father of mercies, through the death and resurrection of his Son has reconciled the world to himself and sent the Holy Spirit among us for the forgiveness of sins. The Father allows us to begin afresh and to then grow to the fullness of life; we rejoice in this as the joy of faith. We must allow those who have harmed us/ our creation to start afresh and help

them grow to the fullness of life; we accept this as the challenge of the life of faith.

5. Perhaps we are now in a better position to appreciate the wisdom of Ben Sira: the homily could conclude by reading the first reading again as its various messages (e.g. ‘stop hating’) should now fit into a larger framework.

****************************************************************

John Litteton

Journeying through the Year of Matthew

www.Columba.ie

Gospel Reflection

Why was Jesus so insistent about the practice of forgiveness in the lives of his disciples? Peter was probably embarrassed by Jesus’ answer to his question ‘How often must I forgive?’ Jesus told Peter to be far more forgiving than he was suggesting. Peter must forgive seventy-seven times, not seven times.

In saying this, Jesus was not implying that forgiveness could be refused on the seventy-eighth and subsequent occasions. For Jesus, there could be no limit to the number of times people would forgive. Forgiveness was to be a continuous activity and one of the central characteristics of the Christian lifestyle.

So why was Jesus so adamant that his listeners would understand how his message of forgiveness was central to his teaching and preaching? Was it because he wanted to be excessively demanding? Or was it because he knew that forgiveness was among the most difficult challenges for human beings?

Orthodox priests pray as they stand between pro-EU protesters and police lines in central Kyiv, Jan. 24, 2014.

It would have been easier for most of Jesus’ disciples to be unforgiving because they had direct experience of oppression and injustice from the Romans, who were occupying their country, and from the tax collectors, moneylenders and religiow leaders. Did Jesus want to raise the standards and expectatiom beyond their capabilities? The answer to these questions is ar emphatic ‘No’.

Jesus was uncompromising about the centrality of forgiveness because he understood human nature completely. He knew that if people would not forgive one another, and if they could not graciously accept forgiveness from other people when it was offered, then they would be unable to experience God’s forgiveness. Jesus appreciated that the human spirit yearns for acceptance, sympathy, respect, companionship and a sense of belonging. None of these is possible in the absence of forgiveness.

Practising forgiveness, therefore, enables us to realise these yearnings. Our greatest gift from God — the ability to love — is dependent on our ability to forgive. Forgiveness brings healing. If there is no forgiveness in our lives, then our human nature becomes flawed. We feel isolated. We become less than human and, eventually, our dignity and sense of self-worth diminish. Our innate beauty derived from being made in the image and likeness of God is shattered. There is a diminution of the quality of human life and living.

Jesus always forgave

When, as repentant people, we celebrate the sacrament of reconciliation properly (that is, we confess our sins, make reparation for our wrongdoing and resolve not to commit these sins again) we are assured that our sins are forgiven and that we will have God’s help to avoid sin in the future. We all need to experience forgiveness in our lives. The sacrament of reconciliation enables us to receive God’s forgiveness for our sins. We become whole human beings again, capable of tremendous love and sacrifice. Is it any wonder, then, that Jesus insisted on forgiveness among his followers?

For meditation

And in his anger the master handed him over to the torturers till he should pay all his debt. And that is how my heavenly Father will deal with you unless you each forgive your brother from your heart. (Mt 18:34-35)

*************************************************************

Fr Donal Neary, S.J

Gospel Reflections for the Year of Matthew

www.messenger.ie

Forgiveness

We are called to forgive; and that can be really difficult. You have been defrauded by the banks of your life’s savings – can you forgive? You were abused as a child – can you forgive? You were done out of a job because another lied to get it – can you forgive? The answer is maybe ‘no’. What then does God want? He asks us to open our hearts to the other so that we may forgive. Forgiveness is the deepest of God’s desires on our behalf, and he hopes that we can forgive each other.

Our hurts and burdens are heavy to carry through life. To forgive can release some of that weight. The person who hurt us may be dead, or may not even know (or care) that we are hurting. When we desire to forgive but don’t know how, one way of looking for this strength is to pray for it. We often pray, ‘Lord, make my heart like yours’. When we pray that we are praying to be forgiving people!

Another way is to pray for the person. When we realise that as God loves me, he also loves everyone, we may find a spark or light of forgiveness in our souls.

Out of this we may find the will to meet the other and talk to him or her, and find the grace of forgiveness between us.

Forgiveness sometimes comes slowly. When God sees us wanting to be on the road to forgiveness, he gives us the graces we need to unburden ourselves and be able to love like him.

Sit in silence for a while, and send a blessing or prayer

to someone you need to forgive.

Lord, I ask – make my heart like yours.

********************************

0 notes