#not shown in the drawing is Olivier being very normal about this

Text

world famous gun show and im at front row

@hellofromthehallowoods

#i draw her a healthy amount of times promise#/lying#I MISS HERRR#not shown in the drawing is Olivier being very normal about this#riot maidstone#hfth#hello from the hallowoods

84 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pachycephalosaur domes: Anatomy

Pachycephalosaurs were a group of ornithischian dinosaurs known exclusively from the Upper Cretaceous of the northern continents, best known for the distinctively domed skulls found in the adults of many species. Despite being among the most popular dinosaurs to be portrayed in media, the origins of the clade is shrouded in mystery, owing in part to a trend of poor preservation within the clade, especially regarding bones other than those of the skull. A ghost lineage of over 60 million years separates the earliest members of their sister clade, Ceratopsia, from the earliest known definite pachycephalosaur fossils (Xu et al., 2006). Also a source of debate has been the function of their frontoparietal domes, with proposed functions ranging from an anti-predator weapon to display to being simply the support structure for a much larger keratinous horn. In this series we’ll be taking a journey through the pachycephalosaur dome and different interpretations of it throughout history. Let’s start with the anatomy of the dome!

(Image: a 3D-printed skull of Stegoceras, a representative pachycephalosaur. Different bones are represented in different colours; the frontoparietal dome is the large blue bone on top of the head. Photo by me; scans for bones were provided by Jann Nassif and Larry Witmer)

The pachycephalosaur skull is notable for the extreme level of fusion present between the various cranial elements, making much of the skull seem almost like it’s made of one continuous bone. In particular, an extreme level of fusion occurs between the frontal and parietal elements, and they are referred to collectively as the frontoparietal (Gilmore, 1924).

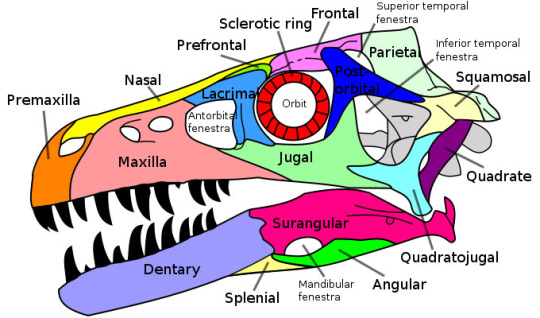

(Image: A drawing of the skull of Dromaeosaurus, a theropod dinosaur. This image is here to serve as a more “normal” dinosaur skull in comparison to the modified pachycephalosaur skull. The frontal and parietal (above and behind the eye) are unfused! Image from [source]).

In most or all known genera, these bones are dorsally expanded and greatly thickened, forming a dome of solid bone that can reach up to 222 millimetres (8.75 inches) in thickness in the largest species (Sues, 1978)! [It is worth noting, however, that some specimens lack domed skulls, instead being flat-headed. Interpretations of these forms has been problematic and will be discussed in a future post, which will be linked here when it’s up.]

Because the dome is so thick, it’s able to survive damage that would destroy the rest of the body after death. ,Therefore many species of pachycephalosaur are known exclusively from the frontoparietal dome.

(Image: six different pachycephalosaur frontoparietal domes. Some of them are pretty badly eroded, but all are recognisable. Image from Peterson et al., 2013)

Pachycephalosaurs have been long known from the North American fossil record, though interpretation of their biology was long clouded by poor fossil remains. Joseph Leidy — who you should really read about - he did a lot of neat things! He also named some indeterminate tooth taxa that have shown up here before. —Joseph Leidy in 1872 described a partial squamosal as Tylosteus ornatus, though he did not recognise that it was a dinosaur and instead considered it to be indeterminate skin armour of a reptile or armadillo-like mammal (Baird, 1979).

The first pachycephalosaur to be recognised for its cranial dome was Stegoceras, though the only remains discovered were two domes and the taxon’s affinities were long contested. Lambe (1902) recognised the dome as a midline skull bone from a dinosaur; however, with no more complete specimens to draw on, he identified it as the nose horn of a Triceratops-like animal. Baron Nopcsa in 1903 was the first to identify the element as being formed in part by the frontal, though he mistakenly considered it to be a fusion of the frontal and the nasal, and considered it to have been a “unicorn dinosaur”, related to either ceratopsians or stegosaurids.

Hatcher (1907) believed that the domes did not belong to a ceratopsian or even to an ornithischian, but to “some other reptilian order”. Hatcher did however, correctly identify the domes as being formed from a fusion of the frontals and parietal (though he erroneously also included the occipital), and opined that the structure did not support a horn, but rather functioned to strengthen the skull roof. Several years later, Lambe (1918) described a partial posterior skull of Stegoceras which confirmed the identification of the domed element; Lambe created the new grouping Psalosauridae to contain the genus and considered it to be closely related to ankylosaurs and stegosaurs, but made scant comment on the function of the dome beyond armouring the brain (presumably against attacks from predators).

It was not until the 1920s that a more complete specimen of Stegoceras was described, leading to a better understanding of the anatomy of the clade (Gilmore, 1924). Based on the very un-thyreophoran-like body fossils, Gilmore assigned Stegoceras to Ornithopoda; however, due to their very similar teeth, he also placed it within Troodontidae.

This, incidentally created a confusion that lasted for over twenty years, in which pachycephalosaurs were confused with troodontids - two groups very distantly related. Pachycephalosaurs, of course, were ornithischian dinosaurs closely related to ceratopsians like Triceratops, while troodontids were a group of extremely bird-like theropods.

(Image: a meme in which the first panel shows two cards, with a troodontid and a pachycephalosaurid on them, with text saying “Corporate needs you to find the differences between this picture and this picture. The second panel contains an image of Charles Gilmore saying “They’re the same picture.” Art by @thewoodparable and @palaeoshley)

Gilmore also was the first to note that juvenile pachycephalosaur specimens, which he identified by their smaller size and lower degree of bone fusion, had much lower domes than did adults, though he did not elaborate on the biological implications of this. Further, Gilmore noted that the occipital condyle - the part of the skull that connects to the neck - was rotated downwards. This is really unusual; in almost all other animals the neck attaches to the back of the skull. (The only exceptions I know of are humans and woodcocks.)

(Image: An American Woodcock. Image by Mark Olivier, from Macaulay Library.)

From this, Gilmore concluded that the animal usually held its head with its nose downward. Gilmore was also the first to propose that pachycephalosaurs preferred upland habitats, and suggested that this may explain the scarcity of postcranial remains.

This series will continue with a look into ideas proposed into what exactly pachycephalosaurs were doing with their domes. Part II can be found here, and part III can be found here!

309 notes

·

View notes

Text

Is This How I See Jaime?

Objectively speaking, I am not that old. Still there’s no getting past the fact that I am getting older every day, like everybody else. I might not be at the point where my body betrays my age, where I ache all the time and grunt when I stand, but my mind still carries with it the weight of decades of lived experience, and this can at any moment make me want to lie down.

There are few artists that capture the feeling of aging quite like Jaime Hernandez. Partly this is because of his working method. No one else does what he does, making serialized comics for close to forty years, that tell stories with the same characters. These are not truly STORIES, utilizing flashbacks that provide crucial context to events and create literary effects, even as the overall narrative they tell moves forward in time and builds an attachment between reader and character comparable to long-running television series. Still, when broken up into serialized installments in issues of Love And Rockets, it can frequently feel like nothing is happening. Often, what you get in an individual issue is around fifteen pages, split between multiple pieces focused on different characters. These fragments are focused, compressed in a manner closer to cinema than television, but you’re still only getting what might amount to three to five minutes depicted on-screen. With a few exceptions, what you get in an issue is not a complete short story with a beginning, middle, and end. For all the influence the Hernandez Brothers have had on alternative comics, reading the people they’ve influenced will not prepare you for how much Love And Rockets is modeled off of serialized comics, and how much of its power it draws from continuity and extended engagement.

This pacing demands a certain level of expectation-free interaction, which is crucial to deep relationships. It’s worth noting Jaime’s strips run alongside his brother Gilbert’s work, which is similar in some ways, but by no means the same. Gilbert’s body of work is a lot more complicated, due in part to how prolific he is, the meta/self-referential/self-deconstructive elements of the stories he’s telling, and also how he draws tits like Mark Newgarden draws noses, that just keep getting larger. He deserves a deep critical reading, but I don’t have the energy, money, or time to keep up with him. Running the two brothers’ work side by side makes Love And Rockets implicitly about family, which then in turn becomes a subject each cartoonist explicitly makes work about. And not just “chosen” family, but the actual people who’ve known you your entire life. Which is, inherently, a concept which both means more the older you get, and remains somewhat alienating. As a reader, it helps to be prepared to extend to Love And Rockets the goodwill one would a family member, to begin to get on its level.

On a superficial level, making work about family seems somewhat conservative and nostalgic. That’s not to suggest it’s not valuable, or worth fighting for. There’s just a certain adjustment of values or attitudes a reader needs to make to get on board with the work, that might be at odds with the punk rock alternative comics reputation that precedes it. The comics themselves are built on a formal language of cartooning that’s older and out of fashion: Sixties Ditko comics, Lil Archie, Dennis The Menace Goes To Mexico. This adds to a feeling of being about aging in a way younger art cartoonists inspired by their same-age immediate peers can’t get to. For instance, I love Olivier Schrauwen, and I can see the influence Yuichi Yokoyama has on his work, and I view the two of them as peers in dialogue, creating the future of comics, which creates a totally different reading experience than I get reading work that feels more in dialogue with the past. The formal choices of the Hernandez brothers, including that their work appears for the first time in serialized comic book formats, calls conscious attention to history. Consciousness of the past hurts, and this truth is a huge element of the plots and themes of Jaime’s work.

It’s the sheer graphic strength of Jaime’s drawing that enables it to stick in the memory. He’s able to capture a tiny gesture and render it iconic through use of line and spotted blacks. The precision he brings his images gives them a certain ease of recall. This is the crux of a two-page spread at the climax of The Love Bunglers where, as a bunch of different stories and images are recalled, now rendered at different angles, they’re all there in your consciousness, in a mix of your memories of the comic and your memories of your own individual life. It’s a hugely cathartic climax.

However, both Gilbert and Jaime have this aspect to what they do that can easily frustrate a reader, and it is seemingly inextricable from the core of their power: Once a point is reached where you can easily follow along, and a satisfying conclusion to a story occurs, the next several issues will completely destabilize that and you will again not know what exactly is going on. For instance, if you read the Perla La Loca collection, collecting the “Wigwam Bam” and “Chester Square” graphic novels, by the end of it, you will have a very exciting experience that should convince you Jaime Hernandez is one of the greatest cartoonists in the world. Reading the Penny Century collection of the work that followed, plenty of stories will leave you feeling like he lost his touch, or is spinning his wheels. At the end of the book, and the “Everybody Loves Me Baby” story, you’re knocked flat on your ass again, but if you had read the original comic books as they came out, who knows if you would’ve stuck it out that long.

This, by the way, is one of the most realistic things there is. Life’s “things just keep happening” quality will fuck you up time and again. While I haven’t given up on life just yet, I have stopped reading Love And Rockets a few times. I’m not the sort of reader who sticks with a series out of inertia. I have always been hyper-aware of the value of my comic-book buying dollar, and therefore pretty fickle. If I read two issues straight of a comic that feels like it’s treading water, I would be done with it. I’ve gone back and picked up things after the fact and filled in gaps, or I’ve switched to reading trade collections checked out from the library. I bought the first two issues of the recently relaunched Love And Rockets volume 4 in one go, realized that it was continuing stories from Love And Rockets: New Stories, and didn’t go back for more, put off by the stories’ continuation from the previous volume.

It’s only now, with the release of Is This How You See Me and Tonta, that I am reading the stories that followed up The Love Bunglers in a complete form. They blew me away. The effects Jaime’s going for at any given moment may be subtle, but they accumulate, and this accumulation then becomes the true effect, and why I analogize it to aging: There’s this sheer weight that results from how things just continue to happen, and each time they hit you with what feels like more force, even as the moments themselves are minor ones. This is a true-to-life feeling that is very hard to capture. It’s present in the relentless pace of Charlie Kaufman’s masterpiece Synecdoche, New York, but that is a movie too intense to rewatch for many. Jaime’s work is built around you returning to it, which means it has to be somewhat inviting, and include levity.

Is This How You See Me focuses on the characters of Maggie and Hopey, introduced in 1981 as teenagers, now presumably in their mid-fifties, happily married to other people but still weighing the possibility of cheating with their ex. The characters return to a “punk rock reunion” in their hometown, to reminisce on the past with old friends, and old characters we haven’t seen in years appear, visibly older than when they were last drawn, but still recognizably themselves. This plot lends the comic some elements of nostalgic fan-service that I intellectually feel an aversion to. It feels almost like the plot is designed transparently for those purposes. Bringing back old characters would strike me as a crass project in the pages of X-Men or Legion Of Super-Heroes, but the naturalism of Jaime’s approach means that it allows him to show me things I legitimately haven’t seen in a comic book before. It’s probable they’ve been in movies or books, but I would argue they work better in comics.

For instance, there’s a scene where the reunited cast are showing each other photos on their phones. This is a normal thing people do, and so surely it has been depicted in a film. But in a comic, there’s this weird meta element to it. Smartphones have text message conversations appear in little word balloons, right? The word balloon being a technique comics used to depict speech, as part of their normal communication system of images. Then, when interacting in physical space, people show pictures to each other, using this device they usually use for the mimesis of speech over distances, but they’re communicating using pictures to show what their life is like. Which is what the comic itself is doing more generally. So, there’s there’s this semiotic quality to the gesture of the outstretched hand with phone in it which feels really profound when depicted in comics, while it would feel sort of stupid and uncinematic in a movie, where the aging theater audience would have to squint and ask their neighbor what is being shown in the text message they’re seeing on screen.

Similarly, we see the married couple of Maggie and Ray, separated from each other for the length of the weekend, fretting over how much they should be in communication, drafting texts and deleting them. There’s an intimacy people who live with each other share, where much of what they encounter apart from the other person they want to talk to them about, because to be close to another person is to have them in some ways always present inside your head. Depicting the writing of a text, and then the decision to delete it, captures both the intimacy of a couple and the intimacy of one’s own private thoughts, in a way that only a form with the intimacy of a comic is able to depict effectively. Prose alone can’t capture the fluctuations of posture and self-presentation which is the heart of deleting a draft.

Concern for one’s image is depicted as well in the title pages to individual chapters, showing characters taking pictures of themselves in mirrors with their phones. These pages seem to depict not so much the cultivated selfie but the self-awareness of the drafting process, the titles above them taking on a certain poetry, built around the words spoken to oneself unconsciously that are the opposite of the language one chooses to send in a message to convey a precise thought.

This stuff really impressed me, and it all fits within a language of small gestures. While there are tons of books that are about how connection works in the digital age, it also always feels like that stuff is a commentary on how young people live. I’m not sure I’ve seen anything as interested in how people in middle age use these devices. Of course, it’s possible examples exist in work targeted to older audiences, and I just missed it because it wasn’t marketed to me.

It was actually Jaime’s other 2019 book, Tonta, that spoke to me more. Here, the aging the book is about is a coming-of-age thing about a high school student, and the book has this spirited youthful quality to it from the outset. While other, darker, plot elements unfold as it goes on, what was interesting to me is that the noir-like narrative that exists as a counterpoint in the finished book might not have even seemed part of the same story to a reader of Love And Rockets, where the character nicknamed Tonta just sort of suddenly emerged. There’s even a few pages in this collection given over to narration by Ray, who otherwise doesn’t appear in the book. These elements don’t seem dissonant or like they don’t belong. It just makes the book itself feel loose, like it feels as free and exploratory as a teenager looking for something to do. Placed together inside a book, the disparate threads become united by having a main character to pay attention to how developments of the plot affect her. The book has a real tonal arc as it unfolds, and the way the book gets you in its grip from such a goofy start seems to replicate how the stories about the Maggie character developed over time, here captured in miniature.

The sum of these two books will at some point only be a portion of a future volume of the Love And Rockets library, the formatting of the Perla La Loca and Penny Century books I mentioned earlier. There are portions from recent issues of Love And Rockets that are natural continuations and codas from these books, and what tapestries these fragments will be woven into is unknown to me. Another gutpunch could be just around the corner or years in the offing. There’s really no way to know what the future holds.

2 notes

·

View notes