#nyuifa

Text

Preserving Leaf Paintings in an Anglo-Indian Commonplace Book, 1822-1825

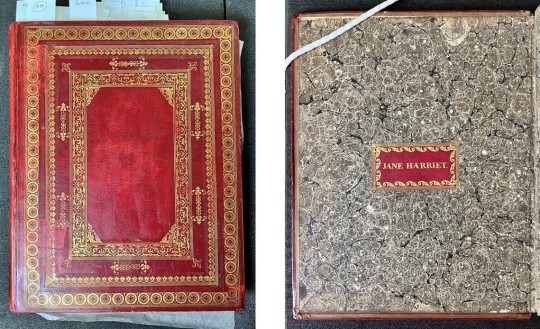

Hello, I’m Alexa Machnik, a third-year graduate student at the Conservation Center, Institute of Fine Arts, NYU. I first came to the Barbara Goldsmith Preservation & Conservation Department in Fall 2022 as a student in the graduate course, Conservation in Context, taught by Laura McCann, Director of Preservation. During this course, we delved into the world of library conservation, exploring the value systems that guide preservation decision-making and treatment action in academic research libraries. One of my class projects involved rehousing delicate leaf paintings from an early 19th-century commonplace book, or friendship album, part of the Fales Library holdings in the Special Collections at NYU Libraries (figs. 1-2) [1]. In honor of Preservation Week, I will share the intriguing history of the book and discuss the decisions that were made to preserve the leaves.

Figure 1 [left]: Front cover of the commonplace book, bound in gold-tooled red morocco leather.

Figure 2 [right]: Ownership label of “Jane Harriet [Blechynden]” on front marbled pastedown.

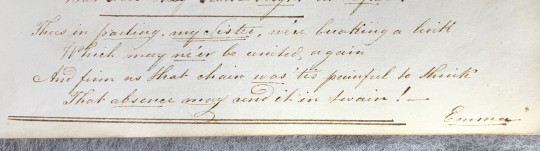

The book in question was compiled by Jane Harriet Blechynden (1806-1827) in England between 1822 and 1825. It holds her personal collection of handwritten and acquired materials, with contributions from her sisters, Emma and Sarah, who wrote original poems about sisterhood, separation, and their Anglo-Indian ancestry. The three women were the daughters of a British merchant residing in Calcutta, and while born in India, they were educated in England [2]. There is not a great deal known about Jane Harriet’s life in England, but her impending return to India in 1825 is documented in an emotional verse by Emma (fig. 3):

“Thus in parting my sister we’re breaking a link / Which may ne’er be united again / And firm as that chain was ‘tis painful to think / That absence may send it twain.”

Figure 3: Excerpt from the original poem, “Parting and a Meeting,” signed by Emma.

Jane Harriet’s book offers insights into her personhood, social connections, and sensibilities as an artist and collector. In addition to written entries, she inserted a compendium of acquired materials–pressed flowers, her own original drawings, and numerous paintings–between pages of the book (figs. 4-6).

Figures 4-6 [left to right]: A small sampling of the ephemeral treasures found in the book, including a dried pressed flower, a drawing on pith possibly by Jane Harriet, and a cut-paper silhouette.

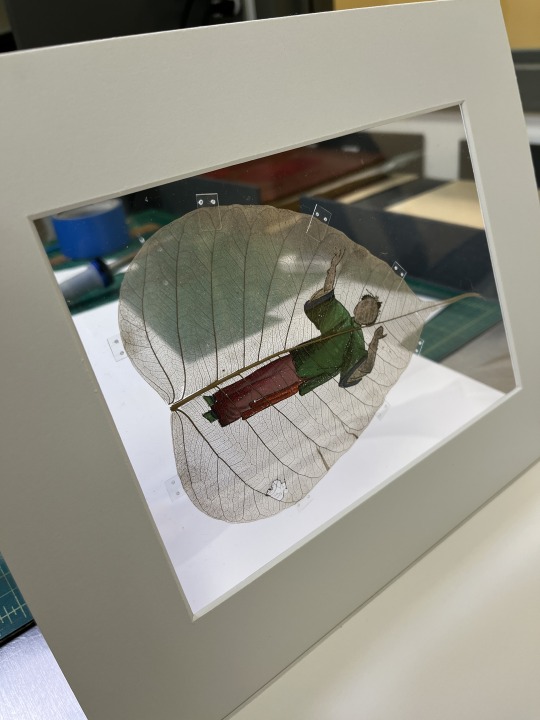

Notably, six of these paintings are executed on the dried leaves of the Bodhi tree, a sacred plant indigenous to Asia with distinct spade-shaped, long-tipped leaves (fig. 7) [3]. Although leaf painting has origins in Buddhist traditions, by the time Jane Harriet collected her leaf paintings, it had already evolved into a form of Chinese export art in Europe. Her leaves depict secular scenes of contemporary life in China and botanical subjects, which are typical of the export genre (fig. 8). Their inclusion in the book implies that Jane was among the many people who partook in the avid collecting of China trade goods during the first few decades of the 19th century, a time when European fascination for Chinese culture and art was at its peak.

Figure 7: A leaf painting, as found loose in the book and partially lifted to show the thin, translucent nature of the leaf support.

Figure 8: Another leaf painting from the book, oriented with the leaf tip at the bottom of the image, depicting flowers and a butterfly.

The initial rush of excitement that I felt at finding the leaf paintings soon turned to concern as I gave thought to their long-term preservation at NYU Libraries, where researchers are expected to handle the book. The leaf paintings were loose in between the pages, which raised a series of “what ifs” about the potential dangers they could encounter. What if the leaves slip from the book? What if they bend or break as the pages are turned? What if the painted surfaces become abraded? The paintings were made with opaque pigment-based watercolors on exceptionally delicate, skeletonized leaves that have been primed with a thin organic coating. Despite being intact, their inherent fragility means that they are vulnerable to even the slightest touch. After considerable discussion, the Conservation Unit decided that in order for the leaf paintings to be preserved and safely accessed by researchers, they should be housed separately from the book.

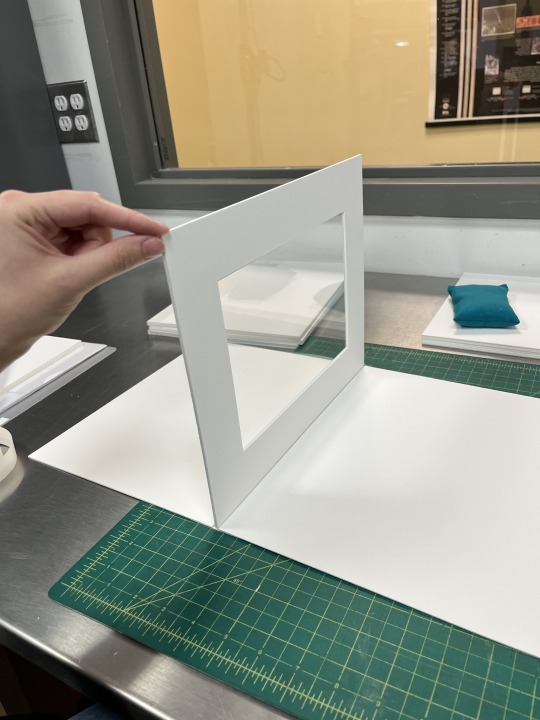

I thoroughly examined the condition of the leaves and the painted surfaces in order to make a housing recommendation. Despite some minor damage, all were in stable condition. Thus, the ideal housing would provide support to prevent any further damage, such as paint loss and leaf breakage, and at the same time allow the leaves to maintain their translucency. To achieve this, I opted to mount them in double-sided window mats with a support made from clear polyester film, or Mylar® [4]. The addition of the Mylar® would not only create a stable surface for the leaf paintings but also enable the viewing of both sides (fig. 9).

Figure 9: View of the double-sided window mat with a Mylar® support.

My next challenge was to figure out how to mount the leaves onto the Mylar® support without the use of adhesive [5]. After consulting with conservation staff and creating mock-ups, short, discreet Mylar® tabs were selected as the best option to secure them into place (figs. 10-11). For this process, I positioned a single leaf painting onto the support and selectively placed the tabs around its perimeter, making sure the tabs did not overlap any areas of paint. I then used a handheld spot-welding pen to fuse the tabs to the support. Since this process was done in-situ, near the leaf, it required lots of precision practice and encouragement from colleagues before I felt confident enough for the task.

Figure 10: Detail of a mounted leaf painting. Notice that the Mylar® tabs are welded just outside the leaf and extend minimally over the edges, holding it in place with gentle pressure.

Figure 11: The backside of a mounted leaf painting viewed through the Mylar® support. This gives researchers access to the painting’s verso, where an underdrawing and other signs of artistic process can be discerned.

At the time of writing this post, I successfully housed the six leaf paintings in their double-sided window mats (figs. 12-13). This housing project, while complete, is just one part of the ongoing effort to preserve the commonplace book, and the Conservation Unit is continuing work on other elements of the book to ensure its safe return to Special Collections.

Figure 12: Example of the completed housing, showing the front of a leaf painting.

Figure 13: Back of a leaf painting.

Though my involvement in the project has come to an end, I have gained a very special appreciation for the commonplace book and the preservation challenges it presents. The experience of learning directly from NYU Libraries Special Collections was especially invaluable, providing me with opportunities to participate in complex decision-making processes unique to large research libraries driven by user needs. Before signing off, I’d like to extend my gratitude to my supervisors, Laura McCann, Director, and Lindsey Tyne, Conservation Librarian, and the entire team at the Barbara Goldsmith Conservation Lab for their unwavering support and enthusiasm throughout this project. Thank you all very much!

Notes:

[1] A commonplace book is a centralized place for an individual to record information, whether it be their personal thoughts or quotes from outside literary sources. Friendship albums, by contrast, contain handwritten entries from the family, friends, or acquaintances of the owner (often female). Both forms of commonplacing sustained popularity in Europe and America throughout the 19th century. To learn more about this fascinating literary genre, see Jenifer Blouin, “Eternal Perspectives in Nineteenth-Century Friendship Albums,” The Hilltop Review, Vol. 9, Issue 1 (2016) and Victoria E. Burke, “Recent Studies in Commonplace Books,” English Literary Renaissance, Vol. 43, No. 1 (2013), 153-177.

[2] Much of what is known about Jane Harriet (also known in her family as Harriet) comes from the Blechynden papers in the British Library (Add. Mss. 45578-663). This large holding contains the diaries of her father, Richard (Add. Mss. 45581-653), and older brother, Arthur (Add. Mss. 45654-61). For a secondary account of the Blechynden household, see Peter Robb, Sentiment and Self: Richard Blechynden’s Calcutta Diaries, 1791-1822 (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2011).

[3] Michele Matteini, “Written on a Bodhi tree leaf,” Anthropology and Aesthetics, Vol. 75-76 (2021), 45-58.

[4] The design of the double-sided mats is based on an instructional guide made available by the Library of Congress. “Double-Sided Mat,” Library of Congress, accessed 1 February 2023.

[5] We chose not to use adhesives or traditional paper-hinging techniques to mount the leaf paintings for several reasons. As noted, the paintings are on fragile, non-paper-based supports that have an organic coating, which may be derived from plant gum. The leaf supports are thin, translucent, and highly vulnerable to breakage, so applying hinges directly with adhesive might permanently alter their appearance or risk further damage to the leaves over time, especially if they need to be removed from the housing in the future.

Photographs: Alexa Machnik

#NYULibraries#NYUSpecialCollections#FalesLibrary#nyuifa#nyuart#librarypreservation#libraryconservation#collectionscare#artconservation#paperconservation#bookconservation#artpreservation#preservingthepast#PreservationWeek#preservationweek2023

208 notes

·

View notes

Photo

At long last 🎓 #master @nyuifa @nyuniversity (at Washington Square Park)

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Self-Portrait as Mao Zedong by Cameroonian #photographer #SamualFosso 💧 in the small and great #DukeHouseExhibition “chin(A)frica: and interface” @nyuifa 💧 if only the rooms were grander (at The Institute of Fine Arts, NYU)

0 notes

Photo

Went to a great talk tonight between Elizabeth Ferrer @evferrer and Miguel Luciano at the @nyuifa —I haven’t been to the Institute (the former Doris Duke Mansion) in years!!!) Luv the juxtaposition of Miguel’s art and the faded grand drapery! @evferrer #miguelluciano #evferrer #nyu #instituteoffinearts #interestingart #bric #bricartsmedia #melissaederart #puertorico #rideordie #trickedout #piragua

#interestingart#nyu#bricartsmedia#trickedout#miguelluciano#evferrer#bric#piragua#rideordie#melissaederart#puertorico#instituteoffinearts

0 notes

Photo

@nyuniversity is going to have purchase The Cloisters for me to think there is a more magical campus property. . . . Here's to another afternoon at @nyuifa! . . . #nyu #NYC #museummile #uppereastside #citylife #scouting #makingmovies #work #werk #dukehouse (at New York University Institute of Fine Arts Ifa)

0 notes

Photo

Huge icicles at #Cornell #Kapihan #NYUIFA

0 notes

Text

Preservation Week 2023

Virtual Presentation: Conservation of Balinese Shadow Puppets from the Mabou Mines Archives

Date: Tuesday, May 2, 2023, 1:00 - 2:00 PM (EST)

Location: Virtual Event/Zoom

Registration: https://nyu_preservation_week_2023.eventbrite.com

Image: a Balinese shadow puppet from the Mabou Mines Archive, NYU Special Collections.

Since last November, Conservation Center student Peiyuan Sun has been conducting research and conservation treatment on a group of Balinese shadow puppets from the Mabou Mines Archive (MSS.133). In this presentation, she will talk about the information that she has discovered regarding the history and manufacture of these materials and the ways in which she is actively working to make these items more accessible to future users.

Peiyuan Sun received her B.A. in Art History from NYU in 2018. She is in her final year at NYU’s Institute of Fine Arts, where she is a candidate for an M.A. in Art History and M.S. in Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works. Since fall 2022, Peiyuan has been working as an Andrew Mellon Fellow at the Barbara Goldsmith Preservation and Conservation Department for her curriculum internship under the supervision of Preventive Conservator Jessica Pace.

This event is presented in celebration of Preservation Week, an annual initiative of the American Library Association aimed at connecting our communities through events, activities, and resources that highlight what we can do, individually and together, to preserve our personal and shared collections.

#PreservationWeek2023#PreservationWeek#NYULibraries#NYUSpecialCollections#FalesLibrary#nyuifa#nyuart#librarypreservation#libraryconservation#collectionscare#artconservation#artpreservation#preservingthepast

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

FILM INSPECTION: THE EARLY FILMS OF BETH B

by Emily Jenne, Institute of Fine Arts Conservation Center graduate student

Beth B, one of the most influential filmmakers to emerge from the generative chaos of the 1980s downtown scene, is known for her transgressive head-on confrontation of power structures and sexual politics. She formed the independent film production company B Movies (a play on low-budget films) with her partner Scott B, with whom she has worked over the years along with a panoply of collaborators, downtown luminaries such as Jack Smith, Arto Lindsay, Pat Place, John Lurie, Bill Rice, Gary Indiana, James Nares, Kiki Smith, Tom Otterness, Richard Edson, Vivienne Dick, James Russo, Richard Prince, Ann Magnuson, Jenny Holzer, Richard Kern, Kembra Pfahler, James Habacker, Dirty Martini, Thurston Moore, and Kai Eric (the list goes on). She is still active today, and her recent documentaries zero in on burlesque, no-wave provocateur Lydia Lunch, and the painter Ida Applebroog (who also happens to be Beth B’s mother).

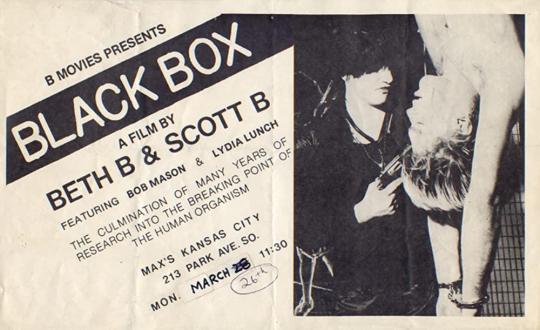

Flyer for ‘Black Box’

As a longtime Beth B fan myself, I was thrilled to have the opportunity to work on several of her early films as they entered NYU’s Special Collection (Beth B Papers, MSS.614; Scott and Beth B (B Movies) Records, MSS.622). This included: G Man (1978), Black Box (1979), The Trap Door (1981), Salvation (1987), Belladonna (1989), and Visiting Desire (1996), as well as a copy of Un Chant d’Amour (1950) the first and last film by French writer Jean Genet, famously banned for its explicit content. As a graduate student specializing in both time-based media and paper conservation at the Institute of Fine Arts NYU, I am often asked where these two seemingly disparate fields overlap. The work I’ve done at the Barbara Goldsmith Preservation & Conservation Department is an excellent example of the two working in tandem. The Beth B collection, for example, has both a media component (the films) and an accompanying paper element (posters and other ephemera).

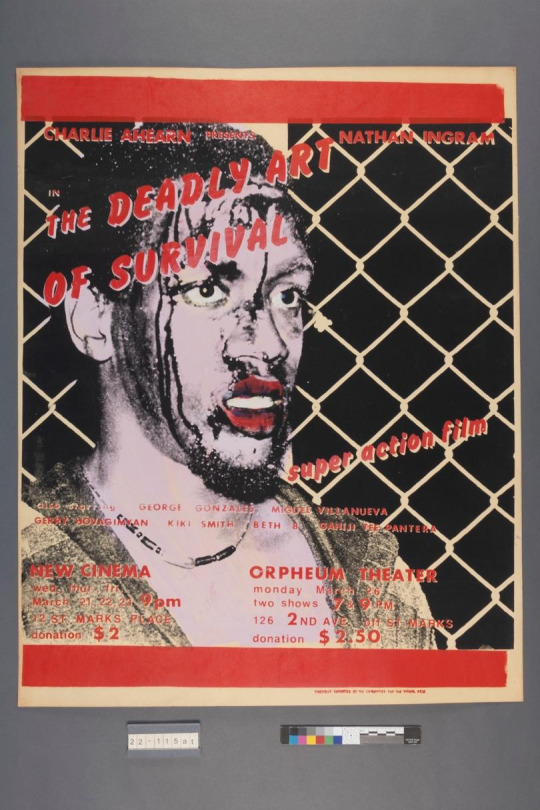

‘The Deadly Art of Survival’ poster, photograph by Dawn Manokowski

Film preservation begins with an assessment logging current conditions and identifying the media, which will determine the best practices for storage. The first order of business is identifying the film base as cellulose nitrate, acetate, or polyester. The film gauges present in the Beth B collection, 16mm and Super 8mm, ruled out one possibility, cellulose nitrate which was never used as an 8mm or 16mm substrate in the West. From there, acetate and polyester could be distinguished using a very high-tech piece of equipment, 3D movie glasses. A pair of polarized 3D glasses folded in half at the nose can be used for a polarization test. When slid between the lenses, a polyester base will birefringe, acetate will not (birefringence is a phenomenon of optical anisotropy in certain materials that causes distinctive visual undulations at changing angles). In the end, all of the films were found to have an acetate base.

The film inspection bench in the Barbara Goldsmith Preservation & Conservation Department.

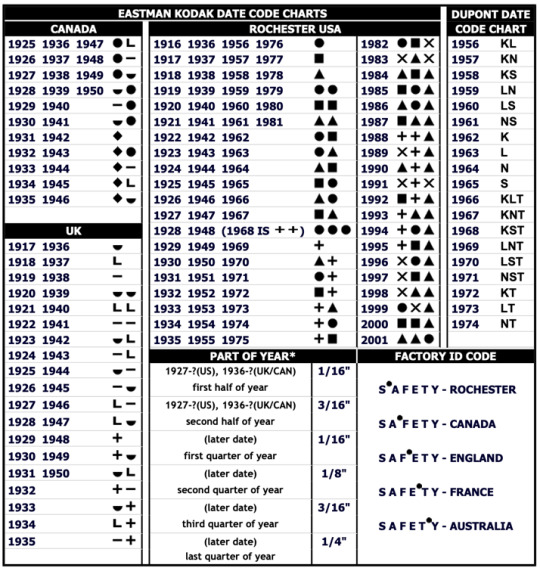

Further information about the film stock can be determined from clues in the edge code. Using a loupe and cross-referencing with an edge code chart, the year and even the location of manufacture can be established. The placement of a dot within the word ‘safety’ notes the location (acetate film base is known as ‘safety film’ in contrast to its highly reactive and flammable predecessor, cellulose nitrate). The film stock in the Beth B collection was manufactured in Rochester, NY.

Kodak edge code identifying Rochester, NY as the manufacturing location.

Eastman Kodak Date Code Chart

Information on the soundtrack format was also noted, the Super 8mm reversal films had a magnetic soundtrack, and the 16mm reversal films had a variable density optical track. Other relevant information was also recorded such as instances of surface abrasion, broken sprocket holes, number and character of splices, and any annotations on the head or tail leader (often instructions for the projectionist).

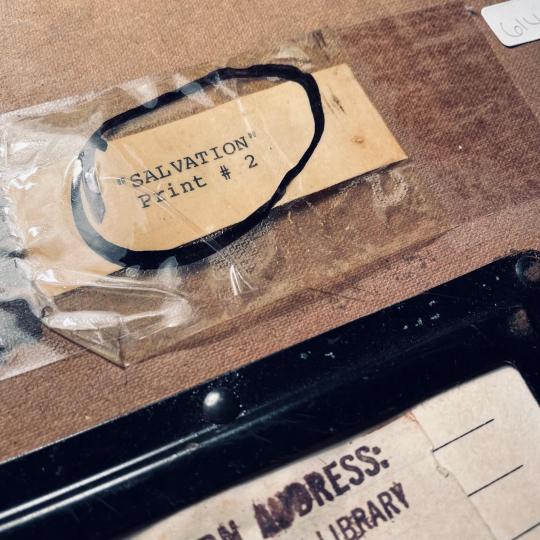

‘Salvation’ Print # 2

‘The Trap Door’ 8mm reel.

The major concern with acetate film base is deacetylation, an irreversible form of deterioration colloquially known as ‘vinegar syndrome’ for its distinctive acidic odor which can be detected at concentrations as low as 1 ppm. Deacetylation is essentially a reversal of the synthesis steps used to make the acetate base, and the reaction produces acetic acid which can also have a detrimental effect on the other component layers of the film. Acetic acid can soften the gelatin emulsion layer and accelerate fading of color dyes in color film. Deacetylation also leads to warpage, embrittlement, channeling, and shrinkage of the film base by as much as 10%. Shrinkage beyond 0.8% makes it dangerous to project the film.

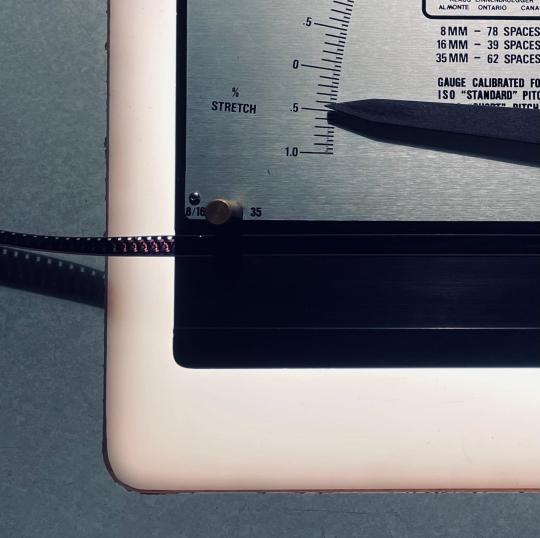

Film shrinkage gauge.

Deacetylation is exacerbated by high humidity and fluctuations in temperature, but further damage can be mitigated with correct storage conditions. The industry standard for measuring the extent of deacetylation is with AD strips, a type of targeted litmus test, which measures acidity on a scale of 0 (blue, indicating no deterioration) to 3 (yellow, which indicates critical condition). In conjunction, multiple readings taken with a film shrinkage gauge can be used to determine the average shrinkage level of the film.

An 8mm film splicer in action.

‘Trap Door’ film reel storage case.

The films in the Beth B collection were found to be in generally good condition, and minor preservation interventions included the removal of tape residue and splicing of new labeled extensions onto the existing head and tail leader. The copy of Un Chant d’Amour, now upwards of 70 years old and suffering more from the effects of deacetylation in contrast the Beth B films, is a good reminder of the importance of consistent low humidity, low-temperature storage in prolonging the life of acetate-based films, just the kind that these films will receive in their new home at NYU.

Film Poster for ‘Lydia Lunch: The War is Never Over’

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy Preservation Week! (Part 3 :)

Hello again, and Happy Preservation Week, everyone!

This is Part 3 of our Preservation Week 2021 blog series, if you missed Part 1 or Part 2, feel free to check them out first!

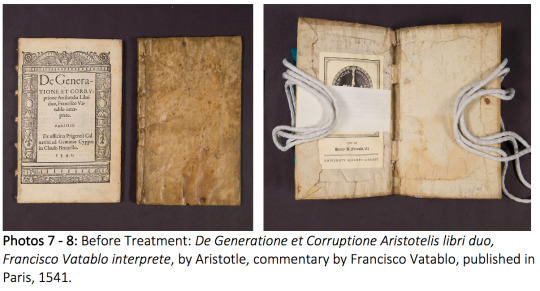

Not long after I finished treating my set of 1891 publisher’s bindings (see Part 2), I had the chance to conserve/preserve one of their Renaissance ancestors. The little book shown in Photos 1-2 is a 1541 Latin translation of a text by Aristotle, and its parchment cover is an example of 16th century recycling!

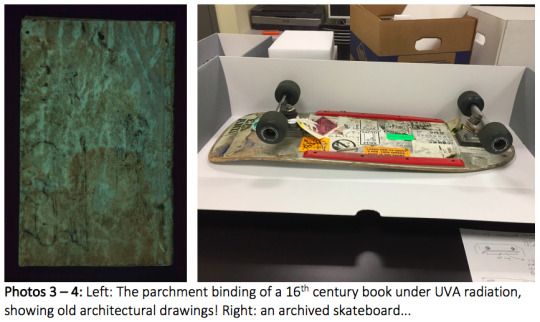

This type of binding is a “limp vellum” laced-in case, and it was made from a sheet of parchment that someone had previously used to sketch architectural columns (see Photos 3-4.)

In Photo 3, if you turn your head sideways, you can see the base of a column near the bottom left corner, and on the right side, near the spine, you can see a drawing of a Corinthian column. These drawings are difficult to see under normal lighting conditions, but the ink (probably iron gall ink) shows up very well under UV. The recycled parchment binding was probably very flexible when the book was bound, but today the cover is stiff and difficult to open. As you can see, it has also detached from the text, and it functions more like a protective folder than a book cover. Apart from this obvious structural problem, the book is in relatively good condition, and I took a minimally-invasive approach to treating it, under the supervision of Lou Di Gennaro, Special Collections Conservator.

I began by adding a few teeny tiny spine linings between the raised bands on the spine of the text block. The book originally had a pair of parchment spine linings, but these are still attached to the parchment text: in Photo 2, a pair of horizontal strips of parchment span the fold in the parchment case. These two strips of parchment were adhered to the back of the text, and this was the main attachment point between the text and the parchment covers. The text could still be handled and read without its original spine linings, but it was more vulnerable to damage (especially because the spine's loops of sewing thread kept trying to slip off the raised bands!) We decided to apply small strips of Japanese long-fibered kozo paper between the raised bands (Photo 5). I applied these with wheat starch paste (Photo 6) and when they had dried they provided a measure of almost-invisible strength to the spine.

After the spine was consolidated with kozo paper, we considered how to address the binding. It would have been very satisfying to reattach the parchment case to the text... it was clear that this approach would have caused even more damage to the book eventually, though, because of the force that would be required to open it. Fifty or more years ago, conservators might have taken the text apart, washed all of the pages, resewn the book, and given it a brand new parchment cover. In the past, this was considered the best way to preserve a 480-year-old book, but today, most conservators agree that it’s better to preserve these books in their current condition, as much as possible. We decided to leave the parchment cover separate from the text, and to allow it to continue functioning as a protective wrapper. The only difficulty with this decision was that the inside of the parchment cover had several sharp edges that were scratching the outermost pages. Most books have a few blank pages at the beginning and end of the text (“endleaves”), because the first and last pages are very vulnerable to damage. This little book didn’t have any sacrificial endleaves, so we decided to add some (Photos 7-8).

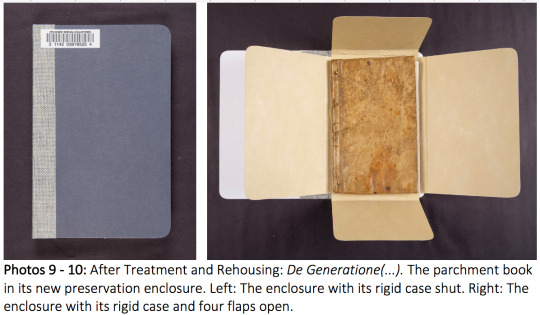

I chose a modern paper of a similar weight and color, and I folded two pieces of it to create a pair of endleaves at both the front and back of the book. Using wheat starch paste, I adhered the folds to the very edge of the first and last pages. The new endleaves look a little too clean when compared to the original paper, but they will protect the first and last pages from abrasion. They can easily be removed from the book later, if another conservator disagrees with this approach, and believe me, there is a long tradition of conservators questioning the decisions of their predecessors! Finally, I created a custom-fit preservation enclosure for the book (Photos 9-10).

This 4-flap wrapper with a rigid outer case will protect the book from light damage, dust, and abrasion, and it’s always better to slap a barcode on the enclosure than on the rare book itself! Additionally, this wrapper will buffer the parchment from fluctuations in temperature and humidity; parchment can shrink or expand quickly, depending on how dry or humid the air is, and over time these cycles of expansion / contraction can weaken the binding. Again, this treatment involved a bit of “conservation” and “preservation.” The physical alterations that I made to the book were minimal, and these changes are more preventive / functional than aesthetic. The preservation enclosure will make the book look a little less pretty on the shelf, but it’s much safer now!

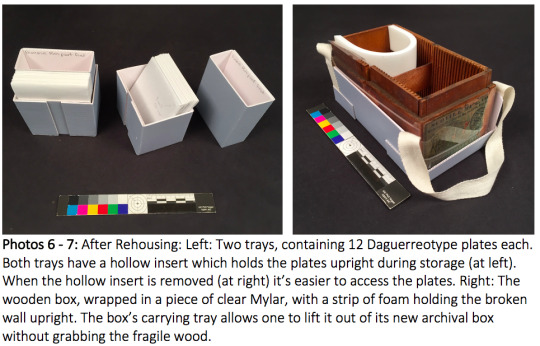

Thanks for reading, and stay tuned for tomorrow’s installment of our Preservation Week 2021 blog series… I’ll discuss the preservation of a set of 24 unexposed Daguerreotype plates and the wooden box that they were purchased in (see photos below!)

-Cat Stephens

#PreservationWeek#Preservation#Conservation#Libraries#SpecialCollections#TodayInTheLab#NYU#NYULibraries#AmericanLibraryAssociation#ALA#NYUIFA

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy Preservation Week! (Part 1 :)

Happy Preservation Week, everyone!

I’m Cat Stephens, an Andrew W. Mellon Fellow studying Library & Archive Conservation at NYU’s Institute of Fine Arts. At the IFA, I’m earning an MA in the History of Art and Archaeology, and an MS in the Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works, specifically in the conservation of books, paper objects, and photographs.

Students in my graduate program have the option to spend their year-long graduate internships almost anywhere in the world, but I chose to stick around and intern at the NYU Libraries’ Barbara Goldsmith Preservation & Conservation Department... In addition to being awesome at their jobs, the conservators here are excellent teachers, and I’ve always been impressed by the range and volume of treatments that they perform every year! Additionally, NYU has done an impressive job of reducing the spread of Covid-19 on campus, and I feel very lucky that my internship was not severely impacted by the University’s precautionary measures. Since September 2020, the library’s preservation staff and I have had the option to work in the library for 2-4 days every week, and we catch up on paperwork during our teleworking days.

Over the last seven months I’ve worked on many treatments that have helped me understand the finer points of library preservation, and I’ll describe four of my favorite preservation/conservation treatments for you over the next four days. These treatments include a 19th century publisher’s binding, a 16th century book bound in recycled parchment, a wooden box full of unexposed Daguerreotype plates, and ... a skateboard??

But first, unless you’re a library or museum professional, you may be wondering what Preservation Week is, and how does “preservation” differ from “conservation?” For cultural heritage institutions, Preservation Week is a yearly opportunity to draw public attention to the importance of preserving cultural heritage materials of all kinds. These materials may include modern books, medieval manuscripts, audio/visual materials like VHS tapes and home movies, photographs, scrapbooks, textiles, digital data, paper documents, and metal, wood or glass objects, just to name a few. Many of these materials are held in libraries and museums for public enjoyment, but perhaps many more are sitting in our basements and attics! If you have special things at home that you want to preserve, there are many online resources available to you, and I’ve provided links to some of them at the end of this post.

For conservators and other preservation professionals, Preservation Week is a good time to consider the enormous range of objects that we’re tasked with caring for, and to think about new ways to preserve and conserve them for the next generations. In libraries and museums, “preservation” and “conservation” refer to slightly different activities, but they both contribute to the wellbeing of cultural heritage objects. “Conservation” refers to any physical interventions performed on an object, such as cleaning, making repairs, or compensating for parts that have been lost. A conservation treatment can reduce the stains in a flood-damaged drawing, or it can transform a pile of ceramic sherds back into an ancient vase. “Preservation” usually encompasses the activities performed around an object which will minimize the object’s chemical and physical deterioration over time. Preservation activities include the making of enclosures to protect objects from physical harm, dust, or light damage, the management of pests, and the careful control of temperature and humidity in storage facilities. Preservation and conservation are two sides of the same coin, and many argue that “preservation” is the broader term which includes conservation activities. This point of view is often held in libraries, where the objects (usually books) are not just static relics of the past, they are vehicles of information; to access this information, books must be handled, and they must be able perform a kinetic function. For this reason, any conservation treatment that restores functionality to a broken book can also be considered “preservation.” Of course, many old or rare books have been digitized and made available online, but even so, scholars often want to verify and augment their online research by perusing the original book… there’s no digital substitute for the real thing :)

Thanks so much for reading, and stay tuned for tomorrow’s installment of our Preservation Week 2021 blog series, where I’ll discuss the conservation of a novel published in 1891 (photos below!)

-Cat Stephens

Some At-Home* Preservation Resources:

American Institute for Conservation (AIC): “Caring for Your Treasures”

American Library Association: “Saving Your Stuff”

FEMA (Federal Emergency Management Agency): “Salvaging Water-Damaged Family Valuables and Heirlooms” ... (Fact Sheets are available in English, Chinese, Vietnamese, Haitian Creole, Portuguese, and Spanish):

Minnesota Historical Society: Preserving “Clothing and Textiles”

National Archives: “How to Preserve Family Archives (Papers and Photographs)”

*But sometimes a problem is so complex that it requires a conservator… AIC’s “Find a Conservator” tool can help! https://www.culturalheritage.org/about-conservation/find-a-conservator

#PreservationWeek#Preservation#Conservation#Libraries#SpecialCollections#TodayInTheLab#NYU#NYULibraries#AmericanLibraryAssociation#ALA#NYUIFA

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy Preservation Week! (Part 5 :)

Hello again, and Happy Preservation Week, everyone!

This is the 5th and final installment of our Preservation Week 2021 blog series, if you missed Part 1, Part 2, Part 3 or Part 4, feel free to check them out first!

In our previous post (Part 4), I described the preservation of a set of unexposed Daguerreotype plates and the original wooden box they were issued in. For those objects, I made an (admittedly) complex preservation enclosure that will keep everything safe in storage, but it might be a little confusing to the next person who opens the box. Sometimes it’s hard to make a simple, easy to use preservation enclosure… you find yourself making a series of “simple” decisions that snowball into something complex and baffling!

In this, our final Preservation Week post, I’ll discuss a preservation enclosure that needed to fulfill a lot of different requirements, and the object that it houses is one which I never expected to find in a library! This object is part of the Outpunk Archive at NYU, which contains materials from 1989-1998 relating to Outpunk (both the zine and the queercore music label). While most of the collection consists of papers, photographs, and music recordings, there are also several T-shirts and ...a skateboard!

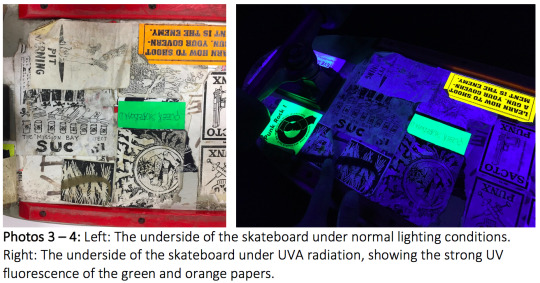

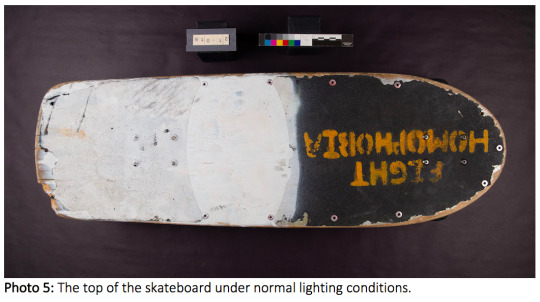

Apparently, a member of the Riot Grrrl movement owned and adorned this skateboard: one half of the top of the board is spray painted white, and the words “FIGHT HOMOPHOBIA” are spray painted in orange on the other half (Photo 1). Lots of stickers, self-adhesive labels and zine-style xeroxed drawings are pasted to the bottom surface of the board (Photo 2). This person probably lived in San Francisco in the late 1990’s, because one drawing asserts that “The Mission Bay Project SUCKS!” (Photo 3).

A few of the papers are bright yellow, orange or green, and these glow brightly under UV, suggesting that the papers contain daylight fluorescent pigments (Photo 4). These pigments look unusually bright in sunlight because they absorb UV radiation and reflect it back to the eye as visible light. While we were examining the top of the board under UV, we found yet another message hidden beneath the white paint... at one point, the owner of this skateboard believed that “FASHION IS A SCAM”, but she later decided to paint over this message (Photos 5-6).

So... why the heck was this skateboard in the conservation lab? Well, it’s a lot bulkier than the average library book, and since the wheels work perfectly we couldn’t just leave it on a shelf! We needed to give the skateboard a preservation enclosure to keep it from rolling around in the stacks, or being mistaken for an NYU student’s property. Most of all, we wanted to give the skateboard a preservation enclosure to prevent its minor damage from getting worse: the plywood board is cracked and splintering at one corner, the sandpapery grip tape is flaking off around the edges, and most of the stickers and drawings are torn and/or curling. We briefly discussed whether we should perform a little conservation work to stabilize these parts of the board; in the end, we decided that we didn’t want to obscure evidence of the skateboard’s use, and everything was stable enough to withstand gentle handling. ...Some may be thinking, “COME ON, it’s a skateboard! This is ridiculous.” To that I say, it’s part of an archive now! We have to treat it carefully, so it lasts a long time. :)

The library’s curators are interested in showing this skateboard during classes, and it’s possible that the object will be requested frequently in the Special Collections reading rooms. As you may recall, the main purpose of my Daguerreotype enclosure was to keep all of the components safe during storage and transit, but the skateboard’s enclosure needed to fulfill two additional requirements: it needed to be simple enough for anyone to unpack/repack easily, and because the skateboard is double-sided, the enclosure needed to function as a double-sided display mount. Under the supervision of Jessica Pace, Preventive Conservator, I created a simple preservation enclosure that would protect the skateboard and allow the curators to safely display either side.

We started by ordering a custom archival box with a drop-wall, which allows you to remove a bulky object more easily (Photo 7). Because the skateboard is a bit heavy and awkward, I also made a handling tray from cross-laminated sheets of archival corrugated cardboard. This tray (Photo 8) allows you to pull the skateboard out of the box, rather than lifting it. I also adhered strips of corrugated board to the bottom of the tray which adds a little more rigidity and allows for air-flow underneath when the tray is pulled out of the box. We decided it was best to store the skateboard wheels-down, so we had to find a way to prevent it from moving around in the box, or rolling off a table. Jessica thought it would be easiest to create bumpers on either side of the wheels, so I experimented with pieces of “Ethafoam” (low-density polyethylene foam, Photo 7). I cut four narrow strips of Ethafoam, and I wrapped them in a sheet of Tyvek fabric to prevent the foam from shedding bits of plastic inside the box. I used low-melt glue to adhere the foam to the handling tray, and I attached a pair of cotton pull-tabs to either side of the tray, to help people remove it from the box. The foam bumpers not only keep the skateboard stationary, but they can function as a display mount when someone wants to see the underside of the board. You can see the final enclosure in Photos 9-10, below:

Again, this was purely a preservation treatment, because the skateboard is in fairly good condition, despite minor damage. We chose not to repair this damage because it reflects the owner’s use of the skateboard, and the damage is not yet severe enough to threaten the object’s structural integrity. This simple preservation enclosure will prolong the life of the object and allow for conservation treatment in the future, if that becomes necessary. It may seem a little strange to treat this 20-year-old skateboard as though it were an ancient relic! I’ll admit, there were times when it felt a little absurd to apply my book and paper conservation skills to an object that (on the surface) looks like nothing special. If all goes well, however, the skateboard will survive for as long as the Daguerreotype plates or the 16th century parchment book... if so, the skateboard will teach future generations about late 20th century feminism and politics, queer history, punk rock, and alternative transportation!

Thank you so much for reading about our preservation activities at NYU Libraries this week, and thank you for supporting your local libraries!

Happy Preservation Week,

-Cat Stephens

#PreservationWeek#Preservation#Conservation#Libraries#SpecialCollections#TodayInTheLab#NYU#NYULibraries#AmericanLibraryAssociation#ALA#NYUIFA

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy Preservation Week! (Part 2 :)

Hello again, and Happy Preservation Week, everyone!

This is Part 2 of our Preservation Week 2021 blog series. If you missed Part 1, feel free to check it out first!

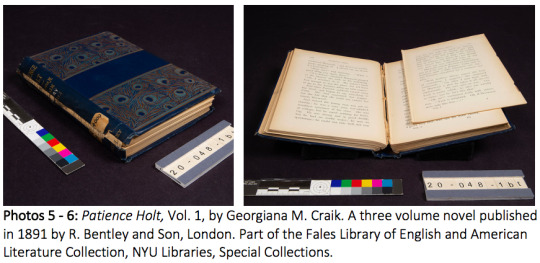

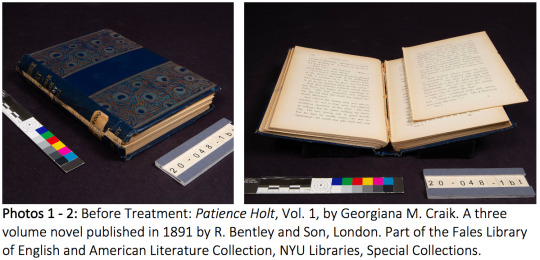

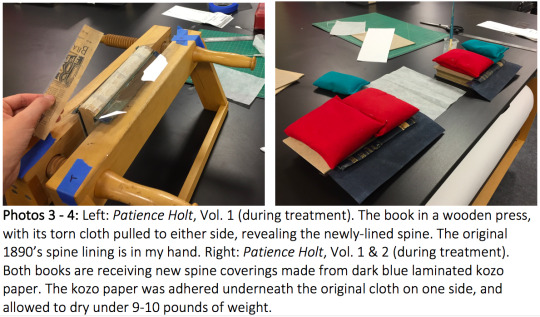

As I mentioned yesterday, “preservation” and “conservation” refer to slightly different activities in libraries and museums, but they both aim to prolong the lives of cultural heritage objects. Often, a conservation treatment can also qualify as a preventive measure (aka preservation), especially when the treatment reunites detached elements or returns a kinetic object (like a rare book) to a functioning state. This return to functionality preserves access to the text, which is especially important for out-of-print books, and those that haven’t been digitized yet. For example, the book shown in the photos below couldn’t be handled or read safely, because parts of it were broken, detached, and in danger of being lost:

This book is an example of a late 19th century publisher’s binding, and unfortunately, these colorful, mass-produced books are usually very fragile today. Publisher’s bindings were made to look attractive without being very expensive, so they were often produced using cheap, poor quality materials. For fragile books like this, damage usually occurs at the spine, because this area absorbs most of the physical stress imparted by reading. The damage shown in these pictures is commonly seen with 19th century publisher’s bindings: the spine cloth is brittle and torn in several places (Photo 1), and the sewing is breaking, resulting in the detachment of several pages (Photo 2). Ironically, this particular book may have been damaged by photocopying or by the process of microfilming, an outdated preservation technique that was popular in libraries until the advent of digital imaging. The simplest way to preserve this book might be to give it a custom-fitted box, which would protect the book from further harm and would hold all of the fragments together. Another way to preserve a book is to repair the damage and restore its function, in other words, to conserve it!

Under the supervision of Dawn Mankowski, Special Collections Conservator, I began conserving this book by carefully removing the book’s original spine lining, a piece of printed waste paper that was probably cut from an 1890’s magazine (Photo 3). This is much easier to do when the spine cloth is already torn! I put this interesting scrap aside, and I strengthened the spine with a new, stronger lining of Japanese long-fibered kozo paper (Photo 3). Next I took the detached pages and resewed them into the book, through the newly-strengthened spine. I then adhered the spine’s original printed waste lining on top of the work I had done, to ensure that none of the book’s original material was lost. Now that the structural work on the spine was finished, I could tackle the main aesthetic problem: the torn spine cloth. I laminated two sheets of kozo paper to make a thicker and stronger sheet, and I toned this laminated sheet dark blue with watered-down acrylics. I gently lifted the cloth away from the board joints and I adhered my blue kozo paper underneath the cloth on one side of the book (Photo 4). After the adhesive was dry, I molded the kozo paper around the curved spine and adhered it underneath the cloth on the other side of the book. I then adhered the original cloth fragments on top of the blue kozo paper, which acts as an invisible bridge underneath the torn cloth. Now the book can be handled and read without fear of exacerbating the old damage.

This was obviously a “conservation” treatment, because it involved a relatively invasive physical intervention to repair prior damage. This treatment has a significant element of “preservation” however, because all of the book’s original material was secured against loss, and the book’s kinetic function was restored, ensuring the preservation of the text. (Of course, another copy of the novel has been digitized and is available for free online, but you get the idea!) Throughout this process, I used water-based adhesives like methylcellulose and wheat starch paste, so that my work can be undone or redone by another conservator in the future. In book and paper conservation, we try to avoid synthetic adhesives like polyvinyl acetate (PVAc) as much as possible, because these tenacious glues are very difficult to remove. When we decide to conserve an object, we always strive for “reversibility” (or, more realistically, “re-treatability”) just in case our repairs fail or they cause unexpected harm to an object. Although it’s impossible to completely reverse the damage that occurred to this book over the course of 130 years, I have hopefully prevented the damage from worsening!

Thanks for reading, and stay tuned for tomorrow’s installment of our Preservation Week 2021 blog series: I’ll discuss the conservation/preservation of a book published in 1541, bound in recycled parchment (see photos below!)

-Cat Stephens

#PreservationWeek#Preservation#Conservation#Libraries#SpecialCollections#TodayInTheLab#NYU#NYULibraries#AmericanLibraryAssociation#ALA#NYUIFA

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy Preservation Week! (Part 4 :)

Hello again, and Happy Preservation Week, everyone!

This is Part 4 of our Preservation Week 2021 blog series. If you missed Part 1, Part 2 or Part 3, feel free to check them out first!

In Parts 2 & 3 I described two treatments that illustrate the ways in which conservation and preservation can be applied to old / extremely old library books. Today, I’ll focus mainly on preservation, and why we sometimes choose not to conserve an object.

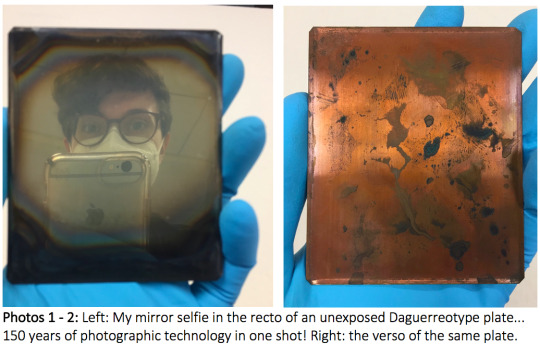

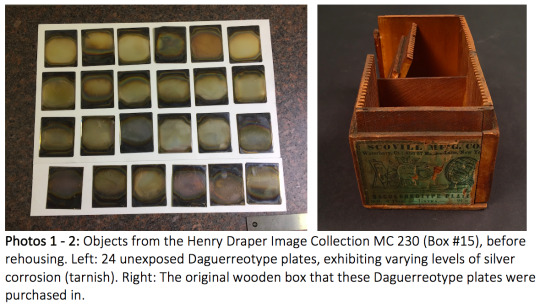

Last November, I had the opportunity to preserve an unusual piece of photographic history: a small, mid-19th century wooden box containing 24 unexposed Daguerreotype plates (Photos 1-2). The Daguerreotype was invented by Louis Daguerre around 1839, and it was one of the first commercially viable processes that made photography and portraiture more accessible to the general public. Daguerreotypes were commonly produced until about 1860, when they were replaced with less expensive photographic processes, like the Ambrotype and the tintype.

Each Daguerreotype plate is made from a very thin sheet of copper, which is covered with an even thinner layer of highly polished silver (Photo 1). The wooden box that the plates were issued in originally contained 72 plates. The box’s longer walls have 36 vertical channels cut into them, allowing two plates to be inserted into each slot. After a Daguerreotype plate was sensitized, exposed, and developed with mercury fumes, the photograph was immediately packaged inside a small glass-fronted case. An example of a Daguerreotype in its original case (from the Metropolitan Museum of Art) is shown below, in Photo 3. These cases were meant to protect the delicate beads of mercury-silver amalgam that form the image, and, if a relatively tight seal was achieved around the plate, the glass could prevent air pollution from tarnishing the silver.

The unexposed Daguerreotype plates in Photo 1 are exhibiting varying levels of silver tarnish and copper corrosion, because they were stored in their original wooden box for a very long time. The center of each plate is less tarnished than the edges, probably because the center was less exposed to the air. The manufacturer’s box has also seen better days, unfortunately: its lid is missing, and its green paper label is water damaged, suggesting that the box fell victim to a leaking roof or a burst pipe. Worst of all, one of the longer walls is cracked down the middle, and one half of this wall is nearly detached from the floor of the box. Under the supervision of Laura McCann, Conservation Librarian, I designed a preservation enclosure for the Daguerreotype plates and their wooden box. Again, we decided to preserve these 25 objects in their current states, rather than trying to repair their damage.

Our decision to not perform conservation treatments on these objects was motivated by several factors: the tarnish on the silver plates tells an interesting story, and polishing the silver would not only change that story, it would necessitate the removal of some original material. And what would be accomplished by removing the tarnish, other than obscuring historical evidence? It's unreasonable to expect 150 years old plates to look "new!" Similarly, the wooden box has a broken wall, but what would be accomplished by gluing it back together? The box still wouldn't be strong enough to protect the Daguerreotype plates on its own, and, of course, its lid is still missing. Lastly, there are always more projects flowing into the lab, so why waste time by over-treating a stable object? Better to protect what already exists.

I began by enclosing each of the Daguerreotype plates in a 4-flap paper wrapper to protect the metal surfaces from abrasion and from further exposure to pollutants (Photos 4-5). The paper that I chose is unbuffered, and it passes the “PAT,” or Photographic Activity Test. This is important, because materials that are not PAT-passed might chemically interact with photographs and accelerate their degradation. I selected an archival storage container that was large enough to house both the plates and the wooden box, and I had to consider how everything would be stored inside it. Laura decided that it was safer to store the plates vertically (the same way they had been stored in their wooden box), so I created two small trays to hold them upright. I thought it would be best to divide the metal plates into two groups, which would balance their considerable weight inside the new enclosure... if one side of a box is much heavier than the other, an unsuspecting person might drop it!

The two trays (Photo 6) have a hollow, removable insert which keeps the plates upright in storage, but which can be removed for easier access to the plates. I wrapped the exterior of the wooden box in a piece of Mylar (thin, clear polyester film) and I inserted a piece of flexible foam (Volara) in the back compartment, to hold the broken wall upright (Photo 7). The Mylar will protect the delicate paper label from abrasion, and it supports the broken wall from the outside. Finally, I created a carrying tray with cotton straps, so that the wooden box can easily be lifted out of its archival box. The final enclosure (Photo 8) Looks a little intimidating when you first remove the lid, but its primary purpose is to protect the object from further damage in transit or storage:

This treatment was pure “preservation”; unlike the 19th century publisher’s bindings that I treated, no amount of repair would allow this object to safely return to the stacks all by itself. An enclosure was necessary because of the sheer number of loose components in this object, and because the lidless wooden box is no longer capable of protecting its 24 plates. This enclosure will keep everything together and will keep the objects safe and dust-free in storage, while still leaving the door open for future conservation work!

Thanks for reading, and stay tuned for tomorrow’s final Preservation Week 2021 blog post, where I’ll discuss the preservation of a Riot Grrrl’s skateboard (see photo below!)

-Cat Stephens

#PreservationWeek#Preservation#Conservation#Libraries#SpecialCollections#TodayInTheLab#NYU#NYULibraries#AmericanLibraryAssociation#ALA#NYUIFA

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Showing Off Our Showcases

As part of the Fales renovation plans, the conservators in the Barbara Goldsmith Preservation and Conservation Department worked with Charlotte Priddle, Director of NYU Special Collections, to retrofit eight showcases used for the display of art so that they can be used safely with many different kinds of materials.

[Sarah Montonchaikul examining a showcase]

Not all showcases are made equally! The materials used in the construction of cases can do a lot of harm to art and archival objects. Lightweight particle boards like MDF (medium density fiberboard) can emit acidic vapors, and sealants and adhesives will emit volatile organic compounds (VOCs), both of which can damage collection materials. Fales’ showcases had never been taken apart, and were an unknown.

Enter our showcase retrofitting project. Jessica Pace, preventive conservator, and Sarah Montonchaikul, a 2nd year objects conservation student at the Conservation Center (Institute of Fine Arts, NYU), have disassembled all of the showcases and examined the components to figure out how to safeguard the objects that will be displayed within these cases.

[Particle board beneath an unknown textile, glued with an unknown adhesive.]

We have finished covering all of the problematic particle boards with a barrier film to keep acid vapors from leaching out and contaminating the case environments. In the next few weeks, our accelerated aging testing of the new plastic gaskets and sealants will be finished and we can start reassembling the showcases!

13 notes

·

View notes