#one of my personal favourites of marryat's books

Text

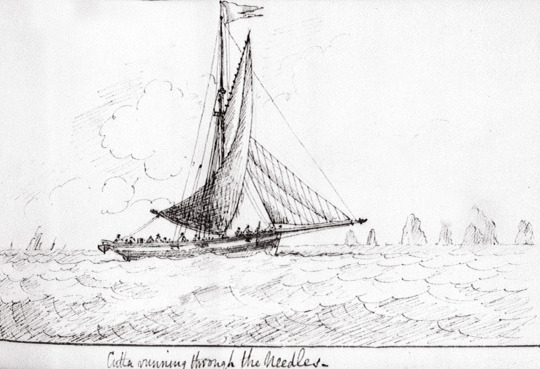

In the meantime, it was dark; the cutter flew along the coast; and the Needles' lights were on the larboard bow. The conversation between Cecilia, Mrs. Lascelles, and her father, was long. When all had been detailed, and the conduct of Pickersgill duly represented, Lord B. acknowledged that, by attacking the smuggler, he had laid himself open to retaliation; that Pickersgill had shewn a great deal of forbearance in every instance; and, after all, had he not gone on board the yacht she might have been lost, with only three seamen on board. He was amused with the smuggling and the fright of his sister; still more, with the gentlemen being sent to Cherbourg; and much consoled that he was not the only one to be laughed at.

— Frederick Marryat, The Three Cutters

Cutter running through the Needles, drawing by Lt. Edward Bamfylde Eagles, circa 1840.

#frederick marryat#captain marryat#age of sail#cutter#the three cutters#the needles#edward bamfylde eagles#naval art#english literature#british literature#one of my personal favourites of marryat's books

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

I just finished Hornblower disc four, and I know there has been some interest in me liveblogging my reactions. I'm worried my takes won't be well-received, even though I'm really enjoying the Hornblower TV series so far, because of my severe Captain Marryat/Frank Mildmay brain worms, and also my hatred of the fan favourite (?) Archie Kennedy.

I thought fans were upset that he gets killed off? I personally can't stand him and he can't get killed off soon enough for me. I'm wondering how much more of this character I have to endure (although it makes me more interested in the books, since at least I know they're Archie-free).

Ioan Gruffudd as Hornblower continues to literally glow with his radiant beauty in almost every scene. It reminds me of those memes about the anime main character, who is the only detailed, vibrant and unique character in a crowd of dull, ordinary people: except it's the most beautiful man on God's green earth, in a crowd of hideous filthy character actors. Like they really stacked this production with the ugliest men they could find, as if young Ioan didn't look pretty enough.

I'm sorry about the swooning, this is definitely not typical for me is all I can say. The fact that Hornblower is a swashbuckling age of sail hero means he almost inevitably has some Frank Mildmay-like moments, besides his curly dark hair and other attributes. Come to think of it, Frank's pretty cold-hearted—maybe this is why I hate lovable sidekicks idk.

I continue to enjoy fictional Pellew and even think he's handsome, but no one is half as gorgeous as Hornblower. He's like Frank Mildmay-tier beauty, except he has that stupid queue and breeches because it's (ugh) the 1790s. [eta: to clarify, I mostly dislike the long hair, and prefer 1810s hats too, breeches are okay if they are with hessian boots or gaiters, don't kill me breeches fandom.] I thrill whenever Hornblower shows some steel and takes command—ohhh Frank Mildmay dreamy sigh—although I always wish this was set in the 1810s. Or at least like, 1806-1814. What good is a new lieutenant if he doesn't have a shiny epaulette to admire in a mirror!

I still enjoy a lot of the costuming, and this is the part of the 18th century that I find most tolerable (the very end of it lol). I remind myself that Newton Forster takes place partly in this time. The production values feel overall better as the series goes on, and I really loved all the Napoleonic combat scenes and the redcoats. I appreciate that the douchy Earl of Edrington is a balanced character who is actually a competent soldier and leader. (Too bad his nice wavy hair couldn't be in a short early 19th century style, sigh.)

Captain Marryat, Navy guy that he was, took every opportunity to dunk on soldiers and said things like they never read books, and hate long sea voyages because of it. I feel like Marryat might actually have less evil French and Spanish characters? Not sure, and I'll evaluate Forester separately from the TV adaptation.

#shaun talks#shaun watches hornblower#please don't kill me#i also feel like frank mildmay has female characters with more depth#even though it has some godawful ones like martyr doormat eugenia

18 notes

·

View notes

Note

Could you recommend me some good novels about England under the Stuarts? Which ones are in your opinion the best to read and why? Thanks Empress :)

There are A LOT that I’ve enjoyed but I think I’ll list my favourites so the list isn’t incredibly long. I’d suggest all these novels:

The Darling Strumpet by Gillian Bagwell - This is about Nell Gwynn. It’s really gritty and vivid, Bagwell obviously did a lot of research into what Restoration England looked like, smelled like, sounded like and tasted like.

Forever Amber by Kathleen Windsor - Kind of a classic, really. It’s about Amber St. Clare (not based on an irl person) who works her way up the ranks of Restoration society through sex and marriage. She becomes an actress, too.

The Illumination of Ursula Flight by Anna Marie Crowhurst - Ursula Flight (not based on an irl person, though has an air of Aphra Behn about her), born at the cusp of England’s Restoration era in the late 17th century, wants to become a playwright and a libertine, but her genteel family have other ideas.

The Baroque Cycle by Neal Stephenson - It’s hard to describe this series because it’s an alternate history/science fiction series set in the Restoration and early 18th century Europe. Stephenson also didn’t publish it as trilogy, but rather, as volumes. I think my favourite volume is Quicksilver (which is the first volume).

The Children of the New Forest by Captain Marryat - This is a classic children’s book from the 19th century. It is set during the English Civil War. The children of the aristocratic Beverly family have their house destroyed by Roundheads and are orphaned so they find refuge with the forest keeper who tries to keep them safe from hostile Roundheads and raise them as foresters. They do meet some sympathetic Puritans so it’s not completely one sided, and they end up saving and befriending a Spanish Rromani boy named Pablo. They also help young Charles II escape to the continent near the end of the book.

The Countess and the King by Susan Holloway Scott - Scott has written several historical fictions set in this era (a book about Louise de Kerouaille, a book about Barbara Villiers, a book about Sarah Churchill etc.) but this is my favourite: it’s about the life of Catherine Sedley, daughter of the rake, Charles Sedley, who eventually went on to become the mistress of Charles II’s brother, the Duke of York (later James II). Catherine wasn’t considered beautiful but she was considered incredibly funny, which this book showcases, and I also think this book does a good job of showing the gradually deteriorating friendship between Catherine and the Duke of York’s young wife, Mary of Modena.

The Ashes of London by Andrew Taylor - This has been critically acclaimed recently: it’s a murder mystery/historical thriller that takes place just after the Great Fire of London has devastated the city. It is so vivid. There are actually a few murder mystery books set in Stuart London!

As Meat Loves Salt by Maria McCann - Two soldiers fall in love amongst the wreckage and devastation of the Civil War. Really beautiful but sad.

Lady on the Coin by Margaret Campbell Barnes - Not to be confused with 'The Girl on the Coin,’ this is the story of Frances Stewart, who famously and consistently refused to be Charles II’s mistress but did choose to elope with the Duke of Richmond and Lennox instead. Lennox is so sexy in this book….he’s very “troubled genius” and likes to drink a little too much.

The King’s Touch by Jude Morgan - the story of Charles II’s Restoration and reign told from the perspective of his illegitimate son, the Duke of Monmouth. LOVED this one.

Cavalier Queen by Fiona Mountain - Okay, so this is like......kind of inaccurate since it plays up a romance between Queen Henrietta Maria, Charles I’s queen consort, and Henry Jermyn, Earl of St Albans (which was rumoured to slander her but probably never happened). It is a very good novel about Henrietta Maria’s marriage to Charles I, her life during his reign and her experiences during the ECW and his eventual execution though. I really do like it, and....Jermyn is sexy, I Won’t Lie.

The Silent Companions by Laura Purcell - Whilst this book flits between both the mid 19th century and the early 17th century, I wanted to recommend it because it is so damn scary. Such a good gothic horror novel. A newly widowed London wife, used to bustling and glamorous living, has been left her husband’s family estate. Surprise surprise, it’s a dilapidated manor house with an eerie air. And worse still, it seems to be plagued by a collection of 17th century wooden painted figures that hold a dark and terrible secret.

I’m also going to check out Jean Plaidy’s Stuart (and Georgian) series soon. She’s written loads of books about various female figures from the Stuart era, including some stuff set in the reign of Queen Anne. I’ve heard she’s a brilliant writer.

63 notes

·

View notes

Note

In your opinion, what are the 3 best books written by Marryat? I should like to try a few...thank you for your time!

A good question! My feelings are conflicted, because there are Marryat books that I adore (such as The King’s Own) that are messy disasters on multiple levels. Is this about personal favourites, or literary merit? Even the question of literary merit is debatable, because Marryat can be a compelling storyteller, especially when he’s writing from his lived experiences in the early 19th century Royal Navy, but he was never a polished writer. (And this isn’t even getting into his period-typical prejudices that can be pretty shocking to a 21st century reader: fair warning for bigoted language and use of offensive stereotypes in his books).

Frank Mildmay (The Naval Officer) is my perennial recommendation that is equal parts merit and personal fave. The title character is highly autobiographical—and he’s a complete bastard, a borderline villain protagonist. A cruel, self-centered, yet handsome young officer in Nelson’s navy, he’s clearly damaged and traumatised by his war experiences, but doesn’t hesitate to inflict violence on others. The book is marred by the rushed and shallow redemption arc for the protagonist, but frankly I enjoyed that part too. Frank gets a happy ending, despite his selfish and vicious life.

Jacob Faithful is the book that Marryat himself said was his personal favourite (according to “Captain Marryat at Langham” published 1867 in The Cornhill Magazine). It’s an unusual choice, and not one of his hit titles like Mr. Midshipman Easy or Peter Simple, but I have to agree with Marryat. I think he is drawing on his childhood in London near the River Thames for this novel, but the protagonist is a waterman with none of Marryat’s wealth and privilege. It’s a maritime story (and Jacob is even impressed on a king’s ship at one point), but it’s not a navy/midshipman novel. It has some of Marryat’s best and strongest writing with a Dickensian feel in an appealing rags to riches story.

The Three Cutters, a novella originally bundled with Marryat’s short story The Pirate. Funny, clever, taut story writing that sets a rich’s man yacht, a crew of Channel smugglers, and a rag-tag group of Royal Navy officers in a revenue cutter on a collision course. I have recommended it as a great intro to Marryat without the commitment of his full-length (and rambling) novels.

(N.B. Marryat’s The Pirate is one of his absolute worst stories, in my humble opinion. See also my Quickstart Guide to Reading Marryat.)

If you’re looking for one of Marryat’s midshipman novels specifically, Frank Mildmay is one of them, and I would recommend Percival Keene and Peter Simple ahead of Mr. Midshipman Easy. (Percival Keene is the novel that James Fitzjames quoted in one of his letters, according to William Battersby.) My tag specifically for discussing the experience of reading Captain Marryat’s works is reading marryat.

#asks#reading marryat#frederick marryat#captain marryat#age of sail literature#also feel free to send messages if you want!#book recs#frank mildmay#jacob faithful#the three cutters#honourable mention to non-fiction 'diary in america' which is very underappreciated#thank you for the question!

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm thinking again about Frederick Marryat's amateur artwork, and how much I enjoy this detail from 'Lieutenant Blockhead keeping the Morning Watch'—evidently Blockhead himself, with his spyglass tucked under one arm and a cup of coffee or tea beside him on the capstan. (Drinking coffee on the morning watch is mentioned in The King's Own.) I don't know why there are Roman numerals on the capstan, but I assume this is an authentic touch.

As a visual artist Marryat is crude and lacking in technical skill, but like his writing, his artwork is a fascinating window on his world, and it's obvious that he cares about the small details.

This picture and related drawings date from 1820, when Marryat was still in the service and had yet to fight in the First Anglo-Burmese War. He wouldn't publish his first novel until 1829, so this is an early foray into self-expression: a comic series of prints that George Cruikshank would engrave (taking many liberties to improve on Marryat's rough drawings).

I suspect that there's a lot of Marryat in his character of William Blockhead, from the naughty boy with curly hair to the very well-built officer appreciating his assets in a mirror in Cruikshank's rendering. Florence Marryat threw her support behind this idea in the Life and Letters of her father, writing that "the draughtsman's own caricature figured in another publication called 'The Adventures of Master Blockhead'".

One thing that has always impressed me about Marryat's drawings is the sheer confidence expressed in them. He had to be aware that he wasn't the greatest artist, but he doesn't seem discouraged by it or defensive, in contrast to his salty and clearly hurt reactions to literary critics. Marryat is like the opposite of the cliche amateur artist who poses characters with their hands in their pockets or behind their backs to avoid drawing hands; he's not afraid to tackle any pose for some truly dynamic scenes.

Marryat's son Frank and daughter Augusta were better artists than their father, and both of them illustrated published books. Sometimes I imagine Captain Marryat drawing and painting with his children and encouraging them, since he was known as an affectionate parent who was much more involved with his children than typical upper-class parents of his day. Florence Marryat doesn't mention this scenario with art supplies so it's pure speculation on my part, but it seems likely.

I can't believe that Marryat stopped drawing after his print-making collaboration with George Cruikshank ended, and there's substantial evidence that he did not. My two-volume edition of Peter Simple with Robert W. Buss's engravings and an introductory essay by Michael Sadleir suggests that Marryat may have made sketches that Buss used as a guide for his professional illustrations. There's also an 1841 letter from Marryat reproduced in Life and Letters where he writes of an upcoming book, "I have been amusing myself with drawing all the illustrations myself and they will do very well."

Marryat's artwork documents details that sometimes are not apparent in his novels, like the appearance of convicts' uniforms (contrast with the scene from Peter Simple), or they are too minor to merit a written description but pique my interest—belaying pin racks, baskets and containers on deck for ropes and ammunition, the overcoats worn by sailors in foul weather. For all of their shortcomings, they can be treated like primary sources. Marryat didn't research his compositions, he didn't pore through reference books on sailing ships, he drew and painted from life. From his own memories and experiences.

Marryat is from an era of empire and discovery that encouraged Royal Navy officers to cultivate their skills as artists. Before portable and reliable cameras, it might be an officer sketching a newly catalogued species, a foreign landscape, or an important battle. Marryat produced both humorous nautical scenes and more sober depictions of warfare. Famously, he sketched Napoleon on his deathbed. But my personal favourites are his rough studies full of character and personality, unimproved by a professional artist and engraver.

#frederick marryat#captain marryat#age of sail#marryat's artwork#maritime art#biography#life and letters#naval history#marryat is surprisingly good at drawing clothes#it's that Man of Fashion knowledge he has shining through#marryat family#royal navy

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

My personal knowledge of the 19th century British historian, writer, and public intellectual Thomas Carlyle is limited to an attempt to read Sartor Resartus when I was about 12, for unknown reasons. I was already deep into Victorian weirdness at that age, and somehow I heard of Carlyle and decided to read that of all books. (I don't think I got very far, Carlyle was no Charles Dickens).

But there's an anecdote about Carlyle reading Frederick Marryat that I can't stop thinking about.

When Carlyle's housemaid accidentally burned part of the manuscript he was writing, he dealt with the blow by taking time off, distracting himself by reading favourite authors. (Oliver Warner, Captain Marryat: A Rediscovery p. 192) Carlyle described these books as something like, "Captain Marryat and other trash" in his correspondence.

A modern biography of Thomas Carlyle (Moral Desperado by Simon Heffer) tells it this way:

Instead, Carlyle sought other forms of relief, still reading what he called 'the trashiest heap of novels', including some by Captain Marryat.

On the one hand it's a withering slam of Marryat's literary quality, literally calling him trash; but on the other hand, it makes him look like a very tempting kind of junk food. Even if Marryat isn't very respectable, this leading intellectual admits to indulging in his books for comfort.

I really empathise with Carlyle here—I constantly try to read Serious books about my interests, only to return to re-reading Marryat. (It doesn’t help that my phone is full of Marryat’s writing, a click away at all times).

He was a pioneer of serialised fiction published in magazines (according to Louis J. Parascandola); and his habit of intruding in his narratives with personal anecdotes and opinions can sometimes make Marryat read like cliche fanfiction. (I don't think most fanfic authors are as chatty with the reader or as melodramatic as Captain Marryat). I try to approach Marryat critically, but he’s still a guilty pleasure.

#thomas carlyle#frederick marryat#literature#19th century#british literature#reading marryat#captain marryat#oliver warner#louis j. parascandola

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Phantom Ship, the wrap-up

If it seems like it has been an extraordinarily long time since I have posted a book review here, I’ve been reading The Phantom Ship at a glacial pace. Other books and projects have occupied my time; and one of the perils of tearing through Marryat’s complete works is that I keep wanting to re-read my favourite ones, like Frank Mildmay and Jacob Faithful.

It doesn’t help that The Phantom Ship is a deeply mediocre book. If I had to rate it, I’d give it two-and-a-half stars out of five: don’t read this one unless you’re a Marryat completist or tracking down every version of the Flying Dutchman story. As usual with Captain Marryat, the quality is uneven, and a few moments really shine. One of these is the chapter that contains the story “The White Wolf of the Hartz Mountains,” which is also the first appearance of a female werewolf in Western literature. The monster is brilliantly ghoulish, and one theme that I enjoyed throughout the book is that supernatural beings can mingle unnoticed in human society. Sensitive individuals might find them creepy or foreboding, but they are otherwise unmarked.

Although the Flying Dutchman story feels like an ancient myth, in Frederick Marryat’s lifetime it was a more recent development. Wikipedia credits the first print reference to the story to a book published in 1790— only two years before Marryat was born. Numerous versions of it were published in the early part of the 19th century, or made into popular theatrical productions. I was frankly surprised by how many Flying Dutchman variants were made, many even using the title “The Phantom Ship.”

Marryat published his version of the tale in disjointed installments, first serialised in the New Monthly Magazine in March 1837, then in February 1838, and finally from February to August, 1839. Alan Buster suggests that the hiatus was probably caused by Marryat’s American trip that produced Diary in America (Buster, Captain Marryat: Sea-Officer Novelist Country Squire). It probably didn’t help the cohesiveness of what is already a very derivative story, even if the character of Amine is, as Buster describes her, “Marryat’s most spirited and independent heroine.”

Rather randomly, I came across a competing penny dreadful version of the story that was published in approximately the same year as Marryat’s adaptation.

According to the British Library, this was published circa 1839 by Thomas Peckett Prest (1810–1859), a prolific writer of penny dreadfuls. Marryat is not only a clumsy writer of historical fiction, best at retelling events from his own life and times, he had to compete with a cut-rate version of the Flying Dutchman saga.

If there’s one overarching villian in Marryat’s story, it’s not demon ships or werewolves, it’s the Catholic Church. He takes a forgiving view of pagan sorcery but wicked and corrupt Catholics seem to grow more obnoxious and harmful throughout the narrative, eventually resulting in death and ruin for the main characters. The horrors of the Inquisition in the Portuguese colony of Goa are memorable, and I found myself raging against the unfairness of it all, as much as I’m aware that Marryat is definitely biased.

The colonial practices of the Dutch East India Company are not shown in a favourable light, and it occurred to me that the huge popularity of the Flying Dutchman story in the English-speaking world in this time period could be interpreted as a way of criticizing the abuses of the British Empire. A cursory search shows that there is a lot of scholarly analysis basically saying this exact thing. The doomed Captain Vanderdecken is a figure of imperialist greed, and in some versions of the story that make him irredeemably evil he’s a slave trader.

The plot hook of Vanderdecken’s living son searching for his cursed father to rescue/redeem him seems like it would be ideal for Marryat, who loved to explore troubled father-son relationships, but the opportunity is wasted. We get very little Phantom Ship and a whole lot of meddling priests, Dutch East India Company business, colonial warfare, supernaturally annoying cursed pilots, and a tedious amount of shipwrecks and gales. (Normally when Marryat writes about storms at sea his verisimilitude is compelling, but it happens so often in this book as to be groan-worthy).

Whenever Marryat writes about southeast Asia I have to wonder if he’s drawing from his experiences in the First Anglo-Burmese War, and there are a lot of Indonesian locales in the book including Ternate and Tidore. Malay people use kris daggers in The Phantom Ship (spelled phonetically as ‘creezes’), just like in The King’s Own, and in another bizarre similarity they dip the daggers in “the deadly poison of the pine-apple.” (The King’s Own states that “the creeses of the pirates had been steeped in the juice of the pine-apple, which, when fresh applied, is considered as a deadly poison.”)

Surely Marryat knew that pineapples are edible?! European peoples had been aware of pineapples for centuries before his time, and eating them too. Looking into this poison pineapple story, the most I could find was an 1899 book by Rounsevelle Wildman, Tales of the Malayan Coast, from Penang to the Philippines. Wildman describes a process of creating poison kris daggers that involves pineapple juice, but the pineapple juice is not the poisonous agent (that would be arsenic dissolved in lime water). I can only assume that Marryat heard some tale about forging a kris, and due to poor translation or another misunderstanding, he came away with the impression that pineapple juice is deadly. (This still doesn’t explain how he reconciled this knowledge with people eating the fruit).

Marryat is no long-hauler like Charles Dickens, and he can only get so many hundreds of pages into a story before you can almost viscerally feel him getting bored with it. He was obviously eager for The Phantom Ship to end, and not going to expend any more energy giving the characters a more peaceful and happy conclusion. His next novel, Poor Jack, is one of his best, which makes The Phantom Ship feel even more like a half-hearted attempt to cash in on a trend in Flying Dutchman stories while Marryat was preoccupied with travel writing and personal affairs (like his legal separation from his wife, which was also finalized in 1839).

#frederick marryat#captain marryat#the phantom ship#the flying dutchman#19th century literature#book review#reading marryat#amine deserved better#the poison pineapple saga continues

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

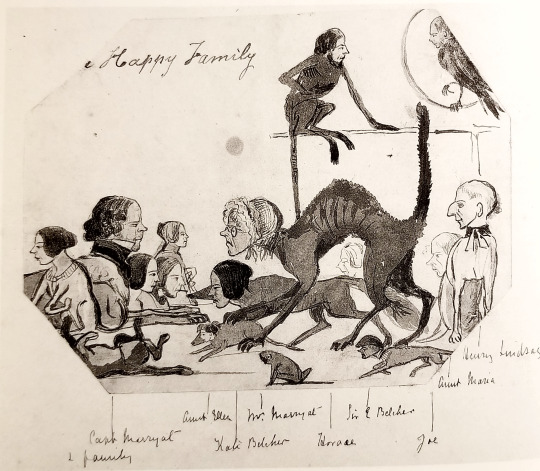

The Marryats: a "Happy Family"

The naval historian Tom Pocock's biography of Frederick Marryat, Captain Marryat: Seaman, Writer and Adventurer, draws heavily on previous works (especially Oliver Warner's Captain Marryat: A Rediscovery) and does not reveal much new information. The charm is mostly in the way Pocock weaves together old material.

Perhaps the most interesting part of his book is the inclusion of this previously unpublished drawing by Frank (Samuel Francis) Marryat, one of Captain Marryat's many children. It’s an anthropomorphic caricature of the Marryat brood, and the centerpiece is Frederick Marryat vs. his wife Kate Marryat. Marryat is drawn as a dog, and his wife is an angry cat with her back arched for an obvious “fighting like cats and dogs” joke that gives Frank’s title a snarky edge.

This is hardly a flattering image of Frederick Marryat (even if he’s still sporting a magnificent cravat in his canine form), but it reveals many things — from Marryat’s appearance as a fifty-something man in the 1840s to the company he was keeping in his home.

Florence Marryat wrote of her father, “As a young man, dark crisp curls covered his head; but later in life, when, having exchanged the sword for the pen and the ploughshare, he affected a soberer and more patriarchal style of dress and manner, he wore his grey hair long, and almost down to his shoulders.” (The Life and Letters of Captain Frederick Marryat) This “long hair” is actually a fairly typical 1840s male style; I want to say that decade had some of the longest hair on men in the 19th century.

Then there is the tantalizing glimpse of the Marryat home that was published anonymously in The Cornhill Magazine in 1867 (Pocock plausibly suggests an old friend of Marryat’s, fellow Royal Navy captain and novelist Frederick Chamier, as the author). This article, “Captain Marryat at Langham,” was clearly referenced by Florence Marryat, who was only 15 years old when her father died. Visiting the Marryat home at Langham, Norfolk in the 1840s, the writer describes Captain Marryat’s appearance:

At the time I now speak of him he was fifty-two years of age; but looked considerably younger. His face was clean shaved; and his hair so long that it reached almost to his shoulders, curling in light loose locks like those of a woman. It was slightly grey. He was dressed in anything but evening costume on the present occasion, having on a short velveteen shooting-jacket and coloured trousers. I could not help smiling as I glanced at his dress —recalling to my mind what a dandy he had been as a young man.

If you have studied pictures of fashionable English women of the 1840s, their hair is often styled into bunches of curls at the temples, and Marryat indeed has this look. The figures grouped around him, labeled “Capt. Marryat + family” by Frank, are possibly his eldest daughters Blanche (Charlotte Blanche), Augusta, and Emily (Emilia.) The male figure with a cigarillo might be Captain Marryat’s son Frederick, who tragically drowned on HMS Avenger in 1847. His portrait in the National Maritime Museum depicts him with a similar hairstyle (but no beard), and his hair is dark blond. I suspect that Frank Marryat is the monkey.

Aunt Ellen and Aunt Maria are Captain Marryat’s sisters (Aunt Maria’s husband Henry Lindsay also makes it into the picture). Ellen seems to have been a favourite of her brother, from the amount of correspondence that mentions her in Life and Letters, and she helped care for Frederick in his last days (Warner, Captain Marryat). The presence of Mrs. Marryat in this picture is probably more of a wry joke to Frank than anything else. The complete deed of separation for Frederick and his wife is reproduced in Alan Buster’s Captain Marryat: Sea-Officer Novelist Country Squire and it includes very specific language that both husband and wife will leave each other alone and not interfere with each other’s lives.

I’m unclear who is supposed to be “Horace” in the drawing (the bird facing the monkey?), but that’s the name of Frederick Marryat’s youngest sibling. There was an astonishing 26-year age gap between second-born Frederick and Horace, which is a thing that can happen when your parents have fifteen children, but by the 1840s Horace would be a young adult and possibly spending time with his famous brother.

The balding man next to Henry Lindsay is labeled “Joe” —could this be Joseph Marryat II?! He appears to have a snub-nosed profile similar to Frederick. There was no love lost between Joseph and Frederick, going by the number of times hated older brothers are killed off in Marryat’s novels, but this “Happy Family” tableau obviously includes an antagonist.

Most amusing to me is the scurrying little dog wearing a cocked hat:

That’s Sir Edward Belcher, most famous for leading the huge Admiralty expedition with a squadron of ships in search of the lost Franklin expedition, and Frederick Marryat’s first cousin. Belcher was close to Frederick, and there’s an anecdote in Robert McCormick’s memoirs about meeting Belcher and Marryat together on shore, at the time Belcher was HMS Terror’s commander in 1836. (Thanks to @handfuloftime for bringing that to my attention!) The “Kate Belcher” dog may be his sister Catherine, who married Frederick Marryat’s brother Charles.

Between Frederick Marryat being depicted as a dog by his son, and his receiving the title “Great Water Dog” from a Burmese leader in the First Anglo-Burmese War (”which pleased his simple tastes,” according to Warner), I think it’s possible to conclude that his fursona was a dog that he struck others as having a dog-like nature. He was, in fact, a dog person who loved his spoiled pets. Florence Marryat describes Zinny the King Charles spaniel and Juno the Italian greyhound in Life and Letters: “two very beautiful, but utterly useless, creatures” who are allowed to scamper over Captain Marryat’s papers and flop around without much rebuke.

#frederick marryat#captain marryat#sir edward belcher#marryat family#1840s#portrait#biography#frank marryat#florence marryat#tom pocock#oliver warner#alan buster#life and letters#captain marryat at langham

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

I want to do a Dr. Macallan vs. Dr. Maturin comparison, but WHOOPS I only know Stephen Maturin’s characterization from the Master and Commander movie (and here’s a gif of Paul Bettany looking aghast at my ignorance.)

Obviously Maturin is the more developed and fully realized character: he plays a major role in 20 novels by Patrick O'Brian (and one unfinished novel.) Whereas the good Doctor “Marryat is bad at giving his characters first names” Macallan plays a part in one of Captain Marryat’s roughest works, The King’s Own. (Protip: if you are still messed up over the death of your 7-year-old son, DO NOT try to make him the main character of your next book.)

Here’s Macallan’s introduction:

The surgeon, whose name was Macallan, was also most deservedly a great favourite with Captain M_____; indeed there was a friendship between them, grown out of long acquaintance with each other’s worth, inconsistent with, and unusual, in a service where the almost despotic power of the superior renders the intimacy of the inferior similar to smoothing with your hand the paw of the lion, whose fangs, in a moment of caprice, may be darted into your flesh. He was a slight, spare man, of about thirty-five years of age, and had graduated and received his diploma at Edinburgh, —an unusual circumstance at that period, although the education in the service was so defective that the medical officers were generally the best informed in the ship. But he was more than the above; he was a naturalist, a man of profound research, and well informed upon most points—of an amiable and gentle disposition, and a sincere Christian.

Doctor Macallan’s friend and confidant, the suspiciously named “Captain M_____,” can only be described as a hybrid of Lord Cochrane and Frederick Marryat. There’s a lot of Cochrane in him, like all of Marryat’s “good” captains, but he shares a number of biographical details and traits with Marryat and takes on a fatherly role to the character based on Marryat’s own son. (Which brings up the thought: if Maturin owes something to Macallan, is there a little bit of Captain Marryat along with the Cochrane in Jack Aubrey?)

When Master and Commander travels to the Galápagos Islands, to the delight of the naturalist Maturin, I felt that it was a way of evoking Darwin’s famous voyage of decades later in the minds of the audience. It has the effect of making Maturin seem ahead of his time, a proto-Darwin, without actually depicting anything anachronistic on screen. Macallan, in contrast, has a few beliefs that are literally antediluvian. While lecturing a young charge on natural history he waxes poetic on unchanging rocks and mountains that have stood “since the creation of the world […] fixed by the Almighty architect, to remain till time shall be no more” and adds that the seas cover the ruins of a wicked former world thanks to the Biblical flood. (So much for plate tectonics.)

Marryat, himself a naturalist who named a genus of sea snails, takes care to further limit Macallan’s knowledge to the very early 19th century. When Macallan describes Ianthina fragilis as the only species of its type to live on the open ocean, Marryat adds in a footnote: “I am aware that there are two or three other pelagic shells, but, at the time of this narrative, they were not known.”

I was reminded constantly of Paul Bettany’s performance as Stephen Maturin in Dr. Macallan’s mannerisms and personality. Pompous and verbose, Macallan loves to infodump to uneducated and skeptical sailors (who take issue with Macallan’s description of coral as an animal), he demands detours to collect animal and mineral specimens, and he gets into a few physical scrapes to comic effect. Macallan slips on seaweed and falls into the ocean while passionately rhapsodizing on the glory of the natural world, and later, “absorbed in his scientific pursuits,” he unwisely dismounts from an elephant by sliding down the animal’s side—"he succeeded in reaching the ground, not exactly on his feet."

#master and commander#stephen maturin#patrick o'brian#captain marryat#the king's own#macallan#age of sail#frederick marryat#lord cochrane

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

I picked up a circa 1970s-1980s Heron Books edition of Mr. Midshipman Easy. From the publisher's "Literary Heritage Collection," it looks like a reproduction of a late 19th century edition and has drawings by Fred Pegram.

The introduction by Christopher Lloyd has an eye-opening passage that underlines just how rapidly Captain Marryat cranked out his novels:

Mr. Midshipman Easy was published in 1836, soon after Marryat's masterpiece, Peter Simple, had appeared. He wrote two other novels that year, as well as editing the Metropolitan Magazine, in which part of the book appeared. As a naval officer in retirement with expensive tastes and a large family, he was constantly in need of money. [....] But the extraordinary speed at which Easy was written was due to a pressing need for money while travelling on the Continent to escape his creditors. Writing from Switzerland to his friend Howard he says: “This is Tuesday night—I began Mid. Easy on Friday morning. This is the 12th day and now that I write I have just this moment finished the first two volumes (and good ones too). Record it and read these two volumes which are the best I ever wrote. Midshipman Easy is my favourite and I shall rattle off the last volume in another six days. I vow that I will finish that book if I live and do well in 18 days. Just to be able to say so.”

Lloyd goes on to add that “Such speed of composition suggests that he did not take the craft of fiction very seriously” although he praises the “fluency and gusto” of Mr. Midshipman Easy. It’s a book that I personally love despite a whole lot of Problematic™ content that even this staid, classic edition has to acknowledge; mentioning that the anti-equality sentiment has not aged well in the introduction.

The part about Marryat traveling to continental Europe to escape debts makes me think of a line from his earlier novel Frank Mildmay: “A tailor’s bill you may avoid by crossing the channel; but the duns of conscience follow you to the antipodes.” I suspected that was an instance of the notably well-dressed Marryat speaking through Mildmay, and it looks like my assumption was correct.

#frederick marryat#captain marryat#mr. midshipman easy#19th century literature#sea stories#marryat wrote a 350-page novel in 18 days!!! 18 days!!!!#'just to be able to say so' what an icon#reading marryat

4 notes

·

View notes