#oneg fear

Text

im finallly gonna get my room cleaned up and my mom said shell help,,

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

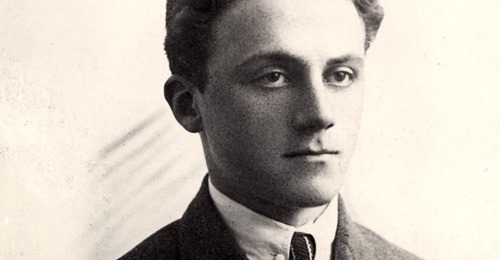

Historian of the Ghetto

“Let the world read and know”

Emanuel Ringelblum, the “historian of the Warsaw ghetto,” compiled an extensive archive of documents depicting the everyday life of the ghetto’s doomed inhabitants. The Ringelbaum Archive is the most important eyewitness accounting of the Holocaust to survive the war.

Born in Buczacz, Poland (now Ukraine) in 1900, Emanuel was a bright child and a top student. His native language was Yiddish and although he learned several other languages, he had a special affection for his native tongue and a lifelong interest in Yiddish literature and theater. Emanuel attended Warsaw University, where he studied history, completing his doctoral thesis in 1927 on the Jews of Warsaw during the Middle Ages.

Emanuel worked as a history teacher in multiple Jewish high schools and in 1923 he co-founded the Young Historians Circle, an influential organization that brought together Jewish history teachers and students to advocate for Jewish causes. Two years later he joined YIVO, the preeminent organization for the study and preservation of Jewish European culture. Emanuel published 126 scholarly articles and was recognized as the world’s foremost expert in the history of the Jews of Europe.

As the Nazis rose to power in the early 1930’s, Emanuel started working with international Jewish relief organizations to help refugees by collecting and distributing funds, as well as providing emotional support. The American Joint Distribution Fund sent him to Zbaszyn, a Polish town near the German border where 6000 Jewish refugees from Germany were being held. Germany had expelled them and Poland didn’t want them so the Jews were stateless. Emanuel spent five weeks there, passing up his own opportunity to escape from Europe so that he could help his suffering Jewish brothers and sisters.

When Germany invaded Poland in 1939, Emanuel described it as “a wave of evil rolled over the whole city.” He became the leader of Aleynilf (Self Help), a group that provided Jews with tools to survive in an increasingly hostile environment. In 1940, Emanuel and his family – his wife Yehudit and small son Uri – were forced into a squalid ghetto, along with all the other Jewish inhabitants of Warsaw. Every city with a Jewish population soon had its own ghetto.

As the days, weeks, and months passed, conditions grew steadily worse. Emanuel wrote, “No day was like the preceding. Images succeeded one another with cinematic speed.” The necessities of life became increasingly scarce – running water, electricity, medical supplies and most critically of all, food. Every day people died of starvation or illness, and there was no way to bury them. Rotting bodies, many of them children, lay in the street.

Emanuel decided to write about life in the ghetto. It was the most important story he would ever tell. He encouraged other inhabitants to write their own testimonies, recording history as it happened. During the day Emanuel wandered the ghetto collecting information, stories and data, and he wrote at night. Emanuel defined the mission: “It must all be recorded with not a single fact omitted. And when the time comes – as it surely will – let the world read and know what the murderers have done.” He knew that the archive would likely be the only testimony about what had happened to the Jews of Poland. It was especially important for him to preserve documents in Yiddish as he feared there would be nobody left to speak his beloved native tongue.

Contributors included writers, rabbis, teachers, social workers, artists, children, and Jews of all ages and backgrounds. They knew they were doomed and the pain was even sharper because all their friends and family were also doomed – leaving nobody behind to remember them. Emanuel’s project was a chance to not be forgotten. The material submitted included essays, diaries, letters, drawings, poetry, music, stories, dark humor, recipes and more. It was an extensive chronicle of ghetto life.

The archive was called Oneg Shabbos – “Pleasure of Shabbat” – because the contributors met on Saturdays to share their writings and discuss their progress. Journalistic ethics were important to Emanuel. “Many-sidedness was the main principle of our work. Objectivity was our other guiding principle. We aspired to reveal the whole truth, as bitter as it may be.” The Oneg Shabbos documents were kept in large milk jars and buried in three different places.

The first document was a poem by Wladyslaw Szlengel called “Telephone” about his apartment building’s last working phone. “With my heart broken and sick/ I think: let me ring/someone on the other side…/and suddenly I realize: my God there/is actually no one to call….”

Hunger was ever-present in the ghetto, and a common theme in the documents is the desperate yearning for food. Leyb Goldin wrote, “It’s you and your stomach. It’s your stomach and you. It’s 90 percent your stomach and a little bit you… Each day the profiles of our children, of our wives, acquire the mourning look of foxes, dingoes, kangaroos. Our howls are like the cry of jackals…The world’s turning upside down. A planet melts in tears. And I – I am hungry, hungry. I am hungry.” (August 1941)

“What we were unable to cry out and shriek to the world, we buried in the ground.” – David Graber, 19

“Sometimes I worry that these terrible pictures of the life we are looking at every day will die with us, like pictures of a panic on a sinking ship. So, let the witness be our writing.” – Rachel Auerbach

“I do not ask for any thanks, for any memorial, for any praise. I only wish to be remembered. I wish my wife to be remembered, Gele Seksztajn. I wish my little daughter to be remembered. Margalit is 20 months old today.” – Israel Lichtenstein

The Oneg Shabbos archive ended in 1943, when the ghetto was liquidated and its inhabitants sent to the gas chambers of Treblinka. Emanuel, his wife Yehudit and son Uri managed to escape before the deportations started and went into hiding. However, in March 1944 their hiding place was discovered. The family was forced outside at gunpoint and executed.

Only three of the 60+ contributors to the Oneg Shabbos archive survived the war. Rachel Auerbach led the search for the buried archive, and her team was able to discover two of the caches, which became known as the Dead Sea Scrolls of the ghetto. The third cache has never been found.

For making sure the murdered Jews of Warsaw would not be forgotten, we honor Emanuel Ringelblum as this week’s Thursday Hero.

Explore the Ringelblum Archive

22 notes

·

View notes

Link

My grandmother Shulamith often gave me walking directions to her childhood home in Warsaw, which was destroyed by the Nazis many years before I was born.

“We lived two buildings down from the Jewish community center and across the street from the Tachkemoni [Rabbinical Seminary],” she would say.

...She spoke as if the pre-World War II city of Warsaw with its cobbled streets still existed. As if I might, like some fictional time traveler, return to the brownstone apartment building at Ulica Grazybowska 22 where she had lived with her parents and four siblings.

Intellectually, particularly as a teacher of the Holocaust, my grandmother knew quite well, of course that her building, indeed most of her street and the city itself had been leveled during World War II.

But until her death in 2009 in Jerusalem, she refused to return to Warsaw, fearing the city, which lived in her mind’s eye, would evaporate, like a ghost in daylight, dispelled by the reality of a new modern Warsaw almost devoid of Jews.

The Warsaw she knew had a Jewish population of more than 300,000, that comprised 30% of the city’s population. It was the largest center of Jewish life in Europe, and second only to New York.

My grandmother and her family had fled Russia and early Soviet antisemitism, choosing to leave their shtetl of Khaslavichy after two families were murdered in pogroms in 1919. A couple and their child, who survived the first pogrom, fled to her family’s home, where the man collapsed onto their floor in his blood splattered clothes.

The escape from the USSR included a harrowing illegal crossing into Poland. The family hid in the back of a hay wagon as their Russian driver raced his horses across the border, while barking dogs alerted the guards.

On a cold and snowy December day, they arrived at Warsaw’s train station. Looking back, for both my grandmother and her younger sister, Anna, it was the moment they left behind the world of the shtetl and entered the modern world.

Warsaw was a city filled with theaters, libraries and modern shops. It was here in the 1920s that they saw their first talking movies, most notably The Jazz Singer. They flirted with boys, including the ones at the rabbinical seminary across the street.

“We would stare out the window at them, and they would stare back,” my Aunt Anna once described for me. They met the leading Jewish personalities of the day, including Emanuel Ringelblum, who perished in the Holocaust and is famous for organizing the clandestine Oneg Shabbat (“Joy of the Sabbath”) Archive chronicling life in the Warsaw Ghetto.

For my grandmother, however, Ringelblum was a dynamic history teacher for whom she had a school girl’s crush and who helped inspire her to become an educator.

My grandmother loved the way the Sabbath candles flickered in the windows of Jewish homes on Friday nights, and fondly recalled picking up the cholent pot from the neighborhood bakery on Saturday.

The two sisters learned to speak Polish fluently. My grandmother changed her Yiddish name Sheyna to the Polish Sonya. She witnessed the May 12, 1926 coup in which fighting erupted in Warsaw’s streets.

But almost from the start, the two understood they had an unrequited love affair with a city and a country that was virulently antisemitic. Jews were held to be foreigners, even though they had lived in Poland for close to 1,000 years.

Within months of their arrival, there was a famous murder case in which the Polish killer of a Jewish man was acquitted, leaving the Jewish community with the belief that they were unsafe, and justice was unattainable for Jews in Poland’s courts. At the large party held following his acquittal, my grandmother recalled, that he was celebrated for killing Jews.

There were also the lesser incidents in which Jews were harassed and cursed on the streets, including one story in which hoodlums surrounded a Jewish man, forcibly shaved off his beard and cut off his side-locks.

Convinced there was no future for Jews in Poland, my grandmother became an ardent Zionist dreaming of Palestine. She was the only woman on the executive board of her Zionist youth group. When she set sail instead for the United States in 1930, with her family, her friends chided her that she would soon lose her Zionist ideals.

She and I moved to Israel together in 2000. Last week, as I left Israel for Poland on Benjamin Netanyahu’s plane to cover the prime minister’s trip to the Warsaw summit for The Jerusalem Post, I heard her voice in my head.

It was my second trip to the Polish capital. On the first morning of the three-day trip, I typed the address of her apartment building into Waze.

Under a cloudy slightly snowy sky, I stared at the concrete gray apartment building, with a supermarket on the ground floor, that has replaced the brownstone where she lived a century ago. Next door, where the Jewish community center had been, is the Radisson Hotel.

...But even in her worst teenage nightmares, her fear of antisemitism could not have led her to imagine the murder of Poland’s three million Jews in the Holocaust.

Nor, in her wildest most positive dreams, when she imagined a State of Israel, do I think she foresaw a scenario in which her grand-daughter would fly to Poland on an Israeli airline together with an Israeli prime minister, staying just a short walk away from her former home.

She would however, have recognized the debate about the complex nature of Jewish-Polish relations that swirled around Netanyahu’s visit. At issue is Polish cooperation with the Nazis in the killing of Jews and the extent of Polish culpability in World War II.

When the war broke out, my grandmother was safely in the United States and married to my grandfather. On my first visit to Warsaw, a Jewish historian told me that most of the Jewish people or artifacts that survived World War II did so only because they left Warsaw before the war.

...I am alive to write this column: not because my grandmother had insight or foresight into Nazi Germany, but because she understood a decade before the Holocaust how deeply rooted Polish hatred of Jews was, in the city she so loved.

136 notes

·

View notes

Text

every time shootings happen I flash back to how everyone was tense when i came to shul the first time, because my rabbi didn’t get my email saying i was going to be there. The guard more or less shadowing me while i introduced myself to the greeter and then only ignoring me while i stumbled through trying to say “shabbot shalom” and then explain that i was converting and drove down a county or two over.

The second and third time i went to shul and showed up a little late, and the people who didn’t know me-- since there was a gap in attendance-- got tense and only went back to being calm and enjoying the day when they saw me fumbling to keep up and then finally finding the right pages. And getting to know me at the oneg.

I have a clear mental image of the neighbors panicking when i sat outside the shul for hours, waiting for selihot service to start since i didn’t want to drive down in the dark. Hearing the people up on the second floor of the apartment complex next door go “There’s someone outside!” “Is it a member?” “I don’t recognize the car..”

The people walking by and staring me down to make comments about Jews, then the neighbors again going by before calling security on me. To make sure i wasn’t there to start something.

I keep wondering how things got to the point that level of caution is needed. I know it’s always been that way but it’s different to see it. I also suddenly worry over “What if someone makes it past security and does something. What if someone is sitting there addressing the congregation before their bar/bat mitzvah and someone--”

I can’t do it.

I worry so much about my people and the people of color that have this fear every day.

It’s tense and this world needs repaired. Spiritual and tangible ducttape. I just don’t know where to get that much rolling.

blah i’m rambling and anxious

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Divine Tarot: 𝄡 Divines

[Image of 𝄡 ]

Ace - Olosta, former Love Custodian

Symbolised as an image of a sad absence, such as a lonely person, or an incomplete gesture or sculpture.

II - Cassan, Sorrow and Peace Custodian

Symbolised as a human man with long flowing hair, usually partaking in some form of sport.

III - Yohoi, Fear Custodian

Symbolised as a pair of bells, ringing without handlers, in a tower on the horizon.

IV - Truvin, former Stability Custodian

Symbolised as a peaceful countryside vista, a gentle rain on farmlands and distant trees.

V - Barra, Animal Custodian

Symbolised as a sheep in shepherds gear, watching over a flock of wolves.

VI - Rosare, Ocean Custodian

Symbolised as a sailor, dragged into the briny deep, by the beautiful iridescent fish of the ocean.

VII - Ka-Oneg, former Fish Custodian

Symbolised as a great beast, water pouring from it’s mouth, flying through space with a parade of smaller fish following it through the stars.

VIII - Fricci, Microbial Custodian

Symbolised as a sad young figure, crying as they look down at the ruins of M’Garr, with Peku’s tower looming behind them.

IX - Storm Mother, former Tide Custodian

Symbolised as a vacant throne on a lonely rock, as the tides tear ships apart around it.

X - O’rv, Youth Custodian

Symbolised as a smiling figure watching over a flock of orphans as they run through the streets.

Scribe - Bandev, former Justice Custodian

Symbolised as a head, usually a recognisable figure’s head, on a spike.

Sword - Lurtula, former Reptile Custodian

Symbolised as a lizard of some kind sitting and eating another, or some other depiction of cannibalism.

Court - Raba Isi, former Extinction Custodian

Symbolised as a creature of the wild, usually a long dead one, tearing apart some man made creation.

Crown - Isander, Insect Custodian

Symbolised as a jovial worker with an industrial insect, say a bee or an ant, copying his motions in miniature.

0 notes