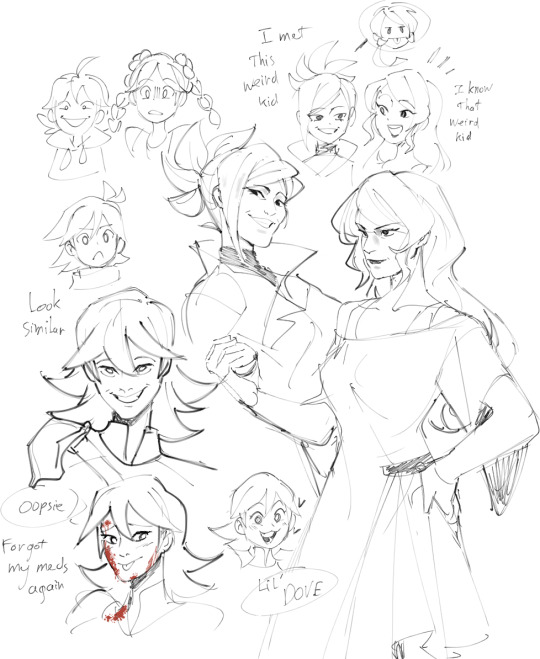

#or just how other manage to befriend Alain

Photo

can you tell that i think about this game a lot

#pokemon#pokemon fangames#pokemon rejuvenation#pokemon rejuv#pkmn rejuvenation#pkmn rejuv#KArts#bless rejuv devs for creating lots of milfs#and they are all part of the Elite#Dylan technically not a dad but i already consider Ana as his daughter#the last 3 comic pages are messy but i'm too lazy to finish them so might as well show them off#this is sorta like...a what if or how i thought the ''A'' gang become closer to each other#or just how other manage to befriend Alain#basically Axel and Crescent was waiting for Aevis to help them with homeworks#but Aevis got stopped by bunch of trainers ''you look like someone that is easy to bully for money''#while waiting. Axel suggest that they look for Alain for help#Crescent was hesitated because she had not talked with Alain much so they seem very scary to her#both end up looking for Alain anyway. who is studying in the same library as them#Axel explained that he once mistaken Alain's pikachu as just another wild shiny pokemon#so when he threw the ball at it. it just end up knocking out the pikachu and he immediately ran off right after Alain appeared#man. i love talking in the tags

105 notes

·

View notes

Link

We lost one of the Great Film Makers yesterday. Her soul will live on In Cinema! Rest In Peace, Agnes! - Phroyd

Agnès Varda, a groundbreaking French filmmaker who was closely associated with the New Wave — although her reimagining of filmmaking conventions actually predated the work of Jean-Luc Godard, François Truffaut and others identified with that movement — died on Friday morning at her home in Paris. She was 90.

Her death, from breast cancer, was confirmed by a spokeswoman for her production company, Ciné-Tamaris.

In recent years, Ms. Varda had focused her directorial skills on nonfiction work that used her life and career as a foundation for philosophical ruminations and visual playfulness. “The Gleaners and I,” a 2000 documentary in which she used the themes of collecting, harvesting and recycling to reflect on her own work, is considered by some to be her masterpiece.

But it was not her last film to receive widespread acclaim. In 2017, at the age of 89, Ms. Varda partnered with the French photographer and muralist known as JR on “Faces Places,” a road movie that featured the two of them roaming rural France, meeting the locals, celebrating them with enormous portraits and forming their own fast friendship. Among its many honors was an Academy Award nomination for best documentary feature. (It did not win, but that year Ms. Varda was given an honorary Academy Award for lifetime achievement.)

It was her early dramatic films that helped establish Ms. Varda as both an emblematic feminist and a cinematic firebrand — among them “Cléo From 5 to 7” (1962), in which a pop singer spends a fretful two hours awaiting the result of a cancer examination, and “Le Bonheur” (1965), about a young husband’s blithely choreographed extramarital affair.

Ms. Varda established herself as a maverick cineaste well before such milestones of the New Wave as Mr. Truffaut’s “The 400 Blows” (1959) and Mr. Godard’s “Breathless” (1960). Her “La Pointe Courte” (1955), which juxtaposed the strife of an unhappy couple with the struggles of a French fishing village, anticipated by several years the narrative and visual rule-breaking of directors like Mr. Truffaut, Mr. Godard and Alain Resnais, who edited “La Pointe Courte” and would introduce Ms. Varda to a number of the New Wave principals in Paris.

These included Mr. Truffaut, Mr. Godard, Claude Chabrol and Éric Rohmer, all of whom had gotten their start at the critic André Bazin’s magazine Cahiers du Cinema, and who became known as the Right Bank group. The more politicized and liberal Left Bank group would come to include Mr. Resnais, Chris Marker and Ms. Varda herself.

Arlette Varda was born on May 30, 1928, in Ixelles, Belgium, the daughter of a Greek father and a French mother. She left Belgium with her family in 1940 for Sète, France, where she spent her teenage years. At 18, she changed her name to Agnès.

She studied art history at the École du Louvre and photography at the École des Beaux-Arts before working as a photographer at the Théâtre National Populaire in Paris.

“I just didn’t see films when I was young,” she said in a 2009 interview. “I was stupid and naïve. Maybe I wouldn’t have made films if I had seen lots of others; maybe it would have stopped me.

“I started totally free and crazy and innocent,” she continued. “Now I’ve seen many films, and many beautiful films. And I try to keep a certain level of quality of my films. I don’t do commercials, I don’t do films pre-prepared by other people, I don’t do star system. So I do my own little thing.”

Her “thing” often involved straddling the line between what was commonly accepted as fiction and nonfiction, and defying the boundaries of gender.

“She was very clear about her feeling that the New Wave was a man’s club and that as a woman it was hard for producers to back her, even after she made ‘Cléo’ in 1962,” T. Jefferson Kline, a professor of French at Boston University and the editor of “Agnès Varda: Interviews” (2013), said in an interview for this obituary. “She obviously was not pleased that as a woman filmmaker she had so much trouble getting produced. She went to Los Angeles with her husband, and she said when she came back to France it was like she didn’t exist.”

Ms. Varda was married to the director Jacques Demy (“Lola,” “The Umbrellas of Cherbourg”) from 1962 until his death in 1990. From 1968 to 1970 they lived in Hollywood, where Mr. Demy made “Model Shop” for Columbia Pictures and Ms. Varda made “Lions Love,” which married a meditative late-’60s Los Angeles aesthetic to the New York counterculture. (The cast included the Warhol “superstar” Viva; Gerome Ragni and James Rado, the writers of the book for the musical “Hair”; and the underground filmmaker Shirley Clarke.) During that same period, she shot the short documentary “Black Panthers” (1968), which included an interview with the incarcerated Panther leader Huey Newton; commissioned by French television, it was suppressed at the time.

It was also during that period that she befriended Jim Morrison, the frontman of the Doors, who visited her and Mr. Demy in France; according to Stephen Davis’s “Jim Morrison: Life, Death, Legend” (2004), she was one of only five mourners at Mr. Morrison’s funeral in the Père Lachaise cemetery in Paris in 1971. That same year she became one of the 343 women to sign the “Manifesto of the 343,” a French petition acknowledging that they had had abortions and thus making themselves vulnerable to prosecution.

In 1972, the birth of her son, Mathieu Demy, now an actor, prompted Ms. Varda to sideline her career. He survives her, as does the costume designer Rosalie Varda Demy, Ms. Varda’s daughter from a previous relationship, who was adopted by Jacques Demy.

“Despite my joy,” Ms. Varda told the actress Mireille Amiel in a 1975 interview, “I couldn’t help resenting the brakes put on my work and my travels.” So she had an electric line of about 300 feet for her camera and microphone run from her house, and with this “umbilical cord” she managed to interview the shopkeepers and her other neighbors on the Rue Daguerre. The result was “Daguerréotypes” (1976).

In 1977 she made what she called her “feminist musical,” and one of her better-known films, “One Sings, the Other Doesn’t,” which also seemed inspired by personal circumstance.

“It’s the story of two 15-year-old girls, their lives and their ideas,” she told Ms. Amiel. “They have to face this key problem: Do they want to have children or not? They each fall in love and encounter the contradictions — work/image, ideas/love, etc.”

One of Ms. Varda’s more controversial films, because of its casting, was “Kung-Fu Master!” (1988), a fictional work about an adult woman — played by the actress Jane Birkin, a friend of Ms. Varda’s — who falls in love with a teenage boy, played by Ms. Varda’s son. The title — it was changed in France to “Le Petit Amour” — referred to the young character’s favorite arcade game. The film was shot more or less simultaneously with “Jane B. par Agnes V.,” another of Ms. Varda’s border crossings between fact and fiction, which she called “an imaginary biopic.”

After Jacques Demy’s death, Ms. Varda made three films as a tribute: the biographical drama “Jacquot de Nantes” (1991) and the documentaries “Les Demoiselles Ont Eu 25 Ans” (1993), about the 25th anniversary of Mr. Demy’s “The Young Girls of Rochefort,” and “L’Univers de Jacques Demy” (1995).

Ms. Varda was then relatively inactive until 1999, when, armed for the first time with a digital camera, she set about making “Les Glaneurs et la Glaneuse” (“The Gleaners and I”), which resurrected an artistic career now well accustomed to under appreciation and resuscitation.

“She was a person of immense talent, but also enormously thoughtful,” said Mr. Kline of Boston University. “When you look at some of the films you might think they were more spontaneous than thought out. A film like ‘Cléo,’ for instance, you might have said, ‘O.K., she just follows Cléo around Paris,’ but the film is extremely beautifully imagined and thought out beforehand.”

In “Vagabond,” an 1985 film in which Sandrine Bonnaire plays a woman who is found dead and whose life is recounted, often in documentary style, “the traveling shots in the film are always ending, and each subsequent shot beginning, on a common visual cue,” Mr. Kline said. “It makes you look at film in a completely different way.”

Alison Smith, author of the critical study “Agnès Varda” (1998), called Ms. Varda “a poet of objects and how we use them.” In an interview for this obituary, she added, “Varda as an artist intrigued, and intrigues, me by the constant freshness and curiosity which she brings to her inquiries into the everyday world and how we relate to it, particularly how she uses the detailed fabric of life.”

Richard Peña, who as director of the New York Film Festival helped introduce “Gleaners” to an American audience, praised that film and Ms. Varda’s “The Beaches of Agnès” (2008) as “touchstones for a new generation of nonfiction filmmakers.”

Ms. Varda is represented at the Museum of Modern Art by photographs, films, videos and a three-screen installation titled “The Triptych of Noirmoutier.” “A decision to change direction and move into installation art when over 80 is, by any standards, remarkable,” Ms. Smith said. “But her energy was awe-inspiring.”

Phroyd

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

How Mari met her Psyduck

A/N: The title says it all. Because of this incident Mari was afraid of water for a long time, but she eventually had to get over it in order to become a water Pokémon trainer. How that happened is a different story.

It was a tradition for the Moreau family to camp by Route 22 near Santalune City during the summer holidays, and this summer was no different. They had made their camp near the river a few days earlier, and now Alain and the 6-year-old Alex were picking up some wood for the campfire somewhere in the forest while Mairin was picking some berries near the tent, occasionally checking what the 8-year-old Mari was doing.

The black-haired, curious girl had taken a liking to water type Pokémon ever since she had befriended the now older Psyduck at Professor Sycamore’s lab. That’s why she was walking by the riverside despite her mother’s orders to not get too close to the water, trying to see any water Pokémon jumping from the river. It was then that she noticed a small abandoned boat tied to a tree, and after quickly looking behind her, knowing her mother would stop her if she saw what she was doing, she untied it, pushed it to the river, and jumped on it.

What Mari hadn’t realized, though, was that the stream was stronger than what she had estimated, and the boat started going downstream so fast that she couldn’t do anything about it. At first she was scared, but being adventurous, she calmed down pretty soon, and watched excitedly as a lot of Goldeen, Magikarp and even a few Carvanha swam past her. For a little while nothing special happened, but suddenly she noticed something weird hanging from a tree branch above the lake.

“Is that a Psyduck?” Mari whispered to herself, confused about its light blue color. However, she soon snapped out of her thoughts because she remembered that Professor Sycamore (or Grandpa, like Mari and Alex sometimes called him) had told her that Psyduck generally weren’t very good swimmers, and the stream seemed to get stronger and stronger... So, that little one was in a great danger.

Mari tried to tell the Pokémon, who seemed to be just a baby, to hold on a little bit longer, but the branch snapped under its weight, and it started falling. The girl was so worried that she automatically grabbed the life-buoy from the boat and jumped after it. Mari managed to catch the Psyduck, but it was only then that she noticed something that made her small heart skip a beat: they were going towards a waterfall so big that they definitely wouldn’t make it if they fell... The only thing she could do was to start yelling and screaming for help as loudly as she could. She closed her eyes and just when she felt she started falling, a vine was wrapped around her wrist.

Mairin’s Chesnaught had found them at the last minute, and pulled them on the solid ground. Mari was in a shock for quite a while, but when she finally recovered enough to move, she first checked if the Duck Pokémon was OK, then wrapped her arms around her mother’s starter Pokémon as a thanks.

“Thank you Chespie. I owe you big time.”

Chespie grunted something that most likely meant: “Like a mother, like a daughter. I always have to save them,” but accepted the girl’s hug nevertheless, even patted her hair a bit with his vines. After all, she had just wanted to save that poor little Pokémon. The group soon heard someone coming towards them and turned to see a very worried red headed woman approaching.

“Mari, how could you? Do you have any idea what could have happened?”

“Y-y-yes,” was all she could get out of her mouth, and she started sobbing uncontrollably. Chespie pointed towards the blue Psyduck with his vines, and Mairin understood that he tried to say Mari had just wanted to save it.

“Oh honey, did you try to save that Psyduck?”

The black haired girl just nodded.

“You are just like your father,” Mairin shook her head, but her expression wasn’t angry but soft and worried now. “I’m sorry, I should have kept a better eye on you. But please, don’t ever run away like that. Your father and I couldn’t handle it if something happened to you... And to think it was so close...”

Mairin hugged her daughter tightly and let her cry the scary experience away. When Mari finally calmed down, the mother and daughter noticed that the Psyduck had joined them, and was now rubbing her head against Mari’s leg.

“Aww, look, she seems to be very thankful to you. I wonder if her family is close...” Mairin looked around but no other Psyduck seemed to be nearby.

“Mama, why is she blue?” Mari asked the question that she had had in her mind since seeing her.

“She is shiny! It is very rare, but sometimes a Pokémon is born with a different color than most of its relatives..”

“So she’s special! Can I keep her, can I, can I, can I?” Mari begged, suddenly forgetting everything about what had just happened.

“We’ll have to try to find her family first, and discuss it with your father. But maybe it’s better if we don’t tell him about this accident...” Mairin added, knowing that Alain wouldn’t let her hear the end of it if he found out about Mari’s adventure. Later that day he got to hear a polished version that Mari had found the Psyduck from a small bond nearby and had fallen - like she was prone to do - in there, which is why her clothes were now drying on the clothesline. Alain had a feeling that it wasn’t the truth, but he didn’t push it, since everything was fine now.

It turned out that the little Psyduck had no family left, so Mari got to keep her, and they became the best friends, but she didn’t dare to go near water in a very long time after the incident.

#marisse#marissonshipping#(sorta. i mean this isn't really about them but they are in it)#my fics#my fankids

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

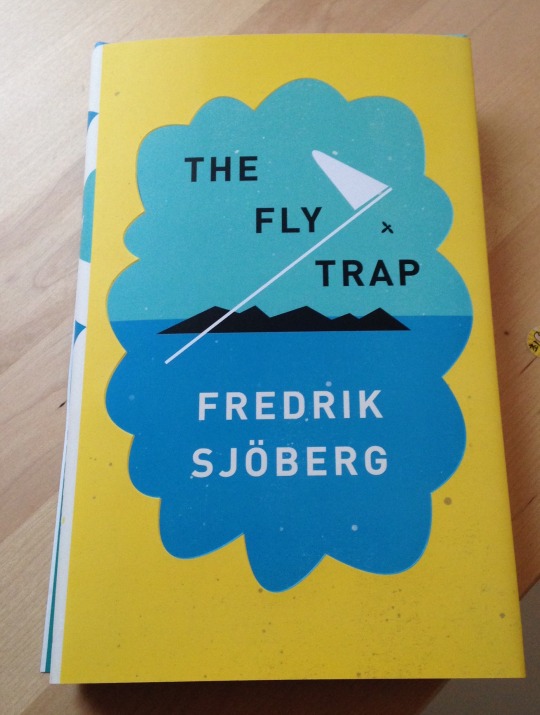

On the Necessity of Limitations and the Joy of Collecting

In the summer of 2015, I took a trip to Hocking Hills, Ohio, a hidden Midwestern treasure. When you show people pictures of the incredible caves and waterfalls, they are understandably skeptical that such a place is found in Ohio. It is a wonderland of natural architecture. And it was here that I had a memorable first encounter. Descending a long staircase near one of the many waterfalls, I saw the people in front of me veer to one side, avoiding something on the wooden railing. The something is pictured above.

To the incredulity of my girlfriend and the others who passed us, I did not hesitate to approach and pick it up. Two large compound eyes, and a set of only two wings: this was not a wasp, but a fly. I sat down to let the creature continue its feast on beads of sweat, and thrilled at the fact that I had found my first hoverfly, a member of the family Syrphidae, a group of fantastic mimics. The humans veering to one side on the stairs were reacting exactly as they “should,” based on the evolutionary tactic of the family. These flies are harmless, and have no way to sting, but mimicry of more dangerous species allows them safety from predators.

I fondly recalled this first hoverfly when reading the first book I finished in 2017, The Fly Trap, by the Swedish entomologist Fredrik Sjöberg, who specializes in these insects. Sjöberg’s book, though—to use a hackneyed phrase—is as much a book about hoverflies as Moby Dick is a book about whaling.

The Fly Trap is a personal memoir, a book by turns charming and heartbreaking. Sjöberg gives us the surface details of his life in such a way that we constantly hear something humming below. To read the book is to attune your senses just a little more to the metaphor and meaning underlying mundane circumstances. At first glance, the book is about a career spent loving and pursuing hoverflies; but underneath all of this, the author pours themes into his book. “Anyway, the hoverflies are only props,” he writes. “No, not only, but to some extent. Here and there, my story is about something else. Exactly what, I don’t know.”

We may each find our own list of themes that move us in the book. There is the theme of aimless travel as a way of trying to tame an overly romantic heart, and how often the author found himself “running away” from entomology, a profession he admits can be lonely, and one which doesn’t often appeal to the ladies. There is the theme of the value of slowness [“A theme granted me by nature. Which is probably just an unjustifiable simplification, a mental wild-goose chase, a poetic paraphrase meant to make a virtue of, or hide, a genetic inability to deal with choice.”]. There is the recurrent theme of how awkward our passions, so clearly vital to our own lives, can seem to others: he relates the embarrassing and often ridiculous encounters with strangers while out chasing and studying hoverflies.

Most significant to me, he composes a thematic ode to limitation. Using the metaphor of islands—for Sjöberg lives and studies his hoverflies on a Swedish isle—he celebrates the things that compress and contain us, thereby giving us the energy to live more fully. Referring to the window of time one has after planning an important trip, but before departure, Sjöberg writes:

“When the days are numbered, everything seems clearer, as if the time between preparation and departure possessed a particular magic. The endless stretch of time on the other side always struck me as evasive and treacherous. But the very limited period between now and then held a liberating peace and quiet. This allotment of time was an island. And the island became, later, a measurable moment. For a long time, this discovery was the only truly unclouded dividend that I took from my travels.”

Sjöberg finds island everywhere. He writes of the “irrepressible urge of curious boys to explore islands, even where islands don’t exist. Or, to be more exact, where islands are not to be discovered without the creative imagination that characterizes artists and good scientists.” It is the mind of an artist and scientist which elevates limitation to an art. While some may want to devote their lives to covering as vast and broad a selection of interests as possible, to drink in as much of the world as one can, the author is praising the study of minutiae, of counting every species of hoverfly, not in the world, but on his Swedish isle. The limitation brings a new glow to what we pursue, in the same way that a greater feeling of accomplishment can come from setting manageable goals, a way to avoid the feeling of being overwhelmed by the immensity of the tasks we have to accomplish.

Sjöberg is a hopeless romantic—and one of the most charming kinds, for instead of constantly laying his heart out for the reader, he flirts with us, only offering glimpses of a tender heart in the midst of longer, staid passages. How many times have I fallen into a mood of hypersensitivity to the emotional life, and wandered into a bookstore at night, where there are pools of light over books whose covers I brush with my fingertips, hoping that some author might befriend me in the way Sjöberg has? Sjöberg, in what seems a similar mood, finds pleasure in pursuing the lives of ordinary people. He chooses in the Fly Trap to focus on the Swedish entomologist who invented the Malaise trap for catching insects: René Edmond Malaise. He confesses a desire to chronicle the lives of underdogs, and in treating Malaise as a heroic figure, his task is similar to Alain de Botton’s narrator in Kiss & Tell: to make an epic of ordinary life, to see metaphor in the actions of another, and to see one’s own life projected onto theirs. This is another way of returning to The Fly Trap’s theme of limitation: to choose not the most famous of culturally significant of figures, but to show the curiosity and strangeness of the life of a forgotten man. Not only does this allow Sjöberg to do much research in an area where biographers aren’t profuse, but it also allows him to dedicate himself more fully to the more limiting constraints of studying a man whose biographical details are more scant. Just look choosing to study something as specific as hoverflies, he chooses to study a specific man’s life. There is sadness and beauty in the way the author follows Malaise through all of the details he uncovers: his ups and downs, his entomological success, his mysterious travels, and even his later crackpot theories about the island of Atlantis. To read Sjöberg’s pursuit of Malaise is almost like reading a detective novel; there is an energy and pace to the uncovering of Malaise’s life, and I forgot more than once that Sjöberg was studying an actual, historical person.

Returning to another theme we’ve talked about in regards to Alain de Botton’s The Romantic Movement, The Fly Trap celebrates the art of collecting. Using the term “buttonology” to refer to the exhaustive collection that someone with this near-manic hobby desires, the author writes: “The idea is to be exhaustive, to include everything. In this way, the buttonologist differs from the mapmaker, whom he resembles and can easily be confused with. But the person who makes maps can never include everything in his picture of reality, which remains a simplification no matter what scale he chooses. Both attempt to capture something and to preserve it. And yet they are very different.” Sjöberg speculates uneasily that perhaps the buttonologist is an erstwhile mapmaker on his way to madness.

The desire to collect exhaustively is present in some minds more than others, but seems to be a somewhat universal human trait. How many hours have been plagued by the anal-retentive desire to perfect a collection? I’ll be more direct: How many hours have I spent poring through my collection of books, hoping to perfect it as a symbolic representation of who I am? How many hours have I spent collecting leaves, as though the trees themselves could not be seen if I did not press their leaves into my notebook? Sjöberg speculates on what motivates collectors and completionists to go to the lengths that they do: “The German-American psychoanalyst Werner Muensterberger has pointed out that many collectors collect to escape the dreadful depressions that constantly pursue them… in a form of fetishism that does indeed allay anxiety.” However, Sjöberg draws a line between artificial and natural objects, and says that natural objects are not fetishes in the same way: “One reason is that they can seldom be purchased for money. In addition, they almost always lack cultural provenance.” To collect leaves, then, is to Sjöberg a healthier obsession, and, we might add, one which also serves to connect us more viscerally to surrounding nature, arguably something every human being needs for a sense of well-being. It’s simply a task of learning when to use the energy of collecting, and when to let go and remind ourselves of a more fundamental sense of being.

In celebrating limitation, in choosing a single biography to focus on, in choosing a single family of insects to study, in choosing to find islands in all of the circumstances of life, Sjöberg is also writing about control. “In exercising control over something, however insignificant and apparently meaningless, there is a peaceful euphoria, however ephemeral and fleeting,” he writes. His book is also about the tension between his sensitive heart and the control he tries to gain over it. Perhaps sensitive and emotionally-driven people are more likely to collect as a means to focusing energy into something constructive (no matter how practically useless the collection, or how futile the goal of collecting exhaustively), a means of curbing excess of heartache and finding purpose, and so positivity.

Finally, there is a sudden, heartrending beauty to many of the passages in The Fly Trap. “Purple loosestrife sways in the light sea breeze. The heavy smell of seaweed. Arctic terns!” exclaims a man in love. Or, in closing, take this heartfelt reverie on the color of maple blossoms in the spring:

“The colour alone puts me in a good mood. Maple blossoms are greenish yellow, and the tender leaves a yellowish green—and not the other way around. From a distance, the mix of these two tones creates a third so beautiful that the language lacks a word to describe it. As we all know, greenery deepens in colour as summer comes on, but the blooming of the maples is when it all begins, when everything is at its brightest and best. Just a week, maybe two, and then the alders burst into lead in deadly earnest. I wish so profoundly that everyone knew. ‘Maples blossoming.’ Those two words on answering machines would be enough. Everyone would get the message. They’d see the colour, sense its nuance, understand. Know then that everything flies, absolutely everything. A thousand commentaries. An entire apparatus of footnotes.”

(Credit to Dana Ocker for the 3rd and 7th images. http://www.domediaart.com )

Sjöberg, Fredrik. The Fly Trap. 2004. Translated by Thomas Zeal, 2014. Vintage Book edition August 2016. Vintage (Penguin Random House LLC), New York. 278 p. $17.00

1 note

·

View note