#pauline trigère

Text

Richard Avedon - Samantha Jones Wearing a Dress by Pauline Trigère (Vogue 1968)

#richard avedon#samantha jones#vogue#photography#fashion photography#vintage fashion#vintage style#vintage#retro#aesthetic#beauty#sixties#60s#60s fashion#60s model#1960s#1960s fashion#swinging sixties#editorial#pauline trigère

579 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gown by Pauline Trigere, 1960s.

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mirella Petteni wearing a shimmering sage green jacket and skirt, over a pale-brown blouse, all covered with paillettes by Pauline Trigère. Photographed by Irving Penn for American Vogue, February 1, 1965.

#mirella petteni#pauline trigère#irving penn#american vogue#vogue#1965#fashion photography#photo shoot#fashion#photography#1960s

63 notes

·

View notes

Text

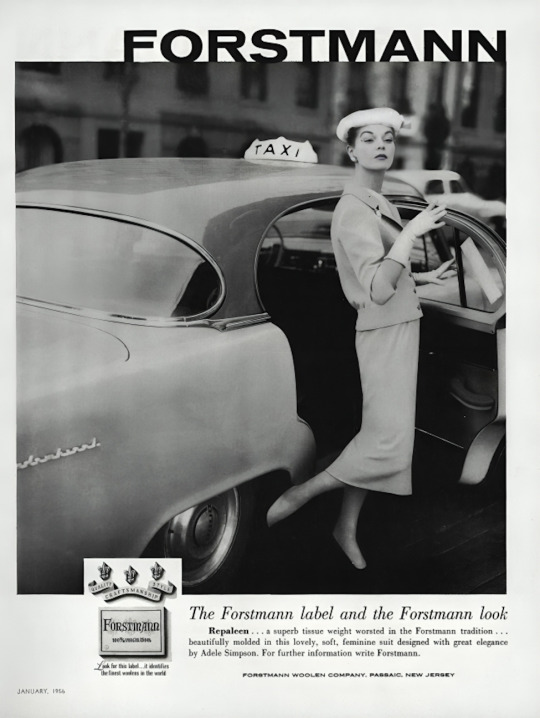

US Vogue January 1956

Top Suzy Parker in a dress and coat set by Pauline Trigère.

Below Jean Patchett in an Adele Simpson suit.

Dessus Suzy Parker dans un ensemble robe et manteau de Pauline Trigère.

En bas Jean Patchett dans un tailleur d'Adele Simpson.

vogue archive

#us vogue#january 1956#fashion 50s#spring/summer#printemps/été#forstmann#pauline trigère#adele simpson#suzy parker#jean patchett#advertising#publicité

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

#veruschka#veruschka von lehndorff#fashion photography#1960s#sixties#franco rubartelli#richard avedon#henry clarke#Irving Penn#bert stern#pauline trigère#yves Saint Laurent#Valentino#Chanel#Vogue#Vogue Italia#supermodel#fashion#60s fashion#DonyaleLuna#Michelangelo Antonioni#Mila schön#ennio morricone#Edda dell’orso

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Return of the cloven-toed mannequin, this time in a frocking fabulous Pauline Trigère dress and stole of black silk and brocade. Fashion history of 1961, from the wardrobe of Gillis MacGil Addison. Via the Museum of the City of New York.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Princess Astrid || Pauline Trigère

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Designing Women

The museum at FIT recently had an exhibit that showcased woman designers and their designs from the 1890s to 1970s. I went to visit this exhibit with no prior knowledge of it, and was immediately excited to see that it was a celebration of women designers. It was even more shocking to find designers in this exhibit that I have taken inspiration from like, Mary Quant and Bonnie Cashin. Other than designers I had already known it was very insightful and fun to find new designers through this exhibit that I really enjoyed, and liked the designs of, like Pauline Fairfax. This exhibit was extremely insightful for me and overall very enjoyable and educational.

To further show and discuss some deigns I wanted to discuss a couple of my favorite designers from this exhibit. I had already known of Mary Quant prior to this exhibit and taken much inspiration from her and her designs, but she was still a favorite for me. In this exhibit. In the exhibit they showcased one of her dresses, a beige, orange and black wool jersey dress. As a dominate designer in the 60s, this dress embodies the designs for teens and young adults in the 60s.

Another designer who was new to me, but I really enjoyed in this exhibit was Pauline Fairfax. In this exhibit she had two dresses on display, both black and made for the house of Hattie Carnegie. I know little of Fairfax or Hattie Carnegie, but in the exhibit it was explained that as a designer of the 40s and 50s she was known as one of the most highly paid female designers in America.

This are a few extra images from the exhibit of designs I liked.

Dress by Louiseboulanger

Dresses by Ann Lowe

Dress by Pauline Trigère

Coat by Bonnie Cashin

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pauline Trigere Dress

Vintage Fashion Guild. "Evening dress, 1960s, Pauline Trigère, c. late 1960s. Bias-cut wool lined with china silk." Instagram, 25 Aug. 2023.https://www.instagram.com/p/CwXlcP-xDgt/.

0 notes

Text

Gianni Penati - Lynn Sutherland Wearing a Dress by Pauline Trigère (Vogue 1970)

#gianni penati#lynn sutherland#vogue#photography#fashion photography#vintage fashion#vintage style#vintage#retro#aesthetic#beauty#seventies#70s#70s fashion#70s style#70s model#1970s#1970s fashion#editorial#pauline trigère

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cocktail dress by Pauline Trigere, late 1950s.

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pauline Trigère - Trigère

Pauline Trigère - Trigère

#PaulineTrigère #Trigère #maisontrigère #creatoredistile #perfettamentechic

Pauline Trigère, è stata una couturière franco-americana fondatrice del brand Trigère.

Gli stili pluripremiata Pauline Trigère raggiunsero l’apice della popolarità negli Stati Uniti negli anni ’50 e ’60. Riconosciuta all’inizio della sua carriera come innovatrice del taglio e della costruzione, Trigère ha portato alle donne di tutte le età di tutto il mondo novità come la tuta, il cappotto senza…

View On WordPress

#Accessori moda#Adele Simpson#Alta moda#Alta moda in Italia#Alta Moda Italiana#Atelier di Alta Moda#Ben Gershal#Brandeis University Archives & Special Collections#Colazione da Tiffany#Cotton Award#Coty Awards#Coty Fashion Hall of Fame#Fashion Critics Award#Fashion Institute of Technology#Franklin Benjamin Elman#Hattie Carnegie#Kent State University Museum Designer Archives#Lazar Radley#Lifetime Achievement Award#Martial et Armand#McCall#Memphis#Neiman-Marcus Award#Patricia Neal#Pauline#Pauline Trigère#PT Concepts#Return Award#Seventh Avenue#tartaruga

0 notes

Photo

Just a Pinch of Prejudice By Laura Shapiro · 4/2/2007

Julia Child became an icon by teaching housewives across the nation that there was more to cooking than gloppy casseroles. But as a new biography reveals, for many years she believed only men—masculine, heterosexual men—could earn the American kitchen respect.

Julia had changed much more than her name when she married in 1946: She changed her very identity, from an individual to half of a couple. She was Julia of Paul and Julia, fundamentally incomplete on her own, one piece of a two-part jigsaw puzzle. And once she became a wife, it was from that perspective that she viewed the world. People belonged in pairs, she felt—male and female together, marching through life as if they were streaming aboard the ark.

For this reason, she found homosexuality outlandish—not immoral, and certainly not to be criminalized, but a rude disruption in the natural order of things. Homophobia was a socially acceptable form of bigotry in midcentury America, and Julia and Paul participated without shame for many years. She often used the term pedal or pedalo—French slang for a homosexual—draping it with condescension, pity, and disapproval. “I had my hair permanented at E. Arden’s, using the same pedalo I had before (I wish all the men in OUR profession in the USA were not pedals!),” she wrote to Simca. Fashion designers were “that little bunch of Pansies,” a cooking school was “a nest of homovipers,” a Boston dinner party was “peopled by 3 fags in an expensive house…. We felt hopelessly square and left when decently possible,” and San Francisco was beautiful but full of pedals—“It appears that SF is their favorite city! I’m tired of them, talented though they are.”

The opposite of homosexual, in her terminology, was “normal” or “well muscled” or “very masculine!” Or, as she often put it, “real male men.” Lesbianism was less of an affront to her, though she felt sorry for women so sexually benumbed that they were not attracted to men. (“Can’t be much fun.”)

For all Julia’s prejudice, however, when she met gay men whose appearance and body language were what she called “normal,” or straight, much of her disapproval evaporated. What she really disliked was effeminacy in men—a caricature that made it clear how they spurned the male-female differences and rituals she so relished. “My, I hate being a widow!” she exclaimed to her close friend Avis DeVoto when Paul was away from home once. “And I have finally had to admit to myself that if I were a real widow, I’d probably have to take to the streets. It’s just no fun; it is not only the physical male, but the mental male. Thank God there are two sexes, is all I can say.”

Julia’s whole being was ignited by proximity to men: They were at the center of her world view, and their presence lent energy, authority, and dignity to all undertakings. The very idea of a social or professional event designed around women was offensive to her. “I hate groups of women,” she said many times, flatly and without apology. No matter the occasion, if it were only for women, she was convinced it would resemble a Helen Hokinson cartoon in the New Yorker: silly clubwomen dithering over their agendas. The only women’s events she approved of were meetings of Le Cercle des Gourmettes, her Paris culinary club, because everyone was busy with the important work of cooking and eating. Otherwise, “Cacklecackle…sounds like a hen house” was her invariable reaction to being in a room full of females. In 1973, she was one of a dozen Women of the Century honored at a lavish dinner, and spent the evening talking with Lillian Hellman, Marya Mannes, Louise Nevelson, and Pauline Trigère, among others. It was very nice, she remarked later, but they should have invited some men. She said the spark was missing.

Not surprisingly, when clubs and restaurants that excluded women came under pressure from feminists to change their policies, Julia sided with the men. “I am very much against the new policy at the Ritz of allowing unaccompanied women into the Grill,” she told an audience at the all-male St. Botolph Club in Boston in 1978, where she had been invited to give a talk. “They’ll turn it into a clacking hen house sure enough, and then no one will want to go there. So, stick to your guns, gentlemen.”

One of Julia’s longtime ambitions was to attract more men to the food world. In France, where cooking had the status of a high art, men were the chief players whether or not they actually cooked: It was their talking, writing, and gourmandizing that put cuisine at the center of domestic and national life. In America, by contrast, cooking was traditionally defined as a female preoccupation, hence unworthy of serious attention. Julia had spent years in France trying to win the respect of male culinary authorities, self-appointed and otherwise, and had met with little success on account of her two handicaps: She was American and she was female.

Yet the experience didn’t turn her into a culinary feminist—quite the opposite. She was inclined to see men the way the French did: natural masters in the kitchen, born with an easy confidence at the stove, graced with an understanding of science and logic that guided them smoothly through the preparation of a meal. No matter that most American men couldn’t cook. An aura of maleness in the world of American cookery would be enough to ennoble the whole enterprise, or so she hoped. When William Rice was appointed food editor of the Washington Post in 1972, she cheered. “I’m all for having MEN in these positions; it immediately lifts it out of the housewifery Dullsville category and into the important things of life!” If improvements were under way in American cooking and eating habits, it had to be men who deserved the credit. “Thank heaven for the men in our TV audience,” she remarked in 1966. “They are responsible for stimulating interest in cooking. The women would just pass it over.”

Women were too easily intimidated in the kitchen, Julia believed; they panicked if the recipe called for three tablespoons of lemon juice and they had only two. Men were fearless—in fact, men were accustomed to bullying, she once noted, which could be a very useful trait in the kitchen.

But while she was confident that men would have a good influence on the American home kitchen, their growing visibility in the culinary profession was a touchier subject. Yes, an infusion of talented male chefs was exactly what the profession needed in order to gain stature and respectability. But the ambitious young men taking up cooking included a number of gays, and Julia feared they would soon define the profession, keeping straight men away. “It is like the ballet filled with homosexuals, so no one else wants to go into it.” She urged a few close friends in the food world to encourage the “de-fagification” of cooking, but admitted that she had no idea how to go about it—and besides, “fags” bought plenty of cookbooks, including hers. “What to do!”

What she did, in the end, was generously support the career aspirations of every gifted cook who came her way—male or female, “normal” or not. Her devotion to “real male men” ran deep, but her appreciation for good cooking ran deeper still, and at this level she was entirely free of prejudice. Richard Olney, the moody American writer living on a Provençal hillside whose expertise in French cooking impressed even the French, was a homosexual and not particularly friendly to Julia or most other people; she, in turn, never took to him personally. Yet she gave a press party when he published Simple French Food in 1974, and used all her contacts to help him promote it, simply because his work was so outstanding.

And although she distanced herself from the women’s movement in general, in her own profession she was a feminist in spite of herself. She simply would not put up with any injustice that threatened to deprive the world of a good chef. Julia funded scholarships for female culinary students, encouraged them to write to her about their progress, did a great deal of networking on behalf of young women chefs, and dispensed quantities of advice and encouragement. For her Master Chefs programs, she made a point of inviting male and female chefs in equal numbers; she worked her media connections tirelessly to help cookbook writers she admired.

Julia’s tangled sensibility about sex, gender, and food relaxed a good deal in the warmth of her friendship with James Beard, whom she loved and admired above anyone else in the American culinary world. Beard, a gay man who neither hid nor flaunted his orientation, was widely recognized as the nation’s leading authority on good cooking when Julia set out on her career. She never forgot how generous he was when she arrived on the scene in 1961, a potential rival whom he greeted enthusiastically and introduced to everybody. “I think he has done much to set the tone of friendliness among cooking types, which is so different from that sniping and backbiting that goes on in France,” Julia told her friend, food writer M. F. K. Fisher. “Jim is such a hard worker, has such a vast store of knowledge in that enormous frame. There is outwardly some bluff in him, but I think that is because he is very tender inside.” She used to say he was “cozy”—one of her favorite qualities in a man. Julia rarely commented on Beard’s homosexuality; she was far more concerned about the various health problems associated with his weight. Yet her homophobia came and went during their long friendship, apparently at random. “Good that people are out of the closet at last!” she noted in her journal in 1974, upon learning that an acquaintance was openly gay. “Makes things easier all around.” A year later, she was agitating to keep “them” out of the culinary business.

But by the 1980s, when the AIDS crisis began to unfold, the horror of what was happening to people she knew, and people she loved, dealt a significant blow to her longtime prejudice. “Last year my husband and I stood by helplessly while a dear and beloved friend went through months of slow and frightening agony,” she told a crowd at the Boston Garden in 1988 during an AIDS benefit sponsored by the American Institute of Wine and Food. “But what of those lonely ones? The ones with no friends or family to ease the slow pain of dying? Those are the people we’re concerned about this evening. And food is of very special importance here. Good food is also love.”

Her politics, her passions, and her fundamental decency were coming together at last. Some time after that, when a woman friend told her she was in love and about to marry another woman, Julia blanched for a second and then congratulated her warmly. What was important was the team.

Reprinted by arrangement with Viking, a member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc., from the forthcoming book Julia Child by Laura Shapiro. Copyright © 2007 by Laura Shapiro.

https://www.bostonmagazine.com/2007/04/02/just-a-pinch-of-prejudice/

0 notes