#perameles gunnii

Text

Loving Pokemon Violet so far!

Miraidon is purple, draconic-looking, probably part Dragon-type, and when you’re riding it on the overworld it controls almost exactly like Spyro from the original Spyro The Dragon trilogy, right down to gliding being activated by pressing ‘jump’ twice in a row!

Now they just need to add a spinny orange legendary based on Perameles gunnii, the Eastern Barred Bandicoot, and it’ll be perfect! XD

0 notes

Photo

Eastern barred bandicoot (Perameles gunnii)

Photo by Ryan Francis

#eastern barred bandicoot#bandicoot#perameles gunnii#perameles#peramelinae#peramelidae#peramelemorphia#australidelphia#marsupialia#metatheria#mammalia#tetrapoda#vertebrata#chordata

115 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Eastern barred bandicoot (Perameles gunnii)

The eastern barred bandicoot is a small, rabbit-sized marsupial native to Tasmania and Victoria, southeastern Australia. The eastern barred bandicoot weighs less than 2 kg and has a short tail and three to four whitish bars across the rump The Eastern barred bandicoot has two separated populations, one on the mainland of Australia and one on the island of Tasmania.

photo credits: JJ Harrison

#eastern barred bandicoot#Perameles gunnii#zoology#biology#biodiversity#science#wildlife#nature#animals#cool critters

171 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Bandicoot

Perameles gunnii

This is a drawing of the eastern barred banicoot.The banicoot is a marsupial meaning that it carries its young in a flesh pouch in its stomach, this of which is actually backwards facing unlike the well known kangaroo and other marsupials, but still have strong hind legs but are rabbit sized.

The second and third toes are fused together of the back hind legs, reduced to being used for only grooming purposes.

The bandicoot has marsupial bones on the pelvis (used to suport the weight of the young) and also has split phalanges (claws or nails) which can only otherwise be seen in other animals that dig and burrow.

Crash Banicoot was a well known video game character and he did so well at highlighting the species that scientists named a fossil of a unknown species in his name.

I chose the Bandicoot, even though they are not the highest on the Cites list and are of least concern, I wanted to draw it as it is a very interesting creature and needs more awareness especially with all the bush fires that have been happening in Australia.I had trouble finding References for this drawing I was lucky to be able to talk to JackDAshby (Twitter) who helped me find some more references from the grant museum.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

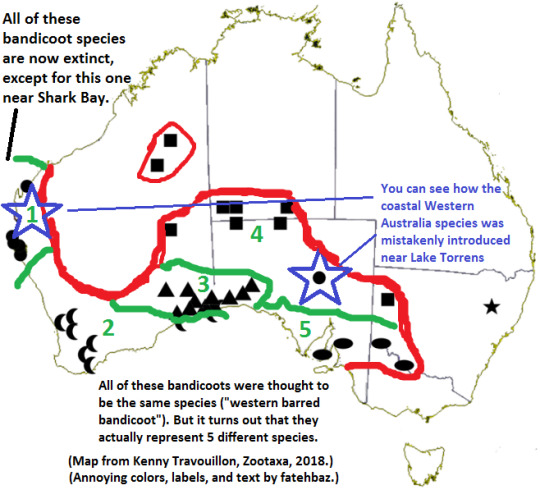

Multiple new cryptic species of bilby, and a case of mistaken identity among bandicoots leading to an accidental introduction:

Even after the catastrophic debacle of introducing non-native cane toads, European rabbits, foxes, dromedary camels, feral cats, and invasive invertebrates, Australian settler institutions are cursed with mistakes which unleash invasive animals even when attempting the well-meaning reintroduction of native species.

Some new research from 2018 revealed an alarming mistake in ecological management. Basically, you’ve got this cute little bilby from the remote far western coast near Shark Bay which was transported by scientists thousands of kilometers and now has a big strong population just chilling near Adelaide. Bilbies, or bandicoots, are understood to be important to maintaining healthy soils, especially in Mediterranean chaparral zone and the other climatically mild and temperate regions of the coast of southern Australia (ranging between Perth through Adelaide to the Melbourne area, and including Tasmania), so there is popular celebration of the reintroduction of bandicoots to environments which they historically inhabited before European agriculture and invasive species led to local extinction of many bandicoots. The western barred bandicoot (Perameles bougainville) went extinct across almost all of its range and disappeared from native habitats on the mainland after European invasion, but a few populations survived on extremely remote islands off the coast of Shark Bay in on the far western coast of Western Australia. Intending to help rehabilitate native soils and plant communities, Australian settler ecologists then took some bandicoots from Shark Bay islands and “reintroduced” the western barred bandicoot over 3000 kilometers away at the Arid Recovery Reserve, near Lake Torrens area north of Adelaide. This was done because settler scientists thought that this bandicoot species had historically lived across much of southern Australia. Uh oh: It turns out that this western barred bandicoot lineage was historically only native to a small portion of the western coast of Australia near Shark Bay far, far away and was never native to the Adelaide or Lake Torrens area, because what was assumed to be the “western barred bandicoot” was actually 5 different cryptic species. 4 of these species are now extinct. The only living member of this bandicoot lineage remains only at Shark Bay. But now, these Shark Bay bandicoots are living north of Adelaide, where a couple thousand of them live at Arid Recovery Reserve.

A western barred bandicoot from the coastal Western Australia population at the islands of Bernier and Dorre:

Kenny Travouillon, the lead researcher who reported the cryptic species and new understanding of bandicoot biodiversity, was featured recently in this report from Western Australian Museum, February 2018:

“For example, many people will have seen the Quenda (Isoodon obesulus fusciventer), a bandicoot familiar to Perth backyards. For more than 150 years the Quenda had been thought to be a subspecies of the Southern Brown Bandicoot (Isoodon obesulus) from the east coast of Australia, when in fact our research shows that it is a distinct species and more closely related to the Golden Bandicoot (Isoodon auratus) endemic to WA and found on Barrow Island and throughout the Kimberley.”

“We also re-evaluated the Western Barred Bandicoot (Perameles bougainville), a species now only found on islands near Shark Bay, and we found that it is in fact a complex of five distinct species. Four of these species had been named in the 1800s, but we described a new species from the Nullarbor region, the Butterfly Bandicoot or Nullarbor Barred Bandicoot (Perameles papillon). This is a new species that went extinct between 1920 and 1960, as a result of feral carnivores spreading west,” he said.

Four of the eight bandicoots that once lived in in WA are now extinct: the Pig-footed Bandicoot (Chaeropus ecaudatus), the Desert Bandicoot (Perameles eremiana), the Marl Bandicoot (Perameles myosuros) and the Butterfly Bandicoot (Perameles papillon). The four that remain are the Quenda (Isoodon fusciventer, previously known as the Southern Brown Bandicoot), Northern Brown Bandicoot (Isoodon macrourus), Golden Bandicoot (Isoodon auratus), and the Little Marl (Perameles bougainville), which was previously known as the Western Barred Bandicoot. [End of excerpt.]

Here’s a story on how the confusion has resulted in a non-native bandicoot species being reintroduced where it didn’t belong:

An endangered Australian bandicoot that was reintroduced to the Australian mainland is now believed to be one of five distinct species, and researchers say it may have been a mistake to introduce it to South Australia.

Scientists working for the Western Australian Museum have published research that concludes that what has been known as the western barred bandicoot is in fact five distinct species – four of which had become extinct by the 1940s as a result of agriculture and introduced predators. The species were closely related but occurred in different parts of Australia.

In the 2000s, western barred bandicoots that had survived on the arid Bernier and Dorre islands off Western Australia were reintroduced to the mainland, including to a predator-proof reserve in outback South Australia. But the new study shows the surviving species that was translocated to that part of the country would never have occurred there previously. Lead researcher Dr Kenny Travouillon made the findings after analysing skulls and DNA from tissue from specimens held in collections in Paris and London.He said the research, which was published in Zootaxa, came to the conclusion that the western barred bandicoot was the only remaining species of the five.

The species that has been reintroduced around Australia would have originally occurred only in parts of Western Australia. “On the mainland, that species should have only been in WA along the coast from Shark Bay to Onslow,” he said. “They should never have been brought to South Australia, but that decision was made from the old research.” Dr Kath Tuft, the general manager of the Arid Recovery Reserve in South Australia, said there were now as many as 2,000 western barred bandicoots at the reserve. She said what had been considered a reintroduction of the species was now technically an introduction. [End of excerpt.]

-----

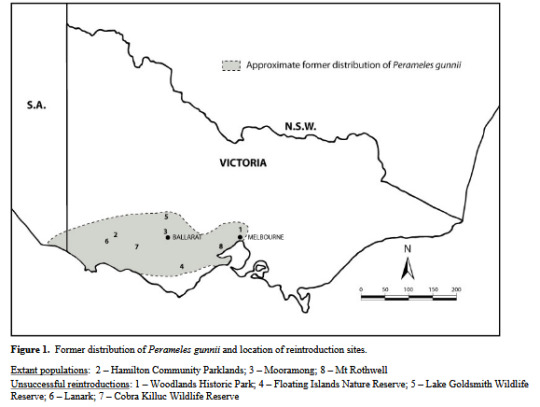

Important distinction: There is another celebrated - and more successful - bandicoot reintroduction project involving a different species.

The eastern barred bandicoot (Perameles gunnii) lives on Tasmania and on the mainland in southern Victoria near Melbourne. The population that once inhabited mainland ecosystems almost went entirely extinct, but there are multiple successful reintroduction sites in Victoria and a captive breeding program.

The species also lives on Tasmania, but here are the reintroduction sites on the mainland near Melbourne [map from the species recovery plan, State Government Victoria]:

This bandicoot species does belong in mainland southern Australia.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Stop everything - it turns out wombats also have biofluorescent fur

https://sciencespies.com/nature/stop-everything-it-turns-out-wombats-also-have-biofluorescent-fur/

Stop everything - it turns out wombats also have biofluorescent fur

First we discovered platypus would look great at a rave, now wombats, bilbies and other marsupials can join the blacklight party – with scientists unexpectedly finding they all glow wonderfully fluorescent greens, blues and pinks beneath UV light.

Over the last few years scientists have found biofluorescence is more common across mammals than we realised – with flying squirrels that glow a bubblegum pink, prompting researchers to see how far back this trait exists in our mammalian heritage by checking out monotremes like the platypus (Ornithorhynchus anatinus) – the most ancient still living mammalian lineage.

Naturally, once the platypus’s glow was revealed, other researchers like Western Australian Museum curator of Mammalogy, Kenny Travouillon and biologist Linette Umbrello, started shining UV down on different specimens in the museum’s collections.

And so far their findings have been far from disappointing, with revelations of neon wombats and bright-eared bilbies.

The glowing wombats are also some of my favourite! #wombat #uv pic.twitter.com/XdgLqAoorX

— Kenny Travouillon (@TravouillonK) November 5, 2020

“We have only tried it on maybe two dozen mammals, so it wasn’t a thorough search.” Travouillon told ScienceAlert. “Probably around a third of them did glow.”

These included platypus (which they double checked), echidna, bandicoots and bilbies, possums and some bats. The Australian creatures join a host of other living things that biofluoresce, including insects, frogs, fish and fungi.

Biofluorescence occurs when a living thing absorbs high energy radiation such as ultraviolet and then emits light back out at a lower frequency. Many proteins have been identified that can do this in skin or in other animal tissues – including bones and teeth, Australian Museum wildlife forensic scientist Greta Frankham explained to ScienceAlert.

“There are chemical compounds in lots of different animal body parts that do seem to fluoresce, so it’s not surprising to find there may be other chemical compounds in other things like fur that fluoresce,” Frankham said.

Scientists have isolated some of these molecules and used them for scientific imaging, like the jellyfish’s green fluorescent protein.

The exact details of how and why biofluorescence occurs in these mammals is still to be determined. But however it’s achieved, it certainly produces some startlingly bright results under UV light, like the ears and tail of this Bilby (Macrotis leucura).

After platypus was shown to glow under UV light, couldn’t resist trying bilbies… their ears and tails shine bright like a diamond! #bilby #uv pic.twitter.com/wL82RDdFYb

— Kenny Travouillon (@TravouillonK) November 3, 2020

Bilbies are a nocturnal and endangered desert dwelling species that happens to like eating another animal that glows under UV – scorpions.

Well this is cool. After all that fuss about the fluorescent platypuses I checked out a couple of dead local beasts with my UV lamp. Eastern barred bandicoots glow pink under UV but sugar gliders do not. (My crappy phone camera does not do justice…) pic.twitter.com/49wlwY5DWm

— TMT (@t_mcachan) November 22, 2020

Wombats and the endangered eastern barred bandicoot (Perameles gunnii) are also nocturnal species. Many of the biofluorescent mammals identified so far are either nocturnal or crepuscular (most active at dawn and dusk), but biofluorescence requires a light source for the glow to then re-emit from and there’s less of UV light around at night.

“Perhaps they are able to see much more than we are able to see,” Travouillon hypothesised.

“Predators don’t seem to glow. I think this is because if predators could be seen, they would lose all chance of catching their prey.”

Frankham pointed out however, that many marsupials are nocturnal, so this may not necessarily be a driving factor in evolution of this trait.

While there’s now much speculation about why some mammals glow under UV, we’ve only just realised how wide-spread the phenomenon is. So there’s a lot to do before we can glean any answers.

In response to the fuss over the glowing animals on social media, Lund University evolutionary biologist Michael Bok cautioned:

Be careful about applying ecological or visual relevance to this. Many biological materials fluoresce, but the lighting conditions where it is visible to anything are incredibly unnatural. It is extremely implausible that this is a visual signal. pic.twitter.com/rVeYlVVFqu

— Michael Bok (@mikebok) November 26, 2020

Field studies are required to examine if there even are any advantages or disadvantages of this ability within these animals’ natural environment – but given how vulnerable many of these Australian species are, it’s likely worth checking to see if this trait does impact their ecology or not.

“At this stage, we are all guessing why this is happening, so additional testing will be required to really understand what is going on,” Travouillon said. He’s planning to test more mammals with different lights and see if there really is a pattern with nocturnal mammals.

#Nature

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Eastern Barred Bandicoot (Perameles gunnii)

...a small species of bandicoot that are native to Tasmania and southern Australia. Like other bandicoots the eastern barred bandicoot is nocturnal and will emerge at night to feed on insects on earthworms. During the day it will rest in a self made burrow. It uses its long nose as a probe to locate and consume its prey.

Although it is listed as near threatened the eastern barred bandicoot is still suffering from habit loss and introduced predators. Its range was once distributed across Tasmania but now it is restricted to the eastern side of the island.

Phylogeny

Animalia-Chordata-Mammalia-Marsupialia-Peramelemorphia-Peramelidae-Perameles-P.gunnii

Images: JJ Harrison and australianfauna.com

#Eastern Barred Bandicoot#Perameles gunnii#Bandicoot#Peremelemorphia#Marsupial#Marsupialia#Peramelidae#Perameles#Chordata#Mammalia#Australia#Tasmania

139 notes

·

View notes