#phonotypology

Note

Do you have any literature on sound changes involving ejective consonants? Specifically ejective consonants changing into something else?

I don't know of any general surveys, but several individual cases are of course found in literature in more detail. It would be worthwhile to have some compiled data on this though! For a start I'll collect some examples in this post.

The best-described case might be Semitic, where any handbook (or even just the Wikipedia article) will inform you about *kʼ > q, tsʼ > (t)s etc. being attested in Arabic / Aramaic / Hebrew. Offhand I don't know if there is a particular locus classicus on the issue of reconstructing ejectives for Proto-Semitic, though.

---

Cushitic, which I've been recently talking about, has open questions remaining especially in what exactly to reconstruct for various correspondences involving ejective affricates, but at least the development of the ejective stops seems to be well-established. Going first mainly per Sasse (1979), The Consonant Phonemes of Proto-East Cushitic, Afroasiatic Linguistics 7/1, three developments into something else appear across East Cushitic for *tʼ:

*tʼ > /ɗ/ (alveolar implosive): Oromo, Boni, Arboroid (Arbore, Daasenech, Elmolo), Dullay, Yaaku and, at least word-internally, Highland East Cushitic.

*tʼ >> /ᶑ/ (retroflex implosive): Konsoid (Konso, Dirasha a.k.a. Gidole, Bussa). (As per Tesfaye 2020, The Comparative Phonology of Konsoid, Macrolinguistics 8/2. Some other descriptions give these too as alveolar /ɗ/.)

*tʼ >>> /ɖ/ (retroflex voiced plosive): Saho–Afar, Somali, Rendille.

Presumably these all happen along a common path *tʼ > ⁽*⁾ɗ > ⁽*⁾ᶑ > ɖ. Note though that Sasse reconstructs *ɗ and not *tʼ — but comparison with the case of *kʼ, the cognates elsewhere in Cushitic, and /tʼ/ in Dahalo and word-initially in Highland East Cushitic I think all point to *tʼ in the last common ancestor of East Cushitic. (As per other literature, I don't think East Cushitic is necessarily a valid subgroup and so this last common ancestor may also be ancestral to some of the other branches of Cushitic.)

For *kʼ there is a wide variety of secondary reflexes:

Saho–Afar: *kʼ > /k/ ~ /ʔ/ ~ zero (unclear conditions).

Konso: *kʼ > /ʛ/ (no change in Bussa & Dirasha).

Daasenech: *kʼ > /ɠ/ word-initially, else > /ʔ/.

Elmolo: *kʼ > zero word-initially, else > /ɠ/.

Bayso: *kʼ > zero.

Somali: *kʼ > /q/, which varies as [q], [ɢ] etc.; merges in Southern Somali into /x/). Before front vowels, > /dʒ/.

Rendille: *kʼ > /x/.

Boni: *kʼ > /ʔ/.

though some of them again could be grouped along common pathways like *kʼ > *q > *χ > x, *kʼ > *ʔ > zero.

*čʼ > /ʄ/ happens at minimum in Konso (corresponds to /tʃʼ/ in Bussa & Dirasha). Proposed developments of a type *čʼ >> /ɗ/ in some other languages could go thru a merger with *tʼ first of all.

No East Cushitic *pʼ seems to be reconstructible, but narrower groups show *pʼ > /ɓ/ in Konsoid (corresponds to Oromo /pʼ/) and maybe *pʼ > /ʔ/ in Sidaamo (corresponds to Gedeo /pʼ/; mainly in loans from Oromo).

There is also an unpublished PhD from University of California at LA: Linda Arvanites (1991), The Glottalic Phonemes of Proto-Eastern Cushitic. I would be interested if someone else has access to this (edit: has been procured, thank you!)

Secondary developments of *tʼ and *kʼ in the rest of Cushitic, per Ehret (1987), Proto-Cushitic Reconstruction, Sprache und Geschichte in Afrika 8 (he also reconstructs *pʼ *tsʼ *čʼ *tɬʼ, but I'm less trustful of their validity):

Beja: *tʼ > /s/, *kʼ > /k/.

Agaw: *tʼ > *ts (further > /ʃ/ in Bilin and Kemant), *kʼ > *q (further word-initially > /x/ in Xamtanga and Kemant, /ʁ/ in Awngi)

West Rift: *kʼ > *q (and *tʼ > *tsʼ).

(The tendency for assibilation of *tʼ is interesting; although plenty of Cushitic languages get rid of ejectives entirely, none seems to have a native sound change *tʼ > /t/.)

---

The historical phonology of the largest Afrasian branch, Chadic, is much more of a work in progress, but I would trust at least the following points as noted e.g. by Russell Schuh (2017), A Chadic Cornucopia:

*tʼ > *ɗ perhaps already in Proto-Chadic (supposedly all Chadic languages have /ɗ/);

*kʼ > /ɠ/ in Tera (Central Chadic);

/tsʼ/ in Hausa and some other languages corresponds to /ʄ/ or /ʔʲ/ in some other West Chadic languages, not entirely clear though which side is more original.

Tera /ɠ/ alas does not seem to be discussed in detail in the Leiden University PhD thesis by Richard Gravina (2014), The phonology of Proto-Central Chadic; he e.g. asserts /ɠəɬ/ 'bone' to be an irregular development from *ɗiɬ, while Schuch takes it as a cognate of e.g. Hausa /kʼàʃī/ 'bone'. (Are there two etyma here, or might the other involved Central Chadic languages have *ɠ > /ɗ/?)

If Olga Stolbova (2016), Chadic Etymological Dictionary is to be trusted (I've not done any vetting of its quality) then Hausa /tsʼ/ is indeed already from Proto-Chadic *tsʼ, and elsewhere in Chadic often yields /s/, sometimes /ts/ or /h/. Her Proto-Chadic *kʼ mostly merges with /k/ when not surviving. (She also has an alleged *tʼ with no ejective reflexes anywhere, and alleged *čʼ and *tɬʼ which mostly fall together with *tsʼ, but also show some slightly divergent reflexes like /ʃ/, /ɬ/ respectively.)

---

Moving on, a few other examples I'm aware of OTTOMH include the cases of word-medial voicing in several Koman languages and in some branches of Northeast Caucasian (Chechen and Ingush in Nakh; *pʼ in most Lezgic languages). Also in NEC, the Lezgic group shows complicated decay of geminate ejectives, broadly:

> plain voiceless geminate in Lezgian, Tabassaran & Agul (same also in Tindi within the Andic group);

> voiceless singleton (aspirated) in Kryz & Budux;

Rutul & Tsaxur show some of both of the previous depending on the consonant, as well as word-initially *tsʼː > /d/ and *tɬʼː > /g/ — probably by feeding into the more general shift *voiceless geminate > *unaspirated > voiced (which happens in almost all of Lezgic).

in Udi, both short and geminate ejectives > plain voiceless geminates (plus a few POA quirks like *qʼʷ > /pː/, even though *qʷ > /q/).

Again I don't know if this has been described in better detail anywhere in literature, this is pulled just from the overviews in the North Caucasian Etymological Dictionary plus some review of the etymological data by myself.

Ejectives in Kartvelian are mostly stable in manner of articulation, but there's a minor sound correspondence between Karto-Zan *cʼ₁ (probably = /tʃʼ/) versus Svan /h/ that newer sources like Heinz Fähnrich (2007), Kartwelisches Etymologisches Wörterbuch for some reason reconstruct as *tɬʼ or *tɬ. The Svan development would then probably go as *tɬ⁽ʼ⁾ > *ɬ > /h/, after original PKv *ɬ > /l/.

I do not know very much about the historical phonology of any American languages, including if there's anything interesting happening to ejectives there; if someone else around here does, please do tell!

#phonology#phonotypology#ejectives#historical linguistics#sound change#anonymous#cushitic#chadic#lezgic#kartvelian

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Xun Gong’s identification of the Tangut grade I vs. III/IV contrast with uvularized vs. plain seems convincing, esp. in light of the regional commonness of similar contrasts (and Tangut could have inherited a contrast between plain and velarized/uvularized/pharyngealized vowels from Proto-Horpaic or even, considering Old Chinese, Proto-Sino-Tibetan itself), but what about grade II?

Here’s a wild idea. Epiglottals show up in Tibetic sometimes, and heavily eroded Tibetic varieties are the best typological comparandum for Tangut; furthermore, vowel-accompanying epiglottal trills show up allophonically as part of the register system in Bai, which (as a heavily eroded possibly-Burmo-Qiangic language spoken in the same general region) seems like an acceptable comparandum as well.

Could grade II have been strident vowels?

A three-way contrast between plain, pharyngealized, and strident vowels is apparently attested in Taa... which is the least ideal language to rely on for any phonotypological point at all, but does anyone else have any better ideas?

Unfortunately, this still leaves the ‘tense’, ‘nasal’, and ‘prime’ features, all of which were completely orthogonal to grade, unaccounted for, and Tangut didn’t have contrastive vowel length, did have a known tonal system, probably didn’t have nasal vowels, and seems accepted not to have had diphthongs except in -w. It’s possible that there could’ve been multiple co-occurring phonation features - Takhian Thong Chong (Pearic) has completely orthogonal breathy and creaky features, giving it (for example) /e e̤ ḛ/ and breathy-creaky /e̤̰/, and length is also orthogonal, meaning that short breathy-creaky /e̤̰/ contrasts with long breathy-creaky /e̤̰ː/ - but it doesn’t seem very likely... then again, neither is having 95 vowels in the first place. (Takhian Thong Chong has 84 including diphthongs; Taa has even fewer. If we take Mon-Khmer comparanda, it’s likely that at least one of these ‘features’ was a vowel place distinction, but I’m not convinced that pharyngealization is compatible with a pervasive tense-lax distinction, and I don’t think vowel place is sufficiently orthogonal anyway - in Takhian Thong Chong we see the place contrasts /a ʌ~ɔ e ə o i u/ + /aɪ ao ɛe iə ɤə uə/, which isn’t very Cartesian.)

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

some very nice doubly articulated stops from the Mangbutu-Lese languages: half-implosives [gɓ] and [qɓ], trilled [kpʙ] [source]

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

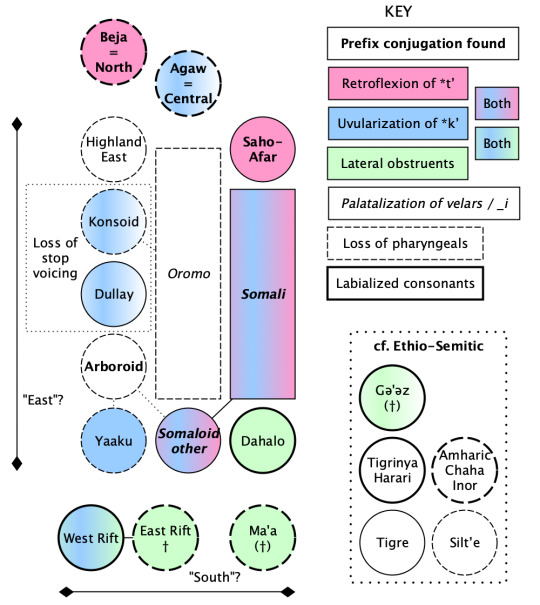

Areal innovations in Cushitic

A small collection of innovations across Cushitic that don't seem to establish any coarser subclassification: broad phonological changes, plus one of the more prominent grammatical divisions — loss vs. preservation of the prefix conjugation, thought to be already old Afrasian inheritance. This already suffices to distinguish every unambiguous group from each other, even though none of the features are unique to some single group! Hopefully this will illustrate the relative heterogeneity of South and especially East Cushitic.

Loss of pharyngeals and ?introduction of labialized consonants indeed continue to Ethio-Semitic, as shown. (Loss of lateral obstruents, again supposedly Afrasian inheritance, however is not quite areally shared between the two: Cushitic has mainly *ɬ > l, Ethio-Semitic *ɬ > s.) To reiterate, it would be also nice to compare further with North Omotic eventually, it already features prominently in any papers on the Ethiopian Sprachbund; but I've not seen thorough enough comparative coverage to assemble anything analogous to this.

The arrangement of the Cushitic subgroups is roughly geographic, in terms of what's adjacent to what. This ends up kind of showing also the large range of Oromo and Somali, not in a way proportional to the real geography though, e.g. HEC + Konsoid + Dullay + Arboroid are actually all cramped in an area smaller than that of just Beja or just Afar, and Agaw is really multiple language islands mainly within the range of Ethio-Semitic, instead of forming a neat cluster between Oromo and Beja. If I had put Ethio-Semitic in here geographically too, all of it would go in the same area where Agaw is now: between Beja, HEC, Oromo and SA.

Crossfading-to-white for Agaw, Konsoid, Dullay indicates that some of these languages, but not all, have *kʼ > qʼ ~ q ~ ʛ. Dashed lines mark the fairly often proposed Arboroid–Somaloid (Omo–Tana) and Konsoid–Oromo groupings and the possible inclusion of Yaaku in Arboroid.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

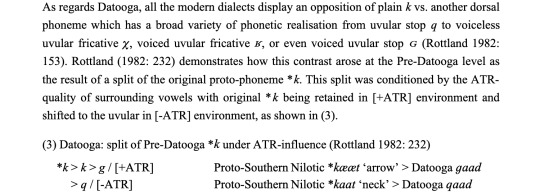

Plosives are devoiced word-finally and when adjacent to another plosive or a fricative. Datooga [dɑtˑɔːkɑ̥] is underlyingly /tattooka/ (or equivalently /daddooɡa/);

looks like Datooga has relatively general initial voicing of all stops, with possible exception for uvular

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Polynesian Atavisms

As per some previous brainstorming on Twitter and initial further reading up: is Polynesian really just one unremarkable subgroup of the Oceanic languages, or should it be maybe considered a distinct entity from the diverse Melanesian / Micronesian groups?

One of the more unusual features in reconstructed Proto-Oceanic as it stands today are the "labialized labial" consonants, *mʷ *mbʷ *pʷ — reflected fairly widely and yielding in daughters variously just that (e.g. Tawala: /mʷ bʷ pʷ/), or velarized labials (e.g. Marshallese: /mˠ pˠ/) or labial-velars (e.g. Lewo: /ŋm kp/), or labialized velars (e.g. Kwaio: /ŋʷ gʷ kʷ xʷ), or also various other less distinct stuff. Where these have common Malayo-Polynesian etymologies (though most don't), they seem to just arise from plain *p/b, *mp/mb, *m without any single conditioning factor. This, among other things, gives many Oceanic languages relatively rich consonant inventories by Austronesian standards.

But in Polynesian there's again no systemic sign of these. Supposedly they just merge back into the labials! (I gather same also in a variety of other Oceanic languages, but the literature I have checked doesn't bother explicitly listing all known cases.) Some cases still also with *m > *mʷ > Proto-Polynesian *ŋ, but my contact linguist senses suggest that this might be loans from some *ŋʷ or *ŋm type language.

So why should we think the labialized labials ever existed in Polynesian at all? It seems to me that the rise of this kind of a highly distinctive new phonological category is unlikely to just immediately disappear again in a single step. The later Polynesian languages do show a trend towards inventory simplification, but very step-by-step. Intermediate stages towards something highly minimal like Hawai'ian can be indeed still attested in the other languages. This is not the case with the loss of the *Pʷ series as far as I can tell. And it's also not the case that Polynesian would be known to group deep into a tree of Oceanic languages, it's usually put as basically direct daughter of a primary branch (Central Pacific) together with Rotuman and Fijian. Neither of which seems to have generally kept the *Pʷ series either. (Fijian has instead unrelated labialized velars, seemingly from POc. plain velars again without much of an explanation. Ross 2011 proposes also a distinct *kʷ already into POc…)

So perhaps there instead existed a "Proto-Near-Oceanic" or the like, which was the real node innovating the *Pʷ series, and which later spread partly further across the original spread of Oceanic — leaving Polynesian now kind of insulated in the east (mostly: there are still the Polynesian outlier languages which have come back west into Micronesia and Melanesia). Maybe there could be even a series of nodes adding the labiolabials in gradually. Some languages like Western Fijian are claimed to not distinguish e.g. *p = *pʷ, but do distinguish e.g. *mʷ | *m (as ŋʷ | m). I don't know the archeology of the original spread of Oceanic in a ton of detail, but it would make sense that skilled seafarers might have formed their first substantial Far Oceanian settlements (i.e. not just trading outposts or the like) on newly found islands entirely like, say, Vanuatu, versus require at least some time to properly claim ground in places like New Britain and Bougainville that already had long-established "Papuan" populations.

(incidentally why do we call these "Papuan", when many of the families have no presence on the island of New Guinea itself? shouldn't something like "Paleo-Oceanic" be more appropriate for this gaggle of non-Austronesian languages?)

Also a second feature that could perhaps be an archaism in Polynesian is the case of the prenasalized consonants, *mb *nd *nr *nj *ŋg (also transcribed *b *d *dr *j *g). They come relatively straightforwardly from the corresponding Proto-Malayo-Polynesian clusters (with some further shuffling: *nt > *nd but *nd > *nr, and *ns > *nc > *nj), but also arise in various cases without a PMP precedent. And then they again merge back with plain stops in Polynesian. The only trace of them having existed is that "lenited *p" > *β turns instead into PP *f, while there's supposedly no "lenited *mb" (currently unsure to me if there is any reason that there should've been one). Sure enough the clusters attested in PMP suggest that Polynesian did go thru at least the usually assumed stage with secondary voiced stops *b *d *g, this is probably more common than direct loss of nasals from clusters like *mp *nt *ŋk. But the "irregular" cases of prenasalized consonants again seem to not be needed for anything in Polynesian, and maybe they could be similarly innovations in Proto-Near-Oceanic.

#historical linguistics#language classification#phonotypology#polynesian#oceanic#austronesian#historical phonology

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

From @yeli-renrong:

Are there examples from outside the Sichuan/Yunnan/Tibet area of the development of postocclusion, as in ɬ ɮ > ɬtʰ ɮd? Is this even diachronically correct, or is postocclusion here a retention after a development of e.g. *l.t- > ɬᵗ?

Examples of "suffricates" as an etymologically single segment aren't exactly common in general of course. At least Bulgarian / Old Church Slavonic *ť *ď > št žd and (some?) Ancient Greek *ď > †zd are diachronically clear cases. If Sino-Caucasianists are on to anything, Burushaski has t- : -lt- from earlier *tɬ. None of these, though, come from a fricative. So yes maybe suggestions of earlier *ɬ *ɮ are indeed simply incorrect and should be rather *lt- *ld- or *tl- *dl- or *tɬ- *dɮ-. The development of Written Tibetan zl- to some varieties' /ld-/ might then be simply routed as fortition to *dl (additionally via *zdl if wanted) plus metathesis. Per Hill (2011: 446) this metathesis has been already proposed long since by Simon in 1929. Or maybe that should be rather Proto-Tibetic *zl-, since this metathesis seems to precede WT!

Tangentially on the topic, Awngi has notably been described as having /s͡t ʃ͡t/, similar to affricates in occurring at syllable boundaries even word-internally. They also fail to be ever broken up by epenthetic [ɨ], but at least this argument is not followed consistently: other homorganic clusters like /mb/ or /rt/ are tolerated within a syllable too; moreover, both the "prestopped fricatives" and certain "tolerated clusters" trigger epenthesis of initial [ɨ]. There does not seem to be evidence for an earlier monophonemic origin. It looks to me that allowing minor complication in syllable structure (existence of some cases of -CC.C- not epenthesized to -CCɨC- or -CɨCC-) would be a better analysis than positing fairly exceptional contour consonants, which brings to my mind the weird Africanist style of analyses that sometimes suggest even clusters like /kɾ/ to be "single consonants".

For that matter, a strictly epenthetic nature of [ɨ] is not tenable for modern-day Awngi anyway: this analysis is originally due to Joswig, who however admits that it is (1) not followed by loanwords from Amharic, (2) not followed by the native noun [sɨsqi] 'sweat' (**[ɨssɨqi]), (3) bled by a proposed degemination of a variety of consonants. All these problems would seem to be solved by treating epenthesis of /ɨ/ as a historical sound change and not a synchronic process.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Some other random interesting tidbits from the Sara language cluster, after half a week of study:

(1) these have vaguely Lithuanian-like "liquid diphthongs", where /CVR/ syllables pattern as akin to /CVV/ in that they can carry two tones; so /ɓaː˩˧/ (ɓàā) 'to find on the ground', /ⁿdeː˩˧/ (ndèē) 'to filter', /ãj˩˧/ (à̰ȳ) 'to flee'; but also: /dʌr˩˧/ (də̀r̄) 'firstborn child', /il˩˧/ (ìl̄) 'to be dark' /nin˧˥/ (nīń) 'corpse' (all these with about the same shape in most Sara varieties). They arise quite straightforwardly by tone cheshirization after loss of final vowels: e.g. in Kaba-Na (a non-Sara language) 'corpse' is /nu˧nu˥/ (nūnú), and e.g. Western Sara /gaŋ˥˧/ (gán̄g) 'a type of drum' corresponds to Central /ga˥ᵑgɨ˧/ (gángɨ̄), Eastern /ga˥ᵑga˥/ (gángá).

(2) consonant systems are fairly tame for the region, there are implosives /ɓ ɗ/ and prenasalized stops + affricate /ᵐb ⁿd ⁿdʒ ᵑg/, but not even labial-velar stops; however, they all have a pretty interesting vowel system /a e i ʌ ɨ ɔ o u/ ±nasalization, with two additional central vowel qualities and an open-mid rounded vowel (more stable than /o/ which varies often with /ʌ/ or /u/; maybe I should call the former of these /ɘ/ instead). Not a lot of evidence of ±ATR pairing amongst these either. Geographically closest relatives have the rather more Sahel-looking /a ɛ e i ɔ o u/. No idea so far how this arises, it kind of seems that most vowels can centralize (*i *u > *ɨ, *a *e *o > *ʌ?), but conditioning seems iffy, and maybe this is backwards and central vowels rather go back to Proto-Sara-Bagirmi or further even. Phoible has an inventory for Bagirmi with two central vowels /ʌ ɘ/ as well; and per Rolle, Faytak & Lionnet (2017) central vowels have indeed been considered an areal feature of central Africa, though they follow instead a hypothesis that this is contact-induced in Sara-Bagirmi.

(3) some more or less clear cases of classic Nilo-Saharan / Macro-Sudanic prefix derivatives (no idea how productive any of this remains):

/a˩ndɨ˧/ (àndɨ̄) 'to bear fruit' : /ka˩ndɨ˧/ (kàndɨ̄) 'fruit'

/il˩˧/ (ìl̄) 'to be dark' : /til˩˧/ (tìl̄) 'darkness, invisibility'

/o˩le˧/ (òlē) 'to boil' : /jo˩le˩/ (yòlè) 'to burn hairs'

/õ˩/ (ò̰) 'to eat from a bowl' : /dõ˩/ (dò̰) 'to bite'

(4) 'friend', /ma˩dɨ˧/ (màdɨ̄) is a tonal minimal pair with 'baboon', /ma˩dɨ˩/ (màdɨ̀), which I'm sure is a great source of puns

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Whither Uvulars

Now that I got to checking up on Oceanic Linguistics, their early release articles seem to have an interesting one by Blevins currently: "Uvular Reflexes of Proto-Austronesian *q: Mysterious Disappearance or Drift Toward Oblivion?" wherein she points out that Proto-Austronesian *q is much more unstable than should be expected.

Differing regular reflexes like *q > k or *q > ʔ establish that this must have remained as its own segment as late as until Proto-Oceanic and various other great-grand-daughter groups. Yet, out of a four-digit number of descendants, there are no more than two languages outside of Taiwan that have a /q/ that seems to come from *q (even one of them, upon reanalysis, apparently instead first merging *k and *q and then backing this *k to /q/ in various environments). Worldwide, uvulars are not all that rare, found in about 20% of languages. So Austronesian is off from the world average here by a factor of 100!

After rejecting a few other hypotheses involving e.g. functional load or language contact effects, Blevins settles on a hypothesis of conditional in/stability of uvulars, which sounds believable to me:

A more relevant structural factor that appears to be strongly correlated with /q/ versus /k/ contrasts is the size and shape of the vowel system. In language families like Semitic, Quechuan, and Eskimo–Aleut (aka Inuit–Yupik- Unangan), where uvular versus velar stop contrasts are reconstructable to the proto-language, and continued robustly, reconstructed vowel systems are small, and are also continued in most daughter languages (…) One possible explanation for the association between small peripheral vowel systems and velar versus uvular stop contrasts relates to perceptual cues of uvulars on adjacent vowels: uvulars are often described with significant “lowering” and “backing” effects on neighboring vowels, so that /i/ might be heard as [e], or /u/ as [o] before a uvular (…) in five vowel systems like /i u e o a/, lowering effects of uvulars would be less salient, or could be mistaken for intrinsic vowel properties.

This checks out also within Austronesian:

The PAN vowel system, as we have seen, was one with three peripheral vowels *i, *u, *a, and one central vowel, *ə. Interestingly, the Formosan languages that show uvular reflexes of *q are precisely those that have either retained the PAN four-vowel system or reduced it further to a three-vowel system with /i u a/.

[B]y PCEMP the vowel system had expanded to *i, *u, *e, *o, *a, *ə (with five peripheral vowels), later reduced to *i, *u, *e, *o, *a in Proto-South Halmahera–West New Guinea and POC (Blust 1993:247). If the *q versus *k contrast was dependent on pho- netic cues that were best realized in a vowel system with /i, u, a, (ə)/, then the expansion of the PCEMP vowel system might be seen as an important structural factor determining a drift away from /q/ in all descendant languages.

I can add that the languages I know with uvulars + large vowel systems (Siberian Uralic and various adjacent Turkic) seem to keep tight reins on the co-occurrence of uvulars and different vowels, often maintaining [q] as a mere "syllable harmonic" allophone of /k/ before back vowels. The case of Northern Khanty and Northern Mansi is also interesting, with a major vowel system collapse leading to a well-loaded /k/ : /χ/ (< *q) contrast. We find generally smallish vowel inventories plus robust uvular inventories also in e.g. NW Caucasian and more northern parts of Na-Dene; also Proto-Indo-European if the "plain velars" were treated as uvulars. Kartvelian might count as an example of sorts of this instability of uvulars, showing vowel systems with 5 or more members + original *q merging with /x/ in 3 languages out of 4. (/qʼ/ remains stable though; and it is also noted by Blevins that languages that have uvulars are also more likely to have ejectives.)

Counterexamples do still exist. NE Caucasian, at least, is a decently large family with sometimes quite large vowel systems and universally maintaining a large stock of uvulars. Cushitic languages also tend to have at least all of basic /a e i o u/ even when having uvulars (be they Awngi or Iraqw or Somali). But then most do not have them, and we could also consider /q/ rather than /kʼ/ being recent rub-off from Arabic in many of them.

---

There is one possible hypothesis that seems to me to have escaped consideration, though: intermediate development? Perhaps, in some major intermediate languages like Proto-Oceanic, *q had changed to a reflex that was no longer a uvular stop but also not yet any of the most common reflexes — for example, an epiglottal stop *ʡ (attested as a reflex of *q in Amis) or a voiceless uvular fricative *χ, that probably should be expected to often decay to various glottal consonants or zero, but maybe could be still also sometimes re-fronted to reflexes like a velar stop /k/ or a velar fricative /ɣ/. Are there any areal tendencies in the frequency of velar (fronted) versus glottal etc. (backed) reflexes of *q across Austronesian? If yes, that might be a point in favor of this explanation.

8 notes

·

View notes

Link

Here it is at last, the kind of a study I’ve been waiting to come along for a while now: a massive statistical bidirectional cluster analysis of the PHOIBLE data (all languages; all segments with > 30 occurences).

Some basic discoveries:

The most basic consonants are /p t k m n l r/. /j w/ as a set can be added as almost as basic, but they correlate more strongly with each other than with the rest of the basic set — i.e. if one is missing, there are decent chances that both are.

The next-most basic consonants are /b d g tʃ dʒ f s ʃ h v z ʒ ɲ ʎ ʔ/. Notably /x ŋ/ do not belong in this cluster; /ŋ/ ends up in the Australian cluster together with retroflexes and alveolo-palatals, /x/ in the gutturals zone.

After these, various MOA or POA extensions tend to form their own clusters or sub-clusters. These do not necessarily exhaust the usage of a particular feature or are not necessarily composed of only one new phonological feature.

Some discoveries that are more curious:

There are two quite well separated clusters of geminate consonants: one for the voiced stops /bː dː gː/, another one for all other common ones.

There are likewise two separate clusters of palatalized consonants: one for coronals, another for peripherals (labials and velars).

/hʲ/ most strongly correlates with /hʷ/ and ends up instead in the general labialized consonants cluster.

Even labialized consonants are split in two: besides the general cluster, there is also a “marked guttural” cluster with /kʷʰ kʷʼ qʷ χʷ/.

There is a somewhat diffuse “spirant cluster” comprising /ɸ β θ ð ɣ/ and, weirdly, the postalveolar nasal /ṉ/. (Checking the data I get the impression these are mostly misentered palatal or palatalized nasals anyway.)

There is a North American cluster with /ɬ ɮ w̰ j̰/; I wonder how strongly just due to Athabaskan.

/tɬʼ/ is more common than plain /tɬ/, which ends up not included in the sample at all.

Not noted in the paper but noticable:

/ɠ/ is too rare to end up included in the implosive cluster, similarly /bv/ too rare to end up included in the affricate cluster (found in 17 and 19 languages respectively).

/ŋː/ does sort into the general geminates cluster; though this could be just because “Australian geminates” are too rare to have been included at all.

Many other “cluster intersection” consonants like /ɓʲ/, /tʲʰ/ or /ⁿdz/ are absent as well, and altogether I predict some of the cluster structure would change if a lower or higher frequency cutoff point had been used.

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

This week I've been looking over the comparative phonology of the Lezgic languages of southern Daghestan and partly northern Azerbaijan, going by the data in the Northeast Caucasian Etymological Dictionary of Nikolayev & Starostin (and whose reconstructions I think could probably use fine-tuning downwards; a look at the actual data is already giving me various ideas on that, but more on it later).

One interesting detail that turns up is seemingly contradictory behavior of the pharyngealized uvular consonants:

in Lezgian proper and a few other varieties these trigger vowel fronting; e.g. *qˤːun > /qːyn/ 'shoulder' (cf. Tabasaran and Rutul /ʁˤun/, Budukh /qˤun/); *oχʷˤɨ- > /χy-/ 'to guard' (cf. Tab. /uχˤ-/, Rut. /uχˤa-/. This would suggest that "pharyngealization" in Lezgic is rather "depharyngealization", that is, [+ATR], not [+RTR].

at the same time, in a few varieties these develop into obstruents articulated even further back; e.g. Agul /ʁˤun ~ ʕun/ 'shoulder'; this would suggest the usual sense of pharyngeal constriction, i.e. indeed [+RTR].

sometimes even both seem to overlap, e.g. Agul /qˤʼuj ~ ʡyj/ 'pitchfork', where the latter dialect variant shows both consonant retraction and vowel fronting.

One way out of this conundrum that I can think of is to consider an additional articulator, i.e. the epiglottis — after all that's the epiglottal stop /ʡ/ in my last Aghul example. N & S's transcription notes also actually describe /ʡ ʕ ħ/ as a group of "emphatic laryngeals", while they reserve the name "pharyngeal" for segments in Agul only that they instead mark "R", "X" (this is a very rare contrast; but corroborated also e.g. by the UCLA Phonetics Lab entry for Agul). Perhaps "pharyngealization" is or has been actually just tongue-root-neutral epiglottalization, and it feeds into two separate processes in the daughter languages: epiglottal > ATR (or even just straight up epiglottal > front) versus epiglottal > RTR ("pharyngealized")?

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Ridiculous Effectiveness of the Comparative Method

A Case from Daatsʼíin

I started poking around with Daatsʼíin upon finding yesterday a 100-word Swadesh list comparing it with two dialects of Gumuz, and wanting to see how much of a Proto-Gumuz could be wrung out of the 89 matches. A decent bit turns out to be indeed doable.

With data running this low though, it will be inevitable that there will be sound correspondences that are plausible but cannot be proven regular. E.g. Daatsʼíin /ɗa-/ ‘to go’ corresponds to Southern Gumuz /ɗá-/, Northern Gumuz /tsá-/; and D /áɗa/ ‘I’ corresponds to SG /ára/, NG /áɗa/. In both cases we have Daatsʼíin /ɗ/ corresponding to a /ɗ/ also somewhere in Gumuz proper, and thus probably these sound correspondences both go back to Proto-Gumuz(ic) *ɗ. But without further data I cannot know if initial fortition to /ts/ or medial lenition to /r/ should be considered regular or irregular. (In fact I don’t even know if limitation to initial / medial position is an actual rule of conditioning, though from general typology of sound change I can assume that *ɗ > r should be more probable medially, *ɗ > ts more probable initially.)

The data still suffices to demonstrate also some non-trivial regular sound correspondences. One clear case is that velar consonant + w + a in Gumuz proper corresponds to plain velar + rounded vowel in Daatsʼíin, with at least five good examples and one more dubious:

D /bekʼo/ ~ G /béékʼwa/ ‘hair’

D /ɗakʼu/ ~ NG /dúkʼwa/ ‘smoke’

D /kʼófakʼu/ ~ SG /kʼófagwa/ ~ NG /kʼwáʃákwa/ ‘navel’

D /kʼókéé/ ~ SG /kʼoca/ ~ NG /kʼwaca/ ‘eye’

D /mágúŋkú/ ~ SG /magókwa/ ~ NG /magáákwa/ ‘night’

? D /voko/ ~ G /ʒákwá/ ‘bone’ (no parallels for /vo/ ~ /ʒa/)

Which side is more original however? No way to tell off the cuff: both Proto-Gumuz *Kwa > Daatsʼíin /Ko ~ Ku/ (seemingly /o/ in 1st syllables, /u/ in 3rd syllables; both options attested in the 2nd syllable) and PG *Ko > Gumuz proper /Kwa/ would be perfectly reasonable sound changes. One option would be to try to dig out data from the more distantly related Koman languages to see what they might point to. Another would be to note that also Southern Gumuz has /kʼo-/ in ‘navel’ and ‘eye’, which could suggest that /Ko/ is an archaism and /Kwa/ is an innovation. However, another argument still points at the opposite: Gumuz proper also allows /Ko/ sequences. Only two of them seem to find Swadesh list cognates in Daatsʼíin, both telling in their own ways however:

D /kʼaw/ ~ G /kʼóá/ ‘dog’

D /kʼôs/ ~ G /kʼósa/ ‘tooth’

In the first we have a word-final labiovelar /w/ in D. If the PG form was something like *kʼawá, the word-medial *w could probably have conditioned preceding *a > o in G, giving some degree of independent confirmation for spreading of rounding from consonants to vowels. The second then should have become G ˣ/kʼwása/ if the /Ko/ ~ /Kwa/ correspondence came from original *Ko. Again, due to lack of data we cannot show either of these correspondences to be regular. But at least they already suffice to show that the hypothesis PG *Kʼwa > D /Ko/ is better than the opposite.

---

Anyway, today I follow up by reading the actual grammar of Daatsʼíin, as linked in my previous post. Guess what jumps at me around noun inflection? Several nouns are pluralized with a prefix of the shape /Cáá-/, with the initial consonant reduplicated from the noun. There are some complications however…

So why is ‘guests’ /kwáákodar/ rather than /káákodar/? Clearly because, at one time, the word-initial consonant to be reduplicated was not /k/ but *kw! That is, /kodar/ : /kwáá-kodar/ comes from earlier *kwadar : *kwáá-kwadar, and *kwa then develops into /ko/, exactly as I have already predicted on the basis of just a handful of Daatsʼíin–Gumuz comparative data.

This is what I would call “ridiculously effective”: any sound law supported by just half a dozen good etymologies and not contradicted by other data is already going have pretty good odds of being correct. Quantity matters some, but in practice, going from 3 examples to 6 examples is already a much bigger improvement than going from 6 to 60 (or 60 to 600).

(As for why the plural prefix remains /kwáá-/ instead of also turning into ˣ/kóó-/ or ˣ/kóá-/ — per Ahland’s closer description in the grammar, what she transcribes as long /aa/ and short /a/ are phonetically realized as [a(ː)] and [ə] respectively. So “*Kwa > *Ko” is phonetically really rather *Kw[ə] > *Ko, and actual open [a] would seem to be not affected.)

#comparative linguistics#comparative method#historical phonology#historical linguistics#phonotypology#gumuz

29 notes

·

View notes

Link

Turns out that Digo (a close relative of Swahili) has a nasalized dental click /ᵑǀ/ that occurs also as a part of just two “non-paralinguistic” (multisegmental) words: /ᵑǀa/ ‘go away!’ and /ᵑǀakule/ ‘miniscule’; perhaps also some other related languages do.

The proposal for a substratal relic nature does not really convince me without any kind of an actual etymological source though (and these are way off from typical substrate vocabulary), I would lean towards the hypothesis of treating this as a rare example of clicks drifting from “paralinguistic” usage also to ideophones.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Place of Articulation Is Structured

from @yeli-renrong:

Isn’t sibilance an entirely phonetic category? (It’s hard for me to pay attention to it because I’ve always assumed it is.) θ vs. s̪ is an exception, but it’s possible to take an America-centric view and say that /θ/ is interdental.

That’s the trick: in featural phonology, sibilance is considered a phonological feature since dental/alveolar is always only a phonetic category. No language contrasts front coronals purely by POA: contrasts of the /t̪ t̳/ type are always accompanied by an apical/laminal distinction.

Actually most models of featural phonology I’ve seen don’t quite operate with "sibilance”, they operate with “stridency”, which extends to include also /f/. (A few I’ve seen to claim that uvular fricatives would also be strident, but this seems mostly unnecessary/unmotivated; they can be pretty much always handled the same as uvular stops.)

The bottom line anyway is that the ±strident and apical/laminal contrasts, which we need anyway to deal with various other cases, can be used to carry quite a bit of other phonological structure too, in particular a large number of differences in place of articulation:

bilabial / labiodental (covered by ±strident)

dental / alveolar (covered by either ±strident or apical/laminal)

retroflex / palatal (covered by apical/laminal)

alveolo-palatal / palatal (covered by ±strident)

in most cases, stop / affricate (covered by ±strident)

Quite often even the stop / fricative contrast could be eliminated in favor of ±strident, which works for plenty of affricate-less and /x/-less languages like French and (standard) Swedish. (And indeed, there is a decently strong worldwide correlation between languages having /k x/ and having affricate/fricative contrasts.)

This doesn’t just allow more neatly describing consonant inventories, it also works as one facet of the explanation for why is it very common for languages to have “skewed” place of articulation setups one way but not the other. /p f/ is very common, and it is also quite common to have /t s/ or /tʲ ʃ/ — but languages that would have instead /p̪ ɸ/, /ts θ/ or /tʃ ç/ are pretty much unattested. (Of course it is also evolutionary, ultimately; fricatives have a tendency to evolve towards stridency.)

Other nice things still follow from this analysis, e.g. the understanding why sibilant affricates are so much more common than plain non-sibilant affricates: phonological affricates are extremely rare, period, and almost all phonetic affricates are phonologically actually “sibilant stops”— i.e. [+strident] [-continuant]. (Some also “lateral stops” or “rhotic stops”.)

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

More Udmurt curiosa: apparently the Ufa dialect contrasts /dʲ/ and /ɟʝ/ word-initially (from earlier *j : *dʑ — and yes, in this order)

/dʲoz/ ‘joint’

/ɟʝoz/ ‘grasshopper’

/dʲʉtɕɨs/ ‘pole for haystack’

/ɟʝʉtɕ/ ‘Russian’

/dʲɨbɨrtɨnɨ/ ‘to bow’

/ɟʝɨgɨrtɨnɨ/ ‘to hug’

There is also /ʑ/, though this only seems to occur word-initially in /ʑeg/ ‘rye’ (contracted from *ɟʝɨʑeg < *dʑɨdʑeg) and a few loanwords from Tatar such as /ʑegɨt/ ‘young’, /ʑin/ ‘tribe, clan’.

20 notes

·

View notes

Photo

This vowel system looks fake but OK

(/ɨ/ also has apparently as its main allophones [ɘ], [ɿ] and [ʅ], “thus keeping it sufficiently distinct in from close-back /ɯ/” — not the main concern I would’ve had about the stability of all this…)

[source]

23 notes

·

View notes