#kartvelian

Text

So

There’s Iberia (above).

And then there’s Iberia.

Do NOT get them mixed up.

#dougie rambles#personal stuff#geography#history#europe#caucasus#iberia#same name#coincidence#probably#my poor attempt at a joke#georgia#sakartvelo#spain#portugal#andorra#gibraltar#basque country#euskal herria#catalonia#Kartvelian#kartli#lazistan

8 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you have any literature on sound changes involving ejective consonants? Specifically ejective consonants changing into something else?

I don't know of any general surveys, but several individual cases are of course found in literature in more detail. It would be worthwhile to have some compiled data on this though! For a start I'll collect some examples in this post.

The best-described case might be Semitic, where any handbook (or even just the Wikipedia article) will inform you about *kʼ > q, tsʼ > (t)s etc. being attested in Arabic / Aramaic / Hebrew. Offhand I don't know if there is a particular locus classicus on the issue of reconstructing ejectives for Proto-Semitic, though.

---

Cushitic, which I've been recently talking about, has open questions remaining especially in what exactly to reconstruct for various correspondences involving ejective affricates, but at least the development of the ejective stops seems to be well-established. Going first mainly per Sasse (1979), The Consonant Phonemes of Proto-East Cushitic, Afroasiatic Linguistics 7/1, three developments into something else appear across East Cushitic for *tʼ:

*tʼ > /ɗ/ (alveolar implosive): Oromo, Boni, Arboroid (Arbore, Daasenech, Elmolo), Dullay, Yaaku and, at least word-internally, Highland East Cushitic.

*tʼ >> /ᶑ/ (retroflex implosive): Konsoid (Konso, Dirasha a.k.a. Gidole, Bussa). (As per Tesfaye 2020, The Comparative Phonology of Konsoid, Macrolinguistics 8/2. Some other descriptions give these too as alveolar /ɗ/.)

*tʼ >>> /ɖ/ (retroflex voiced plosive): Saho–Afar, Somali, Rendille.

Presumably these all happen along a common path *tʼ > ⁽*⁾ɗ > ⁽*⁾ᶑ > ɖ. Note though that Sasse reconstructs *ɗ and not *tʼ — but comparison with the case of *kʼ, the cognates elsewhere in Cushitic, and /tʼ/ in Dahalo and word-initially in Highland East Cushitic I think all point to *tʼ in the last common ancestor of East Cushitic. (As per other literature, I don't think East Cushitic is necessarily a valid subgroup and so this last common ancestor may also be ancestral to some of the other branches of Cushitic.)

For *kʼ there is a wide variety of secondary reflexes:

Saho–Afar: *kʼ > /k/ ~ /ʔ/ ~ zero (unclear conditions).

Konso: *kʼ > /ʛ/ (no change in Bussa & Dirasha).

Daasenech: *kʼ > /ɠ/ word-initially, else > /ʔ/.

Elmolo: *kʼ > zero word-initially, else > /ɠ/.

Bayso: *kʼ > zero.

Somali: *kʼ > /q/, which varies as [q], [ɢ] etc.; merges in Southern Somali into /x/). Before front vowels, > /dʒ/.

Rendille: *kʼ > /x/.

Boni: *kʼ > /ʔ/.

though some of them again could be grouped along common pathways like *kʼ > *q > *χ > x, *kʼ > *ʔ > zero.

*čʼ > /ʄ/ happens at minimum in Konso (corresponds to /tʃʼ/ in Bussa & Dirasha). Proposed developments of a type *čʼ >> /ɗ/ in some other languages could go thru a merger with *tʼ first of all.

No East Cushitic *pʼ seems to be reconstructible, but narrower groups show *pʼ > /ɓ/ in Konsoid (corresponds to Oromo /pʼ/) and maybe *pʼ > /ʔ/ in Sidaamo (corresponds to Gedeo /pʼ/; mainly in loans from Oromo).

There is also an unpublished PhD from University of California at LA: Linda Arvanites (1991), The Glottalic Phonemes of Proto-Eastern Cushitic. I would be interested if someone else has access to this (edit: has been procured, thank you!)

Secondary developments of *tʼ and *kʼ in the rest of Cushitic, per Ehret (1987), Proto-Cushitic Reconstruction, Sprache und Geschichte in Afrika 8 (he also reconstructs *pʼ *tsʼ *čʼ *tɬʼ, but I'm less trustful of their validity):

Beja: *tʼ > /s/, *kʼ > /k/.

Agaw: *tʼ > *ts (further > /ʃ/ in Bilin and Kemant), *kʼ > *q (further word-initially > /x/ in Xamtanga and Kemant, /ʁ/ in Awngi)

West Rift: *kʼ > *q (and *tʼ > *tsʼ).

(The tendency for assibilation of *tʼ is interesting; although plenty of Cushitic languages get rid of ejectives entirely, none seems to have a native sound change *tʼ > /t/.)

---

The historical phonology of the largest Afrasian branch, Chadic, is much more of a work in progress, but I would trust at least the following points as noted e.g. by Russell Schuh (2017), A Chadic Cornucopia:

*tʼ > *ɗ perhaps already in Proto-Chadic (supposedly all Chadic languages have /ɗ/);

*kʼ > /ɠ/ in Tera (Central Chadic);

/tsʼ/ in Hausa and some other languages corresponds to /ʄ/ or /ʔʲ/ in some other West Chadic languages, not entirely clear though which side is more original.

Tera /ɠ/ alas does not seem to be discussed in detail in the Leiden University PhD thesis by Richard Gravina (2014), The phonology of Proto-Central Chadic; he e.g. asserts /ɠəɬ/ 'bone' to be an irregular development from *ɗiɬ, while Schuch takes it as a cognate of e.g. Hausa /kʼàʃī/ 'bone'. (Are there two etyma here, or might the other involved Central Chadic languages have *ɠ > /ɗ/?)

If Olga Stolbova (2016), Chadic Etymological Dictionary is to be trusted (I've not done any vetting of its quality) then Hausa /tsʼ/ is indeed already from Proto-Chadic *tsʼ, and elsewhere in Chadic often yields /s/, sometimes /ts/ or /h/. Her Proto-Chadic *kʼ mostly merges with /k/ when not surviving. (She also has an alleged *tʼ with no ejective reflexes anywhere, and alleged *čʼ and *tɬʼ which mostly fall together with *tsʼ, but also show some slightly divergent reflexes like /ʃ/, /ɬ/ respectively.)

---

Moving on, a few other examples I'm aware of OTTOMH include the cases of word-medial voicing in several Koman languages and in some branches of Northeast Caucasian (Chechen and Ingush in Nakh; *pʼ in most Lezgic languages). Also in NEC, the Lezgic group shows complicated decay of geminate ejectives, broadly:

> plain voiceless geminate in Lezgian, Tabassaran & Agul (same also in Tindi within the Andic group);

> voiceless singleton (aspirated) in Kryz & Budux;

Rutul & Tsaxur show some of both of the previous depending on the consonant, as well as word-initially *tsʼː > /d/ and *tɬʼː > /g/ — probably by feeding into the more general shift *voiceless geminate > *unaspirated > voiced (which happens in almost all of Lezgic).

in Udi, both short and geminate ejectives > plain voiceless geminates (plus a few POA quirks like *qʼʷ > /pː/, even though *qʷ > /q/).

Again I don't know if this has been described in better detail anywhere in literature, this is pulled just from the overviews in the North Caucasian Etymological Dictionary plus some review of the etymological data by myself.

Ejectives in Kartvelian are mostly stable in manner of articulation, but there's a minor sound correspondence between Karto-Zan *cʼ₁ (probably = /tʃʼ/) versus Svan /h/ that newer sources like Heinz Fähnrich (2007), Kartwelisches Etymologisches Wörterbuch for some reason reconstruct as *tɬʼ or *tɬ. The Svan development would then probably go as *tɬ⁽ʼ⁾ > *ɬ > /h/, after original PKv *ɬ > /l/.

I do not know very much about the historical phonology of any American languages, including if there's anything interesting happening to ejectives there; if someone else around here does, please do tell!

#phonology#phonotypology#ejectives#historical linguistics#sound change#anonymous#cushitic#chadic#lezgic#kartvelian

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

🐸✏️🇬🇪 "ბაყაყი" [baq̇aq̇i]

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

#russia#georgia#sakartvelo#not all russians#russophobia#xenophobia#racism#kartvelians my beloved I am so sorry you had to see this.#cannot believe this bitch treated living in a country so beautiful and welcoming as some kind of tempering#they were welcomed as ''''refugees of putin regime''' and they dare to act like that

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

I think it would be funny, if from Baumeister siblings only Tita would be able to wield equivalent of Mingrelian and she would wield it well enough to argue with her mother in Mingrelian.

#Mingrelians really do deserve my respect. They have to learn how to speak Georgian and then some foreign language.#The same goes to Svans and Lazs#On my course in university there are a lot of Mingrelians. When they start to speak Mingrelian I am confused (not in a bad way)#and fascinated. Because I barely understood anything. But Mingrelian#Svan and Laz languages are endangered treasures.#I didn't expect that I would start a full blown rant about Kartvelian languages in my silly post about my OC#Mokem Series#oc#ocs#Tita Baumeister may be a minor. somewhat spoiled and pity character. But oh boy. She roasts people in Mingrelian.#The problem is I won't be able to show how she roasts people in this beautiful language 'cause I don't know this language.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Someone needs to draw Jason of Iolkos wearing this

#for those not in the know jason married#medea#princess of kolkhis in what is now georgia#and the native name for georgia is sakartvelo hence kartvelian#mythology#greek mythology#argonautica#argonauts#jason and the argonauts

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mkhedruli is surprisingly easy to learn

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

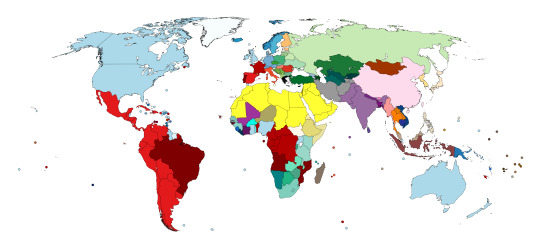

Most commonly spoken language in each country

I had to separate the legend from the map because it would not have been legible otherwise. I am aware that the color distinctions are not always very clear, but there are only so many colors in the palette.

The legend is arranged in alphabetical order and languages are grouped by family (bullet points), with branches represented by numbers and followed by the color palette languages within them are colored in, as follows:

Afroasiatic

Chadic (Hausa) — ocher

Cushitic (Oromo and Somali) — light yellow-green

Semitic (from Arabic to Tigrinya) — yellow

Albanian — olive green

Armenian — mauve

Atlantic-Congo

Benue-Congo (from Chewa to Zulu) — blue-green

Senegambian (Fula and Wolof) — faded blue-green

Volta-Congo (Ewe and Mooré) — bright blue-green

Austroasiatic (Khmer and Vietnamese) — dark blue-purple

Austronesian

Eastern Malayo-Polynesian (from Fijian to Wallisian) — dark brown

Malayo-Polynesian (Palauan) — bright brown

Western Malayo-Polynesian (from Malagasy to Tagalog) — light brown

Eastern Sudanic (Dinka) — foral white

Hellenic (Greek) — black

Indo-European

Germanic (from Danish to Swedish) — light blue (creoles in medium/dark blue)

English-based creoles (from Antiguan and Barbudan to Vincentian Creole)

Indo-Aryan (from Bengali to Sinhala) — purple

Iranian (Persian) — gray

Romance (from Catalan to Spanish) — red (creoles in dark red)

French-based creoles (from Haitian Creole to Seychellois Creole)

Portuguese-based creoles (from Cape Verdean Creole to Papiamento)

Slavic — light green (from Bulgarian to Ukrainian)

Inuit (Greenlandic) — white

Japonic (Japanese) — blanched almond

Kartvelian (Georgian) — faded blue

Koreanic (Korean) — yellow-orange

Kra-Dai (Lao and Thai) — dark orange

Mande (from Bambara to Mandinka) — magenta/violet

Mongolic (Mongolian) — red-brown

Sino-Tibetan (Burmese, Chinese*, and Dzongkha) — pink

Turkic (from Azerbaijani to Uzbek) — dark green

Uralic

Balto-Finnic (Estonian and Finnish) — light orange

Ugric (Hungarian) — salmon

* Chinese refers to Cantonese and Mandarin. Hindi and Urdu are grouped under Hindustani, and Bosnian, Croatian, Montenegrin, and Serbian are grouped under Serbo-Croatian.

#langblr#lingblr#spanish#english#french#german#catalan#russian#mandarin#hausa#somali#arabic#albanian#armenian#swahili#ewe#moore#wolof#vietnamese#samoan#palauan#malay#dinka#greek#tok pisin#hindustani#persian#haitian creole#papiamento#greenlandic

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

Controversial origin of Halime Sultan

For many years the life of Halime Sultan had been a mystery. Not only her place of birth,but even her period in harem and tenure as Valide was unknown. Many thought the mother of Mahmud was killed along with him, some said she survived, but was banished. Even her Muslim name was unknown and was mentioned as fulane sultan for quite a long time, until it was found that she was called Halime sultan.

Like almost everything about her life her origin was mostly a mystery, However today it is accepted that she was from Caucasia, particularly from Abkhazia. However, that doesn't make everyone clear about her ethnicity. Confusion mainly comes because the term "Abkhazian" might include several people: Native Abkhazians, who settled here in ancient times, there were two major tribes in Abkhazia ubykh-abkhazs(genetically closer to Circassians) and Georgian-abkhazs(almost genetically identical to western Georgians). However, the number of people in each tribe varied from time to time, however generally Georgian-abkhazians were more loosely-settled, mainly because during the rise of civilization during iron age,pre-classical and classical antiquity, when Abkhazia was part of first Kingdom of Colchis and then kingdom of Egrisi(lazica), both were kartvelian kingdoms, created after unification of native Kartvelian tribes that lived there, two kingdom covered teritories from todays Abkhazia to some parts of eastern Anatolia. Therefore, Georgian-abkhazs promoted that time. In 697, the kingdom of Egrisi devided, into the de-facto kingdom of Abkhazia from 697-780's and the official kingdom of Abkhazia from early 780's to 1008 that included not only modern Abkhazia,but whole teritories of modern eastern Georgia and parts of Turkey and Russia . The official language of the pre 780's kingdom was Georgian, was ruled by Georgian-abkhaz Nobel families and was almost entirely settled by Georgians. After the 780s it was even more dominated by Georgians and that was time, when on the territories of the modern days republic of Abkhazia along with Georgian-abkhazs and ubykh-abkhazs western Georgians actively started to settle. From 1008 to 1490's it became part of the united kingdom of Georgia. After the 1490s it was invaded by Mongolians and divided into western and eastern parts. That is a period when Circassians slowly started to enter Abkhazian territories. Now back to the topic, up until late sixteenth century Abkhazia was Georgian dominated land, in 1570's same time as ottomans, many Circassian tribes started infiltrating Abkhazia and unlike peaceful natives, started to invade homes of weakened Georgians and as a result during the climax of invasion in 1580-90's mass slave trade burst out and thousands of Georgian-abkhaz and mingrelian girls found themselves in ottoman slave market.

Halime sultan was born around 1568-70, therefore in 1580-90's she could have been anywhere from 10-12 to 20-22 years old, considering Mehmed III received his sanjak in 1583, Halime was likely gifted to him that or next year, at very least she was already favourite in 1586, so she was bought quite before that time. So perhaps she was freshly brought little Georgian in the Ottoman slave market? Everything in this theory fits, her age, statistics, fact that slave markets were flooded by Georgians suggest that when we say that Halime was Abkhaz, it means Georgian-abkhaz, not Ubykh-abkhaz and definitely not non-native Circassians.

#history#historical drama#16th century#magnificent century#magnificent century kosem#mc: kosem#ottoman empire#ottomanladies#historical events#georgia#abkhazia#Georgian history#history of Georgia#halime sultan#ottoman sultanas#sultanate of women#sultanas#circassian#women in politics#historical figures#historyedit

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

In Anthropology, there are three main distinctions of what it means to be “from” somewhere

It could mean your ethnicity — eg, where are your parents from or your ancestors. What tribe of people did does your genotype come from, specifically pre-1492

It could mean your nationality — eg, where are you legally from, where is your passport country, where do you pay taxes

Or it could mean where you were enculturated — eg, where did you grow up, where is your accent from, where did you go to school, where were you born

(Depending on the context it may also be where were you a few minutes ago, but usually we use a different tense like “where did you come from”)

I think U.S. Americans of non-WASP or WASP-passing origin often get confused by how WASP Americans condescendingly ask the question “where are you really from”

For many people, nationality is the most important factor in determining where they are from, and this question implies that their national identity is less valid than a WASP’s, hence the animosity towards this micro aggression

This really only is a problem in the United States

I’ve heard it happening in Canada, Australia, and New Zealand, but because ethnic hegemony is much higher their, it’s more rare

And in pretty much every other country, the answer to the three is all the same.

Most people in Lithuania are Lithuanian and have a Lithuanian passport and grew up in Lithuania

There are thousands of, say, Americans who are Chinese American and have USA passport but have lived in Hawaii, Vermont, Michigan, and France over their lives

But all of these factors are what makes humans so complex, and I think it is personally a fault of the English language that there is little nuance and a lot of vagueness in our terminology

Asking “where are you from ethnically”, “what passport do you hold”, “what locations did you experience your life in prior to here” all feel intrusive and robotic

We need better alternatives!!!

Sincerely,

A person who is Texian, Mexican, Irish, and Polish by ethnicity, U.S. American by Nationality, and South Carolinian, Douglassian (Washington DC), Kartvelian, Fijian, Qatari, German, South Floridian by enculturation

#humans are so cool and it’s failure of our language to not represent our coolness#anthropology#linguistics#human#culture#ethnicity#nationality#enculturation#latina#latino#asian american#microaggressions#miami

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

“It’s nonsense that all the elves or dwarves or whatever all speak the same language!”

My elves live 24 times as long as humans. Given the obvious most significant factor in linguistic change is “individual speakers only live so long”, that puts Modern English, roughly 550 years old, at 13,200 years, and Middle English, the common ancestor of Scottish and English (which are largely mutually intelligible), roughly 925 years old, at 22,200. Modern Greek, which begins roughly 1675 years ago (early Byzantine works are roughly as comprehensible to educated living Greeks as Nathaniel Hawthorne is to living Americans) would be 40,200 years old. Dwarves live 20 times as long as humans, which puts Modern English at 11,000, Middle English at 18,500, and Modern Greek at 33,500.

The furthest back we can trace any entire human language group is I think about 9,000 years. (Maybe 11,000? I think 9,000 is Semitic and 11,000 is Afro-Asiatic.) Even fucking Proto-Nostratic, the hypothetical and highly doubtful ancestor of Indo-European, Afro-Asiatic, Kartvelian, Dravidian, Uralic, Mongolic, Turkic, Tungusic, and probably Koreanic and Japonic, is only at most 15,000.

So…no I don’t think it’s remotely implausible that people who spread around at the same speeds as humans, but live onescore or twodozen times as long, would have anything remotely comparable to the linguistic diversity humans exhibit. Especially since they also always had at least some access to magic for transport and communication.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Georgia is home to 11 endangered languages, according to UNESCO. Like standard Georgian, three of these belong to the Kartvelian language family. But unlike the country’s primary language, Megrelian (or Mingrelian), Svan, and Laz do not enjoy official status or protection. Nor are there official figures on the exact number of speakers, due in part to persistent fears that promoting smaller Kartvelian languages could fuel linguistic nationalism or, worse, separatism. For Georgians, separatism is not an abstract concept: the country fought bitter wars in the early 1990s in Abkhazia and South Ossetia, two breakaway regions that Russia occupied as the result of another war in 2008. Moscow’s habit of instigating and exploiting separatist sentiment in neighboring countries only causes more concern. That said, language advocates maintain that their cause has nothing to do with secession and everything to do with preserving Georgia’s cultural heritage.

This story first appeared in The Beet, a weekly email dispatch from Meduza covering Central and Eastern Europe, the Caucasus, and Central Asia. Sign up here to get the next issue delivered directly to your inbox.

In July 2023, a new translation of the Bible was released in Georgia — the first edition ever published in the Megrelian language. Completed at the independent initiative of Giorgi Sakhokia, a 75-year-old Megrelian speaker, the translation sparked debate on social media. Since the Bible is already available in the Georgian language, critics wondered, why is this translation necessary at all?

Like Georgian, Megrelian is part of the Kartvelian language family, along with Svan and Laz. While many linguists consider these separate languages, Georgians often refer to the latter three as dialects. But the mutual intelligibility between Megrelian and Georgian is very low, Thomas Wier, an assistant professor of linguistics at Free University of Tbilisi, told The Beet.

According to the 2021 Caucasus Barometer survey, seven percent of Georgians speak Megrelian in daily life. The number of Megrelian speakers in Georgia is estimated at around 300,000 people, most of whom reside in the western Samegrelo region on the Black Sea coast. Yet, the language has no official status and, as a result, remains primarily a spoken language, seldom used in writing.

Melor Shengelia was born in Samegrelo’s regional capital, Zugdidi, and has spoken Megrelian with his family since childhood. But his younger relatives are no longer learning the language, he says. The generation of children growing up in the region today are becoming what’s known as “passive speakers,” meaning their parents speak to them in Megrelian, but they respond in Georgian — the language they see in the media, speak with friends, and study in school.

“[Parents] prefer that their kids know Georgian, and kids prefer to know English to use TikTok. [...] Everything is in English or in Georgian,” said Maka Chitanava, who’s also from Zugdidi and speaks Megrelian with her close family members.

The declining use of Megrelian has led UNESCO to designate the language as “definitely endangered.” This classification signifies that children “no longer learn the language as a mother tongue at home,” raising fears that it may eventually disappear.

“My nephews are seven or eight years younger than me and when they start speaking Megrelian, it’s so broken, they make so many mistakes,” said Shengelia, who’s 25 years old. “Even though they can understand, they can't speak properly. That means that their children won't be able to speak Megrelian.”

‘Languages die out, domain by domain’

Most Georgians rarely encounter smaller Kartvelian languages in their daily lives. Natia Liluashvili, who grew up in Georgia’s Imereti region, heard Megrelian for the first time while on a school trip to Samegrelo when she was about 14 years old. The fact that she couldn’t understand the language people were speaking around her was a shock.

“When I came [to Zugdidi] and was walking down the street, I knew I was still in Georgia — but people were speaking a different language,” Liluashvili recalled. “I couldn't understand anything.”

She also remembers singing songs in Megrelian at school, although she didn’t understand the words.

Shengelia says he often encounters people in Tbilisi, Georgia’s capital, who are surprised to learn that his family speaks Megrelian at home. “Even though everyone knows that Megrelian people speak Megrelian, it’s still kind of surprising for them,” he told The Beet. “They just don't have that much information about [it].”

Then there’s the fact that the vast majority of Megrelian speakers are bilingual. As a result, they tend to code switch, alternating languages based on the circumstances or listener at hand. Shengelia, who has lived in Tbilisi for six years, typically speaks Georgian unless he meets another Megrelian speaker. In Samegrelo, he uses Megrelian with his family and friends, and in places like the grocery store, but he opts for Georgian when he’s in what he deems more “formal” spaces such as a bank, a government institution, or a hospital.

“Languages typically don't die out all at once. They die out, domain by domain, whether you use it in public, school, or at the doctor’s office,” Wier explained.

Over time, Georgian loan words have also made their way into the Megrelian language. According to Timothy Blauvelt, a professor of Soviet and Post-Soviet Studies at Ilia State University in Tbilisi, this is due to the limited written documentation of the language, which leads Megrelian speakers to fill in their vocabulary gaps with borrowed words.

“This is one of the biggest problems for the Megrelian language. It has so many Georgian and Russian words, even though there are actual words in Megrelian [with] the same meaning,” Shengelia said. “Sometimes when my grandmother and grandfather say [certain] words, I’m surprised; I didn’t think we had a word for that.”

Svan song

Unexpected events can suddenly and drastically alter linguistic communities. The steep decline of the Svan language is a prime example, Wier told The Beet.

In 1987, a series of avalanches devastated Georgia’s mountainous Svaneti region, damaging Svan villages and killing 85 people. The Soviet authorities decided to evacuate 16,000 residents, most of whom were Svan speakers. Around 2,500 families were resettled elsewhere in Georgia, and the Svan language became endangered in a matter of years. The migration of Georgian and Megrelian speakers into Svaneti, who communicate with Svan speakers in Georgian, further exacerbated language loss in the region.

UNESCO classified Svan as “definitely endangered” in 2011. But Wier fears the language is now at risk of going extinct. “If there’s not a systematic sea change for the Svan language in terms of people’s attitudes and in terms of government funding and aid to communities, I think this one will die out, because its current status has just so drastically declined in just the last 30 years,” he said.

Teaching Georgia’s endangered languages in schools is one possible remedy: Chitanava believes that Megrelian should be taught in the Samegrelo region at least. “In Georgian language classes, we could have a few topics devoted to the Megrelian and Svan languages and maybe also Laz,” she suggested. “So kids can understand how these languages are related, what is interesting about these languages, and that it’s [part of] their cultural heritage.”

Georgian President Salome Zourabichvili has expressed support for teaching Megrelian and Svan in schools. But overall, there’s little political will to provide any government assistance for these endangered languages, primarily due to the association of linguistic identity with ethnicity and, by extension, the belief that granting language rights could spark separatist sentiment.

According to Givi Karchava, the co-founder of the Megrelian Language Association, this attitude is one of the biggest challenges his organization faces — besides a lack of funding. “Any type of activity which shows Megrelian as equal to the Georgian language [...] is understood as separatism,” he said.

The prospect of Georgia signing the European Language Charter, which would mandate the necessary steps to protect and promote minority languages, provokes similar concerns, experts told The Beet.

“There’s basically all these fears about the territorial disintegration of Georgia that some people have,” said David Sichinava, an adjunct research professor at Carleton University. The debate around language rights, he explained, triggers anxieties about a possible domino effect wherein minority populations demand greater autonomy. “That’s a challenge that perhaps is causing these languages [to be neglected],” Sichinava surmised.

“My personal opinion is that signing the document [the European Language Charter] or ratifying it is too politically charged and probably will be for a long time,” Blauvelt said.

A historical legacy

The widespread fear of separatism in Georgia stems from recent history, namely, the 1991–1993 Georgian Civil War, which saw intense fighting between Tbilisi and the separatist regions of Abkhazia and South Ossetia, and the 2008 war with Russia, when Moscow occupied the breakaway territories.

These wars significantly impacted the distribution of Megrelian speakers. The hostilities in Abkhazia in the 1990s displaced more than 200,000 people, including tens of thousands of Megrelian-speaking Georgians who fled to neighboring Samegrelo and other regions. The 2008 war also caused large-scale displacement.

Melor Shengelia’s mother fled Abkhazia’s capital, Sokhumi, during the war in the 1990s and then moved to Samegrelo. Shengelia’s grandfather stayed behind to defend the family home. “People have this fear of separatism, [but] they have to remember that Megrelians were the people who were fighting for Abkhazia [to remain part of Georgia],” Shengelia recalled. “They don’t have any intention to separate from the rest of the Georgians.”

That said, the understanding of language as intrinsically linked to ethnicity has deep roots in Georgia, going back to the Soviet Union’s nationality policy, Blauvelt told The Beet. First introduced in the 1920s, this “nation-building” program assigned officially recognized ethnic groups — referred to as “nationalities” — their own territories within the USSR and promoted national languages through culture and education. (This policy was rolled back in the 1930s, giving way to political purges, deportations of groups deemed “enemy nations,” and Russification).

“The Soviet understanding is really still fundamental in shaping the way people view their own identity [and] why they view national identity as something primordial, something unchanging,” Blauvelt explained. “This question of dialect and language, and where these minority languages fit, is so politically charged, because it’s ultimately part of those discourses of ’national greatness’ and national identity.”

The authorities in Georgia haven’t recorded Megrelian speakers as a distinct group since the 1926 Soviet census. And when Russia added this category to its own census in 2010, only 600 respondents identified as Megrelians.

‘We shouldn’t sacrifice our cultural heritage’

Shengelia says it’s fundamentally misguided to fear that promoting Megrelian could lead to separatism. “The Megrelian language belongs to Georgia and all Georgian people. By underlining that it’s only the language of Megrelian speakers, you are promoting this kind of separation,” he argued. “Megrelian speakers don't think that it’s only their language.”

According to Sichinava, activists working to preserve Megrelian and Svan also share this view. “What’s important and what’s so interesting is that none of those activists say that we are different peoples. They say, ‘We want to preserve the language, but we are Georgian,’” he noted.

The Beet’s other sources also felt that identity politics shouldn’t impede efforts to keep Georgia’s endangered languages alive.

Despite the challenges, Chitanava believes that shifting attitudes in recent years may increase the odds of maintaining Georgia’s language diversity. “Thirty years have already passed since our independence and our war in Abkhazia. I think this pain and fear of the country’s disintegration is less [prevalent],” she told The Beet. “We shouldn’t sacrifice our cultural heritage to these fears and phobias.”

Although not a Megrelian speaker, Liluashvili said that she supports initiatives to preserve the language — including the possibility of teaching it in schools — because it’s part of Georgia’s heritage. “It's our culture. Especially when we are such a small country, we should protect and save our diversity,” she said. “Language is one of the most important parts of diversity.”

For now, however, efforts to preserve Georgia’s smaller Kartvelian languages are concentrated at the grassroots level. In 2018, software developer Hary Kodua created an online Megrelian-Georgian dictionary to make the language more accessible to young people. At this writing, the dictionary contains 120,000 words.

In 2020, Givi Karchava and Giga Kavtaradze founded the Megrelian Language Association with the goal of “saving the Megrelian language from disappearing.” Today, the group publishes Megrelian-language books, runs a magazine, and coordinates seminars.

Megrelian and Svan self-study books are also available, as is a Megrelian version of Wikipedia and translations of well-known fiction, such as the Georgian epic The Knight in the Panther’s Skin.

Karchava himself translated George Orwell’s Animal Farm and Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s The Little Prince into Megrelian. “Georgian society and the state are more tolerant toward the Megrelian language now,” he told The Beet. “Let’s see what happens next. We are full of hope.”

8 notes

·

View notes

Note

Linguistically, Azerbaijani, Armenian, Kartvelian (Georgian), and Abkhaz aren't even in the same language families! Like the highest level groupings - obviously culture is more than just language but that's a big difference

I was thinking that, which is why I wasn't confident enough to say it in the post--I know Azerbaijan speaks a Turkic language, but I wasn't sure whether that was a product of invasion without actual replacement, which might not change the local culture that much, or migration, which might bring some very different customs. then again, similar environments might reinforce similar cultures no matter what the origin.

I'm curious how four extremely different languages wound up in such close proximity, but every time I encounter that region in history books, it's because it was too mountainous to invade--so maybe that geography is also a barrier to cultural blending.

I should just read up on this, it's long past time.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

In this chapter, Cambell & Poser are discussing specific proposed macrofamilies, which is very interesting--the Nostraticists in particular have actually put a ton of time and effort into trying to prove their theory, although in C&P’s opinion they don’t succeed.

It’s interesting also just how ambitious most of these proposals are; it’s rarely, “OK, I’m going to focus on the putative PIE-Finno-Ugric connection, and really prove that,” it’s more like “What if we took PIE and Finno-Ugric and Dravidian and Afroasiatic and Sumerian and Karvelian, and a whole bunch of other languages, and tried to prove a relationship between them all at once.” That is a bigger task, and a much riskier one. You don’t need (for example) Sanskrit to show Gothic and Latin are related; obviously it helps complete the picture, but Grimm’s Law and Verner’s Law are still perfectly discoverable just with those two, as well as lots of other connections. It seems to me that even if Nostratic were a valid grouping, you should focus on proving the relatedness of one family at a time!

But then of course you’d have fewer suggested correspondence sets to work with--part of the reason Nostratic feels plausible as a hypothesis to its proponents is that if you can’t find an etymon in Finno-Ugric, you can search Kartvelian; and if you can’t find one there, you can search Dravidian, and so forth. In the end, there seem to be not that many etymons that are common across all branches, which is kind of a problem IMO! And the ones that are don’t exhibit regular sound correspondences, which is a pretty strong signal this is not a useful grouping.

(Of course, compared to Greenberg’s Eurasiatic, this still looks like scholarship of the first order; Illich-Svitych and Starostin at least trying to find sound laws. Greenberg doesn’t even bother.)

#afaict greenberg apparently did lots of great work early in his career#it's only later that he kind of went off the rails with his lexical mass comparison#but c&p talk pretty favorably about a lot of his earlier work#i wonder what happened there

12 notes

·

View notes