#picuris pueblo

Text

In Memory of Richard Mermejo

In Memory of Richard Mermejo

September 20, 1945 – January 27, 2024

By Severin Fowles, Michael Adler, and Lindsay Montgomery

Richard Mermejo, former Governor of Picuris Pueblo, passed away on Saturday, January 27, 2024. During his 78 years with us on Mother Earth, Richard touched countless communities through his friendship, mentorship, and activism. He was, firstly, a cultural leader at Picuris…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Preliminaries: War of the Utility Wares!

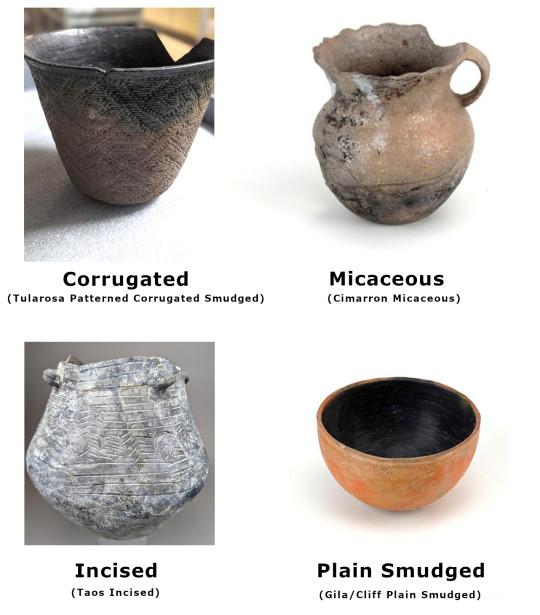

Most pottery you find in archaeological sites isn't painted. Most pottery is unslipped, undecorated utility ware - with the assumption that "utility" typically here means "cooking over a fire." Sometimes grain storage. Usually cooking, though.

It doesn't mean they can't be beautiful in their own right. And one of my friends is working on a dissertation which among other things argues that "surface treatments" like incising and corrugation should be considered "decoration" too, when usually in archaeology "decorated" means "painted." There were lots and lots and lots of types of utility wares. Some were plain. Some were gorgeous.

So this is a Preliminary Round - four different styles traditionally called utility ware will go up against each other... only two will move on to represent utility wares in the final bracket.

Vote for your favorite: More information about each is under the cut:

Corrugated

Mesa Verde Corrugated jars. Southern Colorado, AD 1100-1300.

There are SO many different types of corrugated pottery; if I listed them all we'd be here all day. However, they all have commonalities: They were primarily (though not exclusively) made in the Mogollon cultural region, primarily (though not exclusively) plain and unpainted, and primarily (though not exclusively) used for cooking.

In this region, potters don't use pottery wheels. Pots are hand-built, typically from coil-building: using many thin coils to build up the shape of the pot. For most pots, those coils are scraped smooth as they're still wet. But for corrugated pots, those coils are only scraped smooth on the inside. The outside coils are instead pressed using a tool or the potter's thumb to make a patterned, scaled, or woven texture. Corrugation, due to its association with cooking pots, is not typically considered "decoration" by archaeologists, but it creates beautiful and captivating patterns.

Micaceous

Micaceous Bowl with Etched Flowers. Made by Virginia Romero (Taos Pueblo, 1896-1998).

In northern New Mexico, there are golden-red clays with a lot of sparkly mica in them. The mica self-tempers the clay, and creates a lovely shimmering effect when you see the pots in person. There's evidence of polished micaceous pottery being made as early as the 1300s, but it really took off as a popular type of cooking ware in the 1500s-1600s. In this time, it was made primarily by norther Pueblos like Taos, Picuris, and Nambe, but was enthusiastically adopted by the Jicarilla Apache as well, who have strong social ties to those northern Pueblos. Cimarron Micaceous, the handled jar seen above the cut, is a 1600s Apache micaceous pottery style.

Micaceous pottery is still extremely popular with Native potters today. Some of it is as an art form, with many different experiments in structure and style, but some people still swear by cooking in these micaceous clay pots - beans just taste better when cooked in clay instead of metal!

Incised

Taos Incised jar sherd. Northern New Mexico, AD 1050-1300.

Incised ware is SO underappreciated. However I am also biased because for the past three or four summers I have worked on an archaeology project in the Taos area and we find so much of it.

Incised designs are carved into the wet clay. Usually, these are not painted. Incised pottery is very common on the Great Plains, but less so in the Southwest. The Northern Pueblos like Taos and Picuris, however, has long-standing interactions with Plains groups, trading corn and buffalo hides, holding market days together, Picuris and Taos people fleeing the Spanish invasion to live in Kansas with their Apache allies. This is also visible in the sharing of pottery styles in the northern Pueblos, where incised ware is common. Parallel lines that mimic corrugation, chevrons, and herringbone patterns are common.

Plain Smudged

Reserve Plain Smudged, Mogollon Highlands, AD 600-1250.

As I described in my pottery jargon post, "smudging" is a method of getting that shiny black interior during the firing stage. During firing, different levels of oxygen will cause the minerals in the clay to turn different colors. An oxidized environment (high oxygen) turns iron-rich clays red; a recducing atmosphere (restricted oxygen) plus an infusion of carbon turns them black. To smudge a pot, the inside is polished, and then in the firing pit is covered with ash and charcoal. This puts a lot of carbon on the surface, and blocks the oxygen from reaching it. When the pot comes out of the fire, the part that was covered in charcoal will be shiny black. This was another pottery style particularly popular in Mogollon areas.

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

This is a way I was talking about at one point, & glad to see it being put to good use from others beyond my network. Happy (early by a month) Tsagaan Sar to all

0 notes

Text

Interesting Facts About the History of Mica

While many industries use mica in various ways today, few people are aware of what this mineral is. Humanity has known about and used mica for thousands of years. Its continued use proves just how unique and important it is. Keep reading to learn interesting facts about the history of mica and its various uses.

Ancient Origins

People have known about and used mica for hundreds of thousands of years, predating written records. We know that ancient civilizations around the world used mica in various ways. One of the earliest examples we have is cave paintings dating to the Upper Paleolithic era, which stretches from 40,000-10,000 B.C. Ancient people used mica to create white paint.

Uses Through History

Over time, people started using mica in a larger variety of projects. Taos and Picuris Pueblos Native Americans still use mica in their pottery. People in India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh use mica to decorate clay pots as well. In 100 A.D., the Aztecs started using mica as a construction resource when building the Pyramid of the Sun, which is still standing just north of Mexico City. The Padmanabhapuram Palace in India, which was built in the early 1600s, has mica in its colored windows. Mica is also used in traditional Japanese woodblock printmaking, as printers apply it to wet ink so that the ink dries and sparkles.

Modern Uses

While many people still use mica in these traditional ways, such as in pottery and printmaking, new industries have arisen that also use mica. Some of the most common uses of mica today are in the electronics and plastics industries, where mica can act as an insulator or reinforcer, respectively. And proving that there is nothing new under the sun, the paint industry uses mica to brighten the tone of colored pigments and help the paint work better, as it helps prevent chalking.

Some of the most interesting facts about the history of mica are how ancient civilizations used it in such various ways, paving the way for us to continue to use it in the present. This fascinating mineral has allowed humanity to creatively express themselves and build empires for hundreds of thousands of years. As we continue to use it in our electronics and plastics, we continue to develop that legacy.

https://youtu.be/wF8X87lNHwM

Read the full article

1 note

·

View note

Text

Corner Window

Corner Window (Hotel Santa Fe the Hacienda & Spa) — Photo-Artistry by kenneSanta Fe’s Only Native American Owned HotelIn Partnership with The Picuris Pueblo

View On WordPress

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

AERIAL VIEW Copy photograph of photogrammetric plate LC-HABS-GS01-B-1974-308. - Pueblo of Picuris, Vadito Vicinity, Picuris Pueblo, Taos County, NM

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Francisco Duran, Picuris, in Partial Native Dress Near Adobe Wall - Vroman - 1899

15 notes

·

View notes

Photo

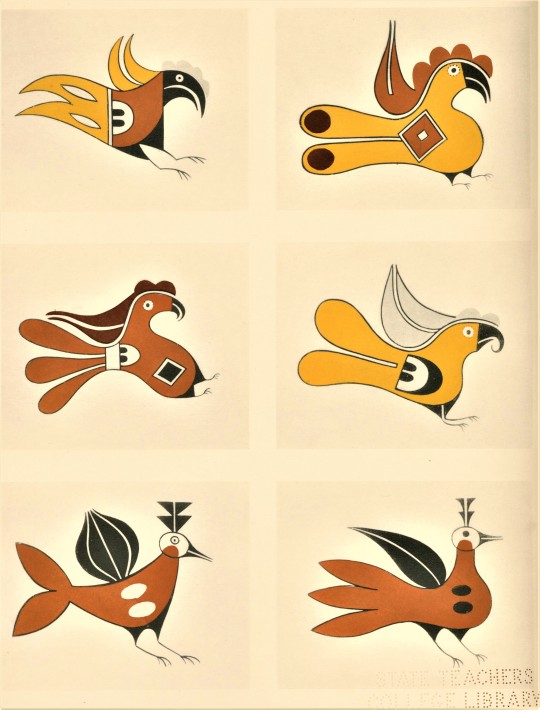

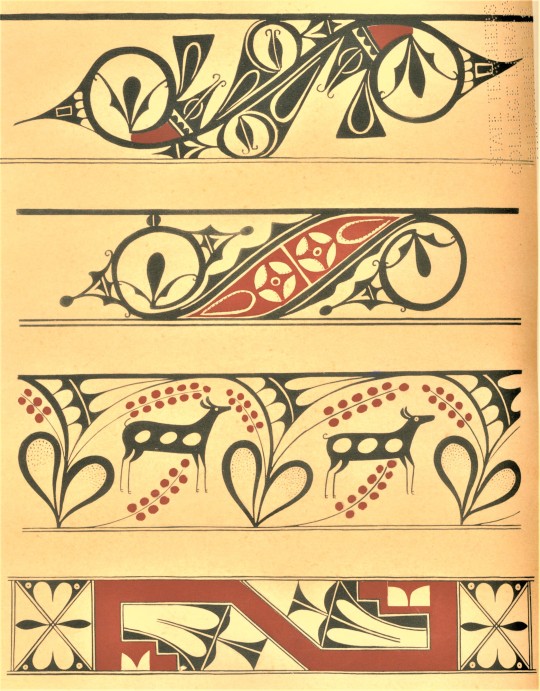

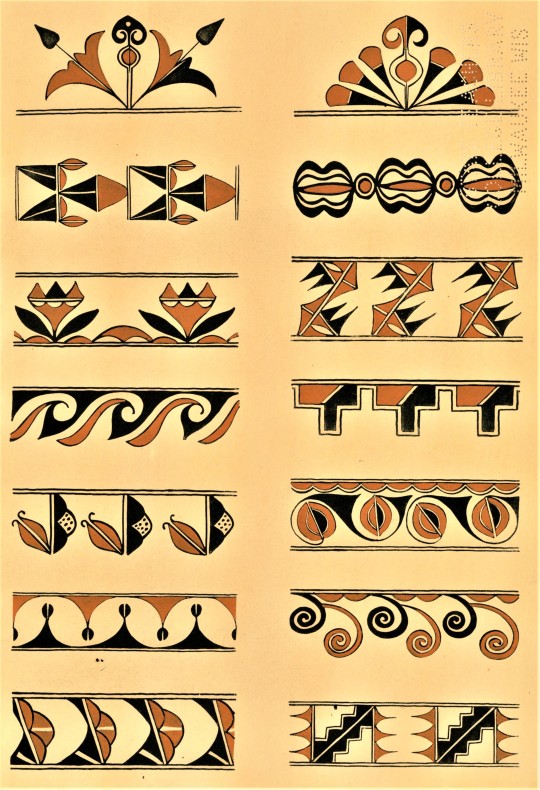

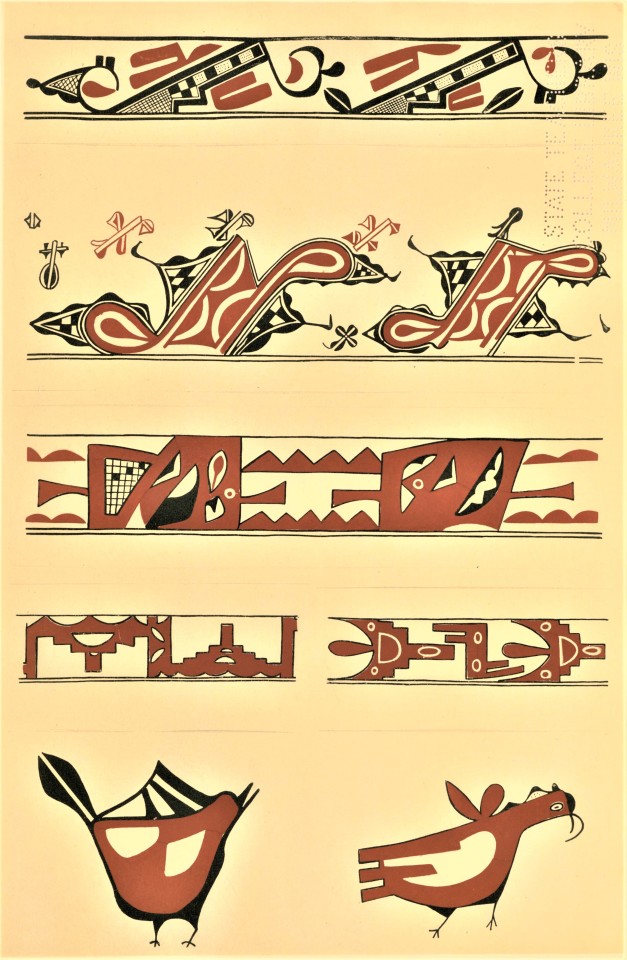

Decorative Sunday

A few weeks ago, our graduate intern Olivia introduced us to the decorative-arts publishing of the somewhat hazy figure of C. Szwedzicki. In that post, Olivia noted that C. Szwedzicki produced 6 titles on Native American Art, the publishing of which was interrupted when the Nice, France, business was seized, either by German Nazis or French Pétainists, and Szwedzicki was shipped off to Poland. Szwedzicki survived the war, and the work on this series was resumed, beginning in 1950.

Today we are showing some plates from one of the titles in that series, the 2-volume Pueblo Indian Pottery by Kenneth M. Chapman, curator of the Indian Arts Fund and the Laboratory of Anthropology in Santa Fe, New Mexico, and published in by Szwedzicki in Nice from 1933 to 1936 in an edition of 750 numbered copies signed by the publisher. The volumes include 50 hand-colored photolithographs drawn by Kenneth Chapman himself after vessels in the collection of the Indian Arts Fund at the Laboratory of Anthropology. The text is in both English and French. Volume I focuses on Taos, Picuris, San Juan, Santa Clara, San Ildefonso, Tesuque, Cochiti, Santo Domingo, and Santa Ana, while Volume II surveys Zia, Acoma, Zuni, and Hopi.

Click on the images to view the captions. If that fails, see the list of plates below the “Keep reading” prompt.

See more of our Decorative Sunday posts here.

The images from top to bottom are:

1.) Acoma water jar, ca 1875-1925. Diameter 11 in./28 cm.

2.) Title page from volume 1.

3.) Conventional bird design from the interior of a food bowl, Sikyatki, Arizona, ca. 1500.

4.) Group of designs from Zuni pottery.

5.) Group of bird designs from Acoma pottery.

6.) Group of designs from antique Zia pottery.

7.) Typical designs from antique San Ildefonso pottery.

8.) Typical designs from antique Santa Ana pottery.

9.) Group of designs from antique and modern Hopi ware.

10.) Acoma bowl, ca. 1875. Diameter 18 in./46 cm.

#Decorative Sunday#decorative arts#decorative plates#Pueblo Indian Pottery#Pueblo Indians#decorative designs#C. Szwedzicki#Kenneth M. Chapman#Indian Arts Fund#Laboratory of Anthropology#photolithographs#lithographs#hand-colored plates

171 notes

·

View notes

Text

Joseph Rael's Sound Peace Chambers

Joseph Rael, whose Tiwa name, Tsluu teh koy ay, given to him as a child at Picuris Pueblo, means "Beautiful Painted Arrow," is widely regarded as one of the great Native American holy men of our time. He was born in 1935 on the Southern Ute reservation to a chief's granddaughter and a Tiwa-speaking Picuris native. At about age 7, shortly before his mother's death, he went to live in Picuris near Taos, NM, where his visionary powers were developed until, at about age 12, he began to assist the village holy man in curing practices.

He was educated both at Santa Fe Indian school and public high school before getting a BA in political science from the University of New Mexico and an MA from the University of Wisconsin-Madison. For a number of years he worked in various capacities in Indian health and social services in both New Mexico and Colorado.

At age 45 he quit his social services job to devote full time to teaching and following his visions wherever they might lead. In 1983 Joseph had the vision to build a Sound Peace chamber, a kiva-like structure where people of all races might gather to chant and sing for world peace and to purify the earth and oceans. He built the first such chamber at his then-home, a trailer park in Bernalillo, NM, and shortly like-minded people began to build Sound Peace chambers in other locations.

At present, Sound Peace chambers have been built around the globe. Writes Joseph, "My vision is that through sound we will bring about peace and other important vibrations. Sound can teach us a way to create without destruction." Meanwhile, Joseph began leading ceremonial dances, based on his visions, with participants from all races and nationalities. "When you dance you are expanding the vibrations of insight and manifestation," he writes. "I created three dances -- the long dance, the sun-moon dances and the drum dance -- for these spiritual gifts."

Joseph teaches that "Every dance, every ceremony, is both for you and for the cosmos." In 1999, Joseph retired from active leadership of the dances he had begun, turning them over to a new generation of his students. Joseph Rael is the author of a number of books, including Being and Vibration, Sound: Native Teachings and Visionary Art and his autobiography, House of Shattering Light. He is also an artist. His paintings, like his ceremonies and teachings, are based on his visions. They have been called "portal" art, because they open a doorway into alternate dimensions of reality. As a Native American elder, Joseph Rael has spoken before the United Nations and addressed a conference of military officers at the Pentagon on the role of the warrior in the modern world.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tres Rios Watershed Coalition Sets Schedule for Forest Restoration Projects

Tres Rios Watershed Coalition Sets Schedule for Forest Restoration Projects

By KAY MATTHEWS

The Tres Rios Watershed Coalition—the Embudo drainage from the Rio Pueblo to the Rio de Las Trampas—was the first of the individual group meetings scheduled by the Enchanted Circle Priority Landscape. As La Jicarita recently reported, the Enchanted Circle, which covers the Sangre de Cristo range between Taos and Colfax counties, was designated one of the highest priority…

View On WordPress

#Camino Real Ranger District#Collaborative Forest Restoration Program#Enchanted Circle Priority Landscape#Picuris Pueblo#Rio de las Trampas Forest Council#Santa Barbara Land Grant#Tres Rios Watershed Coalition

0 notes

Text

Ladder casting twisted shadow on external wall of San Lorenzo Church, an adobe-style structure at the Picuris Pueblo Indian reservation in Northern New Mexico, 2012 - by Terje Langeland, Norwegian/American

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Ceremony in the Atomic Age.”

Marian Naranjo opens the wooden door and steps inside a roughly 15-square-foot adobe house called a buwah tewha, purpose-built for baking buwah, the Tewa people’s first ancestral bread. [...] Naranjo, a member of Santa Clara Pueblo, has invited me into this space [...]. Since April [2019], Naranjo’s organization Honor Our Pueblo Existence [...] have invited women from Santa Clara Pueblo and other Tewa villages into this space every second weekend of each month to “bring back one of our most important lifeways,” the baking of buwah [...]. Pueblo lifeways, things like farming and Tewa language, for example, [...] have mostly been set aside through centuries of genocide and erasure [...] during Spanish colonialism and later American occupation, Naranjo said during one of our early conversations in 2018. [...] “So that was one of the big changes, you know, that came from fences, and ownership, and those kinds of things: capitalism. [...] Before [...] everybody participated in food. Then what came here was you have to go to school, get a degree or graduate, so that you can get a job, to buy a car, to go to the grocery store, so you can eat. [...] It was forced. They couldn’t fight what was coming.” What was coming could be any number of things. [...] Whatever she was referring to, it can [...] be symbolized by the institution Naranjo has spent much of her life fighting against: Los Alamos National Laboratory.

In many ways, Naranjo said, what is now called the Espanola Valley is a place where things happen, but then reverberate throughout the country and the world, like ripples of water on a shoreline.

This phenomenon can be represented [...] [by] the most prominent example [...] the discovery of the atomic bomb in 1945.

“This place is a sacred place and the people who were planted here are still here,” she said, referring to the area that encompasses Santa Clara Pueblo, Ohkay Owingeh and the city of Espanola. “That this is one of the spots where whatever starts here, goes around the world. We know this because of what was last planted in this sacred place: the atomic age. We saw this go around the world. This short, destructive force that’s the total opposite of all of our belief.” [...]

Roxanne Swentzell, a sculptor from Santa Clara Pueblo, was one of the roughly 60 people who helped Naranjo build the two women’s houses for making buwah. [...] “From there, we were learning more about the foods, and one of the foods we re-remembered is the buwah, our traditional ceremonial bread,” Swentzell said. So the duo went to a class in Pojoaque Pueblo where they learned how to make the bread again, and wanted to bring it back to Santa Clara Pueblo. [...] She met Naranjo when Swentzell was in her 20s during a language class. “She struck me as amazing,” Swentzell said of Naranjo. “She speaks from her heart [...].”

Swentzell, who works with clay like Naranjo, said pottery is a common language.

When Marian Naranjo was six or seven years old, her father drove her up the hill, where she saw the gate to Los Alamos. “There was this tower, with guys standing up there with machine guns,” she would later tell a documentary filmmaker. “I wasn’t really scared, only that it was a time that I was born into.” [...] She graduated [...] in 1968. That summer, she worked as an intern for the Lab, going up and down the hill daily to work in dosimetry, measuring doses of radiation. [...]

Through her work with Communities for Clean Water and Amigos Bravos, she helped establish the individual industrial stormwater permit which, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, is the strongest in the nation. The permit was issued Nov. 1, 2010 as part of the settlement of the Clean Water Act lawsuit, and requires the Laboratory to meet stormwater management requirements at more than 400 legacy sites. Joni Arends, co-founder and executive director of Concerned Citizens for Nuclear Safety (CCNS), said she met Marian when she returned to the group in 1998. At the time, Marian was working with the group to settle a lawsuit it had filed against the Laboratory because it was releasing radioactive material into the air, a violation of the Clean Air Act.That settlement resulted in funding for the Community Radiation Education Project, which paid for educational programming in pueblos about the radioactive contamination. [...] Arends said Marian gathered 144 pueblo elders for a meeting at Picuris Pueblo to reach a consensus to protect the sacred area on which the Lab was built.

-----

Text, images, and captions published by: Austin Fisher. “Ceremony in the Atomic Age.” Women of Distinction series. Rio Grande Sun. 27 July 2019. Updated 12 March 2020.

383 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Native American Sterling Silver Blue Ridge Turquoise Oval Pendant For Women Native American Sterling Silver Blue Ridge Turquoise Oval Pendant For Women. Measure 7/8" X 1 5/8" (Inc Bail) and weighs 9.3 grams. **Pendant Only. Navajo Pearl Beads 4 mm Necklace Sold Separately.** (MTPN86HO95) *************************** *** DM for details *** *************************** Authentic Native American Handmade Jewelry *************************** ✨**Take a look at our shop**✨ Discover our Uniquely Beautiful Collection of Vintage and Native American Jewelry here: 👇⬇️ https://mountainofjewels.com/ #mountain_of_jewels #handmadejewelry #southwestjewelry #nativejewelry, #vintagejewelry #southwesternstyle #sterlingsilver #oldpawn #tradingpost #instausa #navajosilversmith #affordablejewelry #rodeojewelry #southwestlook #cowgirllook #cowgirlstyle #westernwear #cowboylook #quarterhorses #santafestyle #newmexicotrue #turquoise #bohostyle #ranchlifestyle #bestofthesouthwest #shopsmall *************************** *** DM for details *** *************************** (at Picuris Pueblo, New Mexico) https://www.instagram.com/p/CmCXJdFpBg3/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#mountain_of_jewels#handmadejewelry#southwestjewelry#nativejewelry#vintagejewelry#southwesternstyle#sterlingsilver#oldpawn#tradingpost#instausa#navajosilversmith#affordablejewelry#rodeojewelry#southwestlook#cowgirllook#cowgirlstyle#westernwear#cowboylook#quarterhorses#santafestyle#newmexicotrue#turquoise#bohostyle#ranchlifestyle#bestofthesouthwest#shopsmall

0 notes

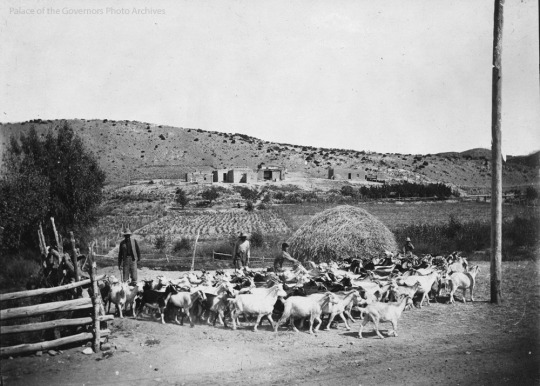

Photo

Threshing with goats, Picuris Pueblo, New Mexico

Photographer: Ed Andrews

Date: 1915 - 1920?

Negative Number: 015123

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why not admit

there’s no place our love will be easy again,

however far we drive into the mountains;

why not say it here, where the air

is heavy with flies, where nothing is trying

very hard to be graceful

or even kind. But maybe it is kindness, after all,

that keeps us from talking; we walk side by side,

tear the soft bread in two and share it.

- Kim Addonizio from the poem Crafts Fair, Picuris Pueblo | Tell Me

#kim addonizio#poem#heartbreak#love#heart#life#relationship#poetrydaily#poemsociety#poemporn#literature#words

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

📷 Featured Photographer 📷 Meredith Houx Remiger, aka @mahoux23 - "On the high road 💙 #landofenchantment" ⬇ Picurís pueblo was once one of the largest Tiwa pueblos, but today it is one of the smallest, with about 1,801 tribal members. Their language, Tiwa, is part of the Tanoan language group. (at Picuris Pueblo, New Mexico) https://www.instagram.com/p/B7T_x8CHAFi/?igshid=8k6fk97jnbjq

10 notes

·

View notes