#quai cronstadt

Text

Toulon. Le Quai Cronstadt. Carré du Port. Courrier de Corse. 1912

#toulon#quai cronstadt#carré du port#1910s#1912#Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region#Var department#french riviera#mediterranean coast#côte d'azur

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Exhaustive list of Valjean and Vautrin references in the diss so far

below the cut!

Valjean:

An 1866 Jesuit polemic against romanticism entitled Le vandalisme littéraire evokes sunlight in this curious denunciation of Jean Valjean: “C’est le sombre héros de cette sombre histoire, le forçat sur lequel on a appelé votre commisération, l’homme qui a usé le soleil du bagne.” The story and its protagonist are dark not in spite but because of the fact that the latter has “usé” (used, or worn out?) the sun which is not only associated with, but in a sense constitutive of, the bagne. Valjean was, of course, in Toulon—not Brest or Rochefort. Léon Faucher goes so far as to describe the bagne of Toulon as being “sous un ciel vraiment africain.” In Le dernier jour d’un condamné, the protagonist says that he would prefer the bagne to the guillotine, even for life, because at least a forçat “marche encore; cela va et vient; cela voit le soleil.”

The sun is not inherently tied to the bagne in this case, since it has been a leitmotif throughout the novella; however, it comes very à propos in a reference to the forçats which the condamné has seen earlier, since they were headed for Toulon, which is intimately linked to the sunlight. It is indeed Toulon that the condamné pines for, even if he does not know it himself; if he were to be sent to Brest, his days would instead be filled with a rain not unlike the one that falls on the day of his execution, or of the cadène’s departure. Similarly, Jean-Isidore Rous would almost certainly not have described Valjean as “l’homme qui a usé le soleil du bagne” if he had not been in Toulon.

Unlike Gustave, Valjean’s inability to appreciate “[le] soleil, ni [les] beaux jours d’été, ni [le] ciel rayonnant, ni [les] fraîches aubes d’avril” is not due to his aesthetics, but it nonetheless shows the limits of natural beauty in a bagne setting. “La nature visible existait à peine pour lui,” the narrator tells us; “Je ne sais quel jour de soupirail éclairait habituellement son âme.”

The bagne occurs as frequently in récits de voyage whose authors pass through Toulon, Brest or Rochefort as it does in exposés and reports that take it as a main subject; almost in spite of themselves, travelers saw the institution and its inmates as a tourist attraction, and were perhaps correct to do so––just as Jean Valjean was correct to fear especial infamy in Toulon because of his having being mayor in Montreuil-sur-Mer.

Another Jesuit, Jean-Isidore Rous, so wished to keep the bagnard at arm’s length that he could not even countenance an ex-convict between the pages of a book. Jean Valjean qua a hero and protagonist, he vituperates in the Les Misérables-focused chapter of the anti-Romantic tract Le vandalisme littéraire, is both an impossibility and an intolerable affront: “L’apothéose de Jean Valjean est la plus grande insulte qui ait jamais été faite à la société. Lavons-nous de cette boue comme nous pourrons, nous n’en aurons pas moins été salis. Type hideux d’une dépravation qui prend sa source dans la plus profonde immoralité, Jean Valjean secoue les plis de son manteau sur nous tous qu’il méprise. Il n’a pour nous, qui l’avons frappé avec les armes de notre justice, que des malédictions et des anathèmes.”

Even Victor Hugo, whose entire thesis hinged on the humanity of the downtrodden and degraded, emphasizes Valjean’s bestial and mechanical nature: hard labor transforms “peu à peu, par une sorte de transfiguration stupide, un homme en une bête fauve, quelquefois en une bête féroce,” and Valjean cannot help but follow the impulse to escape whenever the opportunity presents itself, “comme le loup qui trouve la cage ouverte.” Similarly, more than a beast of burden, Valjean is a human jack––nicknamed “Jean-le-Cric,” and able in a pinch to take the place of load-bearing statuary: “Une fois, comme on réparait le balcon de l’hôtel de ville de Toulon, une des admirables cariatides de Puget* qui soutiennent ce balcon se descella et faillit tomber. Jean Valjean, qui se trouvait là, soutint de l’épaule la cariatide et donna le temps aux ouvriers d’arriver.”** In context, these images serve as an indictment of society and of the penal system rather than of Valjean himself, but they still frame the victim as something less––but also sublimely more––than human.

*Footnote: These sculptures––which, being masculine figures who show apparent effort, are technically atlantes rather than caryatids––still exist, although the building to which they were originally attached does not. Much like the stained glass of Chartres Cathedral, they were removed from the Hôtel de Ville in anticipation of bombing during WWII and stored in a less exposed place. After the war, a new mairie (now a “mairie d’honneur,” with the real mairie moved across the street) was built in the same spot on what is now the Quai Cronstadt, and the atlantes/caryatids reattached. They and the original building and balcony are visible in the backgrounds of period paintings such as Joseph Vernet’s 1755 Troisième vue de Toulon, vu du Vieux Port, prise du du côté des magasins aux vivres (see Chapter 2 for a discussion of the relationship between forçats and the naval, urban, and natural landscape).

** Footnote: Émile Bayard furnished an illustration for this scene whose title, “Les deux cariatides,” emphasizes the equivalence between Valjean and this load-bearing sculpture. According to the tour guide and local historian Jean-Pierre Cassely, the two statues are allegorical, named “La Force” and “La Fatigue” but nicknamed “Mal au Dos” and “Mal aux Dents.” In Bayard’s illustration, Valjean is shown to be holding up a slightly larger-than-life-sized version of La Force.

In a sense, it is the healing, and not the trauma, that makes a brand truly permanent—scar tissue is a deeper structural change than an open wound, and thus the convict’s body is complicit in his degradation. The limp was a similar kind of adjustment, an acceptance of the new state of things. Of course, the chain existed for its own sake in a way that a branding iron did not, so the leg-dragging effect blurs the lines between a purposeful marking and an unintentional (but useful) side effect. Either way, the convict begins as a tabula rasa and ends indelibly sullied by his ordeal, having acquired a contaminating knowledge against his will. That is why it is so poignant that, while confessing his convict past to Marius towards the end of Les Misérables, Jean Valjean declares, “avec un accent inexprimable, ‘Je traîne un peu la jambe. Vous comprenez maintenant pourquoi.’” He is exposing himself completely to his son-in-law’s scorn, showing him a visible proof of his permanent degradation—after Toulon, even the way he walks is impure.

Joseph Méry uses the bonnet vert as sort of secondary synecdoche for hard labor for life, after the more obvious one of the casaque rouge for hard labor in general: “Ne savez-vous pas que l’irritation d’un moment, dans vos villes d’orages,” asks the convict protagonist of Le Bonnet Vert, “peut changer du soir au matin votre feutre noir contre un bonnet vert?” Hugo performs a similar maneuver in Les Misérables, as Jean Valjean is first identified as a convict because of his casaque and then as a convict for life because of his bonnet vert: “Tout à coup, on aperçut un homme qui grimpait dans le gréement avec l’agilité d’un chat-tigre. Cet homme était vêtu de rouge, c’était un forçat; il avait un bonnet vert, c’était un forçat à vie.”

He then adds a description of Valjean’s hair––an additional layer which is altogether outside the bagne’s symbolic system and is revealed in the same moment he is freed of the bonnet––and immediately decodes it as well: “Arrivé à la hauteur de la hune, un coup de vent emporta son bonnet et laissa voir une tête toute blanche, ce n'était pas un jeune homme.” Thus a bonnet vert denotes a lifer while a casaque rouge denotes a convict alone, and together with Valjean’s white hair they form the syntagm “old convict for life”*; these declarations set boundaries or expectations (he is unfree and thus impotent, he is old and therefore incapable) which are shortly transcended through grace and Valjean’s own prodigious ability.

*Footnote: It should be noted that Valjean’s clothing in the passage is both particular to its historical moment and in line with a partially contradictory gestalt imaginary. Statements like “all convicts wearing green caps are forçats à vie, all forçats à vie wear green caps, the casaque is entirely red, etc.” are incorrect when compared to the entirety of the historical record, but correct on a level that serves the story.

Like everything else, the actual shoes varied over time and from bagne to bagne; they could be wooden sabots, but they could also be souliers ferrés. In Les Misérables, Valjean, in a free indirect discourse, dreads the coming hardship of wearing such shoes (with no socks, a detail that may not be entirely accurate): “Si encore il était jeune! Mais vieux, être tutoyé par le premier venu, être fouillé par le garde-chiourme, recevoir le coup de bâton de l’argousin, avoir les pieds nus dans des souliers ferrés !”

Hugo evokes the cadène in two of its stages in Les Misérables: first the ritual of ferrage in the courtyard of Bicêtre, a solemn and tragic moment for Valjean in 1796; then the carnivalesque spectacle, in 1831, of the journey itself, which is witnessed both by an older Valjean (who has a flashback to 1796) and by Cosette (who is both disturbed and curious). This is the exact opposite of the treatment it is given in Le Dernier jour d’un condamné, where the initial ferrage is carnivalesque and the subsequent departure of the carts is a somber, rainy affair. In both cases, it is sunlight which stirs the convicts to action and provokes the grotesque: “Un rayon de soleil reparut. On eût dit qu'il mettait le feu à tous ces cerveaux. Les forçats se levèrent à la fois, comme par un mouvement convulsif [...] Ils tournaient à fatiguer les yeux. Ils chantaient une chanson du bagne”; “Brusquement, le soleil parut; l'immense rayon de l'orient jaillit, et l'on eût dit qu'il mettait le feu à toutes ces têtes farouches. Les langues se délièrent; un incendie de ricanements, de jurements et de chansons fit explosion.”

In Les Misérables, Valjean reacts with uncharacteristic joy when called “monsieur” by Bishop Myriel because “l’ignominie a soif de consideration”; related to the desire for consideration is a need for individuation.

A footnote: After his release from Toulon, a half-asleep Valjean is obsessed by the image of a fellow-convict’s checkered suspender: “[E]t puis il songeait aussi, sans savoir pourquoi, et avec cette obstination machinale de la rêverie, a un forçat nomme Brevet qu'il avait connu au bagne et dont le pantalon n'était retenu que par une seule bretelle de coton tricote. Le dessin en damier de cette bretelle lui revenait sans cesse à l'esprit.” The memory of this suspender allows Valjean to identify Brevet during Champathieu’s trial and to prove that he had known him in prison (and thus that he, not Champmathieu, is Jean Valjean): “Te rappelles-tu ces bretelles en tricot à damier que tu avais au bagne ?” Such is the importance of the detail which serves to identify and individualize the forçat.

The concept of the matricule number is mise en roman to particularly great effect in Les Misérables. Valjean’s prison number, his identité matriculaire so to speak, is woven into his character and narrative arc, and within the universe of the novel, form a traceable path through the bagne’s paperwork just as his aliases follow him through the twists and turns of the plot. Were he real, his second matricule entry would read “Jean Valjean, dit Madeleine,” and his first entry would forward the reader to his new one, hypertextually: “revenu sous le numéro 9430.”

Jean Valjean’s return to Toulon and arrival in Montfermeil are both framed as numerical substitutions or transformations—the first is a simple change of name and state, and the second an act of prestidigitation in which the same number magically takes on new powers. The chapter in which the reader is informed that Valjean is once more a prisoner (“Le 24601 devient le 9430”), and that in which he is revealed to be Cosette’s mysterious benefactor (“Le numéro 9430 reparaît et Cosette le gagne à la loterie”), share a number of structural parallels. Both refer to Valjean’s prison number (and Valjean as number); one is the first chapter of the sub-volume in which it appears (Livre Deuxième, Le Vaisseau l’Orion) while the other is the last chapter of the following sub-volume (Livre Troisième, Accomplissement de la Promesse Faite à la Morte), thus bookending the contents of both; and the chapters themselves consist of short, dialogue-free recapitulations, both opening with a drastic update regarding Valjean’s coordinates vis a vis freedom and captivity (“Jean Valjean avait été repris”) or life and death (“Jean Valjean n'était pas mort”).

“Le 24601 devient le 9430” introduces a setback that later turns out to be the setup for remarkable, even miraculous events. The reader sees Valjean apprehended (“repris”) and misapprehended as well (“Il a été établi, par l’habile et éloquent organe du ministère public, que le vol avait été commis de complicité, et que Jean Valjean faisait partie d’une bande de voleurs dans le Midi”), even being sentenced to death before being granted a royal commutation. He is condemned to spend the rest of his life in the bagne and his reintegration into the system seems to both proclaim and ordain this, his new address within the bureaucracy (“Jean Valjean changea de chiffre au bagne. Il s’appela 9430”) implying an existential imprimatur similar to the “pouvoir de faire ou, si l'on veut, de constater des damnés” that, according to Hugo, Javert and other “esprits extrêmes [...] attribuent à la loi humaine.” The inhabitants of Montreuil-sur-Mer, too, are the victims of this (con)damnation, as the sentence immediately following Valjean’s immatriculation shows: “Du reste, disons-le pour n’y plus revenir, avec M. Madeleine la prospérité de Montreuil-sur-Mer disparut ; tout ce qu’il avait prévu dans sa nuit de fièvre et d’hésitation se réalisa ; lui de moins, ce fut en effet l’âme de moins [emphasis in original]” (citation). Cosette would be yet another victim if it were not for Valjean’s determination and near-superhumanity. While coming to the aid of a sailor, he appears to drown, only to be resurrected in “Le numéro 9430 reparaît et Cosette le gagne à la loterie.”

The reader can guess, of course, that the stranger in “Cosette côte à côte dans l’ombre avec l’inconnu,” the mysterious “homme à la redingote jaune,” is none other than Jean Valjean, just as they were never really in doubt about the identity of Monsieur Madeleine; nonetheless, it is this chapter that names him, and in so doing closes the file that was opened with “Le numéro 24601 devient le numéro 9430.” Furthermore, the comparison to a winning lottery number underscores the miracle of Valjean’s escape, and ties what is otherwise a dehumanizing anti-name to fate and fortune in a positive sense. It is qua 9430 that Cosette’s rescuer (re)appears, both in contrast to a name, and in contrast to 24601, whose escape attempts were never successful. Madeleine desires to save Cosette; 9430 accomplishes the deed.

Vautrin:

Balzac and the penal reformer Benjamin Appert share Alhoy’s assessment of Rochefort’s lethality: in Splendeurs et misères des courtisanes, Vautrin tells his accomplice and lover Théodore Calvi, alias Madeleine, “S’ils nous ont déjà ferrés pour Rochefort, c’est qu’ils essaient à se débarrasser de nous”––a sentiment shared by the narrator: “[C]ette superbe évasion avait eu lieu dans le port de Rochefort, où les forçats meurent dru, et où l’on espérait voir finir ces deux dangereux personnages”––and Appert writes, “La mortalité est plus considérable à Rochefort que dans les autres bagnes. Mais on ne doit attribuer ce funeste résultat qu’au climat, et aux changemens fréquens de la température, puisque, pour les hommes libres, la même différence existe entre la mortalité de Rochefort, et celle de Toulon, Brest et Lorient.”

Accouplement exposed the convict to very real risks of physical and sexual abuse and/or assault, but the specter of homosexuality preoccupied contemporary writers even in the absence of violence. Balzac appears to have been interested in the possibilities of consensual or semi-consensual accouplement (in all senses of the word); in between the events of Le Père Goriot and Illusions Perdues, Vautrin is sent to the bagne of Rochefort where he grows close to Théodore “Madeleine” Calvi, a young and handsome murderer whose companionship he “bought” from the administration, having bribed those in charge to chain them together. In addition to the obvious contact, the chain also engendered closeness between Vautrin and Calvi in indirect ways. In Splendeurs et Misères des courtisanes, Bibi-Lupin cites the quality of the patarasses (see page number) Vautrin made for Calvi as proof of his affection for his friend and lover: “Théodore Calvi, ce Corse, est le camarade de chaîne de Jacques Collin; Jacques Collin lui faisait au pré, m’a-t-on dit, de bien belles patarasses…” (47).

Anthelme Collet is probably the most famous convict memoirist after Vidocq; like the latter, he also served as an inspiration for Vautrin, but unlike him, he wrote his memoirs from the bagne of Rochefort, where he ended his life.

A generic workmen or bourgeois made for a viable disguise––Vidocq had success dressing as a sailor during his escape from Brest––but it could also be useful to impersonate someone more intimately affiliated with the system. Alhoy writes in Les Bagnes: Rochefort of a convict who managed to escape by posing as a pharmacist with the aid of a sheet: “Enchaîné dans un lit à l'hôpital, objet d'une surveillance spéciale, il coupe sa chaîne, s'affuble d'un drap qu'il tourne autour de son corps comme un tablier de pharmacien, cache sa tête sous une profonde casquette, passe au bout de la salle entre les deux lits où les gardes-chiourmes sont assis éveillés [...] franchit le mur, et jouit de la liberté qu'il a acquise par un trait de hardiesse peu commun.” Likewise, in what the narrator of Splendeurs et misères des courtisanes describes as a “superbe évasion,” the fictional Vautrin and Madeleine abscond together from Rochefort in 1820 by means of an ingenious ruse in which it is only necessary for one one person, Vautrin, to appear “legitimate”: “il était sorti déguisé en gendarme et conduisant Théodore Calvi marchant à ses côtés en forçat, mené chez le commissaire” (citation). The second escapee can, and indeed must, remain a convict, and that is what makes this particular escape one of Vautrin’s “plus belles combinaisons.”

Born in 1799 in Landreville where he served at one point as a notary clerk, Simon was a law student in Paris at the time of his 1823 arrest for burglary and forgery, and one can easily imagine him driven by the same sort of money troubles that cause Lucien de Rubempré to attempt suicide at the end of Illusions Perdues—but with no Vautrin to save him, as the future criminal mastermind had also done for his first love, the forger Franchessini.

A footnote: This is the juridico-historical context of Balzac’s so-called “Histoire des Treize” (La Fille aux yeux d’or, Ferragus, La Duchesse de Langeais) and “Trilogie de Vautrin” (Le Père Goriot, Illusions Perdues, Splendeurs et misères des courtisanes). Vautrin’s brand, TF on the right shoulder, corresponds to the provisions of the 1810 code; as Geoff Woollen notes in “Brand Loyaute in Balzac Criticism,” the phrase “les pauvres diables avec T.F. sur l'épaule” refers specifically to those condemned for forgery (as was Vautrin, wrongly), and not simply forçats in general. It must be noted as well, as Woollen does, that Vautrin’s brand does not mean “travaux forcés”; the T alone represents both words, and the F means “faussaire.” Forgery was apparently another one of the conditions under which a prisoner could find himself branded with a T (as opposed to a TP), as the matricules are replete with TFs. Note as well that a forger sentenced to hard labor for life would be branded TPF and not TFP; contrary to popular belief, including Victor Hugo’s, there is no such thing as a TFP brand.

Both:

To evoke the bagne was to evoke the sea; when the narrator tells us, during Valjean’s first appearance in Les Misérables, that he has come “[d]u midi. Des bords de la mer peut-être”, this is a hint that he is a forçat in much the same way as Vautrin’s disclosure to Rastignac that he has been “dans le Midi” in Le Père Goriot.

While self-fashioning on paper could serve many purposes, the convict’s material mastery of his visual identity had at least one eminently practical end: disguise for the express purpose of escape. The third convict witness against Champmathieu-as-Valjean, Chenildieu, is identified by Valjean-as-Madeleine because of a palimpsest of scars in the same way as Brevet was identified by his suspender(s) and Cochepaille by his tattoo: “Chenildieu, qui te surnommais toi-même Je-nie-Dieu, tu as toute l’épaule droite brûlée profondément, parce que tu t’es couché un jour l’épaule sur un réchaud plein de braise, pour effacer les trois lettres T.F.P., qu’on y voit toujours cependant.” His reasoning for trying to efface his brand is ambiguous; it may have been to aid in an escape attempt (Vautrin similarly disfigures his back as part of his transformation into Carlos Herrera, determined never again to be undone by the brand on his shoulder as he was in Le Père Goriot), or he may simply have resented having to carry around a permanent reminder of his sentence even in prison. These dimensions, of course, are not mutually exclusive; just like the casaque or the irons, the brand had both a symbolic and a practical function, and this duality is reflected in the desire to escape it.

23 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Restaurant Le Calypso 345 quai Cronstadt 83000 Toulon Tél 04 94 15 60 18 Nos restaurateurs ont du talent! #lecalypso #restaurantlecalypso #lecalypsotoulon #restauranttoulon #lesvitrinesdetoulon #commercestoulon #toulonnais #parcequetoulon #villedetoulon #welcomepaca #creditphotomarcelmuller #restaurant #restaurateur #chefcuisine #chefcuisinier #chefcuisto #tripadvisor #jaimetoulonetsaregion #commercesdetoulon #portsradetoulon #portdetoulon #regionsud #provencealpescotedazur (à Le Calypso) https://www.instagram.com/marcel_muller_toulon/p/BweoCH7n3-y/?utm_source=ig_tumblr_share&igshid=i3gppmried9h

#lecalypso#restaurantlecalypso#lecalypsotoulon#restauranttoulon#lesvitrinesdetoulon#commercestoulon#toulonnais#parcequetoulon#villedetoulon#welcomepaca#creditphotomarcelmuller#restaurant#restaurateur#chefcuisine#chefcuisinier#chefcuisto#tripadvisor#jaimetoulonetsaregion#commercesdetoulon#portsradetoulon#portdetoulon#regionsud#provencealpescotedazur

0 notes

Photo

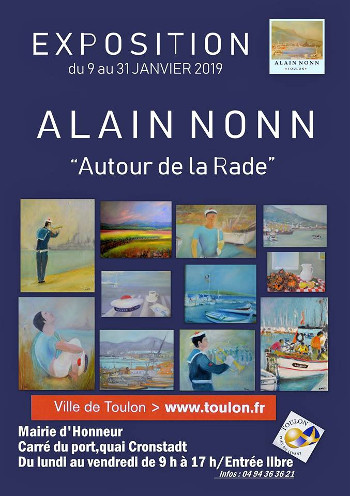

Alain NONN exposition “Autour de la Rade” Exposition du peintre provençal Alain NONN qui se déroulera à la mairie d'honneur- Quai Cronstadt - à Toulon du 9 janvier au 31 janvier 2019.

0 notes

Photo

Toulon. Le Quai Cronstadt. Carré du Port. Courrier de Corse. 1912

1 note

·

View note