#rather than being like. yeah so actually the fault here lies with the billion dollar industries actually.

Text

the thing is there's like, a point of oversaturation for everything, and it's why so many things get dropped after a few minutes. and we act like millennials or gen z kids "have short attention spans" but... that's not quite it. it's more like - we did like it. you just ruined it.

capitalism sees product A having moderate success, and then everything has to come out with their "own version" of product A (which is often exactly the same). and they dump extreme amounts of money and environmental waste into each horrible simulacrum they trot out each season.

now it's not just tiktokkers making videos; it's that instagram and even fucking tumblr both think you want live feeds and video-first programming. and it helps them, because videos are easier to sneak native ads into. the books coming out all have to have 78 buzzwords in them for SEO, or otherwise they don't get published. they are making a live-action remake of moana. i haven't googled it, but there's probably another marvel or starwars something coming out, no matter when you're reading this post.

and we are like "hi, this clone of project A completely misses the point of the original. it is soulless and colorless and miserable." and the company nods and says "yes totally. here is a different clone, but special." and we look at clone 2 and we say "nope, this one is still flat and bad, y'all" and they're like "no, totally, we hear you," and then they make another clone but this time it's, like, a joyless prequel. and by the time they've successfully rolled out "clone 89", the market is incredibly oversaturated, and the consumer is blamed because the company isn't turning a profit.

and like - take even something digital like the tumblr "live streaming" function i just mentioned. that has to take up server space and some amount of carbon footprint; just so this brokenass blue hellsite can roll out a feature that literally none of its userbase actually wants. the thing that's the kicker here: even something that doesn't have a physical production plant still impacts the environment.

and it all just feels like it's rolling out of control because like, you watch companies pour hundreds of thousands of dollars into a remake of a remake of something nobody wants anymore and you're like, not able to afford eggs anymore. and you tell the company that really what you want is a good story about survival and they say "okay so you mean a YA white protagonist has some kind of 'spicy' love triangle" and you're like - hey man i think you're misunderstanding the point of storytelling but they've already printed 76 versions of "city of blood and magic" and "queen of diamond rule" and spent literally millions of dollars on the movie "Candy Crush Killer: Coming to Eat You".

it's like being stuck in a room with a clown that keeps telling the same joke over and over but it's worse every time. and that would be fine but he keeps fucking charging you 6.99. and you keep being like "no, i know it made me laugh the first time, but that's because it was different and new" and the clown is just aggressively sitting there saying "well! plenty of people like my jokes! the reason you're bored of this is because maybe there's something wrong with you!"

#this was much longer i had to cut it down for legibility#but i do want to say i am aware this post doesnt touch on human rights violations as a result of fast fashion#that is because it deserves its own post with a completely different tone#i am an environmental educator#so that's what i know the most about. it wouldn't be appropriate of me to mention off-hand the real and legitimate suffering#that people are going through#without doing my research and providing real ways to help#this is a vent post about a thing i'm watching happen; not a call to action. it would be INCREDIBLY demeaning#to all those affected by the fast fashion industry to pretend that a post like this could speak to their suffering#unfortunately one of the horrible things about latestage capitalism as an activist is that SO many things are linked to this#and i WANT to talk about all of them but it would be a book in its own right. in fact there ARE books about each level of this#and i encourage you to seek them out and read them!!! i am not an expert on that i am just a person on tumblr doing my favorite activity#(complaining)#and it's like - this is the individual versus the industry problem again right because im blaming myself#for being an expert on environmental disaster (which is fucking important) but not knowing EVERYTHING about fast fashion#i'm blaming myself for not covering the many layers of this incredibly complicated problem im pointing out#rather than being like. yeah so actually the fault here lies with the billion dollar industries actually.#my failure to be able to condense an incredibly immense problem that is BOOK-LENGTH into a single text post that i post for free#is not in ANY fucking way the same amount of harm as. you know. the ACTUAL COMPANIES doing this ACTUAL THING for ACTUAL MONEY.#anyway im gonna go donate money while i'm thinking about it. maybe you can too. we can both just agree - well i fuckin tried didn't i#which is more than their CEOs can say

15K notes

·

View notes

Text

Don't let the NCAA off the hook for Zion Williamson's exploitation

Zion Williamson’s (thankfully minor) injury on Wednesday night launched a flurry of activity from the hot-take industry. There were the obvious ones (in which I participated) like “gosh, I hope Zion Williamson has loss of value insurance.” And then less obvious ones like “isn’t it an outrage that NCAA rules prohibit Duke from providing that insurance with Duke’s own money (they have to use a special NCAA fund and if that’s empty, no go).”

These were generally pro-athlete and more or less correct.

But the worst of the bunch, the absolutely most suit-sniffing, barely-whisper-truth-to-power-and do-so-while groveling sort of take is the “this is not the NCAA’s fault, not at all” approach.

The NCAA itself took this approach, because of course they would.

https://twitter.com/NCAA/status/1098995124741332992

https://twitter.com/NCAA/status/1098995126117064705

So if you are a journalist, and a billion dollar industry claims to have no role whatsoever in denying athletes their market-rate of compensation, you have a choice. You can dig in and see whether that’s true, a bad spin of a barely true thing, or a bald-faced lie. Or you can just adopt that approach, more or less un-researched. Unfortunately, the latter was all too common among the hot-take sports crowd.

But besides these sorts of journalists being complicit in the exploitation of athletes by perpetuating the propaganda of the NCAA, here’s why it’s also just plain false that the “real problem” is the NBA/NBPA rule known as one-and-done. It's important to recognize that while many parties are arrayed against the economic welfare of athletes, when people say this is all the NBA's fault, it's missing the crux of the issue to focus on a side effect.

First, the NCAA is not telling the truth when it claims to have nothing to do with one-and-done. One-and-done is a legally validated rule, tested in the courts through the NFL equivalent rule (which is basically three-and-done). That rule was declared illegal by a federal court in 2003, but the NFL appealed and had the ruling reversed. During the appeals process, the NCAA decided to inject itself into the legal process. It could have stayed neutral. Or it could have supported athletes’ rights to go to the NFL and the NBA whenever they want. And if they had done that then I guess I’d agree that they were not at all responsible for one-and-done. But they did not do that. Instead, what they did was actively tell the courts that college sports NEEDED rules like one and done, and please do not make them illegal.

Don’t believe me? I’ve got receipts.

On April 12, 2004, the NCAA filed what is known as an “Amicus Brief” – a “Friend of the Court” statement where a party that is not a part of the lawsuit nevertheless advises the Court what it thinks. Sometimes courts ask for amicus briefs, to get a sense of what the ramifications of a decision might be. Other times, parties just volunteer them. Here’s what the NCAA told the court:

If you can’t read through the legalese, let me translate for you: Please make it legal for the NFL (and any other league like the NBA) to tell 18 year olds they cannot play professionally. If you don’t, we might lose our best athletes unless we pay them and that would really suck.

And so, with this advice from the NCAA in hand, the appeals court struck down the ruling that three-and-done (and other rules like it) was illegal, and declared it totally legal for a league to collectively bargain with a union to make rules like one-and-done.

So that’s how false it is to say the NCAA had nothing to do with one-and-done. Nothing to do with it other than going out of its way to tell the court that made one-and-done illegal that it ought to make it legal, and that the future of the NCAA hinged critically on making rules like one-and-done permissible.

So fast forward to today, and the NBA and the players’ union, the NBPA, have a valid collective bargaining agreement (a CBA in the labor law jargon) that says you must be one year removed from high school to play in the NBA. Like it or not, the law has blessed this. And yes, the NBA and NBPA can change this rule (and in my view should change it) but (1) it is the subject of actual bargaining between owners and athletes, and thus (2) it is a legal rule, and of course (3) the NCAA went out of its way to make it legal.

But more importantly, this NBA/NBPA is not the main reason that college athletes are being exploited economically. Far more harmful to the athletes, both for those who would have gone to the NBA directly from college and those who might never play in the Association at all, are the NCAA rules themselves, the ones that say schools cannot compete for athletes using payments above a fixed level, with that level equal to a scholarship plus $2,000 to $6,000 dollars in cash.

Note – I am not saying college athletes don’t get paid at all – quite the opposite. They are paid. They get a value in the form of a scholarship and on top of that they get paid in cash, around $3,500 a year on average. What I am saying is they are not paid what the market would pay them, if schools like Duke didn’t agree, every single year, with schools like Kentucky that they will not compete for talent like Zion Williamson with the full vigor of a real, uncapped market.

And unlike the sort of caps the NBA and NBPA collectively bargain, the NCAA cap is not bargained at all. Rather, one side of the equation – management, in the form of the schools and conferences that make up the NCAA – colludes among itself and presents the price cap to athletes as a take-it-or-leave-it offer by a monopolist.[1] Which, on its face, is an anticompetitive act, suppressing the payment that thousands of athletes would get without the cap.

Don’t believe me? Well, let’s remember back all the way to 2015, when an appeals court confirmed the 2014 ruling in O’Bannon which said that the cap the NCAA had in place from 1976 to 2015 was illegal. The 9th Circuit Court of Appeals ruled (and the Supreme Court chose not to overrule) that in the NCAA rule was “patently and inexplicably stricter than is necessary” and “an antitrust court can and should invalidate it and order it replaced.” In other words – the cap was illegal.

So the NCAA adopted a new, slightly more generous cap, which is why college athletes now get paid in cash as well as in-kind. That $2K - $6K I mentioned above? Yeah, you can thank the antitrust laws for that.

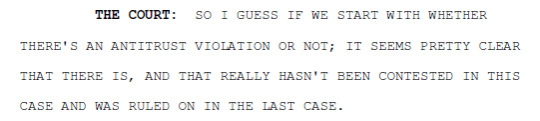

But the thing is, the court didn’t say that just because the cap was looser now that it was automatically ok. And so four years later, the new cap is back in court, awaiting a ruling from the same district court where O’Bannon was heard. In that case, we’re just waiting for the ruling but the judge (Judge Claudia Wilken) has already told us what she thinks:

What I think Judge Wilken meant was that it was clear that the current cap on compensation had an “anticompetitive effect” on thousands of athletes. What does that mean? It means there was lots of evidence that thousands of athletes had gotten less money under the current rule than they would have if there had been no rule (or a less restrictive rule).

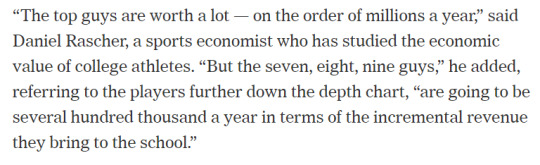

And one of the experts in that case, my friend and business partner, Dan Rascher testified to that exact effect. He explained his conclusions recently to the New York Times.

And this is what I think the real story is. Namely, that without the NBA/NBPA rule, which is legal, a dozen people or so would each earn millions of dollars more for one year. But without the NCAA rule, which is likely illegal, thousands of athletes would each earn tens or hundreds of thousands more – which is a far larger extraction of wealth – and the only parties responsible for that are the NCAA and its member institutions.

So when the hot-take crowd gets confronted with these sorts of facts, it’s fairly typical for them to fall back onto “ok, well, hot shot, you can complain all you want but no one has proposed a viable solution.” This is what I call the “what’s your plan” fallacy, namely that it’s not enough to point out where the real blame lies, it’s the requirement of the people who see the problem to also lay out, in full and glorious detail, how to fix it, or else the current rules get to stay in place forever. It’s something like the economic version of that tourist t-shirt, “the economic exploitation will continue until someone outside the system invents the perfect solution.”

But the “what's the plan” framing – where we have to agree on a fix before we can even entertain the possibility of ending a bad system – is bogus. You don’t keep letting a company pollute a river just because you haven’t figured out where they can properly send the pollution. You tell them to stop polluting and let them figure out what to do.

But even though it’s not the responsibility of the people who point out the problem to propose a solution, the secondary hot-take that “no one has offered a solution” is also just plain wrong. I myself have laid out at least three plans that would all fix the problem.

Eliminate the NCAA cap and let each conference set its own cap in competition with one another. This is the requested relief in the current case in front of Judge Wilken and was first proposed by me and Daniel Rascher (the professor quoted by the New York Times above) in 2000.

This would allow each conference to decide how much they think makes sense to offer in pay but require them to put that offer into a market where other conferences could pay more, and let the market decide, for each athlete, what a fair exchange of benefits for services is. It’s basically, you know, the way all markets work except it treats the conference as the unit of decision making rather than each school (and rather than allowing the NCAA to create a cartel[2] of all conferences, like they do now).

You can do a half-measure and end the cap on third-party payments to athletes. This is an inferior solution, because it opens up half the market – the market for athletes name, image, and likeness rights, but it leaves in place the cap on the other half of the market, the market for athletic services. In the long run, athletes will do about as well, but as appealing as this solution is – sometimes it’s called the Olympic model because it’s how Olympians are primarily (though not entirely) paid for their participation in the Olympics – it has problems. The biggest is that if compensation moves outside of the university environment, it is more likely to skirt Title IX.

That is, if athletes were paid for their services by schools or conferences, as in Plan 1 above, it’s very likely that the pay would be subject to Title IX matching. Roughly speaking, this would cut the market rate for male athletes in half and push up funding for female athletes accordingly. But if it’s Nike hiring Zion Williamson to do a shoe deal, it is much less likely there would be any need for a Title IX match. If you think Title IX is good, you should prefer Plan 1 to Plan 2, but either way, you’ll get to a market outcome that is less exploitative than the current system and works more efficiently to boot.

At least two States are adopting this approach now, Washington and California. You can read about these efforts here:

CA:https://theathletic.com/800397/2019/02/04/thompson-new-law-seeks-to-allow-california-collegiate-athletes-to-get-paid-for-use-of-their-name-image-and-likeness/

WA:http://www.spokesman.com/stories/2019/feb/21/outside-pay-for-college-athletes-gets-committee-ok/

There can be competitive entry by a rival college basketball league that considers “Amateurism” to be a problem that needs solving rather than a positive element of the sport. This is why I am proud to be a part of the executive team of the Historical Basketball League, the HBL. Because Amateurism is a Con.

I can already hear some of you asking:

WHAT IS THE HBL?

In June 2020, the HBL will launch in 12 cities across America and will work with the HBL Foundation to provide full scholarships to the cream of the crop – the top 150 or so college basketball players – to play for the HBL. In addition to those scholarships, which cannot be cancelled for injury or even if the athlete leaves for the NBA, the HBL will also pay athletes $50,000 to $150,000 and allow athletes to fully commercialize their name, image, and likeness. In other words, if the courts and society can’t force the NCAA to adopt Plan 1 or 2, the HBL is going to do it for them, buy up all the best talent, and show the world that labor markets aren’t exactly rocket science – the league that pays the best is going to get the best talent and they get the best ratings and then get the most revenue.

Now, to be clear, there is a lot more that is cool about the HBL. We are thrilled that fifteen-year NBA veteran David West has taken over our basketball operations, and Ricky Volante, Keith Sparks, and I are eager to work with David to make the league a success. Please check us out at HBLeague.com.

We’ll be playing our games in the summer to minimize the conflict between school and sports. Our athletes will be true students from Labor Day to Memorial Day, and then professional college athletes during the summer. We’ll focus on appropriate high-performance training, professional nutrition, and proper strength and conditioning. We’ll play by NBA rules and teach NBA schemes. We’ll be working to provide our athletes and their parents with financial literacy courses, public relations training, business courses, etc. We will holistically develop the whole person and send our athletes to the NBA and to other professional leagues across the globe – far better prepared for life on and off the court, and far better prepared than anything the NCAA provides today.

And no, the HBL is not going to ask the NCAA for permission to compete against them, or to agree on the optimal salary. The biggest fallacy of the “what’s your plan” hot take is that it assumes we need a plan at all. It implies athletes can't be subject to the same rules as everyone else. They can. By entering the same market as the NCAA – the college basketball market – what the HBL is saying is let’s just let the market do its thing.

In some sense, that's the common thread for all of the solutions, which is to recognize that we don’t have a plan for how we pay athletic directors, and no one worries why not. Just treat athletes like all other humans. It will all work out fine.

[1] Ok, to be technical it’s actually a monopsonist, which is just a fancy way of saying a monopolist when the monopolist is making the payments – like when it buys supplies or pays workers -- rather than charging the money. But that’s not important, I just want to make it clear I know the difference

[2] An economic cartel is not a drug cartel. To be an economic cartel you just have to get together with your potential competitors and agree not to compete on price. For example, you could get all 350+ D1 schools to agree on how much to pay athletes for their services, and this would make you a cartel. I’m looking at you, NCAA.

5 notes

·

View notes