#royal picture gallery mauritshuis

Photo

Adriaen Hanneman (Dutch, 1603-1671)

Portrait of Maria Henriette Stuart, Prince Willem II of Oranje with a Negro Page, c.1664

Mauritshuis Royal Picture Gallery

#art#dutch art#dutch#european art#western civilization#maria hentiette stuart#classical art#royal#noble#nobility#fine art#fine arts#oil painting#europe#europa#orientalism#posthumous#traditional art

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Artista: Jan Brueghel el Viejo (Bruselas 1568 - 1625 Amberes) y Peter Paul Rubens (Siegen 1577 - 1640 Amberes)

Título: El Jardín del Edén con la Caída del Hombre

Datación: 1615

Número de inventario: 253

Técnica: aceite

Material: panel

Dimensiones: 74,3 x 114,7 centímetros

Inscripciones:

Firmado, abajo a la izquierda: PETRI PAVLI RVBENS FIGR

Firmado, Abajo a la derecha: IBRUEGHEL FEC

IB en ligadura

Procedencia: Pieter de la Court van der Voort y herederos, Leiden, en o antes de 1710-1766; Príncipe Guillermo V, La Haya, 1766-1795; confiscado por los franceses, transferido al Muséum Central des Arts/Musée Napoléon (Musée du Louvre), París, 1795-1815; Royal Picture Gallery, alojada en la Galería Príncipe Guillermo V, La Haya, 1816; transferida al Mauritshuis, 1822

Este cuadro es obra de dos famosos maestros flamencos: Rubens y Brueghel. Realizaron varias versiones de este tipo de cuadros, que pretendían ser piezas de exhibición que combinaran lo mejor de ambos artistas.

Aunque Brueghel fue el responsable de la composición, Rubens comenzó el cuadro. De forma muy esquemática, con pintura fina, pintó a Adán y Eva, el árbol, el caballo y la serpiente. Después, Brueghel se ocupó de las plantas y los animales, que pintó con una precisión enciclopédica en el acabado de la pintura.

Información e imagen de la web del Mauritshuis, The Hague.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Skulls in Art (’Halloween in Art’ Series)

Top LTR:

L:

'Skull of a Skeleton with Burning Cigarette (Kop van een skelet met brandende sigaret), (1885–86),

Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890),

Oil on canvas, H 32 cm × W 24.5 cm,

Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, Netherlands (1973–).

R:

'Pyramid of Skulls,' (1901),

Paul Cézanne (1839–1906),

Oil on canvas, H 37 cm × W 45.5 cm,

Private Collection.

Bottom LTR:

L:

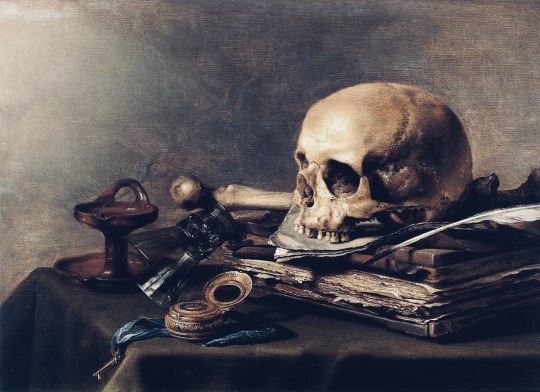

'Vanitas Still Life,' (1630),

Pieter Claesz (1597–1660),

Oil on panel, H 39.5 cm x W 56 cm,

Royal Picture Gallery Mauritshuis, The Hague, Netherlands (1960–).

R:

'Skull,' (1887),

Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890),

Oil on canvas, H 42.4 cm x W 30.4 cm,

Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, Netherlands (Vincent van Gogh Foundation) (1994–).

#art#photoset#skulls#skull#skulls in art#skeletons#skeletons in art#halloween in art#halloween#skull of a skeleton with burning cigarette#kop van een skelet met brandende sigaret#vincent van gogh#van gogh#van gogh museum#dutch art#pyramid of skulls#paul cézanne#oil painting#painting#vanitas paintings#pieter claesz#royal picture gallery mauritshuis#post impressionism#pointillism#neo impressionism#cubism#modern art#still life#vincent van gogh foundation#french art

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Master of Frankfurt, St Catherine, St Barbara, 1510–1520, oil on panel 158.7 x 70.8 cm (each), The Royal Picture Gallery Mauritshuis, The Hague

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Johannes Vermeer - The Girl with a Pearl Earring (detail), Royal Picture Gallery Mauritshuis - The Hague Netherlands

#art #painting #vermeer

0 notes

Text

Top 10 Places to Visit in the Netherlands

Top 10 Places to Visit in the Netherlands

Famously known for its breathtaking scenery and quaint but charming windmills, the Netherlands is second to none as one of the most gorgeous and pristine countries to visit in Europe. Today, Book My Bharat is taken the serendipitous task of jotting down the top 10 places to visit in the Netherlands.

Nestled in the beautiful landscape of Northwestern Europe, the Netherlands is known for its vibrant cities, picturesque landscapes, and rich cultural heritage. Exploring the Netherlands offers a delightful mix of history, art, and natural beauty that is sure to captivate every traveler.

Immerse yourself in the art of famous Dutch masters such as Rembrandt and Van Gogh at world-class museums, stroll through charming tulip fields in spring, or take a bike ride through quaint villages and tulip-dotted countryside. So grab your camera, put on your walking shoes, and get ready to embark on a remarkable journey as we explore the wonders of the Netherlands.

Top 10 Places to Explore in the Netherlands

Every corner and crevice of our country exudes a captivating charm reminiscent of the captivating chapters of an enthralling tale. Countless places boast awe-inspiring panoramas, but only a select few attain the prestigious status of captivating the entire globe. Therefore, when you find yourself in this town, make certain to embark on a journey through this exceptional destination –

Rotterdam

Rotterdam, once a humble 13th-century fishing village, now stands as the Netherlands’ most contemporary city. Similar to Amsterdam, it embraces a bike-friendly culture and offers numerous districts for exploration. Among these, the renowned Delfshaven district holds historical significance as the departure point for the pilgrims’ voyage in 1620. Notably, the Erasmus Bridge captivates with its distinctive and commanding presence, earning acclaim as a remarkable artistic masterpiece, gracefully spanning Europe’s largest harbor. The highlight for most visitors, however, lies at the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen. This renowned institution exhibits a vast collection of artworks ranging from the Middle Ages to modern times, including revered masterpieces by Dali, Van Gogh, Bosch, and Rembrandt.

Amsterdam

Amsterdam, a beloved tourist destination in Europe, is renowned for its vibrant party scene, cannabis culture, and famous red light district. However, this capital city of the Netherlands offers much more to travelers. Enchanting with its picturesque canal ring, historical structures, world-class museums, and iconic landmarks like the Anne Frank House, Vondelpark, and the floating flower market called Bloemenmarkt. Situated in North Holland, this city is a sprawling metropolis divided into several districts, easily navigable through public buses, trams, metro lines, and bicycles. Here, tourists revel in canal cruises, sightseeing, exploration of renowned art museums like the Van Gogh Museum and Rijksmuseum, and attend performances at esteemed concert halls like the Concertgebouw.

The Hague

The Hague is a captivating destination renowned for its contemporary art exhibits at the Gemeentemuseum Den Haag and the Royal Picture Gallery Mauritshuis. Also known as the Royal City by the Sea, this city holds a special allure with its association with Dutch Royalty and the inviting North Sea town of Scheveningen, a popular spot for summer relaxation. This hot spot offers a delightful experience for visitors. Notably, it houses the Binnenhof, the Dutch government’s seat, despite Amsterdam being the capital. Other attractions include Madurodam, a miniature city, and the panoramic view of the Scheveningen Sea in the 19th-century masterpiece, Panorama Mesdag.

Utrecht

Utrecht’s canals narrate a tale of dual levels, with ancient wharf cellars transformed into exceptional waterfront dining and drinking destinations. This distinctive feature distinguishes the city. Pedaling t hrough Utrecht’s bike-friendly streets allows exploration of its majestic churches and charming cafes. For history enthusiasts, Utrecht proves to be a treasure trove, boasting architectural marvels like the Dom Tower and insightful museums such as the Centraal Museum. Immerse yourself in the past while relishing the present in this enchanting city—a haven for both culinary delights and cultural enlightenment. With Utrecht, there’s a story waiting to be discovered around every canal bend.

Delft

Delft, a progressive town with a restored antiquated charm, offers a delightful escape from bustling Amsterdam. Its Renaissance-style City Hall on Market Square and picturesque Holland canals define the city’s unique architectural beauty. Perfect for a day trip or a longer vacation, this town boasts attractions like The Prinsenhof, where bullet holes from William of Orange’s assassination still bear witness. This museum not only recounts the story of the Eighty Years’ War but also showcases captivating artworks. For those seeking a Johannes Vermeer memento, a visit to the Vermeer Centrum in Delft is a must, offering souvenirs and prints celebrating the famous artist.

Leiden

The picturesque city of Leiden is a great place to visit for its scenic, tree-lined canals that are marked with old windmills, wooden bridges, and lush parks. A boat ride down one of these lovely canals makes for an unforgettable experience. Attractions in this city include the numerous museums that range from science and natural history to museums dedicated to windmills and Egyptian antiquities. The Hortus Botanicus offers sprawling botanical gardens and the world’s oldest academic observatory. Visitors can also admire the beautiful architecture of the 16th-century Church of St. Peter and check out its association with several historic people, including the American pilgrims.

Maastricht

Maastricht, located in southern Holland, is renowned for its vibrant city square, the Vrijthof, which attracts visitors with its lively ambiance. The square is surrounded by notable landmarks such as the impressive Saint Servatius Church, Saint Jan’s Cathedral, and the vast Vestigingswerkens fortifications. Throughout the year, the Vrijthof hosts numerous festivals, particularly during the autumn and winter seasons, delighting locals and tourists alike. Additionally, this bustling town square offers a plethora of delightful cafes, trendy bars, captivating galleries, and intriguing shops. Other must-see attractions in Maastricht include the St. Pietersberg Caves and the Helpoort, the Netherlands‘ oldest surviving town gate of its kind.

Haarlem

Haarlem, the heart of the tulip bulb-growing district, is affectionately known as Bloemenstad, or ‘flower city,’ and proudly hosts the Annual Bloemencorso Parade. Nestled by the serene Spaarne River, this peaceful community showcases its medieval charm with well-preserved historic buildings. The Grote Markt city center invites visitors to indulge in shopping and admire the breathtaking architecture, while museums add to the city’s allure. Among them is the esteemed Teylers Museum, the country’s oldest, offering captivating displays of natural history, art, and science. Art enthusiasts flock to the Franz Hals Museum, home to magnificent works by Dutch masters. Haarlem is a haven for culture, nature, and unforgettable experiences.

Groningen

This city is the epitome of cultural diversity and boasts two highly revered colleges, which makes this city one of the most boujee places to visit in the northern Netherlands, especially if the root cause of your visit is art, business, and attending concerts. The vibrant city also offers a lively music and theatre scene, with numerous street cafes hosting captivating live performances. Renowned for its thriving student community, Groningen boasts a vibrant nightlife that attracts people from far and wide. The Grote Markt, the Peperstraat, and the Vismarkt are among the top spots where nightlife comes alive, offering a plethora of entertainment options to cater to diverse tastes.

Gouda

Gouda is a city that encourages exploration, whether it’s wandering along its canals, strolling through its charming streets, or immersing yourself in its vibrant cultural scene. The city is home to numerous museums, art galleries, and theatres that showcase the region’s rich artistic heritage. As you delve deeper into Gouda’s history, you’ll discover fascinating stories and traditions that have shaped the city over the centuries. From its origins as a medieval market town to its role in the Dutch Golden Age, Gouda has a captivating past that can be experienced through its museums and historic sites, such as the Gouda Museum and the De Waag.

0 notes

Photo

“Henry VIII was at Whitehall Palace when the Tower guns signaled that he was once more a free man. He then appeared dressed in white mourning as a token of respect for his late queen, called for his barge, and had himself rowed at full speed to the Strand, where Jane Seymour had also heard the guns. News of Anne Boleyn’s death had been formally conveyed to her by Sir Francis Bryan; it does not seem to have unduly concerned her, for she spent the greater part of the day preparing her wedding clothes, and perhaps reflecting upon the ease with which she had attained her ambition: Anne Boleyn had had to wait seven years for her crown; Jane had waited barely seven months.

It was common knowledge that Henry would marry Jane as soon as possible; the Privy Council had already petitioned him to venture once more into the perilous seas of holy wedlock, and it was a plea of the utmost urgency due to the uncertainty surrounding the succession. Both the King’s daughters had been declared bastards, and his natural son Richmond was obviously dying. A speedy marriage was therefore not only desirable but necessary, and on the day Anne Boleyn died the King’s imminent betrothal to Jane Seymour was announced to a relieved Privy Council. This was news as gratifying to the imperialist party, who had vigorously promoted the match, as it would soon be to the people of England at large, who would welcome the prospect of the imperial alliance with its inevitable benefits to trade.

Although the future Queen had rarely been seen in public, stories of her virtuous behavior during the King’s courtship had been circulated and applauded. Chapuys, more cynical, perceived that such virtue had had an ulterior motive, and privately thought it unlikely that Jane had reached the age of twenty-five without having lost her virginity, ‘being an Englishwoman and having been so long’ at court where immorality was rife. However, he assumed that Jane’s likely lack of a maidenhead would not trouble the King very much, ‘since he may marry her on condition she is a maid, and when he wants a divorce there will be plenty of witnesses ready to testify that she was not’.

This apart, Chapuys and most other people considered Jane to be well endowed with all the qualities then thought becoming in a wife: meekness, docility and quiet dignity. Jane had been well groomed for her role by her family and supporters, and was in any case determined not to follow the example of her predecessor. She intended to use her influence to further the causes she held dear, as Anne Boleyn had, but, being of a less mercurial temperament, she would never use the same tactics.

Jane’s well-publicized sympathy for the late Queen Katherine and the Lady Mary showed her to be compassionate, and made her a popular figure with the common people and most of the courtiers. Overseas, she would be looked upon with favour because she was known to be an orthodox Catholic with no heretical tendencies whatsoever, one who favoured the old ways and who might use her influence to dissuade the King from continuing with his radical religious reforms.

Jane was of medium height, with a pale, nearly white, complexion. ‘Nobody thinks she has much beauty,’ commented Chapuys, and the French ambassador thought her too plain. Holbein’s portrait of Jane, painted in 1536 and now in the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, bears out these statements, and shows her to have been fair with a large, resolute face, small slanting eyes and a pinched mouth. She wears a sumptuously bejeweled and embroidered gown and head-dress, the latter in the whelk-shell fashion so favoured by her; Holbein himself designed the pendant on her breast, and the lace at her wrists. This portrait was probably by his first royal commission after being appointed the King’s Master Painter in September 1536; a preliminary sketch for it is in the Royal Collection at Windsor, and a studio copy is in the Mauritshuis in The Hague. Holbein executed one other portrait of Jane during her lifetime.

Throughout the winter of 1536-7, he was at work on a huge mural in the Presence Chamber in Whitehall mural no longer exists, having been destroyed when the palace burned down in the late seventeenth century. Fortuitously, Charles II had before then commissioned a Dutch artists, Remigius van Leemput, to make two small copies, now in the Royal Collection and at Petworth House. His style shows little of Holbein’s draughtsmanship, but his pictures at least give us a clear impression of what the original must have looked like. The figure of Jane is interesting in that we can see her long court train with her pet poodle resting on it. Her gown is of cloth of gold damask, lined with ermine, with six ropes of pearls slung across the bodice, and more pearls hanging in a girdle to the floor. Later portraits of Jane, such as those in long-gallery sets and the miniature by Nicholas Hilliard, all derive from this portrait of Holbein’s original likeness now in Vienna, yet they are mostly mechanical in quality and anatomically awkward.

However, it was not Jane’s face that had attracted the King so much as the fact that she was Anne Boleyn’s opposite in every way. Where Anne had been bold and fond of having her own way, Jane showed herself entirely subservient to Henry’s will; where Anne had, in the King’s view been a wanton, Jane had shown herself to be inviolably chaste. And where Anne had been ruthless, he believed Jane to be naturally compassionate. He would be in years to come remember her as the fairest, the most discreet, and the most meritorious of all his wives.

Her contemporaries thought she had a pleasing sprightliness about her. She was pious, but not ostentatiously so. Reginald Pole, soon to be made a cardinal, described her as ‘full of goodness’, although Martin Luther, hearing of her reactionary religious views, feared her as ‘an enemy of the Gospel’. According to Chapuys, she was not clever or witty, but ‘of good understanding’. As queen, she made a point of distancing herself from her inferiors, and could be remote and arrogant, being a stickler for the observance of etiquette at her court. Chapuys feared that, once Jane had had a taste of queenship, she would forget her good intentions towards the Lady Mary, but his fears proved unfounded. Jane remained loyal to her supporters, and to Mary’s cause, and in the months to come would endeavor to heal the rift between the King and his daughter.

- Alison Weir, The Six Wives of Henry VIII

“A story of a later date had Queen Anne finding Mistress Seymour actually sitting on her husband’s lap; ‘betwitting’ the King, Queen Anne blamed her miscarriage upon this unpleasant discovery. There was said to have been ‘much scratching and bye-blows between the queen and her maid’.

Unlike the King’s invocations of the divine will, however, there is no contemporary evidence for such robust incidents; the character of Jane Seymour that emerges in 1536 is on the contrary chaste, verging on the prudish. As we shall see, there is good reason to believe that the King found in this very chastity a source of attraction; as he had once turned to the enchantress Anne Boleyn from the virtuous Catherine. Yet before turning to Jane Seymour’s personal qualities for better or for worse, it is necessary to consider the family from which she came …

The Seymours were a family of respectable and even ancient antecedents in an age when, as has already been stressed, such things were important. Their Norman ancestry – the name was originally St Maur – was somewhat shadowy although a Seigneur Wido de Saint Maur was said to have come over to England with the Conquest. More immediately, from Monmouthshire and Penbow Castle, the Seymours transferred to the west of England in the mid-fourteenth century with the marriage of Sir Roger Seymour to Cecily eventual sole heiress of Lord Beauchamp of Hache. Other key marriages brought the family prosperity. Wolf Hall in Wiltshire, for example (scene of Henry’s autum idyll with Jane if legend is to be believed) came with the marriage of a Seymour to Matilda Esturmy, daughter of the Speaker of Commons, in 1405. Another profitable union, bringing with it mercantile links similar to those of the Boleyns, was that of Isabel, daughter and heiress of Mark William Mayor of Bristol, to a Seymour in 1424.

Sir John Seymour, father of Jane, was born in about 1474 and had been knighted in the field by Henry VII at the battle of Blackheath which ended a rebellion of 1497. From this promising start, he went on to enjoy the royal favour throughout the next reign. Like Sir Thomas Boleyn, he accompanied Henry VIII on his French campaign of 1513, was present at the Field of Cloth of Gold, attended at Canterbury to meet Charles V; by 1532 he had become a Gentleman of the Bedchamber. Locally, again echoing the career of Thomas Boleyn, he had acted as Sheriff of both Wiltshire and Dorset. It was a career that lacked startling distinction – here was no Charles Brandon ending up a duke – but one which brought him close to the monarch throughout his adult life.

Sir John’s reputation was that of a ‘gentle, courteous man’. That again was pleasant but not startling. But there was something outstanding about him, or at least about his immediate family. Sir John himself came of a family of eight children; then his own wife gave birth to ten children – six sons and four daughters. All this was auspicious for his daughter, including the number of males conceived at a time when women’s ‘aptness to procreate children’ in Wolsey’s phrase about Anne Boleyn, was often judged by their family record.

It was however from her mother, Margery Wentworth – once again echoing the pattern of Anne Boleyn – that Jane Seymour derived that qualifying dash of royal blood so important to a woman viewed as possible breeding stock. Margery Wentworth was descended from Edward III, via her great-great-grandmother Elizabeth Mortimer, Lady Hotspur. Indeed, in one sense – that of English royal blood – Jane Seymour was better born than Anne Boleyn, since she descended from Edward III, whereas Anne Boleyn’s more remote descent was from Edward I. This Mortimer connection meant that Jane and Henry VIII were fifth cousins. But of course neither the Wentworths nor the Seymours were as grand as Anne Boleyn’s maternal family, the ducal Howards.

The Seymours may not have been particularly grand, but close connections to the court had made them, by the generation of Jane herself, astute and worldly wise. Sir John Seymour was over sixty at the inception of the King’s romance with his daughter (and would in fact die before the end of the year 1536); even before that the dominant male figure in Jane’s life seems to have been her eldest surviving brother Edward, described by one observer about this time as both ‘young and wise’. Being young, he was ambitious, and being wise, able to keep his own counsel in pursuit of his plans. Contemporaries found him slightly aloof – he lacked the easy charm of his younger brother Thomas p but they did not doubt his intelligence. Edward Seymour was cultivated as well as clever; he was a humanist and also, as it turned out, genuinely interested in the tenets of the reformed religion (unlike his sister Jane) … The vast family of Sir John Seymour began with four boys: John (who died), Edward, Henry and Thomas, born in about 1508. A few years later the King would speak ‘merrily’ of handsome Tom’s proverbial virility. He was confident that a man armed with ‘such lust and youth’ would be able to please a bride ‘well at all points’. Then came Jane, probably born in 1509, the fifth child but the eldest girl. After that followed Elizabeth, Dorothy and Margery; two sons who died in the sweating sickness epidemic of 1528 made up the ten.

Apart from her presumed fertility, what else did Jane Seymour, now in her mid-twenties (the age incidentally at which Anne Boleyn had attracted the King’s attention), have to offer? Polydore Vergil gave the official flattering view when he described her as ‘a woman of the utmost charm both in appearance and character’, and the King’s best friend Sir John Russell called her ‘the fairest of all his wives’ – but this again was likely to loyalty to Jane Seymour’s dynastic significance. From other sources, it seems likely that the charm of her character considerably outweighed the charm of her appearance: Chapuys for example described her as ‘of middle stature and no great beauty’. Her most distinctive aspect was her famously ‘pure white’ complexion. Holbein gives her a long nose, and firm mouth, with the lips slightly compressed, although her face has a pleasing oval shape with the high forehead then admired (enhanced sometimes by discreet plucking of the hairline) and set off by the headdress of the time. Altogether, if Anne Boleyn conveys the fascination of the new, there is a dignified but slightly stolid look to Jane Seymour, appropriately reminiscent of English medieval consorts.

But the predominant impression given by her portrait – at the hands of a master of artistic realism – is of a woman of calm and good sense. And contemporaries all commented on Jane Seymour’s intelligence: in this she was clearly more like her cautious brother Edward than her dashing brother Tom. She was also naturally sweet-natured (no angry words or tantrums here) and virtuous – her virtue was another topic on which there was general agreement.

... Her survival as a lady-in-waiting to two Queens at the Tudor court still with a spotless reputation may indeed be seen as a testament to both Jane Seymour’s salient characteristics – virtue and common good sense . A Bessie Blount or Madge Shelton might fool around, Anne Boleyn might listen or even accede to the seductive wooings of Lord Percy: but Jane Seymour was unquestionably virginal.

In short, Jane Seymour was exactly the kind of female praised by the contemporary handbooks to correct conduct; just as Anne Boleyn had been the sort they warned against. There was certainly no threatening sexuality about her. Nor is it necessary to believe that her ‘virtue’ was in some way hypocritically assumed, in order to intrigue the King (romantic advocates of Anne Boleyn have sometimes taken this line). On the contrary, Jane Seymour was simply fulfilling the expectations for a female of her time and class: it was Anne Boleyn who was – or rather who had been – the fascinating outsider.

- Antonia Fraser, The Wives of Henry VIII

“Whilst Jane was always denied a political role, her political interests are clear. She favoured Mary, attempted to save the monasteries and sympathized with the rebels during the Pilgrimages of Grace. Jane’s politics were largely conservative. Her strong character is visible both by her ruthlessness in watching the fall of Anne Boleyn and in the way in which she ruled her household. Jane could have been a queen as strong and influential as Catherine of Aragon or Anne Boleyn had been in the early years of their marriages. Unfortunately for Jane, when the opportunity finally arose with the birth of her son, she did not survive. Had Jane lived, as the mother of the king’s heir, she could have asserted her authority safe in the knowledge that her position was finally secure. After Henry’s death, when Jane’s son was only nine years old, she would have had a very strong claim to the regency as the mother of the king. Jane Seymour could have been so much more and, whilst it is possible to glimpse her potential, much of what she could have achieved will forever be speculation.

Jane did not live to take on the political role that would have been open to her as the mother of the heir to the throne and her real legacy is her son, Edward VI, and the prominence of her brothers, Edward and Thomas Seymour. Although Henry would go on to have another three wives after Jane’s death, Edward was his only son and, on Henry’s death in January 1547, he became king aged nine as Edward VI Edward was hailed by many in England as a future great king and Jane would have been proud of her son. Edward’s tutor, Sir John Cheke, for example, wrote of the king that ‘I prophesy indeed, that, with the lord’s blessing, he will prove such a king, as neither to yield to Josiah in the maintenance of the true religion, nor to Solomon in the management of the state, nor to David in the encouragement of godliness’. Roger Ascham, the tutor of Edward’s sister, Elizabeth, also sang the youth king’s praises, writing that ‘he is wonderfully advanced of his years’. Edward was raised to be a king and received a formidable education, writing very advanced letters even in early childhood (even if is clear that he must have received some assistance in the earlier letters). In one letter to his father, Edward wrote:

In the same manner as, most bounteous king, at the dawn of day, we acknowledge the return of the sun to our world, although by the intervention of obscure clouds, we cannot behold manifestly with our eyes that resplendent orb; in like manner your majesty’s extraordinary and almost incredible goodness so shines and beams forth, that although present I cannot behold it, though before me, with my outward eyes, yet never can it escape from my heart.

Edward was raised to be king in the manner of his father but in his appearance, with his pale skin and fair hair, he always resembled Jane.

Jane’s greatest regret, when she came to realize that she was dying, was that she would not live to see her son grow up …

Jane’s legacy is also her own reputation and her relationship with Henry VIII. Jane never inspired the deep obsession in the king that he felt for Anne Boleyn or the admiring love that he, at first, felt for Catherine of Aragon. Instead, he married her almost on a whim. She was the woman best placed at the perfect time. There is even some evidence that Henry came to regret his haste in marrying Jane after seeing some other beautiful ladies at his court. Jane never raised the passion in Henry that some of his other wives did. Throughout their marriage, it is clear that Henry did not entirely view his marriage to Jane as permanent. It was essential that Jane fulfilled her side of the bargain and that was to bear a son. Until that time, as Jane was very well aware, she was entirely dispensable.

In spite of this, with her death in giving him the son he craved, Henry’s feelings towards Jane entirely changed and he came to look back on their marriage through rose-tinted spectacles. A commemoration to Jane was written some time after her death and perhaps best sums up how Henry came to view her:

Among the rest whose worthie lyves

Hath runne in vertue’s race,

O noble Fame! Persue thy trayne,

And give Queene Jane a place.

A nymphe of chaste Dianae’s trayne,

A virtuous virgin eke; In tender youth a matron’s harte,

With modest mynde most meeke.

Jane spent her entire marriage trying to prove to Henry that she was his ideal woman and, posthumously, she succeeded.

- Elizabeth Norton, Jane Seymour: Henry VIII’s True Love

“How a woman like Jane Seymour became Queen of England is a mystery. In Tudor terms she came from nowhere and was nothing.

Chapuys confronted the riddle in his dispatch of 18 May 1536, which was addressed to Antoine Perrenot, the Emperor’s minister, rather than to the Emperor Charles V himself. Freed from the decorum of writing to his sovereign, the ambassador expressed himself bluntly. ‘She is the sister’, he began, ‘of a certain Edward Seymour, who has been in the service of his Majesty [Charles V]’; while ‘she [herself] was formerly in the service of the good Queen [Catherine]’.

As for her appearance , it was literally colourless. ‘She is of middle height, and nobody thinks she has much beauty. Her complexion is so whitish that she may be called rather pale.’

This is a neat pen-portrait of the woman whose mousy, peaked features and mean, pointed chin, are denred by Holbein with his characteristic, unsparing honesty.

So much Chapuys could see.

But when he turned to her supposed moral character he gave his prejudices full rein. ‘You may imagine’, he wrote Perrenot, man-to-man, ‘whether, being an Englishwoman, and having been so long at Court, she would not hold it a sin to be virgo intacta.’ ‘She is not a woman of great wit,’ he continued. ‘But she may have’ -and here he became frankly coarse- ‘a fine enigme.’

‘Enigme’ means ‘riddle’ or ‘secret’, as in ‘secret place’ or the female genitalia. ‘It is said’, he concluded, ‘that she is rather proud and haughty.’ ‘She seems to bear great goodwill and respect to [Mary]. I am not sure whether later on the honours heaped on her will to make her change her mind.’

Whatever was there here -a woman of no family, no beauty, no talent and perhaps not much reputation (though there is no need to accept all of Chapuys’s slanders)- to attract a man who had already been married to two such extraordinary women as Catherine and Anne?

But maybe Jane’s very ordubarubess was tge oiubt, Anne had been exciting as a mistress. But she was too demanding, too mercurial and tempestuous, to make a good wife. Like the Gospel which she patronised, she seemed to have come ‘not to send peace but the sword’ and to make ‘a man’s foes ... them of his own household’ (Matthew 10.34-6).

Henry was weary of scenes and squabbles, weary too of ruptures with his nearest and dearest and his oldest and closest friends. He wanted his family and friends back. He wanted domestic peace and the quiet life. He also, more disturbingly, wanted submission. For increasing age and the Supremacy’s relentless elevation of the monarchy had made him ever more impatient of contradiction and disagreement. Only obedience, prompt, absolute and unconditional, would do.

And he could have none of this with Anne.

Jane, on the other hand, was everything that Anne was not. She was calm, quiet, soft-spoken (when she spoke at all) and profoundly submissive, at least to Henry ...”

- David Starkey, Six Wives: The Queens of Henry VIII

Images: Jane Seymour painted by Hans Holbein the Younger. Variousa actresses from costume dramas that have played Henry VIII’s third consort. Elly Condron from the documentary drama Secrets of the Six Wives documentary presented by Lucy Worsley. Anne Stallybras from the BBC miniseries The Six Wives of Henry VIII (1970). Jane Asher from the BBC film Henry VIII & his Six Wives (1972). Lastly, Kate Phillips from Wolf Hall (2014).

#Jane Seymour#Tudor History#dailytudors#historians assesment of Jane Seymour#David Starkey#Alison Weir#Antonia Fraser#Elizabeth Norton

67 notes

·

View notes

Text

Antoon François Heijligers

Interior of the Rembrandt Room in the Mauritshuis in 1884

After Johan Maurits’s death in 1679, the Mauritshuis had several functions before it became a museum in 1822. The collection itself came from King Willem I (1772-1843), hence the museum’s official name: the Royal Picture Gallery Mauritshuis.

The king had a significant influence on the museum’s acquisition policy. He decreed, for example, that Rembrandt’s Anatomy Lesson should hang here. He also purchased Jan de Baen’s portrait of Johan Maurits, thereby bringing the master of the house back home.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Museum Mauritshuis, the Hague; 2016

In 2009 Hans van Heeswijk Architects was commissioned to connect the Royal Picture Gallery Mauritshuis to the building across the street, at Plein 26, via an underground foyer. The addition of the new wing at Plein 26 actually doubles the size of the museum.

The Masterplan included the renovation of the existing Mauritshuis. The underground foyer is located six meters below street level, but as daylight penetrates from all sides, it feels very light and spacious. Access to the foyer is provided by the unique self-supporting glass lift (9 meters high) or staircase leading down from the forecourt. The cage of the lift is guided along structural glass fins. The new exhibition space, lecture theatre, education suite and library, the current museological and visitor facilities such as entrance, brasserie, shop, cloakroom are enlarged and brought in line with the 21st-century requirements.

The Mauritshuis houses a world-famous collection of art. The heart of the collection consists of paintings from the Dutch Golden Age, including absolute highlights such as Vermeer’s ‘Girl with a Pearl Earring’, Rembrandt’s ‘The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp’ and Carel Fabritius’ ‘The Goldfinch’.

#Architecture#royal picture gallery mauritshus#mauritshuis#the hague#extensions#art#art museum#rembrant van rijn#vermeer#fond of architecture

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Adriaen Hanneman (Dutch, 1603-1671)

Portrait of Maria Henriette Stuart, Prince Willem II of Oranje with a Negro Page, c.1664

Mauritshuis Royal Picture Gallery

#art#fine art#traditional art#Adriaen Hanneman#dutch#dutch art#1600s#classical art#Maria Henriette Stuart#oil painting#women in art#fine arts#european art#western civilization#europe#europa#female portrait#female#portrait#orientalism

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

Anatomy Lesson of Dr Nicolaes Tulp (1632) by Rembrandt

Mauritshuis Royal Picture Gallery

"Because we humans are big and clever enough to produce and utilize antibiotics and disinfectants, it is easy to convince ourselves that we have banished bacteria to the fringes of existence. Don’t you believe it. Bacteria may not build cities or have interesting social lives, but they will be here when the Sun explodes. This is their planet, and we are on it only because they allow us to be.

Bacteria, never forget, got along for billions of years without us. We couldn’t survive a day without them. --"

A Short History of Nearly Everything. Bill Bryson. 2003

1 note

·

View note

Text

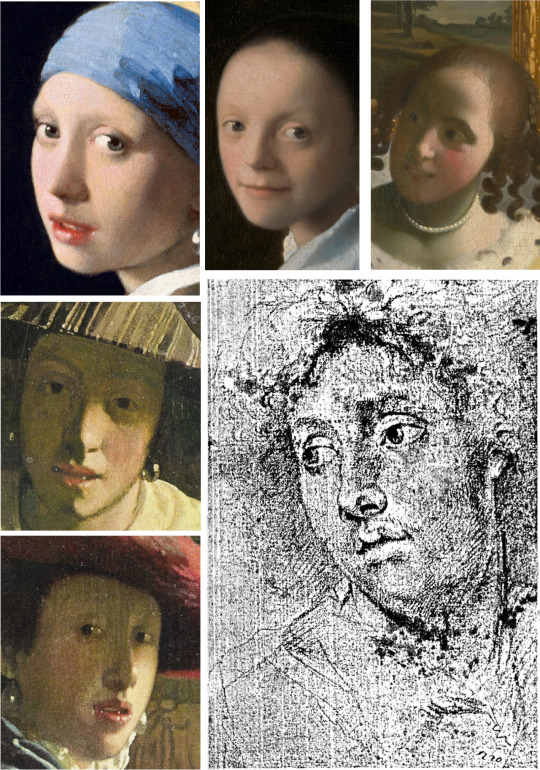

Vermeer

Inside my copy of Ludwig Goldsheider's Phaidon Press Vermeer I wrote my name and the date of purchase, 1958. I was then fourteen years old. The battered volume is a record, therefore, of an attraction to this artist that stretches back to childhood. Not unnaturally I would like to find a way to acknowledge all that he has meant to me over the intervening years. I have no gift to write of his art like Lawrence Gowing - still less like Proust - but in any case my preference is to use connoisseurship to extend, if possible, our understanding of his oeuvre by seeing if there are viable addenda that can be appended to it; and that is the main purpose of this Study. A secondary aim is to draw attention to the dangers involved in 'cleaning' what we already have. By way of caveat I urge any readers I may have not to expect everything adduced to look like their idea of 'a Vermeer'. Connoisseurship has to allow for development. An early Cézanne does not look much like a late one.

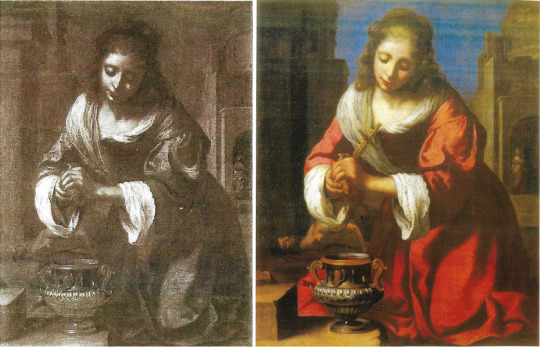

To begin at the beginning of Vermeer's career as a painter is chronologically proper but somewhat frustrating because we know that he is farthest from where he needs to be and where we wish him to be. Through his and his father's picture-dealing he comes into contact with Italian paintings of a religious and mythological nature which encourage him to try his hand in a similar vein. What survives of this derivative, experimental period is the St Praxedis - his version of a composition by a Florentine artist Felice Ficherelli - and the Diana and her Companions.

St Praxedis by Ficherelli (left) and Vermeer’s copy (right)

Being by Vermeer, these are not bad pictures; indeed the St Praxedis is that rare thing, a copy better than its original. In both works there is a fluency of brushwork, a Baroque rhythm, and a palette that at this stage includes a yellow, a deep blue, a winey brown, and a rose red that, mixed with white, becomes a violet.

I can only suggest one work to add to this early phase of Vermeer's oeuvre and that is a picture of the head and shoulders of a rosy-cheeked girl.

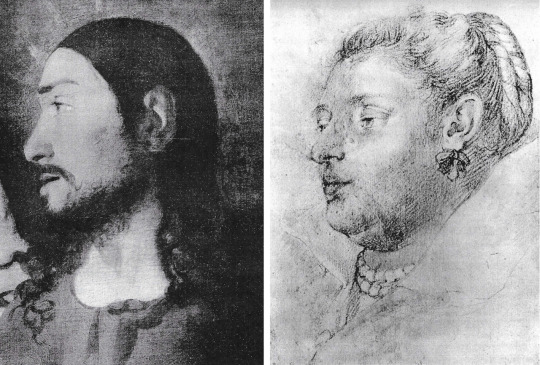

Portrait of a Girl by De Bray (left) and detail of St Praxedis (right)

When it passed through the hands of a London dealer (Chaucer Fine Arts) in 1989 it was attributed, not very accurately, to Jan de Bray. The face is painted in a style hard to reconcile with any of the young female faces in later Vermeer, but it does seem close to that of St Praxedis and to the facial types in the Diana picture. Common to all of them are the rose-white-violet juxtaposition, the swirling drapery and soft sfumato.

Christ at the House of Mary and Martha (National Gallery Scotland)

With the large ‘Christ in the house of Mary and Martha’ at Edinburgh we may be moving backwards rather than forwards chronologically, but Vermeer seems recognizably more Vermeerish. He is still in his broad-brush Religion and Myth phase but the religion is as domesticated as it can be in that story of Mary and Martha, so one feels that he is moving towards the territory that he will make his own. Even in the earliest pictures it is noticeable how women predominate as we know that they will in the future. On the relative merits of Mary’s life and Martha’s, Vermeer's art is, and remains, tacitly neutral: it pays tribute to both. As if to illustrate this there is a study in watercolour for the figure of Mary, and a drawing that is not for the figure of Martha (being stylistically later) but certainly alludes to her servant role.

In the Printroom at Leipzig is a remarkable wash drawing which Bernhard Degenhart included in an anthology of European drawings (Europaisches Handzeichnungen) published at Dresden in 1943 as the work of the landscapist Jan Siberechts.

Drawing attributed to Siberechts (Leipzig) and detail of Martha

That attribution can be dismissed because there is nothing in Siberechts to support it beyond the flimsy fact of there being a landscape drawing on the verso. The little pen sketches of figures at the top and lower right of the sheet are by another artist; disregarding those, I think that there is a strong possibility that what we have here is a study by Vermeer for the figure of Mary in the Edinburgh picture; there the listening head is swivelled a little further round towards Christ. The light in consequence falls differently, but otherwise the similarities are close: there is the same profile with slightly parted lips, the same headcloth with the same striped pattern on it, and the same bright lighting from our left if we allow for the turn of her head.

It is the dramatic lighting, with maximum contrast in the folds of drapery and in the face too, not of Mary in the picture (now in shadow) but of Martha, that most accosts me. I notice as well the jugular vein in the neck of Christ. The wash is applied quickly but with complete assurance. The shadowed area of the face is conveyed in a manner that looks forward to the shadowed halves of the two heads in Washington, the Girl with a Red Hat and the Girl with a Flute.

Girl with a Red Hat (left) and Girl with a Flute (right) (National Gallery Washington)

The strange wavy border that the bright light creates on her cheek, from the near edge of her eye down to her chin is typical of Vermeer’s observation of light, how it produces form, without line, in the most surprising ways. In this respect the Leipzig drawing seems more advanced and prophetic of his future powers than the painting.

The Leipzig drawing, as we have seen, is scarcely a drawing in the linear sense at all, but at Besançon there is a sketch of a more conventional kind. In what becomes his favoured graphic medium - black chalk heightened with white on blue paper - it shows a servant holding a shallow circular basket or tray.

Woman with Tray signed ‘De Hoogh’ (De Hooch)

She is probably not a study for Martha, but one can see the folds of her sleeve following the pattern of light and shadow that is distinctive at Edinburgh in the sleeves of all three participants but more particularly on Christ’s outstretched arm. Her face has the signature oval shape and high-arched brows.

Portrait of a Lady (Royal Collection Windsor)

A third drawing may still be quite early but marks a change to something less loose, less generic, much more personal. This is in the Royal Collection at Windsor, a ‘Portrait of a Lady, Anonymous, Flemish school 91/2 x 7in, black chalk on white paper with red chalk for the flesh and the necklace of pearls’. The cataloguist comments that it is the ‘work of a follower of Rubens lacking peculiar characteristics’. If we stop thinking about Rubens, perhaps its characteristics will start to seem more peculiar, and peculiar, I suggest, to Vermeer. It is likely to be later in date than the Edinburgh picture, but the similarity of facial features if we compare the profile of this middle-aged woman with that of Christ is, for me, compelling.

Detail of Christ at the House of Mary and Martha (left) and Portrait of a Lady (right)

It cannot be proven but my hunch is that this tender portrait is of Catarina Bolnes, Vermeer’s wife, bearer of their many children, and also likely model for the painting at Amsterdam of the pregnant Woman in Blue reading a Letter.

Woman in Blue and detail of face (Rijksmuseum)

Placing her tête-a-tête with Christ and putting aside the double chin so truthfully recorded, notice the mouth, the cupid’s bow upper lip and projecting lower, the depth of the upper eyelid, and the straight nose that nevertheless marks where the bone ends and softness begins. As for ribbons and pearls, they are fashion accessories worn by women in the paintings of other Dutch artists, so their presence in this drawing can only be corroborative evidence; still, we know from later paintings by Vermeer how much he liked his family members to sit or stand for him wearing these adornments, particularly pearls because they represented drops of light.

Whether or not I am right about Catarina, this sensitive, fairly rapid sketch does demonstrate that Vermeer needed to make drawings of his models. The camera oscura was invaluable for helping to accurately determine how furniture and figures are disposed within a chosen perspective, but that tool does not solve everything and I always thought it probable that for the faces at least he would have made some preliminary studies in chalk or oil paint on paper, even if no such drawings survived. Fortunately, as already suggested, a few have, and this is a particularly beautiful example.

Portrait of a Young Man - Anonymous

At Rennes in France there is another close-up drawing, of a youngish man's face, his eyes directed down to our left as we look up. This is texturally very similar to the Windsor drawing, but it more particularly demonstrates three features found in the paintings. One is the drawing of the eyes, the almond shape of the eye itself, the broad strap of upper lid, and the elevated brow. This is famously clear in the Girl with a Pearl Earring at the Mauritshuis, but also in the Kenwood Girl with a Guitar, the Wrightsman Study of a Young Woman (Metropolitan Museum NY) and the two close-ups at Washington, Girl with a Red Hat and Girl with a Flute.

Details clockwise from top left: Girl with a Pearl Earring, Study of a Young Woman, Girl with a Guitar, Portrait of a Young Man, Girl with a Red Hat, Girl with a Flute

A second feature is the lips being parted, as in several of the works just cited. A third is the generous oval or elliptical shape of the face as a whole, which is the result of underplaying the chin and cheekbones.

Studienkopf - Study of a Boy’s Head, attributed to Vermeer

‘Oil paint on paper’ and the above remarks about oval faces are a cue to insert here a small study of a face in that medium that is in the Berlin Printroom. This has long been attributed to Vermeer, not by all but by many scholars from 1907 onwards. It bears all the signs of being by his hand and, besides being a fine and precious thing in itself, is a helpful link to other things. Notice, again, the shape of face that is different from what we find in other artists’ work, the mouth with its wavy upper and sensuous lower lip, a certain relationship and distance between eyebrow and eye, and of course the light that shapes everything. Whether this is an abandoned self-portrait no one can say for sure, but it could be. If one looks hard at oneself in a mirror, the eyes do narrow and squint a little, producing the fixed ‘tunnel’ gaze that this face returns to us so straightly and directly while giving, it must be said, nothing away (but what else would one expect of Vermeer?).

Singender Jüngling - no attribution

From Berlin to Vienna now, and from oil on paper to oil on oak: a small panel in the Kunsthistorisches Museum. This is of a young man singing (Singender Jüngling). The piece of paper he is holding does seem to be a sheet of music and as he is turned towards us with his mouth open he is probably singing, not talking to us about a letter. In any case what matters is that a living moment is caught in a turn of attention with a turn of the head, and thereby temporally and pictorially stopped for ever, as happens over and over in Vermeer. Is this picture by Vermeer? I offer it for consideration. If it is, it is not classic mature Vermeer, nor on the other hand is it very early. I would place it close to the Boston Concert (now sadly missing), the Frick ‘Girl Interrupted At Her Music’, the Metropolitan’s Servant Asleep. It is smaller than any of them, only 91/4 x 71/4 inches, the size, roughly, of the Louvre Lace Maker or the two Washington Girls.

The Concert (stolen)

Girl Interrupted at her Music (Frick)

Servant Asleep at a Table (Metropolitan Museum)

At this point the Berlin oil study on paper provides a helpful comparison: for the shape of the face and of the eyes, the form of the lips (albeit closed in Berlin) and for the lighting if one imagines the face at Vienna upright, not tilted, and facing us straight on.

Detail of Singender Jüngling (left) and Studienkopf (right)

As for the palette the wine-dark brown mantle over the Singing Boy’s right arm reminds us of the colours in the dress of the Sleeping Servant and of the companion of Diana who sponges her foot.

Details of Servant Asleep (top) Singender Jüngling (btm left) and Diana’s servant (btm right)

From surviving images of the Boston Concert, we can not be certain but it seems likely that boy's orange ‘beret’ may be comparable with the chairback of that missing artwork.

Orange beret from Singender Jüngling (left) Chair-back from The Concert (right)

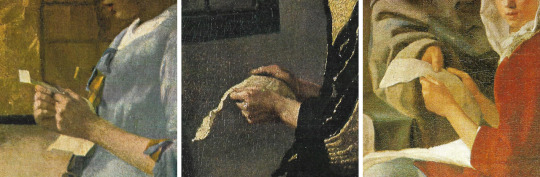

Lighting here is from a source to our left, but Vermeer – if it is he - is not yet committed fully to daylight; the boy is lit within an ambient darkness, much as in a Caravaggio or any number of portraits. The other thing to notice is the way the boy is holding the paper with both hands. One might think that numerous Dutch pictures would show hands in a similar position, but it does not appear that this is so; it is, however, a gesture that recurs in Vermeer, in the Lady in Blue at Amsterdam, the Girl Interrupted at he Music in the Frick, in the Dresden Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window and, we shall see, in another putative Vermeer.

Details from Singender Jüngling (top), Woman in Blue (left), Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window (centre) and Girl Interrupted at her Music (right)

With the Vienna Singing Youth we are, as noted, not out of dark and into sunlight; we are by no visible window and the light has no sparkle. We are in an enclosed world like that of the tavern or the brothel, the venue of the Procuress at Dresden where what light there is, golden and silent amid the muted voices, seems to move surreptitiously, illuminating part of a collar, a bit of wall, a patch of rug before landing in a blaze on a yellow jacket, a scarlet jerkin, a binary echoed in the carpet.

Here is another large early work, disconcertingly different from what precedes and what follows it. The oil medium is drier here and carefully applied with no broad-brush bravura, no squiggles of highlight. Where in the future it is light that will seem liquid, poured into a room as into a tank, here it is shadow that spreads downward, drowning much of the left side of the picture, all but hiding faces, turning the folds of the carpet into dark ravines, and generally claiming the territory. Here is an artist revealing himself, for now, to be potentially as great a poet of shadow as he will be of light; one is readily reminded of Caravaggio’s Calling of Matthew in Rome.

Detail from The Procuress

If we are to find anything to accompany the Procuress in this possibly short-lived stage in Vermeer's development, it must exhibit that dry handling of paint that we see in the depiction of the woman and her client. Again what I offer is a suggestion appended to a sad admission in this case that I have no idea where the picture is. It is a portrait known to me only as an old photo placed among other portraits that have been attributed at some time or another to Velasquez. It is at any rate not by him. It once belonged to a Mr A. W. Leatham.

Portrait - attribution and whereabouts unknown

Here we clearly see, even in a photo, the dryness; but what lends credence to a Vermeer attribution is the face when one compares it with that of the Berlin oil study: within the same generous oval are the same eyebrows, nose and lips; the eyes in the Leatham picture are much more open but otherwise compatible. If this were to be Vermeer's it would be our only independent painted portrait - of whom we may never know.

Maidservant Warming Her Feet - attributed to Vermeer

In the volume referred to at the top of this essay, the 1958 Phaidon Vermeer by Ludwig Goldscheider, there is one drawing included among the main body of plates, a drawing therefore that Goldscheider clearly thought was definitely by Vermeer. It had been published once before, by H Leporini in 1925, but Goldscheider helpfully reproduces it in its actual size. He calls it Maidservant warming her Feet; the original is in the museum at Weimar. The monochrome reproduction gives one a good idea of the soft graininess of the black chalk finely hatched in strokes that run at right angles to the pose of the seated servant. What cannot be seen are the touches of red chalk added to neck and forearm (much as in the Windsor drawing) or the white heightening that in a photo looks deceptively like the white of the paper though the paper in reality is blue.

Why is this beautiful drawing omitted from subsequent books on Vermeer? Could it be that scholars are sceptical on account of the artist’s monogram V M drawn on the side on the footwarmer? One can agree that this is unusual, but that by itself should not be ground for exclusion; genius can be allowed some eccentricity, and anyway it is not too difficult to imagine that this very finished and presentable drawing was in fact presented to someone, possibly the model for it, and that the monogram was added as a mark of the special occasion or as a token of gratitude or to pay a debt. Nobody suggests that it is an outright fake from a later century, so it has to be of Vermeer's time and I question whether any contemporary could produce a drawing of this quality and of this kind - a drawing where form is defined so consistently by light. This is Vermeer's photographic vision, as it would be Seurat’s in a later age.

The Love Letter - Vermeer’s use of light is comparable to Maidservant Warming Her Feet

The sitter, besides: is surely the family's stalwart servant, Tanneke, the same who pours milk and delivers a letter (in two paintings) and maybe holds a jug as she opens a window.

Details from The Love Letter and Milkmaid for which Vermeer used his maid Tanneke as a model

The date of the drawing is anyone's guess, but it clearly belongs in the period of the great cameral pictures. Another drawing, of unknown whereabouts and less remarkable is of similar facture and shows a servant asleep.

Drawing of a Servant Asleep - unknown

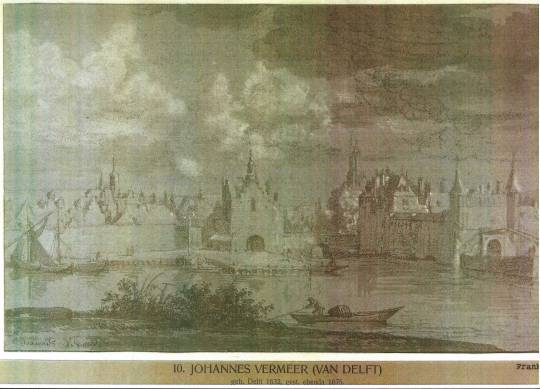

View of Delft by Moonlight - attributed to Vermeer

Scepticism regarding the Weimar drawing seems to have led to doubting generally that any extant drawing is by Vermeer. This is a pity because there is much to be learned from his draughtsmanship. Take this drawing at Frankfurt, a supposed copy of the famous View of Delft from across the canal to the south of the town.

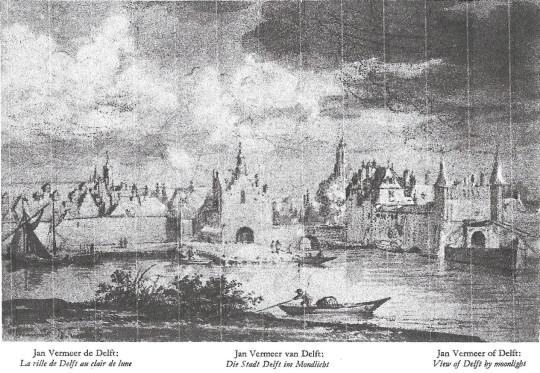

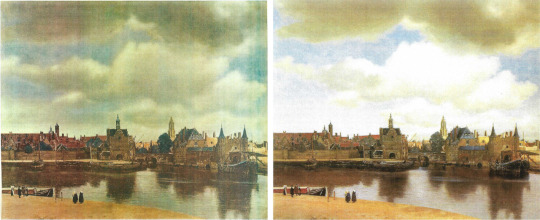

The Original ‘View of Delft’ by Vermeer

Why would a copyist take such liberties with what he is copying from? Why alter the arrangements of the buildings, omit barges, totally change the sky and foreground, remove figures and substitute fishermen in boats? He would be a remarkably inventive copyist who did all that! How much more likely that this is a drawing Vermeer made in situ on a day when there was a busy sky with rain-threatening cloud but with sun behind him that lit the south-facing walls, towers and spires of the town. The painting in the Mauritshuis, like a large ‘Academy’ Constable, is the outcome of onsite visits and studies all of which contributed to his decision-making, but none of which was exclusively determining.

It is very believable that a painter with Vermeer's temperament, seeking always a calm resolution, would not in the end choose a hectic cloudscape, would want to clear the foreground of weeds and bushes, would reject as picturesque a man in a boat who distracts attention from the town across the water, and would decide that the town could not cohere if too many surfaces were lit at the same time across the whole piece. Instead, as we can see in his final consummation, he creates a series of long horizontals from the left, lowers the red- tiled roofline, extends the town wall and the quay, and emphasises all of this with a long placid reflection in the water.

The gap in the reflections comes where the two southern gates of the town connect at the bridge, and that is where he chooses to have the sunlight begin to illumine, not the immediate edge of the town but the buildings beyond and within it; this illumination then continues, ducking and weaving, to the limit of the picture on our right. It can therefore be said to be an outdoor view with an interior, of the town, lit from the right, as only the Lacemaker is among his indoor pictures.

Something curious about the painting vis-a-vis the drawing is the effect created by clearing the foreground of everything except very small figures that lead our eye from a point directly under the reflected left tower of the Rotterdam Gate, across the deserted sandy back to the two women talking, and thence to the group waiting for the ferry at the far left. Vermeer has radically revised in a way that manages to make the town as a whole seem nearer than the foreground figures but as calm and reflective as any of his single figures in a room. At the same time he has concentrated the light in the right half of the picture and given it a warmth to match the pale ochreous emptiness of the foreground that starts from the left, dies towards the right.

Old reproductions of this extraordinary painting show that the cloudscape was perhaps once much more modelled and interesting than it now is. As too often happens, there has been a flattening, a loss of density and volume in clouds that Vermeer knew to have both.

Vermeer’s painting before (left) and after (right) cleaning

If the drawing is original, then it tells us that Vermeer was no different from Ruysdael, Jan van der Cappelle or any of his country's great skyscapists in his understanding that clouds have a superstructure and an undercarriage and as such constitute a sort of moving architecture as they build, dissolve, and build again - a match for earthly buildings shaped by light.

Painting of Maid and Child - attribution and location unknown

The same lesson may be learned from the last item I can offer which, like the Leatham portrait, I know only from a photograph. I do not know its whereabouts or even whether it exists. Coming across the photo lying among unattributed Dutch paintings was nevertheless a memorable moment because I connected the image at once with Vermeer, specifically with his family’s servant, Tanneke, she of The Milkmaid, sitting in her place in the kitchen with a letter held between her hands - in that now familiar position - as she turns aside to attend to a child with a bowl. It seemed clear that the original, of which this may be the only record, was unfinished, abandoned by the artist for whatever reason.

If the original was indeed by Vermeer, then it would be unique among his known works in being a composition with a child in it. Why are there no children in Vermeer's paintings? Did he exclude them because they were too excitable, would never stay still? Did he exclude the elderly because they reminded him of the nearness of death, the fate of too many children of his time, including some of his own? In this case a child does get included, but how securely? Did the artist have doubts? If he took the child out, it would leave the servant looking down to our right for no obvious reason. Her pose is towards our left but her attention is to our right. If the child stays, the chiasm demands something - a small window - in the upper left corner.

Such is the rationale of the image as a composition, but the photo also suggested something about the original’s texture and lighting, factors which go together. What I particularly noticed and was excited by were incipient signs of those lovely beads of light so uniquely characteristic of Vermeer's art.

Details of painting techniques in The Milkmaid (left) and The Glass of Wine (centre) which could be compared with the portrait of Maid and Child

I had supposed that they were last touches, yet the photo appears to make them part of the earlier planning of a picture, prefigured elements in his vision of a scene. If the original ever turned up, we could be satisfied about these technical mysteries.

For myself, I am not sure that I want or need to know how Vermeer painted his pictures; I am reasonably content to marvel at the mysteries and credit them to genius. However, in view of the damage, as I see it, done by conservators to some of the Vermeers that we have in our museums the above old photo from 1947, of a lost picture that passed through the hands of a dealer called Katz, is valuable evidence that from the start of a painting Vermeer knew that what he wanted to record was light, and that light falls in a logical way which creates, according to the time of day, profound areas of shadow that can abut the light with little or no gradation.

Above are two photos using natural light and shadow (left and right) Detail from Lady Writing a Letter with her Maid (centre)

This is most true on a sunny day in the morning, less true by early afternoon. The contrast, clearly visible in the photo, between the lit and shadowed side of a sleeve is extreme. We all know this because we all live in the age of photography, the age that began just before Vermeer started to be rediscovered. Unfortunately for his paintings - and certainly not only his - we also inherit the preoccupations of the twentieth century which to a large extent revolved around the picture plane and its flatness. Combine flatness with iconography, another leading concern, and you get a visual sensibility that finds the pattern on a carpet more important to clarify than the logic of the light which would keep it dark. Here are two photos to illustrate (in the original sense of the word) the contrast that must be respected.

I am not a conservator. Even the thought of surgical intervention in the surface of a Vermeer makes me nervous; but if intervention is ever necessary I think two rules must apply: always respect the logic of the light, and never, if you can help it, reveal the canvas or other support. Vermeer's art is one of illusion, a very poetic and light-sensitive version of trompe l'oeil. Expose the canvas and you destroy the illusion; a wall ceases to ‘be’ a wall and becomes what it mostly is in de Hooch, a bit of brushwork pushed around over a bit of stretched cloth.

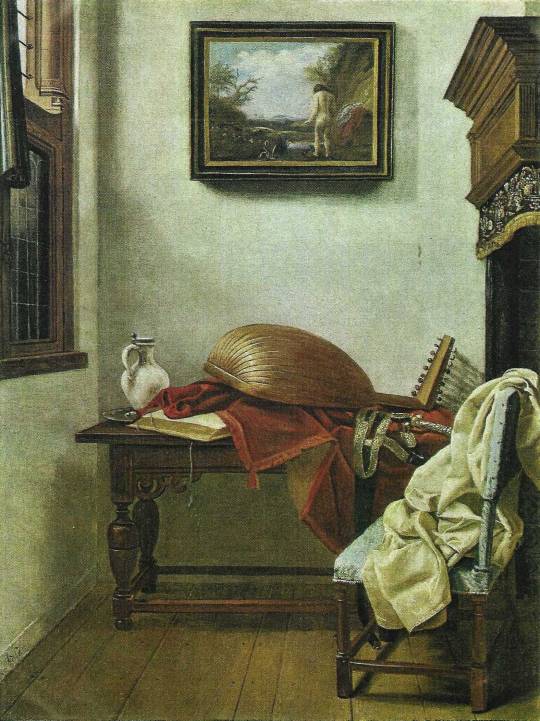

In conclusion I hope it is clear that drawings and even old photos can tell us important things about the essential nature of an artist's vision, the imagination that shapes images, in Vermeer's case through light and light’s dark accomplice. Having opened this essay testifying to my own long admiration for the art of Vermeer, I can best end it on a similar note but in the context of Delft. A painter called Cornelis de Man lived there at the same time as Vermeer and painted some pictures of domestic interiors that are testimony to his own admiration for those of Vermeer, a fellow-townsman and Guild member whom he personally knew.

Still Life with Lute and a Jug - De Man

The picture of Vermeer that is now at Miami (and which was later engraved) is by this artist and very much in the Vermeer manner though crude and inferior by comparison.

Portrait of Vermeer by De Man (left) and engraving thereof (right)

Also by this artist is a far better and more finished picture at Polesden Lacy near Dorking.

The Game of Cards - De Man

It shows a middle-aged man facing a young woman over a table where they are playing cards. A young child to the right who stands hardly higher than the table on which one hand rests looks out of the picture to direct, perhaps, another child's attention to the grown-up’s game. The young woman looks round towards us as one might turn to a camera.

Details from De Man’s Portrait of Vermeer and The Game of Cards

Comparing the face of the man with that of the painter in the Miami picture, I think it very probable that we are looking at Vermeer himself relaxing opposite one of his daughters, with another of his many children beside him. The picture can stand in any case as a pleasant memorial to that genius of a ‘family man’, celebrant of town, home, kin and friends, who was happy to include those closest to him in what are still, despite the cleanings, some of the greatest of all representational paintings.

Julian Pritchard

March 2017

#vermeer#art history#dutch painter#flemish school#art theory#painting techniques#stolen art#frick museum#metropolitan museum of art#kenwood house#cornelis de man#girl with a pearl earring#connoisseurship

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Johannes Vermeer ; The Girl with a Pearl Earring

Sometimes it is called "Mona Lisa of the North" or "Dutch Mona Lisa".

1665. 46.5 x 40 cm. Royal Picture Gallery Mauritshuis, Den Haag.

#art#famous artists paintings#famous art pieces#artwork#famous oil painting#famous paintings#vermeer

99 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Carel Fabritius, The Goldfinch, 1654 , Oil on panel Royal Picture Gallery, Mauritshuis, The Hague

17 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Summer Flowers (Flowers in a Metal Vase in a Niche), Abraham Mignon, ca. 1670

#art#art history#Abraham Mignon#still life#floral painting#flowers#Dutch Golden Age#Baroque#Baroque art#Dutch Baroque#Dutch art#German-Dutch art#17th century art#Mauritshuis#Royal Picture Gallery Mauritshuis

1K notes

·

View notes

Video

instagram

Girl with a Pearl Earring, c. 1665 By Johannes Vermeer. From the series:Stolen from the Royal Picture Gallery Mauritshuis Dry paint on Sheetrock, 48X48. 2014 #StolenfromtheRoyalPictureGalleryMauritshuis #Mauritshuis #JohannesVermeer #GirlwithaPearlEarring #pavelacosta #collage #chelsea #ptotograthy #manhattan #fineart #art #artwall #instalation #bernicesteinbaum #artday #contemporaryart #alternative #interiordesign #artist #curator #contemporarypainting #artwalk #caribbeanartist #drywallartist https://www.instagram.com/p/Bsm0iKMl9fx/?utm_source=ig_tumblr_share&igshid=uh686flfapj8

#stolenfromtheroyalpicturegallerymauritshuis#mauritshuis#johannesvermeer#girlwithapearlearring#pavelacosta#collage#chelsea#ptotograthy#manhattan#fineart#art#artwall#instalation#bernicesteinbaum#artday#contemporaryart#alternative#interiordesign#artist#curator#contemporarypainting#artwalk#caribbeanartist#drywallartist

1 note

·

View note