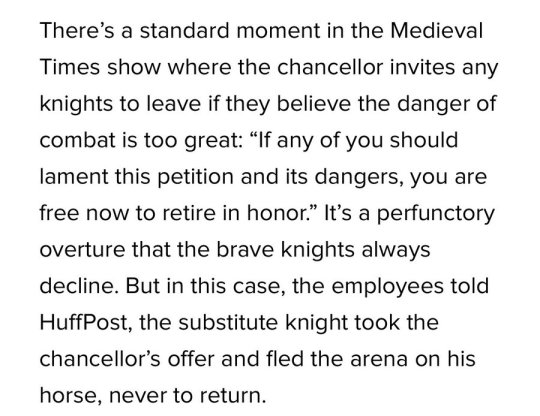

#scabs retire in (dis)honor

Text

MEDIEVAL TIMES STRIKE!!!

440 notes

·

View notes

Text

part 9

previously: one, two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight

Laurent was injured. Damen had known there would be some reason that he had not come at Charcy and instead set himself up in a confection of a tent outside Fortaine. So Damen had looked closely at how Laurent stood, how he held himself, where the tension in his body was, and compared it to his knowledge of Laurent’s body and his usual careful posture, and then grasped his shoulder.

Damen was correct, but he felt little satisfaction at the accuracy of his guess in the face of Laurent’s cruelty.

“The man who stood by me, who gave me good counsel, who never lied to me, he was an illusion,” said Laurent.

“I never lied to you,” said Damen.

“That man never existed,” said Laurent. “I don’t know who you are.”

“We are the same,” Damen said. “I am him.”

“Come here, then,” said Laurent. He beckoned for Damen to step closer. He meant to bite Damen, Damen knew. Damen could see the hunger in Laurent’s eyes. That made sense. The still-bleeding injury in his shoulder would have lost him a lot of blood, and he might have been injured in other ways in the same event, whatever it had been. He would want blood for strength, the way he had after he’d been beaten by the Vaskians, and the taste of it had restored him.

Damen thought of Nikandros and the Akielons outside, of the men who had died fighting at Charcy waiting for reinforcements that did not arrive.

“No,” he said. “You’re right. I am the king; you will parlay with me like a king. Tell me why you have called me here.”

Nikandros was warning Damen off of Laurent from the first day that they met, even before he found out.

If Damen had continued to let the slaves dress him, it would probably never have happened. As he adopted Akielon fashions rather than the Veretian ones he had been wearing, he could have simply continued pinning a cloak at his neck and wearing bracers on his wrists and no one would have noticed anything except the king setting a new trend for short cloaks and taking an uncharacteristic interest in archery.

But he had rejected slaves to dress him, and demanding a squire instead, and squires were not trained in the manner of slaves.

Nikandros came to his tent and told everyone else to leave.

Damen stood, wondering what the trouble was that required a confidential report.

Nikandros came and stood next to him, and then tugged at the cloak Damen was wearing--which was closed with his pin, the pin Nikandros had risked treason to take--and let the fabric drop to the floor.

“Who did this to you?” said Nikandros.

“I see my squire cannot be trusted,” said Damen, mildly.

“Who?” said Nikandros.

“You know who did it,” said Damen.

“I’ll kill him,” said Nikandros.

“You will not,” said Damen. “I forbid it.”

“He’s bewitched you,” said Nikandros. “He has your mind caught in some kind of trap.”

“That is a myth,” said Damen, “like transforming into a bat.”

Nikandros gestured at the scars on Damen’s neck. “I thought this was all a myth.” He ran a hand through his own hair. “I know what it would have taken to subdue you--to imagine what he must have done, to do this--”

“Don’t think of it.”

“Take off all of your clothes,” Nikandros told Damen.

“Are you giving your king an order?” said Damen.

Nikandros said nothing but stared at Damen evenly.

“You also,” said Damen, indulging his childhood friend, and the two of them stripped in silence. Damen bore Nikandros’s intrusive inspection. He was reminded of Paschal, and the taste of broth. Damen did not pay much attention to the scarring himself, but he saw it again now through his friend’s eyes. His wrists were not so bad, mostly pairs of dots that were not immediately obvious as to their source. Nikandros understood, of course, but if Damen were not not wear a bracer they did not immediately draw attention among all of his other scars. His neck was worse; there was a line of obvious bites along his shoulder from the baths, and the more recent injury from the Vaskian camp was still a series of scabs. Damen had reopened it in the fighting at Charcy, and it had bled again, and was now healing a second time.

After Nikandros had made a through check of Damen’s body, Damen spoke. “I am fine.”

Nikandros turned large eyes on Damen. “Are you certain I cannot fight him.”

“Yes,” said Damen. “Also he is surprisingly good; you would need to be prepared.”

“It pains me,” said Nikandros. “We ride along the border and the people cheer at his banner, but to know that the man they are cheering for has done this to you--and that you have not struck back at him but are allying with him and giving generous gifts--”

“I struck first.” said Damen.

Nikandros stopped.

“We struck first,” said Damen. “I killed his brother and I set into motion things that are playing out to this day.”

“That was honorable,” said Nikandros. “You challenged him on the field, you didn’t trick him into--” Nikandros did not even seem willing to put it into words.

Damen gestured at himself. “None of this would have happened if I hadn’t killed Auguste.”

Nikandros seemed to give up, and he collapsed down onto one of the piles of cushions spread out in the tent. There were refreshments set out next to the cushions, and Nikandros drank from one of the goblets.

Damen sat down next to him more slowly.

“Thank you, old friend, for caring about me,” said Damen.

Nikandros took another drink from the goblet. “If he tries to bite me, I’m killing him.”

Damen laughed, startled, both by the notion that Laurent would try to bite anyone else and Nikandros’s wry humor. “All right, permitted,” said Damen, smiling, and he reached out his hand for Nikandros to hand him the goblet.

Nikandros’s joke started Damen thinking about Laurent and other people. Paschal had told him, back in their first days on the road, that the Prince’s habits were austere. Laurent had said in the inn that it wasn’t necessary for him to drink. Did that mean that he abstained, until that day when Damen was presented in front of him in chains?

Damen could tell from the way Laurent held himself on his horse that his shoulder wound was healing naturally, so presumably he wasn’t, now, either. Though when they arrived at Marlas and the slave master Kolnas presented Laurent with his best and Laurent touched Isander’s hair, Damen wondered. Isander followed Laurent obediently off to his rooms and to the bath. Damen thought of it.

He imagined Laurent and Isander first in the blue and green tiled baths of the palace at Arles, and then he corrected himself, because he knew the baths at Marlas. He had bathed there before when visiting Nikandros. So he moved them from the setting of his own memories of bathing Laurent to the real baths at Marlas, which were filled with white marble. There was water that flowed over a wall as an artificial waterfall, Damen remembered, and then a relaxing pool with benches for after washing. They would be in the pool, Damen supposed. Blood might drip down from Laurent’s mouth and fall in tiny red drops on the marble, Damen thought.

Isander might cry out, when Laurent’s teeth cut him, because he was a slave and not accustomed to such harsh treatment. Or perhaps he would stop his voice with the perfect obedience he was trained to, and merely tremble, waiting.

Then they would retire from the baths, and they might be right through the dividing door of the connecting room royalty were given at Marlas. Damen fought the urge to press his ear to the door ridiculously.

After Laurent drank with Makedon, Damen helped him down the corridor to the Queen’s chambers that he had been allotted.

Laurent was talkative, drunk, it was amusing until Damen thought about Laurent’s likely temper the following morning.

“I miss you,” said Laurent.

Damen snorted. “Yes, I suppose you wish you could have healed your shoulder much faster. Or is it that you think you could have beaten me in the ring if you’d only been stronger?”

“No,” said Laurent. “I don’t even care about that. I miss our conversations.”

“You’re drunk,” said Damen, half to Laurent and half to himself. “You don’t know what you’re saying.”

“You don't like me like this?” said Laurent, lying where Damen had poured him onto the bed.

“You are not yourself.”

“Maybe it’s better. Defenseless. Free. Less dangerous.”

Damen brushed some of Laurent’s hair away from his face. “I like danger,” he said. “Sleep it off.”

part 10

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

Emmett Till’s Murder, and How America Remembers Its Darkest Moments

Emmett Till’s Murder, and How America Remembers Its Darkest Moments

https://ift.tt/2SeMIif

We're using augmented reality, a new approach to digital storytelling. Read about how to use it on your phone or tablet here. If you want to skip it for now, you can view an alternate immersive experience instead.

MONEY, Miss. — Along the edge of Money Road, across from the railroad tracks, an old grocery store rots.

In August 1955, a 14-year-old black boy visiting from Chicago walked in to buy candy. After being accused of whistling at the white woman behind the counter, he was later kidnapped, tortured, lynched and dumped in the Tallahatchie River.

The murder of Emmett Till is remembered as one of the most hideous hate crimes of the 20th century, a brutal episode in American history that helped kindle the civil rights movement. And the place where it all began, Bryant’s Grocery & Meat Market, is still standing. Barely.

Today, the store is crumbling, roofless and covered in vines. On several occasions, preservationists, politicians and business leaders — even the State of Mississippi — have tried to save its remaining four walls. But no consensus has been reached.

Some residents in the area have looked on the store as a stain on the community that should be razed and forgotten. Others have said it should be restored as a tribute to Emmett and a reminder of the hate that took his life.

As the debate has played out over the decades, the store has continued to deteriorate and collapse, even amid frequent cultural and racial reckonings across the nation on the fate of Confederate monuments. At stake in Money and other communities across the country is the question of how Americans choose to acknowledge the country’s past.

“It’s part of this bigger story, part of a history that we can learn from,” said the Rev. Wheeler Parker, 79, a pastor in suburban Chicago and a cousin of Emmett’s who went with him to Bryant’s Grocery that day. “The store should be one of the places we share Emmett’s story.”

(The Justice Department quietly reopened the Emmett Till case last year after Carolyn Bryant Donham, the white shopkeeper, recanted parts of her story.)

In and around the Delta, the memory of Emmett’s murder lingers.

The cotton gin from which the 75-pound fan that was tethered to his neck with barbed wire was stolen is now a small museum. There are informal tours of the abandoned bridge where his body was likely tossed into the river. The barn where he was brutally beaten is unmarked, but its owner allows the occasional visitor.

Emmett Till with his mother, Mamie Till Mobley, circa 1950. Everett Collection, via Alamy

And, on a larger stage, his story is the subject of upcoming feature films and books.

But not everybody sees the memorials the same way. Several historical markers put up to commemorate Emmett have repeatedly been vandalized, shot down and replaced.

To nurture racial reconciliation in the area, the Emmett Till Memorial Commission was founded in 2006. It restored the courtroom in Sumner where Emmett’s killers — Roy Bryant, the owner of the store in the 1950s, and his half brother, J.W. Milam — were acquitted. Outside, a marker commemorating Emmett stands steps from a monument honoring Confederate soldiers.

Ray Tribble, who sat on the jury of all-white men who acquitted Mr. Bryant and Mr. Milam, purchased the building that was once Bryant’s Grocery in the 1980s. He died in 1998. The store has been in the Tribble family ever since.

The family has all but refused to restore or sell the property. And it continues to wither away.

Drag image to explore

The remnants of Bryant’s Grocery & Meat Market, in Money, Miss.

‘Tear Off the Scab’

Willie Williams and Donna Spell grew up about eight miles from each other in the Delta. They are 10 years apart in age. He learned about Emmett Till as a child. She learned about him as an adult. Mr. Williams is black. Ms. Spell is white.

Mr. Williams said his parents told him about Emmett’s story “as a way of being careful.” Ms. Spell said Emmett’s horrific death was not a story “my parents would have told their children.”

The two first met at a church event. Today, they both sit on the Emmett Till Memorial Commission, where they have since become friends.

“I did a lot of listening. And what I heard was a lot of pain,” said Ms. Spell, a longtime English teacher. “To move forward we’ve got to tell the story. We’ve got to tear off the scab and keep telling it.”

In 2006, the Emmett Till Memorial Highway was dedicated along a 32-mile stretch of U.S. 49 East. A year later, the commission presented an official apology to the Till family in the courthouse where the killers were acquitted.

Drag image to explore

The Emmett Till Memorial Commission restored the courtroom in Sumner where Emmett’s killers were acquitted. The courtroom was segregated during the trial in 1955.

“Our community had been running from this since 1955,” said Patrick Weems, co-founder of the Emmett Till Interpretive Center, a museum across from the courthouse that was started by the group.

The commission has since placed 11 historical markers at sites related to Emmett’s murder. One of them sits on a lonely dirt road next to rows and rows of cotton fields near Glendora, Miss. It’s a purple sign marking the nearby riverbank where Emmett’s body was recovered.

The sign has had to be replaced three times because of bullet holes and vandalism. Other civil rights markers in Mississippi have also been targeted — two years ago, vandals scraped the words and text off the Bryant’s Grocery marker, and “KKK” was once scrawled across the highway sign.

Several historical markers have been erected to honor Emmett. One of them, a purple sign marking the nearby riverbank where his body was recovered, has been repeatedly vandalized.

On a recent afternoon, one of the commission’s damaged signs rested on the floor of the museum. Mr. Weems leaned over it as he ran his fingers across the jagged holes.

“It’s been a struggle to keep those signs up,“ Mr. Weems said, “but we think it’s part of the front line of this tug of war between memory and how we negotiate our past and future.”

[For more coverage of race, sign up here to have our Race/Related newsletter delivered weekly to your inbox.]

Drag image to explore

The riverbank where Emmett’s body was recovered.

Confronting History

Susan Glisson has worked with a half-dozen Mississippi towns on racial healing, including in Sumner with the Emmett Till Memorial Commission. After she retired as director of the University of Mississippi’s William Winter Institute for Racial Reconciliation, she founded Sustainable Equity, a consulting firm focused on facilitating racial dialogue at universities, police departments, corporations and municipalities.

“When it works, we are able to get past the perspective of ‘I didn’t do it, I don’t know anybody that did it,’ and find the ways to honor the victims,” Ms. Glisson said.

When it doesn’t work, she went on, the resistance is stark: communities fracture, landmarks are neglected, significant events are lost or forgotten. These moments of tension and reckoning have buckled across America as small towns confront their racist histories.

In northwest Florida, an all-black town was wiped off the map by racial violence during the Rosewood massacre in 1923. The one house that survived — where black residents hid to escape the slaughter — is now owned by an 85-year-old Japanese widow, Fujiko Scoggins. Her daughter and son-in-law, both real estate agents, are selling the home.

A small heritage group wants to convert it into a Rosewood museum and garden, but hasn’t secured funding. Neighbors warned Ms. Scoggins’s son-in-law not to sell the house to black buyers, presumably to stop any commemoration of the massacre.

The historical marker and road sign have been repeatedly vandalized. “The message is they don’t want Rosewood or the massacre to be remembered,” said Sherry Dupree, founder of the Rosewood Heritage Foundation and a tour guide.

In Monroe, Ga., a racially violent chapter is commemorated annually. Two African-American married couples were murdered by a white mob near the Moore’s Ford Bridge, after a dispute with a farmer in 1946.

Since 2005, a group of actors and activists have gathered each year to re-enact what happened that July night. “The people in town pretty much ignore it now every year,” said Cassandra Greene, who directs the performances. “But it’s important to keep doing it as a reminder of racial injustices.”

Memorials have the power to invite meaningful race conversations, Ms. Glisson added, but the key is addressing stubborn attitudes, stereotypes and assumptions that have been hardened and passed down over generations. The difficulty is getting beyond feelings of recrimination and guilt.

‘Remembering Emmett Till: The Legacy of a Lynching’ in Virtual Reality

‘It’s Been Complicated’

The price of Bryant’s Grocery & Meat Market, according to one Mississippi newspaper, is $4 million, but it’s hard to know more because the family has largely refused to talk publicly about it. Numerous messages and emails sent to the Tribbles for this story went unreturned.

In 2011, the family was awarded a $206,000 state civil rights grant to restore a gas station next to the store. At the time, the project’s architect described the store restoration as the next phase. Since 2015, Mr. Weems has negotiated with family members, to no avail.

There’s talk in town of a replica being built on state property across the street by one of the production companies filming movies about the Emmett Till case. That may be the only solution.

“It’s been complicated working with the family,” Mr. Weems said. “We have had off and on discussions with the Tribbles for about three years and it seems as if every time we get close, they move the goal post.

“And I still don’t know what they want,” he added. “I don’t know if it’s money or they want control of the story that’s told, which has direct legacy implications for their father. I am hopeful that one day they can see a positive legacy by reclaiming the past.”

Today, fewer than 100 people live in Money and most of the property, including the old Bryant’s Grocery store, is owned by the children of Ray Tribble.

Drag image to explore

The barn where Emmett was brutally beaten is unmarked, but the owner allows the occasional visitor.

As early as 2004, local business and civic leaders reached out to the Tribble family in hopes of turning the store into a museum dedicated to Emmett or civil rights, or both, even in its current state of disrepair.

That same year, the roof caved in. Then Hurricane Katrina rumbled through in 2005, destroying much of what remained. Back then, the Tribble family agreed to work to rebuild the store. “We want to restore it,” Mr. Tribble’s son, Harold Ray Jr., told The Clarion Ledger in 2007. “It’s a part of history and it’s about to fall down.”

Nothing has been done. And every day, the store slips closer toward oblivion.

“Here is this ruin that a storm could blow over, and yet it’s still here,” said Dave Tell, an author and professor working on a new book about the Emmett Till case.

“The store is this great analogy to the story of Emmett Till, both long neglected, but both refuse to go away.”

CREDITS

Written by Audra D.S. Burch.

Produced by Veda Shastri.

Drone Video and Photos by Tim Chaffee.

Archival Images: Everett Collection via Alamy, Ed Clark/Time & Life Pictures via Getty Images, Associated Press

Graphics and Design by Nicole Fineman, Jon Huang, and Karthik Patanjali.

Research by Susan C. Beachy

Senior Producer: Maureen Towey

Executive Producers: Lauretta Charlton, Marcelle Hopkins and Graham Roberts

A Grocery, a Barn, a Bridge: Returning to the Scenes of a Hate Crime

Emmett Till’s Murder: What Really Happened That Day in the Store?

In Texas, a Decades-Old Hate Crime, Forgiven but Never Forgotten

Talking to a Man Named Mr. Cotton About Slavery and Confederate Monuments

Veda Shastri contributed reporting, andSusan C. Beachy contributed research.

Advertisement

https://ift.tt/301mY0P

via The New York Times

September 15, 2019 at 06:51PM

0 notes