#selver thele

Photo

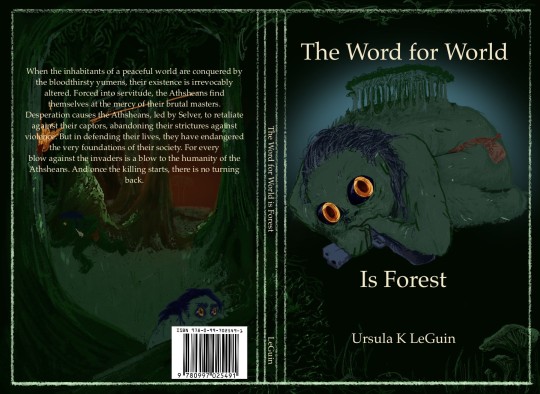

assignment: book cover

I chose The Word For World Is Forest by Ursula K. LeGuin

i may have some details wrong, but this was how I imagined Selver.

description

#consider reading the book about space colonialism where the colonizers lose instead of say the new avat*r movie#ursula k leguin#the word for world is forest#illustration#procreate#selver#selver thele#twfwif

1 note

·

View note

Text

Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Word for World is Forest (1972) is an interesting and compelling book that discusses heavy themes surrounding colonialism, invasion and exploitation. As MacLeod puts it, ‘The Word for World is Forest is a reflection […] on the necessity and cost of resistance’ (2015: 1).

Le Guin wrote this book during the time of the Vietnam War, which is heavily referenced throughout through the character Colonel Dongh, who enables and supports the enslavement of the Ashtheans (Watson 1975: 231). Dongh is a character who, like many other humans (‘yumens’, as the Ashtheans call them), are cruel and oppress the native Ashtheans on New Tahiti. Ashtheans are subjected to heavy colonisation and the abusive effects of it, such as forced labour, rape, and genocide (Debita 2019: 51). Indeed, despite Le Guin using the peace movements she was involved in as her outlet to keep her political views and her writing separate, I believe that Le Guin’s political stance is clear through her use of her characters in the book. (Savi 2021: 536, quoted in Burns 2010).

Through the atrocities that occurred during the Vietnam War, Le Guin states in her Author’s Introduction of The Word for World is Forest that ‘[she] never wrote a story more easily, fluently, surely - and with less pleasure.’ Le Guin was opposed to the idea of atomic bomb testing, and the war in Vietnam in general, and would often feel ‘useless, foolish, and obstinate’ (Le Guin, 1972) because of the higher authority destroying the lands and forests; killing other men in the name of peace. It is through this heavy opposition to this unethical method of achieving such an agenda that she created The Word for World is Forest. Le Guin ‘responds to the dehumanizing nature of war that made possible Viet Nam era atrocities’ (Savi 2021: 536, quoted in Lindlow 2012), and this is certainly evident in how the character Don Davidson treats the “creechies”, which he derogatorily calls the Ashtheans.

Le Guin also mentions in her Author’s Introduction that her unconscious mind created a pure evil character - Davidson - despite her knowing very well that purely evil people do not exist (Le Guin 1972). Unlike Raj Lyubov, a character that studies the Ashtheans and tries to understand their lifestyle and their culture, Davidson fails to understand Ashthean ways of living - during his conversation with Oknanawi in Chapter 1, he states that hitting a creechie is “like hitting a robot for all they feel it”, and they’re “dumb, […] treacherous, and they don’t feel pain.” Furthermore, Lyubov mentions Davidson’s sexual intercourse with a creechie, who was Selver’s wife, Thele. This sexual assault is what lead to her death, and what was the driving force for Selver to attack Davidson in Chapter 1.

However, it is Selver’s character (and the Ashtheans’ dreaming culture as a whole) that led my practical response to this book. As Savi states, ‘Ashtheans are experienced day-dreamers’ (2021: 544), and I created my etchings through the link between the Ashtheans’ connection to their forest and the practice of Buddhism. Looking at Indian, Japanese and Tibetan Buddhist art, I drew upon the beautiful and calming sceneries of mountains, glistening rivers, and lotus flowers blooming in the water. Nature was the key to ‘attain enlightenment’, and was considered the ‘Pure Land’ (Bloom 1972: 117). Buddhism, which is still widely practised, enables people to have a sense of belonging in nature, to be one with the leaves and the sky, and the flowing rivers (Kala 2017: 24). I made a link between Buddhists aiming to reach Nirvana, and the Ashtheans using the concept of dreaming to gain answers from their gods.

My etching consists of a pair of hands holding a bloomed lotus flower, which has a heart-shaped vine growing out of it, adorned with depictions of the various natural imagery we used to live in before our Modern Age. I wanted to represent humankind’s appreciation for nature, and how we should still be one with nature, and hold it in high regard, despite our destroying of trees and natural resources to aid and sustain human life. Reading about the humans’ destroying of New Tahiti to help an already-destroyed Earth in The Word for World is Forest, I felt an overwhelming urge to create a positive and peaceful outcome in response.

However, although I wanted to have a positive outlook on my practical response and the book as a whole, one cannot ignore the negative and depressing ending of the book. Although the Ashtheans were able to obtain their land back from the humans, they have been introduced to murder, despite them being harmless and nonviolent species before. Their old way of life is no more, and the world they used to live in will never be the same again. The strong reference to real life ecological issues is evident here - people’s greed and selfishness have destroyed the planet, both physically and spiritually. People are out of balance between their status as humans and the nature around them (Hurby 2017, quoted Farong 2017). It raises many questions about how humanity stands: will our world ever be the same even if we are able to save our forests and planet? Will we ever be the same if we regain our spiritual connection to our natural environments? For me, I will always ask the question: will Mother Nature ever forgive us for ruining Her planet?

Bibliography

Bloom, A. (1972) ‘Buddhism, Nature and the Environment’, The Eastern Buddhist, 5(1), pp. 117-119.

Brown, K.S. (2003) Tibetan Buddhist Art in Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Available at: https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/tibu/hd_tibu.htm (Accessed 19 December 2023).

Debita, G. (2019) ‘The Otherworlds of the Mind: Loci of Resistance in Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Word for World is Forest and Voices (Book II of the Annals of the Western Shore)’, Cultural Intertexts, 9, pp. 51.

Hurby, D (2017) Taoist monks find new role as environmentalists. China Dialogue. Available at: https://chinadialogue.net/en/nature/9669-taoist-monks-find-new-role-as-environmentalists/ (Accessed 19 December 2023).

Kala, C.P. (2017) ‘Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources through Spirituality’, Applied Ecology and Environmental Sciences, 5(2), pp. 24.

MacLeod, K. (2015) The Word for World is Forest in The Anarchist Library. Available at: https://theanarchistlibrary.org/library/ursula-k-le-guin-the-word-for-world-is-forest-1 (Accessed 5 December 2023).

Savi, M.P. (2021) ‘Looking to Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Word for World is Forest: A Mirror of the American Consciousness’, Extrapolation, 30(1), pp. 536.

Watson, I. (1975) ‘The Forest as Metaphor for Mind: “The Word for World is Forest” and “Vaster Than Empires and More Slow”’, Science Fiction Studies, 2(3), pp. 231-232.

0 notes